This sample Sentencing As A Cultural Practice Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Most of the scholarly literature on sentencing is written from a legal or philosophical perspective. Legal scholarship analyzes sentencing law. Philosophical work analyzes the normative debates about the aims of punishment in a liberal democratic society. This research paper examines sentencing as a cultural practice. Culture refers to sets of shared meanings or collective representations. To study culture is to examine the ways in which meanings are defined, enacted, mediated, communicated, and shared by a range of actors and audiences. A cultural analysis of sentencing is a study of how certain important meanings are represented. These include representations of moral boundaries, of justice, and of legitimate decision-making processes. David Garland argues that penal institutions have important cultural dimensions and consequences which shape penal policies and practices.

Cultural categories, habits and sensibilities are embedded in and constitutive of our political and economic institutions. (Garland 2006)

A cultural understanding of sentencing seeks to understand sentencing as a collective practice which involves nonjudicial actors as well as judges. Garland distinguishes between different uses of the term “culture” in the sociology of punishment. On the one hand, “culture” describes a particular web of meanings which can be found empirically, for example, the local court culture of a particular jurisdiction which is shared and reproduced by the regular court actors. In this sense a culture is a more or less bounded set of customs, values, habits, and beliefs. On the other hand, “culture” can also be used analytically to describe ways of making meaning in a social setting, for example, how the sentencing process defines what it means to make just decisions about the allocation of punishment. In this sense cultural analysis is distinct from other forms of analysis, for example, political. A cultural analysis focuses on the creation of meaning, and a political analysis will focus on how a particular meaning becomes powerful and silences other potential meanings. This research paper focuses on the latter use of the concept; it provides a cultural analysis of sentencing rather than describing a particular sentencing culture (Yanow 1996).

There are three important ways in which a cultural approach provides a better understanding of sentencing.

First sentencing articulates the moral boundaries of society. In allocating different sorts of punishment to different sorts of offender, sentencing defines the boundaries between order and disorder, between the respectable and the disreputable, between the pure and the polluted, between good and evil, and between reason and emotion. Whatever particular forms punishment takes, it always performs this cultural task of ordering, separating the sacred from the profane (Smith 2008; Douglas 1966). Thus, sentencing helps to promote social solidarity.

Second, sentencing decision making performs and defends a particular definition of “justice.” A distinctive narrative of justice underpins sentencing decision making in most common law jurisdictions, even in those US states with sentencing guidelines. This narrative both purports to describe how judges reach their sentencing decisions and also provides a normative justification for these decisions. This narrative, which is commonly known as “individualized sentencing,” is described below.

Third, sentencing reproduces shared sets of meanings. It is a social practice and not just the action of an individual judge. Sentencing decision making, like other social action, is largely habitual, taken for granted, and unreflective. This does not mean that sentencers have anything less than a thoroughly professional, conscientious, and serious-minded approach to their work. But like all professionals, they work within a framework of meanings, perceptions, values, and motives that for most of the time are unquestioned. They are the taken-for-granted assumptions on which the challenging job of sentencing is based. Bourdieu calls this the “habitus” (Hutton 2006). Individualized sentencing forms the habitus for judges; it refers to the unquestioned, taken-for-granted cultural framework which defines both the way that decisions are made and also the way that these decisions are justified.

The chapter proceeds by looking at each of these three cultural tasks and in the final section analyzes the challenges to the dominant cultural approach to sentencing.

Boundaries Of Moral Tolerance

From a broader Durkheimian perspective, sentencing decision making enacts deeper cultural meanings about moral boundaries which both bind society together and at the same time identify fractures and divisions (Smith 2008). Punishment expresses ideas about the sacred and the profane, about moral pollution, and about atonement and evil. As Philip Smith argues, “we can understand these basic, protean, cultural categories running through and under what appear to be more rational modern scientific instrumental or bureaucratic tendencies.” Sentencing performs an “othering” function in all communities. There cannot be a community, “people like us,” without people who are not like us. Sentencing therefore both includes and excludes. For Smith, following Durkheim, all societies have crime and punishment but the cultural meanings of these vary. They are invoked and put into practice in a political context and are always contested and contestible.

