This sample Use of Social Media in Policing Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Social media has in many ways altered the landscape of communication and information sharing in recent years. Nearly 750 million people across the globe are estimated to have accessed Facebook by August 2011, or nearly one-tenth of the world’s population (Facebook 2012). Its impact has been felt across the social landscape, from basic interpersonal communications to shaping the short-term and long-term sociopolitical future of some countries. It has been argued, for example, that it played a central role in the toppling of tyrannical governments during the “Arab Spring” of 2011 (Howard and Hussain 2011). With the breadth and depth of this impact in mind, law enforcement agencies have begun to adopt social media strategies in an effort to expand the scope of their communication strategies. It is estimated that by September 2011, approximately 88 % of law enforcement agencies across the United States had adopted some form of social media strategy (International Association of Chiefs of Police 2011). The purpose of this research paper is to provide an overview of the use of social media in law enforcement. After providing a definition and brief history of social media, the authors provide a conceptual framework for understanding the role of social media, like other mechanisms for communication and information sharing, within a policing environment. The paper then provides an overview of the benefits and potential liabilities associated with the integration of social media into organization communication strategies. Finally, the paper offers a set of policy recommendations that can assist police organizations considering implementing social media strategies.

Background

The City of Los Angeles was rocked by a series of fires that occurred between December 29, 2011 and January 2, 2012 when more than 50 separate instances of arson indiscriminately occurred. By December 31, it was clear that there was a serial arsonist on the loose wreaking havoc in the greater Los Angeles area. While motor vehicles were the primary targets, several fires quickly spread to nearby buildings, which only intensified the mounting problems. The damage was extensive in many situations as evidenced by one small cluster of fires in the West Hollywood area that caused more than $350,000 worth of damage to vehicles and property (CNN 2012).

Fire officials scrambled across the widely dispersed city in an effort to get a handle on the expanding threat. But with multiple fires erupting within short periods of time, the public safety capacity of Los Angeles was pushed to its limits. Public safety officials quickly turned to social media as an outlet to both collect quickly emerging information from the public about a rash of fires, but also to communicate back to the public about the evolving situation, particularly when a suspect was eventually identified. Almost immediately it was recognized that social media played a critical role in a quick resolution to this public safety crisis. It greatly enhanced the ability of public safety officials to disseminate information to the public and media alike quickly, but also because it provided a capacity to access segments of the community that might otherwise not frequent more conventional news outlets. In the end, a suspect was identified and apprehended by January 2, 2012. The police and traditional media have universally recognized the value of social media in helping to bring this situation to a timely end.

The 2011–2012 New Year’s fires represent an important milestone for the Los Angeles Police Department; the fires represented one of the first times that social media has been used by the LAPD in an effort to facilitate bi-directional communication with the public about an emerging public safety threat. This example shows the promise that social media presents to public safety officials trying to do more with less. Yet, while the potential advantages to implementing a robust social media capacity are apparent to many, some police departments across the United States have been reluctant to accept this new form of communication. While the reasons for this reluctance might be many, it is clear that at least some of this apprehension is due to basic lack of familiarity and expertise.

Social media is a complex concept that generally refers to a broad range of non-traditional forms of electronic communication. It is not completely clear what exactly the term “social media” encompasses. Social media ranges widely in form and purpose. According to Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), social media is “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content” (p. 61).

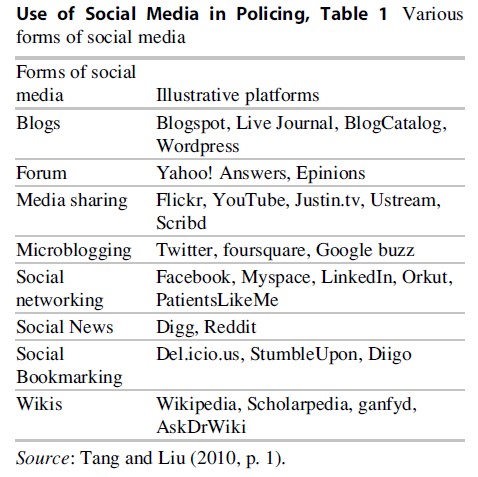

As of 2010, forms of social media included blogs and microblogs, discussion forums, media sharing websites, social networks, social news, social bookmarking, and Wikis (see Table 1). Although these forms of social media differ, a common feature that differentiates them from the conventional web and traditional media is that they are consumers of content. Compared to traditional media (TV, radio, movies, and newspapers), in which only a small number of people decide which information should be produced and how it is distributed, a user of social media can be both a consumer and a producer. With millions of users active on the various social media sites, everyone can be a media outlet. Thus, social media allows for the production of timely news and leads to volumes of usergenerated content.

Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) take on a slightly different approach when defining social media by developing a more robust classification scheme. According to the authors, there are six different types of social media. The first type of socialmedia is collaborative projects, which allow for the joint and simultaneous creation of content by end-users (e.g. Wikipedia). The second type of social media is blogs and micro-blogs, which are particular websites that normally display date-stamped entries in reverse chronological order (e.g. Twitter). Third, content communities refer to the sharing of media content between users (e.g. YouTube). The fourth type is social net- working sites, which allow users to connect by creating profiles, enabling friends to have access to those profiles, and sending emails and instant messages between each other (e.g. Facebook). The fifth type is virtual game worlds, which refers to platforms that portray a three dimensional environment whereby users can create and appear in the form of personalized avatars and interact with each other (e.g. World of Warcraft). Finally, virtual social worlds are similar to virtual game worlds, except there are no rules restricting the range of possible interactions, such as the Second Life application (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010). These technologies allow users to simply create content on the Internet and share it with others. Thus, social media is the infrastructure that enables users to become publishers of content that is interesting to them and others.

Social media allows for the production of timely news and information. For example, during the London terrorist attack in 2005, some witnesses blogged about their experience in order to provide first-hand reports of the incident. Similarly, witnesses provided updates on Twitter during the bloody clash that resulted from the Iranian presidential election in 2009. In the event of an emergency or disaster, people have demonstrated to turn to social media platforms. This has prompted the city of Arcadia, California to introduce social media to their Emergency Operations Center (LeVeque 2011). In addition, social media enables collaborative writing to create high-quality bodies of work that was not previously possible. For example, over the last decade, Wikipedia has grown into one of the largest reference web sites, with more than 85,000 active contributors working on more than 14,000,000 articles and attracting more than 65 million visitors monthly. Furthermore, one of social media’s unique characteristics is in its user interaction. The participation of users on social media websites is what makes them successful, advancing eight social media sites to the top 20 websites in the United States (Tang and Liu 2010).

Evolution Of Social Media

Because the term social media is not exactly clear, examining the history also varies from different sources. However, several articles agree that an early social media service was launched in 1997. According to Boyd and Ellison (2007), the first recognizable social network site, Sixdegrees.com, was launched in 1997, which allowed users to create profiles, list their friends, and, starting in 1998, view the “friends” list. In 1999, Pyra Labs’ Blogger was introduced, an early blog-publishing service that allows blogs with time-stamped entries (Paquet 2002). Another social media website created in 1999 included LiveJournal, a virtual community in which users can keep a blog. The next series of social networking sites began in 2001 when Ryze.com was created to allow people to leverage their business networks (Boyd and Ellison 2007).

According to Boyd and Ellison (2007), three key social networking sites that shaped the business, cultural, and research landscape included Friendster (2002), Myspace (2003), and Facebook (2004). Friendster was created in order to help friends-of-friends meet, unlike meeting strangers on dating websites. However, due to a substantial increase in users, the site encountered technical difficulties, leading to a reduction in the number of users. Social networking sites really hit the mainstream from 2003 onward. Most sites used a profile-centric form, similar to Frendster. Myspace was created in 2003 in order to compete with other social networking sites like Friendster and Xanga. Myspace differentiated itself from other social media sites because it allowed users to personalize their pages. A significant number of teenagers began joining Myspace in 2004, and eventually evolved into three distinct populations: musicians/artists, teenagers, and the post-college urban social crowd. Facebook was originally designed to support distinct college networks only. Although it started as a Harvard only site, it eventually expanded to include other colleges, high school students, professionals inside corporate networks, and, ultimately, everyone. The latest key social media site that has substantially increased in popularity over the last few years is Twitter. Twitter, which began in 2006, is a micro-blogging site, limiting posts to 140 characters or less. This restriction allows real-time posts, also known as “tweets,” to be made using short message service (SMS) technology, which is the basis for text messaging on cell phones and other mobile devices. Although these social media sites have been created and evolved to seek broad audiences, several sites also target business people, such as LinkedIn, Visible Path, and Xing. A recent study argues that LinkedIn is a fantastic tool for law enforcement professionals (Stevens 2011). Table 1 illustrates the evolution of major social networking sites. Because the history of social media encompasses a huge phenomenon, this list is unavoidably incomplete.

Explosion Of Social Media Use

In recent years, there has also been a considerable expansion in the levels of use of social media. According to Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), 75 % of Internet users used “social media” in the second quarter of 2008 by becoming members of social networks, reading blogs, or writing reviews on shopping websites, compared to 56 % in 2007. This growth is not only attributable to teenagers, but also populations well beyond their forties and fifties. According to Chou et al. (2009), participation in social networking sites more than quadrupled from 2005 to 2009. Boyd and Ellison (2007) claim that although there is not any exact data regarding how many people use social media websites, marketing research suggests that these sites are growing exponentially worldwide. As a result, many corporations now invest time and money into creating, purchasing, and promoting social networking sites. Boyd and Ellison (2007) also argue that the rise of social networking sites suggest a shift in the organization of online communities. Social networking sites are now mainly organized around people, not interests, and are structured around personal networks. Therefore, social media is an extremely active and evolving domain that now accounts for a significant proportion of Internet traffic.

