This sample Surveys On Violence Against Women Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The general consensus to measure violence against women is that population-based standalone surveys are the instruments of choice for collecting statistics on the victimization of women while recognizing that a well-designed module within a general or other purpose survey would be an appropriate tool as well. Several countries have measured violence against women using different types of survey methods. This research paper examines different ways of measuring violence against women giving examples of national and multi-country surveys.

Introduction

The international community has been concerned with violence against women (VAW) or gender-based violence for a number of years. The first United Nations resolution on “Abuses against women and children” was adopted in 1982 calling upon the Member States to “take immediate and energetic steps to combat these social evils.” The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1979. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) monitoring the national implementation of the Convention defines gender-based violence as violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental, or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, and other deprivations of liberty.

In 1993, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women which also introduced the first internationally agreed upon definition on violence against women:

For the purposes of this Declaration, the term “violence against women” means any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life. (United Nations 1993)

Soon after the adoption of the Declaration in 1993, the lack of reliable data on gender-based violence was recognized. The United Nations Beijing Platform of Action in 1995 recommended the collection of prevalence data to better understand different forms of violence against women. The recommendation has been repeated several times in different international forums.

The hidden nature of gender-based violence makes it difficult to measure its prevalence. Police records reflect no more than the tip of the iceberg. Victimization surveys have been seen as key to reveal the experiences of the victims of violence against women which could not be captured in the official records. The first large scale victimization surveys focusing on gender-based violence were carried out in the Netherlands and Canada. The prevalence rates for sexual violence and other violence were generally seen as shocking and caused disbelief. Soon after, other countries started to carry out surveys with similar results. Most violence against women surveys have been done at the national level. Comparative research involving several countries has proven to be problematic because of differences in cultural and legal definitions and data collection methods. However, there are now a growing number of comparative studies on different aspects of violence against women even though the number of countries participating in these surveys has been rather limited.

Measuring Violence Against Women

Indicators Of Violence

Much of the research on violence against women has focused on domestic violence and intimate partner violence (IPV), but gender-based violence is a much wider issue. The United Nations, true to its commitment to human rights, has played an important role in broadening the concept. Gender-based violence can take many forms, and it can take place within or outside the family; it can occur in the workplace, the doctor’s office, in state institutions, on the street, or other public places. The victims may be children, adults, or the aged, and the offenders can be total strangers or those that are known to the victim. Violence can take the form of harassment, emotional and psychological violence, economic abuse or exploitation, sexual and physical assault, or murder. Even though many forms of violence against women are criminalized, in many parts of the world women still experience violence outside the reach of the law. It is virtually impossible to capture this very broad range of harmful practices by any standardized measurement process (Kangaspunta and Marshall 2012).

Gender-based violence is a universal phenomenon which takes different forms in different cultural, social, and economic contexts. Our knowledge about the different forms of violence against women is spread very unevenly across the globe, the most developed countries often having the most sophisticated and elaborate survey data and record-keeping systems. This situation is likely to improve in the future, since important progress is being made on the development of global statistical indicators of violence against women.

In 2006, the United Nations adopted a resolution on “Intensification of efforts to eliminate all forms of violence against women” requesting the Member States to ensure systematic collection and analysis of data. Also, the Statistical Commission was requested to develop a set of possible indicators on violence against women in order to assist States in assessing the scope, prevalence, and incidence of violence against women.

Following the request of the resolution, the United Nations Statistical Commission adopted a list of indicators on violence against women which are based primarily on two criteria, that is, on the availability of data at the national level and the seriousness of the violence itself. The below list is suggested to be a starting point for initiating further work on identifying the most appropriate measurements:

- Total and age-specific rate of women subjected to physical violence in the last 12 months by severity of violence, relation-ship to the perpetrator(s), and frequency

- Total and age-specific rate of women subjected to physical violence during lifetime by severity of violence, relationship to the perpetrator(s), and frequency

- Total and age-specific rate of women subjected to sexual violence in the last 12 months by relationship to the perpetrator (s) and frequency

- Total and age-specific rate of women subjected to sexual violence during lifetime by relationship to the perpetrator(s) and frequency

- Total and age-specific rate of women subjected to sexual or physical violence by current or former intimate partner in the last 12 months by frequency

- Total and age-specific rate of women subjected to sexual or physical violence by current or former intimate partner during lifetime by frequency

In addition, harmful practices including female genital mutilation/cutting and early marriage were considered for inclusion in the indicators list. Also, a number of other manifestations of violence against women were identified that need to be assessed as possible topics for measurement, such as psychological and economic violence, stalking, physical and sexual violence in childhood, forced marriage, discrimination and economic violence at work, trafficking in women, impact of incidence of sexual violence against women on sexually transmitted diseases and HIV/AIDS, assessing risk factors, assessing the extent to which women recognize the suffered violence as a crime, and the percentage of hidden violence unreported to the authorities, or, indeed, even within the community.

