This sample Transnational Corporate Bribery Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Large-scale investigations involving multinational corporations (MNCs) such as Siemens and BAE Systems – the former involved a system of slush funds used to pay bribes to win overseas contracts, while BAE was investigated by the UK Serious Fraud Office for alleged commissions and hospitality payments to Saudi officials involved in a major arms procurement – demonstrate how large commercial enterprises may be the subject of allegations of bribing public and private officials to further or maintain their business interests.

Some would accept that as the cost of development or the unavoidable interdependence between licit and illicit commerce in “gray” markets, others would argue that corruption and bribery have devastating consequences, in particular for developing countries where much corporate corruption is directed. Increasingly, the argument that corruption is very harmful is having a significant impact on the way international business is seen and has shaped legal frameworks and enforcement practices, particularly in terms of international conventions and business-focused initiatives. These, however, not only raise questions about definitions of what is corruption but also of the causes of corporate corruption. These questions are also central to an understanding of why and where corporate corruption occurs and whether control strategies would work and, if not, why not.

Addressing Transnational Corporate Corruption

What Is Corporate Corruption? Definitions And Disciplines

Bribery is only one offense within the wider term of corruption, as academics and commentators try and encapsulate into a single term that conduct and behavior which reflects private or other partisan interests over official duties in both public and private sectors. Defining “corruption,” has long been the subject of conceptual and definitional debate, in part because of differing country and cultural perceptions and in part because of the wish to seek as near as possible universal definition that allows transnational applicability. The terms bribery and corruption are often used synonymously. Bribery is considered the main aspect of corruption, which is often interpreted more widely in terms of conduct that may be in breach of external criminal or regulatory requirements or deviates from the formal internal expectations, governing holding of an appointment in public or legal entities.

It is possible to locate such conduct and its control in the criminological literature within traditional conceptual debates around “corporate” and “white-collar crime” – the ground-breaking work of Edwin Sutherland (1883–1950) that pioneered criminological research into this area. Sutherland’s investigation of business or corporate crime was based on studying the ways in which “crime” was learned by “differential association.” His focus was very much on corporate wrongdoing in its widest sense (such as restraint of trade, unfair labor practices, and stock manipulation). His themes have been developed, expanded, and adapted by academics subsequently to include computer-related crime, management fraud, and corruption, with an emphasis on motivations, deterrence, criminality, offenders, and recidivism. Other criminologists study corporate corruption within the context of state-corporate crime, including state-initiated corporate crime and state-facilitated corporate crime. These argue that governments either (a) allow corporations to act deviantly on behalf of the former to achieve the former’s objectives or (b) more generally work to minimize any regulation of the latter’s deviant activities.

Whichever the intradisciplinary perspective within criminology, however, the specific topic of corporate corruption has not been successfully defined and conceptualized. Empirical criminological research into corporate corruption, with the exception of a few notable studies (see, e.g., Clinard 1990), is sparse, with most literature either analyzing the broader concepts of corruption and bribery found within other academic disciplines, such as political science, sociology, economics, and law, or taking a broader management handbook approach (see, e.g., Brytting et al. 2011).

Within the field of political science, Joseph Nye offered an early definition of corruption, seeing it as “behaviour which deviates from the formal duties of a public role because of private-regarding (personal, close family, private clique) pecuniary or status gain; or violates rules against the exercise of certain types of private-regarding influence” (1967, p. 419). The definition addresses the key distinction between private and official roles which has continued to be of significance and results in a primary focus on public officials, as can be seen in more recent practitioner definitions:

– World Bank (www1.worldbank.org/ publicsector/anticorrupt/corruptn) – the term corruption covers a broad range of human actions. To understand its effect on an economy or a political system, it helps to unbundle the term by identifying specific types of activities or transactions that might fall within it. In considering its strategy, the Bank sought a usable definition of corruption and then developed a taxonomy of the different forms corruption could take consistent with that definition. We settled on a straightforward definition – the abuse of public office for private gain. Public office is abused for private gain when an official accepts, solicits, or extorts a bribe. It is also abused when private agents actively offer bribes to circumvent public policies and processes for competitive advantage and profit. Public office can also be abused for personal benefit even if no bribery occurs, through patronage and nepotism, the theft of state assets, or the diversion of state revenues. This definition is both simple and sufficiently broad to cover most of the corruption that the Bank encounters, and it is widely used in the literature.

– Transparency International (TI) (www. transparency.org/news_room/faq/corruption_faq) – corruption is operationally defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. TI further differentiates between “according to rule” corruption and “against the rule” corruption. Facilitation payments, where a bribe is paid to receive preferential treatment for something that the bribe receiver is required to do by law, constitute the former. The latter, on the other hand, is a bribe paid to obtain services the bribe receiver is prohibited from providing.

– INTERPOL Expert Group on Corruption (www.interpol.int/Public/Corruption/IGEC) – corruption is any course of action or failure to act by individuals or organizations, public or private, in violation of law or trust for profit or gain.

A more sociological definition that focuses on the social relationships involved in bribery and corruption and develops the legal aspect is offered by Deflem, who defines corruption as a “colonisation of social relations in which two or more actors undertake an exchange relation by way of a successful transfer of the steering media of money or power, thereby sidestepping the legally prescribed procedure to regulate the relation” (1995, p. 243). This second definition highlights the key role of social interaction as well as developing a more normative aspect in relation to socially constructed laws. It also allows private sector-private sector corruption to be explored in a more balanced way.

