This sample Situational Crime Prevention Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Situational crime prevention is concerned with reducing opportunities for crime. It comprises “opportunity-reducing measures that (1) are directed at highly specific forms of crime, (2) involve the management, design and manipulation of the immediate environment in as systematic and permanent a way as possible, (3) make crime more difficult and risky, or less rewarding and excusable as judged by a wide range of offenders (Clarke 1997: 4).”

Since its inception, situational crime prevention has undergone several refinements, incorporating developments in crime prevention research and practice. Opportunity reduction measures have taken numerous forms and have been found effective in reducing a wide range of crime types. It has also encountered staunch resistance, both on theoretical grounds and on the implications deemed to arise from the implementation of situational interventions.

This research paper charts the development of situational crime prevention. It begins by describing its origins, method, and key principles. Next, it discusses evidence of its effectiveness. This is followed by a review of the major criticisms of situational crime prevention and associated rebuttals. It finishes by outlining future directions for the field.

The Origins Of Situational Crime Prevention

Just as there was evolution before evolutionary theory, there was situational crime prevention before situational crime prevention theory. The core tenet of situational crime prevention is that unwanted actions by others can be averted by changing the immediate circumstances of their prospective behavior. It is not necessary (and indeed it may not be possible) to alter the dispositions inclining them to act in undesirable ways.

Hedgehogs practice situational prevention. In the interests of not being attacked, they have evolved sharp spikes that increase the risk and reduce the reward to those animals that might otherwise attack and kill them. Similarly, skunks have developed smells, butterflies the appearance of large eyes, and stick insects – well – the appearance of sticks, to make them less attractive to or less easily identified by potential predators. Situational prevention can even be seen in plants: think, for example, of stinging nettles, cacti, and bramble bushes.

Humans too invented situational measures long before late twentieth-century criminologists began to articulate the relevant theory. Most of us, for example, carry around with us milled coins. These became commonplace in the seventeenth century as a way of preventing coin clipping, which was then widespread: the face value of the coins was supposed merely to reflect the value of the precious metals of which they were minted, and profit could be made by clipping off and keeping some of the metal but preserving the purchasing power of the coin. Unclipped coins thus went out of circulation as clipped coins had the same exchange value. In terms of Sir Thomas Gresham’s famous aphorism: bad money drove out good.

The same fundamental attribution error may underlie the surprisingly long time it took for both evolutionary theory and situational crime prevention theory to surface. The “fundamental attribution error” refers to the human tendency to explain good and bad by the actions of agents with corresponding good or bad intentions (Ross and Nisbett 1991). Crime is bad so its causes must lie in bad intentions: in particular we should blame bad agents and the source of their wickedness. Indeed, echoes of this are still found in much criminology, which looks for the causes of crime mainly in criminal dispositions borne of bad genes, bad upbringing, or bad social conditions. In response to this, situational crime prevention theory presents revolutionary challenges to much taken-for-granted thinking.

The stimulus to the first formulations of situational crime prevention came from a crisis of confidence in conventional wisdom in the 1970s. Improvements in welfare during the postwar period and the simultaneous increases in crime cast doubt on any notion that there might be a simple causal relationship between deprivation and crime, which would be prevented by improvements in social conditions. Moreover, evaluations of efforts at offender rehabilitation, reflecting the dominant criminological opinion at the time, were not encouraging. The slogan “Nothing Works” came to be believed. Situational crime prevention emerged in the British Home Office and promised an alternative approach that focused on preventing crime events rather than addressing offenders’ dispositions to commit crime. The approach was a pragmatic one. Situational crime prevention seemed to work, and policies might usefully be directed at working out how and why situations could be modified to reduce opportunities for crime.

Theoretical And Methodological Underpinnings Of Situational Crime Prevention

Crime as Opportunity was published by the British Home Office in 1976 (Mayhew et al. 1976). It was followed in 1980 by a paper in the British Journal of Criminology with the title “Situational Crime Prevention” (Clarke 1980). These two papers articulated a fresh agenda for understanding and preventing crime.