It should be pointed out that currently only impressionistic and qualitative information is available for many countries. It is often collected by non-governmental organizations or, for those countries which lack accessible academic research on the topic, provided by the news media. In addition, in some countries we can glean information about gender-based violence through a review article by a local scholar (e.g., Simister et al. 2010; Wasileski and Miller 2010).

One of the most difficult tasks in measuring violence against women is to operationalize the definition of violence against women. During the1990s, there was a considerable controversy over the concepts and terms used in different studies. “Conflict tactics” was used to describe how couples try to settle their differences. Some other studies used rather “violence” and “force” to describe the incidences of violence against women. Also, the question on whether the act or the impact of the act should be measured created prolonged discussion (Walby and Myhill 2001).

Currently, it is widely accepted that surveys should use specific behavioral measures of a range of types of violent acts rather than general terms such as violence or assault. This can at least partly prevent different interpretations of violence among the respondents who might have individual and culture-bound understandings of what constitutes violence. For example, the International Violence against Women Survey used a list of concrete violent acts in its questionnaire including acts like throwing, hitting, pushing, grabbing, twisting arm, pulling hair, slapping, kicking, biting, strangling, suffocating, burning, scalding, and using a knife or gun. Also different acts of sexual violence were mentioned as well as the impact of violence and the steps victims take to obtain help (Johnson et al. 2008).

Measuring Prevalence

Official, administrative records, in particular police and court statistics, have as said limited capacity for measuring the prevalence and incidence of violence against women. Lack of victim willingness to report the incident to the police and reluctance by the police and court officials to record such reports in an adequate manner have historically been cited as impediments to using official data to measure violence and crime. Police statistics may be seen as measures of the criminal justice system’s response to crime, rather than as measures of the crime itself. Police statistics about violent crimes against women such as sexual assault and rape, physical assault, and partner violence can be seen as indicators of social sensitivity and changing norms with regard to acceptable levels of interpersonal violence (see, for example, Mucchielli 2010). A number of countries now have specific legislation to record intimate partner violence or the more inclusive concept of domestic violence. However, these statistics primarily measure the social response of victims, bystanders, service providers, and the police to victimization (Kangaspunta and Marshall 2012).

The general consensus to measure gender-based violence is that population-based standalone surveys are the instruments of choice for collecting statistics on violence against women while recognizing that a well-designed module within a general or other purpose survey would be an appropriate tool as well. Several countries have measured violence against women using different types of survey methods. Targeted surveys usually cover all forms of violence against women including physical violence, sexual violence, intimate partner violence, and threat of violence. In some cases, also harassment and stalking have been studied.

Some countries use a specific module on partner violence which is added to general victimization surveys or to health surveys to assess gender-based violence. Also, a self-completion module about personal physical and sexual victimization has been added to the general victimization surveys. In some countries, only some forms of violence against women have been studied, usually addressing partner violence and sexual violence.

Surveys have also been targeted in different ways in different countries. In some countries, only women were included in the survey; in other countries also men could participate. Also age of the respondents differ: in most surveys the minimum age has been 18, while the maximum age has varied. The UN Statistical Commission recommends the surveys to be started from age 15.

The mode of interviewing has varied in different countries. Violence against women surveys have been conducted by interviewing respondents face-to-face or over the phone; also mailed questionnaires, self-completion on a computer, or combined methods have been used. While some research argues that the use of different methods might have an impact on the data collection, some others have not found much evidence for this. Face-to-face interviewing can build up more rapport between the interviewer and the respondent making it easier to speak about victimization experiences. On the other hand, the anonymity of telephone-based interviews and self-completed interviews may increase the likelihood to reveal sensitive information. In any case, the enquiry mode may have an impact on the response rate. In general, mailed questionnaires tend to have the lowest response rate compare to the other methods (Walby and Myhill 2001). However, the impact of the enquiry method might be different in different countries depending on cultural and other factors. For example, the first violence against women survey in Finland was conducted using a mailed questionnaire with a relatively high response rate of 70 % (Heiskanen and Piispa 1998, p. 8).