A recent poll by the Pew Research Center indicates that approximately 66 % of online adults use social media, with the vast majority reporting the use social media to “stay connected” to family and friends (Smith 2011). Although the extent of connectivity via social media sites varies across countries, data indicate that approximately 30 % of adults in most industrialized countries use social media to some degree (Pew Research Center 2011). Facebook, one of the leading social media companies, has experienced an exponential increase in the number of registered users in recent years. The number of registered “active” users, for example, increased from 12 million in December 2006, to 100 million in August 2008, to 500 million in July 2010, and finally to over 750 million “active” users by August 2011 (Facebook 2012). This figure, which represents nearly 10 % of the world’s population, is nearly impossible to grasp. The magnitude and speed of this growth defies comprehension and has placed its founder, Mark Zuckerburg, as one of the wealthiest people in the world.. .at age 27 (Forbes 2012). The use of social media has affected the social landscape in many ways, and has added terms such as “friending,” “defriending,” and “tweets” into the daily lexicon of many.

The Legacy Of Technology In Policing: Setting The Stage For Social Media

It should come as no surprise that social media has developed into an issue that police departments across the world have sought to understand and harness. Policing is in many ways a technology driven profession that has historically been quick to adopt burgeoning forms of technology, particularly as it relates to communication and information sharing. The motorized vehicle, radio communication systems, and computer systems have been integrated into policing in highly visible and instrumental ways. The tendency toward the adoption of technology is functional and symbolic as well as practical and ceremonial. From the outside, it appears that police have enjoyed and exploited major technological advancements of the modern era (Brady 1997). As Varano et al. (2007, p. 263) argued, “technology [in policing] holds the symbolic potential for providing a degree of respect as it implies access to resources, commitment to innovation, organizational leadership, and a degree of sophistication.” That many police organizations have adopted social media as a way of communicating to the public, then, should be of little surprise.

Social media represents one of the next biggest waves of technological advancement in law enforcement. Like other governmental sector agencies, many police departments around the world have been quick to adopt the use of social media to communicate with the public. A recent survey by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (2011) found that 88 % of 800 surveyed agencies reported some use of social media, with Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube among the most common (p. 4). These strategies, in many ways, lie at heart of more innovative policing strategies such as community-policing or problem-oriented policing, both of which hold police-citizen communication/interaction as a core philosophy. The most common reasons cited by police for the adoption of social media include community outreach, information dissemination, emergency/ disaster notification, and investigations (International Association of Chiefs of Police 2011, p. 9). Not only do social media provide a greater opportunity for bi-directional communication with the public in general, it is even more so for the younger generation. Young people across the socioeconomic divide use social media to stay connected with family and friends, as a primary source of information about the world around them, and even as a primary source of emotional support (Ellison et al. 2007; Greenhow and Robelia 2009). There is a growing sense that while exploitation of social media might be optional today, it will not remain so for very long as these new forms of communication expand in their dominance of the social landscape and discourse.

Factors Underlying The Adoption Of Social Media Practices

From a conceptual point of view, the trend toward adoption and expansion of social media in policing is part of a larger trend centered on greater communication with the public. Community policing, a policing model that stresses community engagement and proactive problem-solving, has pushed police departments and communities alike to reorient themselves in ways that view one another more as allies and less as adversaries. Community policing represents an important paradigm shift that moves police out of the role of the crime fighting professional who is solely responsible for establishing organizational priorities. Instead, the community is viewed as an active participant in organizational processes. The community has a role in defining organizational priorities, but just as important, the police are held accountable to the public they police. Community policy sees the community as the customer whose needs are worthy of consideration. This is part of a lager “customer service” trend in the public sector.

Another important dimension of community policing has been the notion of police accountability to the public. That is, community policing is based on the premise that the community not only has a direct role in helping to shape organizational priorities, but that the police have a responsibility for sharing information with the public. It is important to remember that information sharing is not something that comes natural in policing environments. Information is generally something to be tightly controlled and it is disseminated on a “need to know” basis. Police are traditionally not in the habit of sharing information about individual cases or overall trends with the public. This, however, is not unique to the relationship between the police and the public. Most police departments are reluctant to share information with other police departments and even other units (e.g., vice, narcotics, or gang units) within the same police department. It is also not uncommon for officers in the same unit within the same department to be reluctant to share information with each other. The need to tightly control the internal and external flow of information is viewed as so important that many departments employ a “Public Information Officer” to specifically handle requests for information. Thus, information sharing is something that is neither natural nor routine in a policing environment.

From a conceptual point of view, information sharing can be viewed not only as a service to the public, but also as image control whereby police agencies have adopted deliberative strategies intended to create positive public presences. Driven both by the desire to share information and to craft an image of a progressive department, many agencies have some sort of presence on the World Wide Web. Social media then is likely part of this larger trend toward information sharing and community outreach.