In allocating punishment, sentencing performs the job of defining these moral boundaries. In a broad sense, this involves invoking binary classifications such as good/evil, sacred/ profane, pure/polluted, safe /dangerous, and insider/outsider. Sentencing decision making involves drawing these black-and-white distinctions, but it also involves more subtle shading which blurs the apparently sharp binary division and produces distinctions which are not as clearcut in practice as they may appear in cultural theory.

Criminalization and the decisions of police officers and prosecutors about whether to proceed further with a reported incident patrol the boundaries between criminal and noncriminal. Sentencing is really about the shape and gradation of the negative side of this binary divide and also sometimes about the potential for an offender to shift back across to the positive side. Sentencing is about separating the good guys from the bad guys. It is also about establishing just how bad the bad guys are, about the possibility or impossibility of bad guys transforming themselves into good guys, and about what opportunities may be offered to help them to change.

In sentencing, the distinction between prison and the community is symbolically crucial. In those jurisdictions where the death penalty has been abolished, prison is the most severe sanction now available. In both England and Wales and Scotland, legislation provides that custody should only be used as a last resort where no other sanction would be appropriate Padfield (2011), Tombs (2004). The removal of the individual from the community by the State signifies both the power of the state and the subjugation of the body of the individual offender. The decision to imprison has therefore a qualitatively different significance from those other sanctions which deprive the offender of limited amounts of time, money, or association.

Aside from the custody/community tension, there are other important meanings being generated in sentencing. At the most serious end of the scale, there is a debate about how long serious offenders need to be imprisoned and the relativities both within offences (e.g., how to define different levels of seriousness of rape) and between offences (e.g., a rape and a serious assault). At the lower end, there are decisions about the boundary between fines and community sanctions (which have received less attention because of the symbolic and fiscal implications of custodial sentences) and the debates about whether fines are simply a form of economic regulation which carry little of the stigma of the other sanctions. The fine delivers pain while impacting minimally on the freedoms of movement, speech, association, and political participation that we call “liberty.” The regulation of conduct virtually through automated bank transfers may be seen as a dystopian nightmare by some (Aas 2005), but it could also be the desirable freedom of a consumer society where we choose whether or not to conform and pay the price if we decide not to, literally the price of freedom (O’Malley 2009).

While it is true to say that the implementation of the criminal law performs the function of dividing conduct into acceptable and unacceptable, in practice the boundary is more accurately described as a sloping shelf, than a clearly defined wall. The boundary relates strictly speaking to actions, people can move from one side to the other. However, in practice we tend to think about criminals rather than criminal acts, and the label of criminal may persist independently of particular actions. Sentencing plays the important cultural function of defining the shape and texture of the boundary between “them and us” which turns out not to be a sharp binary distinction but a much more amorphous and liminal territory. The prison population is clearly visible “out there,” but there are crowds milling around the prison walls.

In this section we have seen that punishment is about drawing distinctions between insiders and outsiders and that sentencing is the performance of this cultural process of ordering. So sentencing is not about exclusion or inclusion but about both. Sentencing can support discourses of redemption, desistance, and rehabilitation, but it also needs to support discourses of punishment, pain, and exclusion. Sentencing therefore cannot choose between rational and emotional responses to offending; it has to be able to sustain both of these approaches.