Violence against women data drawn from general victimization surveys should be interpreted with caution for many reasons. General surveys might not be able to include specific-enough questions on experiences of violence, and they may lack sensitive question wording. Also lack of selection of and training for interviewers needed to sensitively conduct interviews or the use of male interviewers may have an impact on the willingness to disclose painful memories of violence. Lack of efforts to facilitate victims to speak about their experiences such as ensuring privacy as well as the broad scope of crime victimization surveys not allowing adequately to address sensitive issues might prevent women to disclose their victimization experiences (Johnson et al. 2008, p. 12).

Also, data collection methods based on face-to-face or telephone interviews might lower the reporting of these crimes. When comparing different methods used in the British Crime Survey, it was noticed that prevalence rates for domestic violence from the self-completion method are around five times higher than rates obtained from face-to-face interviews (Flatley et al. 2010, p. 58).

The International Crime Victim Survey (ICVS) which has been carried out since 1989 includes questions on sexual violence which could be relevant in measuring violence against women. However, there are only small changes in the average sexual assault against women 1-year prevalence rate which varies between 0.6 % and 1% in different sweeps. Measuring violence against women based on ICVS is not easy, and the figures should be interpreted with caution as mentioned above. Relatively low numbers of female respondents as well as low figures on sexual violence experiences make it difficult to ascertain statistically significant differences. Some findings also suggest that rates of sexual offences are less stable over the years than those of other types of crime. This may indicate that media campaigns or other measures can temporarily raise awareness about sexual violence which in turn increases the reporting of these incidents (van Dijk et al. 2007, p. 77). Even so, national victimization surveys (with larger samples) when used with due caution, may be a useful source for estimates of the rate of victimization of women.

National Violence Against Women Surveys

Targeted Stand-Alone Surveys

Targeted stand-alone surveys have been carried out in many countries. Examples of the first such surveys can be found in Australia, Finland, and the USA, besides Canada and the Netherlands. The first Women’s Safety Survey was carried out in Australia in 1996 to provide information on women’s safety at home and in the community and to depict the nature and extent of violence against women in Australia (Mc Lennan 1996). The survey was repeated in 2005 as part of the Personal Safety Survey in Australia (ABS 2005) updating the information of the first survey concerning women’s experiences of violence (Phillips and Park 2006). In Australia both male and female violence against women was studied, and the focus was on the experiences during the previous 12 months or during the relationship. In 1996, around 7 % of the respondents had experienced violence during a 12-month period; the corresponding figure in 2005 was around 6 % (ABS 2005).

In Finland, the first national survey on men’s violence against women and its consequences was carried out in 1997 (Heiskanen and Piispa 1998). Also in Finland, the survey was repeated, and the second report on Violence against Women in Finland was published in 2006 presenting information about the prevalence, patterns, and trends of violence committed by men against women in 2005. Also, figures on fear of violence and how victims have sought and received help from different agencies were presented. The results showed that in 1997, 40 % of women aged 18-74 had at least once been exposed to men’s violence or threats since the age of 15. In comparison, the percentage was 44 in 2005. In general, there were only small changes between 1997 and 2005 in women’s violence experiences, the most significant being the decrease of intimate partner violence and the increase of work-related violence (Piispa et al. 2006).

The National Violence Against Women (NVAW) Survey was carried out in 1995 and 1996 in the USA, and it sampled both women’s and men’s experiences with violent victimization. Respondents to the survey were asked about physical assault, forcible rape, and stalking they experienced at any time in their life by any type of perpetrator. Like the other surveys already mentioned, the US Survey showed that violence against women was widespread: nearly 60 % of surveyed women said they were physically assaulted either as a child or as an adult. The survey also showed that many American women were raped at an early age. Out of all women surveyed who said they had been the victim of a completed or attempted rape at some time in their life (18 %), 54% were younger than 18 years when they experienced their first attempted or completed rape. The survey showed that violence against women in the USA was primarily intimate partner violence. Twenty-two percent of all surveyed women and 64 % of those who reported being raped, physically assaulted, and/or stalked since age 18 were victimized by a current or former husband, cohabiting partner, boyfriend, or date. Only 7 % of all men and 16 % of victimized men had similar experience of intimate partner violence (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000, pp. iii–iv).

NVAW was a onetime survey which has not been compared with any information collected after the survey. However, the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) has included a special module to their general victimization survey from 1993 to 2008. The findings cover nonfatal and fatal violent crimes committed against females including nonfatal intimate partner violence (IPV), fatal IPV, rape and sexual assault, and stalking. The victimization survey includes women and girls age 12 or older (Catalano 2009).

