This sample Victim-Focused Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Reppucci and Haugaard (1989) have argued that before designing prevention programs to prevent sexual victimizations, we should first know what actually happens in sexual offenses. In other words, prevention should be based on empirical studies focusing on a detailed analysis of the actual offense not anecdotal accounts. To our knowledge, a very limited number of studies have been completed on victim resistance and its impact on the offender-victim interchange and related outcomes in child sexual abuse. A clearer understanding of the patterns in offender-victim interchanges may assist in informing and improving prevention programs. This research paper begins with an overview of child sexual abuse, leading to current knowledge regarding offender-victim interchange and victim resistance. Second, it reviews victim-focused prevention programs and its effectiveness in reducing the number of sexual abuse incidents. Lastly, it makes a number of recommendations as to potential future directions.

Fundamentals

Child Sexual Abuse: An Overview

In child sexual abuse (CSA), the victim is most often in a trusting relationship with the offender with whom they share an emotional attachment. Approximately 95 % of CSA are committed by offenders already known to the victim, with 47 % who were related to or lived with the victim (Smallbone and Wortley 2000). Most incidents of sexual abuse occur in a familial or acquaintance relationship where the offender has established a previous nonsexual relationship with the child, often in authority and care-taking roles (Smallbone and Wortley 2000). The “grooming process” in CSA can be subtle, involving a graduation of giving attention, touching, and sexual talk to more explicit sexual behaviors, but is rarely associated with overt force and violence (e.g., Leclerc et al. 2011a; Smallbone and Wortley 2000). Offenders often target children who appear to have low confidence and self-esteem, who are more vulnerable to emotional exploitation (Elliott et al. 1995). CSA is a highly underreported form of crime, where studies have found as little as 3 % of incidents were reported to the police (Finkelhor and Dziuba-Leatherman 1994). Explanations such as reluctance to see the offender face serious police investigations, fear of stigmatization and retribution, and fear of blame or disbelief from non-offending adults have been speculated (Finkelhor and Ormrod 2001).

The Victim In Focus: Offender-Victim Interchange

Differences have been found in CSA regarding female and male children. Offender sexual behaviors such as touching and fondling are predominant for girls, whereas masturbatory, oral, and anal abuse is more likely for boys (Ketring and Feinaur 1999). Girls are more likely to be abused by familial offenders (in particular, by a stepfather), whereas boys are more likely to be abused by nonfamilial offenders (by a family friend) and also experience threats and force in conjunction with the abuse (Gold et al. 1998). These differences are indicative that offender methods and crime-commission processes vary for boys and girls. Due to the complex nature of offender-victim relationships, the offender-victim interaction is of particular importance in understanding the processes and outcomes in CSA.

Although recent reconceptualization of CSA from a criminological standpoint saw progress toward victim incorporation in crime analyses, only a few studies have examined offender-victim interaction in CSA with a deeper focus. An example is taking into account victim characteristics (e.g., Leclerc et al. 2009) and including the temporal order of events (e.g., Leclerc et al. 2011a). To date, research has suggested that the degree of intrusiveness of offenders’ sexual behaviors in CSA is contingent on the victim performing sexual behaviors on the offender, which is in turn dependent on the offender’s modus operandi (MO) or strategies used to gain the victim’s cooperation (Leclerc and Tremblay 2007). Furthermore, in examining what factors might lead to a more intrusive sexual outcome, Leclerc et al. (2009) found that modus operandi as well as victim characteristics of gender and age had an important effect on crime event outcomes. Their findings suggest that offenders who get their victim to perform sexual behaviors on them (or victim participation) need to first secure the victim’s trust through manipulation (including seduction, money and gifts, playing with the victim, and intoxicating the victim with alcohol or drugs). In fact offenders who used manipulation strategies were nearly six times more likely to make their victim perform sexual behaviors on them in sexual episodes; however, they were also less likely to perform penetration for female victims. In their study, Leclerc et al. (2009) suggested that offenders who used manipulation were more likely to perceive their victims as partners and therefore stopped short of performing penetration when met with resistance. Manipulation was found to decrease the risk of penetration for female victims, but not male victims, and it was assumed that female victims are more reluctant to experience intrusive sexual behaviors than male victims. This interpretation was supported by another pattern found in the study – an interaction effect was discovered between victim characteristics and sexual outcomes. Offenders were more likely to make the victim perform sexual behaviors on them in sexual activity as the victim became older when abusing a male victim. The opposite effect was apparent for female victims; older female victims were less likely to perform sexual behaviors in sexual episodes but were at greater risk of experiencing penetration.

