This sample The European Economic and Monetary Union Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the economics research paper topics.

In this research paper we address the issues relating to the past, present, and future of the European Monetary Union (EMU), focusing on the way in which the main socioeconomic sectors within the most important European Union (EU) member states have used the process of European monetary integration to enhance their competitive position not only in the European arena but also in the global context.

This research paper will study in a historical perspective the phases leading to the establishment of the currency union, the present working of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), and the future of the EMU.

What Is the European Economic and Monetary Union?

EMU shall be read as a major institutional undertaking whose economic outcomes are not only constrained but also defined by its institutional framework. This is to say that the economic consequences of EMU are specific to the way in which this particular currency union has been devised, and this, in turn, is the product of a unique historical process.

Although the member states of the EU had been debating about creating an area of exchange rate stability in Europe since the end of the 1960s, its effective implementation took place only 30 years later.

Scholars identify four stages in the development of the process of European monetary integration.

The first stage goes from the Treaty of Rome (1957) to the Werner Report (1970). During this phase, the debate over the establishment of a single currency in Europe was almost nonexistent thanks to the international currency stability guaranteed by the Bretton Woods agreement from the immediate postwar period. However, the difficulty for the U.S. dollar to keep its value vis-à-vis gold as required by the Bretton Wood system, especially between 1968 and 1969, threatened the common price system of the common agricultural policy, a main pillar of what was then the European Economic Community (EEC). In response to this enhanced international monetary instability, the EEC’s heads of state and government set up a high-level group led by Pierre Werner, the Luxembourg prime minister at the time, to report on how the EMU could be achieved by 1980.

The second phase spans from the Werner Report to the establishment of the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1979. This phase was characterized by the attempt to implement the Werner plan. This provided for a three-stage process to achieve the EMU within 10 years and included the possibility of introducing a single currency. The first stage in the implementation of the Werner plan was represented by reducing the level of instability of the European exchange rates. An attempt was made to achieve this aim through the establishment of the so-called Snake, an exchange rate arrangement based on fixing bilaterally the exchange rates among the European currencies. However, the international economic instability, especially the oil crises of the 1970s, made similar futile attempts, and the Werner plan was abandoned.

The third stage in the development of the process of European monetary integration started with the launch of the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) of the EMS in 1979 and ended with the issue of the Delors plan in 1989. The EMS was based on three elements. The first was the ERM, which provided for the pegging of the exchange rates of the currencies participating in it within predefined fluctuation bands (ranging from ±2.25% to ±6%). The second element was the introduction of the European Currency Unit (ECU), a virtual, basket currency made up of a certain amount of each currency participating in the EMS. The last element was the very short-term lending facilities (VSTLFs) guaranteeing the possibility for all the central banks participating in ERM to intervene in the currency markets when necessary. The EMS succeeded in keeping the level of the exchange rate stable and in allowing for the introduction of anti-inflationary policies in most of the EU member states. It therefore represented the starting point for the discussion leading to the implementation of a full monetary union in Europe (EMU).

At the request of the European leaders, in 1989, European Commission President Jacques Delors and the central bank governors of the EU member states produced the Delors Report on how to achieve a currency union by the end of the 1990s. This represented the beginning of the fourth phase in the process of European monetary integration, which ended with the introduction of the euro in 1999.

The Delors Report reproposed the approach of the Werner plan based on a three-stage preparatory period. The three stages were as follows:

- 1990-1994: completion of the internal market, especially full liberalization of capital movements

- 1994-1999: establishment of the European Monetary Institute, preparation for the ECB and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), and achievement of economic convergence through the convergence criteria (see below)

- 1999 onward: the beginning of the ECB, the fixing of exchange rates, and the introduction of the euro

The European leaders accepted the recommendations of the Delors Report. The new Treaty on European Union, which contained the provisions needed to implement the EMU, was agreed at the European Council held at Maastricht, the Netherlands, in December 1991.

