This sample School Structural Characteristics and Crime Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Schools’ capacity to implement effective prevention strategies and to establish well-ordered communities is likely to be greater in schools that are not overwhelmed by having a high proportion of the students at risk. In this research paper, we discuss decisions primarily made outside of the school building that influence the demographic composition of schools and the number and types of other students to whom a child is exposed. Externally determined factors (e.g., finances, physical features of building, school size, and student/teacher ratio) also determine resources available in the school and define patterns of interaction broadly speaking. Here we will focus on school-district policies influencing the student composition of schools and school size.

Specifically, we will consider the extent to which school or school-district decisions regarding how students are organized for instruction (e.g., academic or behavioral tracking or departmentalization) further narrow the characteristics of other students to whom youths will be exposed. Importantly, these decisions determine the pool of youths from which highly influential peers will be selected as well as the dominant peer culture in the school. These structural characteristics potentially influence crime-producing mechanisms.

We find that the concentration of different types of students in a school has important implications for the amount of crime in the school: The grade levels included in the school or average age of the students in the school, the percentage male students, the social class composition, and the racial and ethnic composition of the schools are related to measures of problem behavior. Further, some policies that alter the composition of classes, grades, or schools have been shown to reduce problem behavior: Keeping sixth graders in elementary schools as opposed to moving them to middle schools reduces disciplinary infractions, and retaining students in grade increases conduct problems both for the “old-for-grade” students and for non-retained students. We find little support for the idea that the size of the school per se matters for reducing school crime.

We begin this research paper with a summary of research related to school size and student demographics as they relate to school crime and disorder. We then discuss school policies and practices that are likely to alter the types of students with whom a student is likely to be exposed. We end with a discussion of implications for policy and research.

School Ecology

One category of school structural characteristics is “school ecology.” Very few studies have examined the influence of several potentially important aspects of school ecology including school finances and the physical features of the school building. By contrast, many studies include a measure of school size – number of students in the school or in the grade. Our discussion will therefore focus on school size, providing a summary of the literature and some new results.

School size is thought to have a major influence on the internal organization of schools and on subsequent student outcomes. Lee et al. (1993) suggest that larger schools are likely to have increased capacity to tailor programs and services to meet the diverse needs of students in the school. The extreme example of low specialization is a one-room schoolhouse in which one teacher teaches all students all day. In small schools, the typical teacher teaches a smaller number of different students and gets to know these students well. Students in such schools may develop a greater sense of trust in the adults and be more likely to communicate potentially dangerous situations to them. Large schools are likely to be organized more bureaucratically and to involve more formalized social interactions among members of the school population. As a result, communication may be less frequent or less direct, cohesiveness may be reduced, management functions (including the management of discipline) may become less nuanced, and individuals may share less of a common experience in the school. Alienation, isolation, and disengagement may result. All of these mechanisms are plausible but speculative.

As it turns out, school size has not received much focused attention in research on schools and crime. However, many studies have included a measure of school size as a control variable when focusing on the effects of other aspects of school climate. Cook et al. (2010) summarized the associations between measures of school size and problem behavior in school-level and multilevel studies. They found nine school-level studies based on data from seven different data sources. In the studies that reported an unambiguous association between school size and a measure of problem behavior, the conclusions differed depending among other things on the measure of problem behavior used. Positive associations between school size and measures of minor misbehavior were reported for the High School and Beyond high school data and the National Education Longitudinal Study [NELS] eighth graders, but the association with more serious forms of misbehavior was not statistically significant. In another data source (Safe School Study), school size was not significantly related to student victimization but was positively related to teacher victimization. That study also showed that the effect of school size on teacher victimization is mediated by aspects of the school social organization and culture. No significant relationship with school size was found in a study of middle schools in Philadelphia.