One of the first violence against women surveys was carried out in Ghana in 1997 where 3,047 women and men aged between 15 and 72 years were interviewed throughout the country. The high number of languages made the survey particularly challenging in Ghana since the country has more than 27 local languages. All the terms used in the study were dually translated into eight local languages representing the main ethnic groups. Another challenge was the access to the people especially women, because in many cases women need permission from husbands/household heads for interviews. Households also needed to confer with chiefs and elders (Ardayfio-Schandorf 2005).

The violent acts identified in the study included wife beating, rape, defilement, widowhood rites, forced marriages, and female circumcision. Around 23 % of the female respondents reported that they have been beaten by their husbands or boyfriends. Six percent of the female respondents stated that they had been defiled; 78 % of the perpetrators were either close relations, acquaintances, or family friends. Eight percent of women said they had been raped; 59 % of the respondents said they never reported these cases to anybody. On forced marriage, 22 % of the married females stated that their parents decided for them, and 30 % of the females reported that their parents and other closer relatives chose their partners for them. In addition, 12 % of the female respondents indicated that they have been circumcised. Respondents were also asked about widowhood rites. Thirty-one percent of widowed respondents said they were being asked to marry their dead husband’s brother. Other widowhood rites which the respondents mentioned include shaving of hair, ritual bath, being confined to a room for days, and wearing of rope around the neck (ArdayfioSchandorf 2005).

The latest targeted stand-alone surveys include the Nationwide Survey on Domestic Violence Against Women in Armenia, 2008–2009 and the National Research on Domestic Violence Against Women in Georgia in 2009, as part of the UNFPA project on Combating Gender Based Violence in the South Caucasus which was launched in April of 2008 (UNFPA 2008). In the Netherlands large scale surveys of violence against women have been conducted in 1988, 1997, and 2010 (Van der Veen and Bogaerts 2010).

General Victim Surveys With Special Module

Canada was the first country to carry out a series of large scale-targeted survey to measure violent victimization of women aged 18 and above. The survey found that 51 % of women had experienced violence at some point of life out of which 39 % was sexual violence, 34 % physical violence, and 29 % intimate partner violence (Statistics Canada 1993). The survey established a baseline to measure violence against women in Canada, and it was used to include a module on spousal violence in the Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey (GSS) on victimization which is carried out every 5 years which collects information of Canadians aged 15 years and older; a spousal violence module has been used in 1999, 2004, and 2009 surveys. Sexual assault on the other hand is covered as one of the eight crime types addressed routinely in the general survey (Johnson 2006).

In Denmark, the survey information on violence against women is collected through health-related surveys. The 2000 and 2005 national health interview surveys included a self-administered questionnaire on violence against women including questions on specific forms of violence (Helweg-Larsen and Frederiksen 2008).

For France, there are two different types of surveys available. First, there is the general victimization survey in the Paris region conducted every 2 years between 2001 and 2009. It is not a national population-based survey, but it does cover a large population (representative sample of 10,500 households). This survey includes questions about sexual violence, sexual assault by an intimate, insults, and threats. Estimates of two-year victimization rates are possible. Since 2006, a more focused survey “Cadre de vie et securite” (CVS) is conducted annually by the Observatoire national de la delinquance (OND). This national survey has a representative sample of about 17,000 households. This survey uses a confidential self-completion module on personal violence asking respondents between ages 18 and 75 about annual victimization by physical or sexual violence, either by members of their household or by non-family members (INHESJ 2010).

Since 2004/2005, the yearly British Crime Survey (BSC) has included a self-completion module asking respondents aged between 16 and 59 about their experiences of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and stalking (Smith et al. 2011, p. 69). With this method the sensitive nature of the victimization related to violence against women is taken into consideration, and reporting of these crimes is evidenced to be higher (Flatley et al. 2010, pp. 56, 58).

Comparing Victimization

Multi-Country Violence Against Women Surveys

As shown above, because of several differences in national surveys, they cannot be used to compare the level of victimization across different countries. For that reason, international surveys were developed where victimization data were collected in several countries using the same methodology in order to allow comparison between different countries. However, these surveys also have challenges particularly with the translation of questionnaires, interpretation of concepts, structural differences of societies, and other cultural issues.