In a preface to an edited volume of articles on definitions, however, Robert Williams noted: “the first volume in this collection, Explaining Corruption, is more conceptual then empirical. But despite the giant lava flow from the “corruption eruption”, the literature on this aspect of corruption still generates more heat than light. Many contributions appear ideological in character and corruption remains a highly contested concept. We still lack firmly grounded theories of corruption and the shortage of analytically informed empirical inquiries continues. Too many participants in the contemporary corruption debate content themselves with resurrecting tired cliche´s about the topic or with slaying long-dead dragons” (Williams 2000, p. xi).

The difficulties of a definition with universal applicability moves toward subjective interpretation and country-specific relevance, where what may be seen as criminal in one context or country may be unethical in another or acceptable in a third (gift giving is one area where these issues are often debated). For such reasons, other organizations have chosen not to seek a general definition but imply a definition by content. Thus, the OECD argues that

The OECD, the Council of Europe and the UN Conventions do not define “corruption”. Instead they establish the offences for a range of corrupt behaviour. Hence, the OECD Convention establishes the offence of bribery of foreign public officials, while the Council of Europe Convention establishes offences such as trading in influence, and bribing domestic and foreign public officials. In addition to these types of conduct, the mandatory provisions of the UN Convention also include embezzlement, misappropriation or other diversion of property by a public official and obstruction of justice. The conventions therefore define international standards on the criminalisation of corruption by prescribing specific offences, rather than through a generic definition or offence of corruption. (OECD 2008, p. 22. Bold in original)

While specific, legally derived bribery definitions encompass the private sector, the wider definitions, as well as the emphasis on direct private gain, may be less clear (as is the active and passive distinctions and the specific transaction of a bribe for a specific advantage). In particular, taking the definition of bribery in the conduct of the enterprise’s business in Transparency International’s Business Principles for Countering Bribery, “the offer or receipt of any gift, loan, fee, reward or other advantage to or from any person,” may be intended to be an inducement to do something which is dishonest or illegal, but it is not necessarily a breach of trust when the company itself decides to use bribes to secure contracts. Indeed, it should be noted that some countries do not criminalize bribery of the private sector, while others do not prioritize corruption in the private sector that does not involve the public sector. Such a decision may also not be related to a specific contract but to creating a climate of favoritism toward the company. An easier approach may be to view definitions through the OECD’s definition of what is not acceptable:

No offer, promise or give undue pecuniary or other advantage to public officials or the employees of business partners. Likewise, enterprises should not request, agree to or accept undue pecuniary or other advantage from public officials or the employees of business partners. Enterprises should not use third parties such as agents and other intermediaries, consultants, representatives, distributors, consortia, contractors and suppliers and joint venture partners for channelling undue pecuniary or other advantages to public officials, or to employees of their business partners or to their relatives or business associates. (OECD 2011, p. 45)

Given such a breadth of offenses and an increasingly subjective interpretation of corruption, a number of commentators distinguish between what might be considered the core corruption offense of bribery and other offenses (some of which, such as the inclusion of embezzlement or money laundering in the UN Convention against Corruption 2005 (UNCAC), would be termed and indeed prosecuted as fraud, economic crime, or financial crime rather than corruption). Certainly some countries and commentators would attach “corruption” to conduct that, while it may be considered self-regarding or in contravention of their official roles and responsibilities (such as the direction of state resources for election purposes), may be criminalized under general legislation (misappropriation) or may be considered unacceptable or unethical but not necessarily illegal depending on context, circumstance, or country (e.g., the traffic of public officials on resignation or retirement to private appointments in areas or activities relating to their previous employment; see, e.g., DavidBarrett 2011).

Definitions of bribery direct us toward the key actors, relations, processes, objects, and employment settings that exist during the processes of what is essentially a transaction. Distinctions between “active” (i.e., giving, offering) and “passive” (i.e., soliciting, accepting) bribery, or otherwise thought of as “supply” and/or “demand” side bribery, are also made. So defined, bribery poses multiple complexities for international and state agencies aiming to legislate for, control, and regulate corruption, but these agencies and actors are largely concerned with illegal acts. Wider “abuse of public office” or violation of “trust” definitions fall into a gray area of bribery and corruption but, along with issues of noncontract-specific payments (such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act 1977’s reference to bribes to obtain or retain business, the use of facilitation payments or the UK Bribery Act 2010’s reference to excessive hospitality), are also requiring moral definitions or subjective assessments to become more narrowly defined and restrictive legal interpretations.

Corporate Bribery And Corruption: Sources And Causes

One cause of the lack of systematic attention to corporate bribery and corruption is the absence of valid data on its prevalence and practices on which to base definitions and explanations. There is anecdotal information on both public private and private-private sector bribery and corruption, although material on the latter is even thinner than that on the former. The latter, for example, is discussed in material available from consultancies (see, e.g., Control Risks 2009) and occasional academic research. Material on the former within a specific country is more extensive in that it relates to bribery of public officials; data may be obtained from a wide range of academic and practitioner institutions although most of the emphasis has been on the public sector than on the corporate sector.

