This sample Homelessness and Health Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper focuses on homelessness from a public health perspective – its prevalence, its relationship to specific health conditions, and various interventions intended to ameliorate homelessness and the health problems with which it is associated. Homelessness has important consequences for public health. First, homelessness contributes to elevated morbidity and mortality by increasing the risk of acute and chronic health conditions among homeless persons. In addition, a variety of health and mental health conditions place individuals at heightened risk of homelessness. Furthermore, homelessness increases the risk of disease in the nonhomeless population by contributing to the diffusion of infectious diseases. Finally, homeless persons may place a large burden on the public health delivery system because of their often high levels of need for acute care, and their lack of access to regular sources of routine medical care. Although homelessness is widespread in developing countries, where it is frequently associated with extreme poverty, natural disasters, war, and forced relocation, it is also distressingly common in the industrialized world including the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, and Japan. Our discussion focuses primarily on homelessness in the United States and other high-income countries since most of what is known about its occurrence and its association with health derives from research carried out in these parts of the world.

Defining Homelessness

Sociological research in the United States and the United Kingdom has traditionally stressed social disaffiliation, or the attenuation of connections to social structures such as family, employment, and community as key concepts in the definition of homelessness. More recent definitions of homelessness, however, tend to emphasize residential status. Such definitions, which are more easily operationalized, have greater utility for social and health services policy formulation. For example, the following definition of a homeless person was developed for the McKinney Homeless Assistance Act of 1987, one of the earliest major federal initiatives responding to the growing problem of homelessness in the United States. This definition, which excludes those who are ‘doubling up’ with housed persons or living in substandard housing, focuses instead on so-called ‘literal’ homelessness:

- An individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate night-time residence; and

- An individual who has a primary night-time residence that is: a supervised publicly or privately operated shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (including welfare hotels, congregate shelter, and transitional housing for the mentally ill); an institution that provides a temporary residence for individuals intended to be institutionalized; or a public or private place not designed for, or ordinarily used as, regular sleeping accommodations for human beings.

European policy analysts have recently developed a broader and more complex definition that allows for a continuum of homelessness ranging in decreasing severity from ‘rooflessness’ to inadequate housing (Edgar et al., 2004). These categories (which are further classified into 16 subcategories) are:

- Roofless – Living in a public space or night shelter;

- Houseless – Living in a hostel, institution, or other temporary accommodation;

- Insecure housing – Living in supportive accommodation where tenancy is dependent upon accepting social services; living temporarily with family or friends;

- Inadequate housing – Living in temporary, overcrowded, or substandard dwelling.

The Prevalence Of Homelessness

Despite significant methodological challenges to obtaining precise estimates, it is clear that homelessness is distressingly common in many high-income countries. In the United States, for instance, the most reliable estimates place the number of currently homeless persons between 2.3 and 3.5 million, while approximately 7% of adults in the United States have experienced at least one episode of literal homelessness at some point during their lifetime.

Other data suggest that the prevalence of homelessness among specific high-risk populations, primarily persons with severe mental disorders, is considerably higher. For instance, a study of all persons with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression treated by the public mental health system in a large U.S. city found the prevalence of homelessness to be 15% over one year, which accords well with estimates in other U.S. urban areas (Folsom et al., 2005). Other subgroups that have been found to experience high rates of homelessness include substance abusers, persons being discharged from jails and prisons, and young adults leaving foster care and other child welfare institutions.

Although reliable national prevalence estimates are difficult to come by, a recent report by a major European nongovernmental organization placed the total number of persons homeless over the course of one year at between 2.7 and 3 million in the countries of the European Union.

Although evidence suggests considerable variation in the prevalence of homelessness among various EU nations, significant differences between countries in the ways in which homelessness is defined and enumerated render precise comparisons impossible (Edgar and Meert, 2005). Nonetheless, analysts believe that the highest current rates of homelessness in Western Europe are in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, where its prevalence is between two and six times greater than rates in neighboring countries (UN-HABITAT, 2000).

While many observers assume that the overall prevalence of homelessness in the United States and the EU nations has increased over the past 25 years, this is difficult to substantiate; apparent increases may be explained in part by the greater public attention that has been focused on the problem. There is also evidence that the prevalence of homelessness may vary significantly with cycles of economic activity.

