This sample Lifelong Education in Bioethics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

This research paper provides a brief account of the history of education in bioethics, with particular emphasis on the development in the USA, since it was at institutions in the USA that such education was first implemented. This is followed by a presentation of the steps that led to the concept of lifelong learning and the global action in the field of lifelong learning from different approaches. One of these approaches, i.e., the methodology/model of problematization, is presented in more detail, including a brief account of two pedagogical approaches from which this model has taken its inspiration; on the one hand, the Socratic method of maieutics and on the other hand, the proposal of Paulo Freire labeled popular education. The model of problematization is presented through its objectives, the importance of contents, the different steps of the education process, and finally the main differences compared to other proposals such as problem-based learning. Finally, some of the achievements of the Lifelong Education Programme in Bioethics developed in Latin America and the Caribbean by the bioethics network (Redbioetica) supported by UNESCO is presented. This is a distance learning program applying the problematization model and the human rights approach.

Introduction

Lifelong learning has become an indispensable approach to analyzing any educational program for both university students and adults in general. It is no longer just a mere educational methodology but an approach that embraces a conception of the individual as rational and critical and of the society as democratic, inclusive, tolerant, and participatory. This means that individuals participating in the process of learning through such an approach are active participants in the transformation processes, i.e., citizens who participate actively in the social changes through a process of reflection and action. Ethics education is an essential part of this process, both formally and as so far as it promotes a critical reflection on the values defended and promoted by the subjects themselves. The teaching of bioethics cannot be oblivious to this even though for many years it was not influenced by the educational trends that in recent years have impacted and transformed the educational forms globally. The text therefore refers not only to lifelong education but also to the ways in which this approach can be a valuable tool for education in bioethics, through a broad view called the approach of problematization, which includes the vision of a global bioethics as well as the social and environmental issues that are at the basis of an ethics of life.

Lifelong Learning/Education Throughout Life In Bioethics (LLB): Background

Despite its long history, lifelong learning (LL) has begun to be applied in the field of bioethics education only recently, when bioethics broadened its goals and began to become integrated with other educational strategies in medical schools. In order to understand how and when the proposal arrived to bioethics, we need first to explore the history of LL or education throughout life.

The paradigm of lifelong learning has become enormously relevant in the twentieth century, within the frame of a great diversity of approaches and objectives, “from radical-egalitarian to conservatory and confirming the existing order” (Kallen 1996, p. 16). Many scholars agree that the emergence of the concept of education throughout life (ETL) is the result of sociocultural and economic situations in the late nineteenth century in Europe. Industrialization underscored the need for adult literacy of a new working class that was beginning to unionize and step up its demands, through an emancipating liberal model that became integrated with the leftist political parties. Initially, these early demands were more related to the social and cultural needs of an emerging social class than to the interests of the industrial class or the formal education system (Kallen 1996, p. 17). By the early twentieth century, other factors were already at play: the process of industrialization and the new large living compounds built for the workers and, later, the economic crisis that followed World War I and the return home of the soldiers who rejoined the formal education system. Industrial development also required training in specific abilities and skills to handle the new technologies.

The concept of LL was formally introduced in the UK in the early twentieth century, and in fact the term was first used in 1919, but it was not until the post-World War II period, with its need for an economic, but also political, moral, and cultural, reconstruction of society, that the concept of lifelong learning simply meaning adult education developed into a more complex notion involving adaptation to change, flexibility, and tolerance and the promotion of a democratic and humanist education. The 1940s witnessed the emergence of a world movement in which UNESCO had a leading role, organizing the First International Conference on Adult Education in Elsinore, Denmark (1949). This meeting showed that education systems were not responding to the changes taking place in the world and that LL still referred only to adult literacy. In the 1960 (Montreal) and 1972 (Tokyo) conferences, adult education was already regarded as a factor of democratization of society, as an economic, social, and cultural development factor and as an element of integrated education systems. Most importantly, a concept of adult education “for all” was outlined (Vera 2010).