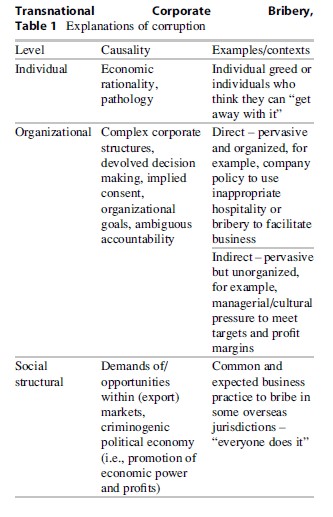

One consequence has been that in attempting to explain the causes of corporate corruption, as with other corporate and white-collar crimes, the lack of empirical research in this area, particularly that which engages with the corporate perspective, makes any concrete analysis difficult and leaves researchers seeking to view corporate conduct through traditional explanations of crime. These have sought to explain crime through classicist or neoclassical models (e.g., rational choice theories), individual and sociological positivist theories (e.g., anomie, strain, learning and biological theories, social disorganization, subcultures), and later social constructionist notions (e.g., labelling perspective). Such theories largely neglected white-collar and corporate crimes, instead focusing on crimes occurring within lower socioeconomic areas by so-called conventional offenders. Corruption, however, could be explained through various sociological/criminological, cultural, politicaleconomic, and structural approaches which resonate at the individual, organizational, and societal levels. Table 1 illustrates these three dimensions although the examples here are not comprehensive and there may be significant interplay and overlap in any given act of corruption.

A number of these attempts to explain the causes of corruption have adopted rational, economic-based models tied in with the level of government intervention. A key example of this is Klitgaard’s (1998, p. 4) corruption formula – “corruption equals monopoly plus discretion minus accountability” – which argues that, whether the activity is public, private, or nonprofit and irrespective of where it occurs, corruption will tend to be found when an organization or person has monopoly power over a good or service, has the discretion to decide who will receive it and how much that person will get, and is not accountable. Furthermore, “corruption is a crime of calculation, not passion” (1998, p. 4). Rational choice theory as applied by Shover and Hochstetler to white-collar crime would also argue that “all criminal decision making represents a single field of study and that much of what has been learned in studies of street criminals and their decision making almost certainly is paralleled in white-collar crime decision making” (2006, p. 3).

This ties in with Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) “general” theory of crime that also adopts this model of rationality, suggesting human nature is motivated by self-interest and a pursuit of pleasure over pain, therefore echoing the earlier classicist notions of Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham. They suggest the official crime data they analyzed showed few differences between “conventional” and “white-collar” offenders in relation to variables such as age, social class, and gender and that short-term gratification is a key feature of conventional and white-collar crime. Individuals’ lack of self-control along with the absence of attachments to others and sufficient controls leads individuals to offend. This approach has been greatly criticized, most notably by Steffensmeier (1989), on the grounds that their sample of white-collar criminals was biased toward lower-class offenders, and by Slapper and Tombs (1999). The latter point out that explanations of crime in relation to human nature do not account for sociological, environmental, cultural, and social structural influences on behavior. In addition, such control theories neglect that organizational crime involves the pursuit of organizational goals ahead of individual gratification (Friedrichs 2007, p. 205).

Economic and individual rationality, then, should be considered only one perspective in understanding the causes of corruption as explanations of the causes of corruption can be found within legal, economic, social, organizational, and cultural reasoning. For example, other explanations of white-collar and corporate crime focus on pathologies at the individual level whereby individual characteristics and personality traits differentiate offenders and non-offenders. It has, for example, been acknowledged that corporations often put such wrongdoing down to “rotten apples in the barrel” albeit such explanations are seen as inappropriate and have little evidence to support any connection between white-collar crime and individual pathologies (see Croall 2001, pp. 83–85). Certain characteristics such as a tendency to take risks, recklessness, ambitiousness and drive, and egocentricity and a hunger for power have been associated with this type of offending, and as Friedrichs notes, “some white collar crime does seem to be difficult to explain without reference to personality and character” (2007, p. 203).

The work of Matza and Sykes (1961) that focused on “techniques of neutralisation” is one theory that has been applied somewhat successfully to corporate crimes where offenders justify or neutralize their behavior. Justifications include “denial of responsibility,” “denial of injury,” “denial of the victim,” “condemnation of the condemners,” and “appeal to higher loyalties.” Such culturally based justifications can demonstrate corporate attitudes toward certain wrongful activities. For example, Chibnall and Saunders (1977), who examined business corruption and bribery in England in a different era, showed that business individuals, despite being fully aware of their illegal actions, were able to justify them by referring to the pervasiveness of such practices in business. As Clinard and Yeager note, “[a] variety of justifications are available to those executives who are confronted with doubt or guilt about illegal or unethical behaviour; these justifications allow them to neutralize the negative connotations of their behaviour” (1980, p. 67). Indeed, as Croall notes, “[s]ome illegal activities are regarded as ‘normal’ business practice and others are readily justifiable as being for the ‘good of’ the organisation” (2001, p. 94).