The Discourse Of Individualized Sentencing

The discourse of individualized sentencing may be summarized as follows. In reaching their decision, judges take into account all of the facts and circumstances of the individual case. Each case is composed of a very large number of relevant factors and is therefore held to be unique. No two cases are exactly the same. Judges reach their decision by an “instinctive synthesis” (R v Williscroft [1975]VR292 at 300) of these myriad factors. By defining each case as unique, this approach is able to remain silent about consistency, another important feature of liberal definitions of justice. So individualized sentencing performs a particular sort of “justice” which privileges the specificities of an individual case over the demands of consistency. Judges use the discourse of “individualized sentencing” to defend a particular approach to making just decisions. “Individualized sentencing” therefore performs a particular cultural logic which both produces “justice” in sentencing and defends this definition against its potential critics, primarily those who argue that it is possible to determine similarities between cases and that it is ethically important to treat similar cases in a similar way. “Instinctive synthesis” has a transcendent quality because it is not susceptible to further rational explanation. There is thus an element of the sacred in the discourse of individualized sentencing. Intuitive synthesis presents sentencing decision making as being beyond the control of human agency, a function which can only be performed by those holding the office of judge.

Sentencing As A Social Practice

Sentencing is collective action made possible by shared cultural meanings and understandings. The actions of other criminal justice actors in the process play a part in shaping the judicial sentencing decision and are also shaped by this approach to decision making. Sentencing is a stage in the criminal justice process. Judges deal with cases which have been constructed by other actors. Each case proceeds through several processes of translation. The term “translation” (Latour 2005) is used here to make the point that what constitutes a “case” changes, as it passes through each stage of the process. Actors interpret information which is presented to them by others, act on this information in pursuit of their professional requirements, and pass this information on to the next set of actors in the next stage of the process. Cases are therefore constructed out of witness accounts, police reports, prosecutors’ professional practices, reports written for the court by social workers, medical professionals, forensic scientists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and defense pleas in mitigation (Castellano 2009; McNeill et al. 2009; Sudnow 1965; Tata 2007; Yngvesson 1989). When judges pass sentence, their understanding of the case comes from reading documents and sometimes listening to evidence and argument. They have no unmediated access to the event that gave rise to the case. Thus, by the time that the case has reached the sentencing stage, it is defined in a particular way which already limits the options open to the judicial decision maker. The case is a more or less familiar narrative which prompts a more or less familiar ending.

So sentencing is not simply about judges nor is it solely about individual cases nor about individual decisions. Sentencing is a social practice and also a cultural practice.

Sentencing is the social and cultural performance of a particular definition of justice. The term “performance” is chosen deliberately to emphasize the importance of action. Justice is not something which only exists in philosophical debates or in sentencing texts. Justice has to be enacted every day in the decision-making processes of actors working in the criminal justice system. One of the most important cultural tasks of the sentencing process is to persuade audiences that sentences passed by the court are just. Sentencing is therefore about the creation of meaning performed by an interpretive community. Sentencing is a means of communicating, persuading, convincing, justifying, and providing an account of decisions which have a profound impact on individual offenders and carry powerful messages both about the kind of society we live in and the kind of society we might want to create.

Philosophical Aims Of Sentencing

From a philosophical perspective, the main issue related to sentencing is the moral question of how punishment can be justified and what should be the aims of punishment (Honderich 1989). The infringement of individual liberty and/or the imposition of pain by the state requires to be both lawful and morally justifiable. Debates range about whether punishment should be backward looking and impose punishment proportionate to the seriousness of the offence ((just deserts) or whether punishment should be forward looking and seek to have an impact on reducing crime by deterring individuals or the general population, by making reparation to the community or the victim, by rehabilitating the offender, or by protecting the public. Most jurisdictions adhere to these aims at a general systemic level, but in terms of sentencing decision making, it is not clear what impact, if any, the pursuit of aims plays in selecting the type and severity of sentence in individual cases. This “cafeteria” approach (Ashworth 2010) offers great flexibility as any sentence can be fitted into one or more of these justifications. It enables sentences to be justified on a case-by-case basis. However, the flexibility of this suite of aims is also a weakness. A sentence which appears to be fair in comparison with sentences for similar cases may not be an appropriate sentence for protecting the public or for enabling the rehabilitation of the offender. The cafeteria approach does not encourage any systematic or general policy approach to sentencing which makes it difficult to provide a more general rationale for sentencing to the public. Decisions are made on a case-by-case basis and if necessary justified post hoc with an account which can include any philosophical justification or combination of justifications. From a cultural perspective, the definition of justice is controlled by the judiciary. The mode of accountability is the public trust in the office of the judge.