While there is little doubt that the movement toward community policing partially explains the expansion of social media, it is not the exclusive factor. The movement toward a “virtual presence” on the web, including the adoption of social media, has also been influenced by resource constraints that have plagued policing and other public sector agencies, particularly in the past two decades. In policing, calls for service (e.g., 911 calls) are one of the primary sources of workload. Large call volumes to emergency 911 centers and shrinking personnel resources due to layoffs have put pressure on police departments to develop innovative ways to reduce workload, but to do so in a way that compromises neither public safety nor community relations. Police departments across the United States have experimented with alterative reporting strategies that have moved non-emergency calls out of the 911 system. The goal of these efforts is to free up officer patrol time by limiting their involvement in non-emergency events that do not need a police response. Moreover, the intent is to also enhance customer satisfaction by creating a reporting strategy that is more convenient. At the end of the day, alternative reporting systems are premised on leveraging existing resources in a way that maximizes return and enhances customer service.

Communities experimented with a variety of non-emergency reporting strategies including 311 systems and phone-based police reports. What few evaluations are published indicate that, by and large, alternative systems can be effective alternatives to the traditional 911 system (Mazerolle et al. 2003). The explosion of the internet, however, created a new and relatively inexpensive crime reporting strategy – online crime reporting. By the 1990s police departments across the United States were experimenting with the use of online crime reporting technologies as a means for permitting the reporting of crimes in a way most convenient to the victims. Since many departments were already developing an online presence as part of the community outreach efforts identified above, this seemed to be a natural extension of these efforts. While the actual prevalence of online reporting is unclear, the Executive Director of the COPS Office, Bernard Melekian, has referred to it as the “wave of the future” (Cisneros 2009).

It has been the movement toward community engagement and the impact of financial constraints requiring police to do more with less, phenomenon that occurred almost simultaneously, that set the stage for the adoption of social media. The ever-expanding capacity of internet, the diffusion of computer technology across most segments of society, and rapid expansion of evolution of social media all occurred within a short 10–15 year period. The quickly evolving technical infrastructure provided the means for police, like other public and private sector agencies, to develop a virtual presence and cautiously explore the dynamics of information sharing.

The Use Of Social Media In Policing

As social media continues to expand in its dominance of the social landscape, organizations in any profession that dismiss social media will find themselves lagging behind. Utilizing social media has several benefits and can be extremely invaluable in a contemporary policing environment. To keep up with the quickly evolving landscape, many police departments have experimented with different strategies. There remains, however, wide variation in the extent to which social media has been adopted within the policing community. Below is an overview of how social media has been integrated into policing.

Recruitment

Police recruitment in the twenty-first century can be especially challenging. Agencies are faced with staffing challenges associated with budget-related attrition, retiring wave associated with the baby-boom generation, and certain “generational trends” that move qualified candidates to other professions (Wilson and Castaneda 2011). In order to be competitive employers, law enforcement agencies need to be resourceful in their approach for recruiting applicants and seek new tools to accomplish this task. Social media offers law enforcement this new set of tools with an ability to attract, engage, and inform potential applicants.

There are several advantages of using social media platforms for recruitment volume. With the vast number of users who utilize social media sites on a daily basis, it presents a great opportunity to connect with both passive and active job seekers. Also, unlike commercials and paid investments, social media sites are inexpensive. For example, there is no cost to create an account, but personal time is necessary to maintain and update content on the sites. In addition, social media allows agencies to answer any recruitment questions applicants might have on a personal level and in a publicly accessible fashion (International Association of Chiefs of Police 2011).

Law enforcement agencies such as the Houston Police Department (Texas) and the Vancouver Police Department (British Columbia) currently use social media platforms including blogs, social networks, and multimedia-sharing sites to give potential applicants a unique and distinct view of the police profession. In 2008, a Houston Police Department senior officer launched a successful blog in order to provide insight and offer a resource to jobseekers, applicants, and new recruits. The blog consists of stories, information, videos, and pictures, with daily weekday posts. The recruitment blog substantially expanded, starting with approximately 15 hits per day to now over 1,500 site views daily. The Houston Police officer argues that it offers the ability to share insight with potential applicants that they cannot get anywhere else (International Association of Chiefs of Police n.d.-b). The Kentucky State Police has also turned to various social media platforms to attract new recruits. The agency has launched recruiting videos on its YouTube Channel, while already having presence on Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, and Blogger.com (Gazaway 2011).

Social media tools such as the methods used by the Houston Police Department and Kentucky State Police have offered law enforcement agencies the ability to connect with the general public and answer any questions about a future career in law enforcement. Blogs have given agencies a method to communicate more regularly and more personally than a conventional department website offers. For example, some topics discussed include a day in the life of a new recruit, advice or comments from the police chief, and miscellaneous blog posts from other department personnel. Law enforcement agencies have used Facebook to communicate with both potential and current applicants. Facebook posts allow applicants to have specific conversations that can be viewed by other applicants. In addition, departments have created a personal YouTube channel in order to post recruitment and other career-related videos.