Mayhew et al. mainly focus on physical means of reducing crime opportunities. Their starting point, however, is “the extent to which deviance may be a temporal response to the provocations, attractions, and opportunities of the immediate situation” (1976: 1). They refer to Hartshorne and May’s classic study, finding that honesty in children is not a stable attribute but instead that situational changes in opportunity can lead them sometimes to cheat, steal, and lie (Hartshorne and May 1928). Mayhew et al. refer also to research showing the importance of the immediate situation on the behavior of those placed in institutions, such as borstals. The language is of “stimulus conditions,” including “opportunities for action,” providing “inducements for criminality,” which are “modified by the perceived risks involved in committing a criminal act and – in a complex, interrelated way – the individual’s past experience of the stimulus conditions and the rewards and costs involved” (Mayhew et al. 1976: 2–3). Although opportunity had been referred to in passing in previous studies, Mayhew et al.’s argument was that it warranted closer, center-stage attention.

One of the most important grounds for arguing that situational factors are worthy of consideration in their own right was the discovery that changes in the toxicity of the domestic gas supply in the UK had a substantial effect on suicide rates. Mayhew et al. cite a study which found that the 45 % drop in Birmingham’s suicide rate from 122 to 67 per million between 1963 and 1969 was almost entirely attributable to reduced toxicity of the gas supply in that city (there were 87 gasrelated suicides in Birmingham in 1962 but only 12 in 1970). The drop in Birmingham’s suicide rate was twice the national fall. A later study by Clarke and Mayhew (1988) corroborated these findings on a national scale. It might be expected that suicides are not committed lightly, but are provoked by deep feelings of despair and, therefore, can only be prevented by looking at the underlying psychological or social source of these sentiments. Finding that the gradual switch from toxic coal gas to nontoxic natural gas largely accounted for the overall drop in suicides challenged that assumption. Having an easily available method of committing suicide, in particular one that was painless and non-disfiguring, seemed to be associated with suicidal behavior. Removing that method had a substantial effect on suicide rates. Even in relation to this deeply caused behavior, there did not appear to be displacement to alternative methods (an issue we will return to shortly). There are many ways of taking one’s own life. Changing the gas supply can have no influence on the cause of suicidal dispositions. It does not make suicide impossible. It nevertheless produced a substantial effect on total numbers of suicides. If deeply motivated behavior could be prevented by a simple change in the situation, how much more readily might criminal behavior, lacking such profound emotional sources, also be prevented?

Mayhew et al. see opportunities deriving from various sources: potential offenders’ age, sex, and general lifestyle; victims’ status; patterns of daily activity; properties of objects (such as their abundance); physical security; and levels of supervision and surveillance (Mayhew et al. 1976: 6–7). They also spell out variables that would be important in testing opportunity theories, for example, “the greater freedom of men to be away from their homes at night, the density of residential properties in rural as against urban areas, the security of these properties, or the extent to which routes of access to them are visible to neighbours and passers-by” (Mayhew et al. 1976: 7). The main emphasis, however, was on the modifiable features of opportunities, notably “the physical security and surveillance aspects of opportunity” (Mayhew et al. 1976).

The Home Office paper goes on to discuss some examples of opportunity reduction as a means of preventing crime: the use of steering wheel locks to prevent car theft and the effects of design (front or back entry) and staffing (presence or absence of a conductor) on bus vandalism. Both studies find that situational variables were important in generating the crime patterns of interest. The introduction of steering wheel locks to all new cars in the UK, from 1971, reduced their theft but with some displacement to older cars. Areas of buses that were not easily supervised experienced far higher levels of vandalism than those open to surveillance.