Thus, although sentencing is a collective social and cultural practice, the way in which decisions are justified and defended is located at the level of the individual judicial decision maker. The following section describes the cultural framework of sentencing. It shows how individualized sentencing, seen as an approach to making and justifying decisions about justice, promotes particular values, allocates the power to define what is to count as justice to particular agencies and processes, and adopts particular rhetorical devices to persuade audiences of its propriety and legitimacy.

Sentencing As The Performance Of Justice

Sentencing decisions perform justice. They define what counts as a “just” decision. These decisions also need to be justified. The discourse of individualized sentencing needs to explain how decisions are just and also needs to demonstrate that the process by which these decisions were reached was legitimate and persuade audiences of the propriety and correctness of this decision-making process. In this sense sentencing shares much in common with administrative decision making. Recent work in the cultural sociology of administrative justice provides a useful framework with which to analyze the ways in which sentencing seeks to construct just decisions and defend these decisions.

Sentencing is a legal decision in so far as decisions are made by judges, have the authority of the court, and are therefore legitimate. However, the way in which sentencing decisions are made accountable and justifiable has as much in common with administrative decision making as it does with judicial decision making. Although sentencing decisions are made by judges, the procedural form and mode of justification through which these decisions are made and defended are, in important ways, quite unlike other judicial decisions. Kagan (2010) argues that the characteristic function of an administrative decision is to get the work of society done while the characteristic function of a legal decision is to establish the legal coordinates of a situation in light of pre-established legal rules. In terms of Kagan’s typology, sentencing decisions look more like administrative decisions than legal decisions.

Individualized sentencing is more about doing the job of making a “just” decision in an individual case than it is about applying rules to facts. “Rules are based on generalisations” (Kagan 2010, p. 11). A rule says that if A and B and C obtain, then the appropriate decision is X because X will advance the policy goals of the organization. In the choice of a type and amount of sentence, there are no rules which specify that if circumstances A, B, and C exist, then the judge must pass amount Y of sanction X (with the exception of mandatory life sentences in some jurisdictions). For example, there might be a well-known customary practice whereby offenders convicted of injury with a weapon which causes permanent disfigurement will receive a prison sentence, but this is a custom not a rule. The judicial decision about the appropriate type and severity of sanction is not rule governed, and thus the accounts provided to justify these decisions cannot be rule based.

Administrative decision making requires the decision maker to respond to complex and rapidly changing social circumstances which are not susceptible to the generalizations applied in fixed legal rules. Administrative decision making requires experience, expertise, and specialization to enable outcomes to be adjusted to meet the peculiarities of each individual case. Judicial sentencing decision making is based on the exercise of discretion in individual cases to deal with complex and multiple facts and circumstances. It is in this sense that sentencing more resembles administrative decision making than legal decision making. This is not to argue that sentencing is an administrative decision but rather that the style of decision making employed and its modes of accountability have more in common with the processes commonly employed to defend “just” decisions in an administrative context. “Individualized sentencing” thus serves as an important means of justifying decisions but not necessarily as an accurate account of the empirical process of making decisions.

Mashaw has argued that administrative justice refers to

the qualities of a decision process that provide arguments for the acceptability of its decisions. (Mashaw 1983, p. 16)

Justice, in this context, is about the decision maker being able to provide an account of the decision process that enables the public to make a judgement about whether or not the decision is a fair and reasonable decision (Tata 2002). Members of the public may disagree with the substantive decision, but still be satisfied that it was reached by a fair and reasonable process. Individualized sentencing serves a similar purpose for sentencing. A “just” sentencing decision is reached by taking into account all of the facts and circumstances of the individual case and coming to a judgement about the type and level of sanction required.