A broader way to examine CSA is by mapping the complete sequence and events of the crime, such as through the use of crime scripts. Crime scripts evolved as an extension of the event model in rational choice perspective, where Cornish extended the analysis of offender decision-making from target selection to the whole process of the crime. A crime script (Cornish 1994) is a step-by-step account of the procedures and decisions used by offenders during crime commission. It breaks the crime down into steps or scenes, which enables potential for situational prevention at each step of the crime, and acts as a framework for breaking down the crime-commission process. The first empirical CSA crime script was developed by Leclerc et al. (2011a), which drew on the script model provided by Cornish (1994). It outlined the sequence of behaviors in CSA through a comprehensive framework. This script involved several stages including (1) entry to setting, setting where victim is first encountered; (2) instrumental initiation, gaining trust strategies; (3) continuation, proceeding to crime location strategies; (4) location selection, location for sexual contact; (5) instrumental actualization, isolation; (6) completion, gaining cooperation strategies; (7) outcomes, amount of time spent in sexual activity, victim participation, and offender sexual behaviors; and (8) postcondition, avoiding disclosure strategies. By breaking down the sequence of actions into a script, it allowed the authors to devise potential situational intervention strategies at different stages of the script, such as parent training sessions on modus operandi and context of abuse and information sessions for teachers on how to detect intrafamilial abuse and limit long-term and repetitive access to children. Offender-victim interaction was incorporated in the script by examining crime event outcomes; however, in this study victim resistance was not accounted for.

Victim Resistance

Victim resistance has been examined in a range of crimes. It has been argued that the interaction between victims and offenders largely determines the severity and level of injury during the crime (Block 1981). Studies that incorporated violence-resistance sequence analysis found that related injuries were attributed to the offender’s physical attack rather than the subsequent result of victim resistance (Ullman and Knight 1991, 1992). This indicates that apparent inconsistencies in research may be explained by factoring in sequential relations of offender attack, victim resistance strategies, and assault outcomes. Although it is unclear whether victim resistance decreases the likelihood of injury, results generally indicate that victim resistance is successful and at worst inconsequential for different types of crime including robbery, burglary, sexual offenses against women, assault, and personal larceny (Tark and Kleck 2004).

However, there exists a discrepancy in CSA. The issue of victim resistance is more complicated in CSA, as victims represent a vulnerable group with less ability to physically resist against an adult offender. Finkelhor et al. (1995a, b) examined the efficacy of child’s resistance and determined that children who resisted were more likely to suffer injuries and did not experience lower levels of victimization. A few earlier studies in victim resistance asked the offenders regarding what self-protection strategies children should use to avoid abuse (e.g., Elliott et al. 1995). Suggestions made included saying “no” to offenders, telling someone about the abuse, trying to get away, and learning about the proper touching of private parts. In more recent research, the efficacy of resistance strategies in CSA was analyzed based on empirical evidence in crime events. Of the different forms of resistance, it was discovered that the most successful resistance strategies included saying “no” and being assertive and the less effective resistance strategies included trying to get away, fighting back, and yelling for help (Leclerc et al. 2011b). In Leclerc et al.’s (2011b) sample of 94 adult offenders, a total of 74.3 % of offenders reported that their victim was able to avoid sexual contact at some point by telling them they do not want to participate in such activities, and 56.4 % by saying “no.” Fighting back (11.8 %) and yelling for help (4 %) were the least successful strategies to avoid sexual contact.

