This sample Triads and Tongs Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The ancestor of Chinese triad society is Hung Mun, which was originally a loyal and righteous society. It was a secret society whose members, bound by oaths of blood brotherhood, were pledged to restore the ancient Empire, the Chinese Ming Dynasty, to the throne by overthrowing the foreign conqueror, the Munchow Qing Dynasty. Being a massive and highly coordinated political and military organization, it had a clear structure of commanders, officers, rank and file, and followers. Its members were all brave heroes rather than groups of criminals or vandals. Since China became a Republic in 1911, such loyal and patriotic nature had gradually diminished, leading to the disintegration of Hung Mun into dozens of separate triad societies engaging in criminal activities. The political turmoil in China between the two world wars, including the Japanese invasion and the rise of the Communist Party, forced the triads to retreat into Hong Kong. In 1960, the then Police Commissioner of Hong Kong made such a remark, “Of the approximately 3,000,000 inhabitants of Hong Kong it is estimated that about one in six is a triad member” (Morgan 1960:ix). Hong Kong is undoubtedly the capital of triad societies, which serves as the best venue for the study of triad structure, subculture, and transformation. Today, triads are criminal organizations acting independently of each other and use triad names and rituals for their own benefit. Although they are not as powerful as before, the problem still exists and the heroic figures presented by triad members in movies and cartoons have won the heart of working class youth (Lo 2012a).

Fundamentals

Organizational Structure

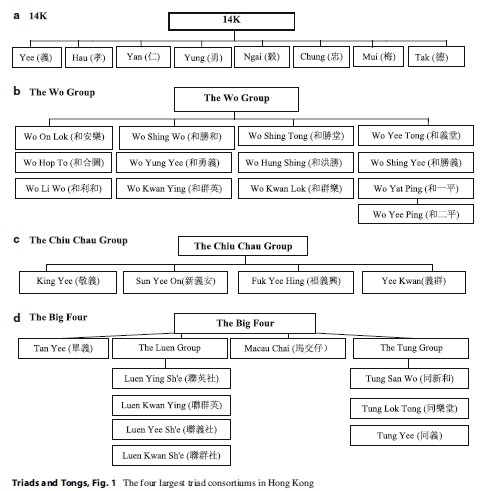

The triads in Hong Kong were originally affiliated to four large triad consortiums (see Fig. 1). Take the Wo group, one of the largest and oldest triad consortiums, as an example. It was formed by many triad societies, such as Wo Shing Wo, Wo Shing Yee, and Wo On Lok. The 14K was formed by such branches as Yee, Hau, Yan, and Yung (Cheung 1987). Their internal structure was characterized by a parent and branch relationship. Each triad society was controlled by an administrative headquarters whose authority extended to the branches and subbranches formed from them. As one of the functions of the headquarters was arbitration when interbranch or inter-society warfare occurred, the office bearers appointed to the headquarters were usually senior officers of various branches whose standing could command a measure of respect and influences onto other members.