Christopher Hood has produced a cultural analysis of administrative justice which is employed here to help understand how “individualized sentencing” defines and puts into practice a particular concept of “justice” and also to identify the challenges to this discourse based on an understanding of its weaknesses (Hood 1998).

Legitimacy And Accountability

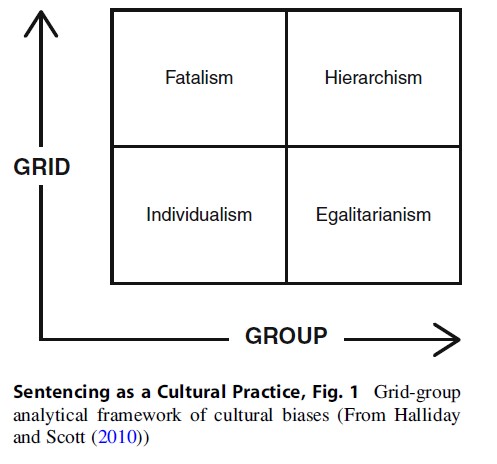

Mary Douglas famously proposed that social relations between individual actors and the institutional arrangements for managing these individuals could be classified along two variables which she called group and grid (Douglas 1982 quoted in Halliday and Scott 2010) (Fig. 1).

In the context of decision-making processes, grid refers to the level of externally imposed prescriptions experienced by a decision maker. High grid means the decision makers are relatively strictly bound by rules/prescriptions over which they have little or no control, and low grid means the opposite: that decisions makers have wide-ranging discretion and are relatively unconstrained by rules. Group refers to the extent to which individuals see themselves as being incorporated into bounded units, as sharing a sense of the collective. In terms of justice, a high-grid approach believes that “justice” is most effectively delivered through a closed and controlled process and a low-grid approach implies greater openness and flexibility. A high-group approach attempts to deliver collective values, a low-group approach prioritizes individual self-interest. Group addresses questions about political legitimacy, that is about who is authorized to make decisions. Grid addresses questions about modes of accountability, about what processes make decisions transparent. So this refers to how individuals both perceive their social world and how they are able or not able to understand, challenge, and participate in decision making. It refers to the relationship between the state and the individual, a fundamental concern of political theory and law.

Examining behavior across these two dimensions gives four ideal types which can be used to exhaustively classify decision-making processes: hierarchism (high grid high group), individualism (low group high grid), egalitarianism (high group low grid), and fatalism (low group low grid). These are normative ideal types which prioritize different values in decision making. Hierarchism emphasizes expertise and skills; egalitarianism emphasises citizen participation; individualism prioritises competition; and fatalism favours stoicism and/or serendipity. As with all ideal type analysis, these are highly unlikely to exist in their pure forms in the observable world. Rather, particular decision processes will exhibit varying degrees of some or indeed all of the types, usually one being predominant.

Individualized sentencing exhibits high-group features. Authority over sentencing decision making is shared between the legislature and the judiciary. The legislature set the legal framework which judges implement. Judges are entrusted to act on behalf of the collective. In practice, the legislature leave the judiciary with wide discretion to make sentencing decisions. Individualized sentencing provides a persuasive account of how just sentences are made in order to promote the collective good.

The issue of grid is more complex. At first sight, the relative paucity of rules might suggest that sentencing is low grid, but a closer examination of the discourse of individualized sentencing suggests that it is more accurately classified as high grid. The discourse of individualized sentencing effectively restricts access to decision making to the judiciary. Individualized sentencing presents itself as the single correct way to make just sentencing decisions, an approach which can only be implemented by judges and experts by virtue of their education, knowledge, and experience and which is thus inaccessible to ordinary members of the public. Sentencing decisions are justified on a case-by-case basis. There is no set of rules which can be applied to provide a justification for the sentence chosen in each case. Judges are expected and entrusted to exercise their skill and judgement for public benefit. Citizens are not expected to participate. Individualized sentencing may not have the transparency of a grid, but it has the rigidity and stability of a grid. Individualized sentencing is thus firmly a hierarchist form of decision making.