Duration

The subgroup of persons whose homelessness is of long duration – the so-called ‘chronically homeless’ – tend to arouse the most public concern. This is in part because this group is often the most visible and has been shown to consume an inordinately large share of public health and social welfare expenditures. Nonetheless, research suggests that most homeless episodes are relatively brief and episodic, typically following short-term personal or economic crises, and do not lead to ‘chronic’ or recurrent homelessness in the vast majority of cases.

Sociodemographic Characteristics Of Homeless Persons

Poverty is perhaps the most common shared characteristic of homeless persons since, by definition, homeless persons are typically unable to afford access to housing. Current U.S. data suggest that homeless men outnumber women by roughly two to one and that ethnic minority group members, particularly African-Americans, are overrepresented in the homeless population. Recent immigrants appear to be overrepresented among the homeless population in several European countries, although this does not appear to be the case in the United States.

During the period of the 1960s and 1970s, the typical homeless person was a single, middle-aged male, frequently with a long history of low-paid or seasonal employment. In the United States, this began to change during the early 1980s as more young males and single women joined the ranks of the homeless. During the 1990s and more recently, families (typically a single mother with one or more children) have become the fastest-growing subgroup of the homeless population (Burt, 2001). Homelessness among unaccompanied adolescents and children is also a growing problem. Such young people, who typically have tenuous family connections, are an especially vulnerable group characterized by traumatic life histories and high-risk sexual, health, and substance abuse behaviors.

Causes Of Homelessness

The causes of widespread homelessness reflect a complex interaction between individual and structural factors. An evolving consensus views the overall prevalence of homelessness as determined primarily by structural factors, chief among them being the supply of affordable housing in a particular time and place. The persons who then become homeless in this context, according to this model, are those who are least able to compete for the limited supply of housing due to personal characteristics, sometimes referred to as individual-level risk factors. Some observers use the metaphor of ‘musical chairs’ to describe this process. In this children’s game, a group of players circles a set of chairs to accompanying music. The number of chairs is one less than the number of players. When the music stops, the players scramble for a place to sit, leaving one unfortunate contestant without a seat.

Epidemiologic research has identified a range of individual-level attributes that are associated with an increased likelihood of becoming homeless. These include psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, other medical conditions, lack of social support, and adverse childhood experiences. The specific mechanisms through which these factors may increase the risk of homelessness are complex, since they frequently overlap with each other and with other sociodemographic factors that are associated with homelessness.

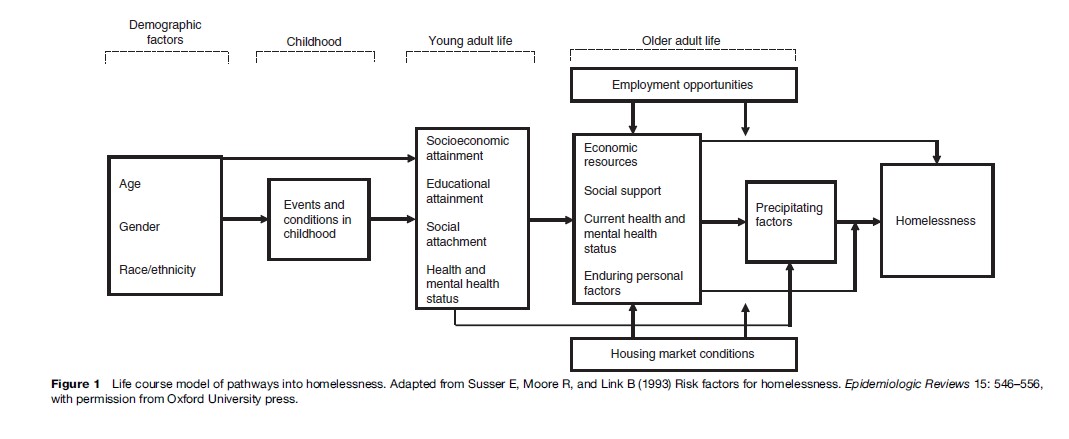

The process of individual homelessness can be understood in a multilevel life course perspective. This perspective views homelessness as the end point of a trajectory in which multiple influences occurring at different points over the life course contribute incrementally to the risk of a person becoming homeless in an environment of scarce housing. For example, demographic characteristics may predispose to social disadvantage, adverse childhood experiences may lead to poor social attachment, inadequate schooling can limit achievement and employment options, housing markets can curtail affordable housing, and the person may experience a traumatic loss, resulting in homelessness (see Figure 1).

