This sample Economics and Corporate Social Responsibility Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the economics research paper topics.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) constitutes an economic phenomenon of significant importance. Today, firms largely determine welfare through producing goods and services for consumers, interest for investors, income for employees, and social and environmental externalities or public goods affecting broader subsets of society. Stakeholders often take account of ethical, social, and environmental firm performance, thereby changing the nature of strategic interaction between profit-maximizing firms, on one hand, and utility-maximizing individuals, on the other hand.

Hence, CSR is referred to as “one of the social pressures firms have absorbed” (John Ruggy, qtd. in The Economist, January 17, 2008, special report on CSR) and considered to “have become a mainstream activity of firms” (The Economist, January 17, 2008; Economist Intelligence Unit, 2005). Many (inter)national firms strive to achieve voluntary social and environmental standards (e.g., IS014001), and the number of related certifications in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries as well as in emerging market economies is constantly growing. Broad access to the Internet as well as comprehensive media coverage allow the public to monitor corporate involvement with social ills, environmental degradation, or financial contagion independent of geographical distance. A 2005 U.S. survey by Fleishman-Hillard and the National Consumers League (Rethinking Corporate Social Responsibility) concludes that technology is changing the landscape in which consumers gather and communicate information about CSR and that Internet access has created a “more informed, more empowered consumer … searching for an unfiltered view of news and information.”

In light of (a) such “empowered” market participants able to discipline firms according to their preferences and (b) the public good nature of business “by-products,” policy makers must reevaluate the border between public and corporate social responsibility. In this context, Scherer and Palazzo (2008) note that “paradoxically, today, business firms are not just considered the bad guys, causing environmental disasters, financial scandals, and social ills. They are at the same time considered the solution of global regulation and public goods problems” (p. 414). In sum, CSR opens up a wide array of economic questions and puzzles regarding firm incentives behind voluntary and costly provision of public goods as well as the potential welfare trade-off between their market and government provision. While economic research had initially addressed the question of whether CSR possesses any economic justification at all, it has recently shifted to how it affects the economy, stressing the need of analytical machinery to better understand the mechanisms underlying CSR as well as its interaction with classical public policy. Therefore, the objective of this research paper is to identify, structure, and discuss essential economic aspects of CSR.

At first sight, CSR appears to be at odds with the neoclassical assumption of profit maximization underlying strategic firm behavior. Corporate social performance often means provision of public goods or reduction of negative externalities (social or environmental) related to business conduct. As public goods and externalities entail market failure in the form of free riding or collective action problems, government provision through direct production or regulation may be most efficient, a concept generally known as Friedman’s classical dichotomy. If firms still decide to engage in costly social behavior beyond regulatory levels (i.e., CSR), then why would they voluntarily incur these costs, and is this behavior overall economically efficient?

The attempt to answer these questions leads to the firm’s objective—maximizing shareholder value—and its dependence on the nature of shareholders’ and stakeholders’ preferences. Shareholders and investors can be profit oriented and/or have social and environmental preferences. The same is true for consumers, while workers may be extrinsically and/or intrinsically motivated. This heterogeneity in preferences (i.e., the presence of nonpecuniary preferences alongside classical monetary ones) is able to shed light on CSR within standard economic theory.

Another important issue intrinsically related to CSR concerns information asymmetries between firms and stakeholders. Reputation and information are important determinants of consumer, investor, employee, or activist behavior and, therefore, firm profits. Hence, many firms proactively report on their CSR activities and consult governments, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and private auditors to earn credibility. In short, firms seek to build and maintain social or environmental reputation in markets characterized by information asymmetry and socially or environmentally conscious agents.

While information economics, contract, and organization theory provide a suitable framework to analyze the motivations and strategies beneath CSR, public economics and industrial organization may enhance the understanding of how the underlying “social pressures” might affect market structure, competition, and total welfare. The remainder of this research paper is organized as follows: The second section defines CSR and discusses the classical dichotomy between the public and private sectors in light of CSR. The third section outlines the crucial role of preferences in explaining and conceptualizing CSR. The fourth section gives a structured overview of distinctive theoretic explanations of strategic CSR in light of some empirical evidence. The fifth section concludes.

What Is CSR? From Definition to Analysis

Before entering economic analysis, the stage has to be set by defining corporate social responsibility. In practice, a variety of definitions of CSR exists. The European Commission (2009) defines corporate social responsibility as “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis.” The World Bank (n.d.) states,

CSR is the commitment of businesses to behave ethically and to contribute to sustainable economic development by working with all relevant stakeholders to improve their lives in ways that are good for business, the sustainable development agenda, and society at large.

A notion similar to “voluntary behavior” can be found in definitions that refer to either “beyond compliance,” such as those used by Vogel (2005) or McWilliams and Siegel (2001), who characterize CSR as “the fulfillment of responsibilities beyond those dictated by markets or laws,” or to “self-regulation,” as suggested by Calveras, Ganuza, and Llobet (2007), among others.

These attempts to define CSR reveal two basic conceptual features: First, CSR manifests itself in some observable and measurable behavior or output. The literature frequently refers to this dimension as corporate social or environmental performance (CSP or CEP). Second, the social or environmental performance or output of firms exceeds obligatory, legally enforced thresholds. In essence, CSR is corporate social or environmental behavior beyond levels required by law or regulation. This definition is independent of any conjecture about the motivations underlying CSR and constitutes a strong fundament for economic theory to investigate incentives and mechanisms beneath CSR. Note that, while Baron (2001) takes the normative view that “both motivation and performance are required for actions to receive ‘the CSR label,'” it is proposed here that linking a particular motivation to the respective performance is required for the action to receive “the correct CSR label” (e.g., strategic or altruistic). From an economic point of view, the “interesting and most relevant” form of CSR is strategic (i.e., CSR as a result of classical market forces), while McWilliams and Siegel’s (2001) definition would reduce CSR only to altruistic behavior.