Leclerc, Wortley, and Smallbone’s (2010) work supported this finding and added another dimension into their analysis by examining the circumstances where children were more likely to successfully resist abuse. Factors such as preoffense situation, offender modus operandi, and victim characteristics were examined in association with victim resistance in CSA. In relation to victim characteristics, it was found that younger girls were more likely to employ non-forceful verbal resistance than older girls and also use a greater number of strategies. Additionally, the older the child, the less likely they were to use non-forceful verbal resistance. As younger girls were more likely to use self-protection strategies, they were able to prevent episodes of abuse than older girls. This is in line with Asdigian and Finkelhor’s (1995) study, which found that younger victims were more likely to use passive forms of resistance and a greater number of resistance strategies; however, older children were more likely to use active forms of resistance during the assault. Leclerc et al. (2010) found that victim resistance was also affected by offender modus operandi. Examination of offender modus operandi and victim resistance at a multivariate level showed that only violence was significantly linked to victim resistance. Offender violence was related to all forms of resistance, where the use of violence increased the chance of victim resistance by nearly five times when compared to strategies without violence (e.g., desensitization, gifts/privileges). Assuming that violence preceded resistance, it was interpreted that victims had no other way to avoid abuse but to resist in this context.

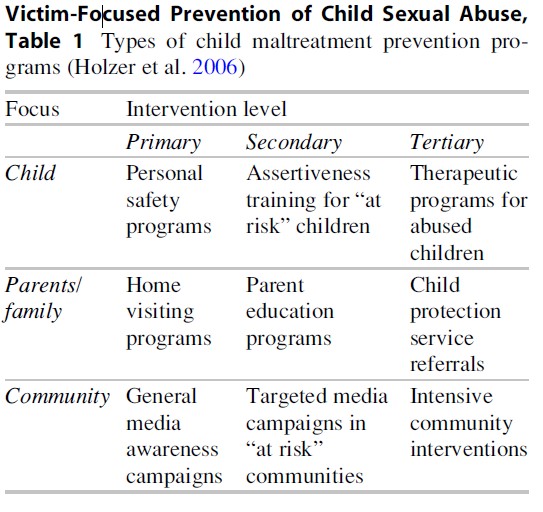

Victim-Focused Prevention Programs

Crime prevention of CSA can take many forms, including situational crime prevention, developmental crime prevention, community approaches, and criminal justice interventions. Current approaches to CSA prevention are dominated by formal interventions that take effect only after the crime has been committed, such as investigations, selective incapacitation, and offender rehabilitation (Smallbone et al. 2008). Against this backdrop, child protection programs have emerged as a non-criminal-justice response and alternative prevention to CSA incidents. Victim-focused prevention largely revolves around personal safety programs that seek to equip children with self-protective skills, including recognizing and avoiding sexually abusive situations. CSA prevention programs operate on several levels. The overall aim is to prevent potential occurrences and reoccurrences of child maltreatment, as well as reduce the likelihood of intergenerational transmission, where victims of CSA become perpetrators of the next generation. A composite approach to prevention programs was developed from the public health model of disease prevention, based on the level of severity: child maltreatment programs are commonly categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary interventions (Tomison and Poole 2000). An example table of program classifications is adapted from Holzer, Bromfield, Richardson, and Higgins (2006), as seen in Table 1.