On January 1, 1999, the euro was introduced alongside national currencies. Euro coins and banknotes were launched on January 1, 2002.

From an institutional point of view, the EMU was defined by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty (Treaty on European Union) and its protocols. The treaty specifies the objectives of the EMU, who is responsible for what, and what conditions member states were required to satisfy to be able to enter the euro area. These conditions are known as the “convergence criteria” (or “Maastricht criteria”). They include permanence in the “new” ERM (±15% bands) for at least 2 years; inflation rates no more than 1.5% higher than the average of the three member states with the lowest inflation rate; interest rates no more than 2% higher than the average of the three member states with the lowest interest rates; a debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio not exceeding 60%, subject to conditions; and, most important, a deficit to GDP ratio not exceeding 3% (TEU art. 104(c) and art. 109 (j)).

With the introduction of the euro, the independent ECB, created only for this purpose, became responsible for the monetary policy of the whole euro area. The ECB and the national central banks of the member states compose the Eurosystem.

The Governing Council of the ECB, which comprises the governors of the national central banks of the euro area member states and the members of the ECB’s Executive Board, is the only body that has the capacity to make monetary policy decisions in the euro area. These decisions theoretically are taken totally independently from the influence of the national member states’ governments, parliaments, or central banks and from any other EU institution.

The treaty defined the only goal of the ECB, which is to ensure price stability within the euro area. According to the statute of the ECB, price inflation in the euro area must be kept below but close to 2% over the medium term.

National governments retain full responsibility for their own structural policies (notably, labor, pension, and capital markets) but agree to their coordination with the aim of achieving the common goals of stability, growth, and employment.

Also, fiscal policy (tax and spending) remains in the hands of individual national governments. However, they have agreed on a common approach to public finances enshrined in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

The economic viability and the political (or political economy) rationale of the Maastricht criteria have been the subject of a number of studies from the most various academic points of view, which is why the issue will not be tackled here. What is important to underline is, however, that their strict anti-inflationary aim was even strengthened by the adoption of the SGP (Talani & Casey, 2008). The first version of the pact confirmed the objective of a deficit to GDP ratio not exceeding 3% and commits EMU member states to a medium-term budgetary stance close to balance or in surplus (Talani & Casey, 2008). It also defined the terms and sanctions of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP; Gros & Thygesen, 1998, p. 341).

What are the macroeconomic consequences of this institutional setting? How did the EMU affect the real economy of the member states? Did the EMU lead to more or less unemployment? The next section will try to answer these questions.

The EMU and Unemployment

There are two ways of verifying whether the EMU increased or decreased the level of unemployment in the euro area. The first way is to assess to what extent this particular form of currency union contains a recessive bias, thus reducing the level of output, ceteris paribus. The other way is to see how the establishment of the EMU has been linked in theory and in practice to the flexibility of labor markets. These two streams of reasoning might have opposite outcomes. Indeed, while the former would point to an increase in the level of unemployment, the second could lead to its decrease. However, the tricky aspect lies in the fact that the first way of reasoning might be used to further the second, thus adding to its economic rationale and fostering its political feasibility.

The first stream of economic reasoning assesses the overall recessive effects of the implementation of the Maastricht fiscal criteria and/or of the SGP. Some authors have argued that the effort brought about by the implementation of the Maastricht criteria, particularly the fiscal ones, as well as the determination to stick to the ERM in a period of high interest rate policy can explain the upsurge of European unemployment in the 1990s (Artis, 1998). Of course, economic analyses are far from reaching an agreement on the issue. Indeed, the counterarguments tend to underline the necessity of fiscal consolidation and anti-inflationary policies. Others point out that the time period over which unemployment has been growing in Europe is too long to be easily explained in macroeconomic terms (Nickell, 1997). However, deflationary policies implicit in the implementation of the Maastricht criteria to the EMU seem to have eventually worsened the level of European unemployment, at least by increasing the equilibrium rate of unemployment (a phenomenon called hysteresis in the literature; Artis, 1998; Cameron, 1997, 1998, 1999).