The logical next step is to build the bridge from definition to economic analysis. CSR often realizes as a public good or the reduction of a public bad. Hence, revisiting the classical dichotomy between state and market appears to be important. Relevant works that relate CSR with public good provision include Bagnoli and Watts (2003) and Besley and Ghatak (2007), who explicitly define CSR as the corporate provision of public goods or curtailment of public bads. Firms may produce a public good or an externality jointly with private goods, either in connection with the production process of private goods (e.g., less polluting technology such as in Kotchen [2006], or safe/healthy working conditions) or linked to the private good/service itself (e.g., less polluting cars or energy-saving light bulbs). This perspective on CSR relates directly to earlier work by J. M. Buchanan (1999), who referred to such joint provision of a public and private good as an “impure public good,” and relevant insights such as those derived by Bergstrom, Blume, and Varian (1986) in their seminal paper on the private provision of public goods, which can be readily translated into the CSR framework. For example, Bergstrom et al. focused on the interaction between public and private (individual) provision of the public good and the effect on overall levels of provision and concluded that public provision crowds out its private counterpart almost perfectly. Along these lines, Kotchen (2006) compares joint corporate provision of private and public goods in “green markets” (where the private good is produced with an environmentally friendly production technology) and separate provision of either, leading to the similar conclusion that the very same crowding out takes place between corporate provision and individual provision and may even lead to an overall reduction in the level of the public good. More precisely, Besley and Ghatak (2001) notice that public goods provision has dramatically shifted from public to mixed or complete private ownership in recent years, while Rose-Ackerman (1996) phrases the problem as the “blurring of the analytically motivated division between for-profit, nonprofit and public sectors in reality.” To explain these observations, Besley and Ghatak suggest that in the presence of incomplete contracts, optimal ownership is not a question of public versus private provision but simply should involve the party that values the created benefits most. Another interesting rationale provided by Besley and Ghatak (2007) identifies economies of scope (i.e., natural complementarities between private and public goods production, leading to cost asymmetries/advantages on the firm side) to be the decisive variable in determining the efficiency of impure public goods. The conclusion states that if economies of scope are absent, tasks should be segregated into specialized organizations (i.e., governments provide public goods and firms private ones). Otherwise, CSR might very well be optimal if governments or not-for-profit providers are unable to match CSR levels of public good provision due to opportunism, cost disadvantages (= economies of scope argument), or distributional preferences. All these findings are of immediate importance to those authorities involved in the mechanism design of public good provision.

Assuming that private and public good production is naturally bundled, the major trade-off between government regulation and CSR can be summarized as follows: While government regulation of firms may entail the production of optimal or excessive levels of public goods, the allocation of costs and benefits may be suboptimal due to the uniformity of public policy tools (i.e., firms have to charge higher prices and cannot sell to those consumers without sufficient willingness to pay for the impure public good anymore; this also denies those consumers the acquisition of the pure private good under consideration). On the other hand, CSR may achieve second best levels of the public good combined with distributional optimality inherent in the working of markets. Under special circumstances (e.g., if a government foregoes regulation because an absolute majority of voters does not have preferences for the public good), CSR can even Pareto improve total welfare by serving the minority of “caring” consumers (Besley & Ghatak, 2007). In sum, policy makers should take into account the systemic constraints of both public and corporate provision of public goods.

While analyzing CSR through a “public economics lens” offers important insights into welfare implications, efficiency, and comparative and normative questions regarding CSR and public policy, it does not shed sufficient light on the motivations behind CSR. Therefore, the next section develops a categorization of CSR along motivational lines and across theoretical frameworks. In short, CSR can be subclassified as either strategic, market-driven CSR, which is perfectly compatible with profit maximization and Milton Friedman’s view of the socially responsible firm, or as not-for-profit CSR that comes at a net monetary cost for share-holders. However, foregone profits (note that Reinhardt, Stavins, & Vietor [2008] define CSR in this spirit as sacrificing profits in the social interest) due to costly CSR need not be at odds with the principle of shareholder value maximization and do not automatically constitute moral hazard by managers if shareholders have respective intrinsic (social or environmental) preferences that substitute for utility derived from extrinsic (monetary) sources. Hence, any microeconomic explanation of CSR builds upon the recent advancement of new concepts of individual behavior in economics and the related departure from the classical homo oeconomicus assumption. In other words, the economic rationalization of CSR is closely linked to the extension of traditional individual rational choice theory toward a broader set of attitudes, preferences, and calculations.

From Whether to Why: Economics and the Evolutionary Understanding of CSR

Initial research into CSR was dominated by the question of whether firms do have any social responsibility other than employing people, producing goods or services, and maximizing profits. However, firms increasingly engaged in CSR activities that, at first sight, seemed to be outside its original, neoclassical boundaries. Hence, research shifted focus to why firms actually do CSR. Both questions, whether and why CSR, are intimately related and will be jointly addressed in this section.

Should firms engage in CSR? And if so, why (not)? In this respect, Milton Friedman (1970) examined the doctrine of the social responsibility of business and concluded that the only responsibility of business is to maximize profits (i.e., shareholder value), while goods or curtailment of bads based on public preferences or social objectives should be provided by governments endowed with democratic legitimation and the power to correct market inefficiencies (such as free riding or collective action problems). Based on the assumption of perfect government, this view suggested that CSR was a manifestation of moral hazard by managers (firm decision makers) toward shareholders and not only inefficient but also inconsistent with the neoclassical firm’s profit orientation. But rather than putting the discussion about CSR to a halt, Friedman’s thoughts provoked the search for an economic justification of CSR in line with neoclassical economics. The breakthrough came with the idea that CSR may actually be a necessary part of strategy for a profit-maximizing firm. In other words, profit maximization can be a motivation for CSR.

