This sample Health Systems of Russia and Former USSR Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The Context Of Transition

The fall of communism led to a widespread drive for national autonomy, with most former Soviet Union (FSU) countries achieving independence shortly after 1991. This transition period coincided with radical political and economic liberalization, accompanied by expansion of market forces and building new political relationships with the United States, the European Union (EU) and its member states, China, and Iran. Some of the changes that took place reflected a popular desire to move away from the legacy of the past, while in others, external forces played a major role. In some countries, rejection of communist ideology was combined with a strengthening of nationalistic sentiment, the former being identified with Russian dominance. However, change was more often unplanned, brought about by the economic collapse arising from the disruption of traditional production and trading relationships. In some places, this was exacerbated by civil disorder.

The social consequences of the break-up of the Soviet Union were significant. In many cases, the collapse of whole industries that were no longer competitive in the global economy and disruption of long-standing trading links led to widespread poverty, unemployment, macroeconomic instability and a decline of the population’s economic and social resources. In many countries, the gross national product (GNP) declined by 50%. Almost everywhere, falling government revenues, spiraling inflation (and devaluation) meant existing public health systems started to collapse. Nominally, they continued to operate, by paying wages late and avoiding any investment in equipment and facilities. This led to an insidious deterioration in the health-care structures and ineffective functioning. In places, the collapse was particularly rapid, notably in social security protection and other public services. Migration, erosion of social networks and values, armed conflict, and the rise in high-risk behaviors such as selling sex, alcoholism, and drug use have contributed to social disruption and compounded economic insecurity. International development assistance for health in the region has been low in relation to health and economic needs (Suhrcke et al., 2005).

The countries of the FSU vary widely in terms of historical and cultural background, population homogeneity, income levels, and political processes. The Baltic States, for example, have benefited from relative political stability and have strategically positioned themselves toward European integration, becoming full members of the EU in 2004, and have established reasonably functioning market economies with effective social safety nets, along with reform of their health-care systems. In the remaining FSU countries, the situation is still one of transition. The countries of Central Asia and Caucasus (e.g., Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, and Tajikistan) have experienced significant economic crises, geopolitical pressures, ethnically motivated conflict, and political unrest, with large numbers of their populations being displaced. While countries such as Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are still a long way from establishing democratic institutions and processes and economic reform, others, such as Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, have opened their markets but not their political processes. Indeed, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are becoming increasingly isolated as a result of undemocratic regimes, repression of civil society, and controversial national policies (Rechel and McKee, 2005). Belarus and Ukraine had, until recently, been relatively isolated, though political and economic change is now occurring, if only in a somewhat stuttering manner. The economic development of some countries in the region such as Russia and Kazakhstan have benefited from access to natural resources in recent years, most notably with the escalation of oil prices. Across the region, however, socioeconomic inequities have grown alarmingly and access to public resources declined. While income differentials have grown, and a small hyperaffluent elite has benefited substantially, large sections of the population have suffered and become marginalized. The size of vulnerable populations has grown, with migrants, ethnic minorities, the homeless, and people working in the informal economy being particularly at risk.

Attempts to mount effective policy responses have been handicapped by the absence of functioning governance systems. Other than Russia, these transitional states had only limited experience in law making, good governance, and effective stewardship, and great effort has had to be devoted to the drafting of constitutions and development of democratic institutions in the early years. In addition, in Russia, the health-care system was caught up in a major process of decentralization, with 89 regions gaining varying degrees of autonomy, including responsibility for the funding and delivery of health care, at the same time as they struggled to introduce new systems of health financing.

Health And Demographic Status

The human cost of transition has been enormous. The region has experienced dramatic changes in its demographic and health indicators, which compare unfavorably with the indicators in Western Europe and the countries in central Europe. In the post-war period, the Soviet system made considerable progress in establishing universal health and education systems, implementing universal immunization programs and eradicating cholera, malaria, and typhoid based on scaling up basic interventions. As a result, until the late 1960s, many former Soviet republics achieved increasingly good health outcomes given their level of economic development. However, the health-care and health promotion systems were less effective in undertaking more complex programs required to respond to the changing disease patterns and risk factors associated with aging, urbanization and industrialization (smoking, alcoholism), and noncommunicable diseases. As a result, since the 1960s, life expectancy in most countries of the FSU did not improve in line with the rises achieved in the West (McKee, 2001). This epidemiological departure was driven largely by rising death rates from heart disease, injuries, and violence. The persistence of the previous system’s deficiencies were exacerbated by complex transition processes and resulted in worsening mortality and morbidity outcomes.