After the 1960s, the theoretical basis and objectives of LL were redefined and it found its way into public policies. Not only UNESCO but the Council of Europe (CoE) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also began to address this issue from very different points of view. Both organizations developed initiatives with objectives and methodologies that were similar in some aspects and very different in others. The CoE structured its education proposal upon three guiding principles or cornerstones for a new policy: equality, participation, and globalization. These initiatives and the studies published in the 1970s were based on the evidence that early education was proving unable to address the increasingly diverse needs of individuals in their own environments. Its publications in the 1970s reflected these proposals, and years later they were included in the so-called 1993 White Paper of the European Union: “Growth, Competitiveness, Employment: The Challenges and Ways Forward into the 21st Century” (European Communities 1993) and the 1995

White Paper (European Union 1995). The year 1996 was declared the European year of lifelong learning, and after 2000, the objectives have been oriented toward the knowledge society throughout life.

OECD proposed a somewhat different paradigm, known as “recurrent education,” as a strategy for lifelong learning, focusing on expanding early education throughout life and providing access opportunities. The paradigm proposed a close connection between education and work, with a strong economic connotation (Vera 2010), aligning education to the needs of the labor market rather than to the needs of the individual. In 1966, UNESCO declared lifelong learning a priority, and in the 1972 International Conference on Adult Education, LL was deemed the framework for locating and determining adult education in general as well as the core of the education debate. In some sense, the emergence of LL represented an answer to the crisis of the new capitalism in the developed countries and was related primarily to the scientific and technological expansion and the pace of rapid growth of the knowledge that required a permanent “updating” of knowledge and an adequate structure and methodology to address adult education. These constant changes did not only occur within the field of technology but had an economic, social, political, and cultural impact, thus requiring individuals with greater adaptation skills, tolerance, and flexibility in the face of changes and differences and who were committed to this reality and capable of a thoughtful and critical participation in these processes of transformation.

The 1970s witnessed the emergence of the demand for a profound education reform, resulting from the evidence that early education was little able to achieve its goals, that it was not providing equal opportunities for access to the labor market (in terms of skills and competencies) and that it was an instrument of indoctrination and repression of spontaneity, perpetuating the existing social hierarchies and “train the docile labour force that the employers wanted” (Kallen 1996, p. 20). As will be shown later, it was in this context that several emancipating and liberal approaches were developed in Latin America questioning the political implications of LL for the excluded sectors of society and resulting in the school of thought known as “popular education” (Rodríguez 2009, p. 72). Paulo Freire, its main advocate, was already preparing the ground for this approach in the Pernambuco Preparatory Regional Seminar for the 1958 II National Conference on Adult Education. A few years later, two seminal documents published by UNESCO showed the direction for LL. The first of these reports, Learning to be, written under the direction of Edgar Faure (Faure 1972), laid the foundation for a new perspective on education, calling for an education leaning toward scientific humanism, for creativity (the quest for new values, for reflection, and for action) and for social commitment (political education, the practice of democracy participation), and capable of developing what the authors call the “complete man”: “The physical, intellectual, emotional and ethical integration of the individual into a complete man is a broad definition of the fundamental aim for education” (Faure 1972, p. 10).

Following the changes of the 1980s and the 1990s, the UNESCO International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century published Learning: The Treasure Within (Delors 1996). The report begins by analyzing the disappointments of the second half of the twentieth century, on the one hand, the disillusion related to progress, in the economic and social spheres, i.e., the growth of unemployment and exclusion in the rich countries, the continuing inequalities in development worldwide together with the threats facing its natural environment. The second disenchantment, on the other hand, refers to world peace and the fact that “since 1945 some 20 million people had died in around 150 wars, both before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall” (Delors 1996, p. 14). These disillusions, the report indicates, make manifest the importance of three main commitments of education in the twenty-first century, namely, peace, freedom, and social justice. Four pillars of education were proposed in the report, along with a number of clarifications regarding the objectives of education:

- It requires an overall consideration: “We must be guided by the Utopian aim of steering the world towards greater mutual understanding, a greater sense of responsibility and greater solidarity, through acceptance of our spiritual and cultural differences” (p. 33). The underlying idea is that helping to understand the world and to understand others results in a better understanding of ourselves.

- Education must foster active citizenship, encouraging participation and integration of minority groups and strengthening democracy.

- Education must foster respect for nature and development, particularly focusing on human development and its requirements.

Learning throughout life is based on four pillars: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together, and learning to be.

Learning to know, by combining a sufficiently broad general knowledge with the opportunity to work in depth on a small number of subjects. This also means learning to learn, so as to benefit from the opportunities education provides throughout life.