Moreover, some econometric simulations show that the implementation of the stability pact from 1974 to 1995 in four European countries (notably, Italy, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom) would have limited economic growth by reducing the annual growth rate (Eichengreen & Wyplosz, 1998, p. 93). This would lead to cumulated output losses of around 5% in France and the United Kingdom and 9% in Italy. The economic theory rationale of these results is, of course, that the SGP constraints would limit (and will limit, in the future) the use of automatic stabilizers to counter recessive waves, thus increasing the severity of recessions. This, however, will happen only if member states are not able to achieve a balanced or surplus budgetary position allowing them to use automatic stabilizers during mild recessive periods in the appropriate way without breaching the Maastricht/SGP threshold.

There is the counterargument that the stability and growth pact gives credibility to the ECB anti-inflationary stances, thus reducing the level of interest rates required to maintain the inflation rate below 2% and boosting the economy. Finally, even if the recessive bias of the fiscal criteria and the SGP were proved, this would not necessarily lead to a higher unemployment level (Artis & Winkler, 1997; Buti, Franco, & Ongena, 1997).

However, there is another way in which the Maastricht criteria and the stability pact might affect unemployment, a more indirect way, which is the basis to justify a neo-functionalist automatic spillover leading from the EMU to labor market flexibility. This is related to how member states should react to possibly arising asymmetric shocks. By definition, autonomous monetary policy and exchange rate policies cannot be used to react to idiosyncratic shocks in a currency union. At the same time, common monetary and exchange rate policy should be used with caution because it can have mixed results in case the other members of the EU are experiencing an opposite business cycle situation. Thus, economic theory leaves few options: fiscal policy, labor mobility, and relative price flexibility.

Indeed, a country could react to an asymmetric shock by using national fiscal policy, both as a countercyclical tool, through the action of automatic stabilizers, and in the form of fiscal transfers to solve more long-term economic disparities (as in the case of Italian Mezzogiorno). However, in the special kind of monetary union analyzed in this research paper, the Maastricht criteria and, to an even bigger extent, the requirements of the SGP constrain substantially the ability of member states to resort to national fiscal policy to tackle asymmetric shocks.

Alternatively, some authors suggest that the redistributive and stabilizing functions of fiscal policy be performed at the European level. Proposals include increasing the size of the European budget, pooling national fiscal policies, and establishing a common fiscal body, which would act as a counterbalance to the ECB (Obstfeld & Peri, 1998). The feasibility of similar proposals looks at least dubious in light of the difficulties EU member states encounter in finding some agreement on the much less challenging task of tax harmonization (Overbeek, 2000). Moreover, discussion about fiscal policy inevitably triggers a discussion on the loss of national sovereignty and a related one on political unification, whose outcomes are still far from being unanimous. Overall, there does not seem to be a compelling will of EU member states to reach an agreement on the creation of a common fiscal policy or to find some way to increase the size of the EU budget so as to introduce a stabilization function.

Given the difficulties in using national fiscal policy to tackle asymmetric shocks and the lack of any substantial fiscal power at the European level, economists suggest the option of resorting to labor mobility. The EU does indeed provide an institutional framework in which labor mobility should be enhanced. The treaty’s articles regarding the free movement of workers, the single-market program, and the provisions about migration of course represent this. However, economic analyses show little evidence of mass migration in response to asymmetric shocks in the EU (unlike in some respects the United States; Obstfeld & Peri, 1998). Indeed, few European policy makers, if any, would seriously endorse temporary mass migration as a credible way to react to national economic strains, for obvious political as well as social considerations.

There thus remains only one policy option for national policy makers to tackle the problems arising from asymmetric shocks: increasing the flexibility of labor markets so that “regions or states affected by adverse shocks can recover by cutting wages, reducing relative prices and taking market shares from the others” (Blanchard, 1998, p. 249). In addition, because reform of the labor market is clearly a structural intervention, it also will help eliminate the structural component of unemployment, apart from the cyclical one, if it is still possible to distinguish between the two (Artis, 1998).

