This sample Economics of Education Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the economics research paper topics.

Economics is a study of making choices to allocate scarce resources—what to produce, how to pro’ duce, and for whom to produce. With education being one of the top social priorities to compete for scarce resources, economic analysis on returns of education, the optimal allocation of education resources, and evaluation of education policies has become increasingly important. In addition to the theoretical development and empirical applications of human capital theory, different areas of economics have also applied to education issues, such as the use of the economics of production to study the relation between education inputs and outputs.

Since the release of the 1983 National Commission on Excellence in Education report A Nation at Risk, the U.S. government has initiated different education reforms to improve failing student performance. In recent years, rich data sets (often longitudinal) have become available from different education policy experiments—for example, voucher programs in Milwaukee and accountability policies in different states. Research that takes advantage of these policy experiments has shed some light in the current education debate by providing empirical evidence of the impact of different policies and suggestions for policy design.

In this research paper, the human capital theory and an alternative screening hypothesis are first introduced to provide some theoretical background in the area. Next, the impact of various education inputs on student performance is discussed to apply the production theory on education and to highlight some of the empirical challenges in evaluating the impact of key factors in education. Then, theoretical and empirical evidence on school choice and accountability policies in the elementary and secondary school markets is described to highlight the policy relevance of the field.

Theory

Human Capital Theory

Education is often regarded as one of the main determinants in one’s labor market success. The primary model used to measure the returns to education in the field is the human capital theory. Drawing an analogy to the investment theory of firms, each worker is paid up to his or her marginal productivity—the increment of output to a firm when an additional unit of labor input is employed. Human capital theory postulates that education is made as human capital investment to improve one’s productivity and earnings.

The essence underlying human capital theory can be traced back to Adam Smith’s classic theory of equalizing differentials, in which the wages paid to workers should compensate for various job characteristics. The modern human capital theory, building on the seminal work of Theodore Schultz (1963), Gary Becker (1964), and Jacob Mincer (1974), has drawn attention to conceptualizing the benefits of education and to modeling education as a form of investment in human capital.

As a first step to calculating the rate of returns to education, Schultz (1963) categorized a list of education benefits, including the private benefits in terms of wages and the social benefits that are accrued to the economy as a whole (e.g., research and development to sustain economic growth and better citizenship). In calculating the costs of education, in addition to the direct costs of tuition, transportation, books, and supplies, the indirect costs of forgone earnings— the opportunity costs incurred while acquiring the human capital during schooling—should also be included.

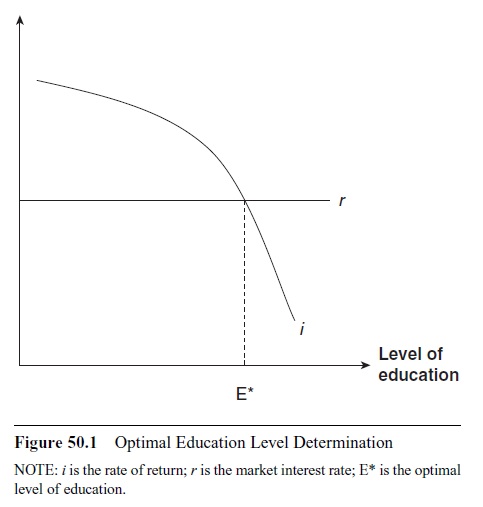

Introduced by Becker (1964), one way to determine the optimal level of education is to compare the internal rate of return (i) earned by acquiring that level of education and the market rate of interest (r) in financing to acquire that level of education. The internal rate of returns to education corresponds to the implicit rate of return earned by an individual acquiring that amount of education, and the market rate of interest represents the opportunity cost of financing the investment required to obtain the amount of education. Because of diminishing returns, the present value of marginal benefits of education generally declines with years of education. The present value of marginal costs (direct cost and the opportunity cost of forgone earnings), on the other hand, generally increases with years of education. The combined actions of marginal benefits and marginal costs of education result in a falling internal rate of return when education attainment rises. As a simple illustration, assuming a constant cost of borrowing in the capital market, Figure 50.1 shows that one will continue to invest in education as long as the internal rate of return (i) exceeds the market rate of interest (r) and that the optimal equilibrium education (E*) level has been attained when i = r.