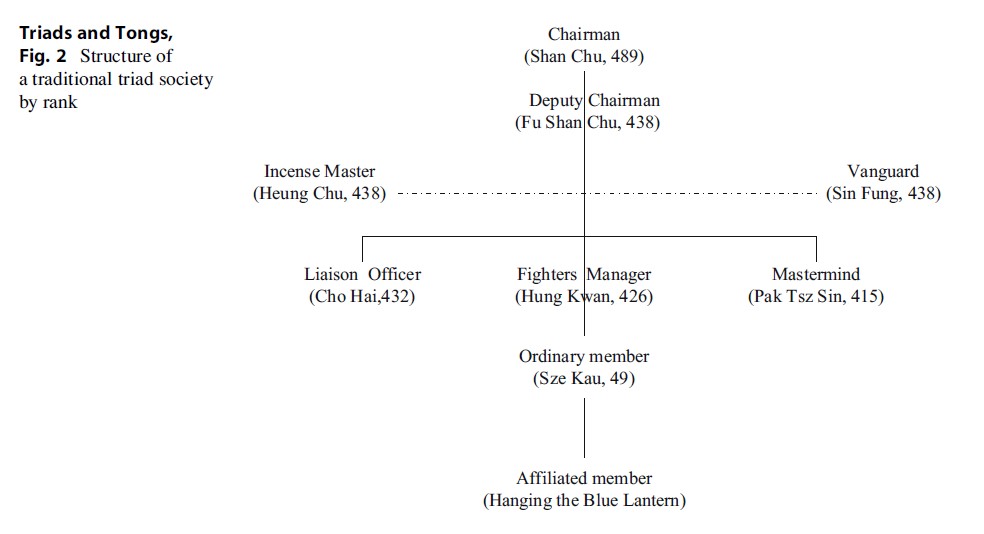

Traditionally, triad activities were facilitated by an established organizational structure (Fig. 2). The chairman of a triad society was known as Shan Chu (secret triad code 489), who was assisted by the Deputy Shan Chu (438) and had the authority in making final decisions in all matters relating to the triad. Assisting him were two officers of equal standing, Heung Chu (Incense Master, 438) and Sin Fung (Vanguard, 438), who had seniority in ranking and age. Their duties were to hold initiation and promotion ceremonies as well as recruitment and expansion of the triad (Morgan 1960). On the middle-level were three officers: Hung Kwan (426), Pak Tsz Sin (415), and Cho Hai (432). Hung Kwan in Chinese means “red pole,” signifying a weapon used in fighting. This officer is well-trained in Chinese martial art or tough and brave in fighting. He is the leader of fighters during triad warfare and also responsible for inflicting punishment on traitors. Pak Tsz Sin in Chinese means “white paper fan,” usually used by ancient Chinese intellectuals. This officer is the mastermind of the triad and normally appointed from among the most intellectual and educated members. His role is an adviser, thinker and planner. Cho Hai in Chinese means “straw sandal” which was frequently used by messengers and travelers of ancient time. Being the liaison officer of the triad, he becomes the intermediary between the headquarters and its branches. At the bottom of the hierarchy is Sze Kau (49) or ordinary members (Morgan 1960). Under the Sze Kau, there is a group of affiliated members called Hanging the Blue Lantern. The former has undergone a formal initiation ceremony in order to become a formal triad member (Sze Kau), while the Blue Lantern has not. But both of them are now used to identify generally triad members of the lowest rank.

In postwar decades, triad societies had undergone organizational transformation. The headquarters had no control over branches and procedures on promotion and recruitment had not been adhered to. Incidents of internal conflict always emerged. As time passed, the four large triad consortiums outlined in Fig. 1 dissolved. The triad societies were highly autonomous and used their own triad titles in the underworld. Some large triads have their own central committee to take care of their sub-branches and staff promotion. Some of the triads became inactive or faded out (e.g., Wo Yat Ping, Wo Yee Ping, Wo Kwan Ying), while some new criminal gangs emerged. A study in 2002 (Lo and Kwok 2012) confirmed that the following triads existed in Hong Kong:

- 14K – Hau, Tak, and others

- The Wo Group – Wo On Lok (Shui Fong), Wo Hop To, Wo Shing Wo, Wo Shing Yee, Wo Yee Tong, and Wo Kwan Lok

- The Chiu Chau Group – Sun Yee On, Fuk Yee Hing, and Hwok Lo.

- The Big Four – Tan Yee, Luen Kung Lok, Luen Ying Sh’e, Chuen Yat Chi, Lo Tung, Li Kwan, and Lo Wing

- Gangs emerged in the 1990s – Big Circle Gang and Hunan Gang

Following the disorganization of traditional triad structure, some triads adopted a more flexible hierarchical structure. Some ranks such as Shan Chu, Sin Fung, and Cho Hai became inactive. Pak Tsz Sin has also lost its popularity (Chu 2000). Yu (1998) interviewed triad officers and members in jail and found that 14K had already discarded the rank of Cho Hai. The ranks in existence today are Hung Kwan, Sze Kau, and Hanging the Blue Lantern (Chu 2000).

