This sample Relief Operations Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Background

Relief operations refer to the humanitarian aid or assistance given to people in distress by individuals, organizations, or governments with the core purpose of preventing and alleviating human suffering.

The principles of humanitarian intervention are impartiality, neutrality, and independence. Impartiality means no discrimination on the basis of nationality, race, religious beliefs, class, gender, or political opinions: humanitarian interventions are guided by needs. Neutrality demands that humanitarian agencies do not take sides in either hostilities or ideological controversy. Independence requires that humanitarian agencies retain their autonomy of action. These principles, originally drawn up for war and consolidated in humanitarian law expressed in the Geneva Convention of 1949, underlie response to conflict-related and natural disasters.

Since the early 1990s, there has been both an increase in the number of disasters and a change in the nature of emergencies, thus leading to a substantial increase in relief operations. Natural disasters have grown in number largely due to increased climate variability. Complex emergencies (situations of armed conflict) have increased, particularly since the end of the Cold War, and are now characterized by high levels of civilian casualties, deliberate destruction of livelihoods and welfare systems, collapse of the rule of law, and large numbers of displaced people. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), there were 8.4 million refugees and 23.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) as of December 2005.

Emergencies have changed in nature from predominantly natural disasters, dominated by flood and drought, to complex emergencies and technological disasters. The ‘War on Terror’ following events on 11 September 2001 and the subsequent interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq have created new challenges for the implementation of relief operations.

The increasing frequency and changing face of emergencies have caused humanitarian expenditures to soar. Total humanitarian assistance reached an all-time high in 2005 at around US$18 billion – the Asian tsunami alone mobilized an unprecedented response. In real terms, humanitarian aid from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members rose by 32% in 2005. (DAC is a forum of major bilateral donors with 23 members, including the Commission of the European

Communities and the United States.) These figures do not account for charitable donations from individuals or groups, such as churches, and they do not capture non-Western assistance such as that provided by Islamic entities.

The international humanitarian system consists, principally, of four sets of actors: donor governments, including the European Commission Humanitarian Office (ECHO), the United Nations (UN), the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs). Local NGOs and beneficiaries have little voice in the system.

A broad division of labor exists within the United Nations system. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA) is in charge of the policy and planning framework; World Food Program (WFP) is responsible for emergency food delivery; the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) is in charge of emergency shelter; United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) is responsible for nutrition and water and sanitation; and the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) is responsible for emergency agriculture, which if successful should mark the end of the emergency and the diminution of the role of the WFP.

Ironically, the health sector is the only sector not delivered directly by the UN. That rests largely with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Me´decins Sans Frontie`res (MSF), who arguably are the only two absolute humanitarian organizations. The World Health Organization (WHO) is generally involved with programming and policy, less involved with the management of medical delivery, and not at all involved in medical delivery. Despite this there are three distinct areas in which the UN delivers what can broadly be described as medical interventions. These are food security (including nutrition), shelter, and water and sanitation.

On-the-ground management of relief remains a contentious subject and is closely tied to the issue of coordination. The United Nations system, through OCHA, is usually responsible for the coordination of ground-level management, increasingly through the ‘Cluster Approach’ in which agencies are identified to lead coordination in a specific sector. In places where the United Nations is not acceptable, the ICRC plays the critical coordination role. Most disaster appeals are underfunded so the humanitarian system usually has insufficient resources to deliver the appropriate humanitarian response. As a result, most NGOs agree to be coordinated through the UN system. When disaster appeals are met or exceeded, as in the Asian Tsunami, the different United Nations agencies and international NGOs tend to work more independently. Coherent and effective on-the-ground management relies ultimately on the honest sharing of information about beneficiary need and coverage. FAO has provided a model of good practice for this by chairing information sharing through its food security assessment unit (FSAU). In general, however, information sharing for on-the-ground management, and therefore effective coordination, remains the weakest link in humanitarian delivery.

Health

Everyone has the right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health and everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of themselves and their family, including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and social services.

Disasters usually generate significant impacts on the public health and well-being of affected populations. These impacts can be described as direct (e.g., death, injury, or psychological trauma) or indirect (e.g., increased rates of infectious disease, malnutrition, complications of chronic disease).