Indeed, the employment rhetoric and strategy officially adopted by EU institutions in the past few years show clearly that the EU has chosen to give priority to labor flexibility and structural reforms as the means to tackle the problem of unemployment in Europe (Talani, 2008, chap. 8). However, the implementation of structural reforms is a costly endeavor that produces social unrest and requires the cooperation of domestic constituencies and actors. Is this effort going to disrupt the EMU and put strains on the process of European integration as a whole? What is the future of the EMU? Before turning to these questions, it is worth analyzing the performance of the ECB in terms of its monetary policy making.

The Monetary Policy of the ECB From Its Establishment

Many were the worries concerning the performance of the ECB at the eve of its establishment, given the unprecedented nature of its tasks for being responsible for the implementation of a European common monetary policy and the management of a European common currency during a lack of full political integration. Some of the issues concerned a lack of credibility of the ECB monetary stances, a lack of flexibility, and a need to increase its democratic accountability and ensure its independence from the governments of the member states. At the onset, it is worth noting that the ECB is the most independent of all central banks. Indeed, its independence is guaranteed by its very statute to ensure as its exclusive goal the achievement of monetary stability, defined as a level of inflation below 2%. Independence from political constraints, both national and supranational, created further preoccupation over the democratic deficit of the European institutional setting but allowed central bankers to concentrate theoretically only on monetary variables, leaving aside the performance of the real economic indicators—namely, growth and employment rates.

The reality of the first years of implementation of a single monetary policy in the euro area, however, demonstrates that monetary policy considerations have not been separated from the performance of the real economy.

According to the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR, 2000), from its inception, the ECB displayed more flexibility than expected regarding asymmetries within the euro zone. This result was possible thanks to the adoption of a so-called two-pillar monetary strategy at the expense of transparency. Given the goal of price stability, defined as a harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) between 0% and 2%, the two pillars of monetary policy are, on one hand, a money growth reference target and, on the other hand, a number of unspecified indicators including the exchange rates and asset prices.

The first issue to address is the importance attributed by the ECB to output growth in euro land (and in some member countries in particular) relative to inflation.

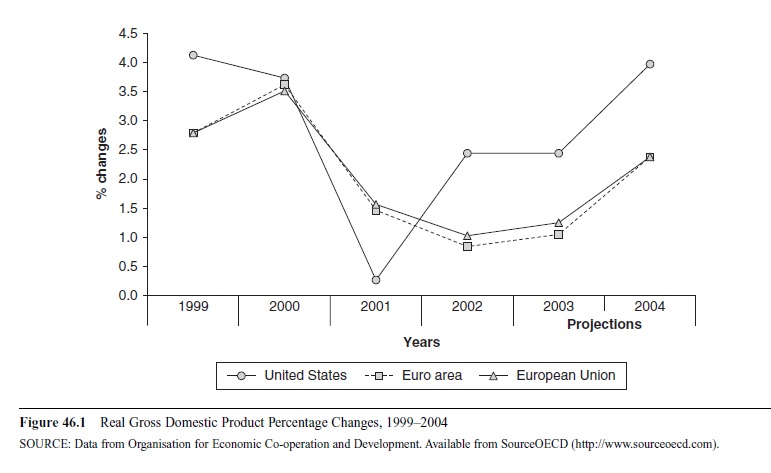

Since the establishment of EMU, in 1999, the economic outlook recorded a marked slowdown in all Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries for the first time since the 1970s. Whereas the Japanese economy had been in a recession for some time already, in 2001, the U.S. economy experienced the first substantial fall of the business cycle in a decade. Also, the euro zone, with a lag of some months with respect to the United States, slowed significantly in 2001 (see Figure 46.1).