Learning to do, in order to acquire not only an occupational skill but also, more broadly, the competence to deal with many situations and work in teams. It also means learning to do in the context of young peoples’ various social and work experiences which may be informal, as a result of the local or national context, or formal, involving courses, alternating study and work.

Learning to live together, by developing an understanding of other people and an appreciation of interdependence – carrying out joint projects and learning to manage conflicts – in a spirit of respect for the values of pluralism, mutual understanding, and peace.

Learning to be, so as to exercise greater independence and judgment combined with a stronger sense of personal responsibility for the attainment of common goals. In that connection, education must not disregard any aspect of a person’s potential: memory, reasoning, aesthetic sense, physical capacities, and communication skills.

The report also states that “formal education systems tend to emphasize the acquisition of knowledge to the detriment of other types of learning; but it is vital now to conceive education in a more encompassing fashion” (Delors 1996, p. 37). Although this is an LL approach, focusing on flexibility, diversity, and access in time and space, the very idea of LL must be reconsidered and broadened.

In the last years, many contributions have been made in this direction, which take a critical look to this approach. Those who take this stand disagree with an ontology regarded as colonial (learning to be dominated), advocating instead for an emancipating approach (Dussel 1980). On the other hand, some take the proposal in relation with the two first pillars guiding education only to practical and technical knowledge.

Lifelong Learning And Bioethics Teaching

Lifelong learning includes a variety of educational currents (Davini 1989a, p. 12): the pedagogy of diagnosis, community education, popular education, pedagogy of problematization, participatory education, different contemporary adult education schools, etc.

The problematization model is part of LL, but its origins can be traced back to the Socratic method of maieutics which provides it with its fundamental base (Davini 1989a). In Latin America, this approach has two different roots of relevance for bioethics teaching. One was the adult education programs fostered by Paulo Freire in the adult literacy campaign in Brazil (Freire 2014). This approach regards education as a “tool” to promote critical thinking of individuals, bringing back their cultural values and using them as “problematizing” elements to develop education programs. Learning is not only a factor of attitudinal change; more importantly, it is a factor of change of an individual’s own practices: “Awareness of the world and awareness of the self-grow together and in a direct relationship; one is the inner light of the other, one is engaged with the other. There is a direct correlation between conquering oneself, becoming more oneself, and conquering the world, making the world more human… This pedagogical method.. .aims at giving man the chance to rediscover himself, while reflexively assuming responsibility for the proper process by which he rediscovers, expresses and shapes himself: the awareness method… but nobody becomes aware separated from the rest; consciousness constitutes itself as awareness of the world” (Fiori 2010, p. 18).

The second source of the problematization model was the Pan American Health Organization’s (PAHO) response to the 1977 World Health Organization’s strategy of Health for All 2000. PAHO’s Human Resources Development Program, created in the 1980s, fostered what was called “lifelong learning in healthcare” (LLH), a concept adopted by many authors to develop the theoretical framework of the model to be used in healthcare education. Hence, one of the key elements of the strategy was the line of work addressing the training of the staff that would apply these strategies, in different ways and with different levels of responsibility. The aim was to analyze the issue of healthcare from the standpoint of the individual’s own political, socioeconomic, and cultural reality, including community participation to develop healthcare issues and to design actions to address them. The decision-making process was more democratic, with interdisciplinary teams that would use training as a strategy for transformation. Training had to be permanent and connected with the real issues affecting institutions and communities and had to aim at creating critical consciousness of healthcare workers regarding their own practices and open channels of communication with society. These educational objectives have not been followed up on strategies for healthcare personnel, but they have been included in the LL bioethics (LLB) education approach to be presented later in this research paper.

A Word Of Caution About LL

Using LL as a tool for transformation has showed that there is a hegemonic paradigm that governs every age and society and that the educational proposals are part of it. And it has become evident that the different models of state organization, its different agencies, healthcare institutions, universities, etc., have developed education strategies that usually support the existing hegemonic power structures. These strategies also contain a discourse about the truth, the right, and what is due that is imposed through vertical structures and usually by an authoritarian organization. Likewise, power holders impose education contents and models that legitimize and perpetuate the power structures that support them, a real liberalization of the education market. Education models embody a certain view of the world and then foster a particular attitude toward reality, what comes to thwart the supposed idea of “neutrality” which usually is granted. Clearly, “this view of the world refers to a certain ideological stance and, by its own nature, it holds values that drive action toward a certain historical project” (Almeida Souza et al 1988, p. 35). Education is a process that seeks to develop a certain subject and a certain society as result of its intervention. Most of the recent education system reforms have revealed the influence of power and the market on learning processes.