The multilevel studies summarized provided no support for the “smaller is better” viewpoint. Fifteen different research reports based on nine different data sources were summarized. In these studies, which generally controlled for community characteristics as well as characteristics of the students who attend the school, only one data source (NELS tenth graders, as reported in Stewart 2003) produced a significant positive association between school size and a measure of problem behavior, and the measure of problem behavior used in this study was unusual because it contained mainly school responses to misbehavior (e.g., being suspended or put on probation) rather that actual youth behavior. Hoffmann and Dufur (2008) also reported on the association of school size and a broader measure of problem behaviors including substance use, arrest, and running away using the NELS tenth grade sample and found no significant association. Reports from a sample of Israeli schools containing seventh and 11th grades documented a positive association between average class size and student victimization, but no significant association with school size. One of the multilevel studies reported a significant negative association between school size and student victimization, but this sample included only rural schools located in New Brunswick, Canada, whose average size was 39 and 53 students, respectively, for sixth and eighth grade. A recent study by Gottfredson and DiPietro (2011) found that, net of individual-level risk factors and confounding characteristics of schools and their surrounding communities, more students per teachers and a higher number of different students taught by the average teacher were related to higher student victimization rates, but larger school size was significantly related to lower student victimization rates. Cook et al. (2010) concluded that most of the multilevel studies suggest that school size is not reliably related to student problem behavior once characteristics of the students who attend the schools are controlled.

However, the studies summarized often reported on the association between school size and problem behavior from models that may provide too conservative a test. The student characteristics that are controlled in the multilevel studies are often exactly those student characteristics that Lee et al. (1993) hypothesized to be influenced by school size (e.g., school attachment, involvement, perceived positive social climate). Also, most of the associations with school size reported in the studies are from models that partial out influences not only of the communities in which the schools are located and the average demographic characteristics of the students attending the schools but also of other school climate characteristics such as school culture and the administration/management of discipline, hypothesized to mediate the influence of school size on student outcomes. For example, Hoffmann and Dufur’s (2008) study reported a negative association between school size and delinquency in the NELS data, but the equation also contained measures of “school quality,” a composite measure assessing youth perceptions of their school as fair and their teachers and fellow students as caring and trustworthy. Unfortunately, many of these reports did not report the association of school size with problem behavior in models that do not control for potential effects of school size.

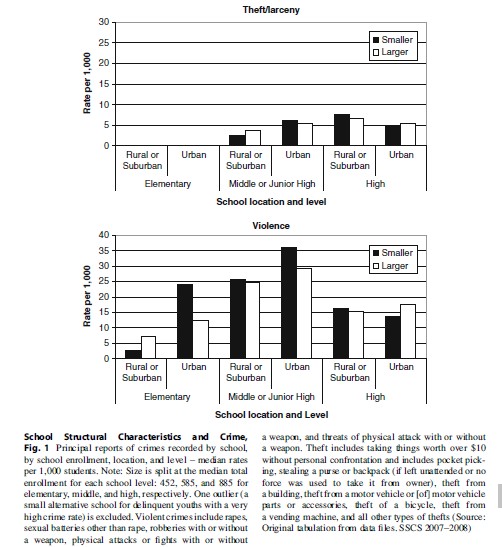

New results. We analyzed data from the 2007–2008 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSCS; Neiman and DeVoe 2009) in an attempt to establish baseline descriptive results on how school size relates to school crime. Principals were asked how many incidents of various types of crime had occurred at school during the last school year. They were asked about violent crimes (rape, sexual battery other than rape, physical attack or fight with or without a weapon, threat of physical attack with or without a weapon, and robbery with or without a weapon) and about theft and larceny. We calculated rates per 1,000 students for each school. Because school size is highly related to location and level, it is necessary to look at the association of crime rates and enrollment while controlling for these factors.

Figure 1 shows median rates per 1,000 students for theft/larceny and violent crimes, according to school principals. The figures make clear that crime rates are not systematically related to school size within level and location. However, there is some suggestion that the association between size and principal reports of crime differs according to type of crime, level, and location: In urban locations, principals in smaller elementary and middle schools report more violent crimes. This is not the case in rural/suburban schools or in urban high schools.

We conclude that school size is not generally related to principal reports of school and that whatever differences observed favor larger schools over smaller schools.

It is likely that the ratio of adults to students rather than the actual number of students in the school is related to problem behavior. Five of the studies summarized in Cook et al. (2010) looked at the association of problem behavior to student/teacher ratio. Only one of the five studies reported a significant relationship: Gottfredson and DiPietro (2011), in a multilevel study using data from the National Study of Delinquency Prevention in Schools, reported a positive association of student/teacher ratio and personal but not property crime victimization. That study reported that higher levels of social capital, as measured by student consensus about normative beliefs, partially mediated the effects of student/teacher ratio on personal victimization. We believe that a more sensitive measure of adult presence would be the ratio of all adults (rather than just teachers) to students. Many schools use parent volunteers and teacher aides in addition to teachers to help maintain order. The ratio of the total number of adults to students would reflect variability in the use of such auxiliaries. Unfortunately, no studies have reported on this association.