Investigations

Social media is transforming the way in which law enforcement agencies conduct investigations and should be embraced by the department as a whole. Law enforcement agencies use social media for investigative purposes when seeking evidence or information about missing or wanted persons, gang participation, as well as Internet crimes such as cyberstalking or cyberbullying. For example, in Franklin, Indiana, police work with prosecutors and use social network sites as evidence in cases ranging from underage drinking to child custody cases. Information found online helps supplement other evidence already gathered by the police (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010). In one case, police and prosecutors convicted an individual of operating a vehicle under the influence of a controlled substance. The individual had smoked marijuana on the day he crashed his vehicle and killed another individual inside. On his Facebook page, the individual referenced his marijuana use and also posted photos of a bong (Michalos 2010). This example illustrates what many law enforcement agencies are doing throughout the country in which police and prosecutors are using information found on social media sites to gather and enhance the evidence against an individual (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010).

The Utica, New York Police Department (UPD) has been using Facebook since 2010 and began using Twitter and YouTube in 2011. During a period of 4 months, UPD made 11 arrests directly from information posted on the UPD social media sites, including a bank robbery and numerous grand larcenies. In some cases, people have turned themselves in, possibly out of fear or embarrassment. In other cases, people who recognize the pictures and videos contact the police department with information. The Department believes that social media empowers the community to get involved in the crime fighting process (International Association of Chiefs of Police, n.d.-a). This leads to enhanced relationships with community members.

Community Outreach And Citizen Engagement

Law enforcement agencies have begun to use social media tools to enhance community policing initiatives. Police departments throughout the country, for example, are posting crime prevention tips through various social media platforms, providing opportunities to report crime online, posting crime maps and other data, and disseminating alert information to the community (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010). Agencies throughout the country are also using social media platforms to reach out to their community members in order to foster better relationships and connections. For example, Baltimore Police Department uses social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Nixle to enhance their relationship with the community and increase knowledge and safety throughout the city. The Baltimore Police Department uses social media sites as “an extension of the local news media because the media can’t cover everything that happens and involves the department” (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010, p. 2). The Richmond (Virginia) Police Department (RPD) also uses social media sites to strengthen community relations. RPD posts information on their sites such as its “officer of the month” (Wagley 2011). The Colorado Springs Police Department (CSPD) uses social media sites and includes several features on its pages including: From the Chief, Quote of the Week, and Officer of the Month. The department argues that there is real value in sharing information with the public and illustrating how the different processes and procedures work within the police department. CSPD has received positive feedback from the community (International Association of Chiefs of Police n.d.).

In terms of citizen engagement, the Boca Raton (Florida) Police Department has clearly structured and defined goals regarding social media outreach. The department’s social media and communications strategies prioritize effectively engaging the community. Thus, instead of simply disseminating information to the public, the department’s social networking sites allow for two-way communication, which allow for heightened levels of transparency. The two-way communication also offers a mechanism for the police department to gather information from community members (Alexander 2011).

Background Investigations

Social media has also been used to screen potential police officers during the application phase. Much to the consternation of some, several law enforcement agencies request that applicants sign waivers that allow investigators to have access to their various social media sites in the search of disqualifying information. Some agencies even require candidates to provide private passwords, Internet pseudonyms, text messages, and email logs as part of the expanding cyber-vetting process for law enforcement jobs (Rose et al. 2010). According to a report on law enforcement social media use, more than a third of 728 law enforcement agencies check applicants’ social media sites during background checks. A potential recruit in Malden, Massachusetts was disqualified after background investigators found evidence of a past threat of suicide. Another potential candidate in Middletown, New Jersey was disqualified for posting racy photographs of himself with scantily clad women (Johnson 2010). Although it is important for law enforcement agencies to use cyber-vetting procedures during the background investigation process for potential applicants, they must be diligent to keep in mind privacy concerns to ensure fair and just hiring practices (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010)

The use of social media for background investigations is so common that many potential recruits are aggressively warned to delete any social media accounts they have maintained sooner than later. The prevailing theory is that departments who fail to properly screen/monitor potential and current employees are open to negative media attention. Nearly one-third of 800 agencies responding to the IACP survey indicated their agency had experienced negative media attention from social media use by on-duty or off-duty employees (International Association of Chiefs of Police 2011, p. 11).

Global Social Media Impact

The use of social media is not limited to the United States. According to the International Telecommunication Union (2012), there are now over one billion users of social media worldwide. Police agencies in various countries have began to embrace the benefits of using social media. The Metropolitan Police of London, for example, have turned to Flickr in an effort to identify individuals involved in serious crimes. After the 2011 riots on London streets, local police posted a set of photos on Flickr showing people they believed to be involved in the riot. Police were asking the public to identify any individuals from the photographs captured from CCTV surveillance cameras in areas where stores were looted. On the Flickr page, police posted that their intent was to “bring to justice those who have committed violent and criminal acts” (Wortham 2011).