Martha C. Nussbaum has referred to the “silent crisis” by which the arts and the humanities are eliminated from the curricula, being “seen by policy-makers as useless frills, at a time when nations must cut away all useless things in order to stay competitive in the global market” (Nussbaum 2010, p. 2).

Due to its interdisciplinary, pluralist, and deliberative nature, bioethics shares several goals with LL, but bioethics education at universities took a different path, particularly in the developed countries. As mentioned earlier, bioethics education was determined by the paradigm of biomedical bioethics as it was developed in the USA, and which kept away from a social, environmental, and contextual approach to ethical problems of life and health, as well as issues such as global justice. The objectives, methods, and curricula of university programs were defined by this paradigm.

The model also brought forth several fractures that need to be addressed when developing an education project. First, it broke with the social and historical roots of a bioethics based on human rights. Second, it broke with the Potterian vision of a global bioethics, concerned with the environment, with global justice, and with the future of mankind. Additionally, the model broke the ties between social and environmental determinants and health and well-being, dismissing the importance of the right to health. Finally, the methodology advocated represented a break with a 2,500-year-old tradition in ethics teaching that went back to the maieutic method of the Socratic school. The approach we call “lifelong learning in bioethics” (LLB) seeks to retrieve those roots and traditions.

LLB: The Basic Odel

The process of learning must be fully understood to develop a teaching methodology and to align the actions with the proposed objectives. There are three different learning processes: knowledge, skills, and attitudes. In recent years, the concept of competences has also been introduced, which in a way encompasses the other three.

Many scholars within the LL model, particularly those identifying themselves with the model of problematization, believe that educational interventions can result in character and attitudinal changes. They also argue that maieutic education can be the best antidote against two temptations: first, the urge to indoctrinate, manipulate, or impose and, second, the tendency to reduce training and education to mere information and receiving instruction. This is a key issue because, in contrast with other approaches, in this case establishing the objectives of (bioethics) education is more important than focusing on contents. Objectives help to define contents and methods. In this regards is important to reviewing the different learning objectives suggested by the EU, the OECD, and the UNESCO in the documents mentioned earlier.

Three corresponding pedagogical models can be derived from the learning processes (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) mentioned above (Davini 1989a). Each model bears a particular hypothesis and assumptions, producing manifest and latent effects and advancing different strategies for practical action and work styles.

Pedagogy of transmission: It entails the uncritical transmission of allegedly neutral knowledge by a teacher, a figure of authority who is entitled to teach to a passive student. Freire has correctly referred to this as the “banking approach” (Freire 2014, pp. 72–96).

Pedagogy of training: It is rooted in behaviorist theories in psychology. Here the teacher is the guide, mechanically teaching techniques or practices. Intellectual development that could enable the individual to understand his practices, reflect on the reasons for action, connect them with one another, and analyze results and consequences, as well as performing value analysis about these consequences and the contexts where these practices are implemented, is not stimulated.

Pedagogy of problematization: This model regards educational action in two different ways (Davini 1989a): either the student possesses everything “within himself” but is unaware of this and will discover it through a maieutic situation or he does not have the knowledge, but through reflection, elaboration, and inquiry, he is able to discover which knowledge he needs. There is no transmission of knowledge here but “an exchange of experiences among individuals, involving both their conscious level of knowledge and their emotions and deep psychology” (Davini 1989a, p. 14). The process aims at enriching knowledge and, at the same time, modifying attitudes. This approach has been regarded as heir to the Socratic maieutic method, later recreated by Freire. The starting point is always a question, an inquiry into the individual’s own reality, experiences, and practices, in the context of his or her social, institutional, and personal situations, whence problems are built.

The concept of problem cannot be developed in these pages but suffices it to say that it refers to “a gap between a reality or one aspect of reality as it is seen, and a value or a wish about how that reality should be in the eyes of a certain individual or collective observer” (Róvere 1993, p. 79). This analysis and this questioning (also called “pedagogy of the question”) should be done with other individuals who share the same problems and realities. It is an instance of collective, collaborative thinking, only feasible when carried out through deliberation and dialogue. Questioning what happens and why it happens helps to broaden the understanding of conflict, particularly when arising from ethical issues, but this can only be achieved through dialogue. Problematizing reality requires adopting a critical stance to it and having in mind the need for a change of practice.

