This sample Robbery Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Robbery is a violent crime but also a property crime since the motivation is theft. It is a fear-inspiring crime since it typically involves an unprovoked attack by strangers. In the United States, there has been a large decline in robbery rates since the peak in the early 1990s, especially in the largest cities. Some of the pronounced patterns in robbery are just what we would expect if robbers were rational actors seeking a quick score by gaining physical power or control over the victim. Most robberies are committed with lethal weapons and involve two or more perpetrators, usually young males. Gun-wielding robbers are more likely to choose stronger victims and to successfully complete the theft without much resistance. Nonetheless, gun robberies are much more lethal than robberies with knives or clubs. A variety of situational and police-manpower approaches to robbery reduction have been successful.

Introduction

Robbery is a crime of violence motivated by theft. The spectrum of robbery ranges from schoolyard shakedowns for lunch money to bank holdups with losses reaching into the millions of dollars. Property losses from robbery are, however, usually small or nil, and it is the violence that makes robbery such a serious crime.

Robbery is particularly fear inspiring because it usually involves an unprovoked attack by strangers. In that regard it differs from assault, which typically involves an altercation between acquaintances. The public concern about “crime in the streets” is to a large extent a concern about robbery, and that concern may have profound effects on the life of the city, through its influence on choices about where to live, work, shop, and go out to dinner (Cook and Ludwig 2000). James Q. Wilson and Barbara Boland note that “[i]t is mostly fear of robbery that induces many citizens to stay home at night and to avoid the streets, thereby diminishing the sense of community and increasing the freedom with which crimes may be committed on the streets” (Wilson and Boland 1976, p. 183).

This research paper provides a description of trends and patterns in robbery using police statistics and statistics from crime surveys. The focus is on data for the United States, which has the best established of the national crime surveys. The survey data support a fine-grained analysis of the age, sex, race, and number of robbers and victims involved in an incident, as well as the type of weapon and the outcomes of the confrontation with respect to theft and injury. It is helpful to understand these patterns through the lens of the robbers’ instrumental concerns – identifying lucrative “targets,” preempting resistance, and avoiding arrest – although some violence is simply gratuitous.

Robbery prevention efforts include private protection efforts for prime commercial targets (guards, closed-circuit cameras, reduced cash on hand) and directed police patrol against street robbery. Probably more important has been the evolution toward a cashless economy, reducing the robbers’ chances for a quick payoff. Reducing the overall robbery rate is not the only goal – a second public goal is harm reduction. For example, measures to reduce gun use in robbery have the potential to reduce the rate of serious injury and murder.

This research paper consists of four main sections and a conclusion. The first section discusses robbery rate trends in the United States since the 1960s – increasing through 1981, down since 1991, and fluctuating in between – and relative to rates elsewhere. The second section, based on victimization dates combined for the years 2000–2005 to provide sufficiently large numbers to support generalizations, examines the demographics of robber perpetration and victimization and robbery outcomes (property loss, injury, and death). The third discusses robbers’ strategic choices about whom to rob and how, with what weapon, and what differences those choices make. The fourth discusses interventions aimed at preventing robberies.

A number of conclusions are offered:

- Although data comparability issues preclude confident assertions, American robbery rates as shown in official data and victims’ reports appear comparable to those of other developed countries.

- Official and victim data concur in showing a very substantial decline in robbery rates since the early 1990s.

- Most robbers are male (more than 90 % in 2000–2005), young (74 % under 30), and African American (54 %).

- Most robberies do not yield high profits for robbers (only 29 % yielded cash) but nearly half of victims are physically attacked.

- Robberies with guns are less likely to result in victim injuries than are other robberies but are much more likely to result in death.

- A variety of situational and police-manpower approaches to robbery reduction have been successful.