But how may CSR be integrated into the objective function of the profit-maximizing firm? The answer to this question builds upon the existence of preferences that are beyond those of the classical homo oeconomicus. Stakeholders as well as shareholders often are socially or, in general, intrinsically motivated, a fact that profit-maximizing firms cannot ignore as it directly affects demand in product markets and/or supply in labor markets. Furthermore, such preferences may induce governments to intervene in the market via regulation or taxation while fishing for votes (as stakeholders are at the same time voters and thereby determining who stays in power/government). In sum, social stakeholder preferences translate into some sort of action or behavior relevant to corporate profits. Therefore, CSR qualifies as part of a profit-maximizing strategy. CSR induced by demand side pressures or as a hedge against the risk of future regulation has been termed strategic CSR by Baron (2001), while McWilliams and Siegel (2001) refer to the same underlying profit orientation of CSR as a theory of the firm perspective.

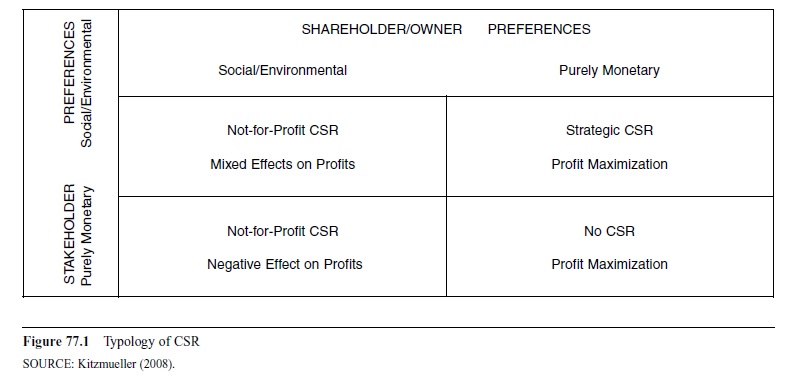

If shareholders have preferences allowing them to derive intrinsic utility equivalent to extrinsic, monetary utility, any resulting social or environmental corporate performance will constitute a nonstrategic form of CSR that is equally consistent with Friedman’s (1970) view of the firm. Here, the objective of the firm reflects the preferences of its owner(s) and therefore might involve a reduc-tion of profits or even net losses without breaking the rule of shareholder value maximization. So Friedman’s concept of CSR being equal to profit maximization has been confirmed and enriched by taking account of a new set of stakeholder and shareholder preferences. The result is a bipolar conception of CSR being either strategic or not for profit with varying implications for the financial performance of a firm. Figure 77.1 summarizes the four basic combinations of stakeholder and shareholder preferences and their implications for CSR. If shareholders are purely profit oriented, the firm should act strategically, maximize profits, and engage in CSR efforts only if stakeholders demand it. On the other hand, if shareholders care about corporate environmental and social conduct, CSR will always act as a corporate channel of contributing to public goods independent of stakeholder preferences. In this case, profit maximization is not the target, and nonstrategic firms may forego profits or incur losses to be borne by shareholders. The size of these losses depends, however, on stakeholders’ willingness to pay for and general attitude toward CSR.

At this point, a general discussion of the crucial role of individual preferences in the economic analysis of CSR is in order.

It was again Friedman (1970) who explicitly pointed out that to understand any form of social responsibility, it is essential to notice that society is a collection of individuals and of the various groups they voluntarily form (i.e., incentives, preferences, and motivations of individual share- and stakeholders determine organizational behavior). Stiglitz (1993, 2002) talks about new concepts to be taken into account when modeling individual behavior. Becker (1993) proposes an “Economic Way of Looking at Behavior,” stressing the importance of a richer class of attitudes, preferences, and calculations for individual choice theory. What Friedman, Stiglitz, and Becker have in mind is a new class of psychological and sociological ideas that recently entered microeconomic theory in general and the individual agent’s utility function in particular. Standard motivational assumptions have been expanded, and a literature on intrinsic (nonpecuniary) aspects of motivation has emerged. As the behavioral economics literature is rather extensive, only a few selected contributions that are believed to improve the understanding of CSR will be reviewed.

Figure 77.1 Typology of CSR SOURCE: Kitzmueller (2008).

Figure 77.1 Typology of CSR SOURCE: Kitzmueller (2008).

Three general determinants of individual utility can be distinguished. Contributions by Benabou and Tirole (2003, 2006) as well as Besley and Ghatak (2005) identify (1) extrinsic (monetary) preferences and (2) intrinsic (non-monetary) preferences as two main categories driving individual behavior via utility maximization. The intrinsic part of utility can be further divided into a (2.1) direct, non-monetary component determined independently of how others perceive the action or payoff and (2.2) an indirect component determined by others’ perception of respective action. (2.2) is frequently referred to as reputation. Assuming that individuals do derive utility from these three sources, economic theory can contribute to the analysis of strategic firm behavior such as CSR.