Estimating the Rate of Returns to Education

To empirically estimate the rate of returns to education, cross-sectional data on earnings of different individuals at a point in time can be compared, and the differences in earnings can be attributed to differences in the levels of education after accounting for other observable differences. Mincer (1974) developed a framework to estimate the rate of returns to education in the form of the human capital earnings function as follows:

log Yi = a + rS + bX + cX2 + e, (1)

where y are the earnings of individual i. S represents the years of education acquired, X represents individual’s potential experience that is usually approximated by X = age — S — 6, and e is the stochastic term.

Figure 50.1 Optimal Education Level Determination

Figure 50.1 Optimal Education Level Determination

The Mincer (1974) model is widely used to estimate returns of schooling, and the estimate r can be interpreted as the rate of returns to education when assuming that each additional year of education has the same effect on earnings and the years of schooling are measured accurately. Using the U.S. Census data, James Heckman, Lance Lochner, and Petra Todd (2006) showed that the data from recent U.S. labor markets do not support the assumptions required for interpreting the coefficient on schooling as the rate of returns to education; the review calls into question using the Mincer (1974) equation to estimate rates of returns to education. To better fit the data in modern labor markets, many studies have extensions and modifications of the original Mincer equation—for example, allowing wage premiums when one completes elementary school in Grade 8, high school in Grade 12, and college after 16 years of completed education (the sheepskin effect), as well as incorporating other interaction terms or nonlinearities into the earnings equation.

A growing literature has also attempted to measure the causal effect of schooling by addressing the concern of ability bias in standard earnings equations. By assuming that, because of their same genetic makeup, identical twins’ innate ability would be the same, Orley Ashenfelter and Cecilia Rouse (1998) estimated the rate of returns to education on a large sample of identical twins from the Princeton Twins Survey. Their results confirm that there is ability bias in the standard estimation, and once the innate ability is controlled for, the estimate of the returns to education is lowered.

Screening

The human capital theory emphasizes the role of education in enhancing one’s productivity. An alternative model based on the work of Kenneth Arrow (1973) and Michael Spence (1973) argued that education plays a role as a signal of workers’ productivity when productivity is unknown before hiring because of imperfect information. The assumption is that if the individuals with higher ability have lower costs of acquiring education, they are more likely to acquire a higher level of schooling. In such a case, the level of education one possesses can act as a signal to employers of one’s productivity, and individuals will choose an education level to signal their productivity to potential employers.

It is empirically difficult to distinguish between the human capital theory and the screening hypothesis because high-ability individuals will choose to acquire more education under either theory. In an attempt to contrast the two models, Kevin Lang and David Kropp (1986) examined U.S. enrollment data and compulsory attendance laws from 1910 to 1970. Under the human capital theory, the effect of an increase in minimum school-leaving age should be apparent only among individuals that have optimal years of education lower than the minimum school-leaving age. Under the signaling model, the increase in minimum school-leaving age will also affect individuals that are not directly affected under the policy in the human capital theory. The reason is that a rise of the minimum school-leaving age from t to t + 1 would decrease the average ability level of individuals with t + 1 years of education. To signal higher ability, the high-ability individuals will choose to stay in school for t + 2 years. Therefore, the human capital theory and the signaling theory would yield different implications for the changes in compulsory attendance laws. Lang and Kropp’s analysis showed that enrollment rates did increase beyond those directly affected by the rise in minimum school-leaving age

Thus far, empirical evidence in the area is still limited, and the results have not been conclusive in determining the role of the two theories in education investment decisions. On one hand, the pure signaling model cannot explain the investment decision in professional education programs such as medical science or law because it is only through the professional programs that one can accumulate the knowledge and skills necessary for those occupations; on the other hand, it is impossible to discount the value of signaling completely from the empirical data. Given the important role of education in our society, both theories contribute in explaining the motivation of education investment decisions, and the current literature suggests that the importance of each theory might differ by the level and program in which an individual enrolls.

Education Production Function

In the production theory, a production function typically indicates the numerical function by which levels of inputs are translated into a level of output. Similarly, an education production function is usually a function mapping quantities of measured inputs in schooling (e.g., school resources, student ability, and family characteristics) to some measure of school output, like students’ test scores or graduation rates. A general education production function can be written as follows:

Tit=f(Sit,Ai,Fit,Pit) (2)

where Tit is the measured school output, such as test scores of student i at time t. For the inputs in the production function, S measures resources received by students at schools that are affected by school expenditure, teacher quality, class size, as well as curriculum planning and other school policies. A denotes the innate ability of a student, F measures the family background characteristics that are related to student education attainment, and P measures peer effects from classmates and close peers.