The Socratic model here alluded to has long been criticized (Nussbaum 1997, pp. 35–74) and that criticism is still expressed today, particularly by those who do not accept any questioning of certain beliefs and by those who make an instrumental use of education, adapting it to the needs of certain sectors. Nussbaum argues that criticism of the Socratic model is valuable for our current educational debate: “Seeing young people emerge from modern ‘Think-Academies’ profusely questioning traditional thinking … the most conservative sectors of many kinds have suggested that these universities are homes for the corrupt thinking of a radical elite whose ultimate aim is the subversion of the social fabric” (Nussbaum 1997, pp. 15–16). This is very important in Latin America, where traditional hegemonic thought has strong influence not only over education but also over politics, over religion, and consequently also over the field of bioethics.

The aim of the Socratic model is to challenge conventional wisdom (attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge) to provide reasonable justifications and measure the worth of assertions passing judgment on women, race, social justice, and other values that seem to underlie social order (Nussbaum 1997). With this exercise, individuals are driven to think for themselves and to find the reasons supporting their thoughts and beliefs. This process cannot be done alone but through deliberation with others, through dialogue, and through questioning.

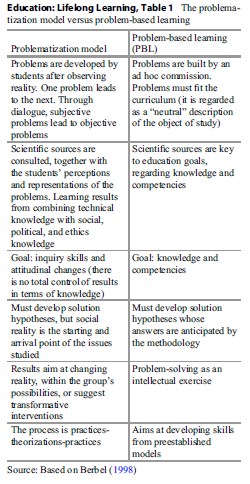

Table 1. The problematization model versus problem-based learning

Table 1. The problematization model versus problem-based learning

In education, this model aims not only at a method of questioning to identify problems but also at problematizing the objectives and contents of the teaching-learning process. When applied to the field of bioethics, this entails starting by asking what the purpose of bioethics education is and how it should be achieved. The model also proposes a procedure for constructing ethical problems from complex situations and for carrying out the deliberative process of bioethics committees and similar groups. The question and answer process can only be accomplished through dialogue and based on rules to ensure respect and tolerance.

Finally, it is necessary to make clear the distinction between LLB through the use of the problematization model and the problem-based learning (PBL) approach (Berbel 1998). The latter has been criticized particularly in connection with the proposal called competency-based learning. As Table 1 shows, there are specific differences between the problematization model and PBL.

Defining Goals In LLB

The point of departure of lifelong learning in bioethics is the idea that individuals are not “blank sheets” ready for printing but the result of their own experiences (assimilation and accommodation patterns), values, practices, culture, and history that constitute their self. Hence, these are elements that must be taken into account in the teaching-learning process, a lifelong process. LLB seeks to develop educational processes resulting in an open moral that foster the individuals’ creative spirit and imagination, their reflexivity and autonomy, their capacity for criticism and change, and their collaborative spirit, broadening their sense of responsibility and solidarity. Bioethics (and ethics) education is embedded in the idea of citizenship building and advancement of democracy thus cannot be conceived outside the social, economic, political, and cultural structure within which it is proposed. The point of departure is a particular individual belonging to his/her social group, age, and place.

This responsibility of educating “citizens of the world” requires as expressed by Nussbaum (1997) certain capacities: “First is the capacity for critical examination of oneself and one’s traditions—for living what, following Socrates, we may call ‘the examined life.’ This means a life that accepts no belief as authority simply because it has been handed down by tradition or become familiar through habit, a life that questions all beliefs and accepts only those that survive reason’s demand for consistency and for justification… Citizens who cultivate their humanity need, further, an ability to see themselves.. .as human beings bound to all other human beings by ties of recognition and concern… The third ability of the citizen closely related to the first two, can be called the narrative imagination. This means the ability to think what it might be like to be in the place of a person different from oneself… and to understand the emotions and wishes and desires that someone so placed might have… But the first step of understanding the world from the point of view of the other is essential to any responsible act of judgment” (Nussbaum 1997, pp. 10–11).

Teaching these capacities has become a matter of great interest among scholars concerned about teaching ethics, particularly to medical students, and seems to be key for adequate moral reasoning.