Primary interventions are strategies aimed toward targeting communities and building public resources. This includes personal safety programs taught in schools for children and parent education such as home visiting programs designed to increase knowledge of child development, assist in parenting skills, and normalize the challenges and difficulties faced in parenting. Secondary interventions target families with higher risk of child abuse, involving interventions such as home visitation, parent education, and skills training. This involves early screening to detect children who are potentially at risk due to the presence of one or more risk factors for child maltreatment, in order to prioritize early intervention. Tertiary interventions involve families in which child abuse has already occurred and is therefore seen as a reactive approach. Interventions such as statutory child protection and child welfare services seek to prevent the reoccurrence of abuse and mitigate the negative impacts of trauma and maltreatment. In summary, prevention programs differ in their focus, whether it is pre-intervention or post-intervention, or vary in their target audience. Education can be specified for parents, for children, for the family as a unit, for the community, or for the offender/ potential offenders. Greater emphasis has been placed on primary and secondary interventions following reports indicating greater difficulties in treating abusive parents at the tertiary level, as such abuse may have become a fixed pattern in parent-child interactions (Geeraert et al. 2004). Recognition of the importance of proactive strategies has increased among government bodies, community alliances, and nongovernment organizations. Victim-focused safety programs adopted across schools are included in this category.

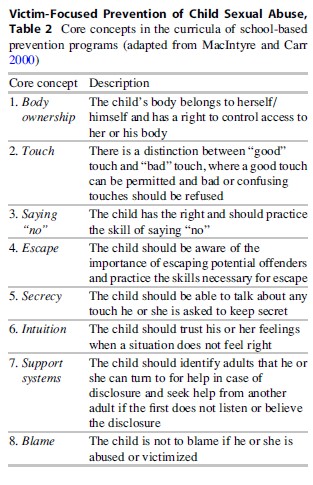

MacIntyre and Carr (2000) summarized the core concepts generally taught in school-based prevention programs, including body ownership, touch, saying “no,” escape, secrecy, intuition, support systems, and blame (see Table 2). Body ownership and saying “no” try to teach the child that they have a right to refuse other people access to his or her body. This also teaches children to be assertive and that the child’s body belongs to himself/herself. Touch and intuition methods rely on the child’s ability to detect what feels confusing or wrong, including the concepts of “good touch, bad touch.” Escape includes teaching methods and skills to escape potential offenders. Secrecy and support systems encourage disclosure from the child by assuring children they can talk about anything (even what they were told to keep a secret) and identify a trusted network of adults to whom they can do so. Programs also try to reduce victim blame by assuring children that they are not responsible and are not to blame if he or she is abused.

Are Self-Protection Programs Effective In Reducing Child Sexual Abuse Incidents?

Since its early development, programs such as the Protective Behaviors (PB) program from the 1970s have been subject to several criticisms. For example, early programs were criticized for not incorporating children’s developmental and learning needs in the concepts of the program (Finkelhor and Strapko 1992). Also, it was pointed out that the child’s ability to clearly recognize and safely respond to unsafe feelings was ineffective, as adults are generally viewed as protectors (Briggs 1991). This is particularly relevant in CSA where 95 % of incidents are perpetrated by adults with prior established relationships with the victim (Smallbone and Wortley 2000). For young children, the attachment toward the offender combined with lack of sexual knowledge means the abuse might not be recognized by the child. This limits the effectiveness of understanding what constitutes as a “bad touch” and increases the risk of victim shame and self-blame.

Outcomes of child safety programs are generally determined by evaluations during a follow-up period. There are three main types of evaluations (Richardson and Tomison 2004): process evaluations examine how a program has been implemented or practiced; impact evaluations investigate whether a program has achieved its operational goals, such as increased knowledge, skill gain, or increased disclosure. Finally, outcome evaluations determine whether the program has resulted in reductions of subsequent incidence of CSA. The latter has rarely been examined by studies, and to date only one study by Gibson and Leitenberg (2000) reported positive results: a survey of 825 female undergraduates revealed that 8 % of students experienced subsequent child sexual victimization after attending protection programs, compared to 14 % of students who had not participated in a program. This result is a contrast to Finkelhor et al.’s (1995a, b) study, which examined the efficacy of self-protection in several types of victimization, including assaults by peers, family members, gangs, kidnappings, and sexual offenses. First, Finkelhor et al. (1995a) completed telephone interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,000 children who participated in school-based prevention programs. Children who took part in prevention programs were more likely to use self-protection strategies, to disclose abuse when it does occur, and to perceive themselves as having been more effective in avoiding or minimizing the harm of sexual victimization and were less prone to self-blame. It was also found, however, that children involved even in the most comprehensive personal safety programs were more likely to suffer injuries in coping with sexual assaults. According to the authors, this finding was perhaps related to children’s more aggressive resistance. In a follow-up study, Finkelhor et al. (1995b) then recontacted previous participants for a second interview, with the average delay being 15 months. Children involved even in the most comprehensive personal safety programs did not experience lower levels of completed victimizations.