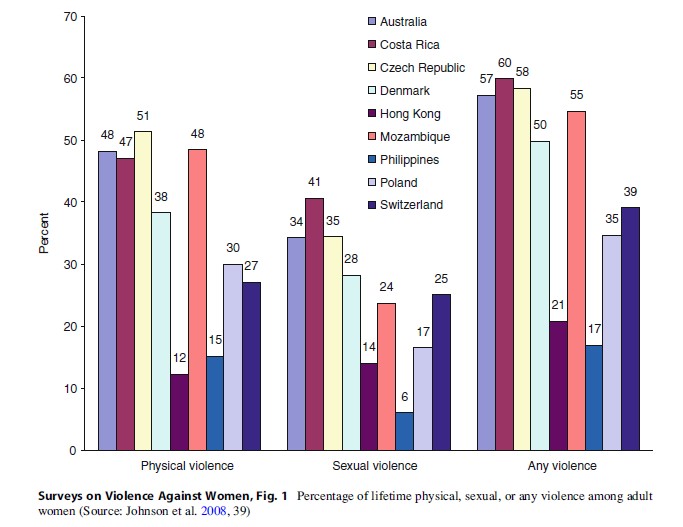

The International Violence Against Women Survey (IVAWS) was specifically designed to target violence by males against women, assessing the level of victimization of women in a number of countries worldwide. The IVAWS relies largely on the methodology of the International Crime Victim Survey (ICVS). Between 2003 and 2005, standardized surveys were carried out in Australia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Hong Kong, Italy, Mozambique, the Philippines, Poland, and Switzerland. The main findings of the IVAWS are:

- Between 35 % and 60 % of women in the surveyed countries have experienced violence by a man during their lifetime.

- Between 22 % and 40 % have experienced intimate partner violence during their lifetime.

- Less than one third of women reported their experience of violence to the police; women are more likely to report stranger violence than intimate partner violence.

- About one fourth of victimized women did not talk to anyone about their experiences (Johnson et al. 2008) (Fig. 1).

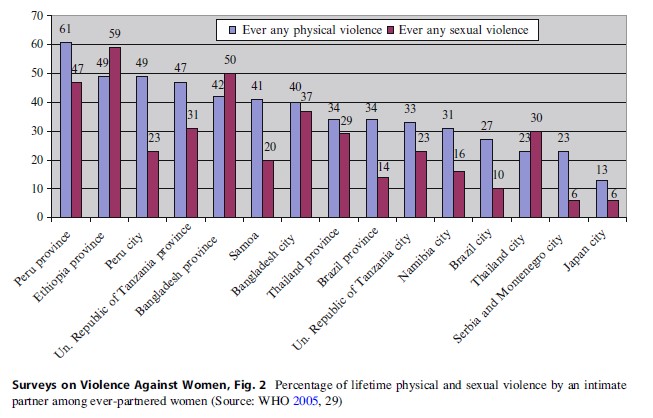

The WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women collected data from over 24,000 women between 2000 and 2003 in the following ten countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Japan, Peru, Namibia, Samoa, Serbia and Montenegro, Thailand, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The study estimated the prevalence of physical, sexual, and emotional violence against women, with particular emphasis on violence by intimate partners. The study consisted of standardized population-based household surveys which were carried out in different locations. In five countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Peru, Thailand, and the United Republic of Tanzania), surveys were conducted in the capital or a large city and one province or region, usually with urban and rural populations. One rural setting was used in Ethiopia, and a single large city was used in Japan, Namibia, and Serbia and Montenegro. In Samoa, the whole country was sampled. The results showed that among women aged 15–49 years:

- Between 15 % (Japan) and 70 % (Ethiopia and Peru) of women reported physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner.

- Between 0.3 % and 11.5 % of women reported experiencing sexual violence by a nonpartner.

- The first sexual experience for many women was reported as forced – 24 % in rural Peru, 28 % in Tanzania, 30 % in rural Bangladesh, and 40 % in South Africa (WHO 2005) (Fig. 2).