The Corporate Organization

Much of the organizational deviance literature looks at managers and executives who may not only act deviantly on behalf of the organization but also against it. In looking at the private sector, Punch discusses a number of contextual possibilities that may trigger corporate deviance. These may be structural – markets (either competition or anti-competition factors); size of organizations (which dilutes both control and responsibility); achieving organizational goals; opportunity; total loyalty to the company; corporate culture, and personal, depersonalization in deference to the corporate ideologies and practices; corporate-focused rationalization; business as war; risk-taking; dominant personalities; necessary dirty hands as part of corporate competition; pressure; and rewards, which lead to the development of a “corporate mind.” The mind is attuned to the “signals” from the corporate environment (what they are expected to do, what others are also doing, or what it takes to succeed) that are set by the “fundamental concerns of senior management.. .centred on corporate survival, continuity, power, reputation/face, and profits.. .” (Punch 1996, p. 239).

The question might be asked – deviant in relation to domestic legal frameworks, to legal frameworks in export markets, or to conduct considered acceptable in domestic markets and replicated in export markets? Certainly recent work of criminologists on organizations, culture, and deviance would, as in the case of Clinard and Yeager (1980), argue a shift away from theories of deviance and crime applicable to individuals to a focus on the corporation as a complex organization. By doing so, they sought to adopt organizational theory in their understanding of corporate crime. They state:

[t]he immensity, the diffusion of responsibility, and the hierarchical structure of large corporations foster conditions conducive to organizational deviance. In addition, the nature of corporate goals may promote marginal and illegal behaviour, as may the characteristics and the social climate of the industries within which the firms operate (1980, p. 43).

Organizational understandings of corporate crime, and therefore corporate corruption, take into consideration individual, organizational, and sociological factors which can influence corporate offending, and Schrager and Short succinctly explain this relationship when they state that .. .preoccupation with individuals can lead us to underestimate the pressures within society and organisational structures which impel those individuals to commit illegal acts.. .recognising that structural forces influence the commission of these offences does not negate the importance of interaction between individuals and these forces, nor does it deny that individuals are involved in the commission of illegal organisational acts. It serves to emphasise organisational as opposed to individual etiological factors, and calls for a macro sociological rather than an individual level of explanation (1977, p. 410; see also Punch 1996).

Further certain intradiscipline perspectives argue that such factors cannot be viewed in isolation from the wider political and economic context. Thus, the state-corporate approach “directs attention toward the way in which deviant organisational outcomes are not discrete acts, but rather the outcome of relationships between different social institutions. Second, by focussing on the relational character of the state, the concept of state-corporate crime foregrounds the ways in which horizontal relationships between economic and political institutions contain powerful potential for the production of socially injurious actions. This relational approach, we suggest, provides a more nuanced understanding of the processes leading to deviant organisational outcomes than approaches that treat either businesses or governments as closed systems. Third, the relational character of state-corporate crime also directs us to consider the vertical relationships between different levels of organisational action: the individual, the institutional, and the political-economic” (Kramer and Michalowski 2006, p. 22).

A more extreme analysis within this perspective would propose the organization as reflecting macrolevel influences, which ties in with social structural theories explaining corporate criminality as well as with theories from Marxist scholars who argue that capitalist economic structure and ideology itself is criminogenic. For example, Durkheim’s “anomie” and later strain theories have been applied to white-collar criminals in relation to “boundless aspirations” and “greed” that affect all individuals (see Croall 2001, p. 91). Furthermore, in terms of the economic structure, Slapper and Tombs (1999, p. 141) argue that corporate offending is endemic to capitalism. This creates “amoral” corporations that are focused on profit above business ethics, although ethical business activities may be used as a means of creating profit. On the other hand, other criminologists would argue that it is not:

convincing to assume that all businesses act as “amoral calculators” and would choose to offend but for the availability of serious sanctions.. .The desires to continue in business and to maintain self-respect and the good will of fellow businessmen, go a long way to explaining reluctance to seize opportunities for a once-only windfall.. .Trading competitors (as well as organized consumer groups, unions, and others) can serve as a control on illicit behaviour for their own reasons. Law-abidingness can often be definitely in the competitive interests of companies. Marxist theory has no need to assume that all business crime will be tolerated. Many forms of business misbehaviour made into crimes may reflect changing forms of capitalism or inter-class conflict. At any given period, some corporate crimes, such as anti-trust offences, will not be in the interest of capitalism as a whole, so it is important to distinguish what is in the interests of capitalism from what suits particular capitalists. Even if the latter may succeed in blocking legislation or effective enforcement, at least in the short term, this does not prove that it is capitalism as such which requires the continuation of specific forms of misbehaviour (Nelken 2007, pp. 747, 748).

As Slapper and Tombs note, however, while it is difficult to pinpoint why a company at a point in time may opt for corrupt business dealings or to understand why “normal” rather than pathological organizations should act this way, societal context or culture is crucial: “a capitalist economy constantly pushing people with targets to hit, promotions to seek and emotions to avoid, recessions to try and survive, and so on, can thus be seen as a society likely to engender corporate crime” (Slapper and Tombs 1999, pp. 161–162).