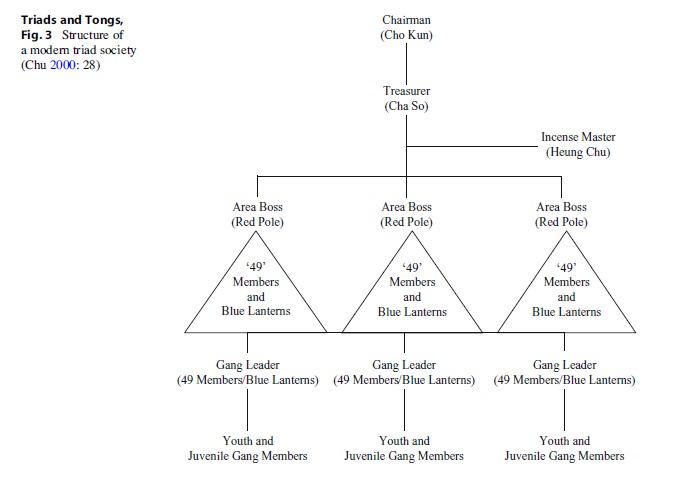

These three ranks are still widely used in modern triads. The headquarters is turned into a central committee and much simplified, composing of Cho Kun (chairman), Cha So (treasurer), and probably Heung Chu (Incense Master), usually elected among triad officers (Fig. 3). Taking the leadership role in the triad, this central committee has the authority to control promotion, enforce discipline, and settle disputes, but it often does not assign illegal activities to its members. In fact, the leaders in the central committee do not get any bonus from the activities that members engage in. Rather, the leaders only obtain money from occasions such as Chinese New Year, initiation ceremonies, and promotions, in the form of “red packets” (lucky money) (Chu 2000). However, the reputation of being a Cho Kun of an active triad in Hong Kong would help solicit both licit and illicit business opportunities in mainland China and overseas countries.

Another part of a triad is the mid-level area-focused sub-branches led by Hung Kwans (Red Pole) and followed by Sze Kau members and Blue Lanterns (Fig. 3). The gangs are organized by area and occasionally if the area is large enough, one or more gangs may occupy the same area but under different area bosses. They engage in criminal activities on the street level and their influences are extended to local youth gangs by means of a “Dai Lo–Lan Tsai” (Big Brother–Follower) relationship (Lo 2012a). This line represents a type of fictive kinship between them. The Dai Lo is normally a Hung Kwan or Sze Kau, who commands a triad located in the area. Under this relationship, a Lan Tsai becomes a Blue Lantern and can seek protection from his Dai Lo. He can claim the name of Dai Lo and the triad he belongs to during a conflict with another gang. On the other hand, the Dai Lo has the right to order the Lan Tsai to perform any tasks for him. The Blue Lantern (affiliated member) can become a Sze Kau (formal member) if he has accumulated sufficient criminal experience and attended an initiation ceremony. Through this “Dai Lo–Lan Tsai” relationship, a process of triadization (Lo 2012a) occurs whereby the youth gang members assimilate triad subculture and learn crime techniques from their seniors.

In addition to the above organizational structure, different triads have their own uniqueness. For instance, Sun Yee On, the most cohesive triad in Hong Kong, adopts a hereditary system in leadership succession and is managed by the “Heung” family. The 14K, the largest triad in terms of the number of members, is a loosely organized society, consisting of different street gangs under the control of their own area bosses who cooperate with one another on an ad hoc basis even though they share the same triad name. Wo On Lok, one of the powerful triads in the Wo Group, is still managed by a central committee, which controls promotions, supervises internal discipline, and settles internal and external disputes. It is led by a Cho Kun (chairman) and Cha So (treasurer), who are elected at biennial meetings. The chairman and committee officers are usually the most influential or wealthiest office bearers of the 426 rank (Chu 2000).

Rituals And Subcultural Values

Triad subcultural values include loyalty to the gang, eye for an eye, secrecy, and sworn brotherhood (Booth 1990; Morgan 1960). Triad members are required to regard themselves as one family and blood brothers; they are expected not to do harm to their brothers even under untoward circumstances and to sacrifice themselves for their group (Chin 1990; Lo 1984). There are rules, rituals, oaths, codes of conduct, and chains of command, as well as rigid control over the behavior of triad members, who have to follow triad norms that reflect sworn brotherhood (Lo 1993):

- Don’t “cal dai” (過底, don’t join other triads).

- Don’t be a “yee ng tsai” (二五仔, no squealing against the triad).

- Don’t “po wong” (報皇, don’t report anything to the police).

- Don’t “ngau dai” (淆底, don’t be scared in committing crime).

- Don’t “tuk pui chek” (篤背脊, don’t spread disadvantageous information against other triad brothers behind their back).

- Do obey Dai Lo.

- Do “bong tall” (幫拖, help triad brothers in fighting).

- Do “chow kei” (籌旗, give financial help to other triad brothers in times of trouble).

- Do “fuk cheuk” (覆桌, take revenge if the triad was attacked by rivals).

