This sample Sexual Recidivism Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Sexual recidivism is concerned with the reoffending of sexual offenders who have already had contact with the criminal justice system. This research paper emphasizes the need to carefully define what is meant by recidivism and discusses some of the pitfalls in this area. It then focuses on recidivism rates, following on with a consideration of risk factors for recidivism, both static and dynamic, before commonly used risk scores are introduced. A discussion on specialization and glances towards possible developments in this area concludes the section.

Fundamentals

This research paper is concerned with sexual recidivism, that is, the “persistence” of sexual offending once an offender has been arrested or convicted and addresses the future risks posed to the public by sex offenders after conviction.

Defining Recidivism

To begin, definitional aspects of recidivism and its measurement are considered, including the outcome measure, the type of recidivism, the time horizon, and the definition of what constitutes a sexual offense.

Recidivism: Recidivism is defined as the reoffending of a known offender; however, Falshaw et al. (2003) have noted that “there is little consistency in the way this term is used and the specific behaviour it refers to.” They remind the reader that Maltz, in his classic book on recidivism, pointed to the use of nine different indicators of recidivism across a total of 90 studies in the United States, i.e., absconding, arrest, incarceration, parole violation, parole suspension, parole revocation, reoffense, reconviction, and probation violation.

Focusing explicitly on sexual recidivism, Falshaw et al. (2003) distinguished between sexual reconviction, sexual reoffending, and sexual recidivism. Their view was that recidivism is primarily concerned with lapsing into previous patterns of behavior and thus encompassed other forms of potential sexual-offense-related behavior such as loitering outside a school. They defined sexual reconviction as a subsequent conviction for a sexual offense, sexual reoffending as the perpetration of another illegal sexual act (whether caught or not), and sexual recidivism as the commission of a behavior related to a sexual offense, legal or illegal, with a clear sexual motivation. A more common use of the term sexual recidivism in the literature and one which is used in this research paper, however, is some kind of official contact with the criminal justice system for a sexual offense, whether it be arrest, charge, or reconviction.

There is an implicit hierarchy within these distinctions. A “sexual reconviction” is the strictest measure as, to count, one needs the endorsement of a court of law. “Sexual recidivism” is a broader measure and may include arrests or charges as well as convictions for a sexual offense. “Sexual offending” has difficult counting and legal implications as it includes illegal sexual acts, whether caught or not. It is crucial to understand the importance of such analytical distinctions as the use of different outcome measures can produce very different results.

Type of Recidivism: Many studies on the recidivism of sexual offenders use as their outcome measure any form of recidivism – a general measure of subsequent contact with the criminal justice system for any offense. Others are interested in whether sexual recidivism has taken place, whereas yet others are concerned with recidivism for dangerous offenses which is usually taken to be sexual or violent recidivism.

Time Horizon for Follow-Up: Some studies have a fixed time horizon or a fixed series of time gates whereby recidivism rates, say, 5 or 10 years after release can be established. Other studies use an average follow-up time – these are less valuable as their results cannot be generalized in systematic reviews.

Nature of the Sample Taken: Some recidivism studies relate to those incarcerated in prison or in a treatment facility; others involve those with community sentences as well. Other aspects are also important – are females as well as males included, and is the sample restricted to a particular age range? Specifically, are juvenile offenders included?

Definition of a Sexual Offense: Normally, legal statutes which categorize sexual offenses (e.g., rape, indecent assault, exhibitionism) are used, but these can differ from country to country and from US state to US state. Most of these differences currently relate to laws against consensual homosexual activity (e.g., Malaysia, Zimbabwe). In addition, the age of sexual consent varies from country to country, varying from 12 (e.g., parts of Mexico) to 20 (Tunisia), and in some countries sexual behavior outside marriage is illegal (e.g., Saudi Arabia, UAE). The age of consent also varies from state to state in the USA and in Australia. There is a further issue relating to long-term or historical recidivism studies in that the definition of what is a sexual offense will change over time. A specific example relates to the laws of sodomy, or “unnatural” sex, which was in effect a legal prohibition in 14 US states until 2003. This makes comparison of recidivism rates across time, across countries, and across states problematic.

There are two further issues relating to whether an offense can be classified as sexual. Some offenses may be classified as a sexual offense but may indeed have no sexual motivation. For example, some might regard “bigamy,” which until recently was classified by the Home Office as a sexual offense in England and Wales, as more of a deception than a sexual offense. In contrast, other offenses captured under “theft” (e.g., stealing underwear) could be regarded as more indicative of a sexual than acquisitive motivation but are unlikely to be included. Less well recognized is the fact that most reconviction studies are based on the principal offense committed. Hence, someone convicted of both murder and rape, for example, is recorded for murder as the principal offense, while the offense of rape is masked.