On the other hand, given Nelken’s comments, assumptions about likelihood do not address the absence of corporate corruption in some companies and/or in some countries. Part lies with the increasing extraterritorial reach of developed countries’ law enforcement and justice bodies; part lies with the promotion of international instruments to foster cooperation, asset recovery, and so on. Part lies in the increasing influence in some countries of the corporate governance agenda which sees both corporate value and profitability in promoting corporate social responsibility, environmental protection, fair trade, and organizational standards. In part, it may also be the consequence of other (often related) factors, such as government’s interests, the specific markets in which the companies are working, and the often asymmetrical and inefficient nature of market competition which are likely to impact more on countries exporting internationally than on those with limited exposure to more volatile and corruption-prone contexts.

Countries, Contexts, And Consequences

It is clear that a number of theoretical perspectives and ideas can be relevant to explanations of corporate corruption. Also clear is the complexity between individual, organizational, social structural influences, as well as the legal, economic, and cultural frameworks within which transnational corporations operate. Thus, Slapper and Tombs suggest corporate offending can only be understood in the context of wider political economy and that any theoretical analysis of corporate crime should include various social structures in relation to capitalism and inequality. They suggest that

[k]ey aspects of any such analysis would integrate understandings of the general state of national and the international economy, the nature of markets, industries, and the particular products or services with which particular corporations are involved, dominant ideologies and social values, formal political priorities and the nature of regulation, particular corporate structures, the balances of power within these, the distribution of opportunities within and beyond these, and corporate cultures and socialisation into these (1999, p. 160).

This takes us to corporate bribery and corruption in terms of the international dimension, where the volume of academic and practitioner material is much more extensive. Two points are worth making. First, as discussed below, the anticorruption drivers in terms of corporate bribery and corruption derive from international organizations as part of their development agenda. As a consequence, developed countries associated with that agenda have been those who have increasingly required domestic business to adhere to domestic legislation not to engage in bribery. On the other hand, businesses from emerging economies are also heavily involved in lesser developing countries but whose governments are less committed to enforcement of anticorruption measures (e.g., those of China, India, and Russia have been identified (see Transparency International’s 2008 Bribe Payers Index)). Second, reflecting on Slapper and Tombs’ comments, how business behaves in its domestic market and different international markets may depend significantly on country, context, and product, as well as the propensity of the industry or sector itself to dishonest practices in pursuit of markets and profitability.

Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported in 2009 that “the medicines chain refers to the steps required for the creation, regulation, management and consumption of pharmaceuticals. Corruption in the pharmaceutical sector occurs throughout all stages of the medicines chain, from research and development to dispensing and promotion.. .countries with weak governance within the medicines chain are more susceptible to being exploited by corruption. These countries lack: appropriate legislation or regulation of medicines; enforcement mechanisms for laws, regulations and administrative procedures; conflict of interest management” (WHO 2009). Similarly, the arms trade is known for not only the interdependence between companies and governments, whether through lobbying, revolving appointments, party funding, and export subsidy, or a focus on export-led production, often involving exports to those countries, as one of the few inquiries into international arms trafficking noted, where “the age-old pressures of human nature, greed, the thirst for power and finally unbridled corruption” (Blom-Cooper 1990, p. 131) continues to adversely affect “open societies, the rule of law and national security” (SIPRI 2011, p. 5).

At the same time, countries with poor governance frameworks often provide permissive environments for domestic and international companies, as well as for the behavior of those domestic companies when they too operate in the international markets. Thus, networks and payments in China have provided a means for domestic and international business “to negotiate the unstable and complicated world of China in the early market reform era.” Nevertheless, the traditional guanxi practice which “allowed actors to construct social networks and build relationships of trust, which encouraged investment and facilitated the rise of small businesses,.. .also encouraged a conducive environment for rent-seeking, bribery, collusion and exploitation” (Smart and Hsu 2007, p. 186). When the United Nations undertook its major investigation into the oil-for-food scandal, Chapter III of the report provided a detailed analysis of the individual roles of 23 companies that participated in the payment of kickbacks on humanitarian contracts. The inquiries not only showed a refusal by companies (including European as well as Russian and Chinese companies) to cooperate with the inquiry but an unwillingness to acknowledge that the payments were either known to senior management or were, if known, illegal (see Independent Inquiry Committee 2005).

The apparent continuing absence of business to act responsibly in such markets has also been the subject of a number of international organizations and NGOs, covering healthcare, mineral resources, and oil. Such reports often emphasize the consequences. Thus, in relation to natural resources in one country, the 2009 Human Rights Watch report on forestry in Indonesia estimated that the Indonesian government lost $2 billion in 2009 due to illegal logging, corruption, and mismanagement. The total includes forest taxes and royalties never collected on illegally harvested timber, shortfalls due to massive unacknowledged subsidies to the forestry industry (including basing taxes on artificially low market price and exchange rates), and losses from tax evasion by exporters practicing a scam known as “transfer pricing.” It went on to note that forestry sector corruption has widespread spillover effects on governance and human rights:

The individuals responsible for the losses are rarely held accountable by law enforcement and a judiciary deeply corrupted by illegal logging interests, undermining respect for human rights. In addition, the ability of citizens to hold the government accountable is curtailed by a lack of access to public information. And the opportunity costs of the lost revenue are huge: funds desperately needed for essential services that could help Indonesia meet its human rights obligations in areas such as health care, go instead to line the pockets of timber company executives and corrupt officials (2009, p. 39).