Clarke (1980) adopts a more critical stance towards the then prevailing criminology than that found in the Home Office paper. He refers to the widespread “dispositional bias” which sees crime as mainly the preserve of a small minority inclined to criminality and which also continued to inform crime prevention policy and practice. He highlights the practical difficulties in changing criminal disposition or in altering the social conditions deemed to foster criminality, as well as uncertainties over the causal processes at work. He stresses, instead, the potential benefits of looking at crimes as results of consciously made, situated choices, even though those involved may not fully appreciate why they are making their decisions.

Clarke refers to three distinctive concerns of situational crime prevention theory: crime events (rather than criminality), separate categories of crime (rather than all crime), and current conditions for criminal acts (rather than dispositions). Two major types of preventive mechanism are discussed: (a) reduction of physical opportunities and (b) increase in chances of being caught, although (c) housing policies that improve chances of parental supervision of children are also mentioned. Clarke distinguishes between opportunistic offenders, whose crimes are less likely to be displaced by situational crime prevention measures and those who make their living from crime, for whom displacement is more likely. A middle group, who supplement their income from crime, produces the main puzzle, where there are plentiful alternative targets. Clarke speculates that classes of target may be protected by situational measures, for example, when much stronger steel coin boxes replaced vulnerable aluminum ones in British telephone kiosks.

While Clarke’s suggestions marked a wide departure from much criminological thinking at the time, noticeable similarities are observed between the situational approach and developments in several areas of psychology. For example, Clarke’s concerns with criminology’s “dispositional bias” spoke directly to the ongoing person-situation debate between personality psychologists and social psychologists. The then prevailing narrative was that human behavior is best explained by more or less stable traits that make up an individual’s personality. This was challenged by the pioneering work of Mischel (1968), who claimed that personality traits were poor predictors of behavior and that greater attention be paid to situational influences. Later “situationalists” could point to a series of classic experiments, notably Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment and Milgram’s electric shock study that demonstrated the ease with which situational forces could be manipulated in ways that trumped dispositions, often to dramatic effect. There are also hints of behaviorism in Clarke’s remark that “decisions are much influenced by past experience (as) people acquire a repertoire of different responses to meet particular situations and if the circumstances are right they are likely to repeat those responses that have previously been rewarding” (Clarke 1980: 138). Likewise, Clarke acknowledges explicitly that situational crime prevention “is, perhaps, closest to a social learning theory of behaviour” (p. 139). Clarke also notes, however, that situational prevention may owe “something to the sociological model of crime proposed by the ‘new criminologists’” (Clarke 1980). Moreover, towards the end of his paper, he avers that opportunity reduction “is entirely compatible with a view of criminal behaviour as predominantly rational and autonomous” (Clarke 1980: 145).

The Home Office report of 1976 and Clarke’s manifesto for situational crime prevention of 1980 laid the foundations for subsequent developments. These can be considered under the headings of methodology, models of the offender, and classification of preventive techniques.

Methodology

Action research has come to be the main method used in situational crime prevention. In accordance with this, Ekblom (1988) describes the “preventive process” as one involving (a) obtaining data on a crime problem, (b) analysis and interpretation of the data, (c) devising preventive strategies, (d) implementation, and (e) evaluation, with (f) feedback via continuous monitoring of crime.

Because situational measures are applied on the basis of the analysis of specific crime problems, evaluation methods that try to determine whether a specific type of measure, say lighting upgrades or CCTV, is effective are not normally deemed appropriate. Instead action-research-based case studies attuned to the problem context have become the preferred method.

Several tools and analytic techniques to inform situational crime prevention have been developed. In particular:

- Crime pattern analysis has advanced rapidly better to specify the problems to be addressed, as well as their spatial and temporal components.

- Repeat victimization patterns have been very widely found and victimization (by place, person, or target) identified as the best predictor for future risk and hence most deserving of preventive attention.

- The phenomenon of “near repeats” has also been identified: the elevated risks faced by those near to the victimized.

- The CRAVED mnemonic (concealable, removable, available, valuable, enjoyable, and disposable) has been devised to capture the attributes of products that are most likely to be stolen.