Risk and Prediction: A risk is a chance or probability that some event (usually undesirable) will happen in the future. Thus, one can talk about the risk of a sexual offender being reconvicted for a sexual offense in the next 5 years on release from an English prison. Good risk statements should include some element of location (risks for offenders in the Netherlands may well be lower than in the UK) and some indication of a future time horizon (the next year, the next 10 years, etc.) – however, these are sometimes left implicit, leaving the reader to judge what the statement means. A prediction usually relates to a particular person and uses the risk measure to make a judgment about an individual. This prediction may, in turn, be acted upon and some judgment made about the individual based on the prediction. Mostly, the assessment of risk in criminology is about potential dangerousness.

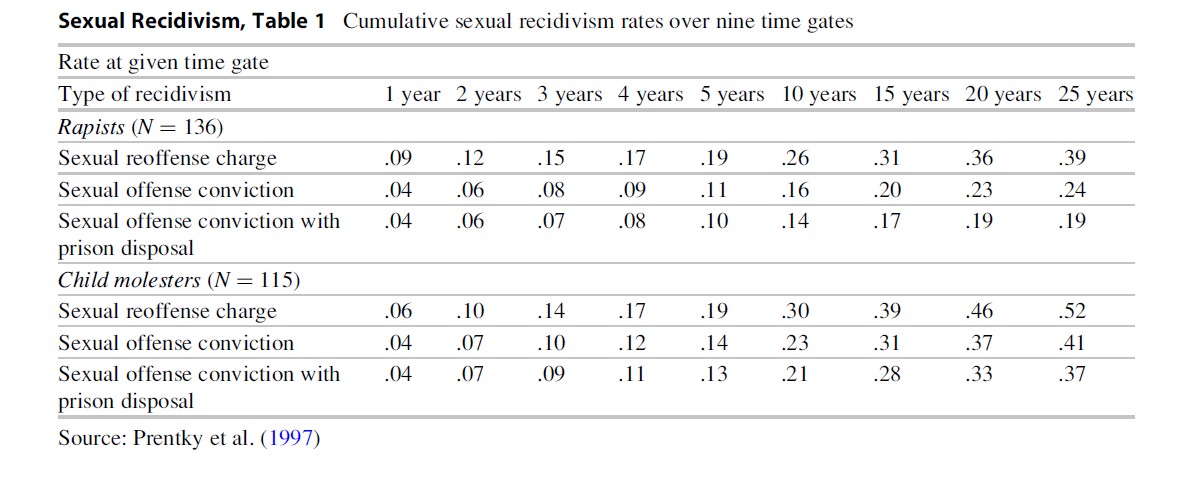

The Risk Of Sexual And General Recidivism

Both large numbers and a long-term follow-up are thought to be crucial in the quest for a definitive study about recidivism rates. Although systematic reviews suggest that the observed sexual recidivism rates are only 10–15 % after 5 years (Hanson and Bussie`re 1998), the rates continue to increase gradually with extended follow-up periods. The study by Prentky et al. (1997), using a follow-up to 25 years from a treatment center in Massachusetts, demonstrated that, if they had restricted the follow-up to less than 24 months, they would have missed up to 45 % of new charges. While even with a 5-year follow-up period, they would still miss 30 % of the charges they finally identified. In fact, they examined the cumulative failure rates for new charges for sexual offenses only as well as for new charges of any offense. They used nine time gates, broken down by charge, conviction, and imprisonment. Table 1 shows the recidivism rate for new sexual charges.

As Table 1 shows, the conviction rates after 2, 5, 10, and 25 years were 6 %, 11 %, 16 %, and 24 % for rapists, while the comparable figures for child molesters were 7 %, 14 %, 23 %, and 41 %. The work of Prentky and his colleagues provides a very clear case in demonstrating the importance of long-term follow-ups.

More recently, the results of Prentky et al. (1997) have been validated by Cann et al. (2004), who followed up all 419 male sexual offenders discharged from prison in 1979 in England and Wales until 2000, giving a followup period of 21 years. The sexual reconviction rates after 2, 5, 10, and 20 years were 10 %,16 %, 20 %, and 25 %; the equivalent figures for general reconviction were 34 %, 49 %, 56 %, and 62 %. The sexual conviction rates are higher at the 2year point than either of Prentky et al.’s subsamples, but after that point, the reconviction rates are very similar.