The essence of sworn brotherhood is also reflected in the triad initiation ceremony. Chu (2000: 32) highlighted 18 steps commonly used in the ceremony: “(1) tapping the new recruit’s left shoulder, (2) dashing the joss stick, (3) covering with the yellow gauze quilt, (4) passing through the Heaven and Earth ring, (5) passing through the fiery pit, (6) passing the two plank bridge, (7) eating the five seasonal fruit, (8) drinking the three river water, (9) smashing the bowl, (10) chopping off the chicken’s head, (11) pricking the middle finger of the left hand, (12) drinking the Read Flower wine, (13) eight-step worshipping in front of the altar, (14) old and new members bowing to each other, (15) washing the face of new recruits, (16) teaching triad hand signs, (17) bowing to the officer-bearers, and (18) giving lucky money to protectors.” All these rituals carry special meanings. The first eight steps highlight the process of entering into the Hung Mun and worshipping its ancestors, signifying the new recruits are going to join the triad concerned like their ancestors. Steps 9 and 10 emphasize that traitors will be punished with death. Steps 11–14 indicate blood brotherhood in the triad, signifying that after the members drink the wine that mix with the blood dripped from their fingers, they become blood brothers. Steps 15 and 16 signify that the new members will start a new life and learn the triad ways of communication. In the last two steps, 17 and 18, the new members thank their Dai Lo for recruiting and protecting them to round up the initiation ceremony.

In recent decades, there have been radical changes in the ideology and aims from those of traditional triads. Rituals and initiation ceremonies have been greatly simplified or even abandoned in order to avoid police targeting (Bolton et al. 1996). There has been a decrease in the use of hand signs and poems as secret methods of communication (Morgan 1960). The traditional triad principles of brotherhood and loyalty have more or less disappeared or modified, depending largely on particular Dai Lo’s interpretations of them. Members’ loyalty and righteousness have begun to diminish. The triads are no longer cohesive as the senior triad officers fail to control the middle and lower ranks, and conflicts between branches of the same triad often occur (Chu 2005). Moreover, triad members can cooperate with members of other triads to pursue their own financial goals if opportunities arise, which was previously regarded as a taboo.

There are several reasons for the gradual disorganization. The long chain of command and hierarchical structure increases the risk of exposure of triad activities. As triads are moving towards entrepreneurship, members from different triads, or triad members and ordinary businessmen, could work together to achieve the same moneymaking ends, while triad brotherhood is a less-valued subcultural element nowadays. Benefits and profits become a drive for bonding criminal partners instead of emphasis on brotherhood, which make triad rituals and values less appealing. In addition, the rituals of triads could be used as evidence in the prosecution of triad-related offenses (Kwok and Lo 2013). Consequently, the rituals do not help in smoothing operation but pose a risk to the triad. In view of the government’s increased control of triad activities and fast changing social environment, triads have to be flexible in their operational strategies and responsive to market demands and social conditions (Broadhurst and Lee 2009).

Triad Territory And Crime

Territoriality is a key element of triad organized crime. Even today, different triad societies have their own turf or monopolize certain economic sectors, without interfering with one another. They extort or provide protection services to shops, restaurants, hawkers, construction sites, wholesale and retail markets, bars, karaoke, and nightclubs which are located inside their territories (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). Clashes and violence occur when rival triads cross the line and step into their territory (Lo and Kwok 2012). Triads also operate different kinds of lucrative illicit trades, including but not limited to prostitution, pornography, soccer and other forms of gambling, human, cigarette and fuel smuggling, selling of counterfeit products, drug dealing and trafficking, and loan sharking (Broadhurst and Lee 2009; Curtis et al. 2002).

In addition to conventional criminal activities, some triads also engage in other forms of legitimate business, such as monopolizing the home decoration services in some housing estates, film and entertainment industry, car valet services, waste disposal industry, mahjong parlors, and nonfranchised minibus routes (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). Since the 1990s, triads have been found involving in insider trading and financial crime. Lo (2010) reported such a crime committed by the powerful Sun Yee On triad in collaboration with a Hong Kong listed company. The Sun Yee On leader and his associates used the privileged business information they “manufactured” in mainland China to drive the stock market crazy so as to obtain huge financial gain through insider trading and market manipulation.