As far as we know, there are no intervention-based studies of how school size affects school crime. Case studies of instances in which an established school is divided in smaller units are available, but they almost never assess effects on crime, and they do not provide a clean test of the effects of changing school size because other factors (such as the curriculum, aspects of the physical space, and school finances) are always altered simultaneously.

Milieu

The SSCS data show that rates of problem behavior differ with demographic characteristics. Middle schools have higher rates of delinquency than elementary or high schools (the partial exception is substance use, which increases through high school). Schools with 50 % or more minority enrollment experience higher rates of violence than majority white schools (Nolle et al. 2007). Socioeconomic status of the student body is also associated with delinquency rates (Gottfredson et al. 2005).

More interesting from a policy perspective is the extent to which the mix of students in the school or the classroom influences the likelihood that any given student will misbehave. The mechanisms of deviant peer influence are both direct and indirect. The direct effects may arise as a result of deviant peer influence: learning and imitation, social reinforcement for deviant acts, and the creation of opportunities for deviant activities (Dishion and Dodge 2006). It may also be due to the presence of social norms that support (or at least appear to youth to support) delinquent behavior. All these mechanisms are relevant for involvement with delinquency both in and out of school, including drugs and alcohol, and participation in gangs. The indirect effects may come about as a result of the dilution of authority – a teacher who can manage one or two disruptive students may lose control of the classroom when there are more than two. The same phenomenon can occur at the school level, where a high “load” of troublesome students may swamp the mechanisms of control in the corridors, cafeteria, lavatories, and grounds.

Given the real possibility of peer influence, the actual behavior of youths with a given propensity to deviant or criminal activity may well depend on whom they encounter in their classes and in the other locations in the school. A variety of policies are relevant to influencing the mix of students. At the level of the school district, the distribution of students among schools will be influenced by which grade spans are included in the middle schools, the extent to which low-performing students are held back, and whether school assignments are tied largely to place of residence or tailored to promote integration or parental choice. For a given pattern of assignments to schools, the number and characteristics of students who are actually in the building on a school day will depend on absenteeism and use of out-of-school suspension. And for a given population of students who are actually attending the school on any given day, social influence will likely be mediated by policies that influence the extent to which deviant students are concentrated, such as in-school suspension or academic tracking.

Cook et al. (2010) summarized the results from 18 multilevel studies based on 14 datasets showing associations between the milieu of the school and measures of problem behavior, controlling for individual-level demographics as well as for related characteristics of the communities from which the student body is drawn. These studies showed that the grade levels included in the school or average age of the students in the school, the percentage male of students, the social class composition, and the racial and ethnic composition of the schools are related to measures of problem behavior. These associations sometimes did not reach statistical significance, but they were nearly always in the expected direction. Here we discuss several of the strongest studies relevant to evaluating the impact of policy choices concerning grade span, grade retention, truancy prevention, racial segregation, and use of alternative schools.

- Grade span. One recent study demonstrates that the grade composition in a middle school influences the rates of misbehavior of the students. A generation ago, most elementary schools included sixth grade, but now most sixth graders attend middle school. Using a quasi-experimental approach, Cook et al. (2008) compare the school records of North Carolina students whose sixth grade was located in a middle school with those whose sixth grade was in elementary school (the sample of sixth grades in middle school was trimmed to match the sixth grades in elementary school in several dimensions). While the two groups of students had similar infraction rates in fourth and fifth grades, those who moved to a middle school for sixth grade experienced a sharp increase in disciplinary infractions relative to those who stayed in elementary school. More interesting, perhaps, is that the elevated infraction rate persisted through ninth grade. A plausible interpretation of these findings is that sixth graders are at a highly impressionable age, and if placed with older adolescents, they tend to be heavily influenced by their inclination to break the rules. This example of negative peer influence is quite large and extends to all types of infractions, including violence and drug violations.