The severity of direct and indirect health impacts and the subsequent need and type of relief operations depend upon several factors. First, the type of emergency or disaster situation: different types of disaster are associated with differing scales and patterns of mortality and morbidity. The public health and medical needs of an affected community will therefore vary according to the type and extent of disaster. Earthquakes, for example, cause many injuries requiring medical care, whereas floods cause relatively few. These again differ significantly from injuries of victims of armed conflict. In general, public health interventions and humanitarian assistance are designed to ensure the greatest health benefits provided to the greatest number of people.

Second, the ability of existing services and resources of a country to cope greatly determine the level and type of health humanitarian assistance required. Natural disasters can cause serious damage to health facilities, water supply, and sewage systems, having a direct impact on the health of the population dependent on these services. The earthquake that struck Mexico City in 1985, for example, resulted in the collapse of 13 hospitals. In just three of those buildings, 866 people died, 100 of whom were health personnel. As a result of Hurricane Mitch in 1998, the water supply systems of 23 hospitals in Honduras were damaged or destroyed, and 123 health centers were affected.

Existing health services in most developing countries are already inadequate or unable to cope with current demands, therefore automatically exacerbating the need for health humanitarian aid when an emergency strikes. In complex emergencies, health infrastructure, services, and the staff themselves can be targeted and destroyed. In addition, inadequate food supplies, damaged water and sanitation facilities, lack of shelter, and overcrowding can have the indirect impact of increasing rates of infectious diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and measles.

Third, the current health status of the population can affect the severity of direct and indirect health impacts and the need for humanitarian assistance. Populations already suffering a lack of health services, food shortages, and poor water and sanitation facilities will be inherently weak. These populations are extremely vulnerable to external shocks, and should a disaster occur, injuries are likely to be more severe, casualties higher, and the need for humanitarian assistance greater. Chronic development conditions are the driver for many acute emergencies.

Health humanitarian assistance is delivered largely by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Me´decins Sans Frontie`res (MSF). Both ICRC and MSF have an extensive range of guidelines they use and follow when implementing relief operations. ICRC, the UN, and most NGOs accept the Sphere Standards in the delivery of humanitarian aid, although most individual organizations have separate implementation instructions. (The Sphere Standards are the most widely acknowledged international standards. The Sphere Standards detail minimum standards for disaster response and have been ratified by the majority of humanitarian organizations. Over 400 organizations representing 80 countries have participated in various aspects of the Sphere Project.) The Sphere Project was launched in 1997 by a group of humanitarian NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Sphere is based on two core beliefs: first, that all possible steps should be taken to alleviate human suffering arising from calamity and conflict, and second, that those affected by disaster have a right to life with dignity and therefore a right to assistance. MSF assisted with the establishment of the technical standards and key indicators of the Sphere Handbook but prefer to use their own technical standards, which strongly acknowledge the conditionality of intervention by individual disaster. The Sphere Handbook contains several chapters detailing the minimum standards of health, food, shelter, and water and sanitation that must be achieved when delivering humanitarian aid. MSF usually use Sphere Standards and indicators as a starting point in collaboration with their own ‘Clinical Guidelines.’

There exists an extensive range of Sphere Standards and indicators relating to health systems and infrastructure, control of communicable diseases, and control of no communicable diseases. These standards and indicators can be achieved most efficiently when the disaster-affected population is involved in the design, implementation, and monitoring of health services. Relief operations should identify and build on existing local capacities if a speedy and sustainable recovery from the disaster is to be achieved. In most disaster situations, women and children are the main users of health-care services and, therefore, it is important to seek both men’s and women’s views to ensure that services are equitable, appropriate, and accessible to those most in need.

Food

Minimum dietary energy requirements are the amount of dietary energy per person that is considered adequate to meet the energy needs for light activity and good health. This requirement is expressed as kilocalories per day. On average, a healthy adult requires approximately 2070 kilocalories per day. This varies depending on age, sex, lifestyle, daily level of activity, height, weight, body composition, and current medical status.

It is a human right to have adequate food and be free of hunger. In 2005, the United Nations World Food Program supplied 73.1 million people with food aid. The number of food emergencies has been rising over the past two decades, from an average of 15 per year during the 1980s to more than 30 per year since the turn of the millennium.