Many empirical studies have attempted to measure the impact of school resources on performance because school inputs can be more directly affected by policies targeted to improving student performance. One of the earliest studies in the area is the landmark 1966 Equality of Educational Opportunity report led by James S. Coleman. Aiming to document the different quality of education received by different populations in the United States in response to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the author collected detailed information on schools, teachers, and students. One of the most controversial conclusions from the report is that measurable characteristics of schools and teachers played a smaller role in explaining the variation of student performance compared to family characteristics. Though the Coleman report’s interpretation has been criticized from the regression framework (e.g., in Eric Hanushek and John Kain, 1972), the report remains a benchmark study in assessing education outcomes.

In a widely-cited paper, Hanushek (1986) surveyed the literature on the impact of school inputs and concludes that there is no evidence that real classroom resources (including teacher-pupil ratio, teacher education, and teacher experience) and financial aggregates (including teacher salary and expenditure per pupil) has a systematic impact in raising student performance. Reviewing research with new data and new methodologies in a follow-up, Hanushek (2006) maintained that the conclusion about the general inefficiency of resource usage in public schools is still warranted; further, he suggested that more research is needed in the area to understand when and where resources are most productively used.

Class Size

A popular policy proposal is to reduce class size to improve student performance. With smaller class sizes, students can have more personal interactions with teachers during class time. However, as pointed out by Caroline Hoxby (2000), measuring the impact of class size has been difficult because the greater part of class size variation documented in administrative data “is the result of choice made by parents, schooling providers, or courts and legislatures” (p. 1240). The observed variations in class sizes, therefore, are correlated with some unobservable factors that might be correlated with student performance.

To ascertain the effect of class size reduction, the Tennessee Department of Education conducted a 4-year longitudinal class size study, the Student Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR). The cohort of students who entered kindergarten in the 1985 to 1986 school year participated in the experiment through third grade. A total of 11,600 children were involved in the experiment over all 4 years. The students were randomly assigned into one of three interventions: small class (13 to 17 students per teacher), regular class (22 to 25 students per teacher), and regular-with-aide class (22 to 25 students per teacher with a fulltime teacher’s aide). Classroom teachers were also randomly assigned to the classes they would teach. The class size cutoffs were designed following the study conducted by Gene Glass and Mary Smith (1979). They summarized the findings on the performance impact of class size from 77 studies comparing student performance in different class sizes and concluded that the greatest gains in achievement occurred among students who were taught in classes of 15 students or fewer.

The STAR project provides an opportunity to study the causal effect of class size given that the students are assigned to different class size randomly to avoid the endo-geneity problem of the class size variable. Alan Krueger

(1999) controlled for observable student characteristics and family background and found that relative to the standard deviation of the average percentile score, students in smaller classes performed better than those in the regular classes (both with and without an extra teaching aide). The effect sizes are 0.20 in kindergarten, 0.28 in first grade, 0.22 in second grade, and 0.19 in third grade, which suggest that the main benefit of small class size tended to concentrate by the end of the first year. In light of this finding, Krueger suggested that small class size “may confer a onetime, ‘school socialization effect’ which permanently raises the level of student achievement without greatly affecting the trajectory” (p. 529).

Using an alternative measurement approach, Hoxby (2000) exploited the natural variation in population size from a long panel of enrollment data in Connecticut school districts. Similar to Project STAR, the class size variation that resulted from cohort size variation is exogenous in the estimation because class sizes are not driven by choices of parents or the school authority. However, using this natural population variation in class size, the analysis found no significant impact of class size on student performance.

Family Factors

In addition to school resources, innate ability is an important contributor in student performance that is often unobservable in data analysis. To further complicate the analysis, family background, especially parental education, is often correlated with unobserved student ability. While reviewing the literature on school resources and student outcomes, David Card and Krueger (1996) pointed out that the presence of omitted variables might bias the relation between school resources and student outcomes because children from better family backgrounds are likely to attend schools with more resources.