- Retention policies. The age mix in a school is closely related to the grade span, but that is not the only determinant; the school district’s retention policies also play a role. In response to high-stakes accountability programs (including No Child Left Behind), many school systems have ended social promotion for students who fail end-of-grade tests, thus increasing the number of old-for-grade students. Entry-level at-risk students are often held back for a year before making the transition to second grade. The effect of retention on behavior of the retained students has been extensively studied. Most studies have focused on academic outcomes: Meta-analyses of this literature conclude that the long-term effect on academic achievement is null or negative, with a greatly elevated risk of dropping out (Jimerson et al. 2006). Hence, given the robust general finding that students with academic difficulties are more prone to antisocial behavior (Nagin et al. 2003), it is not surprising that grade retention appears to increase conduct problems. One of the most sophisticated studies, using Richard Tremblay’s longitudinal data on Montreal school children, found that the effect of grade retention on classroom physical aggression (as measured by teacher reports) is conditioned by the developmental history of the child: Those showing no aggression or chronic aggression levels were not affected, whereas those whose trajectory of aggression was declining over time increased their aggression more so if retained than if not retained (Nagin et al. 2003).

There has been less attention to the contextual effect of having old-for-grade students in the classroom and school. One exception is a recent study that uses a comprehensive data set of North Carolina students. Muschkin et al. (2008) conduct a cross-sectional analysis of infraction rates by seventh graders, finding that the prevalence and incidence of infractions increase with the prevalence of retained students (students who were retained at least once in the previous 3 years) and the prevalence of old-for-grade students who were not retained during that 3-year period. These results hold after they controlled for various characteristics of the student body and the schools and the inclusion of district fixed effects. The authors also find evidence that susceptibility differs among types of students; in particular, the old-for-grade seventh graders were themselves especially susceptible to the influence of the concentration of other old-for-grade students in their school. Similar results were found when the outcome variable was the likelihood of being suspended.

- Truancy prevention. The mix of students who are in the school building on any given day will be affected by absenteeism and tardiness. School attendance laws require that youths between specified ages (e.g., 7–16 in North Carolina and 5–18 in New Mexico) attend school, with possible exceptions for home schooling. This is a legal obligation for which both the child and parents are liable. In many school districts, however, these laws are widely flouted. For example, the absentee rate in DC public high schools in the 2006–2007 school year averaged 17 %.

The rate of unexcused absence determines not only the number of students in the school building but also the behavioral propensities of those students. Chronic truants are not a representative sample of the student body but rather tend to come from dysfunctional families and be at risk for delinquency, violence, and substance abuse (McCluskey et al. 2004). It is also true that chronic truancy engenders academic problems and is associated with failure to graduate from high school and a variety of poor life outcomes, including involvement with serious crime. As a logical matter, then, programs that are effective in improving attendance rates may have several effects. First, if they get delinquent youths off the street and into school, the result may be reduced crime rates in the community. Indeed, communities concerned about the daytime crimes committed by truants have increasingly enlisted the police and the juvenile court to combat truancy. Second, effective truancy-prevention programs may come at the cost of higher crime rates within the school. And third, if at-risk youths are persuaded to attend school more faithfully, the long-term result may be to improve their chances of graduation and subsequent success.

A number of school-based programs have been evaluated in part by their effect on school attendance. Unfortunately, there are no studies, insofar as we know, that evaluate the effect of attendance-promoting programs on school crime rates or overall (community plus school) crime rates.

- School desegregation. In compliance with the 1954 Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education, federal courts issued a series of desegregation orders to public school districts. These orders forced a considerable increase in the extent to which African American students attended school with whites during the 1960s and 1970s. A vast literature on the effects of school segregation and desegregation has focused on academic outcomes. The results of this research offer support to the conclusion that integrated schools promote black achievement and increase black high school graduation rates, college attendance and graduation rates, and occupational success (LaFree and Arum 2006). A persuasive quasi-experimental study of the effect of desegregation plans found that they reduced black dropout rates by 2–3 % points, with no detectable effect on whites (Guryan 2004). Given the tight link between academic success and school behavior, it is entirely plausible that the degree of segregation has a direct influence on delinquency in schools. But we are not aware of any direct evidence on the subject; segregation studies have not used school crime as an outcome variable. There have been two persuasive studies concerning the effects of segregation on crime outside of school. LaFree and Arum (2006) analyzed the incarceration rates for black males who moved to a different state following school. For any given destination state, they found that those who moved from a state with well-integrated schools had a substantially lower incarceration rate than those who moved from a state where the schools were more segregated. A more recent study (Weiner et al. 2009) utilizes a quasi-experimental approach in which the court desegregation orders serve as the experimental intervention: They report that these orders reduced black and white homicide victimization rates for 15–19-year-olds. The authors explore several mechanisms that may account for this result, including both the direct effects of changing the mix of students in the schools and indirect effects associated with police spending and relocation of some white students. In any event, since all but a handful of these homicides occurred outside of school, we are still waiting for direct evidence on crime in schools.