A first important insight is that intrinsic motivation can act as a substitute for extrinsic monetary incentives. Depending on the degree of substitutability, this affects both pricing through a potential increase in consumers’ willingness to pay as well as “incentive design” in employment contracting (subject to asymmetric information). In sum, when pricing products, firms may be able to exploit intrinsic valuation of certain characteristics by charging higher prices, while salaries might be lower than usual if employees compensate this decrease in earnings by enjoying a social or environmentally friendly workplace, firm conduct, or reputation in line with their expectations and personal preferences. Relevant theoretic works include Benabou and Tirole (2006), who find that extrinsic incentives can crowd out prosocial behavior via a feedback loop to reputational signaling concerns (2.2 above). This concern reflects the possibility that increased monetary incentives might negatively affect the agent’s utility as observers are tempted to conclude greediness rather than social responsibility when observing prosocial actions. Here the signal extraction problem arises because agents are heterogeneous in their valuation of social good and reputation, and this information is strictly private. Such considerations could influence not only employees, consumers, and private donors but also social entrepreneurs. Social entrepreneurs are individuals ready to give up profits or incur losses by setting up and running a CSR firm. (The opposite would be the private entrepreneur, who creates a firm if and only if its market value exceeds the capital required to create it.) CSR here expands the “social” individual’s opportunity set to do “good” by the option to create a CSR firm. Summing up, agents are motivated by a mixture of extrinsic and intrinsic factors, and therefore potential nonintended effects due to crowding between extrinsic and intrinsic motivators should be taken into account when designing optimal incentives (salaries, bonus payments, taxes, etc.).

So stakeholders demand CSR in line with their intrinsic motivation, and the key question that follows, this time with respect to alternative private ways of doing social good, asks why this corporate channel of fulfilling one’s need to do public good is used at all if there are alternatives such as direct social contribution (e.g., charitable donations or voluntary community work). From a welfare perspective, there should be some comparative advantage of CSR, something that makes it more efficient than other options. In an important paper, Andreoni (1989) compares different ways to contribute to social good and asks whether they constitute perfect or rather imperfect substitutes. Although the initial version compares public and private provision of public goods, the same analysis can be extended to compare various ways of private provision such as corporate and individual social responsibility. The answer then is straightforward. If warm glow effects (Andreoni, 1990) of individual (direct) altruistic giving exist, then investment into a CSR firm, government provision of public goods, and direct donations will be imperfect substitutes in utility and therefore imperfectly crowd out each other. In other words, a socially responsible consumer might not derive the same utility from buying an ethical product and from donating (the same amount of) money to charitable organizations directly. However, this analysis is unable to explain in more detail why individuals allocate a share of their endowment to do social good to CSR. A reasonable conjecture might be that people must or want to consume certain private goods but derive intrinsic disutility (e.g., bad conscience) from being connected to any socially stigmatized, unethical behavior or direct negative externality related to their purchase, seller, and/or use of the good or service. Furthermore, one should notice that social or environmental goods do not always directly or physically affect consumers but rather are feeding through to individual utility indirectly via intrinsic, reputational concerns (e.g., Nike’s connection to child labor in Asian sweatshops). However, these conjectures have yet to be sufficiently tested empirically.

A final economic puzzle worth thinking about is the one of causality between preferences and CSR—that is, opposite to the above assumed causality from preferences to firm behavior, CSR often has been connected with advertisement or public relations of firms, thereby suggesting that CSR eventually could determine or change preferences and ultimately individual behavior over time. While the management literature has approached these issues via the concept of corporate social marketing (Kotler & Lee, 2004), economists have been more cautious when it comes to endogenous preferences. As far as preference formation is concerned, Becker (1993) concluded that “attitudes and values of adults are … influenced by their childhood experiences.” Bowles (1998) builds the bridge from Becker’s “family environment” to markets and other economic institutions influencing the evolution of values, preferences, and motivations. Simon (1991) was among the first to argue that agency problems may be best overcome by attempting to change and ideally align preferences of workers and principals. The following real-world example shall illustrate the key issue here. Empirical evidence from the 1991 General Social Survey (outlined in Akerlof & Kranton, 2005, p. 22) suggests that workers strongly identify with their organization (i.e., employer’s preferences). In theory, this finding can be a result of matching (selection), reducing cognitive dissonance (psychology), or induced convergence of preferences (endogenous preferences). Given these alternatives, CSR could be either interpreted as a signal leading to matching of firms and individuals with similar preferences or alternatively used to align agents’ preferences over time. While the latter suggestion lacks theoretic or empirical treatment, the former potential matching role of CSR has been analyzed and will be outlined below.

It can be seen that a lot of open questions need to be answered when it comes to the mechanics of intrinsic motivation and social preferences within the human mind. Hence, further discussion of CSR focuses on strategic interaction between firms and stakeholders and treats the existence of intrinsic preferences as exogenously given.

Six Strategies Behind Strategic CSR

Six relevant economic frameworks within which strategic CSR can arise are discussed and linked to empirical evidence at hand: (1) labor markets, (2) product markets, (3) financial markets, (4) private activism, (5) public policy, and (6) isomorphism.

Labor Economics of CSR

CSR may alter classical labor market outcomes. Bowles, Gintis, and Osborne (2001) address the role of preferences in an employer-employee (principal-agent) relationship. The main idea is that employees might have general preferences such as sense of personal efficacy that are able to compensate for monetary incentives and therefore allow the employer to induce effort at lower monetary cost. Besley and Ghatak (2005) establish a theoretic framework to analyze the interaction of monetary and nonmonetary incentives in labor contracts within the nonprofit sector. They refer to not-for-profit organizations as being mission oriented and conjecture that such organizations (e.g., hospitals or universities) frequently are staffed by intrinsically motivated agents (think of a doctor or professor who has a nonpecuniary interest in the hospital’s or university’s success, i.e., saving lives or educating students). The main conclusion from their moral hazard model with heterogeneous principals and agents is that pecuniary, extrinsic incentives such as bonus payments and the agents’ intrinsic motivation can act as substitutes. In other words, a match between a mission-oriented principal and an intrinsically motivated agent reduces agency costs and shirking (i.e., putting lower effort when the principal cannot observe the work effort given by the agent but only the outcome of the work) and allows for lower incentive payment. As today many firms adopt missions (such as CSR activities) in their quest to maximize profits, this analysis may directly carry over to the private sector.