Homelessness And Health

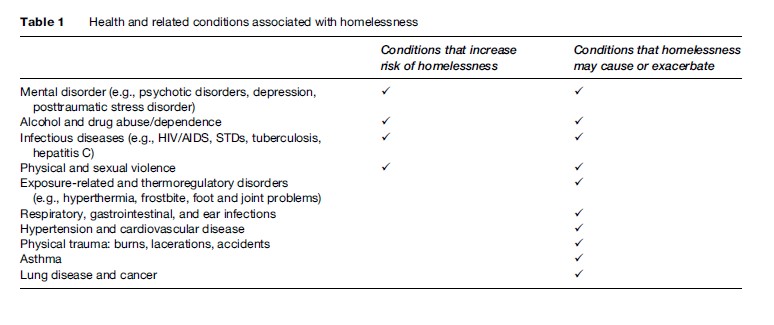

The complicated and reciprocal interplay between homelessness and health is well-documented. While some health conditions operate as risk factors for subsequent homelessness, currently homeless individuals are at elevated risk for adverse health conditions (see Table 1).

Health Conditions Are Risk Factors For Homelessness

Individuals with certain health conditions, including severe mental illness (such as schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders), substance abuse/dependence, and HIV/AIDS, are at higher risk of becoming homeless than are individuals without these conditions.

Persons with severe mental illness are at high risk of becoming homeless for a number of reasons related to their lack of individual resources, inadequate systems of community supports, and the tendency toward social exclusion of mentally ill persons and others with stigmatizing conditions. The move to deinstitutionalization of severely mentally ill persons, coupled with ineffective systems of community care, has left many such individuals without access to needed treatment, social services, and supportive housing. Fragmented treatment systems decrease the availability of continuous care, making it more likely that mentally ill persons will experience psychiatric crises. Furthermore, persons with severe mental illness tend to be poor, due in large part to extremely high rates of unemployment; this places them at a disadvantage in locating and sustaining permanent housing. Those with severe mental illness also tend to experience reduced levels of social support from families and other potential sources of assistance during times of need. The troubling persistence of stigma directed toward mentally ill persons plays a significant role in the reduced opportunities for social and economic involvement experienced by many severely mentally ill persons, particularly in industrialized societies.

As with severe mental illness, individuals with substance abuse problems may also find it difficult to sustain employment, manage their finances, and maintain housing. Substance abuse disorders tend to be chronic, relapsing conditions for which effective interventions are frequently unavailable. Research has also shown that homelessness is considerably more common among persons with HIV/AIDS than among persons without these conditions (Culhane et al., 2001). This heightened risk of homelessness is related to discrimination and the high costs of housing and medical care. HIV/AIDS is also more prevalent among persons with substance abuse and severe mental disorders, further increasing the risk of homelessness in persons with these multiple conditions.

Individuals with comorbid health conditions, such as mental illness plus substance abuse or dependence, are especially vulnerable to becoming homeless. Comorbid conditions also tend to be more long-lasting and severe compared with conditions that are experienced separately.

Homelessness Is A Risk Factor For Disease

Adults

Exposed to numerous deprivations and adverse environmental influences, such as inadequate nutrition, poor hygiene, exposure to the elements, and victimization, homeless adults are at increased risk of developing a broad range of physical health problems. During periods of shelter living, homeless persons typically stay in unclean and overcrowded settings in which infectious diseases are easily transmitted. Furthermore, homeless persons typically live in impoverished communities in which the prevalence of infectious diseases tends to be high.

Joint problems, respiratory infections, and hypertension are common in homeless adults. Foot problems, such as corns, calluses, and immersion foot, are also frequent because of excessive walking and poorly fitting shoes. During cold months, hypothermia and frostbite have been frequently reported. High rates of smoking among homeless adults increase the risk of lung cancer and upper respiratory infections. Chronic diseases most common among homeless adults include hypertension and heart disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, dental problems, and neurological disorders.

Homeless individuals are at high risk for contracting HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (TB). It is estimated that both HIV and TB are between three and five times more prevalent among homeless persons than among housed persons. Furthermore, HIV is a leading cause of death among homeless men and women. Specific risk factors for homeless people for contracting HIV and TB include length and duration of homelessness, number of homeless episodes, injection drug use, and sexual risk behaviors (e.g., sex trading, unprotected sex, multiple partners). The presence of other established risk factors for HIV/ AIDS such as mental health disorders, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and partner violence, are also common among individuals who are homeless. Prevention and treatment measures may also be difficult among homeless populations due to lack of access to health-care services and their unstable life circumstances.