Data And Trends

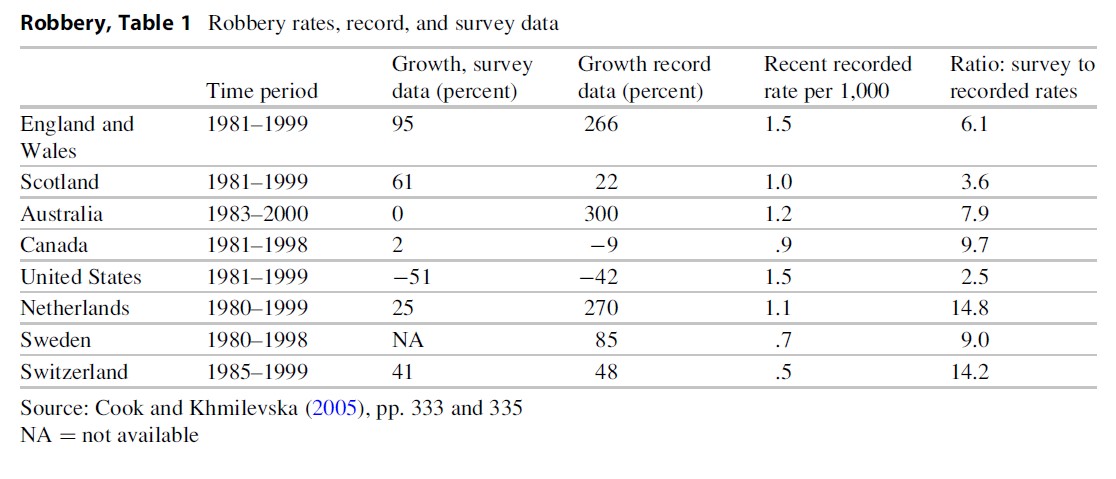

The volume, trend, and patterns of crime can be measured by the use of two sorts of data: victimization surveys and records of crimes known to the authorities. A careful analysis of data for eight high-income nations offers insight into the difficulty in developing reliable measures (Farrington et al. 2004). As shown in Table 1, the recorded rates circa 1999 ranged from 0.5 per 1,000 (for Switzerland) up to 1.5 per 1,000 (for both the United States and England and Wales). But the survey estimates were far higher and suggest a different lineup; for example, while the survey rate for the United States was 2.5 times the recorded rate during the 1980s and 1990s, for the Netherlands the survey rate was nearly 15 times as high as the recorded rate and was a multiple of the US survey rate. Furthermore, in several of these nations, the trends in the survey measure look quite different than the trends in the recorded measure.

Of the various national crime surveys, the United States National Crime Victimization Survey is best established, generating annual estimates since 1973, and also has an important technical advantage over the others. The NCVS interviews the same households every 6 months over seven cycles, encouraging the respondents to use the previous interview as a mental baseline to define the relevant period. That device helps limit an important source of error in survey-respondent reports, namely, the tendency to report important victimization experiences that occurred outside the specified interval (6 months or a year) – a recall problem known as “telescoping.” Other nations do not use this costly procedure and hence may have more telescoping and a positive bias to survey results.

The NCVS helps uncover the “dark figure of crime” that goes unreported to the police. In 2010, for example, the NCVS estimated 568,510 noncommercial robberies, compared to 367,832 robberies of all types tabulated through the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) system which compiles crimes known to the police. Only about 40 % of noncommercial robberies are reported to the police. The NCVS data are also useful in providing the statistical basis for analyzing demographic patterns of violence – both of the victims and of the perpetrators (based on respondents’ reports of their impression of the age, race, sex, and number of assailants). They also provide an empirical basis for characterizing process and outcomes of criminal incidents.

Since the interview subjects are households, commercial robberies and other crimes against businesses are not included. According to 2010 UCR data, about 40 % of robberies reported to the police occur in businesses. The true percentage may be lower if businesses are more likely to report victimization than are individuals.