Risk Factors And Sexual Recidivism

As already stated, the risk of recidivism is the probability or chance that the offender, who has already offended once, will take place again in the future within some time horizon. The risk will depend on characteristics of the offender, and it is therefore important to identify a set of factors or variables which are known to be associated with the risk of recidivism. Five such factors are highlighted below.

Sexual Recidivism And Gender

The extent of female sex recidivism is still under-researched; however, differences between male and female sexual offenders in terms of recidivism have been observed. Freeman and Sandler (2008) took a matched series of 780 female and male sex offenders in New York State and demonstrated that male sex offenders were significantly more likely than female sex offenders to be rearrested for both sexual and nonsexual offenses. A later study by the same authors (Sandler and Freeman 2009) extended this work and took 1,466 female offenders who were then followed up for 5 years. The 5-year rear-rest rate for these offenders was a very low 1.8 % for a sexual offense and 26.6 % for any offense. Cortoni et al. (2010) concurred with the general conclusion of low rates for female sexual recidivism and, in a meta-analysis using 10 studies, found that the rates were typically under 3 % with an average follow-up of six and a half years.

Sexual Recidivism And Age

The age variable is also theoretically very relevant, particularly in relation to developmental psychology. For instance, Hanson (2002) identifies three broad factors relevant to sexual offending – deviant sexual interests (motivation), opportunity, and low self-control – and uses these to help explain the variation in the recidivism rates of various offenses. So, he maintains that, for rapists, all three factors should decline with age – “self-control should increase in young adulthood, deviant sexual drives should decrease in late adulthood, and opportunities should gradually decline throughout the life span” (Hanson 2002). Consequently, Hanson is not surprised that most rapists are young and that their recidivism rate steadily decreases with age. In contrast, in explaining that child molesters are generally older than rapists, he points to competing factors influencing recidivism risk during early to middle adulthood with, for instance, self-control probably improving but the opportunities for child molesting may well be increasing.

Thornton (2006) has noted that “sexual offenders released at a younger age tended to be more general criminals while those released at an older age tended to be sexual specialists.” But Barbaree et al. (2003), focusing more specifically on sexual recidivism, produce an extra twist. They argue that “if libido [seen as one of the important determinants of sexual aggression] decreases with aging, then it follows that sexual aggression should show similar aging effects.” Certainly their results suggested that “offenders released at an older age were less likely to recommit sexual offences and that sexual recidivism decreased as a linear function of age-at-release” (Barbaree et al. 2003).

Following reviews and meta-analyses, the consensus is that there is an inverse relationship between sexual offenders’ age at the time of their release from incarceration and their sexual recidivism risk (Thornton 2006; Hanson 2002; Hanson and Bussie`re 1998). However, Doren (2006) notes some recent challenges to this “iron law” – Doren found a series of “study-specific conclusions … that were often mutually exclusive.” Reanalysis of existing data showed numerous potential interacting variables, such as participation in treatment, type of risk measure used, type of sexual offender, jurisdiction, and even a different measure of offender age. In other words, to explain the wide disparity of findings among the studies he reviewed, there were perhaps confounding variables in all of the reviewed research. While the age variable is definitely on the agenda, Doren concludes that “we have a lot of work to do before we can say we understand how to consider offender age in sexual recidivism assessments” (p. 156).

Sexual Recidivism Of Juveniles

In law and policy, the age divide between juveniles and adults is particularly crucial. However, the activity of juvenile sex offending has only comparatively recently attracted attention and research interest. In fact, over the past decade or so, sexually abusive juveniles/adolescents have increasingly been distinguished from adult offending. Worling and La˚ngstro¨ m (2003) provide a useful and detailed review of studies indicating criminal recidivism risk with adolescents who have offended sexually. They identify, for example, that their own study on 117 sexual adolescents reported a 30 % sexual reconviction rate after a mean follow-up of 9.5 years. Such rates are higher than the Prentky et al.’s 10-year reconviction rates reported earlier in this research paper.

An important counterweight to the concern that juvenile sex offenders are likely to be particularly dangerous is provided by Caldwell (2007). Caldwell compared 249 juvenile sex offenders and 1,780 nonsexual offending delinquents who were released from secured custody and contrasted the sexual charge recidivism figures for juvenile sexual offenders and nonsexual offenders and found nonsignificant differences – 6.8 % compared to 5.7 % after a 5-year follow-up. This result has important implications for policy concerns. Quite simply, most juvenile sex offenders may not be the future threat that many might have expected.