Homelessness is also suspected to be a risk factor for both exacerbating existing mental health and substance abuse problems and for the development of new conditions. An extensive body of research demonstrates that stressful life events are associated with the onset of psychiatric disorders. Exposure to traumatic or otherwise stressful events is common during episodes of homelessness. These include physical or sexual assault and physical trauma such as accidents, burns, and lacerations. Furthermore, there is some evidence that the experience of becoming homeless itself is perceived as a trauma that can lead to mental health and substance abuse problems.

Families With Children

Homeless families (most frequently consisting of a single mother with one or more young children) are a growing segment of the homeless population, particularly in the United States (Burt, 2001). Health needs among homeless mothers include the broad sequelae of physical and sexual violence, which many such individuals report having experienced during both childhood and adulthood. These include posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, depression, and sexually transmitted infections. For homeless women who are pregnant or parenting a newborn, there are typically long delays in obtaining prenatal care and consequent high levels of adverse birth outcomes.

Homeless children are prone to a variety of physical health conditions, including ear infections, gastrointestinal problems, asthma, upper respiratory infections, skin conditions, and poor dentition. These conditions may be related to stress, poor nutrition, and other environmental factors endemic to shelter living. Long-term health consequences of nutritional deprivation, such as delayed growth or iron-deficiency anemia, are also a risk. Lack of basic health services may limit access to required preventive care and vaccination, further increasing the risk of subsequent health problems. Homeless children are also at risk of developing mental health conditions, such as serious behavioral problems, depression, and anxiety, as a result of exposure to multiple stressors associated with homelessness and shelter living. Residential instability can lead to poor academic achievement by homeless children, who are more frequently absent and change schools more often than their nonhomeless peers.

Homeless Youth

Homeless and runaway adolescents are a group with particularly complex health needs. Many come from troubled families where they have experienced early separations, rejection, and abuse. Frequently such youth have lived in out-of-home placements, such as foster homes, residential treatment centers, and juvenile detention facilities. They therefore tend to lack family and social supports as well as fundamental educational, social, and vocational skills required to make an effective transition to independent living as adults. Homeless youth engage in numerous risk behaviors such as injection drug use, unprotected sex, and prostitution, placing them at extremely high risk for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS. Although solid epidemiologic data are lacking, mental health problems, including depression and suicidal behavior, are thought to be particularly common in this population.

Older Adults

Most data indicate that older adults (60 years of age and over) are underrepresented in the homeless population, perhaps as a function of the relatively more robust medical, public welfare, and social service supports typically available to older people, as well as the greater mortality risk associated with homelessness. However, it has been argued that, due to the privations they experience, many middle-aged homeless persons begin to manifest the types of chronic health conditions normally associated with old age. These include cardiovascular disease, cancer, elevated blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. There is also some recent evidence suggesting that, at least in several large urban areas in the United States, the proportion of older persons in the homeless population is increasing, perhaps reflecting the aging of a large cohort of chronically homeless persons who first became undomiciled during the 1980s. This implies that chronic health conditions associated with aging may soon become a more significant problem for health-care providers treating homeless persons.

Homelessness And Mortality

Given the combination of high rates of disease and trauma, exposure to the elements, and poor access to health services, it is not surprising that homeless persons are at significantly higher risk of death than their housed counterparts. Although there is considerable variation in excess mortality between different samples of homeless persons, the age-adjusted risk of death among homeless persons appears to be between two and eight times higher than nonhomeless persons, with greater disparities in death rates found among younger persons (Hwang, 2000). Leading causes of death among homeless individuals include accidents, HIV/AIDS, drug and alcohol overdoses, suicide and homicide, heart disease, and cancer.

Barriers To Health-Care Services

Despite their high levels of health-care need, homeless persons face multiple barriers to accessing routine sources of health, mental health, and substance use services. The need to meet basic survival needs for food and shelter may place health services at a low priority for many homeless persons. Homeless individuals are also typically without the financial resources, health insurance, or transportation needed to gain access to regular health-care services. Some homeless persons may lack insight into their health and mental health needs, or may be hesitant to seek out services because of previous negative experiences, such as rejection or discrimination, in routine health-care settings. Given low access to routine services, homeless individuals are more likely to seek and receive treatment in hospital emergency departments, regardless of whether or not their medical needs are urgent, leading to expensive, fragmented, and often ineffective care. A significant challenge for health service providers is retaining homeless persons in treatment for reasons described above.