In an individualized sentencing regime, sentencing is controlled by the judiciary. Other agents and officials play a part in the decision-making process. Defense agents have the opportunity to make a plea in mitigation. Reports provided for the court by probation or social work staff provide an opportunity for these professional groups to contribute to the decision-making process. However, ultimately the decision is made by the judge. Sentencing is “owned” by the judiciary (Tata et al. 2008). Individualized sentencing is thus substantive rather than formal, irrational rather than rational, and hierarchical rather than participatory. Hierarchical, in so far as the judge controls the process and standards for decision making and yet informal in so far as the authority of the decision, rests with the power of the decision maker and not with detailed legal rules.

Challenges To Hierarchism In Sentencing

Egalitarianism

In most late modern societies, confidence in authorities and experts is diminishing (Garland 2001). The judiciary are no exception. Judges seem to be losing public trust and may no longer be able to rely on their education, status, and tradition to sustain public confidence (Hough and Roberts 2004). The perceived monopoly of the judiciary as the “owners” of sentencing is being challenged. Kagan (2010) argues that political leaders will be comfortable with an expert judgement system so long as the electorate displays high levels of trust in the experts. However, where there is evidence that trust is in decline, leaders are likely to seek to impose a more formal and legalistic decision system with clearer accountability.

There is evidence of an increasing desire amongst citizens to have a greater input into sentencing decision making. Single-interest groups in many jurisdictions particularly those representing victims of crime and their families seek to have a greater influence on sentencing decision making. Some US states have a strong populist tradition which enables more direct citizen involvement in sentencing (California’s public initiatives). A variety of sentencing institutions, usually known as councils or commissions, have been introduced in many common law jurisdictions (Hutton 2008). Some of these have the power to establish sentencing guidelines; others provide public information, education, and advice. Most of these institutions offer citizens an opportunity to influence sentencing decisions, but the discourse of individualized sentencing has proved highly resistant to change because of the powerful cultural messages that it communicates.

The history of the sentencing guidelines movement (Tonry 1996) is the story of attempts to provide a more structured approach to sentencing which allocates greater significance to the pursuit of consistency in sentencing rather than the delivery of a just sentence in each individual case. This also makes sentencing decision making more transparent and accountable and therefore more susceptible to rational debate. Individualized sentencing invites challenges about who makes sentencing and policy and what the aims for such a policy should be.

Individualism

It is hard to imagine sentencing being operated by the market, although there is increasing private sector involvement in the administration of punishment. However, it is not so hard to imagine a market approach being used to assess sentencing. In most areas of government spending such as health or education, the executive is responsible and accountable for setting budget priorities for the expenditure of public funds to manage activities in these areas. Ministers are responsible for ensuring that their officials make their decisions in a just manner, ensuring, for example, that appropriate processes have been observed and that the decisions are fair and reasonable. In common law jurisdictions where there are no comprehensive sentencing guidelines, the aggregate of sentencing decisions is, de facto, the sentencing policy for these jurisdictions. In this sense sentencing may be seen as a decision-making process which effectively allocates scarce penal resources in a particular way and provides a form of public justification for these decisions.

In an individualized sentencing approach, justice is defined with reference to an individual case and wider policy considerations about how sanctions might be allocated in a more cost-effective manner are not relevant. Decisions about justice are made by judges not policy makers although the allocation decisions of judges have significant public policy impact. Many US states are seeking to exert greater regulatory control over judicial decision making in sentencing to enable the government to exercise greater control over penal expenditure (National Conference of State Legislatures 2011). These pressures are being felt across Western jurisdictions. Politicians are keenly aware that justice clearly has a price and that for many jurisdictions, the current price is no longer affordable.