The problematization approach argues that the idea presented above should be one of the goals of (bio)ethics education, given that many participants in adult learning programs will later become teachers or members of bioethics committees, acting as consultants and advising others for value laden decision-making. This approach rejects the training model in adult education in bioethics, which focuses on merely developing skills to solve specific clinical cases, ignoring the social and environmental contexts where these cases take place, as well as global visions of the ethics of life in general and human health in particular. Case discussion should be embedded in general proposals and should be contextualized, unless we want to drive individuals to the identification of isolated issues, ignoring the reality from which they emerge. Understanding the ethical aspect of a case is only possible by analyzing the cultural and social context of the protagonists and also who is giving advice on the case. We need questioning, and thinking critically from the standpoint of an open moral, putting oneself in the place of the other in order to build a narrative that helps to identify the values involved and the actors representing them. Critical inquiry is the best way to achieve those goals, through questioning and problem building which require, in turn, certain capacities and attitudes that can be developed through education.

Added to the fact that today bioethics can no longer be understood if the social, environmental, and global issues are ignored, bioethics education must include new contents but also new objectives and methodologies to mobilize individuals in new ways.

Stages Of An Education Of Problematization

When applying the problematizing model to design a teaching program, it is important to consider the different moments or stages of the educational process.

The process begins with a diagnosis of the situation: The teacher/facilitator asks questions to stimulate participation and open areas of uncertainty about the topic or situation addressed. This encourages the development of problem areas, distinguishing the emerging problems, separating the subjective elements from the objective ones, and arriving at a prioritization between them. The subjective moment is defined by the student from his individual perspective, and it becomes objective through collaborative reflection and interaction and through contextualizing and construing the problem through dialogue and participation. The diagnosis of the problem can equally be the first stage in the design of an educational program, and it is jointly carried out with those who share similar realities and particularly those who will take part in the teaching-learning process. The question that needs to be answered in this stage is: what are the ethical problems we have (in a healthcare institution, community, a particular context or case)?

The problems should be listed according to a previously defined criterion, and also it is necessary to differentiate the ethical from other types of problems. Once the problems are defined, the next stage is the theoretical and practical moment, consisting of a search of material and sources that may help to broaden and understand the problem, as well as devising possible solutions. This material must be hierarchically organized according to its level of importance and usefulness to conceptualize the problems being addressed. This has been called the theorization of the problem: through questioning, the teacher takes on the role of guide, but the answers are found by the student, through dialogue, interaction and deliberation, searching sources and readings, and identifying ways to solve the problem and applying them to concrete situations. Through theoretical reflection, hypotheses for solution are developed and then checked against the original problem. The final step is the practical proposal to solve the problem by means of an educational action, including a methodological development and the attempt to transform certain practices.

The proposal should also be a recommendation for action or intervention on practices (related to problems or cases).

The Content Of LLB Programs

The next important step is defining the content of educational programs. Content must be determined early on, in connection with the diagnosis of the situation in each concrete reality, gradually including also general introductory content in fundamental bioethics; clinical, social, and global bioethics; and ethics of scientific research, to broaden the field of knowledge and introduce deliberation. It is essential to perform a review of the historic, cultural, social, and environmental roots of the problem in the country or region of origin. Ethical issues, in their complexity, need to be analyzed from different angles, not only from the perspectives of biomedicine and philosophy; the arts, i.e., theater plays, novels, pictures, and music, are excellent sources of awareness raising and stimulation of the narrative imagination.

Undoubtedly, students should be provided with the tools required to access and identify sources and to qualify the material they find. As argued by Davini: “Rather than defining content in an abstract way, in terms of disciplines or profiles, it is important to define which knowledge (theoretical or technological) is necessary to transform practices and attitudes, and their mutual relationships, thus shaping a system of thought and action” (Davini 1989b, pp. 18–29).

The LLB project is clearly connected with two of the pillars of the UNESCO approach to education, learning to live together and learning to be. When these are understood from this methodological approach, they clearly show the way forward for the design of educational programs in bioethics and ethics of science.