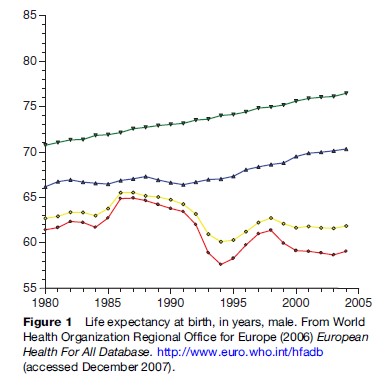

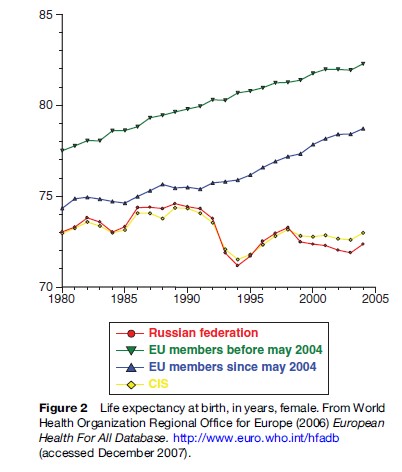

By 2004, life expectancy at birth was almost 11 years less in the countries of the FSU than in Western Europe, a gap that is still widening (Figures 1 and 2). The region is one of only two in the world where life expectancy is currently declining, with the other being sub-Saharan Africa (McMichael et al., 2004). Russia in particular has faced a major crisis in mortality in middle-aged men. The reasons for this health crisis can be attributed to lifestyle factors (binge drinking, high levels of smoking, lack of exercise, and poor nutrition). An alternative explanation is simply that these are expressions and mediators in the causal pathway, of profound psychosocial ill health (McKee, 2001). While many of the reasons for this deterioration lie outside the health-care sector, the need for effective health care that can respond to these challenges and promote health has never been greater.

The example of infant and maternal mortality illustrates how persisting poor outcomes relate to structural fault lines in the health-care system. While countries of the Soviet Union had achieved significant progress in reproductive health outcomes in the post-war period, by the 1980s, infant and maternal mortality was lagging well behind Western European levels (WHO, 2006). Despite universal access to an extensive network of maternity facilities, maternal care outcomes in Russia have failed to improve despite excess capacity, large numbers of specialists, and prolonged preventive hospitalizations in normal pregnancy (Danishevski et al., 2006b). There are extremely wide variations in clinical practice (e.g., in the rates for cesarean section and episiotomy). Some correlate with socioeconomic characteristics of mothers (rather than clinically determined need), but others correlate with equipment availability or health system structures and processes. Moreover, a culture of over medicalization combined with a lack of pragmatic and evidence-based care has resulted in an interventionist clinical practice that is both ineffective and inefficient. Although professional clinical autonomy has been fiercely protected despite centrally developed guidelines (meaning that outmoded care models often persist), methods for payment to providers have frequently resulted in distortions in care processes that maximize provider income rather than improve clinical outcomes. For example, maternal care interventions are often performed to obtain informal payments and users are hospitalized in order to sustain institutional bed capacity.

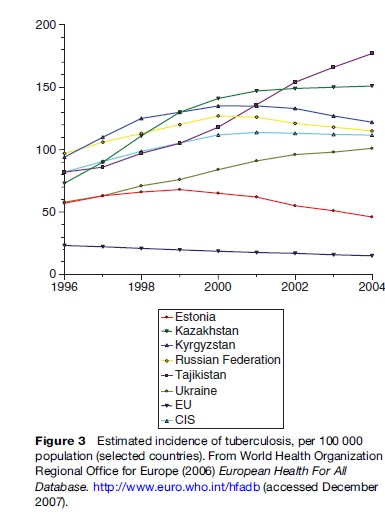

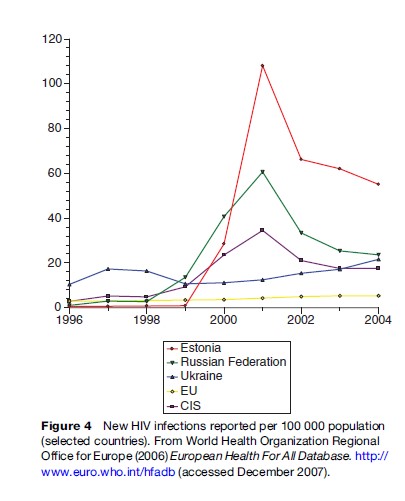

In parallel to excessive mortality and morbidity from chronic diseases, some communicable diseases are emerging as important public health threats, such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (including multidrug-resistant tuberculosis) (Figures 3 and 4).

The Pretransition Health-Care Systems (Before 1991)

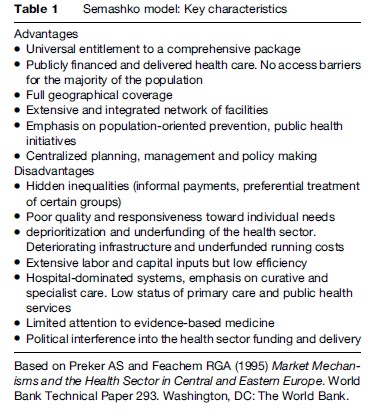

The pretransition health-care system in the former Soviet Union, also known as the Semashko model (Nikolai Semashko (1874–1949) was a member of the Bolshevik Party who became USSR’s People’s Commissar of Public Health in 1923 and was instrumental in setting up the Soviet model of health care.), sought to provide universal access through an extensive network of facilities and was among the most visible achievements of the USSR. Evidence on system functioning and health outcomes predating the end of the communist regime is limited, but there are indications that, at least formally, the health systems shared considerable uniformity.

Before the Russian Revolution, health care in rural areas was extremely limited, with some provision by local government and charitable donations. Living conditions and health in many remote areas remained very poor. Following the revolution, public health became a political priority because the poor health of the population was seen as endangering the success of the revolution, with the already high death rates increased further by epidemics of communicable diseases.