Fatalism

Fatalism is the belief that decision making is an unpredictable lottery. It can lead to cynicism and populist anger or it can lead to quietism and tolerance. There is also a strong element of fatalism in so far as citizens feel unable to influence sentencing policy and practice which is widely perceived to belong to the judiciary rather than the province of elected governments.

The strength of fatalism as a cultural bias should not be underestimated. It almost goes without saying that governments and judges need to see themselves as making positive and constructive decisions, as both being able to and having a duty to “make a difference.” At the same time individuals judges, ministers, and policy makers will from time to time feel that their job is impossible. Crime will never go away and it is hard to find evidence of effective ways of dealing with crime. The media hold politicians responsible and it is not hard for them to find instances of failure. This is a cultural perspective, not an objective fact. The inevitability of crime and the apparent limitations of punishment to control crime need not lead to despair or cynicism, but rather to different ways of defining the issue and different modes of action to develop higher-group identification.

From a cultural perspective, decisions about justice in sentencing are justified by a hierarchist approach which is based on public trust in the discretionary decision making of individual judges on a case-by-case basis. This approach prioritizes particular values, most significantly those of professional expertise and experience and intuitive moral judgement. The inherent weaknesses in this approach are challenged by approaches which want to give a higher priority to different values, for example, a more rational and transparent form of accountability and a greater involvement of citizens and interest groups in decision making.

Conclusion: Why Is The Cultural Analysis Of Sentencing Decision Making Useful?

Cultural analysis is useful to examine both stability and change in sentencing. In cultural terms, individualized sentencing has proved exceedingly durable and resistant to criticism. The discourse allows judges to retain control over the ways in which sentencing decisions are made and, perhaps more significantly, over how decision making is justified. The idea of fitting a sentence to the particularities of each individual case is fundamental to common sense conceptions of justice, and individualized sentencing deploys classic rhetorical devices to persuade audiences that it is the only process which can guarantee the production of justice in sentencing. To that end, justice is held to depend on scrupulous consideration of the detailed facts and circumstances of each case. The decision is made by judges and members of a respected, principled, and almost sacred profession, located above the compromised, pragmatic, world of politics. Their method is archaic, mysterious, and sacerdotal. Concerns about consistency, accountability, and rationality are presented as misguided attempts to objectify something which is inherently subjective. This representation of sentencing chimes with our common sense understandings of crime as a matter of individual responsibility, attributable to bad moral decisions made by individual offenders. It reflects the narratives of crime and punishment that form the basis of crime fiction, television crime drama, and Hollywood movies. At least part of the explanation for the resilience of individualized sentencing as an approach to sentencing lies in its insistence that “just” punishment is about the right punishment for an individual offender.

At the same time, like all justice discourses, the discourse of individualized sentencing contains the seeds of its own potential demise. As its strength is dependent on public trust in the judiciary, so it is vulnerable as this trust is perceived to be waning. Hood (1998) argues that cultural change always emerges from the perceived weaknesses of an existing state of affairs as opposed to being driven by utopian theoretical proposals premised on the possibility of starting with a blank sheet of paper. A cultural understanding tells us that any approach to decision making has both strengths and weaknesses. Change often results from the perceived failure of a process being attributed to its inherent weaknesses and solutions being sought in processes which exhibit strengths in these areas. Thus, the “problem” with individualized sentencing is its lack of transparency and limited capacity to hold judges accountable for their decisions, just as the problem with systems of sentencing guidelines is their perceived inability to take proper account of the distinctiveness of each individual case (Aas 2005).

A cultural analysis allows a better understanding of the traditional common law approach to sentencing. It shows that individualized sentencing is a political choice, not an inevitability, and that it is susceptible to challenge by approaches which offer a different version of what it means to produce justice in sentencing, for example, approaches which give a higher priority to consistency, accountability or effectiveness, and value for money. It shows that the approach to sentencing decision making in a jurisdiction arises out of political contest between politicians, administrators, judicial officers, third sector organizations, and other groups, all of which is conducted in a particular time and place and which is represented in various forms of media. It shows that there is no single objective definition of justice but rather a range of definitions over which there is continual contest.