Promising service delivery models include specialized programs that integrate components that are intensive, assertive, supportive, rehabilitative, and long-term. Examples of such approaches include mobile street outreach teams, drop-in centers and shelters that provide integrated and intensive referral services, and supportive housing programs that integrate services for health, mental health, and substance use needs. These specialized programs may also provide concrete assistance such as housing, food, clothing, and showers, along with access to health-care. Directly observed therapy, a process in which a health-care provider directly monitors patients’ receipt and use of anti-tuberculosis medications, has also been employed successfully to treat outbreaks of TB in homeless populations (Story et al., 2007).

Preventing Homelessness

Despite growing attention to the problem of widespread homelessness, there has been relatively little progress made toward developing systematic approaches to prevent homelessness. Defining and implementing an effective prevention agenda must be seen as the most important next step in a comprehensive public health response to this vexing problem.

We consider homelessness prevention using the framework of high-risk and population prevention proposed by the epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose (Rose, 1992). High-risk prevention involves identifying persons known to be at especially high risk of homelessness by virtue of individual characteristics or risk factors, and then targeting them for specific interventions. Population prevention, in contrast, promotes prevention strategies aimed at the entire community. This model is especially relevant to homelessness because it draws attention to the need to address prevention not only by direct intervention among those at high risk, but also by modifying the overall social context in which homelessness occurs. Population prevention strategies are a critical adjunct to high-risk prevention approaches, since high-risk strategies, if broadly employed in the absence of population approaches, have the potential to merely redistribute the risk of homelessness to other segments of society, without reducing its overall incidence. Making this distinction is especially important to the prevention of homelessness, given the causal model described above, which sees homelessness as the result of a complex interaction between individual level and structural factors.

High-Risk Prevention

Preventive interventions for high-risk groups typically focus on persons with severe mental disorders, substance abuse problems, and other chronic health conditions. Considerable attention in the United States has recently focused on various models of supportive housing as a prevention strategy for high-risk populations. Although considerable variation exists between specific approaches to such housing, supportive housing programs typically provide permanent housing in the community, generally administered by a social service organization, in combination with on-site health and social services. A growing body of research suggests that such approaches are effective in maintaining formerly homeless persons in housing over extended periods of time. Furthermore, evidence suggests that supportive housing is also cost-effective for chronically homeless people; the expenses associated with providing permanent housing and services is typically less than the public costs of delivering the temporary shelter, emergency health, and police services that would have been used in support of homeless individuals without such housing.

Some controversy exists about whether such accommodations ought to be offered to persons with severe mental disorders and substance abuse problems as an immediate or a subsequent step in their rehabilitation. Proponents of the so-called ‘Housing First’ model believe that even the most severely ill and multiply impaired individuals can be housed immediately in permanent housing without requiring treatment or sobriety as a prerequisite and that such housing will go a long way to reducing their risk of subsequent homelessness (Tsemberis et al., 2004). In contrast, others feel that access to long-term housing ought to be limited to persons who have demonstrated their ‘housing readiness’ by having successfully participated in treatment for these disabilities. There is no clear evidence at this time that one or the other of these competing approaches is necessarily superior.

Another promising prevention approach focuses on efforts to enhance continuity of care for high-risk populations, particularly following institutional discharge and during other transitional periods. Research demonstrates that there is an elevated risk of homelessness in the days and weeks after people leave psychiatric hospitals, correctional facilities, and other institutions. Particularly for those with limited resources and few social supports, these transitions are often associated with discontinuities in care arrangements and increased risk of housing loss. Some observers have identified such transitional periods as critical periods during which a time-limited intervention might effectively reduce the likelihood of homelessness and other adverse outcomes. Such ‘critical time interventions,’ focused on providing concrete assistance while enhancing community support, have been developed and tested with mentally ill persons leaving psychiatric treatment settings, with encouraging results (Herman et al., 2007).

Population-Level Prevention

Although there is to date scant empirical data supporting specific population-level strategies for the prevention of homelessness, the available research suggests that such interventions require a coordinated, multisystem focus on housing, income, and community development initiatives, perhaps targeted toward especially impoverished neighborhoods in which the risk of homelessness is greatest.

With respect to housing, recent public policy in the United States no longer supports the broad development of government-owned low-cost housing, emphasizing the leading role of the private market in housing creation and ownership for the general population. However, given the eroding supply of decent low-cost housing in many parts of the United States, there is growing recognition of the need to increase the supply of housing subsidies in order to assist low-income individuals and families to purchase housing in the private market.