The basic elements of a health-care system in the USSR began to be put in place in the 1920s. These reforms accelerated during the late 1940s and 1950s through the establishment of a network of facilities that reached out into the most remote settlements, providing basic coverage to almost the entire population. The Soviet-style health-care model was replicated throughout Central and Eastern Europe after the Second World War. The health-care systems were publicly financed, through general taxation, with the state owning the facilities and providing all health services (Table 1). Access to care was free at the point of use. The formal private sector was nonexistent. The system was labor-intensive, largely because it was possible to keep the wages of health professionals in the health sector low when the state was the monopoly employer. In Russia, the health-care system focused in particular on mothers and children and the control of infectious diseases, reflecting the importance given to boosting population growth. Infant and maternal mortality fell rapidly, in part due to the expanded healthcare system but also because of achievements in other sectors, such as nearly full employment and improved living conditions, albeit achievements made at a huge human cost, with those who stood in the way of progress being sent to the gulag. Inevitably, the quality of care varied; it was always better in the cities than in villages. But compared to what had existed before, for most people it was a considerable improvement.

Health systems were both integrated and vertically structured, with precisely defined responsibilities for each level of care. Services were provided through extensive networks of facilities covering designated catchment areas. The primary care level consisted of polyclinics (and subordinate rural ambulatories) typically staffed by district physicians and several specialists with basic training. Rural ambulatories and health posts often employed feldshers or community-based health workers who often served state collective farms. Primary care facilities were subordinated to district-level and regional hospitals for secondary care and referral institutes for tertiary care. While polyclinic care was relatively accessible, with free access to local providers, obtaining treatment at higher-level institutions may have been dependent on patronage and informal payments, although data is anecdotal. However, the health-care system had a strong hospital-based and specialist care orientation, since primary care providers had only basic skills and equipment and did not function as gatekeepers (indeed incentives to refer existed).

There were also separate specialist structures, for example dispensaries, which ran vertical disease control programs dedicated to sexually transmitted diseases, mental health, tuberculosis, cancer, etc. These were in addition to sanitary-epidemiological stations responsible for public health initiatives, licensing of institutions, and infectious diseases surveillance. These had separate management structures and information systems. There were also parallel services for people working in the defense industries and the military, transport sector, penitentiary systems, and others.

The system was centrally planned and usually national or regional levels of state administration were responsible for management, resource allocation, and regulation. In Russia, the health system was regulated by a Ministry of Health and its branches at republican and regional level, through a centralized system of decrees (in Russia prikaz) enacted nationally, regulating mainly the structure of the health system, providing norms for staffing, facilities, and operational procedures such as frequency of visits and procedures (e.g., prenatal visits, blood tests). The Ministry of Health prikazes also set treatment standards, although these were often vague and provided general guidance rather than specific directions for clinical care and were often based on advice from leading specialists and traditions rather than upon the emerging internationally accepted paradigm of evidence-based medicine.

Health sector financing was determined on a residual basis (after the needs of other sectors had been met) and was below that of other industrialized countries, at 4% of GDP on average in the 1990s compared to the OECD average of over 6%. Furthermore, resource allocation of inefficient, based on fixed norms for the number of staff and beds per population, on a historical basis, and not taking into account volumes or quality of clinical activity or public health impact. These regulatory and financing arrangements led to a continuing overmedicalization of the health system.

Even during the communist era, access to good-quality care was increasingly inequitable. Members of the Communist Party elite, as well as sectors with parallel health systems, such as the military and employees of some state industries, had privileged access to care and pharmaceuticals that were of much higher quality than the average. There are indications that access to good-quality care was dependent on the use of connections or offering gifts. However, the formal entitlement to service was still in existence and was (and remains) clearly stated in the constitutions of most countries. The system could not support interventions that were becoming increasingly available in the West, in part because of lack of funds but also because of restrictions on imports from Western countries that were concerned about the use of advanced technology for military purposes.

By the late 1980s, the system was struggling to respond to the needs of the population and was becoming increasingly ineffective, inefficient, and obsolete (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2006) After 1991, in many places the system collapsed in the face of serious financial shortages, triggering a huge increase in out-of-pocket payments, and reducing coverage of essential interventions.

Health Care Systems And Reform Since Independence

Current Status

The subsequent variations across the health-care systems of countries in the region reflect diverse political and economic trajectories. Generally, health-care systems have experienced difficulties since the 1980s, exacerbated by their countries’ shift to market economies (McKee et al., 2002). The political and economic transition as well as declining government financing and support for reform has led to dramatic depletion of resources in the health-care systems across the region. While health-care spending in Russia has remained relatively stable, in Georgia and Armenia it was in the range of 1–2% of GDP throughout the 1990s. In particular, public health expenditure experienced profound declines. With the collapse in public funding, reliance on out-of-pocket payments by users to access care and pharmaceuticals has grown. Formal and informal out-of-pocket payments to obtain good-quality health care have become increasingly common across the region, although to different degrees (Lewis, 2002; Falkingham, 2004). For the poor, out-of-pocket expenditures often represent a barrier to care, thus restricting demand (Balabanova et al., 2004). With limited investment in infrastructure maintenance, this pattern looks set.

Unlike the situation in many other parts of the world, where reduced access to the health-care system has arisen following often donor-driven policies to implement user charges, in the FSU region it is a consequence of dramatically reduced resources, in systems formerly reliant on extensive growth. Wider policies of economic liberalization, the introduction of market mechanisms replacing traditional state functions, deregulation, and decentralization have also influenced the architecture of reforms. Despite official commitment to guarantee universal coverage (with most insurance packages covering virtually all medical conditions apart from cosmetic surgery and dentistry), the reality is that profound barriers to access exist for substantial populations.

