This sample Health System of the United Kingdom Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Health And Health Care In Britain

Health care is one area in which Britain since 1945 has experienced a quite distinctive arrangement compared with other Western industrialized societies. In 1948 a single health service funded from general taxation was established with aspirations to provide comprehensive and universally available health care. This National Health Service (NHS), which was to be available to all and not based on the ability to pay at the point of delivery, has continued to dominate the British health-care system ever since. By comparison, most European countries have developed similarly extensive health systems but have relied mainly on social insurance as their form of funding, and the United States has largely confined public funding of health care to two groups, the elderly and the poor. This research paper examines the emergence and development of this unique form of health service and considers the many pressures and changes it has faced. Also assessed are trends in the health of British society over this period.

Health Services Prior To The NHS

To understand why a single, publicly funded health service was established after the Second World War it is essential to examine the state of health-care facilities prior to this event. Before the NHS, Britain’s health-care system was a disorganized and complex mixture of private and public services. Following the 1911 National Insurance Act, approximately 40% of the working poor were entitled to free primary health care from a general practitioner (GP), although this scheme did not cover their hospital care or any health-care needs of their families. Two main forms of hospital existed: the voluntary hospital (established by philanthropy or public subscription) and local authority or municipal hospitals (which evolved out of Poor Law hospitals). Both kinds of hospitals typically gave treatment to the poor free of charge, but admission was selective and both struggled to finance adequate services.

By the end of the Second World War several concerns surrounding the state of the nation’s health care emerged. Key among them was that over half the population was not covered by national insurance and had inadequate access to even basic primary care. Major reports commissioned at the time drew attention to the low overall standards of health in Britain, shortages of hospital facilities, and the uneven nature of provision across the country. The high levels of civilian and military casualties resulting from the war further exposed the weaknesses of the system.

The Creation Of A National Health Service

In 1946 a national Health Services Bill was passed, to be followed 2 years later by the establishment of the National Health Service. Negotiations over the form this service should take, between government and interested parties, particularly the medical profession and local government, were difficult and protracted. The issues behind these disputes are important because they explain many of the enduring features and problems of the NHS since its inception. A compromise, required because of disputes between the government and the medical profession, resulted in an NHS that was essentially split into three sectors: hospital medicine (by far the most important in terms of share of expenditure), primary health care (provided by GPs), and local authority health services (such as public health, school, and maternity services). Thus, despite being formally brought together under the Ministry of Health, the NHS began life as a fragmented tripartite system that was poorly integrated, coordinated, and planned. Duplication, overlap, and lack of coordination among the various sectors placed the system under increasing pressure. This, together with an emerging funding crisis in which it became evident that the money made available to the NHS by government was no longer sufficient to meet increasing demands, resulted in a series of organizational and managerial reforms during the 1970s and 1980s.

The Rise Of The Market In Health Care

The continuous need to reduce public spending and to increase organizational efficiency and the promarket orientation of the Conservative government merged at the end of the 1980s and resulted in the most fundamental reform of the NHS since its creation. The package of reforms was first articulated in the 1989 White Paper, Working for Patients, subsequently translated into legislation in the National Health Service and Community Care Act of 1990, and finally implemented in 1991.

Despite suspicion that the proposed reforms were the ‘thin edge of the wedge’ of privatization, the changes that were implemented in 1991 did not alter the financial underpinnings of the NHS. The government preserved free access to health care and kept the tax-based financing, but aimed to use competition among providers of services to improve the efficiency and quality of those services. Essentially this was to be achieved through the creation of an internal market and the separation of health-care purchasing from the provision of services. Producers of hospital and specialist services would now compete with each other for the purchasers of health services, district health authorities, and GP ‘Fundholders’ (GPs who volunteer to manage and control a share of their patients’ budgets). The relationship between providers and purchasers would be formalized through NHS contracts.