The low rates of sexual recidivism among juveniles and adolescents are certainly noteworthy. Vandiver (2006) confirms how nonsexual offenses predominate in recidivism among juvenile sex offenders. Vandiver focuses on 300 registered male sex offenders who were juveniles at the time of their initial arrest for a sex offense. The series is followed through for 3–6 years after they reached adulthood, and while more than half of the series is arrested at least once for a nonsexual offense during this adult period, only 13 (or 4 %) were rearrested for a sex offense. Similar results are portrayed in Nisbet et al. (2004) showing relatively low rates of detected adult sexual recidivism but high rates of detected nonsexual recidivism, among young men who committed sexual offenses as adolescents. Hence, one is identifying relatively stable patterns of general antisocial conduct in adolescent sex offenders, but continuing aberrant sexual behavior is not much in evidence. Curiously, with this study, while age at assessment was found to predict sexual recidivism, rather counter-intuitively, it was an older age at assessment that predicted adult sexual offense charges. In fact, “the likelihood of being charged with sexual offences as an adult increased by 60 % with each year increase in age at assessment” (p. 230). This is an important finding as it confirms that very early sexual crime is generally unlikely to be a precursor to persistent sexual offending in adult life.

Sexual Recidivism And Type Of Sexual Offending

In general, large numbers of sex offenders are needed when testing the notion that different types of sex offenders have different kinds of outcome. Earlier work such as Prentky et al. (1997) had already hinted that some types of sex offenders were more likely to commit new sexual crimes than others, suggesting that child molesters have a substantially higher sexual recidivism rate compared to rapists. Other authors have disagreed with this conclusion. For example, Serin et al. (2001) have indicated that recidivism rates are higher for rapists than child molesters. Hanson (2002) notes that “rapists were younger than child molesters, and the recidivism risk of rapists steadily decreased with age.” Also differences in recidivism within the same kind of sex offense have been noted – for example, pedophiliac versus non-pedophiliac child molesters.

Sexual Recidivism And Prior Criminal History

The final risk factor highlighted is that of the offender’s prior criminal history. There are many ways of summarizing such information, but interest has been focused on the number of prior convictions, the number of prior sexual convictions, the age of criminal career onset, and the relationship between the victim and the offender of prior sexual offending. In general, such measures have been incorporated into risk scores, and criminal history is discussed more fully below.

Risk Scores And Sexual Recidivism

A sexual recidivism risk score, put simply, identifies the risk of future recidivism of a sex offender based on a set of risk factors. For example, the risk score might classify a typical offender with a set of characteristics into one of five categories – highly unlikely to reoffend, unlikely to reoffend, equally likely to reoffend or not, likely to reoffend, and highly likely to reoffend. A prediction of recidivism, in contrast, is using that risk probability or score (and possibly other information) to make a judgment as to whether one particular person will reoffend. Less commonly, a prediction might estimate how many of a group of offenders will reoffend. Thus, a prediction might be made that a male sex offender in California released from prison who has three prior sexual convictions has a 40 % chance of reoffending with another sexual offense in the next 5 years. Based on this prediction, a decision might be made on the form of post-release supervision needed by the offender.

Actuarial And Clinical Assessment Tools

There are two methods of assessing the risk of an individual for subsequent sexual recidivism. Actuarial measures use summary measures of criminal career data on a large set of offenders together with other information about the age, gender, and circumstance of the offender to estimate a risk score. The offenders are followed up for the required period of time, and each offender is then identified as a recidivist or not. This risk score estimate is made though the application of statistical modeling methods such as logistic regression or other score-building models. The performance of the measure can be assessed by dividing the set of offenders into two – using one part of the data to build the risk score and the second part to assess how well the measure performs.

Clinical risk assessment, on the other hand, takes the judgment of professionals such as psychiatrists, probation officers, or parole board members to make a relatively informal judgment on the likelihood of an offender to reoffend. Tools such as the Violence Risk Score for Sexual Offenders can be used to guide the judgment. Although these professionals will have access to the same information on past criminal career history, they will also take into account a whole set of personal factors such as degree of remorse, demeanor, family support, stable residential status, etc., to determine risk (Milner and Campbell 1995).