Despite changes in funding in recent years, from taxation to insurance, most health-care facilities continue to receive budgets allocated according to number of beds and staff, rather than volume or quality of services (Danishevski et al., 2006a). Moreover, public health systems remain heavily dependent on parallel vertical programs. Medical associations are still not in a position to act as self-regulatory bodies. In addition, because of an underdeveloped civil society and low awareness of public sector entitlements, patients have limited opportunities to question clinical decisions and cost of care. There has been some, though variable penetration of the principles of evidence-based health care that were previously rejected by the traditional Russian scientific orthodoxy.

Health-care staff-to-population ratios continue to be high, with wide variation across the region, a paradoxical position of overcapacity and ineffective function. For example, in Russia, formally little reduction in maternal facilities capacity has been observed despite a large decline in the birth rate (WHO, 2006), although capacity is not used as intended. The skill mix, especially in urban settings, remains in favor of training and retaining physicians, rather than midwives, nurses, and auxiliary staff, or developing new, innovative approaches through training and employment of nurse practitioners. In contrast, in rural areas, due to a decline in personnel and skills, in practice, unsupported staff with narrow skills are often taking on significant responsibilities (Danishevski et al., 2006b). Despite high staff capacity, health services continue to be unresponsive to user needs.

Health System Reform

Over the past 15 years, all countries in the region have implemented wide-ranging reform programs of healthcare financing and delivery of care models. Some countries have implemented comprehensive reform programs with monitoring and evaluation components (e.g., MANAS in Kyrgyzstan), while others have adopted a piecemeal approach (Russia, Ukraine). Despite differences between countries, given the similarities in the pretransition health systems, most countries have faced similar challenges. Several major reforms have taken place in the region.

- The first radical health financing reform was a move from tax-based to social insurance systems, seeking to cover the whole population with a comprehensive package of services. The compulsory social insurance model (based on the Bismarckian sickness funds system) has formally upheld the principle of universal access to care, while seeking to mobilize resources given the narrow tax base, to safeguard health-care funding flows, and promote strategic purchasing. However, its most explicit objectives were to improve transparency and accountability of health sector financing and its dependence on short-term political priorities. The shift from central government budgets to compulsory health insurance has involved varying degrees of competition and state subsidy, as well as expansion of out-of-pocket payments (Lewis, 2002). In most countries, there is a separation of purchasing and provision, often with health insurance funds acting as third-party insurers contracting care.

However, the shift to a social insurance model requires complex systems, and this has been hampered by poor administrative capacity and information systems, and high transaction costs. It also failed to significantly increase resources for health care, as shown by the example of Kyrgyzstan and Georgia (Bonilla-Chacin et al., 2005). Moreover, sustaining funding levels has relied on budget subsidies. In many cases, an employment-based health insurance has been incompatible with patterns of informal employment, rural poverty, and non-cash economies, and certain vulnerable or marginalized groups have been consistently excluded. The ability of the governments to back insurance systems deficits has been limited because of macroeconomic shocks.

The countries in the Caucasus (Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan) have implemented microinsurance schemes for rural, isolated populations – which are difficult to cover in a formal insurance system – relying on community management and solidarity. While these schemes have provided a vital first-line service, the scope and quality of care is basic (e.g., excluding care for common chronic conditions), participation remains low, and scaling-up is proving a challenge (Poletti et al., 2007). The schemes also suffer from generic problems with insurance, such as small risk pools, lack of cohesive communities, poor administrative capacity, and poor ability to attract subsidies.

- Changes to delivery of primary care across the region include development of general practice (family medicine) to replace the former polyclinic-based model. Reform also included introducing new types of clinical training and primary care financing, usually capitation-based. However, despite efforts to shift the health system orientation toward primary care with a gatekeeping function, in reality progress has been slow. In Russia, where efforts to recruit and train generalists has been considerable, newly trained professionals commonly return to practice in polyclinics where they are not provided with resources or incentives and often revert to old models of practice, or they face unemployment (Rese et al., 2005). Professional demarcations persist. For example, in Kyrgyzstan and Georgia, despite physicians receiving training in managing diabetes and other complex chronic diseases prevalent among the population they serve, in practice all care continues to be provided by specialists (Hopkinson et al., 2004).

- Management training for administrators remains limited and systems of resource allocation and reporting inherited from the Semashko model are still in place, with important implications for the sustainability of reform models and the introduction of incentives to engineer change (Danishevski et al., 2006a). Managerial autonomy is very restricted. Policy making in the health sector remains heavily influenced by political power.

- Efforts to create a private sector or liberalize existing provision have largely been limited to the pharmaceutical sector and out-patient care in urban settings, where the ability to pay is greater. The private sector remains limited in most countries due to deficiencies in voluntary health insurance such as narrow coverage, limited capacity, unaffordable premiums, and a lack of trust.