With the division of purchasers and providers, and the creation of an internal health market, the NHS embarked on a new trajectory in which established power structures, systems, and values were challenged. Notions of bureaucracy, professionalism, and paternalism became replaced with those of markets, consumerism, and user rights. The previous postwar preoccupation with service coordination and universal care now took second place to concerns about efficiency and choice. Until the late 1980s the NHS had been essentially a ‘command-and-control’ bureaucracy; hospitals were owned and operated by the state, and health-care staff were government employees. GPs, although nominally self-employed, contracted almost exclusively with the state for the provision of their services. The system had many merits. Because doctors were not paid on a fee-for-service basis there was little incentive to overtreat patients. The system was also what economists call ‘macro-efficient,’ absorbing a relatively small proportion of Gross National Product compared with other countries, while providing a service that was not notably inferior in quality or outcome. In other respects, however, the system was less satisfactory because it was generally considered to be ‘micro-inefficient.’ This meant that the combination of clinical freedom and the absence of costing mechanisms led to resources being used in a manner that bore little relationship to their cost-effectiveness and to wide variations in the performance and costs of medical practice. Moreover, the familiar complaint that its monopoly of power made the NHS unresponsive to consumers was shared by those on the policy Left and Right.

The government took the view that centralized controls and the managerialism of the 1980s had been insufficient forces for change, especially at the clinical level. The route to increased cost-effectiveness and quality lay in influencing medical behavior, and this was to be achieved through the introduction of market mechanisms and competition. Once ‘money followed the patient’ providers would have a systematic financial incentive to cut costs, improve quality, and be more responsive to what consumers wanted. Purchasers, in turn, because they would still be cash limited, would have an incentive to bargain for improved value for money on behalf of their patients. It was argued that GP Fundholders were better placed to understand patient needs and preferences than remote health authorities and that they would lead the way in negotiating improvements in services.

1997: The New NHS?

In December 1997 the new Labour government announced its plans for the NHS: the White Paper, The New NHS: Modern, Dependable. It claimed to offer a new model of health care for the UK, one that seeks to replace the internal market with a system of ‘integrated care,’ founded on partnership rather than competition. The model was not a return, however, to the 1970s command and control system, which ‘focused on the needs of organizations rather than the needs of patients.’ Instead, these reforms set out a ‘Third Way’ that keeps the separation between planning and provision, expands the central role of primary care, and keeps decentralized responsibility for operational management.

In practice, it is unclear how much has changed. Although bearing different names, many of the core structures and processes under Labour bear great resemblance to their Conservative predecessors. For example, the purchaser–provider split has remained intact, although the relationships between them were now expected to be longer-term and were called ‘agreements’ rather than ‘contracts.’ Most notably, policy under Labour has continued the shift toward a primary care-led NHS: Although GP Fundholding was abolished in 1997, it was replaced by Primary Care Trusts (PCTs), groups of GP practices covering geographical communities of up to 100 000. These PCTs would be responsible for commissioning and providing hospital, community, and primary care services for their populations, thus taking over responsibilities previously assigned to health authorities and NHS trusts. Thus, the extent to which Labour’s Third Way actually represents a break with the previous model has – and continues to be – greatly debated.

The NHS Today

Funding

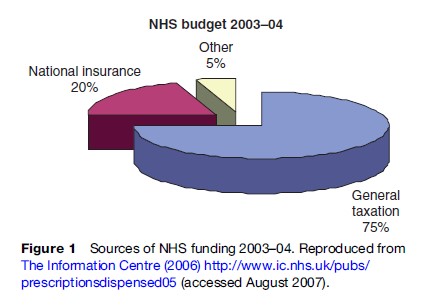

The total NHS health-care budget continues to be determined by Parliament and controlled by the treasury. It is funded predominantly through general taxation and National Insurance contributions, although about 5% comes from miscellaneous sources such as patient user charges (e.g., for prescription medications and dental services) and income from the sale of land and other assets (Figure 1). Because the state plays such a central role in UK health-care funding, and because global resource allocation is largely carried out through administrative decisions rather than market mechanisms, the UK NHS has been characterized as a ‘command and control’ system (Harrison and Moran, 2000). Largely because of this state involvement, the NHS historically has been able to keep its per capita health-care costs lower than many other Western industrialized nations. Whereas the UK spent $2231 per capita on health in 2003, for example, the US spent $5635, over twice as much. At 7.7% of GDP, UK’s health expenditure is also below the OECD average of 8.8% (OECD, 2005). However, since Labour came into power, funding for the NHS has more than doubled, with then Prime Minister Tony Blair promising to bring NHS spending up in line with the rest of Europe by 2007–08 (Department of Health, 2006).