- “Crime scripts” are used to tease out the steps involved in committing more or less complex crimes, which can then be drawn on to work out where the most promising points of preventive intervention can be found.

- The “problem analysis triangle” organizes the critical elements that give rise to crime events.

Models Of The Offender: The Rational Choice Perspective

A rational choice model has been proposed for offenders (Cornish and Clarke 1986). The simplest way of understanding how situational measures work is to assume some level of rationality on the part of offenders. A change in the situation leads prospective offenders to reassess the expected costs and benefits from engaging in a particular criminal act. If the change in the situation suggests increased rewards or decreased costs, then more of those at the margins of participation in crime will be drawn in. Likewise, if the change suggests decreased rewards or increased costs, fewer will. Little of the formal apparatus of rational choice theory, as used by economists and game theorists, has been adopted. Rather, the assumption is simply that crime choices are open to influence by changing the expected balance of advantages and disadvantages. Indeed, even if there is a very strong disposition to commit a particular crime, the presence of a police officer at the scene, for example, may be sufficient to lead the individual to decide in the event not to proceed.

The rational choice model does not suggest that each individual carefully considers all the options that are available to determine which course of action will maximize utility. Lack of information, lack of ability, and the costs involved in arduous and prolonged decision-making make that untenable. Rather, potential offenders, like everyone else, operate with “bounded rationality.” This conceives of them as decision-makers who are responsive to changes in situations, but it does not embrace the unrealistic assumption that they are capable, conscious, careful, conscientious, and comprehensive calculators of costs and benefits to estimate expected utility in advance of each choice made.

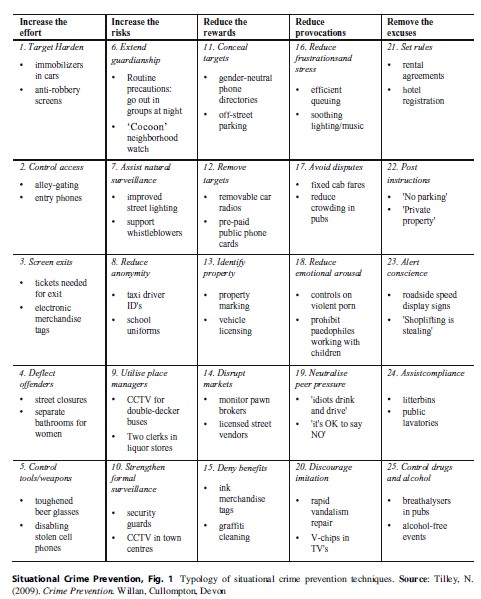

Classification of Preventive Techniques Clarke’s early references to reductions in physical opportunities and increases in the chances of being caught as two categories of situational measures have since been refined and expanded. These have been generalized, respectively, to “increasing effort” and “increasing risk” for the offender. “Reducing reward” was then added, followed by “reminding of rules” (now called “removing excuses”) and “reducing provocation” (Wortley 2001; Clarke and Homel 1997; Cornish and Clarke 2003). Taken together, these form a classification system of situational techniques. Each of the five major headings has a variety of subtypes, as shown in Fig. 1.

The classification of situational techniques serves four purposes. First, it provides a catalogue of the ways in which proximal conditions may affect criminal behavior. Second, it provides a repertoire of possible situational measures that can be countenanced when trying to determine what might be done in relation to a specific crime problem. Third, it provides a user-friendly teaching aide when introducing researchers and practitioners to situational crime prevention. And fourth, it highlights evidence gaps where case studies are required.

In some versions of the typology of techniques, the importance of perception is stressed in relation to risk, reward, and effort. That is, it is recognized that it is not only, or perhaps always most importantly, a question of real increases in effort or risk or real decreases in reward. For the person who might contemplate crime, the issue is that of the risk, effort, and reward that they perceive in relation to the criminal acts of interest. Similarly, provocation and rule recognition are about the ways in which situations are understood.