Having some family controls in the empirical analysis is important to control for the influence family factors might have on student outcomes. Nonetheless, there has been limited evidence identifying the impact of family factors on student performance separately. Take family income as an example: Most studies can show only a suggestive correlation between student outcomes and family income but not of a causal relationship between family income and student outcome (Mayer, 1997). Family income is likely to suffer from the problem of endogeneity under such a reduced-form regression model because children growing up in poor families are likely to face other adverse challenges that would continue to affect their development even if family income were to increase. To address the issue of endogeneity, different papers have attempted to isolate the exogenous variation of income using different research designs. Gordon Dahl and Lance Lochner (2008) exploited the income shocks generated by the large, nonlinear changes in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the past two decades. Their analysis found a positive impact of income on student mathematics and reading scores, and the effects were stronger for children of younger ages. Exploiting the policy variation in child benefit income among Canadian provinces, Kevin Milligan and Mark Stabile (2009) also showed that child benefit programs in Canada had significant positive effects on different measures of child outcomes. More research in the area is still needed to understand the impact of family factors and to prescribe relevant policy recommendations.

Peer Effects

A distinct feature of the education production function is that there is a public good component in student performance. Classroom teaching simultaneously provides benefits to more than one student at the same time, and the learning experience of one student is being affected by the average quality of his or her classmates (peer effects). Edward Lazear (2001) explicitly modeled the negative externalities created from the disruptive behavior of one student on all other classmates and provided the theoretical intuition to reconcile the mixed results documented in the class size reduction analysis. In particular, the model implied that class size effects are more pronounced in smaller classes for students with special needs or from disadvantaged populations.

Empirical evidence in identifying peer effects, however, has been rather limited. Charles Manski (1993) pointed out that analyses from standard approaches that regress students’ outcomes on peer outcomes cannot properly isolate peer effects from the selection effect, in which it is difficult to separate a group’s influence on an individual’s outcome from the individual’s influence on the group—the reflection problem. To put it simply, the reflection problem occurs when the performance of Student A is influenced by the presence of Student B, and vice versa. Another challenge in identifying peer effects empirically is that peers are rarely assigned randomly. Parents are likely to select neighborhoods through residential location to associate with good peers in good neighborhoods with good schools. A positive correlation between peer and individual might reflect this unobserved self-selection instead of any direct impact of peers on student performance.

The effect of increased sorting from increased school choice initiatives is often discussed in the choice policy debate. When more choice is given to parents, students remaining in the public school will suffer if the better students choose to leave the public school and switch to the alternative and thereby lower the peer quality remaining in the public school. The impact of sorting based on out-comes is discussed in the school choice section.

Education Policy

To improve the efficiency and effectiveness of public schools, a variety of reform strategies have been proposed on the policy front. These include restructuring the school organization and decision-making process, improving accountability, and providing more choice among schools as reflected in policies such as open enrollment programs that increase choice in the public school system or private school vouchers and tuition tax credits between public and private schools. In this section, the policy implications and empirical evidence on school choice and accountability measures are discussed to highlight the policy relevance of economic analysis in education.

School Choice

The promotion of choice among schools through the use of financing mechanisms such as vouchers and tuition tax credits has a long history. Milton Friedman’s original essay on the government’s role in education, published in Capitalism and Freedom (1962, chap. 6), is often regarded as the source that reinvigorated the modern voucher movement. In the essay, Friedman advocated the use of government support for parents who chose to send their children to private schools by paying them the equivalent of the estimated cost of a public school education. One of the key advantages of such an arrangement, he argued, would be to permit competition to develop and stimulate improvement of all schools.

The concepts of choice and competition are closely related and tend to be used interchangeably in this area of research. Yet, as defined in Patrick Bayer and Robert McMillan (2005), there is a clear distinction between the two, with choice relating to the availability of schooling alternatives for households and competition measuring the degree of market power enjoyed by a school. Typically, one would expect a positive correlation between the two, with an increase in choice being associated with an increase in competition. According to the standard argument, increased competition will force public schools to improve efficiency in order to retain enrollment. Yet in principle, increased choice need not always improve school performance, as illustrated in a model developed by McMillan (2005). His model showed that rent-seeking public schools could offset the losses from reduced enrollment by cutting costly effort.