Expenditures

Resource allocation within the NHS is determined largely through a weighted capitation formula: Local PCTs are allocated resources based on the size of their populations and adjusted for need (e.g., need will be higher in a PCT with an older caseload than in a PCT with a relatively young caseload) (DOH, 2005a).

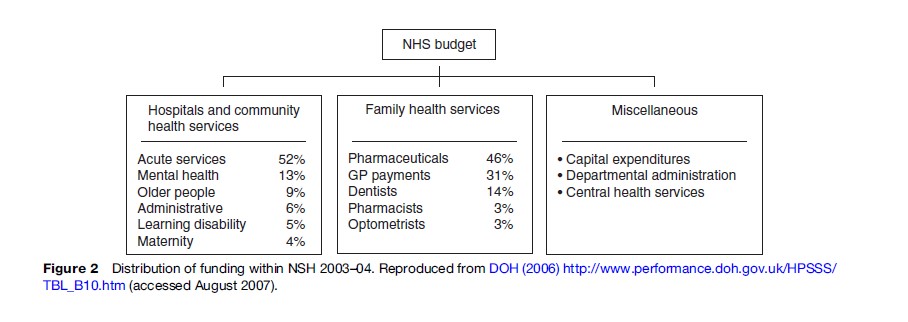

The bulk of NHS funding goes to family health services, and to hospitals and community health services, largely in the form of professional salaries (Figure 2).

Capacity And Use By Service Sector

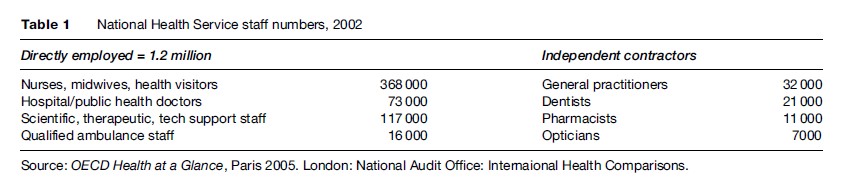

The NHS directly employs approximately 1.2 million staff and contracts with over 70 000 independent contractors, including about 32 000 GPs (Table 1).

Although the number of practicing physicians (per 1000 population) in 2003 was below the OECD average in 2003, the average annual growth rate of practicing physicians was higher at 2.4 physicians per 1000 population compared with the OECD average of 1.8 (OECD, 2005). Similarly, the number of per capita doctor consultations increased from 5.2 to 6.1 between 1990 and 2003 (OECD, 2005).

In 2002, the availability of hospital beds was slightly lower than the OECD average of 4.2 beds per 1000 population, at 3.7 beds per 1000 population (OECD, 2005). Hospital discharges, however, were higher than the OECD average of 161 (per 1000 population), at 232 discharges, representing a 15% increase since 1995 (OECD, 2005).

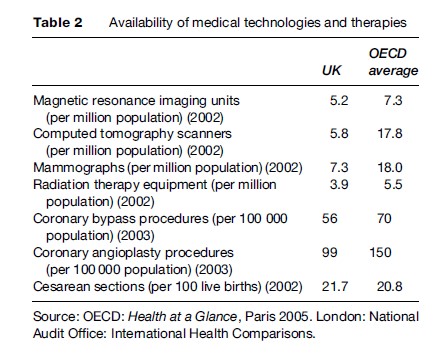

The availability of certain medical technologies and therapies also tends to be lower than the OECD average (Table 2). In 2002, for example, the NHS had 5.2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units (per million population), compared with the OECD average of 7.3.

Private Health Care

Private spending makes up about 18% of total health-care expenditure in the UK (Ham, 2004; OECD, 2005). Of that amount, roughly 13% comes from NHS user charges (e.g., for prescription medication), 8% from out-of-pocket payments for hospital care, 17% from private medical insurance, 8% for optical services, 5% for dental services, 7% for complementary medicine, and 1% for audiology services. The remaining 41% is spent on over-the-counter medicines (Keen et al., 2001).

In 2004, 686 million prescription items were dispensed in England alone, 13% of which were subject to user fees. In 2001–02, dentists had 1.8 million patient contacts (Department of Health, 2006).