States and nonstate actors have responsibilities to fulfill the right to food. There are many situations in which these state and military obligations, however, are violated; for example, the deliberate starvation of populations or the destruction of their livelihoods as a war strategy. In these situations, humanitarian actors must aid the populations affected through providing food assistance via methods that respect national law while meeting international human rights obligations.

Natural disasters such as floods, land-slides, or mudslides and volcanic eruptions can severely affect food availability. Standing crops can be completely destroyed, and seed stores along with family food stocks can be totally lost. Depending upon the severity of these disasters, a great need for food aid can be generated.

Access to food and the maintenance of adequate nutritional status are critical determinants of people’s survival in an emergency situation. During the first days after a disaster, the extent of damage is often unknown, and communications are difficult. As an immediate relief step, available food should be distributed in sufficient quantity to ensure survival. No detailed calculations need be made of the precise vitamin, mineral, or protein content in the food distributed in the initial phase, but supplies should be acceptable, palatable, and provide sufficient energy. During this stage of the emergency it is simply important to provide a minimum of 6.7 to 8.4 megajoules (1600 to 2000 kcal) per person per day.

As soon as possible after the disaster or emergency situation has occurred, an initial assessment and analysis is needed to determine people’s own food and income sources and identify any threats to these sources. This needs assessment should identify the quantity and type of food aid necessary to ensure people are able to maintain an adequate nutritional status. If food aid is required, an appropriate general ration must be established.

If there is a failure in the general food pipeline or if acute food insecurity or malnutrition is already present, a general food ration can prove insufficient or inappropriate. Moderate malnutrition can be addressed through improving the general food ration, ensuring food security, and establishing access to health care, sanitation facilities, and potable water. Enhancing the general food ration by ‘targeted supplementary feeding’ is usually the primary strategy for correction of moderate malnutrition and prevention of severe malnutrition. When rates of malnutrition are high, targeting the moderately malnourished can be inefficient and therefore all individuals meeting certain at-risk criteria (e.g., pregnant women and those aged 6–59 months) become eligible for supplementary feeding. This is known as blanket supplementary feeding.

Severe malnutrition is corrected through therapeutic care. This can be delivered as 24-hour in-patient care, day care, and home-based care. The provision of in-patient care depends on other standards, such as the provision of functioning water and sanitation facilities.

At the onset of an emergency, screening (a one-time rapid assessment) can be used to identify immediate needs and individuals likely to be most at risk. Nutritional surveillance should be initiated soon after, if not immediately (depending on staff and resources available), to identify the nutritional status of the population and provide warning of any impending crisis. The World Health Organization (2006) has developed a series of child growth standards using a range of measurements to provide guidelines for identifying the healthy growth of children. Mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) and body mass index (BMI, also referred to as weight for height) are measurements generally taken from children to assess and identify levels of malnutrition. MUAC is a measure of thinness or wasting from the left mid-upper arm. It is only sensitive in children 1–5 years. A MUAC measure of more than 135 mm is normal, and children with an MUAC less than 135 mm are measured using their weight/height ratio to see whether they should enter the malnutrition program. The weight/height ratio is considered the most reliable indicator in emergencies of the nutritional status of a child. A MUAC of 110–124 mm illustrates moderate malnutrition and less than 110 mm demonstrates severe malnutrition. When measuring MUAC, colored bands are used to help illiterate workers classify children’s nutritional status. BMI is an index of weight for height (BMI = weight (kilograms)/height (meters squared)), which can identify moderate and acute malnutrition as a measure of wasting. According to the WHO Global Database on Body Mass Index (WHO, 2006), the normal range is 18.50–24.99; moderate thinness is 16–16.99; severe thinness is less than 16; and underweight is 18.5.

Blanket feeding can be used at the start of an emergency, as implementation of a full general food distribution program takes time. Blanket feeding can also be initiated when there is a severe food crisis or when a significant and persistent deterioration in food availability is expected even when nutritional problems have not yet arisen. Supplementary feeding is usually necessary in a food crisis or famine situation in which malnutrition rates exceed 15%. A therapeutic feeding center (TFC) should be established when the absolute number suffering severe malnutrition exceeds 30 patients and the prevalence of severe malnutrition is above 3%, providing that staff and other resources are available. When the numbers are smaller, it is more appropriate to support existing health structures in the provision of therapeutic feeding care rather than implementing a new program.