The Effectiveness Of Situational Crime Prevention

A very large number of studies demonstrating the effectiveness of situational crime prevention have now been undertaken (e.g., see Clarke 1997 for a collection of successful case studies and for a fuller bibliography, with over 200 examples, go to http://www.popcenter.org/ library/scp/pdf/bibliography.pdf.). These cover a range of crime types and different settings. For example, in one study on residential burglary in England, lockable gates were installed to alleyways that ran behind terraced properties. The gates restricted access only to those residents in the affected properties, thereby reducing the opportunities for burglars to enter such properties from the rear, as was evidently the norm. The scheme was found to reduce residential burglary by over a third relative to the control area. Moreover, the scheme was cost-effective, recouping £1.86 for every one pound spent (Bowers et al. 2004). In another study, La Vigne (1994) describes how the implementation of a computerized telephone system in the New York City jail system led to considerable reductions both in illicit phone use by inmates and phone-related violent disputes. In other examples, the effect was immediate, as with the near disappearance of bus robberies in the USA in the 1970s following the implementation of cash drop safes and the shift to an exact-fair payment system.

Such studies do not find some specific measure or type of measure that “works” invariably – specific crime prevention panaceas are not expected. Instead, what they show is that strategies making alterations in the balance of rewards, efforts, and risks or removing provocations or adding rule reminders at the point of crime commission can be devised, which speak to specific crime problems.

The true extent of the effectiveness of situational crime prevention is likely to be higher than that gleaned from the published literature. Retailers and private businesses routinely employ situational measures to protect their assets and prevent loss or theft. Fitting merchandise with electronic tags or placing items in protective displays is commonplace. Such efforts are, however, rarely formally evaluated and hence are typically absent from the scientific literature.

Criticisms Of Situational Crime Prevention

Both the theory and practice of situational crime prevention have been subject to an array of criticisms. The most common are itemized below, followed by the associated rebuttals.

Theoretical Criticisms

Situational Crime Prevention Only Displaces Crime

Arguably, the most enduring criticism of situational crime prevention concerns displacement. It is argued that situational crime prevention simply shifts crime around because it fails to address the underlying “root causes” of crime. Displacement can take several forms: by place, time, method, crime type, or offender. There are enormous measurement problems that mean that it is, in effect, impossible to rule out all forms of displacement. The best that is possible is to assess whether there is displacement where, when, and in relation to which offenses it would be most expected. On that basis, it can be concluded with some confidence that displacement rarely matches the crimes prevented by the application of situational crime prevention (Bowers and Guerette 2009). This is because (a) offenders like to offend in areas with which they are familiar and (b) crime opportunities are not uniformly available. Contrariwise, there is growing evidence that “diffusions of benefits” often occur whereby preventive effects extend beyond the operational range of the measures applied. The possible types of diffusion of benefits match those of displacement. They have been found quite widely, for example, by time, where “anticipatory benefits” include reductions in crime before the preventive measures become operative (Smith et al. 2002), and place, where the geographical range of crime reductions extend beyond the area covered by the measures (Clarke and Weisburd 1994). Proposed explanations for these patterns are that offenders tend to be unaware of the exact boundaries (temporal and spatial) of prevention measures.

Situational Crime Prevention Is Superficial And Simplistic

Crime is complex with many causes. Its explanation calls for attention to a wide range of variables relating to genetics, childhood experience, social structure, and the workings of the criminal justice system. Even if situational variables have any role to play, it is a small one that needs to be considered in the context of a wide range of other causal influences. In placing less emphasis on them, the situational approach is criticized for speaking only to the descriptive components of crime – where and when crime happens – and not to why crime occurs. Situational crime prevention is therefore alleged to be overly simple: lacking the theoretical depth of mainstream criminological theories and merely extending common sense.