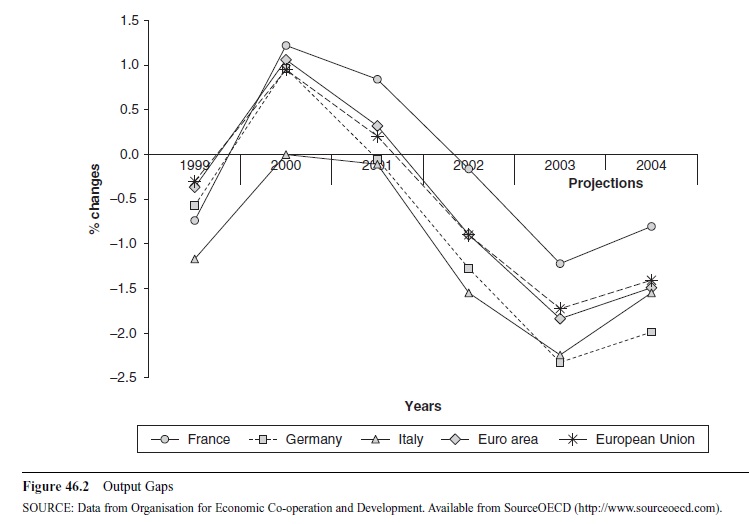

It is important to realize that this had a major impact, especially on the most important European economies— namely, Italy, France, and Germany (see Figure 46.2).

Theoretically, as underlined in many speeches and documents (CEPR, 2002), the ECB would pay little attention to the short-run output developments to avoid the threat of losing credibility in its anti-inflationary stances in front of the financial markets.

Despite this, even with a superficial analysis, it is easy to notice that the 30-point interest rate cut to 3% on January 1, 1999, was associated with deflationary risks in the wake of the Asian crisis. Furthermore, the April 1999 cut to 2.50% coincided with declining output in important euro land members (notably Germany). Finally, the cut on September 17, 2001, in the minimum bid rate on the Eurosystem’s main refinancing operation by 50 points to 3.75, clearly matches a similar decision taken by the U.S. Federal Reserve in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, and their recessive consequences (ECB, Monthly Bulletin, various issues).

More sophisticated analyses clearly show that the ECB monetary policy, particularly the timing and frequency of interest rate changes, reflected the aim to engage in some output stabilization and not only to control prices, although leading central banks personalities constantly denied it (CEPR, 2002).