- Most countries have sought to decentralize their health-care systems. Within Russia, there has been a process of decentralization (Danishevski et al., 2006a), allowing regional and municipal administrations to fund and deliver health care while still formally observing the norms established by the Ministry of Health. There are also numerous local, often donordriven, initiatives. The move to decentralization and regional autonomy, with the intention of creating more locally responsive, although less coordinated systems, led to declining stewardship of the national institutions, such as the Ministries of Health and public health authorities. Duplication of functions at different levels of the system has resulted as facilities are financed and managed by different principals, resulting on occasion in a lack of coordinated policies and practice. Linkages between the multiple horizontal and vertical (disease-specific) services have been further weakened, with the effect particularly visible in the area of infectious disease control (HIV and TB), where concerted action between the specialized facilities and the general system has been particularly difficult to achieve.

- Professional organizations of physicians have been reestablished and have begun to play a role in training, licensing, and quality control as well as becoming partners in health sector reform through setting clinical guidelines and advising on contracts of packages of care. Associations of nurses and other mid-level staff have been less influential. Patient organizations have also emerged, but they play a marginal role in national policy making and mostly provide health information, education, and small-scale service delivery to particular constituencies.

Despite ambitious and in many cases donor-financed reform, in most of the post-Soviet Union, the health systems retain much of their previous orientation, structures, and ethos. With some exceptions (rationalization of hospitals in Kyrgyzstan), reforms have done little to address inefficiencies in the inherited system and improve provider incentives. Radical reform initiatives are often placed in the context of old resource allocation patterns, institutions, and attitudes, such as with the attempts to implement general practice in Russia, without addressing working conditions and support at the system level (Rese et al., 2005).

In many countries, however, it is not the planned changes that have had greatest impact but those that were unplanned. In particular, many have seen large increases in informal payments (Lewis, 2002). In some, social safety nets have been eroded with catastrophic illness bringing long-term impoverishment for whole families.

Access To Health Care: The User’s Perspective

There is significant evidence that since the transition, people living in this region have experienced barriers to effective health care. A study in eight of the former Soviet countries demonstrated the extent to which the principles of universal access that underlined the former Soviet health systems have eroded (Balabanova et al., 2004). One in five of those who had experienced an episode of illness that they felt would have justified seeking health care did not seek it. This percentage was lowest in Belarus, at 9%, a country where change has been less radical, and was highest in Armenia (42%) and Georgia (49%), both countries that have experienced dramatic economic declines as well as civil conflict, and where the healthcare systems effectively collapsed during the 1990s. Even symptoms such as chest and severe abdominal pain would often be self-treated using either traditional remedies, for example herbal and alcohol-based remedies, or by direct purchase of pharmaceuticals. There is little standardized and comparable data in the CEE/FSU region on the use of traditional (nonbiomedical) healing systems, and these usually vary between and within countries. Prior to transition, these were mainly used to supplement biomedical treatments and were not perceived to be credible substitutes. However, evidence (as cited above) suggests that traditional remedies are increasingly chosen as a more affordable option. Self-medication, both with traditional remedies and with biomedical drugs, is often a strategy to bypass the mainstream health services, which tend to be associated with high access costs.

Informal out-of-pocket payment is frequent. Almost one-third of people had paid or given a gift at their most recent consultation. Again, this varied among countries. In Georgia and Armenia, 65% and 56%, respectively, had paid out of pocket, while in Belarus and in Russia the figures were 8% and 19%, respectively. Informal coping strategies, for example, for urgent hospitalization, such as use of connections (37%) or offering money to doctors or nursing staff (29%), were seen as acceptable strategies. Those who needed care but did not receive it were most often older, typically over 65, with lower education. This was a group that was disadvantaged in other ways, with worries about their financial situation and fewer household assets. They were also least likely to have family support networks in place. Those living in cities were better off, being 20% more likely to obtain care after taking account of their socioeconomic circumstances.

Access to care varies across many of the countries that emerged from the USSR. Access to even quite basic care is highly variable depending on the socioeconomic circumstances of individuals, public sector resources, reform programs, and government support.

During the Soviet period, it was impossible to study socioeconomic inequalities in health status and expenditure. Although such research is now possible, it remains rare, with the notable exception of Russia. In contrast to the media attention devoted to political and economic changes in this region, the impact of the transition on the health of individuals and families remains poorly recognized. Yet what evidence exists paints an alarming picture. In a single year, one in every 160 households in Kyrgyzstan and one in 25 in Ukraine faced catastrophic expenditure due to health costs (Xu et al., 2003). In Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, substantial inequalities have been documented in access to care as services become unaffordable for the poor (Falkingham, 2004; Rechel and McKee, 2005).

Survey data on health-care use and the expenditure involved are increasingly available (data from the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey is available from 12 series of consecutive surveys, the World Bank Living Standards Measurement Study in Central Asia, etc.). However, these surveys often exclude the experiences of the most disadvantaged populations (Hopkinson et al., 2004). The case of abortion also demonstrates how gaps in access to care can occur even where overall utilization is high (Parkhurst et al., 2005). Abortions have been widely used as a method for contraception in the former Soviet Union and remain at high levels. Although abortion is legal and generally accessible, abortion complications account for approximately 25% of maternal deaths, with two-thirds of this reportedly resulting from illegal abortions. Certain groups such as migrants and those without a permanent address are particularly at risk and may face barriers in accessing care due to bureaucratic obstacles and informal pressure to pay. Mothers under 18 remain under the care of pediatric services, which have poor links to sexually transmitted infections (STI), maternal, and reproductive services. Awareness of contraception is high, but in practice it is often inaccessible, resulting in high rates of abortion.