Using public money in the form of vouchers or tax credits to support private schools is perhaps one of the most contentious debates in education policy today. School choice advocates claim that increasing school choice could introduce more competition to the public system to improve overall school quality and increase the access to alternative schools for low-income students, minority students, or both, who would otherwise be constrained to stay in the public system. Opponents argue that it is inappropriate to divert funds from the already cash-strapped public system because it would have a detrimental impact on school quality. According to the opponents’ view, voucher or tax credit policy is likely to benefit only affluent families who could afford the additional cost of attending private schools given that the vouchers and tax credits are unlikely to cover the total cost of attending private schools.

Despite the controversy of school choice debate, there are now a number of U.S. states implementing various forms of school choice programs: Arizona, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Puerto Rico have adopted some forms of tax credit, deductions, or both; Colorado, the District of Columbia, Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin have publicly funded school voucher programs in place; and Maine, Vermont, and New York have voucher programs funded by private organizations.

Empirical studies that examine the effect of private schools as well as different choice programs are discussed to highlight the important role of economic analysis in evaluating policy programs and the challenge in identifying the school choice impact.

The Effects of Private Schools

One strand of the choice literature has focused on public versus private provision, to see whether student outcomes differ across sectors, controlling for student type. In practice, students self-select into public or private schools, and this nonrandom selection might bias the performance effect in a comparison of outcomes between public and private schools since private school students may be unobservably better.

In an early study, Coleman, Thomas Hoffer, and Sally Kilgore (1982) used data from the High School and Beyond Survey of 1980 and showed that Catholic schools were more effective than public schools. Jeffrey Grogger and Derek Neal (2000) used the National Educational Longitudinal Survey of 1988, which allowed analysis of secondary school outcomes conditional on detailed measures of student characteristics and achievement at the end of elementary school. They found achievement gains in terms of high school graduation rates and college attendance from Catholic schooling, and the effects were much larger among urban minorities. Given the difficulty in controlling for selection bias in the measurement approach, only suggestive evidence on positive private school effects can be drawn from these studies.

Small-Scale Randomized Voucher: The Milwaukee Experiment

Wisconsin was the first U.S. state to implement a school voucher program, the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, to low-income students to attend nonreligious private schools in 1990. Only students whose family income was at or below 1.75 times the national poverty line were eligible to apply for the vouchers. The number of successful applicants was restricted to 1% of the Milwaukee public school enrollment in the beginning of the program and was later raised to 1.5% in 1994 and 15% in 1997. One thing worth noting in the Milwaukee program is that only nonreligious private schools are allowed to participate in the program.

Using the normal curve equivalent reading and math scores from the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS), which was administered to the Choice students every year and in Grades 2, 5, and 7 for students in the Milwaukee public schools, Rouse (1998) compared the test scores of Choice students with those of unsuccessful applicants and other public school students. The sample consisted of African American and Hispanic students who first applied in the years 1990 to 1993 for the program, and a matching cohort was drawn from the public student data with valid test scores for comparison. Rouse’s results showed that the voucher program generated gains in math scores, and students selected for the voucher program scored approximately two extra percentage points per year in math when compared with unsuccessful applicants and the sample of other public school students. In contrast, there was no significant difference in reading scores.

Tuition Tax Credit: Ontario, Canada

In 2001, the provincial government of Ontario, the most populous province in Canada, passed the Equity in Education Tax Credit Act (Bill 45), which led to an exogenous increase in choice between public and private schools. The tax credit applied to the first $7,000 of eligible annual net private school tuition fees paid per student. Although 10% of eligible tuition fees could be claimed for the tax year 2002, a 50% credit rate was scheduled to be phased in over a 5-year period, resulting in a maximum tax credit of $3,500 when the program was fully implemented in 2007, which was a comparable amount to that offered in the Milwaukee experiment (about $3,200 in 1994 to 1995). The tax credit was large in scope because about 80% of private schools participated in the program, irrespective of their religious orientation. In 2003, the credit was switched off unexpectedly because of a change in the provincial political party in power.

Taking advantage of this unique opportunity to study a large-scale increased choice experiment in North America, Ping Ching Winnie Chan (2009) examined the Grade 3 standardized test (an annual assessment administered by the Education Quality and Accountability Office in Ontario) of Ontario public schools before and after the introduction of the tax credit policy. The empirical evidence indicates that the impact of competition was positive and significant in 2002 to 2003 (the year the tax credit was in full effect). The average proportion of students attaining the provincial standard was found to be about two percentage points higher in districts with greater private school presence—districts where competition from private schools would be higher because of the tax credit. The Ontario experience provides evidence that increasing private school choice could help public schools to improve their performance.