As opposed to Friedman’s (1970) concern that CSR is a general form of moral hazard (here moral hazard refers to managers or employees not acting in the best interest of shareholders or firm owners), Brekke and Nyborg (2004), based on Brekke, Kverndokk, and Nyborg (2003), show that CSR can actually reduce moral hazard in the labor market context. More precisely, CSR can serve as a screening device for firms that want to attract morally motivated agents. This view on CSR as a device to attract workers willing to act in the best interest of the principal is again based on the same substitutability of motivation due to CSR and related firm characteristics valued by the employees and high-powered incentives such as bonus payments.

Another labor market context that involves CSR and corporate governance is explored by Cespa and Cestone (2007). They conjecture that inefficient managers can and will use CSR (i.e., the execution of stakeholder protection and relations) as an effective entrenchment strategy to protect their jobs. CEOs and managers engage in CSR behavior in face of a takeover or replacement threat in order to then use such “personal” ties with stakeholders to bolster their positions within the firm (in other words, such managers establish themselves as key nodes linking the firm with strategic stakeholders, thereby gaining value independent of their true managerial capacity and performance). This discussion of the effect of corporate governance institutions on firm value leads to the conclusion that institutionalized stakeholder relations (as opposed to managers’ discretion) close this “insurance” channel for inefficient managers and increase managerial turnover and firm value. This finding clearly provides a rationale for the existence of special institutions such as ethical indices or social auditors and increased interaction between social activists and institutional shareholders in general. A similar approach to CSR is taken by Baron (2008), who links managerial incentives and ability with the existence of socially responsible consumers. He concludes that, given that consumers value CSR, when times are good, a positive correlation emerges between CSR and financial performance via the fact that high-ability managers tend to contribute more to CSR than low-ability ones, and the level of both, CSR and profits, is increasing in managers’ ability. In bad times, however, shareholders are not supporting social expenditure (for profits) anymore, high-ability managers become less likely to spend money on CSR as compared to low-ability ones, and the correlation between CSR and profits becomes negative. Baron’s work gives a first idea of the importance of consumer preferences in the determination of CSR efforts, which will be the subject of the following subsection.

CSR and Product Markets (Socially Responsible Consumption)

With regard to whether consumers really care about CSR, there is substantial empirical evidence supporting this assumption. Consumer surveys such as the Millennium Poll on Corporate Social Responsibility (Environics International Ltd., 1999) or MORI (http://www.ipsos-mori.com/ about/index.shtml) reveal that consumers’ assessment of firms and products as well as their final consumption decisions and willingness to pay depend on firms’ CSR records. In this respect, Trudel and Cotte (2009) find the equivalent to loss aversion in consumers’ willingness to pay for ethical products. According to their findings, consumers are willing to pay a premium for ethical products and buy unethical goods at a comparatively steeper discount. So there exists a channel from preferences and demand to CSR and/ or vice versa.

Consumer preferences may translate into demand for CSR and alter the competitive environment of firms as CSR can either act as product differentiation or even trigger competition with respect to the level of CSR itself. Bagnoli and Watts (2003) analyze competitive product markets with homogeneous, socially responsible consumers and find that CSR emerges as a by-product and at levels that vary inversely with the degree of competitiveness in the private goods market (competitiveness is reflected through both number of firms and firm entry). Bertrand (price) as opposed to Cournot (quantity) competition forces firms to reduce markups and hence limits their ability to use profits to increase CSR. This leads to reduced competitiveness in terms of product differentiation via CSR and hence to reduced overall CSR activity. In sum, there exists a trade-off between efficient provision of the private good and public good (i.e., Bertrand competition entails lower prices and lower levels of CSR than Cournot competition).

A more general framework is provided by Besley and Ghatak (2007), who find that Bertrand (price) competition in markets with heterogeneous demand for CSR leads to zero profits—that is, prices equal marginal costs and second best (suboptimal) levels of public good provision equivalent to results obtained in models of private provision (e.g., Bergstrom et al., 1986). Their analysis further allows validation of a whole array of standard results from the screening and public goods literature, among which, (a) the maximum sustainable level of CSR (under imperfect monitoring by consumers) is achieved when the firms’ incentive compatibility constraint binds—that is, at such a public good level the profits from doing CSR and charging a price premium are equivalent to profits from not producing the public good and still charging a price premium (cheating), given any probability (between 0 and 1) of being caught cheating and severely punished. (b) An exogenous increase of public good supply (e.g., by a government through regulation or direct production) perfectly crowds out competitive provision of CSR. (c) In the absence of government failure, governments are able to implement the first best Lindahl-Samuelson level of public good (i.e., the Pareto optimal amount, which is clearly above the levels markets can provide via CSR).

(d) However, when governments fail (e.g., due to corruption, capture, relative production inefficiencies, or distributional bias), CSR might generate a Pareto improvement vis-à-vis no production or government production of public good, while CSR and provision by nonprofits (e.g., NGOs) are identical unless one or the other has a technological (cost) advantage in producing the public good.

(e) Finally, a small uniform regulation in the form of a minimum standard (on public good levels) would leave the level of CSR unchanged and redistribute contributions from social to neutral consumers, while large regulatory intervention can raise supply of the public good to or above its first best level given that neutral consumers are willing to pay higher (than marginal cost) prices for the private good. These results highly depend on respective consumer preferences and their related willingness to pay for the private and public good (CSR) characteristics of the consumption good.