Figure 46.1 Real Gross Domestic Product Percentage Changes, 1999-2004

Figure 46.1 Real Gross Domestic Product Percentage Changes, 1999-2004

Figure 46.2 Output Gaps

Figure 46.2 Output Gaps

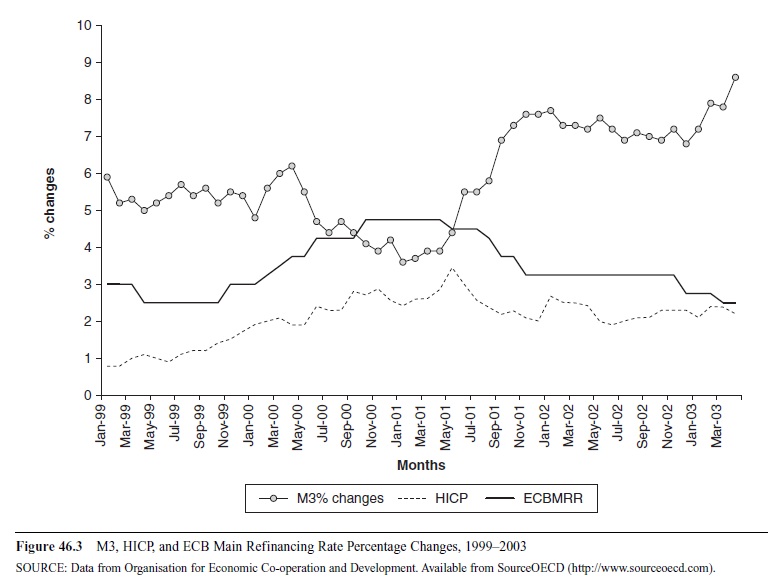

If the output level was never officially recognized as a point of reference in the monetary policy making of the ECB but was certainly taken into consideration, the opposite happened with monetary targets. Indeed, the “two-pillar” strategy theoretically rests on the prominence of the target for M3 (monetary aggregate) growth as the main official indicator for ECB monetary policy decisions. However, on many occasions, when the target was overshot, the ECB did not react accordingly. For example, despite the fact that the target had been publicly set at 4.5% for 1999, no measures were taken by the ECB when it became clear that the target would not be achieved by the end of the year. On the contrary, the ECB cut the interest rates and engaged in sophisticated explanations about why the departure from the reference M3 growth rate did not represent any rupture with the two-pillar monetary strategy.

As the outlook for inflation turned upward by the end of 1999, the ECB did promptly intervene by increasing the interest rate by 50 basis points. Of course, given the parallel increase in the M3 growth, this seemed to be consistent with the monetary strategy declared by the ECB, while the final divorce between the ECB changes in the interest rates and the M3 growth rate appears justified by the necessity to keep the HICP within the 2% limit.

In any case, experts suspected that the M3 target was never really given the importance implicit in the adoption of the two-pillar strategy and was often subordinated to pragmatic considerations about the level of output. Indeed, reacting to the many criticisms toward the first pillar, the ECB effected some modifications of the M3 series by first removing nonresident holdings of money market funds from the definition of euro zone M3 and then purging nonresident holdings of liquid money, market paper, and securities.

However, this adjustment is no more than a cosmetic change and does not improve the reliability of the monetary pillar. If anything, Figure 46.3 shows that M3 percentage changes and interest rate decisions by the ECB, in its first years of activity, went in opposite directions.

Even more obscure is the role attributed by the ECB to the exchange rates within the two-pillar monetary strategy (CEPR, 2000). Indeed, the second pillar of the strategy makes explicit reference to a series of indicators influencing the ECB monetary decisions, among which are the exchange rates of the euro.

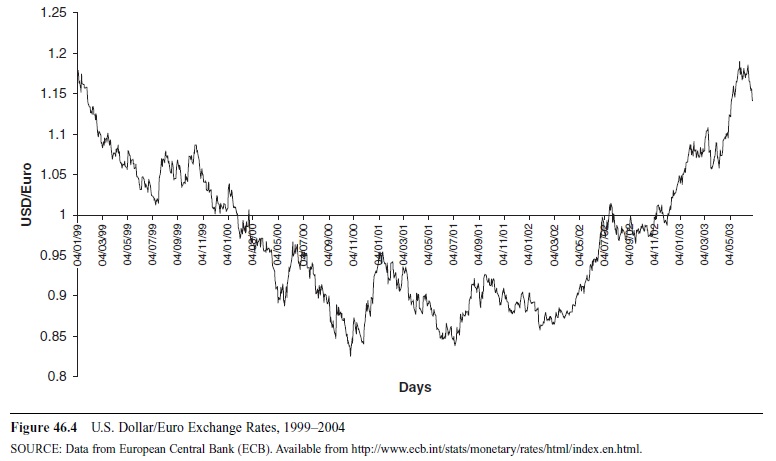

However, looking at the performance of the newly born currency in the first months of its existence raises spontaneously the suspicion that the bank had adopted an attitude of “benign neglect” vis-à-vis the exchange rate of the euro.

Indeed, the euro lost around 15% of its value vis-à-vis the dollar between August 1999 and August 2000, while the parity with the dollar was already lost in January 2000. Also, the effective nominal and real exchange rate of the euro experienced a marked decrease (-11.3 and -10.1, respectively, between August 1999 and August 2000; see Figure 46.4).