Both measures would tend to be used at the start of some process – for example, in presentence reports presented to the court or in considering release from an indeterminate prison sentence. Which of these two approaches appears to give better predictions? An important study by Grove and Meehl took 136 separate studies – a mix of clinical and actuarial studies. In general, the clinical studies had a great deal of extra information available compared to the actuarial studies (Grove and Meehl 1996). Their study came to two important conclusions. Firstly, in studies which compared practitioners, there was little agreement between them. Secondly, despite using less information, the actuarial studies were either equal or superior to clinical risk assessment.

However, there have been criticisms of the actuarial approach (Quinsey et al. 1995). Firstly, it can categorize whole groups of individuals as high risk – even though it is recognized that personal circumstances will mean that some individuals are at low risk within a high-risk group. Furthermore, actuarial measures fail to take account of factors such as the intention of the offender to desist from crime. There are also other criminological arguments which need to be considered – that actuarial risk measures focus on the individual to the exclusion of other causes of crime, notably economic and social deprivation. Nevertheless, actuarial measures are perceived by many as providing a reliable estimate of risk and are increasingly used in daily criminal justice practice. For dangerous offenders, current practice relies increasingly on some combination of a structured clinical judgment and actuarial measures.

“Static” Versus “Dynamic” Factors

The main focus in predicting recidivism risk from its outset has been on historical, or “static,” factors. These are factors relating to the prior criminal history of the offender such as age of first conviction; the number of previous sexual and nonsexual convictions; demographic factors, such as age and gender; historical factors in the early life of the offender such as whether both parents were present when the offender was a child; as well as victim characteristics (stranger, familial) and type of offending (child molestation, rape, etc.). Age is regarded as a “static” factor as it is taken at some fixed point in time, such as conviction or date of release from prison or treatment center. As such factors are “static,” it is not possible to intervene and to change these to improve outcome.

Dynamic factors, in contrast, are subject to intervention. They can be divided into stable dynamic factors, which change slowly over time (such as job responsibility and attitudes to the opposite sex), and acute dynamic factors, which can vary day by day or hour by hour (such as day to day drinking behavior).

Building Risk Scores

Many risk scores in common use will apply statistical techniques to build a recidivism risk score. Data on a cohort of sex offenders is collected and each offender in the sample is followed up for a fixed period of time – typically 2 or 5 years – although longer follow-up periods can also be used. Typically, official data is used to assess whether the offender has recidivated by looking at arrest or court conviction records. Information on offender characteristics is also collected. These can be obtained from the criminal history of case notes of the offender. For scores involving dynamic factors, in addition, psychometric tests (e.g., for psychopathy) may need to be administered as they often contribute to the recidivism test score. Typically, logistic regression is then used to build a score and to determine the important risk factors. If follow-up times vary, then Cox regression may be used.

Once the score is built, its performance on new samples of offenders is assessed. Performance is usually measured by estimating the receiver operating characteristic curve of the score and calculating the AUC (area under the curve) which is expressed as a proportion or percentage. The AUC can be interpreted as follows: if two offenders are taken at random – one reconvicted and one not reconvicted – then the AUC gives the probability that the reconvicted offender will have a higher risk score than the unconvicted offender. Most risk scores used in assessing sexual recidivism have AUCs of around 0.70 or 70 %.

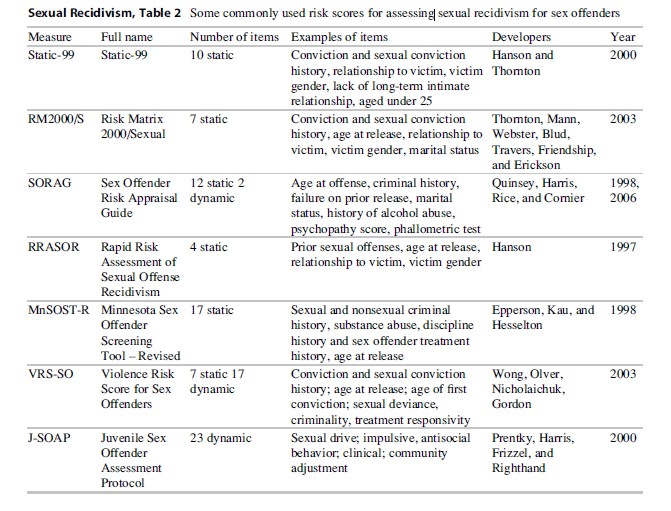

Risk Scores For Sexual Recidivism

Table 2 presents the sexual recidivism risk scores in common use, together with typical items which make up the score. As can be seen, four of the seven scores presented consist solely of static items, and only three scores attempt in addition to include dynamic factors.