International Perspectives

Mainlandization And Patriotic Triads

Since the 1990s, Hong Kong has experienced a process of mainlandization of its political, economic, and legal systems (Lo 2012b). Triads have also gone through a similar process of mainlandization as a result of China’s economic growth and rising demand for limited goods and services. Mainlandization is defined here as a process of making Hong Kong triads more reliant on mainland China for financial gain through social networking with Chinese officials, enterprises, and criminal syndicates and taking advantage of the rising legitimate and illegitimate business opportunities. In view of increasing licit and illicit opportunities in the mainland (the pull factor), triads have gradually shifted their moneymaking focus on China. The traditional triad rituals are now replaced by a business approach to crime. Chu (2000, 2005) observed that triads have increasingly invested in legitimate businesses and teamed up with entrepreneurs to monopolize the newly developed mainland market. In the illegal side, triads have also forged cooperative relationships with mainland criminal groups, trying to capitalize in the booming underworld (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). They provide their Chinese counterparts with crime techniques and intelligence, in return for cheap labor, sex workers and dangerous drugs to be consumed in Hong Kong.

In 1992, Tao Siju, the Minister of Public Security of China, remarked that some triad members were patriots. Tao even suggested that Deng Xiaoping had made a similar remark back in the 1980s because the triads protected him during his visit to the USA in 1979 (Arsovska and Craig 2006: note 127; Liu 2001). In 1993, Ye Xuanping, the vice-chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, was seen officiating in a mainland film production center owned by the Sun Yee On triad, with two of its leaders, Jimmy and Charles Heung, standing beside Ye (see Picture 1 in Lo 2010). The National Committee is one of China’s highest political bodies, and the presence of its vice-chairman in such an event confirmed the “united front” tactic frequently used by the Chinese Communist Party to incorporate opinion deviants into the establishment.

The Chinese national leaders applied the united front tactic on Sun Yee On to serve three political functions (Lo 2010). First, it was to close the Yellow Bird Action in which over 150 prodemocracy leaders and student activists were smuggled out of China with the assistance provided by Hong Kong triads after the Tiananmen crackdown on democratic movement in Beijing in 1989. Second, it was to uphold Hong Kong’s law and order in the run-up to 1997 when the people doubted whether “one country, two systems” would work and whether the rule of law would be upheld after China’s takeover of Hong Kong in 1997. The Chinese government was also concerned with the threats of the triads to Hong Kong’s social order, and thus the united front tactic was applied to recruit them to its side. Third, it was to prevent the infiltration of Taiwanese secret societies (e.g., the Bamboo United) into Hong Kong because of Taiwan’s model of heijin zhengzhi (or black-gold politics), where criminal gangs (black) join hands with businessmen (gold) to penetrate into the political arena and obtain power through local elections (Chin 2003). If the Chinese leaders aimed to maintain political control in Hong Kong after 1997, they could not allow prodemocratic forces in Hong Kong to join hands with any Taiwanese forces to take part in the elections.

In order to control Hong Kong’s political arena and social stability, China had to ensure that the most powerful triads were friends not enemies. Consequently, the triad leaders were included into the establishment by the label of patriotic triads and simultaneously performed some law and order functions for the communist state in exchange for business opportunities. Thus, triads played the roles of both angel and devil (Lo 2010). On the one hand, they served national interest and complemented established political and social structures. On the other hand, triad leaders used this label as a passport to expand its business network with mainland enterprises and criminal groups to further their interests, posing serious threats to the legal order.

Tong

Traditionally, a tong (堂) was a place for Chinese people with the same ethnicity, trade or industry to assemble for social interaction and recreational activities, settle interpersonal disputes, and gain mutual assistance and support from each other. In every village of China, there was a “che tong” (祠堂) which serves the above functions. In Hong Kong, “tong hau” (堂口) is constantly used to describe triad societies, such that “which “tong hau” one belongs to” is used to ask “which triad one is affiliated with.” In fact, some triads have the word “tong” in their name, such as Wo Shing Tong, Wo Yee Tong, Tung Yee Tong, and Tung Lok Tong. Chu (2000:19) contended that “numerous triad societies were set up simply because their original members were victimized by triads. In about 1910 the Tung Lok Tong triad society was established by coolies of the government hospitals in the Western District in order to protect the coolies against extortion by members of the Wo group.. ..The Wo Yee Tong triad society was founded in 1940 in Kennedy Town area of Hong Kong Island. It originally consisted of hawkers and stall-holders who banded together in defense against exploitation by triads.”

Tongs also exist in Chinatowns of the UK. For instance, the “Zhi Gong Tong Chinese Association (UK)” was found in Liverpool in July 2012, with the following introduction printed on a street board at the entrance of Chinatown: “The Origin of the Association had a strong link with Dr Sun Yat-sen, often referred to as the “father of modern China,” it supported the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. The association has branches across the continents. The association in the UK was set up to unite overseas Chinese and provide support to each other. It is one of the oldest Chinese community organizations in Liverpool. The association organizes transport for their members to the Everton and Anfield cemeteries twice a year to pay respect to Chinese ancestors, including those who had no family in the UK.” The above introduction indicates that tongs were patriotic, welfare and mutualhelp organizations that were active in Europe as early as the beginning of the twentieth century.