However, in actual CSA situations using recent offender self-report data, some strategies were found to be successful in avoiding sexual abuse, such as saying “no” (Leclerc et al. 2010). Although the sample used in the study was limited to children who were ultimately abused at some point, the research indicates that some forms of resistance may be effective in avoiding episodes of sexual contact in real-life situations. In summary, while there is general evidence supporting process and impact evaluations of child safety programs (MacIntyre and Carr 2000), evidence regarding outcome evaluations is lacking and inconsistent. Whether programs are successful in reducing the incidence of subsequent sexual victimization is still unclear (Smallbone et al. 2008).

Where To From Here?

A better understanding of offender-victim interchanges has the potential to contribute to child sexual abuse prevention and inform prevention programs. Below is a list of general recommendations to guide future studies.

Sequence Of Behaviors (Offender-Victim/ Offender-Outcome)

Although it has been demonstrated that offender- victim interchanges can impact the outcome, the time sequence of behaviors has not been incorporated. For example, offender response to victim reaction and associated outcomes has yet to be studied. This sequence of behaviors can be valuable in understanding why some resistance strategies are more effective than others. An excellent example of this kind of study is Luckenbill’s (1977) work in criminal homicide. In the examination of 70 cases, he found that victims did not play a passive role in the event. Murder was found to be the outcome of a dynamic interchange between the offender, victim, and bystanders. The actions of the actors were shaped in part by each other. Alternatively in sexual offending, when incorporating sequence analysis to sexual offenses against women, it was found that victim injury generally did not precede offender attack (Ullman and Knight 1991, 1992). Therefore, victim resistance is often adopted in response to offender violence. By factoring in sequential relations of offender attack, victim resistance, and assault outcomes, it was further discovered that resistance rarely precedes injury, where 85 % of women studied responded with physical force only in reaction to the offender’s initiated violence (Ullman and Knight 1992), and that most forms of resistance are not significantly associated with higher rates of subsequent victim injury (Kleck and Sayles 1990). Similarly, by incorporating sequence analysis to CSA, it will provide a better framework to understand the offense process and interpret the associated outcomes.

Scripts Based On Victims

Although Leclerc et al. (2011a) developed an empirical script model in CSA, the sequence of events can be examined in greater detail using scripts or script tracks. For situational purposes, it is important to be crime-specific. Other offense characteristics such as victim characteristics, victim resistance, encounter settings, or offense location could be incorporated. Studies have already shown the victim gender and age have an impact on the crime (e.g., Leclerc et al. 2009, 2010). For example, what is the crime script for sexual offenses against younger boys compared to older boys? What is the crime script for sexual offenses in public places compared to private locations? Are there differences in offender modus operandi or victim reaction? By operating at a higher level of specificity, crime scripts may offer further insight into prevention strategies. This is valuable for prevention programs. If programs can be tailored to the victim’s unique needs and circumstances, based on higher likelihood of the situations they may encounter, more effective and informed advice can be given. This is congruent with Asdigian and Finkelhor’s (1995) recommendation, which does not encourage a one-size-fits-all approach to CSA prevention.

What Works, What Does Not, And What Is Promising?