German police will soon use a social media platform to assist in criminal investigations. Police in the German state of Lower Saxony are preparing to use their networks of Facebook “friends” to find missing persons and find suspected criminals. The decision to use social media comes from their successful implementation of a pilot program in the capital of Lower Saxony. This pilot program helped solve six criminal investigations and two missing persons cases. Photographs of suspects were posted on Facebook asking for public assistance. Two cases were solved just hours after the information was uploaded to the site (Baghdjian 2012).

Police agencies across the globe are also using social media platforms for community outreach and citizen engagement. The Toronto Police Service (Canada) is highly regarded as one of the most forward-thinking law enforcement agency users of social media platforms, especially for community engagement. Service members can continually be seen tweeting and posting to Facebook and YouTube (Stevens 2011). Several police agencies in Australia have also begun to utilize the community outreach strategy. For example, the South Australian Police (SAPOL) has embraced multiple social media platforms in hopes of better connecting with communities at a local level. SAPOL launched Facebook and Twitter accounts as well as a YouTube Channel, in an effort to increase community support. SAPOL also shares information on such things as travel hazards and CCTV images of wanted offenders (Fedorowytsch 2012). In addition, the New South Wales Police Force’s eye-watch program brings community members and police together to communicate and solve problems using Facebook. The Facebook page includes crime prevention messages, alerts, updates, and other important community information. Since this social media platform has been implemented, there has been a 20 % increase in the information flow to the crime stoppers tip line (Maxwell 2012).

Police Facebook sites are also popular in New Zealand. One local police department’s Facebook page had more than 5,000 views within 3 months of implementation and is responsible for solving several burglaries. The police agency uses the Facebook page for leads, while the public uses it for information. A community constable in the police agency argues that it’s about bringing policing into the twenty-first century, using new tools available to get messages across to the community (Hueber 2012).

Opportunities And Challenges

There is little doubt that social media presents tremendous opportunities for the policing community. In a time of an unprecedented tightening of resources and ever-increasing demands on the policing community, organizations continue to struggle with the realities of doing more with less. In fact, the concept of “doing more with less” seems to be the prevailing mantra of most organizations today, and like other complex organizations, police are not immune from these demands. In a time of tough economic times that project to remain constant for the near future, police departments around the globe are strained with making the tough choices between what they can actually do in lieu of budgetary constraints. The opportunities are real and tangible.

In many ways, social media and related technologies offer to help law enforcement agencies grasp the realities those more contemporary philosophies of policing have to offer. Policing paradigms like community policing and problem-oriented policing have promised a new era in police community relations. These paradigms have stressed the centrality of the community to the policing function, the need to share information with the public, the value of connecting with the community on their terms, and a need to do these things within the natural constraints of available resources. While laudable, these goals are often hampered by a larger policing culture that does not necessarily support or recognize the value of community involvement in what can otherwise be considered “police business.”

Social media, however, offers the opportunity to facilitate these goals in important and unique ways, especially as it relates to information sharing. It affords the ability to fundamentally change the ground rules of police-community relationships in ways that increase transparency. “To truly develop a police culture that can exchange data, information, and intelligence” (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010, p. 5). Social media provides a relatively inexpensive fix for a broad array of information exchanges. It provides an opportunity for rich information exchange that is done on the terms of the public, but which is also not too taxing on either the police or the community. It offers the opportunity for meaningful information exchange and “dialogue.” It expands the “reach” of police departments into segments of the community they may otherwise have difficulty accessing. It is also remarkably efficient in doing so in a way that minimizes actual resource investment.

Yet social media offers more than just information sharing. It offers bi-directional communication that may actually increase public safety. The Los Angeles fires during the 2011–2012 New Year season are a noteworthy case in point. As described earlier in this research paper, this situation represented a rapidly expanding threat that pressed the limits of the public safety apparatus. The sheer magnitude of the unfolding events made it nearly impossible for serious investigations to be initiated during this early period. Police and fire officials quickly began to take notice that social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter were inundated with “chatter” about fires. Users were quickly “reporting” new fires, sometimes before 911 was even notified. Videos and pictures of freshly set blazes were appearing on these sites on a near instantaneous basis. Facebook and Twitter sites such as “Arson Watch L.A.” were used quickly and became venues for individuals interested in following the situation with the arsons to track the latest news, and have the most up-to-date information on what was occurring. By December 31st, public safety officials had begun to fully exploit this technology to both gather information about events, but also to communicate the most current information such as descriptions of suspects, particularly to segments of the community who might otherwise not frequent more conventional media outlets. Social media would eventually emerge as one of the primary ways Los Angeles police were able to communicate directly with the residents of affected neighborhoods. During similar situations in the past, police would have to organize last-minute community meetings in an effort to disseminate information to residents. As one police official noted, “By the time we’d be done with that, we’d be behind the curve, at best, 24 h.” Now, he argued, “we can turn out information in minutes” (Stevens and Winton 2012). By January 2nd, police had identified and apprehended a suspect after aggressively disseminating footage from a surveillance video depicting a person of interest leaving the scene of a crime. Social media played a vital role in helping police and fire officials manage a dynamic public safety threat.