In the USA, tongs appeared in the Chinatown of San Francisco as early as the 1850s. The US Chinatowns had the characteristics of transitional zone, such as poverty and heterogeneous cultural background among residents. The local governments failed to provide effective social services to assist Chinese immigrants. Due to the lack of formal social services and resources within the towns, the tongs became the only self-help organizations that provided assistance and welfare, such as job referral, housing, networking and entertainment activities, to this group of socially excluded Chinese. They also acted as mediators in individual and group conflicts within the Chinese communities, as well as liaison between local government agencies and Chinese citizens in the constituencies (Chin 1990). Over the years, the power of tongs grew rapidly due to the constant social exclusion of Chinese immigrants and unrestricted recruitment of members. In recent decades, the tongs have been transformed from social service providers and self-defense organizations to illegal service providers. Their victims are mainly Chinese immigrants who have language and cultural barriers, thus being alienated from the mainstream society (Chin 1990, 1996).

Within each tong, there are many factions. Although there is a headquarters above these factions, it has no actual power over them. Most tongs have an elected president, but he only serves as a puppet controlled by the powerful officers and members in the headquarters, which consists of the president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer and auditor, and several public relations officers (Chin 1990). Ordinary members have to pay fees regularly, but they are not involved in any daily affairs and have no decision making power.

It has been argued that Chinese street gangs are affiliated with tongs. They provide protection services for tongs’ gambling business (Chin 1990, 1996; Chin et al. 1998; Curtis et al. 2002; Kelly et al. 1993). However, the relationship between tongs and gangs are complicated and indistinguishable. For example, tongs’ elders are involved in resolving conflicts between cliques within the gangs. Being the mentors of gang members, they transmit triad subculture and values to them and provide financial support and recreational venues. Their relationship is intertwined as some gang leaders are officially recruited into tongs, thus having dual membership. Some also introduce their followers into tongs. As a result, the elders of tongs can control gang members indirectly through the gang leaders, who serve as a broker between the tong elders and the street soldiers (Chin 1990). In addition, tongs also support street gangs through other means. For example, the tongs’ youth activity coordinators serve as the middlemen between tongs and gangs, sponsoring the sports activities of youth members of the tongs, including gang members. Tongs also provide job opportunities for the youth in their gambling houses, and offer financial compensation to gang members or relocate them to other cities when they are in trouble.

Despite such close relationships, mistrust and misunderstanding between the two parties are rampant. Many tongs use the gangs as a tool to commit crime so that they can be insulated from the criminal activities, but they do not truly regard the gangs as part of the organization. On the other hand, some gangs do not want to be controlled by tongs. They do not feel compelled to follow the command of tongs and want to be independent (Chin 1990). Therefore, the relationship between tongs and street gangs is never static and monolithic.

Tongs differ from triads. Triads are illegal organizations, but tongs are legal entities although they consist of both law abiding and law breaking members and provide both licit and illicit services to the Chinese communities. With their original goals of self-protection and mutual assistance, tongs were not established exclusively for criminal activities. As such, law enforcement agencies tend to chase after individual criminals of the tongs rather than the tongs. Therefore, even if the criminals are arrested, the tongs will still survive and recruit new blood to replace the caught members (Zhang 2012).

Triads, Tongs, And Transnational Organized Crime

Before China resumed the sovereignty of Hong Kong in 1997, there was serious concern that the communist takeover would lead to a mass exodus of Hong Kong triads to the West (Kenney and Finckenauer 1995). However, Lo (1995) argued that due to the increase of both licit and illicit business opportunities in mainland China, the possibility of such exodus was slim; rather, it was the internationalization of triad activities that should be of major concern to the western nations. Reports from Southeast Asia, North America, and the UK revealed that triad organized crimes, such as drug trafficking and human smuggling, were on the rise in these jurisdictions (Curtis et al. 2002). Since some individual triad members migrated overseas in fear of the communist rule, they become Hong Kong triads’ overseas trustful partners. They possess the necessary skills, experiences and triad values. Therefore, criminal partners at the two ends of the international servicing channel collaborate with each other, sharing the same goal, subculture, and norms.