Further impacts and links regarding offense characteristics and victim resistance can be investigated in greater detail and with larger sample sizes. Other factors such as duration of the abuse, escalation pattern, victim gender, guardianship, offender-victim relationship, and settings can be explored. In particular, analyzing the crime process for girls and boys has potential to inform self-protection programs. Examining the efficacy of victim resistance in child sexual abuse empirically is also important. Although some studies have found evidence that some self-protection strategies may be more effective than others [i.e., saying “no” and saying they do not want to participate (Leclerc et al. 2011b)], whether these strategies work for boys and girls of different ages and whether the effectiveness varies in different contexts can be explored. This evidence gives practitioners clearer indications of what works and what does not and what has the potential to be developed. An example to draw from may be in the area of sexual offenses against women, as victim resistance in this area has been more thoroughly explored in comparison. For instance, several types of victim response have been central to women’s rape avoidance studies, including forceful physical resistance, nonforceful physical resistance, forceful verbal resistance, and non-forceful verbal resistance. Forceful physical resistance has been consistently related to successful rape avoidance and found to be directly related to less severe sexual abuse without increase of physical injury (Ullman and Knight 1991). The method of resistance also affected the outcome, where forceful fighting and screaming was related to decreased severity of sexual abuse. Non-forceful verbal resistance such as pleading, begging, and reasoning, however, were related to greater severity of sexual abuse (Ullman and Knight 1991). Better understanding of victim resistance strategies in CSA, its efficacy and associated outcomes, and the contexts in which it occurs has important implications for prevention programs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite existing knowledge in the field, there are still many avenues to be investigated in CSA. Currently the effectiveness of child protection programs in reducing subsequent victimization has not yet been validated. The design of early victim-focused prevention programs was subject to various criticisms. Some concepts adopted in programs, such as “bad touch” or “unsafe feelings,” are ineffective for children (Briggs 1991) and based on common assumptions rather than empirical research. This is in part due to a lack of understanding of the processes that occurs in child sex offenses. Existing literature in CSA indicates that victim characteristics (such as gender and age) and offender modus operandi are important elements that can influence abuse outcomes in terms of severity and level of injury (Leclerc et al. 2009). These factors also impact victim resistance (Leclerc et al. 2010). However, there is still much to be explored and understood regarding the child sexual abuse crime event. The complexity of CSA means that without a more detailed context it can be hard to determine the complete behavioral sequences and interactions in the crime. This is an important area to investigate, as the understanding of what happens during an offense is essential in driving the design of prevention programs (Reppucci and Haugaard 1989; Smallbone et al. 2008). Building further knowledge of patterns in offender-victim interchange may help to interpret crime event outcomes and identify intervention strategies for prevention programs. The recommendations mentioned above provide a guideline for future research to inform practitioners; the pursuit of such knowledge can improve practical intervention and programs aimed at reducing the risk of child sexual abuse.

Bibliography:

- Asdigian N, Finkelhor D (1995) What works for children in resisting assaults? J Interpers Violence 10:402–418

- Block R (1981) Victim-offender dynamics in violent crime. J Crim Law Criminol 72:743–761

- Briggs F (1991) Child protection programs: can they protect young children? Early Child Dev Care 67:61–72

- Cornish DB (1994) The procedural analysis of offending and its relevance for situational prevention. In: Clarke RV (ed) Crime prevention studies, vol 3. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey

- Elliot M, Browne K, Kilcoyne J (1995) Child sexual abuse prevention: what offenders tell us. Child Abuse Negl 19:579–594

- Finkelhor D, Dziuba-Leatherman J (1994) Children as victims of violence: a national survey. Pediatrics 94:413–420

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK (2001) Factors in the underreporting of crimes against juveniles. Child Maltreat 6:219–229

- Finkelhor D, Strapko N (1992) Sexual abuse prevention education: a review of evaluation studies. In: Willis DJ, Hoder EW, Rosenberg M (eds) Child abuse prevention. Wiley, New York