The understanding of the health systems in the FSU, the impact of reform, and the ability to draw lessons and inform future policy direction remain in their infancy. For no population groups is this more apparent than for the poorest sections of these changing societies.

Emerging Challenges

Responding To Chronic Disease

The health systems in the region face considerable challenges. The rising burden of chronic noncommunicable disease requiring reliable life-sustaining treatment requires complex and innovative system responses. It is increasingly demonstrated that adequate financing and appropriate infrastructure is only the starting precondition to achieving good service. Integrated care involving coordination and effective communication between multidisciplinary teams, at different levels of the health system is essential for effective chronic disease management. Good governance and accountability is crucial to achieve universal and responsive patient-centered care. Active involvement of patients and their representatives is also key to successful chronic disease management. However, as described above, these needs are at odds with the Soviet-style top-down management and paternalistic culture in the FSU, a pattern that persists in many countries.

Although there are well-established models for chronic disease management internationally, their application to the FSU countries appears increasingly problematic. Patterns of clinical practice that are based on the labor-intensive model remain in place, and there is a lack of investment in appropriate skills, equipment, facilities, and knowledge to implement more effective chronic care models. Management of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy, or asthma is particularly poor at the primary care level and most chronic care is conducted by highly specialized staff with no means of achieving continuity of care.

Some diseases can illustrate health system failures. For example, death rates from diabetes have been increasing markedly in many FSU countries. In Ukraine, verbal autopsy interviews with relatives of those who had died prematurely show that despite the maintenance of access to care, people with diabetes suffered from numerous problems, with shortages of drugs and equipment and poor-quality care (Telishevska, 2001). A similar picture has been described in Kyrgyzstan (Hopkinson et al., 2004). Chronic-care systems are fragmented, and linkages between levels of care and different specialists are lacking. As a result, clinical outcomes have worsened, with admissions of patients with complications or in coma, especially among those living in rural areas, on the rise.

The reasons for this deterioration in clinical outcomes are complex. In central Asia and in Russia, despite the comprehensive donor-funded programs for training family physicians, new practitioners have little practical knowledge in managing diabetes and other chronic conditions (Hopkinson et al., 2004). The Soviet health-care system was never geared toward managing such conditions at the primary care level, especially in rural areas. Although change was being implemented, with a well-designed program in the major cities, too often the necessary institutional and sectoral connections had not been made. For example, investment in training in management of diabetic complications is not embedded in the system through reformal channels and availability of necessary equipment where required. As noted, professional resistance plays a part along with unsupportive institutional environments. Linkages between social services and health systems are weak, complicating the pathways to the treatment and obtaining the benefits to which users are entitled.

In addition, major problems with access to pharmaceuticals after the collapse of the FSU persist. Despite access to insulin often being funded by donors in a range of countries, in some places there have been major bottlenecks in procurement and distribution of drugs (Hopkinson et al., 2004).

Responding To Communicable Disease

In the 1990s most countries in the region experienced rising rates of tuberculosis and HIV, and in some countries re-emergence of malaria, diphtheria, and cholera (Kyrgyzstan) (WHO, 2006). While most central European countries have managed to retain control of HIV, Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine are struggling. Although a decade ago the countries of the western CIS were relatively untouched by this infection, the epidemiological trajectory in the region is now the steepest in the world (European Health For All Database, 2006). It has been estimated that one million of Russia’s 143 million inhabitants may be infected. Highly vulnerable, marginalized populations have been acquiring HIV in unprecedented numbers. This is caused by increases in poverty, a drop in income, and deteriorating social benefits, including housing, as well as migration, increasing numbers of drug users and commercial sex workers, limited awareness of risk factors, and a rise in co-infections (STI, TB).

Public health systems are struggling to respond to HIV and tuberculosis. Initial responses focused on widespread population testing, but this was not linked to any strategic goal. Most individuals diagnosed with HIV were left without hope. For a few individuals, intermittently available monotherapy with antiretrovirals was offered. Since HIV treatment for all has become part of global political rhetoric (if not reality), determinations of who should receive treatment, the consequences of drug-resistant HIV, and the challenge of managing, resourcing, and coordinating prevention activities as well as treatment programs is proving a formidable challenge. Generally, control of communicable diseases is hampered by inadequate surveillance and diagnostic systems, limited capacity (infrastructure and skills) in delivering effective public health interventions, despite the existence of sanitary epidemiological stations and vertical subsystems within the broader health system. This challenge is not helped by the vertical, disease-specific nature of the HIV-control health system structures.

After the transition, in most countries, testing and treatment for HIV, TB, and STI is performed in a range of institutions (regional AIDS centers, narcology departments, dermatology and venereology, prison service, sanitary epidemiological stations) as well as in the private sector, with differing funding and delivery arrangements. While considerable variations exist across the region in terms of control efforts and epidemiological trajectories, the lack of integration between, for example, testing and treating, penitentiary and civilian, and HIV care and TB control systems, means that integrated, patient-centered care does not exist. This fragmentation of care, and the inability to trace and retain people in the health system, and to implement system-wide interventions involving different sectors such as social services, prison health services, police, and education has its roots in the pretransition public health-care model where few incentives were built in to ensure improvements in clinical outcomes.