In addition to traditional health-care services, an estimated 20% of the UK population also used complementary and alternative medicine totaling some £1.6 billion, with average provider fees in South West London ranging from £16.50 to £40.00, depending on factors like the duration of consultation (Ernst and White, 2000).

Approximately 11% of the UK population has private insurance which is most frequently used to bypass waiting lists, especially for nonurgent surgery. For this reason, private insurance has sometimes been criticized as establishing a two-tier system because it allows wealthier patients to effectively ‘jump the queue’ and obtain treatment more quickly.

Current Issues And Key Concerns For The NHS

As life expectancy continues to improve, innovative treatments become available, and the prevalence of chronic illness increases – particularly among ethnic minorities and low-income populations – the NHS faces great pressure to find efficient and equitable ways to ration scarce health resources, to tackle health inequalities, and to pro- actively promote health rather than retroactively respond to illness. Although these three issues are not new to the NHS, they represent some of the key challenges facing the NHS now. And even though they are treated in this research paper as conceptually distinct, readers should keep in mind that they are quite inextricably linked.

Rationing

Whereas the NHS has always explicitly aimed for universal and equitable access to care, it has never guaranteed access to a specific level of care or treatment, despite the rhetoric of comprehensive care from cradle to grave.

Thus, rationing is not new to the NHS, nor is the need for rationing likely to dissipate in the future. Although funded through taxation, the NHS nevertheless is a ‘third-party payment’ system, where care is largely free at the point-of-service. As long as health care is purchased by third parties (in this case the government) and patients are insulated from the full cost of the care they consume, there is evidence that demand for health care will exceed its supply, and rationing will be inevitable.

Rationing can occur at three different levels: the macro, meso, and micro levels. At the macro level, health planners make policy decisions that have national implications, such as the size of the total health-care budget, and, in some cases, explicit decisions about which interventions should or should not be offered. At the meso level, intermediate bodies like health authorities, PCTs, and hospitals negotiate how to allocate resources among different treatments and population groups. And at the micro level of the doctor–patient relationship, physicians decide how to allocate resources among individual patients (Coulter and Ham, 2000). At the meso and micro levels the scope for discretion depends in large part on the specificity of the decisions taken at the preceding level.

Within each of these levels, rationing can take a variety of forms and can vary in visibility. For example, though it is often not understood as rationing because it is not visible as such, rationing can occur by price and according to the ability to pay when market forces are allowed to determine resource allocation. At the other end of the spectrum is rationing by denial which is the most visible form of rationing. Other forms of rationing include rationing by selection (selecting only certain patients to receive treatment according to some exclusion criterion like ability to benefit from treatment); rationing by deflection (steering patients toward other – usually cheaper – interventions or other service sectors); rationing by deterrence (making access to treatment more difficult); rationing by delay (placing patients on a waiting list); and rationing by dilution (giving less resources to each person so that everyone gets something but not the optimal amount).

Whereas the need to ration health care is not new, the ways in which care is rationed in the NHS have changed. It is well understood that rationing has been largely implicit for much of the history of the NHS and ‘concealed beneath the cloak of clinical freedom.’ That is to say, questions about which patients got what treatment and how quickly were largely left up to physician discretion. GPs helped to contain demand at the primary care level by restricting access to secondary care to only those patients who they deemed truly required specialist care, while specialists managed demand at the secondary care level through waiting lists. As Aaron and Schwartz describe:

Confronted by a person older than the prevailing unofficial age of cut-off for dialysis, the . . . GP tells the victim of chronic renal failure or his family that nothing can be done except to make the patient as comfortable as possible in the time remaining. The . . . nephrologist tells the family of a patient who is difficult to handle that dialysis would be painful and burdensome and that the patient would be more comfortable without it.

(Aaron and Schwartz, 1984: 37)

For this reason several authors have argued that rationing went largely unnoticed for the first 30 years of the NHS. With the economic recession of the 1970s, however, came pressure to limit public spending on health care and the government’s first systematic attempt to tackle rationing head-on with the publication of its 1976 consultative document Priorities. Combined with several highly publicized cases of treatment denials, rationing was thrown into the spotlight and has been a very visible issue ever since. Some such cases involved patients who claimed to have been refused treatment due to their age, disability, or lifestyle, calling into question the wisdom and fairness of implicit rationing itself, with all the lack of transparency it entailed.