Zhang and Chin (2003) argue that the traditional structure of triads facilitate them to commit crime in local territories but hinder their involvement in transnational criminal activities. Despite the increasing number of reports indicating triads’ or tongs’ involvement in transnational organized crime, such as human smuggling and narcotics trafficking (Curtis et al. 2003), the findings remain inconclusive, and the role of triads and tongs in transnational crime is still unclear. There is no credible evidence to prove their collective involvement in narcotic trafficking (Chin 1996). Empirical research found the involvement of triads and tongs in smuggling is only restricted to individual members and operated in a disorganized basis (Zhang 2007). It was observed that many heroin trafficking and smuggling cases were conducted in dynamic form involving multi-criminal groups, legitimate business, and other social sectors, rather than monopolized by a single triad or tong (Chin and Zhang 2007; Zhang and Chin 2003; Zhang 2007).

Zhang and Chin (2003)’s structural deficiency perspective shed light on the reason why triads and tongs, being territorial-based criminal organizations, fail to expand their operations into the arena of transnational organized crime. Their hierarchical structure, preservation of continuity and group identity, restricted membership, monopolization in activities, and preferring long-term and low-risk benefit from illicit operations do not fit with the structural requirements of transnational organized crime (Zhang 2012). Both smuggling and trafficking markets are fluid and multifaceted due to the extensive movement involved in illicit goods and services. The markets of transnational crime are fragmented, risky, and uncertain because the clientele are scattered over different regions, and the crime is exposed to law enforcement agencies of different nations. Therefore, transnational organized crimes are best operated by loosely organized ad hoc groups rather than hierarchical organizations like the triads and tongs, because small-sized groups could be more adaptable and responsive to the unstable and hostile environment. The risky smuggling and trafficking environment requires limited vertical hierarchy with high level of division of labor, instead of bulky, hierarchical structure with long reporting line.

Moreover, due to the liberalization of the smuggling and narcotic trafficking market, the illicit market is open to anyone with resources, social capital, and access to business opportunities. Consequently, it is difficult for one particular group to dominate the market and the long-term stable benefit is not guaranteed. Therefore, it may not fit with the organizational goal of triads and tongs. In addition, flexibility in recruitment is important for transnational crime operation, as the clientele is limited and the opportunities are not constantly available. The restricted membership system and identity of triads and tongs reduce flexibility in developing new network and grasping new opportunities, making them difficult to compete with freelance participants who now share the illicit transnational market (Zhang and Chin 2003).

Future Directions

Given the rapid economic development and rising interest of overseas investors, triads are taking a stake in the Chinese market. Mainlandization is the characteristic of triad crime in the new century. A possible analogy of mainlandization is a “vacuum cleaner.” Once the hover starts, the current is so strong that everything will be sucked into it. Triads are pulled into mainland China because of the lucrative profit and low risk. Economic prosperity in the mainland provides ample opportunities for the triads to generate profit, whereas the risk is low due to the power monopoly and corruptibility of judicial, municipal and police officials, the absence of the rule of law, a weak civic society and censored mass media, and the existence of guanxi and protective umbrella where criminal syndicates can bribe officials in exchange for protection in their activities (Zhang and Chin 2008). Such economic and political climate encourages triads to leave their local territories to embrace the “patriotic triad” claim in the mainland (Lo 2010; Lo and Kwok 2012).

The unknowns ahead, however, are whether the triads can secure their position in the mainland. Does mainlandization take place simply in the form of crime displacement? Can triads trans plant their illegal operations from Hong Kong to the mainland? Can Hong Kong triads colonize the underworld of the mainland? Will transplantation and colonization (Varese 2006) elicit resistance from mainland criminal syndicates against Hong Kong triads? On the mainland, the Chinese government has been aware of the potential risk of triad displacement or transplantation to the mainland. In order to control this trend, the government amended its Criminal Law in 2002 and Article 294 stipulates that triad members outside China trying to recruit members or develop a triad branch in China will be sentenced to 3–10 years of imprisonment. The government has paid close scrutiny to the development of “triad-nature” crime and activities, but how effective the law, procuratorate, and public security organs are in controlling triads in the mainland is a major concern. All of the aforementioned questions need to be further addressed and require more research.