In the case of tuberculosis, surveillance systems are struggling in the face of underfunding, reliance on obsolete systems and infrastructure, and a lack of epidemiological capacity. Cure rates have fallen since the mid-1980s, and erratic treatment adherence coupled with uncertain antituberculosis drug supplies have contributed to the emergence of multidrug-resistant TB. Inadequate linkages between parallel health systems, for example between civilian and prison institutions, left many patients to fall between the gaps (Coker et al., 2003). Administrative inertia, combined with high-level skepticism regarding the evidence base for DOTS (the World Health Organization’s TB control strategy), cultural resistance to clinical standardization, and a reluctance to forego radiologically based approaches to diagnosis, meant that internationally accepted approaches to control were slow to be embraced. In recent years, Russia, and to a lesser degree Ukraine and Belarus, have started to pilot DOTS approaches, but with a heavy dependency upon external aid. DOTS has not been embedded systemically, with implementation largely supporting vertical approaches to disease control that are not integrated into wider health systems; managerial and financing systems hinder effective change (for example, because payment systems create perverse incentives and do not reward performance). WHO-advocated models may be unsustainable if donor support dries up (Atun et al., 2005; Marx et al., 2007).

The lack of intersectoral collaboration is particularly vital in the failure to support identification and treatment of marginalized groups, such as prisoners, people without passport registration, and the homeless (Coker et al., 2003). In the FSU, HIV/AIDS infection is concentrated among vulnerable and marginalized groups such as injecting drug users (IDUs), commercial sex workers, and prisoners, who often lack access to basic services. These groups are often stigmatized and discriminated by health staff, and their needs are not adequately addressed, causing poor adherence to treatment and lack of trust in the public systems. This is a major problem in assessing the scale of infection, detection of new cases, and treatment. There is limited collaboration with the civil society in targeting such groups (Atun et al., 2005), although in some countries such as Kyrgyzstan, NGOs act as service providers for marginalized populations (e.g., IDUs).

As in treatment of chronic disease, communicable disease management such as tuberculosis relies on frequent and prolonged hospitalizations, mostly aimed at increasing treatment adherence and retaining patients within the system, sustaining institutional funding (allocated according to existing infrastructure and bed occupancy), or to provide social (rather than medical) care for highly marginalized populations.

Conclusion

The public health consequences of the break-up of the Soviet Union have been profound. Since 1990, poverty levels have grown, income inequalities have widened, and marginalized populations have become more vulnerable. In addition, migration, erosion of social networks and values, armed conflict, and the rise in high-risk behaviors such as selling sex, alcoholism, and drug use have contributed to social disruption and resulted in deteriorating health status. The picture, however, has not been the same across all countries. Countries of the FSU vary widely in terms of historical and cultural background, population homogeneity, income levels, and political processes. The Baltic States, for example, have benefited from relative political stability, have grown economically, and are now members of the European Union. At the other extreme, the countries of Central Asia have experienced significant economic crises and political instability, with dire public health consequences. Other countries, most notably Russia, have achieved political stability and benefited from its natural resources in recent years, particularly with oil prices at an all-time high, but have struggled to reform its public health system. Overall, compared with Western Europe, health indicators have deteriorated markedly in the FSU.

The pretransition health-care system of the FSU has been largely inadequate in terms of the newly emerging demands made upon it, be they the consequences of alcohol consumption and very high death rates among middleaged men, the threat of multidrug resistance because of fractured connections between different elements of the tuberculosis control service, or a coherent evidence-based response to the HIV epidemic among IDUs.

Access to care has been challenged by reforms that have included a shift from a taxation-based system to an insurance-based system, while budgetary support has been maintained for rigid, highly verticalized structures. Patient access to care is less equitable than before the collapse of the Soviet Union in many countries. The vertical structures help perpetuate narrow skill sets among professional health-care workers. The ratio of doctors per capita in much of the FSU is high, but the skills they hold are narrowly specialized, meaning that integrated, multidisciplinary patient-centered care remains a challenge to deliver.

The health systems of the FSU are, as are the countries’ political, economic, and cultural contexts, in a state of transition. For some, this transition will be relatively painless. For others, it will be a painful process, affecting most acutely people already socially marginalized and living in poverty.

Bibliography:

- Atun RA, Samyshkin YA, Drobniewski F, et al. (2005) Barriers to sustainable tuberculosis control in the Russian Federation health system. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83: 217–223.

- Balabanova D, McKee M, Pomerleau J, Rose R, and Haerpfer C (2004) Health service utilisation in the former Soviet Union: Evidence from eight countries. Health Services Research 39: 1927–1950.

- Bonilla-Chacin ME, Murrugarra E, and Temourov M (2005) Health care during transition and health systems reform: evidence from the poorest CIS countries. Social Policy and Administration 39(4): 381–408.

- Coker RJ, Dimitrova B, Drobniewski F, et al. (2003) Tuberculosis control in Samara Oblast, Russia: Institutional and regulatory environment. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 10: 920–932.

- Danishevski K, Balabanova D, McKee M, and Atkinson S (2006a) The Fragmentary Federation: Experiences with the decentralised health system in Russia. Health Policy and Planning 21(3): 183–194.

- Danishevski K, Balabanova D, McKee M, and Parkhurst J (2006b) Delivering babies in a time of transition in Tula, Russia. Health Policy and Planning 21(3): 195–205.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2006) European Health For All Database. http://www.euro.who.int/hfadb (accessed December 2007).