Lifelong Education Program In Bioethics (LEPB): A Latin-American Experience

The Lifelong Education Program in Bioethics is an initiative seeking to develop new educational actions in bioethics in Latin America and the Caribbean supported by the UNESCO bioethics network, Redbioetica. Created in 2005, its main goal is to foster critical, plural, and interdisciplinary reflection about the ethical issues arising from human life and health by means of education. LEPB aims at promoting plural and interdisciplinary dialogue about (bio)ethical problems, taking into consideration their complexities, history, and specific aspects of their context of emergence, as well as their universal dimension, social determinants, and the rights of the individuals and communities involved.

Based on a reflection-action model, the program aims at fostering respect for differences and plurality of ideas and moralities, encourages participation and transformative intervention, and considers respect for human rights as a basic requirement for conflict resolution. Three main characteristics of the courses related with the UNESCO perspective are:

– They are based on a human rights approach.

– They take as framework the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UNESCO Bioethics Core Curriculum is part of the material).

– The contents take into account a broad perspective of bioethics including social and environmental issues.

Thus, the main goal of the LEPB is to teach professionals of different disciplines the basic content required to carry out teaching, consulting and normative tasks in bioethics within the framework of a universal conception of justice and human rights, and taking into account the historical, social, and cultural values held of each particular context. The program offers online basic content courses to guide learning with material written by regional experts. But its main feature lies in the debate forums, where tutors ask questions to groups of 30 or 40 students (in each online classroom) from different countries in LAC. The program has a video collection to clarify authors’ positions and a library with additional literature, databases, journals, and internet search engines.

The modality of the LEPB enables many professionals in Latin America and the Caribbean to access courses at a high academic level, advancing Latin-American authors and encouraging the exchange of papers among those who are already working on these issues in different institutions.

Two courses are currently being offered, “Introduction to Research Ethics” and “Introduction to Clinical and Social Bioethics.” The 2015 cohort is the tenth group of students taking these two courses. UNESCO has offered scholarships for LAC professionals, particularly those coming from the less developed, less advantaged countries with fewer resources and who live far from training institutions and whose professions have less access to this kind of education.

Between 2006 and 2014, 1784 students were enrolled in the LEPB. In total, 1249 students from 26 countries in LAC have completed the program.

We have a passing rate of 70 % which is very good for what is expected in distance education. Of the total of 1131, this group received scholarships and 653 paid fees (many of them were paid by educational institutions). From the total of participants, 62 % are women, which reflects a gender priority perspective. Taking into account that in 2015 168 students entered the program (they are in the process to finalize), it means that almost 2000 students have participated in the LEPB between 2006 and 2015, and of whom 70 % have finalized the courses (we don’t have the 2015 results yet).

Graduates are invited to take part in an alumni forum to keep up with the debate and the exchange of ideas. Currently, 1200 professionals are enrolled in this forum, with two thematic classrooms. Students pass courses with a final implementation project, after conducting a diagnosis of the situation and identifying a need for change. In many cases, these projects have generated real practical interventions. They address issues in: education (courses, chairs, training, etc.), institutional development (bioethics committees or commissions), normative function (regulations, institutional guidelines, promotion of rights), or governmental advisory.

An impact assessment of the LEPB program shows three significant results. First, dropout rates have been lower than expected vis-à-vis online training standards, which is a good indicator of the success of the program. Regretfully, most of the dropouts are recipients of scholarships. Second, a survey conducted among alumni about the implementation of their projects, the issues addressed, and, when applicable, the reasons why they have not implemented them shows that a large number of projects have been effectively implemented. Finally, in the students’ evaluation, over 85 % describe the program as very good or excellent.

Scholarship allocation has always been equal for all countries, guaranteeing equal access to countries with fewer possibilities. Regarding the professional background of the students, physicians have since the start been most numerous, although in 2009 their numbers have declined, while more nurses, lawyers, and biochemists are entering the program, as well as professionals from other disciplines, such as veterinary medicine, pedagogy, political sciences, and human resources. Regarding gender, most students are women. The majority of students are over 40 years old and particularly over 50 years old. When students were asked about the program’s level of “accomplishment of educational goals,” 99 % said it was very satisfactory or satisfactory (90 % and 9 %, respectively), and only 1 % said it was poor, which indicates a very high level of satisfaction among participants.

A survey assessing the impact of the interventions developed through the LEPB courses is currently being processed, to assess the real impact of the program and including in-depth interviews to study the success of the program in terms of changes in attitude and professional practice. From all the questionnaires sent (1200), 270 were responded by the former students. 26 % of them had implemented their final project, while 24 % were in the process of implementation. This shows that 50 % of the students have done some action in their institutions which result is a measure of the impact in a different way. 65 % of those projects were educational or development of ethics commissions or committees.