According to reviews of recent NHS policies, rationing decisions have become increasingly explicit, relying more on mechanisms like selection and denial based on overt criteria. The locus of rationing has also changed, with greater involvement by patients and advocacy groups.

Evidence-Based Medicine

The push to improve the scientific basis of clinical decision making, otherwise known as ‘evidence-based medicine,’ and the related development of analytical techniques to assess the cost-effectiveness of therapies have added another dimension to the debate over rationing. Proponents argue that because resources are scarce, funding should be reserved only for those interventions whose health benefits justify their costs. Critics argue that it is inappropriate and unfeasible to place a monetary value on life and improved quality of life.

The recent debate over the cancer drug Herceptin is a case in point. Herceptin has been shown to improve by 6% the chances that women diagnosed with a certain type of early-stage breast cancer (‘HER2’) could remain disease-free after 3 years. At an estimated cost of £20 000 per patient per year, however, its cost-effectiveness was in doubt. Swindon PCT, for example, initially decided not to offer the drug for this reason and was sued by Ann Marie Rogers, a patient who was denied the drug. The High Court ruled in her favor, and a few months later, NICE (the National Institutes for Health and Clinical Excellence) – which was established in 1999 largely to assess the cost-effectiveness of pharmaceutical drugs and interventions – concluded that Herceptin was cost-effective for selected patients.

It is important to note that evidence-based medicine is conceptually distinct from rationing. However, as Reynolds asks:

Could evidence-based medicine be used as a way of prohibiting expensive treatments which have not been formally evaluated? More importantly, could treatments be prohibited for all patients, if they are effective for only a minority of patients?

(Reynolds, 2000: 31)

Reynolds (2000) and others suggest that evidence-based medicine may, indeed, be used as a rationing tool, arguing that the trend has been to invoke evidence, drawn from medical or epidemiological research, that suggests that services or procedures previously provided as a matter of routine should be used more discriminatingly and selectively. Others also suspect that a reduction in the cost of care is high on the silent agenda of many who promote the use of guidelines and that, as a result, administrative efforts are more likely to be focused on decreasing inappropriate care than on increasing access to beneficial procedures.

Health Inequalities

Despite the principle of universal access to care that is free at the point of service, access to care under the NHS – as well as the quality of that care and health outcomes – have all been found to vary according to sex, geography, race, and socioeconomic status. For example, the prevalence of hypertension is higher among Afro-Caribbeans and South Asians in the UK than among Caucasians (Lane and Lip, 2001). Infant mortality rates are lower among infants whose fathers have professional or managerial occupations compared with their counterparts whose fathers are in manual occupations (DOH, 2005b). Fewer physicians practice in rural settings than in urban areas, and patients who live in remote areas often have trouble accessing their services.

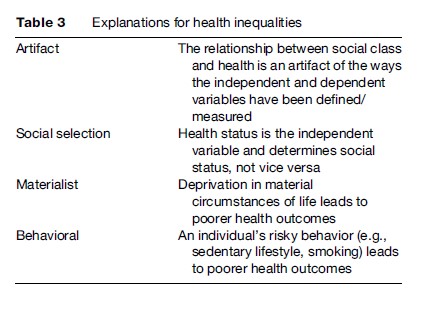

Arguably the first sustained attempt at tackling inequalities in health occurred under the 1974–79 Labour government. In 1979, a Working Party was established under the chairmanship of Sir Douglas Black to investigate the extent of social inequalities in health and to identify the pathways by which class affects health and health-care use. Its findings were published in 1980 after a new Conservative government had taken office, in what has become known as the Black Report. Although the Black Report stressed the multicausal nature of health inequalities, it prioritized materialist explanations for health disparities out of the four different pathways it identified. Its key explanations are summarized in Table 3.

The Conservative government under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, however, rejected the proposals made by the Working Group, opting for a behaviorist explanation for Britain’s health inequalities. In keeping with more libertarian political leanings, policy under Thatcher stressed individual responsibility for one’s own health outcomes and the focus was on educating the public about good health practices. The approach to tackling health inequalities was fairly similar under Prime Minister John Major.