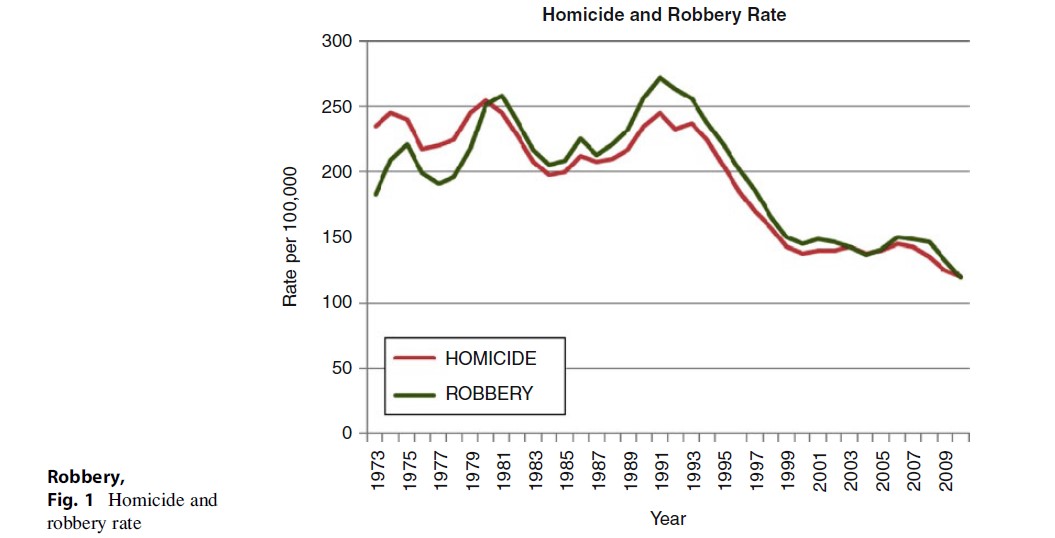

For the period since 1973, the NCVS data indicate that victimization rates for personal robbery were cyclical with peaks in 1974, 1981, and 1994; since 1994 there has been a sustained drop from 6.3 per 1,000 to just 2.2 per 1,000 in 2010. UCR robbery rates have roughly the same peaks and valleys as the NCVS rates, and they too show a strong downward trend during the 1990s (Blumstein et al. 1991). As documented by Alfred Blumstein (2000) and shown in Fig. 1, UCR robbery rates have moved up and down for the last several decades in synch with murder rates which are the most reliably measured of all crime rates. (Note that the homicide rate has been scaled up by a factor of 25 in this diagram so that it is on a similar scale as the robbery rate.) It appears, then, that the UCR robbery trends are reliable.

The extraordinary reduction in robbery and other violent crime during the 1990s remains something of a mystery – no expert predicted this decline – but some credit surely goes to increases in the size of police forces and stringent sentencing policies that greatly increased the prison population (Blumstein and Wallman 2000; Cook and Laub 2002; Levitt 2004; Blumstein and Wallman 2006; Zimring 2007; Zimring 2012). The crack epidemic that began in the mid-1980s contributed to the surge and later decline of robbery: by one account, crack users turned to robbery rather than other forms of theft (such as burglary) because it was the quickest method of obtaining cash (Baumer et al. 1998). Other plausible (but contested) explanations for the drop in robbery and other violence include the sustained economic expansion of that period, innovations in policing, the delayed effects of the legalization of abortion, and the removal of lead from gasoline.

The 1990s crime drop affected all geographic areas. The greatest percentage improvements occurred within metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) and especially among large cities with populations over 250,000. All the 25 largest cities experienced noteworthy declines in homicide rates from their peak year (mostly in the early 1990s) to 2001, declines that ranged as high as 73 % for New York and San Diego (Levitt 2004). New York City alone had 17.5 % of all US robberies in 1990, but just 8.4 % in 2005. Remarkably, robbery, always the quintessential urban crime, was no longer correlated with city size by 2000. Figure 2 shows how the urban pattern of robbery rates changed over four decades.

Patterns Of Commission, Victimization, And Violence

In what follows, robbery patterns for the United States as a whole are documented by the use of data from the NCVS on noncommercial robberies. The years 2000–2005 are combined to provide an adequate sample of incidents.

Demographics

Robberies are often committed by groups of offenders. For the period 2000–2005, 18 % of incidents involved two robbers, and 20 % involved three or more. (There has been a pronounced trend toward more solo robberies; just 50 % of robberies in 1980, by 2005 they were up to 62 %.) Such incidents are classified here according to the victim/respondent’s report of the oldest robber’s age or race. Groups of robbers almost always consist of demographically similar individuals, with the partial exception of sex: 11 % of robbery incidents involve at least one female offender, but she teamed up with a man in over one-third of those cases.