Choice Within the Public System

In addition to an increase in school choice from private schools, there are other forms of choice within the public system—for example, open enrollment policies, magnet schools, and charter schools. Students in North America typically attend a neighborhood public school assigned within the school attendance boundary, and the application to out-of-boundary schools varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Open enrollment policies allow a student to transfer to another school either within or outside his or her school attendance area. This form of choice is indeed the most prominent form of choice available to students in the public system. Magnet schools are schools operated under the public system, but they exist outside of the zoned boundaries and offer academic or other programs that are different from the regular public schools to attract enrollment. Charter schools, on the other hand, are not subjected to the administrative policies within the public system even though they are also publicly funded. The charter documents the school’s special purpose and its rules of operation and will be evaluated by the declared objectives in the charter. In the United States, there are about 200 charter schools, mostly situated in Minnesota and California, and in Canada, Alberta is the only province with charter schools. The magnet schools and the charter schools aim to provide more diversity within the public system to meet the needs of students.

Open Enrollment Policy: Chicago Public Schools

In Chicago, students have more flexibility in their high school selection and may apply to schools other than their neighborhood schools when space is available through the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) open enrollment policy. The take-up rate of the policy among Chicago students is quite high, and more than half of the students in CPS opt out of their neighborhood schools.

Using detailed student-level panel data from CPS, Julie Cullen, Brian Jacob, and Steven Levitt (2005) compared the outcomes of those who did versus those who did not exercise choice under the open enrollment program. Students opting out of their assigned high schools (i.e., those exercising choice) were found to be more likely to graduate compared to those who remained in their assigned schools. An important insight in their study, though, is the presence of potential selection bias in the sample of students who take advantage of the choice program. If the more motivated students are more likely to opt out of local schools and to fare better academically than students with lower motivation, then opting out may be correlated with higher completion rate. This calls into question whether to interpret the higher education outcomes as an effect from the school choice program itselfor from the selection bias in motivation or other unobservable characteristics among the students who opted out.

As mentioned, one of the important issues in the school choice literature relates to the performance impact from increased student sorting. Although competition varies, the mix of students between public schools and alternative schools would also vary. Thus, in a more competitive environment, the average ability of students in public schools may be systematically different from students in public schools operating in a less competitive environment. When school choice increases, productivity responses from schools and sorting effects due to changes in the mix of students are likely to operate together. It is an empirical challenge to separate the effects of sorting from productivity responses, and more research in the area is still required in this direction.

Accountability

Much of the earlier debate in U.S. educational policy for raising performance concentrates on providing more resources to the system, such as increasing educational expenditures, reducing pupil-teacher ratios, or supporting special programs to target students with different needs. As performance responses to these policy initiatives have shown to be less than encouraging (see Hanushek, 1986), federal policy since the 1990s has moved to emphasize performance standards and assessments. Since the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2001, all states are required to follow standards and requirements laid down by the Department of Education to assess the annual performance of their schools. The policy has been controversial, and debates have focused on its effectiveness in improving student performance as well as other unintended outcomes— for example, grade inflation, teaching-to-the-test, or gaming the system, which might result when the system responds to specific objective measures. Working with the CPS, Jacob and Levitt (2004) presented an investigation of the prevalence of cheating by school personnel in the annual ITBS. The sample included all students in Grades 3 to 7 for the years from 1993 to 2000. By identifying “unusually large increases followed by small gains or even declines in test scores the next year and unexpected patterns in students’ answers” (p. 72) as indicators of cheating and a retesting experiment in 2002, the authors concluded that cheating on standardized tests occurs in about 4% to 5% of elementary school classrooms. The frequency of cheating was also found to increase following the introduction of high-stakes testing, especially in the low-performing classrooms. The investigation showed that cheating is not likely to be a serious problem in high-stakes testing but confirmed that unintended behavioral responses would be induced under a different incentive structure. This creates a challenge for policy makers to design incentive structures that could minimize the disruptive behavior. In this section, an overview of the NCLB legislation and empirical evidence on student performance impact from stronger accountability measures in Florida and Chicago are discussed.