It was not until Labour came to power in 1997 that the findings of the Black Report were taken seriously by policy makers. On taking office, the Blair government established a further inquiry into health inequalities, chaired by Sir Donald Acheson. The Acheson inquiry concluded that health inequalities were a severe and continuing problem and proposed action and a total of 39 recommendations in several policy areas to reduce them. These policies reflected a greater emphasis on materialist explanations and an attempt to improve health inequalities by reducing income inequalities. Policies have included Health Action Zones and changes to taxes and benefits (Baggot, 2004).

Since the Black Report, other theories about the precise pathways between socioeconomic status and health have been developed, such as psychosocial explanations (Marmot et al., 1991) and relative deprivation (Marmot and Wilkinson, 2001). Indeed, the precise pathways between socioeconomic status and health have proved difficult to pinpoint, and the field appears to be drifting toward more multifaceted explanatory frameworks, like the Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) multi-sectoral model, as well as life course approaches (Blane et al., 2004), which emphasize the cumulative effects of deprivation over time. Which particular theory receives popular acceptance at any given time, however, is often a function of political sympathy and ideological leanings.

Health Promotion

The cost-effectiveness of medicine as a whole has long been contested. Several historians and public health advocates have argued that increased life expectancy in the 19th and 20th centuries can largely be explained by improvements in nutrition, sanitation, and living standards rather than medical intervention (Fitzpatrick, 2000).

Regardless of the reason, life expectancy has indeed increased and living standards have risen in the UK. With that, a host of health issues have emerged, such as the ‘graying of the population,’ concomitant increases in morbidity, and the rising incidence of diseases like heart disease and diabetes which are largely caused or exacerbated by unhealthy lifestyle choices like the consumption of high-fat food, lack of physical exercise, smoking, and heavy alcohol consumption.

The rising incidence of such so-called lifestyle diseases has, once again, sparked debate about the ‘biomedical model’ of health care. Moreover, it has questioned health care’s focus on providing health-care interventions where health may be best promoted through prevention rather than treatment.

The NHS first turned to health promotion in the 1970s, and the approach within the NHS to health promotion has varied over its history. In the 1970s and 1980s, the focus was on smoking cessation, better nutrition and fitness, and preventing the spread of AIDS. In 1992, under Prime Minister John Major, the Health of the Nation White Paper was published, which, for the first time, made a distinction between a health strategy and a health-care strategy. Nevertheless, a biomedical model of disease prevention was retained, and the focus of health promotion policy under Major was the prevention of heart disease and stroke, cancer, accidents, HIV/AIDS, and the treatment of mental illnesses.

Health promotion policy under Prime Minister Blair largely continued the work of the Major government. As set out in the 1998 White Paper, Our Healthier Nation, health promotion policy under the Blair administration specifically aimed to reduce nonelderly mortality from heart disease and stroke by at least a third; to reduce accidents by at least a fifth; to reduce nonelderly mortality from cancer by at least a fifth; and to reduce the death rate from suicide by at least a sixth by 2010. As discussed earlier, however, a key difference in policy under Blair is the acknowledgment that social deprivation must be tackled as part of an overall strategy to promote the nation’s health. Indeed, ethnic minorities and individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to be disproportionately affected by these lifestyle diseases.

Critics have argued that the Labour government has not delivered on its promise to make health promotion a key focus of its health policy. Others have also criticized retaining the biomedical, disease-based approach to health promotion. Because many of these illnesses require coordinated care between the primary and secondary care levels, and across the health-care/social care divide, the government’s policy has also been criticized for not doing enough to break down the historical tripartite structure of the NHS. Indeed, one reason the expansion of the private financing initiative is controversial is that it effectively commits the NHS to 30 years (i.e., over the length of the lease) of providing hospital-based care when prevention of disease and treatment in the community may be more effective as well as more cost-effective.

Conclusion

As life expectancy increases and the population ages, the NHS will face greater demand on its scarce resources than ever before in its history. The health conditions the NHS was created to combat are not the primary health conditions that challenge British society today: Chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease have supplanted infectious diseases as the major causes of death. This changing pattern of disease will require health policy makers to think of health system design in a different way, to break through the historical divide between ‘medicine’ and ‘public health,’ and to focus on promoting health rather than responding to illness. Moreover, increasingly, at the beginning of the 21st century, important decisions are being faced about how many of the constantly appearing scientific products of medical science can be provided by public funds. More than at any stage of its history, the value and effectiveness of services in the NHS are being scrutinized. Nevertheless, because access to a wide range of modern health-care facilities has been provided by means of public funding of the NHS for so long, the NHS continues to remain a strikingly popular institution in public opinion, despite its many upheavals.