Three measures are highlighted: the Risk Matrix 2000/Sexual (RM2000/S), the Rapid Risk Assessment of Sexual Offense Recidivism (RRASOR), and the Violence Risk Score for Sexual Offenders (VRS-SO).

The RM2000/S score consists of seven static items which relate to previous criminal history (number of previous court appearances, number of previous court appearances for sexual offenses, any conviction for a sexual offense against a male and against a stranger, any conviction for a noncontact sexual offense) together with measures of age at assessment and marital status. The test yields four risk categories – very high, high, medium, and low. The score is easy to administer and is used extensively by the UK Prison Service. AUC values of 0.75–0.77 have been reported.

RRASOR is an even briefer score and consists solely of four items and is, as its name suggests, easy to administer. The items are the number of prior sexual offenses, age of offender, gender of victim, and relationship to victim. AUC values of between 0.65 and 0.79 have been reported by various authors.

More recently, risk scores involving both static and dynamic factors have started to be introduced. The VRS-SO is one example of this development. The score includes both static items (conviction and sexual conviction history, age at release, age of first conviction) and a range of 17 dynamic items (sexual deviant lifestyle, sexual compulsivity, interpersonal aggression, and cognitive distortions are four of the items). The 17 dynamic items represent three underlying components of sexual deviancy, criminality, and treatment responsivity, together with additional items for intimacy deficits and emotional control. Theoretically, it uses “stages of change” to assess sexual-offending-related attitudes and behaviors and is administered twice, for example, pretreatment and post-treatment. The VRS-SO developers highlight its sensitivity to treatment-related change as well as to other forms of intervention. In terms of predictive validity at the time of development, AUC values ranged from 0.66 to 0.74. Beggs and Grace (2010) recently assessed the score and reported an AUC of 0.80 and also stated that the dynamic items provided additional predictive power after controlling for the static items. However, it needs to be stressed that researchers need training in the use of the instrument and the administration of the instrument is lengthy.

Researchers are divided about the utility of including dynamic measures in a risk score. The developers of VRS-SO argue that dynamic variables do not necessarily have to add to the predictive efficacy of static variables to be useful, stressing that their utility in treatment and in assessing risk change is also important.

Another area of controversy is whether age needs to be included in a risk score which includes dynamic items. The argument is that as most databases used to construct tests are cross-sectional, then age differences in the sample may represent birth cohort effects as well as age, and the distinct contribution of age cannot be determined (Harris and Rice 2007). An additional concern is that the dynamic items include measures of self-control, antisocial traits, and sexual potency, which will decline with age; hence, the inclusion of age in addition to these trait measures will over-predict sexual recidivism. However, Barbaree et al. (2009) have determined that age provides additional explanatory power over antisocial and sexual deviance measures in assessing recidivism.

In general, the choice of score depends on whether assessors have the skill, training, and time to assess offenders on the dynamic items. Scores involving dynamic items are best suited to those offenders who are incarcerated where there may be an interest in possible change, while court-based assessment is probably carried out more efficiently by using a static measure.

Recidivism And Specialization

A separate but related debate to sexual recidivism is that of specialization, which is defined as the tendency to commit the same type of offense. Specialist sexual offenders therefore have a tendency to recidivate with another sexual offense to a greater extent than the average offender.

Lussier (2005) explains that two major hypotheses have been put forward to describe the criminal activity of sexual offenders in adulthood. The first of these states that sexual offenders are specialists who tend to repeat sexual crimes. The second describes sexual offenders as generalists who are versatile in their offending. He goes on to state that the current state of knowledge provides empirical support for both the specialization and the generality hypothesis. A recent study has examined the specialization of sexual offenders both pre-and post-commitment (Harris et al. 2011). They found strong evidence of versatility but also found that those offenders who specialized prerelease were more likely than versatile offenders to specialize in sexual offending on release. They also found that child molesters were more likely to specialize than rapists or incest offenders.

The results suggest that sexual offenders are both versatile and specialist – a hypothesis originally suggested by Soothill et al. (2000). This study compared the criminal records of the 6,097 males convicted in 1973 in England and Wales of one of four offense categories – indecent assault against a female, indecent assault against a male, indecency between males, and unlawful sexual intercourse (USI) with a girl under 13 – over a 32-year observation period looking backward 10 years and forward 22 years, and very different patterns emerged for the four groups (Soothill et al. 2000). It showed that each offense group had very different criminality patterns in terms of their likelihood of being convicted of any (general) offense on another occasion – ranging from 37 % of those convicted of indecency between males to 76 % for those convicted of USI under 16. These sex offenders were shown to differ greatly in terms of general offending behavior – a higher proportion of those committing heterosexual offenses (i.e., indecent assault on female or USI with a girl under 16) tend to be convicted for violence against the person, property offenses, and criminal damage compared with the other two groups; however, a lower proportion of these offenders commit sexual offenses on other occasions. In contrast, those committing homosexual offenses (i.e., indecent assault on a male or indecency between males) are the mirror image. They are much less likely, compared with other sex offenders, to be convicted of violence or property offenses, while those committing indecent assault on a male are much more likely to be convicted of sexual offenses on other occasions.