The advantages of a favorable orientation toward social media are obvious, but less obvious are the potential complications presented by social media. Police organizations are inherently risk-adverse institutions intent on communicating to both internal and external constituencies a sense of professionalism. It is an occupation rife with potential complications associated with violations of standard operating procedures. The potential costs associated with scandal are a perennial management concern, and the first hint of scandal often brings a search for internal “suspects” on whom the blame can be laid. The action and inaction of police organizations can often be viewed through this “risk-averse” lens.

It should come as no surprise that many police departments around the country have been trepid about integrating social media into their broader community outreach initiatives. Numerous police departments, for example, have been faced with the very real challenges associated with the discovery of unsavory behavior on the part of sworn employees prominently displayed on social media sites. Examples of problematic behavior have included provocative pictures, apparent participation in illegal behavior, unsavory text-based comments, or other behavior that is considered unbecoming of an officer. One BBC News (2011) news story reported that 150 police officers in the UK were recently disciplined for inappropriate use of Facebook, at least 1 of which was fired. Infractions included harassing former paramours and the posting of racist comments. In one example, officers were disciplined after bragging of beating up members of the public during recent protests.

Concerns about the misuse of social media are evidenced by the extensive attention given to the “legal aspects” of social media use in IACP’s document titled Social Media, Concepts and Issues Paper (National Law Enforcement Policy Center 2010). This document, for example, devotes nearly two-thirds of the entire document to potential legal issues. Concerns raised include important issues such as first amendment rights of employees, the inappropriate dissemination of sensitive information via social media, and the impacts of personal use of social media on the employability of current and future employees. Agencies, IACP warn, have a duty to educate and inform their employees, both civilian and sworn, about departmental “proper use” policies.

Recommendations For Moving Forward

The very notion that nearly 10 % of the world’s population were active users of Facebook in just a few short years since the product was first developed signifies an unimaginable trajectory of growth. Social media is here to stay and its dominance as a mode of communication is growing by the day. It seems reasonable to assume that new and emerging forms of social media will be the dominant form of social interaction in the near future. With that in mind, police organizations are encouraged to exploit the advantages that social media has to offer, but to do so in a way that mitigates the potential negative tradeoffs. The following are a list of recommendations leaders should consider when planning for the adoption of social media:

- Clearly define your purposes: Agency leaders are encouraged to fully explore their rationale for the adoption of social media practices. Social media is not an all or nothing strategy. It is a set of technologies that evolve over time to fit the changing needs of the department. Different forms of social media have particular advantages/disadvantages and primary forms of social media should be driven by a clear understanding of its purpose. A chaotic approach that is neither focused nor strategic has the potential to not only be ineffective but actually be counterproductive if it communicates a sense of unprofessionalism. Agencies are encouraged to start small but smart.

- Commit: Regardless of the purposes social media plays in a police organization, commit to doing it well. Like static websites that rarely are updated with current content, the success of any social media strategy depends heavily on the extent to which agencies commit to making it part of operational strategies. The most successful social media strategies are those which help create a cultural of interaction and information sharing. Purposeful and consistent utilization of social media technology will help institutionalize its larger role in public safety.

- Appreciate the expectations social media creates on the part of the public: Police departments often justify their forays into social media based on the value of transparency and open communication. Such statements along with the accompanying technology may also create an expectation of transparency and open communication on the part of the public. Before an agency fully commits to the use of social media, agency leaders need to fully appreciate how such an effort may also create expectations for more information sharing. Organizational representatives need to create reasonable expectations about the circumstances of information sharing.

- Devotion of necessary resources: Agencies are encouraged to devote a reasonable set of resources to social media strategies in terms of both money and personnel. While social media is attractive to many agencies because it is seemingly inexpensive, this does not suggest there are no costs. Like any attempts at communication, social media strategies need to be viewed as an important component of community outreach and interaction.

Bibliography:

- Alexander D (2011) Using technology to take community policing to the next level. Police Chief 78:64–65

- Baghdjian A (2012) German police use Facebook pictures to nab crooks. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/02/07/us-germany-facebook-idUSTRE8161LG20120207. Accessed 12 Sept 2012

- Boyd DM, Ellison NB (2007) Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J Comput Mediat Commun 13(1):210–230

- Brady T (1997) The evolution of police technology (No NCJ 163601). U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, and Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Washington, DC

- BBC News (2011) 150 officers warned over Facebook posts. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-16363158. Accessed 18 Jan 2012

- Chou W-YS, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, Moser RP, Hesse BW (2009) Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res 11(4)

- Cisneros T (2009, April 1) Santa Ana launches online crime-reporting tool. http://www.ocregister.com/ news/reports-168503-police-online.html