Indeed, attempts to reduce carbon emissions through deforestation by international and regional aid agencies have already been identified as likely to cause further corruption place in countries where corruption is pervasive through the illicit purchase of land and carbon rights by developers and logging companies (see UNDP 2010).

Control Context: Legislation, Conventions, And Initiatives

It has been this level of continuing the failure of business (and on occasion the governments of their home countries) to act “responsibly” at an international level which has led to pressure to criminalize such conduct. A number of countries, primarily in the developed world, have taken steps to regulate corruption in their domestic markets; a lesser number also have regulatory agencies to address corporate standards. Nevertheless, in terms of international corruption, multilateral and bilateral agencies have not only sought to manage corporate misuse of their own funds but also, under continuing pressure from international NGOs, such as Transparency International, Global Witness, and so on, have sought to institute more effective control environments. By doing so at international level, however, the intention has been to address domestic legislation in a way that addresses not only bribery abroad but also the question of domestic jurisdictions being responsible for such extraterritorial conduct.

The international measures include the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Anti-Bribery Convention (the OECD 1997 Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions), the UN Conventions (including the United Nations’ 2003 Convention against Corruption [UNCAC] and, in part, the 2000 UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime [UNTOC]), and numerous regional and EU-level Conventions (including the 1999 Council of Europe Criminal and Civil Law Conventions on Corruption and the 1995 EU Convention on the protection of the communities’ financial interests and the fight against corruption, First and Second Protocol; and the 1997 EU Convention on the fight against corruption involving officials of the European Communities or officials of Member States 1997).

These provide anticorruption frameworks within which to tackle these crimes (although public discourse often refers to corporate “wrongdoing,” “misbehavior,” and so on, rather than “crime”). Furthermore, monitoring and evaluation of national anticorruption policies takes place in the form of UNCAC peer reviews, the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), and the OECD’s Working Group on Bribery, among others, which highlight inadequacies and subsequently recommend legislative, institutional, practical, and structural improvements.

The three international conventions that significantly influence the control of corporate corruption at the national level are the OECD Convention, UNCAC, and UNTOC:

The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention

The OECD Convention was the first and remains the only legally binding instrument focusing on the supply side of bribery. The Convention deals with what is termed “active bribery” in contrast to “passive bribery.” This means the focus is on the offense committed by the person who promises or gives a bribe. That said, the Convention does not use the term “active bribery” in order to avoid nontechnical readers mistakenly viewing the briber as taking the initiative and the recipient as a passive victim (OECD Convention 1997, p. 14, paragraph 1): it is often the case that the recipient will have induced or pressured the briber and thus be more “active.” The Convention seeks a “functional equivalence” among the measures taken by the parties to sanction bribery of foreign public officials and therefore does not require uniformity or changes in fundamental principles of a party’s legal systems (e.g., there is corporate criminal liability in the UK but not Germany). The Convention is highly focused and targeted toward those countries that account for the majority of global exports and foreign investment and introduced the required specific criminalization of the bribery of a foreign public official in international business transactions. It provides a broad and inclusive definition of foreign public official. Senior politicians through managers at state-owned organizations to local police officers would all fall within this definition.

UNCAC

The UNCAC is the first global legally binding instrument in the fight against corruption. It requires the States Parties to implement numerous and detailed anticorruption measures impacting upon their laws, institutions, and practices. The purpose is to aid prevention, detection, and sanctioning of corrupt practices and encourage the cooperation of States Parties. The Convention requires States Parties to establish a range of offenses associated with corruption and attaches particular importance to prevention and the strengthening of international cooperation to combat corruption. It also includes “innovative and far-reaching” provisions on asset recovery and technical assistance and implementation. UNCAC follows an almost identical definition of the term “foreign public official” to that of the OECD Convention but includes also any person holding an “executive” office of a foreign country.

UNTOC

Although UNTOC is the primary international tool for tackling organized crime, it also acknowledges the significant role of corruption in transnational organized crime and therefore requires corruption to be addressed as part of combating organized crime. It focuses only on domestic bribery. UNTOC covers public sector corruption. Of most significance, the Convention requires States Parties to criminalize corruption, with a focus in particular on public sector corruption and bribery of public officials. It further requires effective measures to detect and punish such corruption and significantly requires public authorities to be provided with adequate independence in order to deter the exertion of inappropriate influence of their actions.

Signatories to all such Conventions are required to translate the mandatory components into domestic legislation. All three mention money laundering (although UNCAC makes asset recovery a fundamental principle) and argue for international cooperation in investigating and sanctioning offenders registered in their jurisdiction.

There also a range of corporate-focused initiatives to support corporate anticorruption implementation. Some provide guidance to business, such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises intended to provide voluntary principles and standards for responsible business conduct consistent with applicable laws and the TI Business Principles for Countering Bribery, or specific guidance, such as ICC Guidelines on Agents, Intermediaries and Other Third Parties. Others are more specific and applied. The Global Compact (GC) is a UN initiative to encourage corporate responsibility among private sector companies by asking them to sign up to a set of core values in the areas of human rights, labor standards, the environment, and anticorruption. The World Economic Forum has set up Partnering Against Corruption Initiative (PACI). This engages with chief executive signatories of industry-leading companies in the implementation of a zero-tolerance policy toward corruption and bribery. Other initiatives are directed at specific industry sectors, such as the Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre, the Medicines Transparency Alliance, and Publish What You Pay; the two major initiatives are the EITI and Collective Action in which the first seeks publication by extractive companies of their payments to host governments and the second provides an anticorruption resource for business by focusing on fighting corruption jointly with other companies and stakeholders, including government.