At one level, therefore, sexual offenders may or may not specialize within their general criminal career, while at a more specific level offenders may or may not specialize in specific kinds of sex offending within their sexual criminal career. These two levels may act quite independently insofar that an offender could be a specialist at one level and a generalist at another. Miethe et al. (2006) have confirmed this picture by identifying, within low levels of general specialization, that 37 % of serial child molesters and 27 % of serial rapists were identified as specialists, offending with their specific types of sexual crime in the early middle and late third of their criminal careers.

Future Directions In Risk And Sexual Recidivism

This research paper concludes with an indication of possible future directions in the study of sexual recidivism, focusing on new data sources, improvements in the methodology of risk score building, and better understanding of the criminal careers of sex offenders.

New Data Sources: One major difficulty with the construction of risk scores is that, in general, they are both constructed and validated on data sets containing a relatively small number of cases. Risk scores are, moreover, often built on specific samples such as sexual offenders in prison. However, the potential is there to construct longitudinal data sets through record linkage which would take complete birth cohorts of sex offenders and follow them up in terms of their conviction or arrest records for long periods of time. For example, one potential source for such data would be the population registers of the Scandinavian countries, which, when linked together, would provide information on police contacts, convictions, employment, income, and demographic variables.

New Methodologies for Assessing Recidivism: Improved data sets will allow more sophistication in the type of models which can be built to explain recidivism. Firstly, new forms of dynamic factors can be introduced. Marital status, for example, is currently included as a static variable, but having dynamic information on changes of marital status, as well as changes in job status and responsibility for children, will provide additional explanatory power which may prove useful. Modeling techniques such as the Cox discrete-time model can help to build prediction scores with time-varying covariates. Secondly, group-based trajectory modeling, which has proved its worth in identifying latent trajectories of offending frequency over the criminal history, and group membership of such classes is starting to be used as a predictor for future recidivism (Lussier et al. 2010). Thirdly, new methods of prediction from the machine-learning and data-mining disciplines (neural networks, support vector machines, random forests) will offer additional sophistication which can deal with the inherent nonlinearity of covariates on recidivism outcome.

Specialization and Recidivism: Most work on specialization and sexual offending has dealt with the whole of the criminal career. However, alternative methods are now available which propose that offenders may favor certain offense types during the short term, largely because of opportunity structures, but that because of changing situations and contexts over the life course, their offending profiles aggregate to versatility over their criminal career as a whole. This notion has not been considered specifically for sex offending. However, it seems possible that offenders may well have particular sex crime preferences in relatively narrow time periods and then transition to other kinds of behavior over time.

Reintegration into the Community: Recently, work has been carried out on how long after sentence or release general offenders become similar to non-offenders in their propensity to commit crime (e.g., Bushway et al. 2011). This idea of redemption and reintegration is important as it can help to determine policy such as how long DNA samples or old criminal records are kept for. This work needs to be extended into sexual offending, and the risk or hazard of future offending for different lengths of arrest or conviction-free periods needs to be determined and compared with non-offenders. Such results should inform the length of time sexual offenders are placed on sex offender registers.

Apart from these specific developments, it is important to realize that societal factors as well as personal and individual factors will affect sexual offending and recidivism. Indeed, it can be argued that changes in society rather than individual upbringing and attitudes have affected the long-term trends in sexual offending and changes in rates of recidivism. The focus of research into sexual recidivism in the last 20 years has focused on the individual; the next 20 years needs to focus more on society and community effects.

