This sample Trends in Human Fertility Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

The number of children born per woman and the timing of births are directly relevant to public health and health services in many ways. The level of childbearing, for instance, determines the demand for obstetric and child health services and has a direct effect on the maternal mortality rate. The age pattern of childbearing influences the incidence of obstetric complications, because pregnancies in the early teenage years and at ages over 35 years pose an increased risk to the mother. Fecundity also declines after age 35, and thus postponement of births will increase the need for assisted reproduction. The spacing of births has important health implications; conceptions occurring within 24 months of a previous live birth are at elevated risk of fetal death, prematurity, low birth weight for gestational age, and infant mortality. Unintended pregnancies may result in induced abortion, which in many countries is restricted and unsafe.

Fertility also affects public health indirectly through socioeconomic pathways. Birth rates are the crucial determinant of population growth (or decline) and the age structure of populations, and both factors have profound socioeconomic implications. Countries growing at 2% per year or more (implying a doubling in population size every 36 years or less), because mortality has declined but fertility remains high, face greater difficulties in escaping from poverty and illiteracy than other countries, mainly because nearly half the population is aged under 15 years, thus placing a heavy dependency burden on the adult population. When fertility falls, an era of several decades follows when the labor force is proportionately large, the dependency burden is atypically low, and prospects for making rapid socioeconomic progress are especially bright. This era is inevitably followed by a return to a high-dependency burden because of an increase in the elderly population, which poses a strain on governments’ health and welfare budgets.

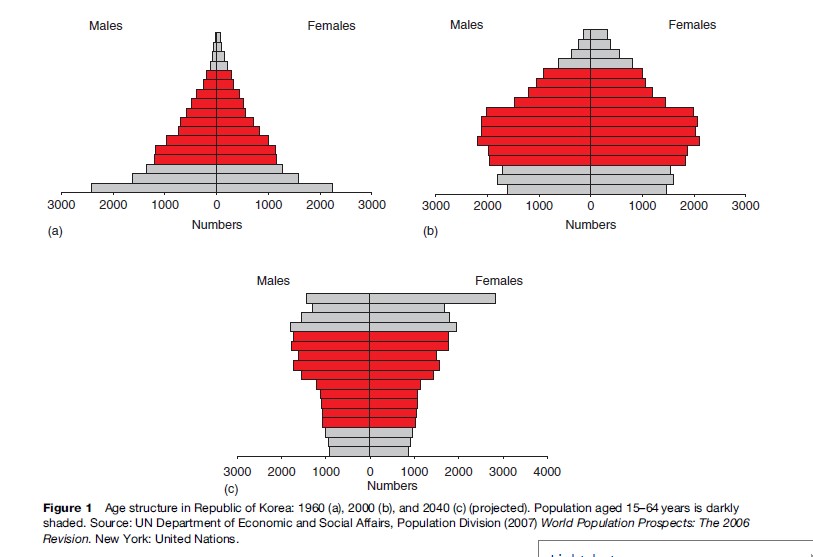

The sequence is well illustrated by the case of the Republic of Korea (Figure 1). By 1960, mortality had already declined but fertility remained high at about six births per woman, and the population was growing at 2.8% per year. At that time, 42% of the total population was aged under 15 years but only 3% were aged 65 or more. In the next 40 years, fertility fell sharply and by 2000 the number of births per woman was about 1.4 and the growth rate had abated to 0.6% per year. Between 1960 and 2000 the number of working-age adults (15–64 years) per 100 dependants rose from 120 to 250. Between 2000 and 2040 it is projected that the proportion of Korea’s population aged 65 or more will rise from 7.4% to 30.5% and the ratio of workers to dependants will have fallen from 250 to 137 per 100 dependants. All industrialized countries now face similar problems of population aging.

In the absence of any constraints, it is estimated that the average number of births per woman would be about 15. In all societies, fertility is held well below this biological maximum by a blend of four main factors: restrictions on sexual intercourse, typically operating through marriage systems; lactation that inhibits ovulation; contraception; and induced abortion. The highest fertility recorded for a national population was 8.7 births per woman in Yemen between 1970 and 1985. In premodern societies, fertility was typically in the range of four to six births.