Control Context: Impact And Implications

Much of the international approaches rely on advocacy and influence; international law and international judicial institutions effectively have no jurisdiction in relation transnational and multijurisdictional corporate crimes. Sovereign states, despite agreeing to ensure their domestic legislation allows for extra-jurisdictional policing, face significant difficulties. Anticorruption authorities, limited by procedural, evidential, legal, and financial obstacles, as well as interstate cooperation, are thought to be easily outflanked by corporations that bribe as part of international business transactions. Enforcement frameworks at the national level largely reflect “command and control” regulatory approaches that exercise influence through enforcing standards supported with criminal sanctioning – albeit corporations rarely face criminal liability, instead negotiating civil settlements with prosecutors and enforcement agencies. Historically, however, there have been numerous debates between regulators and between academics as to the most appropriate approach to effective regulation. On the one hand, there are those who believe that compliance to the law requires a punitive policing approach incorporating the use of severe sanctions and criminal prosecution. On the other hand, there are those who advocate an approach more in line with the persuasion of businesses to comply with the law. These polemical approaches have been referred to as models of “deterrence” as opposed to models of “compliance” (Reiss 1984) although some analysts have argued it is a question of “when to punish; when to persuade” (Ayres and Braithwaite 1992, p. 21). It is this latter perspective that largely reflects contemporary thinking on regulation (see, e.g., Black and Baldwin 2010). Enforcement practices alone, however, are insufficient, with more preventive mechanisms required to ensure behavior change within corporations and business. It is here where initiatives such as GC and PACI (see above) can influence the broader regulatory landscape.

The final question is whether or not such initiatives – whether focused on criminalization and sanctions or on voluntary agreements – are effective in managing or reducing corporate bribery and corruption. A number of more mainstream criminologists would argue that the undifferentiated assumptions that see all business is potentially criminogenic all of the time “as an inevitable consequence of capitalism” are too sweeping a generalization. They suggest that “it is well to bear in mind some reservations about the idea that capitalism as such is criminogenic. The argument appears to predict too much crime and makes it difficult to explain the relative stability of economic trade within and between nations, given the large number of economic transactions, the many opportunities for committing business crimes, the large gains to be made, and the relative unlikelihood of punishment” (Nelken 2007, p. 747).

Certainly, policing of corporate offenses both domestically and internationally varies significantly, depending on country, context, and purpose – whether the role of the Elf Aquitaine oil company in party finance in France or the 15–20 % of the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund ($3–5 billion) “wasted” by US companies according to the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (Tarnoff 2009, p. 20) – and how far governments balance their various interests, such as trade, influence, and oil, with commitment to international standards. In terms of the OECD’s own figures on criminal or administrative sanctions, three countries – Germany, Italy, and the USA – were responsible for nearly two-thirds of the cases (232 from a total of 310 between 1999 and 2010 with 38 countries responding).

This raises questions about the geopolitics of integrity because a pragmatic approach by developed countries rules out large areas of the world, including a number of Caspian, Caucasian, and Middle East countries where, as the Economist pointed out, “oil and ethics mix about as well as oil and water” (10 May 2003), those countries whose corruption is overlooked in the continuing pursuit of greater political objectives (whether arms sales, the war on drugs or regional spheres of influence), those countries too big to influence and too powerful to want to listen (such as Russia), or those who are written off as failed states with no strategic or geopolitical value.

Of course, some would argue that the overall developmental agenda that includes the current anticorruption approach is itself shaped by multilateral and key bilateral donors’ perception of the wider developmental trajectory of and objectives for the donor-aided countries and influenced through the uses and conditions attached to their aid and support to achieve this. In terms of both, the preferred direction is toward the “standard liberal democratic practices and norms – representative and responsible government, the rule of law, and the absence of corruption. But it also appears to privilege a neo-liberal faith in the superiority of market economies and in the importance of introducing market mechanisms into the public sector” (see Bevir 2004 p. 2) which benefit developed economies’ businesses as much as, if not more so, developing economies’ businesses. Whether that would resolve the issue of corporate corruption, certainly in export markets, is another question.

Conclusion

This research paper set out to discuss corporate corruption in the context of bribery of public and private officials. Corruption and bribery are broad concepts that incorporate a diverse array of activities, actors, and social relations. Endeavors to conceptualize their meaning and extent, their perpetrators and victims, their regulation and control, or even whether they constitute crime, deviance, immoral behavior, or common business practice have been faced with significant theoretical, conceptual, and methodological challenges. The lack of empirical data adds further to these complex phenomena, as do variations in understandings of the problem within different social contexts and jurisdictions.