The Sphere Handbook (Sphere Project, 2004) outlines the standards that food aid should meet, according to various levels of need and the severity of the situation. It includes standards and indicators for general nutritional support, moderate malnutrition, and severe malnutrition. There are also standards for the correction of micronutrient deficiencies, but these largely rely on the achievement of standards in health systems and infrastructure and the control of communicable diseases.

The decision to distribute large amounts of food aid, although made at the political level, should be based on the most accurate information available. If unnecessarily large quantities of food are brought into an area, recovery can be hindered. Excess food aid can flood the market, depressing prices, and as a result render the crops that were harvestable worthless. This can have serious effects on livelihoods. Farmers unable to make a profit will have insufficient funds to purchase the seeds, tools, or livestock necessary for the next harvest. Thus, more developmental aid would be necessary in the form of seeds and tools to restart the local economy and prevent a dependence on relief from emerging.

Food distribution centers and hospitals treating malnutrition often become quickly overcrowded in times of humanitarian crisis. People camp near them to ensure that they have a secure source of food and medical treatment, especially in rural areas in which villages are sparsely populated and the nearest food distribution center can be several miles away. This can cause severe health impacts as disease is able to spread quickly in overcrowded areas with already weakened populations. If coupled with poor water and sanitation facilities, the situation can soon become catastrophic. In 1994, for example, approximately 1 000 000 Rwandans fled the conflict and genocide and crossed the border into Zaire, exhausted, hungry, and scared. The small town of Goma was overrun with refugees, who were forced to relocate 25 miles from the nearest water source. The average available water was evaluated at 200 mm3 per person per day. The initial camp was built on a lava bed, making latrine building almost impossible. Within the first week of arriving, almost 50 000 refugees died as epidemics of cholera and Shigella dysenteriae swept through the camps. This devastating cholera outbreak was a result of inadequate clean water, poor sanitation, a lack of hygiene, the level of health, and the promiscuity among the refugees.

In 1999, Andre Briend, a French scientist, developed ‘Plumpy’nut,’ a peanut-based food for use in famine relief. It is a ready-to-use therapeutic food in a foil pouch, which contains 500 kcal and weighs only 92 g. Plumpy’nut was first used on a large-scale during 2005 for the crisis in Darfur (initially feeding 30 000 children), western Sudan. It has since been used in Ethiopia, Congo, Malawi, and Niger, and according to aid agencies is cutting malnutrition by half.

Plumpy’nut can be administered to meet varying levels of need, for example, four sachets of Plumpy’nut per person per day for severe malnutrition and one sachet per person per day with supplementary foods to treat moderate malnutrition. Once opened, Plumpy’nut has a shelf life of two years, which is advantageous in locations where refrigeration or storage is a problem. Plumpy’nut also allows parents to care for their own children at home as opposed to in crowded hospitals. This both frees up much needed hospital space and returns responsibility and control to the parents. The major advantage of Plumpy’nut is that unlike powered milk given to malnourished children, no water or any preparation is necessary, which is important in areas in which water supplies may be disrupted, scarce, contaminated, or unsafe. Current projects are under development in Malawi and Niger to begin producing Plumpy’nut locally, which is essential to reducing costs and building the capacity and resilience of affected populations.

Shelter

Hypothermia is a decrease in body temperature to 94 F or lower. At low temperatures the body’s organs become less effective and slow down. If body temperature falls below 86 F, organs are likely to stop working and death is probable. Hyperthermia is an increase in body temperature above 99 F. When a person’s surroundings are hotter than his or her body temperature, heat cramps, heat exhaustion, or heatstroke can occur. Both hypothermia and hyperthermia are preventable. Key aspects of avoiding hypothermia include maintaining a warm environment, wearing several layers of clothes, and eating warm food and fluids. Hyperthermia can be avoided through wearing light clothes that allow air and moisture to pass through easily, replacing fluids and salts lost through sweating, and using air-conditioning or fans.