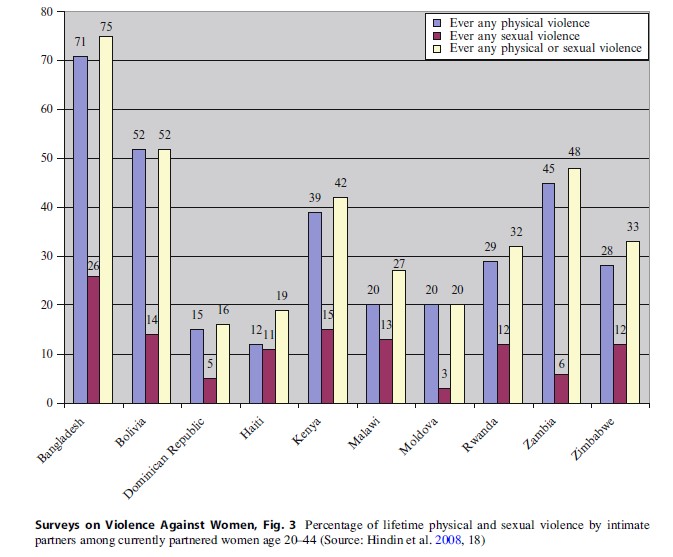

Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are nationally representative household surveys that provide data for a wide range of topics in the areas of population, health, and nutrition. They also include a module on domestic violence assessing the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) among married or cohabiting women. A comparative analysis was carried out based on data collected between 2001 and 2006 in ten developing countries including Bangladesh, Bolivia, Cambodia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Egypt, Haiti, India, Kenya, Malawi, Moldova, Nicaragua, Peru, Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The survey analysis showed that there was wide variation across countries in the prevalence of physical or sexual violence experienced by women and perpetrated by their partners: from 75 % in Bangladesh to 16 % in the Dominican Republic. The highest reported rates of physical violence were in Bangladesh (71 %), Bolivia (52 %), and Zambia (45 %), and the lowest reported rates were in Haiti (12 %) and the Dominican Republic (15 %). The highest rates of sexual violence were reported in Bangladesh (26 %), Kenya (15 %), and Bolivia (14 %), whereas the lowest rates were reported in Moldova (3 %), the Dominican Republic (5 %), and Zambia (6 %) (Hindin et al. 2008) (Fig. 3).

Ongoing Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) can be found in many parts of the world; the latest ones were finalized in 2011 in Angola, Ethiopia, Liberia, Madagascar, Nepal, and Rwanda (Measure DHS 2012).

A standardized survey is also being carried out in all 27 European Union countries including the candidate country Croatia on women’s wellbeing and safety in Europe. The survey will involve standardized face-to-face interviews with about 1,500 women in each country. The interviews will cover women’s experiences of violence including physical, sexual, and psychological violence, harassment, and stalking by current and former partners and non-partners. The survey will also look at violence experiences in childhood in order to create a comprehensive picture of women’s experiences of violence during their lifetime (FRA 2012).

Trend Analysis

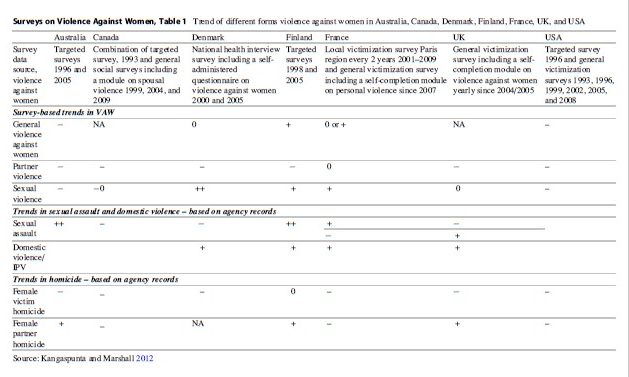

When trends in violence against women are measured, the comparison is not done between countries but within countries based on information from different time periods. For many reasons, the level of violence against women differs significantly between countries, but that is not the focus of a trend analysis. Rather, the interest is in seeing if the data suggest that the level of violence is increasing, decreasing, or remaining about the same in countries across the globe. An important methodological advantage of comparing trends across countries (rather than levels at one point in time) is that this tends to minimize the comparability measurement problems which hamper international comparisons of levels of violence (Marshall and Summers 2012).

A proper trend analysis is possible only if there is sufficient survey information on violence against women covering a prolonged time period. In a recent article Kangaspunta and Marshall (2012) found only seven countries with (repeated) victim surveys related to violence against women. They were Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, UK and the USA. There are also other countries which have conducted repeated violence against women surveys; however, they do not necessarily allow for a trend analysis. The case of Belgium presented below clearly shows some of the challenges of trend analysis.

In Belgium, three large-scale studies were conducted on the prevalence of gender-based violence in 1988, 1998, and 2009. The first study in 1988 analyzed incidences of violence against women; the second study in 1998 was extended to men. The 2009 survey studied the occurrence, forms, and severity of the physical, sexual, and emotional abuse to which women and men are exposed. These studies illustrate some of the difficulties performing trend analyses. While the 1998 study was exclusively concerned with violent experiences over the course of the respondents’ whole life, the 2009 survey included also the experiences during the past 12 months. In the 1998 survey, a violent act was defined in a detailed manner listing 17 acts of physical and 24 acts of sexual violence; in the 2009 study violence was measured in a more synthetic manner, by grouping physical acts into three questions and one general question on sexual abuse.