The No Child Left Behind Legislation

Immediately after President George W. Bush took office in 2001, he proposed the legislation of NCLB, aiming to improve the performance of U.S. elementary and secondary schools. The act requires all states to test public school students in Grades 3 through 8 annually and in Grades 10 to 12 at least once, subject to parameters set by the U.S. Department of Education. The states set their own proficiency standards, known as adequate yearly progress (AYP), as well as a schedule of target levels for the percentage of proficient students at the school level. Such performance-based assessment reinforces the accountability movements that were adopted in many states prior to NCLB (by 2000, 39 states had some sort of accountability system at the school level). If a school persistently fails to meet performance expectations, it will face increasing sanctions that include providing eligible students with the option of moving to a better public school or the opportunity to receive free tutoring, which the act refers to as supplemental educational services. States and school districts also have more flexibility in the use of federal education funds to allocate resources for their particular needs, such as hiring new teachers or improving teacher training.

Florida’s A+ Plan for Education

Florida’s A+ Plan for Education, initiated in 1999, implemented annual curriculum-based testing of all students in Grades 3 through 10. The Stanford-9 Achievement Test (SAT-9) was instituted as the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT) in 2000. All public and charter schools receive annual grades from A to F based on aggregate test performance, and rewards are given to high-performing schools, while sanctions as well as additional assistance are given to low-performing schools. The most controversial component of the plan is the opportunity scholarships, which are offered to students attending schools that received an F grade for 2 years during a 4-year period. In 2006, the Florida Supreme Court issued a ruling declaring the private school option of the Opportunity Scholarship Program unconstitutional, and students are no longer offered the opportunity to transfer to a private school; however, the option to attend a higher-performing public school remains in effect.

Prior to the A+ Plan, in 1996 Florida had begun rating schools based on their aggregate test performance (based on a nationally norm-referenced test such as the ITBS or SAT-8) on students in Grades 3 through 10 in reading and mathematics. Based on student performance, schools were stratified into four categories on the Critically Low Performing Schools List, and schools receiving the lowest classification were likely to receive a stigma effect because of the grading.

David Figlio and Rouse (2006) examined the Florida student-level data from a subset of school districts from 1995 to 2000 to assess the effects of both the voucher threat and the grade stigma on public school performance. The analysis showed positive effects on student outcomes in mathematics in low-performing schools, but the primary improvements were concentrated in the high-stakes grades (prior to 2001 to 2002, students in Grades 4, 8, and 10 were tested in reading and writing, and students in Grades 5, 8, and 10 were tested in math). Their results also found that schools concentrated more effort on low-performing students in the sample.

Chicago Public Schools

In 1996, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) introduced a school accountability system in which elementary schools were put on probation if the proficiency counts (i.e., the number of students who achieved a given level of proficiency) in reading on the ITBS were lower than the national norm. Schools on probation were required to implement improvement plans and would face sanctions and public reports if their students’ scores did not improve.

After the introduction of NCLB in 2002, CPS designated the use of proficiency counts based on the Illinois Standards Achievement Test (ISAT), which had been introduced by the Illinois State Board of Education in 1998 to 1999 as the statewide assessment, as the key measure of school performance. Subject to the requirement of the act, the ISAT test in 2002 changed from a relatively low-stakes state assessment to a high-stakes exam under the national assessment.

Derek Neal and Diane Schanzenbach (in press) examined data from CPS to assess the impact of the introduction of these two separate accountability systems. The analysis compared students who took a specific high-stake exam under a new accountability system with students who took the same exam under low stakes in the year before the accountability system was implemented. The results show that students in the middle of the distribution scored significantly higher than expected. In contrast, students in the bottom of the distribution did not score higher following the introduction of accountability, and only mixed results could be found among the most advantaged students.

Both the Florida and the Chicago results show performance effects on public school performance after the introduction of stronger accountability measures. However, given that the effects are not uniformly distributed across students with different abilities and are often concentrated in students of high-stakes grades, both studies raise concerns about resource allocation when responding to such accountability measures and call for more research on policy design that can minimize disrupted incentives.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The economics of education is a growing and exciting field in economic research. As reviewed in this research paper, the empirical analysis in the field has already provided many insightful ideas for current education issues that are relevant to public policy. The new research in the area has started to adopt a more structural approach to understand the impact of education reform policies that have often induced responses from different players— for example, using general equilibrium analysis to model the linkage between housing decisions and school consumption to measure the potential benefits on school quality with school choice policy (see Bayer, Fernando, & McMillan, 2007; Nechyba, 2000). These new papers use innovative measurement design and more detailed microlevel data and can complement the findings from reduced-form analysis in the literature as well as identify the channels through which the policy effect is being brought about.