The criticism is a weak one. Situational crime prevention draws heavily on three well-established crime event theories: routine activity, rational choice, and crime pattern. It is also underpinned by the widely accepted principle that situations yield causative influences on human behavior, in combination with predisposition, nor can it accurately be considered simple. While the superficial logic is often consistent with day-to-day observations, why the interaction between certain individuals and certain situations under contrasting conditions does or does not generate crime is in no way less complex than the question of why certain individuals do or do not enter a life of crime.

Situational Crime Prevention Is Applicable Only To Instrumental Offenses

Although situational crime prevention may be relevant to instrumental crime where some calculation of returns in relation to effort and risk might reasonably be expected and where, therefore, situational changes that alter expected utility might change an offender’s decisions, for other types of crime, it is much less relevant. Many crimes, especially those involving violence, are more expressive than instrumental or are undertaken under the influence of drugs or alcohol. In these cases, those involved are unlikely to notice or adjust their behavior in response to more or less subtle situational factors.

There are clearly more examples of situational crime prevention being applied to instrumental crimes than there are expressive crimes. But generalizing this pattern to reduce situational crime prevention to an instrumental-only form of crime control is misleading. That many early situational measures relate to acquisitive crimes reflects demand not discordance. Situational crime prevention was developed by researchers based in the British Home Office, which, at the time, was primarily concerned with the high levels of residential burglary and car crime experienced in England and Wales. More generally, there is a situational component to all behaviors. The association of changes in the supply of gas in the UK with dramatic changes in suicide patterns was described earlier. There is also strong evidence to show that situational changes can lead to dramatic reductions in the probability of and harm caused by violence. Bars are a prime example. The shift from glass pint pots to shatterproof receptacles and changes to the internal configuration of bars and nightclubs have all been found to produce positive reductions in alcohol-related assaults in such settings (see Graham and Homel 2008).

Ethical And Practical Criticisms

Situational Crime Prevention Blames Victims

Offenders commit crime and so should be held fully responsible for their criminal behavior. Situational crime prevention suggests that crime problems derive from the opportunities created by those who have not committed any criminal act. Moreover, it suggests that they should accept some responsibility (and in certain cases bear some of the costs) of reducing opportunities. For many critics this is an affront, leading to accusations that situational prevention “blames the victim.” Offenders choose to commit their crimes. Fault lies entirely with them. Moreover, it is the duty of the state in general, and the criminal justice system in particular, to control their behavior.

One suspects that the understandable emotions associated with victim blaming, including most obviously the unwarranted notion that some rape victims may be blamed for wearing provocative outfits, have placed greater prominence on this criticism than is deserved. Situational crime prevention recognizes that targets (broadly defined) can play a causative role in crime events. This is true of people, places, and products. Evidence suggests that certain measures are associated with reduced vulnerability to victimization (as well as its opposite). Most individuals welcome such advice and use it to take recommended precautions against crime. Most individuals would also accept that this is a reasonable expectation and that government agencies are largely impotent to protect them from crime in every situation all of the time. Moreover, there are examples where victims are open to blame and where they may be held culpable for the criminogenic effect of their actions (or inactions). For example, a shop that repeatedly experiences theft because of the way it displays goods, but passes the costs of the crimes to the state, may rightly be blamed for failing to take adequate precautions. Likewise, bar managers who blatantly supply alcohol to already intoxicated patrons may be held responsible for the violent crimes they produce.

Situational Crime Prevention “Criminalizes” Policy, Planning, And Design

The notion that the physical and social architecture of everyday life shapes crime opportunities and that it should therefore be adjusted to reduce crime, risks “criminalizing” areas of policy and practice (shaping them by a situational crime prevention agenda) to the detriment of other ends they may have. Pursuing a situational crime prevention agenda, it is argued, undermines social welfare policy, and diverts resources away from welfare provision and social crime prevention. This also applies to schools, hospitals, retailers, product designers, planners, and architects. In particular it may suggest acceptance, in the name of crime prevention, of an ugly “fortress society.”