In robbery, unlike other types of violent crime, the victim and perpetrator are usually strangers (65 % of incidents) and are drawn from different demographic distributions. The majority of robbers in the United States are male, young (36 % under 21, 74% under 30), and African American (54 %), while the victims are more representative of the US population. There is some tendency for likes to rob likes with respect to age, race, and sex (Cook 1976), but with notable “crossover” – a majority of victims of black robbers are white, and most female victims (37 % of the total) are robbed by males.

Robberies can be classified by location, and for this purpose it is best to get the full spectrum of possibilities, including commercial robberies, which requires UCR data. In 2011, 44 % of all robberies known to the police were on the street and 17 % at a residence. The remaining 39 % were at convenience stores, gas stations, banks, and other commercial locations. The nationwide drop in the robbery rate during the 1990s was concentrated on street robbery, with relative increases in residential and commercial robbery.

Outcomes

When the celebrated bank robber Willie Sutton was asked why he robbed banks, he allegedly replied “because that’s where the money is.” The NCVS provides data only on noncommercial robberies, committed by robbers who generally did not follow Willie Sutton’s putative guidance. Combining all incident reports for 2000–2005 with at least one adult male robber, it turns out that the robbery was unsuccessful in fully one-third of the cases, either because the robber was scared off or the victim had nothing to offer. Cash was stolen in only 29 % of all cases. In the minority of cases that were successful, the median cash stolen was $90. In these and other successful robberies, the loot may include jewelry, clothing, credit cards, household items, and sometimes (in a “carjacking”) a motor vehicle. But only a quarter of successful robberies resulted in theft of items worth $250 or more.

The other proximate outcome is injury to the victim. About half of victims report being physically attacked by the robber (rather than just threatened), and one-fifth require medical treatment. Some victims are seriously wounded or killed. In 2011, the FBI classified 734 murders as robbery related (6 % of all murders), which suggests as an order of magnitude that 2.5 in 1,000 robberies resulted in death that year. The true robbery-murder count is probably higher – one detailed study of Chicago robberies found the police department was conservative in using that classification (Zimring and Zuehl 1986).

Since the greatest threat from robbery is the victim’s serious injury or murder, it is of considerable interest to know what distinguishes those incidents from the great majority in which the victim comes through unscathed (at least physically). One study compared robbery murders (as documented by the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Reports) to robberies, finding similar distributions with respect to prior relationship (primarily strangers) and demographics (Cook 1987, p. 366). But there was one important difference between robbery and robbery murder – the types of weapons used. About two-thirds of robbery murders are committed with guns, while less than one-third of robberies involve guns. Gun robberies are three times more likely to result in the death of the victim than knife robberies, and knife robberies three times more likely than robberies with other weapons (Cook 1987). While it has been much debated whether the type of weapon has a separate causal influence on injury (an “instrumentality effect”), as opposed to merely reflecting the offender’s intent, a variety of evidence favors instrumentality (Zimring 1972; Kleck and McElrath 1991; Wells and Horney 2002). A regression analysis of changes in robbery-murder rates in 43 cities found a close relationship between the robbery rate and the robbery-murder rate, as if the latter were simply a probabilistic byproduct of the former. Every additional 1,000 gun robberies added 4 robbery murders to the city’s total, while 1,000 nongun robberies added just one robbery murder (Cook 1987, p. 373).

Strategic Choices

Observed outcomes of injury and theft are the result of a series of choices made by the robber and his intended victim. The robber (or group of robbers) chooses the victim, the weapon, and the technique, while the victim must decide whether to cooperate or resist. Based on interviews with robbers and other evidence, it is safe to say that robbers’ choices reflect a desire to preempt resistance, secure as much loot as possible, and then make a safe getaway, although actual behavior in these fraught encounters is not necessarily rational (Conklin 1972; Wright and Decker 1997; Jacobs 2000). One useful concept is the “power” of the robber to gain the victim’s compliance (Cook 1976). Power depends on the weapon used by the robber; a gun, by creating a lethal threat at a distance, is most powerful, enough for a single robber to control several victims at once. Accomplices also enhance power, as does skill and experience. A solo offender who lacks a gun or accomplices is more likely to select a woman or older person as victim – a majority of gun robberies, on the other hand, are directed against relatively robust commercial targets (Cook 1980).