Conclusion

Lifelong learning in bioethics from the problematization methodology aims at helping individuals who take part in the teaching-learning process to acquire a critical reflective attitude about their own practices and those of the societies in which they live. Furthermore, the aim is to enable them to identify ethical issues in life and human health in their societies, develop possible solutions through a dialogue which is pluralist and democratic, and provide justifications legitimizing their recommendations and proposals for concrete actions. In this way, hopefully they can become more responsible not only vis-à-vis themselves and their environment but also become freer, more tolerant, and more prudent. Bioethics teaching not only involves the transmission of knowledge but also the fostering of an attitudinal change among those who will become teachers, members of bioethics committees, and better professionals. Rather than mere training, this requires the joint work of teachers and students through a maieutic form of moral education, which aims at developing critical (self) reflection and the attitudes needed for plural deliberation. This is a process that begins with self-examination followed by thinking about and with others and about other cultures and societies.

Notwithstanding many difficulties, in the last 10 years the LEPB has shown more success than failure. And as mentioned earlier, bioethics education should always aim at contributing to citizenship building and to the promotion of a more just and decent society. The Lifelong Education Program in Bioethics strives to contribute to the achievement of these goals.

Bibliography :

- Almeida Souza, A. M., Galvao, E. A., Dos Santos, I., & Roschke, M. A. (1988). El Proceso Educativo. Educación Permanente del Personal de Salud en la Región de las Américas. Washington, DC: OPS.

- Berbel, N. (1998). A problematização e a aprendizagem baseada em problemas: diferentes termos ou diferentes caminhos? Interface (Botucatu), 2(2), 139–154. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from http://www.scielo. br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-32831998000100008&lng=en&nrm=iso.

- Davini, M. (1989a). Bases Metodológicas para la Educación permanente del personal de Salud. PASCAP 19. PAHO/WHO.

- Davini, M. (1989b). Exploración de la Demanda de Educación Permanente en Salud. Módulo III. Serie Educación Permanente en Salud. PAHO/WHO.

- Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the twenty first century. UNESCO. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/0010/001095/109590eo.pdf.

- Dussel, E. (1980). La pedagógica latinoamericana. Bogotá: Nueva América Editorial.

- European Communities. (1993). Growth, competitiveness, employment. The challenges and ways forward into the 21st century. White Paper. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Bulletin of the European Communities. Supplement 6/93

- European Union. (1995). White Paper on education and training: Teaching and learning. Towards the learning society. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from http:// europa.eu/documents/comm/white_papers/pdf/com95_590_en.pdf.

- Faure, E. (1972). Learning to be: The world of education today and tomorrow. UNESCO. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0000/000018/001801e.pdf.

- Fiori, E. M. (2010). Prólogo. In P. Freire (Ed.), Pedagogía del oprimido. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores.

- Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Kallen, D. (1996). Lifelong-learning in retrospect. European Journal. CEDEFOP. Vocational training Nr. 8/9, 16–22.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1997). Cultivating humanity: A classical defense of reform in liberal education. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2010). Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Rodríguez, L. M. (2009). La educación de adultos en la historia reciente de América Latina y el Caribe. Efora (Vol. 3, pp. 64–82). [Fecha de consulta: dd/mm/aaaa] http://www.usal.es/efora/efora_03/articulos_efora_03/ n3_01_rodriguez.pdf

- Róvere, M. (1993). Planificación Estratégica de Recursos Humanos en Salud. Serie Desarrollo de Recursos Humanos, 96, 79–90.

- Vera, C. S. (2010). “Educación Permanente” y “aprendizaje permanente”: dos modelos teóricoaplicativos diferentes. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 52, 203–23.

- Freire, P. (2014a). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Freire, P. (2014b). Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1997). Cultivating humanity: A classical defense of reform in liberal education.

- Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press. Vidal, S. M. (Ed.). (2012). La Educación en Bioética en América Latina y el Caribe: experiencias realizadas y desafíos futuros. Montevideo: UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org.uy/shs/fileadmin/shs/2012/EducacionBioetic aALC-web.pdf [in Spanish]. Accessed 25 Sept 2015.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.