On 8 October 2005, an earthquake hit South Asia, mostly affecting northern Pakistan. Approximately 73 000 people were killed, over 100 000 people were injured, and 3.3 million people were homeless and in need of shelter as hundreds of thousands of buildings collapsed. On October 13, the snows started to fall as the harsh Himalayan winter set in. The UN declared that 210 000 tents and 2 million sleeping bags were needed immediately to stop people from dying of the cold; 74% of the 250 000 tents rushed to the earthquake zone in the aftermath of the quake were unsuitable for the winter conditions. As a result most NGOs and INGOs spent their time ‘winterizing’ the tents and providing materials to build sturdier shelters. Furthermore, only a handful of the camps that were established met the Sphere Standards, and sanitation was becoming a major problem. Cold-related injuries, such as pneumonia, soared as temperatures fell and a number of people, mainly children, died as a result.

Shelter, and most importantly appropriate shelter, is a crucial element of humanitarian assistance and a critical determinant for survival in the initial stages of a disaster. The most basic response to the need for shelter is the provision of clothing, blankets, and bedding that maintain health, privacy, and dignity; that is, delivery at a personal level before the delivery of buildings. Beyond survival, shelter is necessary to provide security and personal safety, protection from the climate, and enhanced resistance to ill health and disease. People also require basic goods and supplies to meet their personal hygiene needs, to prepare and eat food, and to provide necessary levels of thermal comfort. The type of aid required to meet these needs is determined by the nature and scale of the disaster, the climatic conditions, local environment, political and security conditions, and the ability of the community to cope.

According to the Sphere Standards, the priority is encouraging affected households to return to the site of their original dwelling when possible, or if this is not possible, the affected populations should settle independently within a host community or with host families. When these options are not possible, affected households should be accommodated in large shelters or temporary camps, also referred to as ‘transitional settlements’ (the transitional settlement approach emerged in response to recent emergencies bringing together postdisaster and postconflict capacities, such as after the Asian Tsunami of 2004). The physical planning of these shelters or settlements must use local planning practices when possible and must be able to provide suitable privacy, safe access to water, sanitary facilities, health care, and solid-waste disposal. For longer-term shelters, graveyards, schools, places of worship, meeting points, and recreational areas must be considered. The design of the shelter and materials used should be familiar to the affected population when possible and provide sufficient thermal comfort, fresh air, and protection from the climate.

The health, water, and sanitation sectors are well supported by a body of support tools, but other than the Sphere Standards, none of the few texts available that provide codes and standards offer information specific to shelter and housing programs; subsequently, settlement, shelter, and housing programs remain weak in planning and coordination, both internally and in linking to other sectors. Recent initiatives to address this lack of guidance and information, include the following:

- The Shelter Meeting, held biannually in Geneva since 2004. This meeting is the sector forum for postdisaster and postconflict transitional settlement, shelter, and reconstruction. The forum enables humanitarian organizations to discuss, coordinate, review, and agree on policy, good practice, and technical specifications.

- The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (ISAC) Cluster Initiative is under development by UN bodies, international organizations, and INGOs.

Three of the nine clusters proposed to coordinate humanitarian response describe the shelter sector:

- Emergency Shelter, chaired by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (for conflict-generated displaced people) and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (for natural disasters);

- Early Recovery, chaired by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP); and

- Camp Coordination and Camp Management, chaired by UNHCR (for conflict-generated displaced people) and by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) (for natural disasters).

Water And Sanitation

A human being on average can survive on 5 l of water per day. Basic needs, however, go beyond what we need to drink or ingest through our food for daily survival. It is estimated that one person requires 15 l per day to maintain a basic standard of personal and domestic hygiene sufficient to maintain health.

Clean water is a basic requirement for life and health. Sufficient and safe water is necessary to prevent death from dehydration, reduce the risk of water-related disease, and provide for consumption, cooking, and personal and domestic hygienic requirements. Sanitation has proven equally critical in preventing ill health and is also recognized as a basic human right.

The need for safe water and sanitation becomes elevated in the initial stages of a disaster when people are more vulnerable as a result of injuries, malnourishment, and stress, and diseases are able to spread easily through overcrowding and contaminated water supplies. Preventable diseases such as diarrhea kill more people in chronic emergencies than any other factor, including conflict.