- CNN (2012) Official: Los Angeles arson suspect under investigation in Germany. http://articles.cnn.com/2012-01-04/us/us_california-arson_1_los-angeles-arson-fireshollywood-apartment?_s¼PM:US

- Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C (2007) The benefits of facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput-Mediat Commun 12(4):1143–1168

- Facebook (2012) Timeline statistics. http://www. facebook.com/press/info.php?statistics. Accessed 12 Jan 2012

- Fedorowytsch T (2012) SA policing making Facebook connection. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-06-28/ police-facebook-pages-connect/4098074?section¼sa. Accessed 18 Sept 2012

- Forbes Magazine (2012) Forbes 400 richest Americans. http://www.forbes.com/profile/mark-zuckerberg/. Accessed 15 July 2012

- Gazaway C (2011) KSP turning to social media for recruits. http://www.wave3.com/story/15176887/kspturning-to-social-media-for-recruits. Accessed 29 Jan 2012

- Greenhow C, Robelia B (2009) Old communication, new literacies: social network sites as social learning resources. J Comput-Mediat Commun 14(4):1130–1161

- Howard PN, Hussain MM (2011) The role of digital media. J Democr 22(3):35–48

- Hueber A (2012) Fighting crime with Facebook. http://www.theaucklander.co.nz/news/fighting-crimefacebook/1289252/. Accessed 1 Sept 2012

- International Association of Chiefs of Police (2011) 2011 IACP Social media survey. International Association of Chiefs of Police, Alexandria International Association of Chiefs of Police (n.d.-a) Case Study: Colorado Springs, Colorado, Police Department – community education, community engagement. http://www.iacpsocialmedia.org/ Resources/CaseStudy.aspx?termid¼9&cmsid¼4734. Accessed 1 Sept 2012

- International Association of Chiefs of Police (n.d.-b) Houston, Texas, Police Department – Blogging for recruitment and beyond. http://www.iacpsocialmedia. org/Resources/CaseStudy.aspx?termid¼9&cmsid¼4734. Accessed 12 Jan 2012

- Johnson K (2010) Police recruits screen for digit dirt on Facebook, etc. http://www.usatoday.com/tech/news/2010-11-12-1Afacebookcops12_ST_N.htm. Accessed 3 Jan 2012

- Kaplan AM, Haenlein M (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horiz 53(1):59–68

- LeVeque T (2011) Introducing social media to an emergency operations center. http://lawscommunications. com/category/tom-le-veque. Accessed 21 Nov 2011

- Manning PK (1996) Information technology in the police context: the “sailor” phone. Inform Syst Res 7(1):52–62

- Maxwell JJ (2012) A new platform for community engagement and neighbourhood watch in the 21st century. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-06-28/ police-facebook-pages-connect/4098074?section¼sa. Accessed 1 Sept 2012

- Mazerolle L, Rogan D, Frank J, Famega C, Eck JE (2003) Managing citizen calls to the police: an assessment of non-emergency call systems. United States Department of Justice, Washington, DC

- Michalos S (2010) Social media to solve crimes. Journal Gazette. http://www.journalgazette.net/article/20100620/NEWS07/306209898/0/FRONTPAGE

- National Law Enforcement Policy Center (2010) Social media: concepts and issues paper. International Association of Chiefs of Police, Alexandria

- Paquet S (2002) Personal knowledge publishing and its uses in research. Seb’s Open Res Oct:1–15

- Pew Research Center (2011) Global digital communication: texting, social networking popular worldwide. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

- Rose A, Timm H, Pogson C, Gonzalez J, Appel E, Kolb N (2010) Developing a cybervetting strategy for law enforcement. International Association of Chiefs of Police, Alexandria

- Smith A (2011) Why Americans use social media. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

- Stevens L (2011) Social media quick tip: 3 reasons why LEOs should be on linkedin.http://www.lawofficer. com/article/technology-and-communications/socialmedia-quick-tip-3-reaso

- Stevens L (2011) The Toronto Police Service launches social media program. http://connectedcops.net/2011/07/25/the-toronto-police-service-launches-social-mediaprogram/. Accessed 12 Sept 2012

- Stevens M, Winton R (2012) Social media sites are crucial in arson probe. Los Angeles Times. http://articles. latimes.com/2012/jan/02/local/la-me-social-mediaarson-20120103

- Varano SP, Cancino JM, Glass J, Enriquez R (2007) Police information systems. In: Schafer JA (ed) Policing 2020. Federal Bureau of Investigations, Washington, DC

- Wagley J (2011) Police embrace social media. Secur Manage 55(11):36–37

- Wilson JM, Castaneda LW (2011) Most wanted: law enforcement agencies pursue elusive, qualified recruits. RAND Rev 35(1):25–29

- Wortham J (2011) London police use Flickr to identify looters. http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/09/ london-police-use-flickr-to-identify-looters/. Accessed 12 Sept 2012

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.