- Alternative schools. A recent survey found that 39 % of public school districts administered at least one alternative school for students at risk of educational failure. As of October 2000, 613,000 students were enrolled in these schools, 1.3 % of nationwide total enrollment. Urban districts, large districts (those with 10,000 or more students), districts in the Southeast, districts with high minority student enrollments, and districts with high poverty concentrations were more likely than other districts to have alternative schools and programs for at-risk students. Despite the widespread use of these schools as a means of removing antisocial and violent students from the regular classrooms, there have been no systematic studies of the effects on school crime rates. The effects on the behavior of youths who are given alternative-school placements have been studied, with mixed results. Indeed, there is unlikely to be any generic answer, since effects will depend on the quality of the programming and on which students are selected. Best-practice judgments tend to rely on expert opinion rather than on evaluation studies with strong designs.

- Grouping within schools. Academic tracking is nearly universal in US secondary education. The attraction of separating students into tracks that are more or less demanding academically is the belief that this is the best way to tailor coursework to the differing background, ability, and motivation of the students. Tracking tends to have the result of concentrating minorities and students from lower socioeconomic status households in certain classrooms. Given the strong association between academic success and delinquency involvement, it also has the effect of concentrating crime-prone students, setting the stage for negative peer influence.

As a device to improve academic progress, tracking has had more detractors than advocates among education specialists. The evidence base is thin: Most notably, Mosteller et al. (1996) identified only ten randomized experimental evaluations comparing the performance of students in tracked (homogeneous) and untracked (heterogeneous) classrooms. When these studies were combined, the best estimate was a zero difference in average academic performance. Still thinner is any evidence on how tracking affects misbehavior. Thus, we conclude that the possibility of deviant peer influence due to tracking is plausible but unproven.

Conclusion

School reform is typically shaped by theories of how to improve students’ academic performance. But to the extent that school safety is an important goal, somewhat distinct from academic progress, the potential impacts on safety should be considered in any evaluation.

One of the most prominent reform efforts since 2001 has been the campaign funded largely by the Gates Foundation to create small high schools. While that effort was abandoned in 2008 as a result of disappointing results on academic progress, it would also be of interest to know the effect on school crime and juvenile delinquency. Given the fact, reported here, that small schools are not systematically safer than large schools (controlling for urbanicity and grade level), it appears doubtful that smaller is better in this domain.

There is very good reason to believe that the mix of students who are assembled in a school or any one classroom may influence the behavior of all. Two relevant mechanisms are deviant peer influence and “resource swamping,” both implying that overall crime rates within school may increase in nonlinear fashion with the addition of deviant students to the mix (Cook and Ludwig 2006). This concern is relevant in evaluating policies regarding grade retention, truancy prevention, use of suspension and expulsion, use of alternative high schools, and even academic tracking. In each case, however, we found that relevant evaluations were lacking.

Implications For Research And Policy

Crime rates differ widely among schools. Experimental evidence suggests that the crime involvement of any given student at risk is influenced by the school that he or she attends. That fact motivates our scientific quest to find the school structural determinants of criminal activity by school-aged youths.

The school climate studies revealed sturdy associations between measures of school climate and measures of student delinquency, victimization, substance use, or other forms of problem behavior.

A starting point in accounting for interschool differences in crime is the criminal propensities of the students. Schools in which many of the students are active delinquents outside school start with a far greater challenge than those in which the students are largely law-abiding. The school crime rate of a student body with high crime propensity may be greater than the sum of the parts for two reasons. First, if the school lacks the adult resources to manage the “load” of misbehavior, then the school may become progressively more chaotic, spinning out of control. Further, delinquent and deviant youths may have a negative influence on each other and other students as well, further amplifying the problem. As noted in earlier discussion of the mechanisms involved in the production of crime and the features of schools that might influence these mechanisms, decisions that influence the demographic composition of schools are important because they determine the prevailing cultural beliefs in the school as well as the pool of youths from whom friends can be selected. In short, the crime rate in school is not just the sum of the parts but does reflect the ecological effects of the mix of students in the building. Schools and school districts have a good deal of control over the makeup of the student body. Schools can be based on neighborhood residential patterns or integrated across race and class. The grade span for elementary and middle schools can be adjusted. Truancy and dropout prevention programs can be pursued with more or less vigor and troublesome students reassigned. Whether failing students are retained in a grade or given a social promotion influences the extent of age homogeneity within classrooms. Students who are enrolled in the school can be tracked on the basis of academic potential or mixed together and so forth. This array of policy choices has the potential to influence the “load” on teachers and other adults and the opportunity for deviant peer influence. Some of these policies have been evaluated for these ecological effects, but the evidence base is quite thin.