From 1993 to 2006, 6.5 million people received emergency water and sanitation (WATSAN) aid. The Sphere Handbook details the minimum requirements for this aid, which include standards and indicators regarding water quality, supply, use, and sanitation facilities.

Simply providing sufficient water and sanitation facilities, however, will not ensure optimal use or impact on public health unless coupled with hygiene promotion. The affected population must possess the necessary information, knowledge, and understanding regarding water and sanitation-related diseases. This relies on information exchange between the aid agency and affected community in order to identify the key hygiene problems, existing awareness, and required knowledge to ensure optimal use of water and sanitation facilities. This information enables the design, implementation, and monitoring of water and sanitation aid to have the greatest impact on public health. The Sphere Standards recognize the importance of hygiene promotion and incorporate appropriate standards to ensure that hygiene-promotion messages and activities address key behaviors and any misconceptions.

Water, sanitation, and hygiene promotion aid must be designed and implemented in consultation with the affected populations. This is necessary to ensure that the key hygiene risks of public health importance are identified. The involvement of both men and women is also needed to ensure equitable access to the resources provided. In most disaster situations, the responsibility for collecting water falls to women and children. When using communal water and sanitation facilities, women and adolescent girls can be vulnerable to sexual violence or exploitation. An equitable participation of men and women in planning, decision making, and local management will help minimize these risks and ensure that the affected population has safe and easy access to water and sanitation facilities.

Initially the delivery of water and sanitation aid was dominated by the provision of clean water, whereas sanitation facilities were often inadequate if not totally absent. Politicians, decision makers, and donors did not consider sanitation to be of equal importance to water supply. They failed to recognize, for example, that while investments in water quality and quantity could reduce deaths from diarrhea by 17%, sanitation could reduce these by 36% and hygiene promotion by 33%. In recent years, however, research and an expanse of literature and information available have ensured that the importance of sanitation has become more internationally recognized:

- In 2002 sanitation was recognized as a basic human right.

- The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000) include a target to halve by 2015 the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

- The Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) (1990) was established, which has a special interest in sanitation and hygiene and emphasizes the need to view water, sanitation, and hygiene as inseparable. (WSSCC exists under a mandate from the United Nations and is governed by a multistakeholder steering committee. It focuses exclusively on people around the world who lack water and sanitation.)

- The internationally used Sphere Handbook (2004) has a specific chapter detailing standards for water supply, sanitation, and hygiene promotion.

Sanitation is becoming recognized as an essential element of humanitarian assistance that is equally important as supplying clean water, food, and medical care in ensuring the health of populations. Furthermore, these international initiatives, together with an increase in research and publications, have highlighted that water and sanitation must come hand in hand with hygiene promotion to ensure the optimal use of humanitarian aid.

Funding

Health, food, shelter, water, and sanitation are intricately linked and dependent upon one another, and they must all be delivered in a humanitarian emergency to ensure the survival of the affected population. The successful implementation of the various sectors of humanitarian aid depend upon the levels of funding received. The consolidated appeals process (CAP) was established in 1991 and facilitated by OCHA with the aim to raise funding and assist organizations in planning, implementing, and monitoring their activities in crisis regions. The CAP has since become the humanitarian sector’s main tool for coordination, strategic planning, and programming.

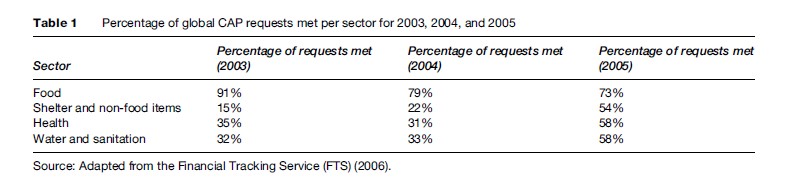

On average the CAP has sought US$3.1 billion per year and received US$2.1 billion per year (68%). Because 100% of the appeals have not been met, several sectors or appeals have remained underfunded. Table 1 illustrates the percentage of CAP requests fulfilled per sector.

As Table 1 indicates, there is a tendency for food aid appeals to be met through the CAP more often than, for example, water and sanitation, which has almost always received under half of its appeals. The links between these sectors are clear, and the repercussions of insufficient humanitarian aid in one will detrimentally affect the others.