Knepper (2009) argues that situational crime prevention contributes more to social policy than the literature suggests. Many situational crime prevention case studies take place in settings that support welfare, namely, housing, hospitals, public transport, and schools. This is most clearly seen in the work of Poyner and Webb on how the design and configuration of social housing influences rates of crime (Poyner and Webb 1991). Effective situational crime prevention can thus increase the likelihood of meeting social welfare objectives.

With respect to the criminalization of products and places, it is trite but worth emphasizing that situational crime prevention amounts to more than simply target hardening. Situational interventions exhibit huge diversity, from high-tech baggage detectors to low-tech bicycle parking stands designed to facilitate improvements in locking practice. Nor are such measures ugly. To situational advocates, particularly those in the tradition of design against crime, manipulating the immediate environment in ways that reduce opportunities for crime without compromising, say, aesthetics, costs, or function holds sovereign (see Ekblom 2008). Finally, while some might consider gated communities as emblematic of a “fortress society,” there are many examples of situational interventions altering the physical environment in ways that promote community togetherness by facilitating neighborly interactions. Lighting upgrades and subsequent increases in pedestrian street usage after dark is a case in point (Painter 1996).

Future Directions For Situational Crime Prevention

There is scope for some theoretical development in situational crime prevention. It is not clear that the rational choice model of the offender is necessary for it. The rational choice model emerged only after the core ideas about situational crime prevention had been formulated, at which point, as indicated earlier, various possible models of the offender were mooted. Moreover, the incorporation of provocation reduction and rule reminders suggests that agents can be responsive to situational changes that operate at the level of feelings and morals as well as at the level of utility calculation.

Displacement is a further area deserving of research. Evidence on the presence of displacement is lopsided. The assessment of spatial displacement and to a lesser extent temporal displacement predominates, while other types of displacement have been little considered, in part because of the challenging measurement problems. The empirical research that is available is also limited in what it can capture, even when technically highly sophisticated. It has long been recognized that displacement is likely to be contingent on factors such as alternative available targets and types of offender motivation. There is scope for further theoretical development to devise propositions that predict what kinds of displacement can be expected in what conditions, again delivering on the suggestions of early papers on situational prevention. The same is true for diffusion of benefits. That theoretical work then needs to be followed by empirical tests.

There is also scope to advance the application of situational crime prevention. While the range of crime types that have been targeted by research and practice has expanded enormously over the past 30 years, there remain important gaps. Studies into “unconventional” crimes, for example, organized crimes of various types (Bullock et al. 2010), terrorism (Clarke and Newman 2006), wildlife crime (Pires and Clarke 2012), and cyber-crime (Newman and Clarke 2003), are available but at present are largely programmatic. Case studies evaluating measures designed to activate provocation-reduction or excuse-removal mechanisms are limited (Guerette 2009). Moreover, situational interventions have rarely been formally evaluated when applied in industrial, office, and agricultural settings (Guerette 2009). More broadly, situational crime prevention has yet to be systematically trialed in developing resource-limited countries, although interest appears to be growing (Pires and Clarke 2012). A key question relates to the challenges of carrying out the preventive process in settings where data are often absent.

The final point concerns exposure and dissemination. Despite being widely advocated and implemented in both North America and much of Europe, it is fair to say that situational crime prevention is yet to capture the imagination of the public and wield widespread influence on policymakers. There is a banality to situational crime prevention that belies its sophistication. This often means it is not credited for providing valid explanations for shifting crime patterns where traditional criminology fails. Nor is it always recognized for its role in producing major crime reductions. Take the much-storied crime drop experienced in several industrialized nations from the early to mid-1990s. Numerous hypotheses have been put forward for such declines, many receiving widespread media coverage. Yet arguably the most convincing explanation of the observed trends relates to the prevalence and quality of in-car (situational) security measures (Farrell et al. 2011). Failure to bring the successes of situational crime prevention to the attention of the public may stymie its progression and confine it to the margins of crime prevention policy and practice.