A multivariate analysis of NCVS data for 2000–2005 (all robberies committed by an adult male) confirms that the chances of successful theft are greatly enhanced when a gun is used or the robber has accomplices. A gun also enhances the amount of loot in those robberies that are successful, in part because gun robbers are able to choose more lucrative targets (couples, males age 25–54), who might otherwise be in a position to defend themselves. This analysis of the payoff to robbery technique can be used to compute the value of using a gun as opposed to, say, a knife. Other things equal, the likelihood of successful theft increases by 12.5 % points, and the average value of loot in successful robberies almost doubles, when compared to using a knife (the second-best weapon alternative from the robber’s perspective).

Robbers use different methods for gaining compliance depending in part on the circumstances. The standard technique in a gun and knife robberies is to threaten without actually attacking (78 % and 64 % of gun and knife noncommercial cases, respectively), which is usually sufficient to gain compliance. The standard technique in unarmed robberies or robberies utilizing sticks and clubs is to attack physically (over 60 % of cases) and then attempt to take the valuables by force. The chances of injury follow the same pattern, ranging from just 11 % for gun robberies to 36 % for robberies with clubs. Of course when a gun is present and fired, the resulting injury is far more likely to be fatal, and the chances that the victim will be killed are highest for gun robberies (as documented above).

Detailed case studies have provided evidence that the violence in robbery is not necessarily instrumental. The offenders may exploit the situation by raping or otherwise tormenting the victim. In some cases of robbery murder, it would appear that the killing was purely gratuitous or even “recreational,” stemming from the heat of the moment and the interplay between accomplices (Cook 1980; Zimring and Zuehl 1986). Robbery defendants who injured their victims are more likely than others to be arrested for assault following release from prison than are robbery defendants who did not use violence (Cook and Nagin 1979; Cook 1987), suggesting a taste for violence.

The strategic choice framework predicts that drug dealers and other actors in the underground economy would be especially attractive targets, both because the loot is likely to include large amounts of cash and drugs and because victims are not likely to inform the police – although they may attempt to retaliate (Jacobs 2000; Topalli et al. 2002). Crimes of this sort are unlikely to become known unless someone is killed, and indeed, it is common to have a drug connection with robbery murder (Zimring and Zuehl 1986). As observed by one group of criminologists studying drug-dealer robbery, “One of criminology’s dirty little secrets is that much serious crime … takes place beyond the reach of the criminal law because it is perpetrated against individuals who themselves are involved in lawbreaking” (Topalli et al. 2002).

Victims as well as offenders make decisions that influence the outcome. Most important is whether to comply with the robber’s demands and, if not, just how to resist. In the NCVS sample of noncommercial robberies, about one-third of victims attempted to forcefully resist. Resistance is associated with a reduced chance of successful theft, but an increased chance of injury. Victims of gun robbery are less likely to resist than those confronted with other weapons. A practical question often arises of whether it is prudent to resist a robber, but unfortunately it is not possible to extract a clear answer from survey data. Most victims act on the commonsense rule that it is foolish to resist a robber with a gun, and commercial employers often instruct their clerks that if there is a robbery, they should not attempt active resistance.

Interventions

The threat of robbery victimization has far-reaching effects on urban life. The effort to avoid this threat may influence choices about where to live, whether and where to go out at night, the use of public transportation, carrying a weapon, and so forth. A reduction in the robbery threat in a city enhances the residents’ standard of living and may well contribute to the city’s growth and prosperity (Cook and Ludwig 2000). There are a variety of specific measures, both private and public, that hold some promise in this regard, either in reducing the overall robbery rate or in reducing the related harms.