In response, the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), a United Nations relief fund, was officially launched in March 2006. The objective of the CERF is to provide urgent and effective humanitarian aid to regions threatened by, or experiencing, a humanitarian crisis. The CERF was adopted in December 2005 and upgrades the loan mechanism under the 1992 Central Emergency Revolving Fund from US$50 million to approximately US$450 million. The CERF is administered under the Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator in consultation with humanitarian agencies. The CERF is not meant to detract from voluntary contributions to humanitarian programs, or to replace the consolidated appeals process or additional funding channels. Rather, it is meant to mitigate the unevenness and delays of the voluntary contribution and provide funding to undersupported operations.

Vulnerable Groups

There are a number of vulnerable groups in humanitarian emergencies that usually require special attention and must be considered in all aspects of relief operations. The disabled, elderly, and children are immediately identifiable groups that have special needs such as particular dietary requirements or medical attention. Other vulnerable groups can prove more difficult to identify, and their needs and effects upon emergencies appear less apparent; for example, people living with HIV/AIDS and internally displaced persons (IDPs).

HIV/AIDS

In 2003, 3 million people died of HIV/AIDS, and the pandemic is turning into a large-scale chronic disaster. Rehabilitating agriculture generally marks the end of emergency aid and a return to development, but the advancing HIV/AIDS epidemic has produced ‘new variant famine’ in which the lack of labor retards that transition and creates food insecurity.

People living with HIV/AIDS need a nutritious, well-balanced diet. Poor nutrition can reduce medication efficacy and adherence and can accelerate the progression of the disease. A recent USAID study found that, compared to an average adult, people living with HIV/AIDS require 10 to 15% more energy and 50 to 100% more protein per day. HIV damages the immune system, which reduces appetite and the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. As a result, the person becomes malnourished, loses weight, and is weakened. One possible sign of the onset of clinical AIDS is a weight loss of about 6–7 kg for an adult. Should a person already be underweight, this further weight loss would be extremely damaging.

The spread of HIV/AIDS is also of concern in complex emergencies. The risk of HIV infection is exacerbated by the high incidence of sexual violence and sexual exploitation in conflict situations. Humanitarian interventions must recognize the importance of providing aid appropriate to, and that protects the rights of, people living with HIV/AIDS. Consequently, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (ISAC; ISAC is a forum involving key UN and non-UN humanitarian partners) has produced ‘‘Guidelines for HIV/AIDS Interventions in Emergency Settings’’ (revised 2003), which aims to integrate HIV/AIDS components into all relevant programming areas.

Internally Displaced Persons

IDPs are people who have been forced from their homes but have not crossed international borders, as a result of, or in order to avoid, the effects of armed conflict or situations of generalized violence. The legal position of IDPs in terms of existing human rights and humanitarian law was established in the United Nations ‘‘Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement’’ (1998). Unlike refugees, whose movement across national borders provides them with special status in international law with rights specific to their situation, IDPs have no such entitlement. Humanitarian assistance is thus limited, in principle, to supportive actions undertaken with the consent of the country in question. When governments are unable or unwilling, however, to provide protection to IDPs, humanitarian organizations have sought to assist these groups, grounding their right to provide assistance on existing provisions of international humanitarian law to war victims and on human rights treaties.

Identification of IDPs, the different groups of displaced persons, and the varying needs of these groups are all further issues in the delivery of humanitarian assistance. IDP groups can mix among resident communities, gather in camps, disperse throughout a territory, or be mixed with combatants who divert relief supplies and create serious security problems. A special category of IDPs that generates extreme concern to the humanitarian community is demobilized soldiers, as their displacement is not only from their homes but also their livelihoods. Under these circumstances, trauma, mental health, and psychological health problems often occur. Humanitarian organizations must address all these issues while upholding the principles of impartiality, neutrality, and independence if humanitarian aid in all sectors is to prove adequate, appropriate, and effective.

Conclusion

Humanitarian interventions attempt to meet the most basic needs of the population: food, water, shelter, and health care. These sectors are all interrelated and the standards achieved in one influence and can even determine progress in another. For humanitarian assistance to prove effective, coordination and collaboration are needed throughout these sectors.