Bibliography:

- Barbaree HE, Blanchard R, Langton CM (2003) The development of sexual aggression through the life span: the effect of age on sexual arousal and recidivism among sex offenders. In: Prentky RA, Janus ES, Seto MC (eds) Sexually coercive behavior: understanding and management, vol 989. New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp 59–71

- Barbaree HE, Langton CM, Blanchard R, Cantor JM (2009) Aging versus stable enduring traits as explanatory constructs in sex offender recidivism: partitioning actuarial prediction into conceptually meaningful components. Crim Justice Behav 36(5):443–465

- Beggs SM, Grace RC (2010) Assessment of dynamic risk factors: an independent validation study of the violence risk scale: sexual offender version. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 22(2):234–251

- Bushway SD, Nieuwbeerta P, Blokland A (2011) The predictive value of criminal background checks: do age and criminal history affect time to redemption? Criminology 49(1):27–60

- Caldwell MF (2007) Sexual offense adjudication and sexual recidivism among juvenile offenders. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 19(2):107–113

- Cann J, Falshaw L, Friendship C (2004) Sexual offenders discharged from prison in England and Wales: a 21-year reconviction study. Leg Criminol Psychol 9(1):1–10

- Cortoni F, Hanson RK, Coache ME (2010) The recidivism rates of female sexual offenders are low: a meta-analysis. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 22(4):387–401

- Doren DM (2006) What do we know about the effect of aging on recidivism risk for sexual offenders? Sex Abuse J Res Treat 18(2):137–157

- Falshaw L, Bates A, Patel V, Corbett C, Friendship C (2003) Assessing reconviction, reoffending and recidivism in a sample of UK sexual offenders. Leg Criminol Psychol 8(2):207–215

- Freeman NJ, Sandler JC (2008) Female and male sex offenders – a comparison of recidivism patterns and risk factors. J Interpers Violence 23(10):1394–1413

- Grove WM, Meehl PE (1996) Comparative efficiency of informal (subjective, impressionistic) and formal (mechanical, algorithmic) prediction procedures: the clinical-statistical controversy. Psychol Public Policy Law 2:293–323

- Hanson RK (2002) Recidivism and age – follow-up data from 4,673 sexual offenders. J Interpers Violence 17(10):1046–1062

- Hanson RK, Bussie`re MT (1998) Predicting relapse: a meta-analysis of sexual offender recidivism studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 66(2):348–362

- Harris GT, Rice ME (2007) Adjusting actuarial violence risk assessments based on aging or the passage of time. Crim Justice Behav 34:297–313

- Harris DA, Knight RA, Smallbone S, Dennison S (2011) Postrelease specialization and versatility in sexual offenders referred for civil commitment. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 23(2):243–259

- Lussier P (2005) The criminal activity of sexual offenders in adulthood: revisiting the specialization debate. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 17:269–292

- Lussier P, Tzoumakis S, Cale J, Amirault J (2010) Criminal trajectories of adult sexual aggressors and the age effect: examining the dynamic aspect of offending in adulthood. Int Crim Justice Rev 20:147–168

- Maltz MD (1984) Recidivism. Academic, Orlando

- Miethe TD, Olson J, Mitchell O (2006) Specialization and persistence in the arrest histories of sex offenders: a comparative analysis of alternative measures and offense types. J Res Crime Delinq 43(3):204–229

- Milner JS, Campbell JC (1995) Prediction issues for practitioners. In: Campbell JC (ed) Assessing dangerousness: violence by sexual offenders, batterers, and child abusers. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Nisbet IA, Wilson PH, Smallbone SW (2004) A prospective longitudinal study of sexual recidivism among adolescent sex offenders. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 16(3):223–234

- Prentky RA, Lee AFS, Knight RA, Cerce D (1997) Recidivism rates among child molesters and rapists: a methodological analysis. Law Hum Behav 21(6):635–659

- Quinsey VL, Rice ME, Harris GT (1995) Actuarial prediction of sexual recidivism. J Interpers Violence 10(1):85–105

- Sandler JC, Freeman NJ (2009) Female sex offender recidivism: a large-scale empirical analysis. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 21(4):455–473

- Serin RC, Mailloux DL, Malcolm PB (2001) Psychopathy, deviant sexual arousal, and recidivism among sexual offenders. J Interpers Violence 16(3):234–246

- Soothill K (2010) Sex offender recidivism. Crime Justice 39(1):145–211

- Soothill K, Francis B, Sanderson B, Ackerley E (2000) Sex offenders: specialists, generalists – or both? Br J Criminol 40:56–67

- Thornton D (2006) Age and sexual recidivism: a variable connection. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 18(2):123–135

- Vandiver DM (2006) A prospective analysis of juvenile male sex offenders: characteristics and recidivism rates as adults. J Interpers Violence 21(5):673–688

- Worling JR, Langstrom N (2003) Assessment of criminal recidivism risk with adolescents who have offended sexually: a review. Trauma Violence Abuse 4(4):341–362

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.