Bibliography:

- Arsovska J, Craig M (2006) Honourable behaviour and the conceptualisation of violence in ethnic-based organized crime groups: an examination of the Albanian Kanun and the code of the Chinese triads. Global Crime 7(2):214–246

- Bolton K, Hutton C, Ip P (1996) The speech-act offence: claiming and professing membership of a triad society in Hong Kong. Lang Commun 16:263–290

- Booth M (1990) The triads: the Chinese criminal fraternity. Grafton Books, London

- Broadhurst R, Lee KW (2009) The transformation of triad ‘dark societies’ in Hong Kong: the impact of law enforcement, socio-economic and political change. Secur Chall 5(4):1–38

- Cheung S (1987) The activities of triad societies in Hong Kong. Cosmo Books, Hong Kong

- Chin K (1990) Chinese subculture and criminality: nontraditional crime group in America. Greenwood, Westport

- Chin K (1996) Chinatown gangs: extortion, enterprise, and ethnicity. Oxford University Press, New York

- Chin K (2003) Heijin: organized crime, business, and politics in Taiwan. M.E. Sharpe, NY

- Chin K, Zhang SX (2007) The Chinese connection: cross-border drug trafficking between Myanmar and China. Final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice for Grant #2004-IJ-CX-0023. Rutgers University, Newark

- Chin K, Zhang SX, Kelly R (1998) Transnational Chinese organized crime activities. Transnatl Organ Crime 4(3/4):127–154

- Chu YK (2000) The triads as business. Routledge, London

- Chu YK (2005) Hong Kong triads after 1997. Trends Organ Crime 8(3):5–12

- Curtis EG, Elan SL, Hudson RA, Kollars NA (2002) Transnational activities of Chinese crime organizations. Trends Organ Crime 7(3):19–59

- Curtis GE, Elan S, Hudson R, Kollars N (2003) Transnational activities of Chinese crime organizations. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/pdf-files/ ChineseOrgCrime.pdf. Accessed 30 Sept 2012

- Dombrink J, Song JHL (1996) Hong Kong after 1997: transnational organized crime in a shrinking world. J Contemp Crim Justice 12(4):329–339

- Kelly R, Chin K, Fagan J (1993) Structure, activity, and control of Chinese gangs: law enforcement perspectives. J Contemp Crim Justice 9(3):221–239

- Kenney DJ, Finckenauer JO (1995) Organized crime in America. Wadsworth, San Francisco

- Kwok SI, Lo TW (2013) Anti-triad legislations in Hong Kong: issues, problems and development. Trends Organ Crime 16:74–94

- Liu B (2001) The Hong Kong triad societies before and after the 1997 change-over. Net e-Publishing, Hong Kong

- Lo TW (1984) Gang dynamics. Caritas, Hong Kong

- Lo TW (1993) Neutralization of group control in youth gangs. Groupwork 6(1):51–63

- Lo TW (1995) Patriotic triads and the 1997 exodus, paper presented in the conference on Hong Kong and its Pearl River Delta Hinterland: links to China, links to the world. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 4–6 May 1995

- Lo TW (2010) Beyond social capital: triad organized crime in Hong Kong and China. Br J Criminol 50:851–872

- Lo TW (2012a) Triadization of youth gangs in Hong Kong. Br J Criminol 52:556–576

- Lo TW (2012b) Resistance to the mainlandization of criminal justice practices: a barrier to the development of restorative justice in Hong Kong. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 56(4):627–645

- Lo TW, Kwok SI (2012) Traditional organized crime in the modern world: how triad societies respond to socioeconomic change. In: Siegel D, van de Bunt H (eds) Traditional organized crime in the modern world: responses to Socioeconomic change, vol 11, Studies of organized crime. Springer, New York, pp 67–89

- Morgan WP (1960) Triad societies in Hong Kong. Government Printer, Hong Kong

- Varese F (2006) How Mafia’s migrate: the case of the Ndrangheta in northern Italy. Law Soc 40(2):411–444

- Yu KF (1998) The structure and subculture of triad societies in Hong Kong. City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

- Zhang S (2007) Smuggling and trafficking in human beings: all roads lead to America. Praeger/Greenwood, Westport

- Zhang S (2012) China tongs in America: continuity and opportunities. In: Siegel D, van de Bunt H (eds) Traditional organized crime in the modern world: responses to socioeconomic change, vol 11, Studies of organized crime. Springer, New York, pp 109–128

- Zhang S, Chin K (2003) The declining significance of triad societies in transnational illegal activities: a structural deficiency perspective. Br J Criminol 43:469–488

- Zhang S, Chin K (2008) Snakeheads, mules, and protective umbrellas: a review of current research on Chinese organized crime. Crime Law Soc Change 50:177–195

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.