Figure 46.3 M3, HICP, and ECB Main Refinancing Rate Percentage Changes, 1999-2003

Figure 46.3 M3, HICP, and ECB Main Refinancing Rate Percentage Changes, 1999-2003

Figure 46.4 U.S. Dollar/Euro Exchange Rates, 1999-2004

Figure 46.4 U.S. Dollar/Euro Exchange Rates, 1999-2004

Of course, the ECB has always underlined that the performance of a currency must be assessed in the long run. And indeed, in the long run, the euro/dollar exchange rate has witnessed a reversal of its previous performance, with a marked appreciation of the euro, although it might be better to talk about a strong depreciation of the dollar.

However, the substantial lack of concern about the fall of the euro on the side of the European monetary authorities provoked further doubts about the real scope of the two-pillar strategy.

In a few words, the emphasis on the performance of the monetary aggregates (M3) as the first pillar of the ECB monetary strategy seems to conceal the desire by the central bank to trade off some of the transparency that the adoption of an alternative monetary strategy would imply (like targeting the inflation rate, for example), in exchange for more flexibility. In turn, this flexibility has been used to pursue output objectives that would not be acceptable otherwise within the strict anti-inflationary mandate of the ECB (CEPR, 2002).

Similarly, the attitude of the ECB toward the performance of the exchange rate—particularly in the first two years of its activity, an attitude that the economists fail to fully understand (Artis, 2003)—acquires a completely different meaning in light of analyzing the manufacturing export performance of the euro zone, particularly some of the euro zone countries (Talani, 2005). The export-oriented manufacturing sectors gained the most from a devalued currency.

Focusing on changes in the balance of trade in goods with the United States between 1995 and 2001, the data indicate that the countries recording the highest improvements of their trade balances with the United States were Italy (from 0.7% to 1.2%), France (from -0.3% to 0.55%) and Germany (from 0.6% to 1.5%) (Talani, 2005).

Therefore, the countries heavily relying on the performance of the export-oriented manufacturing sector, such as Italy, Germany, and France, had a vested interest in adopting a “laissez-faire” policy with respect to the depreciation of the euro.

Things, however, drastically changed when the dollar started depreciating, leaving members of the euro zone with the long-lasting problem of how to increase their economic competitiveness, especially after the globalization of the world economy started biting.

The Future of EMU: Toward the Disruption of the European Monetary Integration Process?

What is the future of the EMU? Is the EMU unsustainable, especially in light of the global economic crisis? Will it lead to the disruption of the whole European integration process? Some answers about the disruptive potential of the EMU on European integration have already been given by the crisis and reform of the stability and growth pact.

Refrigerated, hospitalized, dead: These were the adjectives the press used to describe the SGP on the eve of the historic Council of Ministers for Economic and Financial Affairs (ECOFIN) decision not to impose sanctions on the delinquent French and German fiscal stances. The fate of the SGP was settled in the early hours on November 25, 2003, in what was a true institutional crisis between the European Commission and the ECB on one side, demanding that the rules be applied, and the intergovernmentalist ensemble of the euro zone finance ministers rejecting the application of sanctions to the leading EU member states.

The most amazing thing was that, throughout the crisis, the euro remained stronger than ever and that the markets did not even think about speculating on the lack of credibility of a post-SGP EMU (Talani & Casey, 2008). Here a fundamental paradox arises: How can a currency remain as strong as ever in the midst of a serious crisis of the fiscal rule? The answer shall be sought in the interests of the socioeconomic sectors of the most important EU member states—namely, Germany and France. Here lies also the answer to the future of the EMU.