- European Observatory on Health Systems Policies (2006) Health Systems in Transition Country Profiles. http://www.euro.who.int/observatory/Hits/TopPage (accessed December 2007).

- Falkingham J (2004) Poverty, out-of-pocket payments and access to health care: Evidence from Tajikistan. Social Science and Medicine 58: 247–258.

- Hopkinson B, Balabanova D, McKee M, and Kutzin J (2004) The human perspective on health care reform: coping with diabetes in Kyrgyzstan. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 219: 43–61.

- Lewis M (2002) Informal health payments in central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union: issues, trends and policy implications. In: Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J, and Kutzin J (eds.) Funding Health Care. European Observatory on Health Care Systems Series. Open University Press.

- Marx FM, Atun RA, Jakubowiak W, McKee M, and Coker RJ (2007) Reform of tuberculosis control and DOTS within Russian public health systems: an ecological study. European Journal of Public Health 17: 98–103.

- McKee M (2001) The health effects of the collapse of the Soviet Union. In: Leon D and Walt G (eds.) Poverty, Inequality and Health, pp. 17–36. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- McKee M, Healy J, and Falkingham J (2002) Health Care in Central Asia. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- McMichael AJ, McKee M, Shkolnikov V, and Valkonen V (2004) Mortality trends and setbacks: Global convergence or divergence? Lancet 363: 1155–1159.

- Parkhurst J, Danichevski K, and Balabanova D (2005) International maternal health indicators and middle-income countries: Russia. British Medical Journal 331: 510–513.

- Poletti T, Balabanova D, Ghazaryan O, et al. (2007) The desirability and feasibility of scaling up community health insurance in low-income settings – Lessons from Armenia. Social Science and Medicine 64(3): 509–520.

- Preker AS and Feachem RGA (1995) Market Mechanisms and the Health Sector in Central and Eastern Europe. World Bank Technical Paper Number 293. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- Rechel B and McKee M (2005) Human Rights and Health in Turkmenistan. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Rese A, Balabanova D, Danishevski K, McKee M, and Sheaff R (2005) Implementing general practice in Russia: Getting beyond the first steps. British Medical Journal 331: 204–207.

- Suhrcke M, Rechel B, and Michaud C (2005) Development assistance for health in central and eastern European Region. Bull World Health Organ 83(12): 920–927.

- Telishevska M, Chenet L, and McKee M (2001) Towards an understanding of the high death rate among young people with diabetes in Ukraine. Diab Med 18: 3–9.

- Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, and Murray CJ (2003) Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 362(9378): 111–117.

- Afford CW (2003) Corrosive Reform: Failing Health Systems in Eastern Europe. Geneva: International Labour Organisation.

- Atun RA, Samyshkin YA, Drobniewski F, et al. (2005) Barriers to sustainable tuberculosis control in the Russian Federation health system. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83: 217–223.

- Balabanova DC, Falkingham J, and McKee M (2003) Winners and losers: The expansion of insurance coverage in Russia in the 1990s. American Journal of Public Health 93(12): 2124–2130.

- Coker RJ, Atun R, and Mckee M (2004) Health care system frailties and public health control of communicable diseases on the European Union’s new eastern border. Lancet 363: 1389–1392.

- Davis C (1983) Economic Problems of the Soviet Health Service: 1917–1930. Soviet Studies 35(3): 343–361.

- Field MG (1957) Doctor and Patient in Soviet Russia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Field MG (1999) Reflections on a painful transition: From socialized to insurance medicine in Russia. Croatian Medical Journal 40: 202–209.

- Field MG and Twigg JL (eds.) (2000) Russia’s Torn Safety Nets: Health and Social Welfare During the Transition. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Figueras J, McKee M, Cain J, and Lessof S (eds.) (2004) Health Systems in Transition: Learning from Experience. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- Krug P (1976) The Debate over the Delivery of Health Care in Rural Russia: The Moscow Zemstvo, 1864–1878. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 50: 226–241.

- Prager KM (1987) Soviet health care’s critical condition. The Wall Street Journal 29 January 1987, p. 28.

- Shishkin S (1999) Problems of transition from tax-based system of health care finance to mandatory health insurance model in Russia. Croatian Medical Journal 40: 195–201.

- Tkatchenko E, McKee M, and Tsouros AD (2000) Public health in Russia: The view from the inside. Health Policy Planning 15: 164–169.

- Twigg JL (1999) Regional variation in Russian medical insurance: Lessons from Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod. Health Place 5: 235–245.

- http://www.euro.who.int/observatory/Hits/TopPage – European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Health Systems in Transition: Country Profiles.

- http://www.euro.who.int/observatory/Publications/20020524_26 – European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Eurohealth.

- http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/ecohost/ – London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, European Centre on Health of Societies in Transition (ECOHOST).

- http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/rlms/ – The Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (RLMS).

- http://www.unicef-icdc.org/resources/ – UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, TransMONEE database.

- http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/ECAEXT/0,contentMDK:20627214 pagePK:146736 piPK:146830 theSite PK:258599,00.html – The World Bank, Growth, Poverty, Inequality in Europe and Central Asia (ECA). Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

- http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/ECAEXT/0, menuPK:258604 pagePK:158889 piPK:146815 theSitePK:258599,00.html – The World Bank, Europe and Central Asia.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.