In the Belgian surveys of 1988 and 1998, the age group included in the sample ranged from 20 to 50 years; the 2008 survey studied individuals between the ages of 18 and 75. In the case of the 2009 study, only abuse experienced in adult life (after the age of 18) was taken into account, whereas the figures for 1998 concern abuse experienced over the respondent’s lifetime. Also, the 1988 survey was conducted using faceto-face interviews, while the more recent surveys were carried out either over the phone or online. In the report presenting the findings of the 2009 results, the authors conclude that – given the differences in methodologies – the surveys do not adequately support trend analysis (Pieters et al. 2010).

In the USA, the National Violence Against Women (NVAW) Survey was a onetime effort which has not been compared with any information collected after the survey. The US violence against women trend analysis has been conducted by using data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), 1993–2008 covering nonfatal and fatal violent crimes committed against females including nonfatal intimate partner violence (IPV), fatal IPV, rape and sexual assault, and stalking. The victimization survey included women and girls age 12 or older (Kangaspunta and Marshall 2012).

The results of the trend analysis of violence against women in the most developed western countries suggest a drop in partner violence against women as measured by the standard surveys (Table 1). On the other hand, (nonpartner) sexual violence appears to be increasing. This drop in partner violence is accompanied by an apparent increase in the level of female victimization reported to the police and other agencies. As Table 1 shows, homicides with a female victim were shown to be decreasing (possibly reflecting a general decline in homicides in general) (Kangaspunta and Marshall 2012).

Conclusions

The need to have sound and up-to-date information on violence against women is well recognized both at the national and international level. The United Nations as well as many other international and regional organizations has stressed the need to collect reliable and comparable data on gender-based violence. Many countries have responded to this call since 1993 when the first highly publicized violence against women survey was carried out in Canada. The first surveys were carried out in highly developed western countries only; however, soon after also countries in other regions followed with their own surveys. The latest efforts to conduct such surveys are covering more and more countries in all geographical areas. Also several new initiatives to collect comparative data have recently been launched.

Often, violence against women surveys have focused on intimate partner violence which raises particular concerns in many countries. Also other forms of violence have been studied including sexual violence and violence in public places. In general, all violence against women surveys have greatly increased our knowledge on the victimization of women, showing that high proportions of women in all parts of the world suffer from violence and abuse.

While some women face the dangers at home, most women need to be aware of the risks outside the private space as well. Women’s everyday life contains numerous situations where harassment, abuse, and violence could take place such as during doctors’ appointments, at the workplace, at school and other educational institutions, during leisure time – for example when participating in sports or just when having a walk in a park. Some of the new studies, particularly the survey on women’s well-being and safety in Europe, aim at highlighting these latter forms of violence. The final objective of violence against women surveys should be to generate positive changes so that women all over the world could enjoy everyday life without fear of violence of any sort.

Bibliography:

- ABS (2005) Personal safety survey Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra

- Ardayfio-Schandorf, Elizabeth (2005) Violence against women: the Ghanaian case. Expert presentation at the expert group meeting organized by: UN division for the advancement of women in collaboration with: Economic Commission for Europe (ECE) and World Health Organization (WHO). “Violence against women: a statistical overview, challenges and gaps in data collection and methodology and approaches for overcoming them”, Geneva, Switzerland, 11–14 April, 2005. http://sgdatabase.unwomen.org/uploads/Violence against women in Ghana – paper by Elizabeth Ardayfio-Schandorf.pdf

- Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M (2006) Intimate partner violence in the United States. Bureau of Justice Statistics

- Flatley J, Kershaw C, Smith K, Chaplin R, Moon D (eds) (2010) Crime in England and Wales 2009/10. Home Office Statistical Bulletin 12/10. London, Home Office. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs10/ hosb1210.pdf

- FRA (2012) FRA survey on women’s well-being and safety in Europe. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. http://fra.europa.eu/fraWebsite/ research/projects/proj_eu_survey_vaw_en.htm

- Heiskanen M, Piispa M (1998) Usko, toivo, hakkaus. Kyselytutkimus miesten naisille tekem€ast€a v€akivallasta. Tilastokeskus. Tasa-arvoasiain neuvottelukunta. Oikeus 1998:12. Sukupuolten tasaarvo. SVT. Helsinki