We also note that most of the evaluations of policies that affect the mix of students – truancy and dropout prevention, alternative schools, tracking, grade retention of failing students, and so forth – only consider the effect on the students who are targeted and fail to consider the ecological effects. But secondary effects on other students may be quite important and should be included when it is possible to implement a comprehensive study.

Finally, we noted that evidence does not support the conclusion that smaller schools are more effective for limiting problem behaviors than larger schools, but research suggests that conditions that make a school environment “feel” smaller and more communally organized are related to levels of problem behavior.

References

- Carrell SE, Hoekstra ML (2008) Externalities in the classroom: how children exposed to domestic violence affect everyone’s kids. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper no.14246. Available at http://www.nber.org

- Cook PJ, Gottfredson DC, Na C (2010) School crime control and prevention. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J (2006) Assigning youths to minimize total harm. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE (eds) Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: problems and solutions. The Guildford Press, New York, pp 122–140

- Cook PJ, MacCoun R, Muschkin C, Vigdor J (2008) The negative impact of starting middle school in sixth grade. J Policy Anal Manage 27:104–121

- Dishion TJ, Dodge KA (2006) Deviant peer contagion in interventions and programs: an ecological framework for understanding influence mechanisms. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE (eds) Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: problems and solutions. The Guilford Press, New York, pp 14–43

- Gottfredson DC, DiPietro SM (2011) School size, social capital, and student victimization. Sociol Educ 84(1):69–89

- Gottfredson GD, Gottfredson DC, Payne AA, Gottfredson NC (2005) School climate predictors of school disorder: results from a national study of delinquency prevention in schools. J Res Crime Delinq 42:412–444

- Guryan J (2004) Desegregation and black dropout rates. Am Econ Rev 94:919–943

- Hoffmann JP, Dufur MJ (2008) Family and school capital effects on delinquency: substitutes or complements? Sociol Perspect 51:29–62

- Jimerson SR, Pletcher SMW, Graydon K, Schnurr BL, Nickerson AB, Kundert DK (2006) Beyond grade retention and social promotion: promoting the social and academic competence of students. Psychol Sch 43:85–97

- LaFree G, Arum R (2006) The impact of racially segregated schooling on the risk of adult incarceration rates among U.S. cohorts of African-Americans and whites since 1930. Criminology 44:73–103

- Lee VE, Bryk AS, Smith JB (1993) The organization of effective secondary schools. In: Darling-Hammond L (ed) Review of research in education. American Educational Research Association, Washington, DC, pp 171–267

- McCluskey CP, Bynum TS, Patchin JW (2004) Reducing chronic absenteeism: an assessment of an early truancy initiative. Crime Delinq 50:214–234

- Mosteller F, Light RJ, Sachs JA (1996) Sustained inquiry in education: lessons from skill grouping and class size. Harv Educ Rev 66:797–842

- Muschkin C, Glennie B, Beck A (2008) Effects of school peers on student behavior: age, grade retention, and disciplinary infractions in middle school. J Policy Anal Manage 27:104–121

- Nagin DS, Pagani L, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F (2003) Life course turning points: the effect of grade retention on physical aggression. Dev Psychopathol 15:345

- Neiman S, DeVoe JF (2009) Crime, violence, discipline, and safety in U.S. public schools: findings from the school survey on crime and safety: 2007–08 (NCES 2009-326). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, DC

- Nolle KL, Guerino P, Dinkes R (2007) Crime, violence, discipline, and safety in US public schools: findings from the school survey on crime and safety: 2005-6 (NCES 2007-361). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, DC

- Stewart EA (2003) School social bonds, school climate, and school misbehavior: a multilevel analysis. Justice Q 20:575–604

- Weiner DA, Lutz BF, Ludwig J (2009) The effects of school desegregation on crime. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper no.15380. Available at http://www.nber.org

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.