In Europe, analysts have begun to focus on the broad construct of ‘social exclusion’ as a lens through which to understand the growth of homelessness. In this view, recent retrenchment by European states in redistributive activities, particularly in the area of facilitating access to housing for economically vulnerable groups, has contributed to homelessness, poverty, and other forms of exclusion among the poor and disadvantaged. This analysis suggests the need for a ‘rights-based’ approach, in which governments would be held accountable for ensuring a sufficient supply of decent, affordable housing as a fundamental human right. Only through such a universal approach, it is argued, will it be possible to develop truly effective comprehensive prevention strategies (Edgar et al., 2002).

Prevention Challenges

Significant challenges must be overcome before prevention strategies can be broadly implemented. One is the problem of effective targeting – how to ensure that prevention activities will be directed toward those individuals who are indeed at high risk of becoming homeless. Most prevention approaches that have been attempted so far have not been carefully targeted, making it difficult to assess their effectiveness or efficiency. Furthermore, research efforts to date that have employed statistical methods aiming to identify subgroups of poor individuals who are most likely to become homeless have not been especially successful. Even if effective targeting could be accomplished, intensive interventions directed at specific high-risk groups may redistribute rather than reduce homelessness. For instance, a clinical trial may demonstrate that persons with mental illness who receive an intervention are more likely to retain housing than those who do not, but this may not have reduced the overall amount of homelessness in the population in which the intervention occurs. Those receiving the intervention may simply have gained access to resources that were consequently denied to others.

Conclusion

It is unacceptable that pervasive homelessness should continue to plague affluent societies across the world. This phenomenon, and its attendant conditions, is symptomatic of a growing trend toward resource disparities in the United States and other parts of the industrialized world. From a public health perspective, it is abundantly clear that homelessness inordinately affects those with multiple health and social vulnerabilities, and that homelessness itself contributes to the onset and exacerbation of a variety of serious health conditions. To eradicate widespread homelessness will require a sustained commitment by governments, private organizations, and individuals using a broad variety of approaches. While effective primary prevention is clearly a desirable long-term goal, immediate efforts are required to provide temporary and permanent housing coupled with a range of interventions to address the immediate health concerns of this underserved and needy population.

Bibliography:

- Burt MR (2001) Helping America’s Homeless: Emergency Shelter or Affordable Housing? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

- Culhane DP, Gollub E, Kuhn R, and Shpaner M (2001) The co-occurrence of AIDS and homelessness: Results from the integration of administrative databases for AIDS surveillance and public shelter utilization in Philadelphia. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 55(7): 515–520.

- Edgar B, Doherty J, and Meert H (2002) Access to Housing: Homelessness and Vulnerability in Europe. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Edgar B and Meert H (2005) Fourth Review of Statistics on Homelessness in Europe. Brussels, Belgium: European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless.

- Edgar B, Meert H, and Doherty J (2004) Third Review of Statistics on Homelessness in Europe: Developing an Operational Definition of Homelessness. Brussels, Belgium: European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless.

- Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al. (2005) Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10 340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. American Journal of Psychiatry 162: 370–376.

- Herman D, Conover S, Felix A, Nakagawa A, and Mills D (2007) Critical time intervention: An empirically supported model for preventing homelessness in high risk groups. Journal of Primary Prevention 28: 3–4.

- Hwang SW (2000) Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. Journal of the American Medical Association 283(16): 2152–2157.

- Rose G (1992) The Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Story A, Murad S, Roberts W, Verheyen M, and Hayward AC (2007) Tuberculosis in London: The importance of homelessness, problem drug use and prison. Thorax 62: 667–671.

- Susser E, Moore R, Link, et al. (1993) Risk factors for homelessness. American Journal of Epidemiology 15(2): 546–556.

- Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, and Nakae M (2004) Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health 94(4): 651–656.

- UN-HABITAT (2000) Strategies to Combat Homelessness. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Centre for Human Settlements.

- Baumohl J (1996) Homelessness in America. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

- Edgar B, Doherty J, and Meert H (2004) Immigration and Homelessness in Europe. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Hopper K (2003) Reckoning with Homelessness. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kozol J (2006) Rachel and Her Children: Homeless Families in America. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- Levinson D (2004) Encyclopedia of Homelessness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- O’Connell J (2004) The Health Care of Homeless Persons: A Manual of Communicable Diseases and Common Problems in Shelters and on the Streets. Boston, MA: Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.