- Heiskanen M (2006) Miesten Naisille Tekem€an V€akivallan Kehitys ja Kokonaiskuva. In Piispa, M., Heiskanen, M., K€a€ari€ainen, J. and Sire´n, R. (2006) Naisiin Kohdistunut V€akivalta 2005. Oikeuspoliittisen Tutkimuslaitoksen Julkaisuja 225; Yhdistyneiden Kansakuntien yhteydess€a toimiva Euroopan Kriminaalipolitiikan Instituutti (HEUNI) Publication Series No. 51: Helsinki

- Helweg-Larsen K, Frederiksen ML (2008) Men’s violence against women. Extent, characteristics and the measures against violence – 2007. English summary. Minister for Gender Equality, National Institute of Public Health

- Hindin MJ, Sunita K, Ansara DL (2008) Intimate partner violence among couplesin 10 DHS countries: predictors and health outcomes. Macro International, Calverton, DHS Analytical Studies No. 18

- INHESJ (2010) La criminalite´ en France. Institute National des Hautes Etudes sur la Se´curite´ et de la Justice and Observatoire National de la De´linquance et des Re´ponses Pe´nales (ONDRP)

- Johnson H (2006) Measuring violence against women. Statistical trends 2006. Statistics Canada 2006. Catalogue no. 85–570-XIE

- Johnson H, Ollus N, Nevala S (2008) Violence against women: an international perspective. Springer, HEUNI, New York

- Kangaspunta K, Marshall,HI (2012) Trends in violence against women: some good news and some bad news. In: van Dijk J, Tseloni A, Farrell G (eds) The international crime drop: new directions in research. Palgrave, Basingstoke

- Marshall HI, Summers D (2012) Contemporary differences in rates and trends of homicide among European nations. In: Liem MCA, Pridemore WA (eds) Handbook of European homicide research: patterns, explanations and country studies 2012, pp 39–69

- Measure DHS (2012) Demographic and health surveys. http://www.measuredhs.com/What-We-Do/ survey-search.cfm?pgtype¼main&SrvyTp¼year

- Mc Lennan W (1996) Women’s safety Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra

- Mucchielli L (2010) Are we living in a more violent society? A socio-historical analysis of interpersonal violence in France, 1970s-present. Br J Criminol 50:808–829

- Piispa M, Heiskanen M, K€a€ari€ainen J, Sire´n R (2006) Naisiin kohdistunut v€akivalta 2005. Oikeuspoliittisen Tutkimuslaitoksen Julkaisuja 225; Yhdistyneiden

- Kansakuntien yhteydess€a toimiva Euroopan Kriminaalipolitiikan Instituutti (HEUNI), Helsinki, Publication Series No. 51 Phillips J, Park M (2006) Measuring domestic violence and sexual assault against women: a review of the literature and statistics. E-Brief: http://www.aph.gov. au/library/intguide/sp/ViolenceAgainstWomen.htm

- Pieters J, Italiano P, Offermans A-M, Hellemans S (2010) Emotional, physical and sexual abuse – the experiences of women and men. Institute for the equality of women and men, Brussels

- Simister J, Mehta PS (2010) Gender-based violence in India: long-term trends. J Interpers Violence 25(9):1594–1611, http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/25/9/1594

- Statistics Canada (1993) Violence against women – survey highlights and questionnaire package. Statistics Canada, Canada

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N (2000) Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women, findings from the national violence against women survey, national institute of justice, office of justice programs, U.S. Department of Justice, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington, DC

- UNFPA (2008) Combating gender based violence in the South Caucasus. http://www.genderbasedviolence. net/content/show/4/about-us.html

- United Nations (1993) Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. U.N. Document A/48/49, New York

- Van der Veen HCJ, Boogaerts S (2010) Huiselijk Geweld. WODC, Den Haag, Nederland

- Van Dijk JJM, van Kesteren JN, Smit P (2007) Criminal victimization in international perspective, key findings from the 2004–2005 ICVS and EU ICS. Boom Legal Publishers, The Hague

- Van der Veen HCJ, Bogaerts S (2010) Huiselijk geweld in Nederland: overkoepelend synthese-rapport van het vangst-hervangst-, slachtoffer en daderonderzoek 2007–2010. Den Haag, WODC

- Walby S, Myhill A (2001) New survey methodologies in researching violence against women. Br J Criminol 41(3):502–522

- Wasileski G, Miller S (2010) Review essay: the elephants in the room: ethnicity and violence against women in post-communist Slovakia. Violence Against Women 16:99–125, http://vaw.sagepub.com/content/16/1/99

- WHO (2005) Multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. World Health Organization, Geneva

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.