The private efforts to reduce robbery are to a large extent applications of “situational crime prevention” (Clarke 1983, 1995), which attempts to reduce criminal victimization of specific targets by making them less attractive to criminals. The goal is to make it more difficult to complete the crime successfully, reduce the payoff if successful, and increase the risks of arrest and conviction. For especially attractive robbery targets, most notably banks, an array of measures are typically put in place, including guards, surveillance cameras, alarms, and dye packs mixed in with the cash. (Private security against robbery and other crimes is a rapidly growing industry, and there are now as many private guards as there are sworn police officers (Cook and MacDonald 2011).) Studies suggest that convenience stores, which are frequent targets of robbery, can reduce the risk by installing bright exterior lighting and keeping at least two clerks on duty at night (Loomis et al. 2002). A variety of common robbery targets, including all-night businesses and public buses, have attempted to discourage robbery by limiting the amount of accessible cash – and advertising that fact.

One of the most controversial private responses to the threat of robbery is keeping a gun handy. The immediate goal for those who keep or carry a gun for self-protection is to enhance the capacity to resist a robbery, other assault, or criminal intrusion to home or vehicle. But the laws governing gun possession and carrying have taken on great significance in part because of the claim that widespread gun carrying would create a general deterrent to robbery and other assaults that would benefit all. With that in mind, and under pressure from gunrights advocates, most states in the USA have loosened their restrictions on carrying concealed firearms (Vernick and Hepburn 2003), now mandating that all who meet minimum requirements have the right to a concealed-carry permit. These “shall issue” laws have been extensively evaluated with conflicting results (Lott and Mustard 1997; Black and Nagin 1998; Ludwig 1998; Lott 2000). A careful review of the evidence suggests the true effects on crime are almost certainly small and are statistically undetectable given other more powerful forces that influence crime trends (Donohue 2003).

There is less controversy about the public’s stake in robbers’ choice of weaponry; a gun robbery has a greatly enhanced risk of turning deadly when compared with robberies with knives and blunt objects. Gun involvement by young men is closely linked to the prevalence of gun ownership in the community, but there are a variety of regulatory and policing methods that show promise for discouraging gun carrying and criminal use (Cook and Ludwig 2006). One organizing principle for such interventions is to make guns a liability to urban youths and criminals by patrolling against illicit carrying, offering rewards for information on illegal guns, and giving priority to prosecution and sentencing of gun robberies.

More generally, expanding and focusing police resources directed at street crime is a costly but effective method of combating robbery. In England and Wales, the Street Crime Initiative provided funding for anti-robbery policing in 10 of the 43 police-force areas, with large, statistically discernible effects on robbery rates (Machin and Marie 2005). Other studies have provided additional support for the conclusion that additional police suppress crime rates (Levitt 2002; McCrary 2002; Levitt and Miles 2007). The effect sizes are large enough to make a strong case for expanded police funding (Donohue and Ludwig 2007).

Conclusions

When people worry about “crime in the streets,” their first concern is robbery. While the financial losses from robbery are of little consequence overall, the fear of robbery and the actual injuries it causes have a profound effect on the quality of life in certain neighborhoods.

A quick payoff is the allure of robbery for many drug addicts and other criminals. The surest quick payoff is cash, but that is becoming increasingly rare as a means of exchange in the first world nations – except for transactions where preserving anonymity is important. For that reason robbery may focus increasingly on underground markets and as a result become less visible but perhaps more violent. Policies to reduce the scope of the underground market will thus be helpful in the effort to curtail robbery.

Bibliography:

- Baumer E, Lauritsen JL, Rosenfeld R, Wright R (1998) The influence of crack cocaine on robbery, burglary, and homicide rates: a cross-city, longitudinal analysis. J Res Crime Delinquency 35(3):316–340

- Black D, Nagin D (1998) Do “right to carry” laws reduce violent crime? J Legal Stud 27(1):209–219

- Blumstein A (2000) Disaggregating the violence trends. In: Blumstein A, Wallman J (eds) The crime drop in America. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Rosenfeld R (1991) Trend and deviation in crime rates: a comparison of UCR and NCS data for burglary and robbery. Criminology 29(2):237–263

- Blumstein A, Wallman J (2000) The crime drop in America. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Blumstein A, Wallman J (2006) The crime drop and beyond. An Rev Law Soc Sci 2:125–146

- Clarke RV (1983) Situational crime prevention: its theoretical basis and practical scope. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 4. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Clarke RV (1995) Situational crime prevention. In: Tonry M, David P (eds) Building a safer society: strategic approaches to crime prevention. University of Chicago Press, Farrington/Chicago, pp 91–150