Arora and Gangopadhyay (1995) model CSR as firm self-regulation (i.e., voluntary overcompliance with environmental regulation) and assume that although consumers all value environmental quality, they vary in their willingness to pay a price premium for CSR, which is positively dependent on their income levels. Firms differentiate by catering to different sets of consumers; here choice of green technology acts as product positioning similar to the choice of product quality, and CSR is positively correlated with the income levels of either all consumer segments or the lowest income segment. If a minimum standard is imposed into a duopoly, it will actually bind on the less green firm while the other firm will overmeet the standard. CSR subsidies can have the same effect as standards, while ad valorem taxes (i.e., taxes on profits) always reduce output and CSR efforts by all firms.

An example of empirical work in this subfield is provided by Siegel and Vitaliano (2007), who test and confirm the hypothesis that firms selling experience or credence goods—that is, the good’s quality can only be observed after consumption (by experience, e.g., a movie) or is never fully revealed (credence, e.g., medical treatment or education)—are more likely to be socially responsible than firms selling search goods (i.e., goods where characteristics such as quality are easily verified ex ante). This lends support to the conjecture that consumers consider CSR as a signal about attributes and general quality when product characteristics are difficult to observe. From the firm perspective, CSR then can be used to differentiate a product, advertise it, and build brand loyalty. The advertising dimension of CSR is especially strong when social efforts are unrelated to business conduct. In Navarro (1988), corporate donations to charity are identified as advertisement, and CSR is meant to transmit a positive signal about firm quality/type. However, according to BeckerOlsen and Hill (2005), this signal might not necessarily be positive, as consumers are able to identify low-fit CSR as advertisement and tend to negatively perceive such CSR efforts as greediness of firms rather than genuine interest in social or environmental concerns.

CSR and Financial Markets (Socially Responsible Investment)

Investors also care about CSR, and firms competing for equity investment in stock markets will have to take that into account. Geczy, Stambaugh, and Levin (2005) put forward strong evidence of the increasing importance of CSR in financial markets. A new form of investment, so-called socially responsible investment (SRI), has come into being. SRI is defined by the Social Investment Forum (SIF, 2009) as an investment process that considers the social and environmental consequences of investments, both positive and negative, within the context of rigorous financial analysis. Social investors today include both private and institutional ones. More precisely, the U.S. Social Investment Forum (figures are taken from SIF, 2006) reports 10.8% of total investment under professional management in 2007 to be socially responsible (i.e., using one or more of the three core socially responsible investing strategies: screening, shareholder advocacy, and community investing). In Europe, the European Sustainable and Responsible Investment Forum (EuroSIF) identifies 336 billion euros in assets to be SRI. The trend points upward in most financial markets (e.g., in the United States, where SRI assets grew 4% faster than total assets and more than 258% in absolute terms between 1995 and 2005).

Recalling the typology of CSR (Figure 77.1), we know that investors either have or do not have social preferences. Neutral investors just have their monetary return on investment in mind and hence just care about firm profits. It follows that such investors will use SRI as an investment strategy only if SRI actually translates into higher returns on investment. So, SRI by neutral investors signals a comparative advantage in corporate financial performance (CFP). This conjecture and the related question of correlation and causality have attracted a lot of attention in the scarce empirical literature on CSR. A comprehensive survey is provided by Margolis and Walsh (2003). Taking into account 127 published empirical studies between 1972 and 2002, they find that a majority of these studies exhibit a statistically significant and positive correlation between CSR and CFP in both directions (i.e., causality is running from CFP to CSR and vice versa). However, there exist sampling problems, concerns about the validity of CSR and CFP measures and instruments, omitted variable bias, and the ultimate (and still unanswered) question of causality between CSR and CFP. A first attempt to address inconsistency and misspecification is the work by McWilliams and Siegel (2000), who regress firm financial performance on CSR and control for R&D investment. It follows that the upwards bias of the financial impact of CSR disappears and a neutral correlation emerges. In sum, further studies will have to clarify whether neutral investors should put their money into SRI and the underlying CSR effort qualifies as strategic.

Alternatively, SRI can be a way for social investors to enforce their preferences through a demand channel similar to the one consumers use. The group of social investors, however, can again be heterogeneous in the sense that there might be those for whom corporate giving is a close substitute for personal giving and those for whom it is a poor substitute (Baron, 2005). Small and Zivin (2005) enrich this setup by deriving a Modigliani-Miller theory of CSR, where the fraction of investors that prefers corporate philanthropy over private charitable giving drives CSR by firms attempting to maximize their valuation. A share constitutes a charity investment bundle matching social and monetary preferences of investors with those of the firm’s management. The main conclusion is that if all investors consider CSR and private charity as perfect substitutes, share prices and the aggregate level of philanthropy are unaffected by CSR. If they are imperfect substitutes and a sufficiently large fraction of investors prefers CSR over private charity (e.g., to avoid corporate taxation), a strictly positive level of CSR maximizes share prices and hence the value of a corporation.

CSR and Private Politics (Social Activism)

The existence and impact of social or environmental activists is intimately related with information asymmetries between companies and the outside world. The rationale of social activism is that the threat of negative publicity (revelation of negative information) due to actions by an unsatisfied activist motivates CSR. As soon as the activist is credible and has the ability to damage a firm’s reputation or cause substantial costs to the firm, the existence of such an activist is sufficient to integrate CSR as part of corporate strategy. The logic is comparable to the one of “hedging” against future risk in financial markets, but here the firm insures itself against a potential campaign by an activist. Baron (2001) explicitly adds this threat by an activist, who is empowered with considerable support by the public, to the set of motivations for strategic CSR. CSR is referred to as corporate redistribution to social causes motivated by (1) profit maximization, (2) altruism, or (3) threats by an activist. However, it can be argued that the existence of activism qualifies CSR as an integral part of profit maximization (i.e., motivation 3 fuses into 1).