Bibliography:

- Aas KF (2005) Sentencing in the age of information: from Faust to MacIntosh. Glasshouse Press, London

- Ashworth A (2010) Sentencing and criminal justice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Bourdieu P (1977) Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Castellano U (2009) Beyond the courtroom workgroup: case workers as the new satellite of social control. Law and Policy 31(4):429–462

- Douglas M (1966) Purity and danger. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Douglas M (1982) Introduction to group -grid analysis. In: Douglas M (ed) Essays in the sociology of perception. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Garland D (2001) The culture of control. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Garland D (2006) Concepts of culture in the sociology of punishment. Theor Criminol 10(4):419–447

- Halliday S, Scott C (2010) A cultural analysis of administrative justice. In: Adler M (ed) Administrative justice in context. Hart Publishing, Oxford

- Honderich T (1989) Punishment: the supposed justifications. Polity Press, Cambridge

- Hood C (1998) The art of the state: culture, rhetoric and public management. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Hough M, Roberts JV (2004) Public confidence in criminal justice: an international review. King’s College, Institute for Criminal Policy Research, London

- Hutton N (1995) Sentencing, rationality and computer technology. J Law Soc 22(4):549–570

- Hutton N (2006) Sentencing as a social practice. In: Armstrong S, McAra L (eds) Perspectives on punishment: the contours of control. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- McNeill F, Burns N, Halliday S, Hutton N, Tata C (2009) Risk, responsibility and reconfiguration: penal adaptation and misadaptation. Punishment Soc 11(4):419–442

- National Conference of State Legislatures (2011) Principles of effective state sentencing and corrections policy. NCSL, Washington, DC. www.ncsl.org

- Hutton N (2008) Institutional mechanisms for incorporating the public in the development of sentencing policy. In: Freiberg A, Gelb K (eds) Penal populism: sentencing councils and sentencing policy. Willan Publishing UK/Federation Press, Australia

- Kagan RA (2010) The organisation of administrative justice systems: the role of mistrust. In: Adler M (ed) Administrative justice in context. Hart Publishing, Oxford

- Latour B (2005) Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor network theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Mashaw J (1983) Bureaucratic justice: managing social security disability claims. Yale University Press, Newhaven

- O’Malley P (2009) The currency of justice: fines and damages in consumer societies. Routledge Cavendish, London

- Padfield N (2011) Time to bury the custody “threshold”? Crim Law Rev 8:593–612

- Reitz K (2005) The enforceability of sentencing guidelines. Stanford Law Rev 58(1):155–173

- Smith P (2008) Punishment and Culture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Sudnow D (1965) Normal crimes: sociological features of the penal code in the public defenders office. Soc Probl 12(3):255–276

- Tata C (2002) Accountability for the sentencing decision process : towards a new understanding. In: Hutton N, Tata C (eds) Sentencing and society. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp 399–420

- Tata C (2007) Sentencing as craftwork and the binary epistemologies of the discretionary decision process. Soc Leg Stud 16(3):425–447

- Tata C, Burns N, Halliday S, Hutton N, McNeill F (2008) Assisting and advising the sentencing decision process: the pursuit of ‘quality’ in pre-sentence reports. Br J Criminol 48(6):835

- Tombs J (2004) A unique punishment? Scottish Consortium Crimed Criminal Justice. http://www.scccj.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2011/08/A-Unique-Punishment.pdf

- Tonry M (1996) Sentencing matters. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Yanow D (1996) How does a policy mean? Interpreting policy and organisational actions. Georgetown University Press, Georgetown

- Yngvesson B (1989) Inventing law in local settings: rethinking popular legal culture. Yale Law J 98(8):1689–1709, 6224 words August 2012

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.