Bibliography:

- Bowers KJ, Johnson SD, Hirschfield A (2004) Closing off opportunities for crime: an evaluation of alley-gating. Eur J Crim Policy Res 10(4):285–308

- Bullock K, Clarke R, Tilley N (eds) (2010) Situational prevention of organised crimes. Willan, Cullompton

- Clarke RV (1980) Situational crime prevention: theory and practice. Br J Criminol 20:136–147

- Clarke RV (ed) (1997) Situational crime prevention: successful case studies, 2nd edn. Harrow and Heston, Guilderland

- Clarke RV, Homel R (1997) A revised classification of situational crime prevention techniques. In: Lab SP (ed) Crime prevention at a crossroads. Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences and Anderson, Highland Heights/Cincinnati

- Clarke RV, Mayhew P (1988) The British gas suicide story and its criminological implications. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice, vol 10. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 79–116

- Clarke RV, Newman GR (2006) Outsmarting the terrorists. Preager Security International, Westport

- Clarke RV, Weisburd D (1994) Diffusion of crime control benefits: observations on the reverse of displacement. In: Clarke RV (ed) Crime prevention studies, vol 2. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 165–182

- Cornish D, Clarke RV (eds) (1986) The reasoning criminal. Springer, New York

- Cornish DB, Clarke RV (1987) Understanding crime displacement: an application of rational choice theory. Criminology 25:933–947

- Cornish D, Clarke RV (2003) Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: a reply to Wortley’s critique of situational crime prevention. In: Smith MJ, Cornish DB (eds) Crime prevention studies: theory for practice in situational crime prevention, vol 16. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey

- Ekblom P (1988) Getting the best out of crime analysis. Home Office, London. Crime prevention unit series, Paper No. 10

- Ekblom P (2008) Designing products against crime. In: Wortley R, Mazerolle L (eds) Environmental criminology and crime analysis. Willan, Cullompton, pp 195–220

- Farrell G, Tseloni A, Mailley J, Tilley N (2011) The crime drop and the security hypothesis. J Res Crim Delinq 48:147–175

- Graham K, Homel R (2008) Raising the bar: preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs. Willan, Cullompton

- Guerette RT (2009) The pull, push and expansion of situational crime prevention evaluation: an appraisal of thirty-seven years of research. In: Tilley N, Knutsson J (eds) Evaluating crime reduction initiatives, vol 24, Crime prevention studies. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 29–58

- Guerette RT, Bowers K (2009) Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefit: a systematic review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology 47(4):1331–1368

- Hartshorne H, May MA (1928) Studies in deceit. Macmillan, New York

- Knepper P (2009) How situational crime prevention contributes to social welfare. Liverp Law Rev 30:57–75

- La Vigne NG (1994) Rational choice and inmate disputes over phone use on Rikers Island. In: Clarke RV (ed) Crime prevention studies, vol 3. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 109–125

- Mayhew PM, Clarke RV, Sturman A, Hough JM (1976) Crime as opportunity. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London. Home Office Research Study, No. 34

- Mischel W (1968) Personality and assessment. Wiley, New York

- Newman GR, Clarke RV (2003) Superhighway robbery: preventing e-commerce crime. Willan, London

- Painter K (1996) The influence of street lighting improvements on crime, fear and pedestrian street use, after dark. Landsc Urban Plan 35(2–3):193–201

- Pires S, Clarke RV (2012) Are parrots CRAVED? An analysis of parrot poaching in Mexico. J Res Crime Delinq 49:122–146

- Poyner B, Webb B (1991) Crime free housing. Butterworth Architect, Oxford, UK

- Ross L, Nisbett RE (1991) The person and the situation: perspectives of social psychology. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Smith MJ, Clarke RV, Pease K (2002) Anticipatory benefit in crime prevention. In: Tilley N (ed) Analysis for crime prevention, vol 13, Crime prevention studies. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey

- Wortley R (2001) A classification of techniques for controlling situational precipitators of crime. Secur J 14(4):63–82

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.