See also:

Bibliography:

- Arrow, K. (1973). Higher education as a filter. Journal of Public Economics, 2(3), 193-216.

- Ashenfelter, O., & Rouse, C. (1998). Income, schooling, and ability: Evidence from a new sample of identical twins. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(1), 253-284.

- Bayer, P., & Fernando, F., & McMillan, R. (2007). A unified framework for measuring preferences for schools and neighborhoods. Journal of Political Economy, 115, 588-638.

- Bayer, P., & McMillan, R. (2005). Choice and competition in local education markets (Working Paper No. 11802). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Becker, G. (1964). Human capital. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Belfield, C. (2000). Economic principles for education. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Benjamin, D., Gunderson, M., Limieux, T., & Riddell, C. (2007). Labour market economics: Theory, evidence, and policy in Canada (6th ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

- Card, D., & Krueger, A. (1996). School resources and student outcomes: An overview of the literature and new evidence from North and South Carolina. Journal of Economic Perspective, 10(4), 31-50.

- Chan, P. (2009). School choice, competition, and public school performance. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Checchi, D. (2006). The economics of education. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohn, E., & Geske, G. (1990). The economics of education (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

- Coleman, J. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Coleman, J., Hoffer, T., & Kilgore, S. (1982). High school achievement: Public, Catholic and private schools compared. New York: Basic Books.

- Cullen, J., Jacob, B., & Levitt, S. (2005). The impact of school choice on student outcomes: An analysis of the Chicago Public Schools. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 729-760.

- Dahl, G., & Lochner, L. (2008). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the earned income tax (Working Paper No. 14599). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Figlio, D., & Rouse, C. (2006). Do accountability and voucher threats improve low-performing schools? Journal of Public Economics, 90, 239-255.

- Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Glass, G., & Smith, M. (1979). Meta-analysis of research on class size and achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 1(1), 2-16.

- Grogger, J., & Neal, D. (2000). Further evidence on the effects of Catholic secondary schooling. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 1, 151-193.

- Hanushek, E. (1986). The economics of schooling. Journal of Economic Literature, 24, 1141-1177.

- Hanushek, E. (2006). School resources. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 2, pp. 865-908). New York: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Hanushek, E., & Kain, J. (1972). On the value of “equality of educational opportunity” as a guide to public policy. In F. Mosteller & D. P. Moynihan (Eds.), On equality of educational opportunity (pp. 116-145). New York: Random House.

- Hanushek, E., & Welch, F. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of the economics of education (Vols. 1 & 2). New York: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Heckman,J., Lochner, L., & Todd, P. (2006). Earnings functions, rates of return and treatment effects: The Mincer equation and beyond. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 307-458). NewYork: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Hoxby, C. (2000). The effect of class size on student achievement: New evidence from population variation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1239-1285.

- Krueger, A. (1999). Experimental estimates of education production functions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 497-532.

- Jacob, B., & Levitt, S. (2004, winter). To catch a cheat. Education Next, 4(1), 69-75.

- Lang, K., & Kropp, D. (1986). Human capital versus sorting: The effects of compulsory attendance laws. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101(2), 609-624.

- Lazear, E. (2001). Educational production. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(3), 777-803.

- Levin, H. (1989). Mapping the economics of education: An introductory essay. Educational Researcher, 18(4), 13-16, 73.

- Manski, C. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. Review of Economic Studies, 60, 531-542.

- Mayer, S. (1997). What money can’t buy: Family income and children’s life Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- McMillan, R. (2005). Competition, incentives, and public school production. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 1131-1154.

- Milligan, K., & Stabile, M. (2009). Do child benefits affect the wellbeing of children? Evidence from Canadian child benefit expansions (Working Paper No. 12). Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Canadian Labour Market and Skills Researcher Network.

- Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, experience, and earnings. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Neal, D., & Schanzenbach, D. (in press). Left behind by design: Proficiency counts and test-based accountability. Review of Economics and Statistics.

- Nechyba, T. (2000). Mobility, targeting, and private school vouchers. American Economic Review, 90(1), 130-146.

- Rouse, C. (1998). Private school vouchers and student achievement: An evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(2), 553-602.

- Schultz, T. (1963). The economic value of education. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.