Bibliography:

- Aaron HJ and Schwartz WB (1984) The Painful Prescription: Rationing Hospital Care. Washington DC: Brookings Institute.

- Baggott R (2004) Health and Health Care in Britain. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blane D, Higgs P, Hyde M, and Wiggins RD (2004) Life course influences on quality of life in early old age. Social Science and Medicine 58(11): 2171–2179.

- Coulter A and Ham C (2000) The Global Challenge of Health Care Rationing. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

- Dahlgren G and Whitehead M (1991) Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute of Futures Studies.

- DOH (2005a) Resource Allocation: Weighted Capitation Formula. London: Department of Health Publications.

- Department of Health (2005b) Tackling Health Inequalities: Status Report on the Programme for Action. London: Department of Health Publications.

- Department of Health (2006) Community Health and Prevention: Community Dental Service activity England. http://www.performance. doh.gov.uk/HPSSS/TBL_B10.htm (accessed August 2007).

- Ernst E and White A (2000) The BBC survey of complementary medicine use in the UK. Complementary Therapy and Medicine 8: 32–36.

- Fitzpatrick R (2000) Society and changing patterns of disease. In: Scambler G (ed.) Sociology as Applied to Medicine. London: Harcourt.

- Ham C (2004) Health Policy in Britain: The Politics and Organisation of the National Health Service. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harrison S and Moran M (2000) Resources and rationing: Managing supply and demand in health care. In: Albrecht GL, Fitzpatrick R, and Scrimshaw SC (eds.) Handbook of Social Studies in Health and Medicine. pp. 493–508. London: Sage.

- The Information Centre (2006) http://www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/prescriptionsdispensed05 (accessed August 2007).

- Keen J, Light D, and Mays N (2001) Public–Private Relations in Health Care. London: The King’s Fund.

- Lane DA and Lip GYH (2001) Ethnic differences in hypertension and blood pressure control in the UK. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 94: 391–396.

- Marmot M, Davey-Smith G, Stansfeld S, et al. (1991) Health inequalities among British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. Lancet 337: 1378–1393.

- Marmot M and Wilkinson R (2001) Psychological and material pathways in the relation between income and health. British Medical Journal 322: 1233–1236.

- OECD (2005) Health at a Glance: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD. Reynolds S (2000) The anatomy of evidence-based practice. In: Trinder L and Reynolds S (eds.) Evidence-Based Practice: A Critical Appraisal, pp. 17–34. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Butler J and Calnan M (1999) Health and health policy. In: Baldock J, Manning N, Miller S, and Vickerstaff S (eds.) Social Policy, pp. 387–418. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Harrison S and Hunter DJ (1994) Rationing Health Care. London: Institute for Public Policy and Research.

- Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report (Acheson Report) (1998) London: The Stationery Office.

- Klein R, Day P, and Redmayne S (1998) Managing Scarcity: Priority Setting and Rationing in the National Health Service. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Le Grand J, Mays N, and Mulligan J (eds.) (1998) Learning from the NHS Market: A Review of the Evidence. London: The King’s Fund.

- McKeown T (1979) The Role of Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Saltman R and Von Otter C (1992) Planned Markets and Public Competition: Strategic Reform in Northern European Health Systems. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Webster C (2002) The National Health Service: A Political History, 2nd edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Whitehead M, Townsend P, and Davidson N (1992) Inequalities in Health: The Black Report and the Health Divide. London: Penguin.

- http://www.social-policy.com/ – The British Social Policy Association.

- http://www.euro.who.int/observatory – The European Observatory on Health Care Systems and Policies.

- kingsfund.org.uk/ – The King’s Fund (an independent charitable foundation working for health, especially in London).

- http://www.oecd.org/ – The OECD website.

- pickereurope.org – The Picker Institute (specialise in measuring patients’ experiences of health care and using this information to improve the provision of health care).

- dh.gov.uk/ – UK Government Department of Health (Official website of UK Department of Health, the government department responsible for public health issues).

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.