- Conklin JE (1972) Robbery and the criminal justice system. Lippincott, Philadelphia

- Cook PJ (1976) A strategic choice analysis of robbery. In: Skogan W (ed) Sample surveys of the victims of crimes. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA

- Cook PJ (1980) Reducing injury and death rates in robbery. Policy Anal Winter 21–45

- Cook PJ (1987) Robbery violence. J Crim Law Criminol 70(2):357–376

- Cook PJ, Khmilevska N (2005) Cross-national patterns in crime rates. In: Tonry M, Farrington DP (eds) Crime and punishment in western countries, 1980–1999. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Cook PJ, Laub JH (2002) After the epidemic: recent trends in youth violence in the United States. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 29. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J (2000) Gun violence: the real costs. Oxford University Press, New York

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J (2006) The social costs of Gun ownership. J Public Econ 90(1–2):379–391

- Cook PJ, MacDonald J (2011) The role of private action in controlling crime. In: Cook PJ, Ludwig J, McCrary J (eds) Controlling crime: strategies and tradeoffs. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 331–366

- Cook PJ, Nagin D (1979) Does the weapon matter? An evaluation of a weapons-emphasis policy in the prosecution of violent offenders. INSLAW, Washington, DC

- Donohue JJ (2003) The impact of concealed-carry laws. In: Ludwig J, Cook PJ (eds) Evaluating gun policy. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Donohue JJ, Ludwig J (2007) More COPS, policy brief 158. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Farrington DP, Langan PA, Tonry M (eds) (2004) Cross-national studies in crime and justice. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington, DC

- Jacobs BA (2000) Robbing drug dealers: violence beyond the Law. Aldine de Gruyter, Hawthorne

- Kleck G, McElrath K (1991) The effects of weaponry on human violence. Soc Forces 69(1991):669–692

- Levitt SD (2002) Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effects of police on crime: a reply. Am Econ Rev 92(4):1244–1250

- Levitt SD (2004) Understanding why crime fell in the 1990s: four factors that explain the decline and six that do not. J Econ Perspect 18(1):163–190

- Levitt SD, Miles TJ (2007) The empirical study of criminal punishment. In: Polinsky AM, Shavell S (eds) The handbook of law and economics, vol 1. North Holland, New York

- Loomis D et al (2002) Effectiveness of safety measures recommended for prevention of workplace homicide. J Am Med Assoc 287:1011–1017

- Lott JR (2000) More guns, less crime, 2nd edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Lott JR, Mustard DB (1997) Crime, deterrence and right-to-carry concealed handguns. J Legal Stud 16(1):1–68

- Ludwig J (1998) Concealed-gun-carrying laws and violent crime: evidence from state panel data. Int Rev Law Econ 18:239–254

- Machin SJ, Marie O (2005) Crime and police resources: the street crime initiative. IZA discussion paper 1853. Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn

- McCrary J (2002) Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime: comment. Am Econ Rev 92(4):1236–1243

- Topalli V, Wright R, Fornango R (2002) Drug dealers, robbery and retaliation. Br J Criminol 42:337–351

- Vernick JS, Hepburn LM (2003) State and federal gun laws: trends for 1970–99. In: Ludwig J, Cook PJ (eds) Evaluating gun policy. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Wells W, Horney J (2002) Weapon effects and individual intent to do harm: influences on the escalation of violence. Criminology 40(2): 265–296

- Wilson JQ, Boland B (1976) Crime. In: Gorham W, Glazer N (eds) The urban predicament. The Urban Institute, Washington, DC

- Wright RT, Decker SH (1997) Armed robbers in action. Northeastern University Press, Boston

- Zimring FE (1972) The medium is the message: firearm calibre as a determinant of death from assault. J Legal Stud 1:97–124

- Zimring FE (2007) The great American crime decline. Oxford University Press, New York

- Zimring FE (2012) The city that became safe. Oxford University Press, New York

- Zimring FE, Zuehl J (1986) Victim injury and death in urban robbery: a Chicago study. J Legal Stud 15(1):1–40

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.