In other words, the economic interests of the French and German business sectors aimed at increasing their competitiveness, after relying briefly on the devaluation of the euro, with the reversal of this trend, focused on a reduction of taxes and on the implementation of the structural reforms (Crouch, 2002). In turn, the adoption of structural reform had still to rely on the consensus of the trade unions. This means that when the external, international conditions could not be modified by their previous institutional referents, such as the ECB, socioeconomic groups and the governments supporting their interests modified their policy preferences and decided to target other referents—in this case, ECOFIN. On the basis of similar considerations, it is possible to explain why, from 2002 onward, given the unlikelihood that the ECB could reverse or even slow down the depreciation of the dollar, the most powerful member states—namely, Germany and France—sought to obtain a relaxation of the macroeconomic policy framework, much needed by their economic domestic actors, by loosening the grip of the SGP. The exact timing of the crisis, in turn, was defined by the political needs of Germany involved precisely in November/December 2003 in the final stages of a tough negotiation with both the opposition and the trade unions for the approval of a package of structural reform denominated Agenda 2010 (Talani & Casey, 2008).

As underlined above, however, the demise of the SGP did not signify an abandonment of the EMU project but only a short-term contingent shift of the economic interests of the most powerful euro zone states. Therefore, the credibility of their commitment to the EMU remained intact, and the markets did not feel the need to attack the euro in the aftermath of abandoning the fiscal rule or to bet against the stability of the EMU by asking for higher yields. In brief, the future of the EMU was safe, the credibility of the EMU project was still rooted in structural considerations, and the decision to relax the fiscal rule was justified by a change of macroeconomic preferences by the leading socioeconomic groups in their quest for competitiveness. Concluding on a more general note, it is very likely that, despite the general economic crisis, the EMU will survive until it meets the economic interests of Germany and France.

See also:

Bibliography:

- Artis, M. (1998). The unemployment problem. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 14(3), 98-109.

- Artis, M. (2003). EMU: Four years on. Florence, Italy: European University Institute.

- Artis, M., & Winkler, B. (1997). The stability pact: Safeguarding the credibility of the European Central Bank (CEPR Discussion Paper No. 1688). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Blanchard, O. J. (1998). Discussion to “Regional non-adjustment and fiscal policy.” Economic Policy, 26, 249.

- Buti, M., Franco, D., & Ongena, H. (1997). Budgetary policies during recessions: Retrospective application of the stability and growth pact to the post-war period (Economic Paper No. 121). Brussels: European Commission.

- Cameron, D. (1997). Economic and monetary union: Underlying imperatives and third-stage dilemmas. Journal of European Public Policy, 4, 455-485.

- Cameron, D. (1998). EMU after 1999: The implications and dilemmas of the third stage. Columbia Journal of European Law, 4, 425-446.

- Cameron, D. (1999). Unemployment in the new Europe: The contours of the problem (RSC No. 99/35). Florence, Italy: European University Institute.

- Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). (2000). One money, many countries: Monitoring the European Central Bank 2. London: Author.

- Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). (2002). Surviving the slow-down: Monitoring the EUROPEAN Central Bank 4. London: Author.

- Crouch, C. (2002). The euro, and labour markets and wage policies. In K. Dyson (Ed.), European states and the euro. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Eichengreen, B., & Wyplosz, C. (1998). The stability pact: More than a minor nuisance? Economic Policy, 26, 65-114.

- Gros, D., & Thygesen, N. (1998). European monetary integration. London: Longman.

- Nickell, S. (1997). Unemployment and labour market rigidities: Europe vs North America. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11, 55-74.

- Obstfeld, M., & Peri, G. (1998). Regional non-adjustment and fiscal policy. Economic Policy, 26, 205-247.

- Overbeek, H. (Ed.). (2003). The political economy of European unemployment. London: Routledge.

- Talani, L. S. (2005). The European Central Bank: Between growth and stability. Comparative European Politics, 3, 204-231.

- Talani, L. S. (2008). The Maastricht way to the European employment strategy. In S. Baroncelli, C. Spagnolo, & L. S. Talani (Eds.), Back to Maastricht: Obstacles to constitutional reform within the EU Treaty (1991-2007). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Talani, L. S., & Casey, B. (2008). Between growth and stability: The demise and reform ofthe stability and growth pact. London: Edward Elgar.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.