The main insights from the analysis of CSR and social activism can be summarized as follows: First, CSR and private politics entail a direct cost effect depending on the competitive environment (i.e., the degree of competition is positively correlated with the power of an activist boycott and strengthens the ex ante bargaining position of the activist). On the other hand, CSR can have a strategic effect that alters the competitive position of a firm. What is meant here is that CSR can act as product differentiation (lower competition), take the wind out of the sails of any potential activist, and reduce the likelihood of being targeted in the future. This result roots in the assumption that the activist also acts strategically and chooses “projects” that promise to be successful (i.e., weaker firms are easier targets). Finally, the existence of spillover effects from one firm to other firms or even the whole industry can act as an amplifier to activist power, on one hand, and motivation for concerted nonmarket action by firms in the same industry, on the other (e.g., voluntary industry standards).

Baron (2009) assumes that citizens prefer not-for-profit (morally motivated) over strategic CSR. If signaling is possible, morally motivated firms achieve a reputational advantage, and social pressure will be directed toward strategic firms. If citizens are not distinguishing, morally motivated firms are more likely targeted as they are “softer” targets in the sense that an activist is more likely to reach a “favorable” (i.e., successful from activist objective’s point of view) bargain with such a firm. However, the distinction between strategic and not-for-profit CSR can be extremely difficult, subtle, and based on perception rather than facts. Recent work by marketing scholars lends support to this proposition. Becker-Olsen and Hill (2005) find that consumers form their beliefs about CSR based on perceived fit and timing of related efforts (i.e., a high fit between CSR and the firm’s business area as well as proactive rather than reactive social initiatives tend to align consumers’ beliefs, attitudes, and intentions with those of the strategic firm). Finally, if activists differ in ability, Baron shows that high-quality activists attract greater contributions and then are more likely to identify and target strategic firms, while the opposite holds for low-quality activists.

CSR and Public Politics (Regulation)

CSR is defined as corporate social or environmental effort beyond legal requirements. Then how can public politics and laws actually stimulate CSR? This time, it is the threat of future laws and regulations and the adjustment costs and competitive disadvantage they could entail that act as an incentive to hedge against such an event and build a strategic “buffer zone” via CSR. Again, by doing CSR, firms not only are “safe” in the event of regulation but also might discourage government intervention. This last point has been addressed under the label of crowding out. The analysis here focuses on whether market provision of public goods and public provision are substitutes or complements and how they might interact (Bergstrom et al., 1986). From a policy perspective, it seems to be important not only to understand interaction between public provision and CSR but also to consider CSR itself as a potential target for novel policies aiming to stimulate corporate provision of public goods.

Calveras et al. (2007) study the interplay between activism, regulation, and CSR and find that private (activism) and public (regulatory) politics are imperfect substitutes. It is emphasized that when society free rides on a small group of activist consumers, loose formal regulation (voted for by the majority of nonactivists) might lead to an inefficiently high externality level, where activist consumers bear the related cost via high prices for socially responsible goods. This conclusion draws attention to another relevant correlation—namely, between regulation and political orientation. Consumers are also voters, and not only firms but also governments want to signal their type (i.e., whether they value environmental or social public goods). As governments signal their future intentions and policy stances through legislation or regulation and firms through CSR, the potential competition and related interaction between regulation and CSR constitute an important subject of further investigation.

Empirically, Kagan, Gunningham, and Thornton (2003) address the effect of regulation on corporate environmental behavior. They find that regulation cannot fully explain differences in environmental performance across firms. However, “social license” pressures (induced by local communities and activists) as well as different corporate environmental management styles significantly add explanatory power. In sum, regulation matters, but variation in CSR is also subject to the antagonism between social pressure and economic feasibility.

Isomorphism

Here, the incentive to do CSR roots in isomorphic pressures within geographic communities or functional entities such as industries. Community isomorphism refers to the degree of conformity of corporate social performance in focus, form, and level within a community. It is the institutional environment and commonly (locally) accepted norms, views, and values that might discipline firms into certain social behavior. Institutional factors that are potentially shaping the nature and level of CSR in a community include cultural-cognitive forces, social-normative factors, and regulative factors. Marquis, Glynn, and Davis (2007) use an institutional theoretic setting and identify community isomorphism as a potential explanatory variable for empirical observations concerning CSR. Isomorphic pressures may also arise within industries and may lead to industry-wide self-regulatory activities.

Conclusion

From an economic point of view, a fundamental understanding of CSR is emerging. Based on a new set of social or environmental stakeholder preferences, CSR can be fully consistent with a profit- and/or shareholder value-maximizing corporate strategy. It qualifies as strategic behavior if consumers, investors, or employees have relevant social or environmental preferences and if these preferences translate into action with direct or indirect monetary effects for the firm. Direct consequences include the firm’s ability to charge price premia on CSR comparable to premia on product quality, as well as the potential lowering of wages for “motivated” employees, who substitute the utility they gain from working for and within a responsible firm/environment for monetary losses due to lower salaries. Firms’ profits may be indirectly affected by CSR in the sense that CSR can help avoid competitive disadvantages or reputation loss arising in situations where stakeholder action (consumption or activism) depends on social or environmental corporate conduct. Empirical evidence lends support to most of these incentives for strategic CSR; however, rigorous statistical analysis is still in an infant state and subject to various problems, including measurement error, endogeneity, and misspecification.

See also:

Bibliography:

- Akerlof, G. E., & Kranton R. E. (2005). Identity and the economics of organization. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 9-32.

- Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97, 1447-1458.

- Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100, 464-477.

- Arora, S., & Gangopadhyay, S. (1995). Toward a theoretical model of voluntary overcompliance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 28, 289-309.

- Bagnoli, M., & Watts, S. G. (2003). Selling to socially responsible consumers: Competition and the private provision of public goods. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 12, 419-445.

- Baron, D. P. (2001). Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 10, 7-45.

- Baron, D. P. (2005). Corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship (Stanford GSB Research Paper No. 1916). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Baron, D. P. (2008). Managerial contracting and CSR. Journal of Public Economics, 92(1-2), 268-288.

- Baron, D. P. (2009). A positive theory of moral management, social pressure and corporate social performance. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18, 7-43.

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 101, 385-409.

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., & Hill, R. P. (2005). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59, 46-53.

- Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2003). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 489-520.

- Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and pro-social behavior. American Economic Review, 96, 1652-1678.

- Bergstrom, T., Blume, L., & Varian, H. R. (1986). On the private provision of public goods. Journal of Public Economics, 29, 25-49.

- Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2001). Government versus private ownership of public goods. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1343-1372.

- Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2005). Competition and incentives with motivated agents. American Economic Review, 95, 616-636.

- Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2007). Retailing public goods: The economics of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 1645-1663.

- Bowles, S. (1998). Endogenous pReferences: The cultural consequences of markets and other economic institutions. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 75-111.

- Bowles, S., Gintis, H., & Osborne, M. (2001). Incentive-enhancing pReferences: Personality, behavior and earnings. American Economic Review, 91(2), 155-158.

- Brekke, K. A., Kverndokk, S., & Nyborg, K. (2003). An economic model of moral motivation. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1967-1983.

- Brekke, K. A., & Nyborg, K. (2004). Moral hazard and moral motivation: Corporate social responsibility as labor market screening (Memorandum N025). Oslo, Norway: Department of Economics, University of Oslo.

- Buchanan J. M. (1999). The demand and supply of public goods. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund. Retrieved from http://www .econlib.org/Library/Buchanan/buchCv5c1.html

- Calveras, A., Ganuza, J. J., & Llobet, G. (2007). Regulation, corporate social responsibility, and activism. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 16, 719-740.

- Cespa, G., & Cestone, G. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and managerial entrenchment. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 16, 741-771.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2005, January). The importance of corporate responsibility (White paper). Retrieved from http://graphics.eiu.com/files/ad_pdfs/eiuOracle_Corporate Responsibility_WP.pdf

- Environics International Ltd. (1999, September). Millennium poll on corporate responsibility, in cooperation with The Prince of Wales Trust.

- European Commission. (2009). Corporate social responsibility (CSR). Available at http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/ sustainable-business

- Fleishman-Hillard & the National Consumers League. (2005). Rethinking corporate social responsibility. Retrieved from http://www.csrresults.com/FINAL_Full_Report.pdf

- Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times, pp. 32-33, 122, 126.

- Geczy, C., Stambaugh, R., & Levin, D. (2005). Investing in socially responsible mutual funds (Working paper). Philadelphia: Wharton School of Finance.

- Kagan, R. A., Gunningham, N., & Thornton, D. (2003). Explaining corporate environmental performance: How does regulation matter? Law and Society Review, 37, 51-90.

- Kitzmueller, M. (2008). Economics and corporate social responsibility (EUI ECO Working Paper 2008-37). Available at http://cadmus.eui.eu

- Kotchen, M. J. (2006). Green markets and private provision of public goods. Journal of Political Economy, 114, 816-845.

- Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2004, Spring). Best of breed. Stanford Social Innovation Review, pp. 14-23.

- Margolis, J. D., & Walsh, J. (2003). Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 268-305.

- Marquis, C., Glynn, M. A., & Davis, G. F. (2007). Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Academy of Management Review, 32, 925-945.

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. S. (2000). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 603-609.

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. S. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26, 117-127.

- Navarro, P. (1988). Why do corporations give to charity? Journal of Business, 61, 65-93.

- Reinhardt, F. L., Stavins, R. N., & Vietor, R. H. K. (2008). Corporate social responsibility through an economic lens (NBER Working Paper 13989). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Rose-Ackerman, S. (1996). Altruism, nonprofits and economic theory. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 701-728.

- Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2008). Globalization and corporate social responsibility. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 413-431). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Siegel, D. S., & Vitaliano, D. F. (2007). An empirical analysis of the strategic use of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 16, 773-792.

- Simon, H. A. (1991). Organizations and markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(2), 25-44.

- Small, A., & Zivin, J. (2005). A Modigliani-Miller theory of altruistic corporate social responsibility. Topics in Economic Analysis and Policy, 5(1), Article 10.

- Social Investment Forum. (2006). 2005 report on socially responsible investing trends in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.socialinvest.org/pdf/research/Trends/2005%20 Trends%20Report.pdf

- Social Investment Forum. (2009). The mission in the marketplace: How responsible investing can strengthen the fiduciary oversight of foundation endowments and enhance philanthropic missions. Available at http://www.socialinvest.org/resources/pubs

- Stiglitz, J. E. (1993). Post Walrasian and post Marxian economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7, 109-114.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2002). Information and the change in the paradigm in economics. American Economic Review, 92, 460-501.

- Trudel, R., & Cotte, J. (2009). Is it really worth it? Consumer response to ethical and unethical practices. MIT/Sloan Management Review, 50(2), 61-68.

- Vogel, D. (2005). The market for virtue: The potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- World Bank. (n.d.). Financial and private sector development. Retrieved from http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/economics.nsf/content/ csr-intropage

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.