- Finkelhor D, Asdigian NL, Dziuba-Leatherman J (1995a) The effectiveness of victimization prevention instruction: an evaluation of children’s responses to actual threats and assaults. Child Abuse Negl 19:141–153

- Finkelhor D, Asdigian NL, Dziuba-Leatherman J (1995b) The effectiveness of victimization prevention programs for children: a follow-up. Am J Public Health 85:1684–1689

- Geeraert L, Noortgate WVD, Grietens H, Onghena P (2004) The effects of early prevention programs for families with young children at risk for physical child abuse and neglect: a meta-analysis. Child Maltreat 9:277–291

- Gibson LE, Leitenberg H (2000) Child sexual abuse prevention programs: do they decrease the occurrence of child sexual abuse? Child Abuse Negl 24:1115–1125

- Gold SN, Elhai JD, Lucenko BA, Swingle JM, Hughes DM (1998) Abuse characteristics among childhood sexual abuse survivors in therapy: a gender comparison. Child Abuse Negl 22:1005–1012

- Holzer PJ, Bromfield LM, Richardson N, Higgins DJ (2006) Child abuse prevention: what works? The effectiveness of parent education programs for preventing child maltreatment. Research brief no. 1, from http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/researchbrief/ rbl.html

- Ketring SA, Feinaur LL (1999) Perpetrator-victim relationship: long-term effects of sexual abuse for men and women. Am J Fam Ther 27:109–120

- Kleck G, Sayles S (1990) Rape and resistance. Soc Probl 37:149–162

- Leclerc B, Tremblay P (2007) Strategic behavior in adolescent sexual offenses against children: linking modus operandi to sexual behaviors. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 19:23–41

- Leclerc B, Proulx J, Lussier P, Allaire J-F (2009) Offender-victim interaction and crime event outcomes: modus operandi and victim effects on the risk of intrusive sexual offenses against children. Criminology 47:595–618

- Leclerc B, Wortley R, Smallbone S (2010) An exploratory study of victim resistance in child sexual abuse: offender modus operandi and victim characteristics. Sex Abuse J Res Treat 22:25–41

- Leclerc B, Wortley R, Smallbone S (2011a) Getting into the script of child sex offenders and mapping out situational prevention measures. J Res Crime Delinq 48:209–237

- Leclerc B, Wortley R, Smallbone S (2011b) Victim resistance in child sexual abuse: a look into the efficacy of self-protection strategies based on the offender’s experience. J Interpers Violence 26:1868–1883

- Luckenbill DF (1977) Criminal homicide as a situated transaction. Soc Probl 25:176–186

- MacIntyre D, Carr A (2000) Prevention of child sexual abuse: implications of programme evaluation research. Child Abuse Rev 9:183–199

- Reppucci ND, Haugaard JJ (1989) Prevention of child sexual abuse: myth or reality. Am Psychol 44:1266–1275

- Richardson N, Tomison AM (2004) Evaluating child abuse prevention programs. Child Abuse Prevention Resource Sheet 5, from http://wwww.aifs.gov.au/nch/sheets/rs5.html

- Smallbone S, Wortley R (2000) Child sexual abuse in Queensland: offender characteristics and modus operandi (full report). Queensland Crime Commission, Brisbane

- Smallbone SW, Marshall W, Wortley R (2008) Preventing child sexual abuse: evidence, policy and practice. Willan, Cullompton

- Tark J, Kleck G (2004) Resisting crime: the effects of victim action on the outcomes of crimes. Criminology 42:861–909

- Tomison AM, Poole L (2000) Preventing child sexual abuse and neglect. Findings from an Australian audit of prevention programs. http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/ pubs/auditreport.html

- Ullman SE, Knight RA (1991) A multivariate model for predicting rape and physical injury outcomes during sexual assaults. J Consult Clin Psychol 59:724–731

- Ullman SE, Knight RA (1992) Fighting back: women’s resistance to rape. J Interpers Violence 7:31–43

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.