Distinctions between “active” and “passive” bribery and “public” and “commercial bribery” at the “international” or “domestic” level create a useful analytical framework for understanding how corporations can use corrupt practices in the context of commerce. But the organization of such complex and serious crimes creates significant challenges for control agencies limited by their jurisdictional boundaries and their traditional enforcement approaches. International conventions have attempted to harmonize the problem through their legal frameworks, using content definitions, rather than analytical definitions, that can be operationalized at the national level. Principles of “functional equivalence” that place emphasis on “goals” rather than “means” ensures the fundamental beliefs of nation states’ enforcement systems remain. How sovereigns deal with the problem of corporate corruption can therefore vary greatly. Sanctioning alone, however, may be insufficient, as long-term behavior change within businesses and corporations that use bribery requires a broader regulatory approach incorporating nonenforcement mechanisms such as self-regulation and anticorruption initiatives. Measuring the impact of such prevention-focused approaches, however, is a difficult task in itself.

Bibliography:

- Ayres I, Braithwaite J (1992) Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press, New York

- Bevir M (2004) Democratic governance, working paper 2004: 5. Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California, Berkeley

- Black J, Baldwin R (2010) Really responsive risk-based regulation. Law Policy 32(2):181–213

- Blom-Cooper L (1990) Guns for Antigua: report of the commission of inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the shipment of arms from Israel to Antigua and transhipment on 24 April 1989 en route to Colombia. Duckworth, London

- Brytting T, Minogue R, Morino V (2011) The anatomy of fraud and corruption. Gower, Farnham

- Chibnall S, Saunders P (1977) Worlds apart: notes on the social reality of corruption. Br J Sociol 28:138–153

- Clinard MB (1990) Corporate corruption: the abuse of power. Praeger Publishers, New York

- Clinard MB, Yeager PC (1980) Corporate crime: the first comprehensive account of illegal practices among America’s top corporations. Collier Macmillan Publishers, London

- Control Risks (2009) Business, corruption and economic crime in central and south-east Europe. Control Risks, London

- Croall H (2001) Understanding white-collar crime. Open University Press, Buckingham

- David-Barrett L (2011) Cabs for hire? Fixing the revolving door between government and business. Transparency International UK, London

- Deflem M (1995) Corruption, law, and justice: a conceptual clarification. J Crim Justice 23(3):243–258

- Friedrichs DO (2007) Trusted criminals: white collar crime in contemporary society, 3rd edn. Thomson Wadsworth, Belmont

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

- Human Rights Watch (2009) “Wild Money”. The human rights consequences of illegal logging and corruption in Indonesia’s forestry sector. http://www.hrw.org/ sites/default/files/reports/indonesia1209webwcover. pdf. Accessed 30 Jan 2013

- Independent Inquiry Committee into the United Nations Oil-for-Food Programme (2005) Report on programme manipulation: chapter three – humanitarian goods transactions and illicit payments. http:// www.iic-offp.org. Accessed 8 Aug 2011

- Klitgaard R (1998) ‘International cooperation against corruption’ finance and development. Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/1998/03/ pdf/klitgaar.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2011

- Kramer RC, Michalowski RJ (2006) The original formulation. In: Michalowksi RJ, Kramer RC (eds) State-corporate crime. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

- Matza D, Sykes G (1961) Juvenile delinquency and subterranean values. Am Sociol Rev 26(5):712–719

- Nelken D (2007) White collar and corporate srime. In: Maguire M, Morgan R, Reiner R (eds) (2009) The Oxford handbook of criminology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Nye JS (1967) Corruption and political development: a cost-benefit analysis. Am Polit Sci Rev 61(2):417–427

- OECD (1997) Convention On Combating Bribery Of Foreign Public Officials In International Business Transactions. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/ dataoecd/4/18/38028044.pdf

- OECD (2008) Corruption. A glossary of international standards in criminal law. OECD, Paris, Accessed at www.oecd.org/dataoecd/59/38/41194428.pdf

- OECD (2011) OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises: recommendations for responsible business conduct in a global context. OECD, Paris

- Punch M (1996) Dirty business: exploring corporate misconduct. Sage, London

- Reiss A (1984) Consequences of compliance and deterrence models of law enforcement for the exercise of police discretion. Law Contemp Probl 47(4):83–122

- Schrager LS, Short JF (1977) Towards a sociology of organisational crime. Soc Probl 25:407–419

- Shover N, Hochstetler A (2006) Choosing white-collar crime. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) (2011) Armaments, disarmament and international security. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Slapper G, Tombs S (1999) Corporate crime. Longman, London

- Smart A, Hsu CL (2007) Corruption or social capital? Tact and the performance of Guanxi in market socialist China. In: Nuijten M, Anders G (eds) Corruption and the secret of law. Ashgate, Farnham

- Steffensmeier D (1989) On the causes of “white collar” crime: an assessment of Hirschi and Gottfredson’s claims. Criminology 27(2):345–358

- Tarnoff C (2009) Iraq: reconstruction assistance. Congressional Research Service, Washington

- UNDP (2010) Staying on track: tackling corruption risks in climate change. UNDP, New York

- Williams R (2000) Introduction. In: Williams R (ed) Explaining corruption. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

- World Health Organisation (2009) Medicines: corruption and pharmaceuticals. Fact sheet N 335. Accessed at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs335

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.