Despite progress, there are still well-known problematic areas in the delivery of relief operations, especially over coordination of interventions and connectedness to development activities once the emergency period has passed. There remains a lack of attention to preparedness and predisaster planning in general, and there is limited attention to indigenous coping strategies. Targeting of humanitarian assistance, particularly around issues of gender, remains problematic. It seems that these problems are somewhat intractable because ultimately no one has responsibility for the management of humanitarian assistance and since essentially it is seen to be doing good.

Bibliography:

- The Sphere Project (2004) Sphere Handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: The Sphere Project.

- WHO (2006) Global Database on Body Mass Index. http://www.who. int/bmi/index.jsp (accessed October 2007).

- De Jong D (2003) Advocacy for Water, Environmental Sanitation and Hygiene. Thematic Overview Paper. Delft, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- Deng F (1998) Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. New York: United Nations.

- Development Initiatives (2005) Global Humanitarian Assistance Update 2004–2005. London: Development Initiatives.

- Development Initiatives (2006) Global Humanitarian Assistance 2006. London: Development Initiatives.

- FAO (2002) Living Well with HIV/AIDS. A Manual on Nutritional Care and Support for People Living with HIV/AIDS. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Financial Tracking Service (FTS) (2006) The Global Humanitarian Aid Database. http://ocha.unog.ch/fts/globsum.asp?FTS (accessed October 2007).

- Fisher J (2006) For Her. Evidence Report. Geneva, Switzerland: Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC).

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) (2000) The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2000. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Goma Epidemiology Group (1995) Public health impact of Rwandan refugee crisis: What happened in Goma, Zaire, in July, 1994? The Lancet 345: 339–343.

- Humanitarian Practice Network (HPN) (2003) Me´decins Sans Frontie`res Benchmarks for Health Programming. London: ODI HPN.

- ICRC (2006) ICRC publications – assistance. http://www.icrc.org/Web/ eng/siteeng0.nsf/htmlall/section_publications_assistance (accessed October 2007).

- Me´ decins Sans Frontie` res (2006) Clinical Guidelines. Diagnosis and Treatment Manual, 7th edn. Paris, France: MSF.

- Nutriset (2006) Products for Emergencies. http://www.nutriset.fr/ products/en/malnut/plumpy.php: nutrisetnutriset (accessed October 2007).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (1996) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). New York: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Office for the High Commission for Human Rights (2002) The International Bill of Rights. http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu6/2/fs2. htm (accessed October 2007).

- Oxfam (2006) Pakistan Earthquake: 100 Days after. Press Release 16 January 2006. Oxford, UK: Oxfam.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (2000) Natural Disasters: Protecting the Public’s Health. Washington, D.C.: PAHO and WHO.

- Shelter Centre (2006) Shelter: Summary of Transitional Settlement. www.sheltercentre.org (accessed October 2007).

- UNAIDS (2004) Report on the Global AIDS epidemic. Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNHCR and World Food Programme (WFP) (1999) UNHCR/WFP Guidelines for Selective Feeding Programmes in Emergency Situations. Rome, Italy: UNHCR and WFP.

- United Nations (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948–1999. General Assembly Resolution on 217 A (III). http://www. un.org/Overview/rights.html (accessed October 2007).

- United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) (2006) What Is the CERF? http://ochaonline2.un.org/Default.aspx?tabid=7480 (accessed October 2007).

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2000) Handbook for Emergencies. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR.

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2006) 2005 Global Refugee Trends. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR.

- USAID (2003) HIV/AIDS. http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/aids/TechAreas/nutrition/nutrfactsheet.htmlUSAID (accessed October 2007).

- USAID, Food Nutrition Technical Assistance (2001) HIV/AIDS: A Guide for Nutrition Care and Support. Washington, D.C.: USAID.

- Waal A and Tumushabe J (2003) HIV/AIDS and Food Security in Africa. A Report for the Department for International Development (DfID). Pretoria South Africa: DfID.

- World Food Programme (WFP) (2006) Fast Food: WFP’s Emergency Response. http://www.wfp.org/ (accessed October 2007).

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2003) The Right to Water. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2006) Global Database on Body Mass Index. http://www.who.int/bmi/index.jsp (accessed October 2007).

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.