Between 1950 and 2005, the global fertility rate halved from about five to 2.5 births. Under conditions of moderate to low mortality, a little over two births per woman is required to bring about long-term stabilization of population size. Thus, the world as a whole may be approaching the end of an era of sustained growth, from 1 billion in 1830 to 6.5 billion in 2005 and a projected total of 9.2 billion in 2050 (United Nations, 2006). However, these global figures mask huge differences between regions and countries. The level of childbearing in most industrialized countries has fallen well below the two-child mark and therefore these countries face the possibility of population decline, combined with population aging. Conversely, many of the poorest countries in the world still retain buoyant fertility levels and can expect substantial increases in population size. In this research paper, fertility trends since 1950 will be described and the underlying causes and implications discussed.

Trends In Industrialized Countries

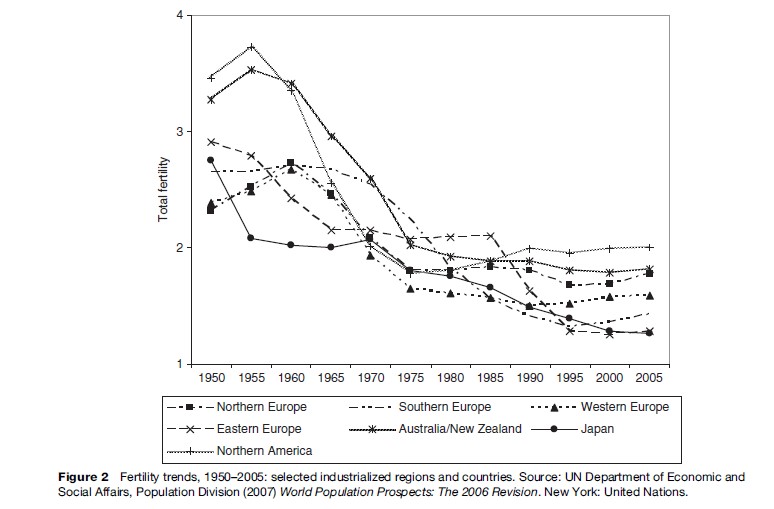

In most of Europe and in North America, fertility decline started in the late 19th century (well before the development of modern contraceptives) and birth rates fell to low levels in the Great Depression of the 1930s, giving rise to concerns about population decline. These concerns were short-lived because, following the end of World War II, fertility rose in most industrialized countries and in some it continued to rise throughout the 1950s (Figure 2). This postwar baby boom was most pronounced in the United States, where fertility climbed from 2.9 births in 1946 to peak at 3.7 births in 1957. Japan is the clearest exception: This country experienced a dramatic decline from 4.5 births in 1947 to 2.0 births a decade later, partly in response to a shift from proto antinatalist policies and liberalization of abortion laws.

The mid-1960s marked the start of a second and unforeseen phase of fertility decline. By 1980, fertility in most (developed) countries had fallen below the replacement level of two births. In 2005, childbearing was below 1.5 births in Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, the Russian Federation, and much of Eastern Europe, and also in the economically advanced East Asian states and territories ( Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, Republic of Korea). Some of this decline can be attributed to increased efficiency in the prevention of unintended births. The advent of oral contraception in the 1960s represented a decisive break of the sex–reproduction nexus. Access to legal abortion was also made easier in many countries. In 2000, about 20% of known pregnancies were legally terminated in France, Norway, Denmark, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. This percentage exceeded 40% in many countries of the former Soviet bloc and the Russian Federation itself (United Nations, 2005). In the United States, the fraction of births reported by women as unwanted fell from 20% in the early 1960s to 7% by the late 1970s, and the same trend no doubt occurred in many industrialized countries, though is less well documented.

However, most commentators have sought explanations in more fundamental changes than improved birth control. The fertility decline in many industrialized countries has been accompanied and partly propelled by postponement of marriage and parenthood, rises in cohabitation, nonmarital births, and divorce, increased acceptance of diverse sexual lifestyles, and a growing independence of women. These interwoven features, dubbed the ‘second demographic transition,’ represent an appreciable departure from marriage and parenthood as the central pillars of adult life. The key underlying cause is identified by some as the changing roles of women in society, together with the sluggish adaptation of men to this emancipation, for instance, by reluctance to shoulder a more equal share of the burden of housekeeping and child-rearing. The shift away from marriage and motherhood has been called ‘the revenge of women on men.’ Paradoxically, however, the level of childbearing is lowest in countries where women’s labor force participation is also very low: Japan, Greece, Italy, and Spain. It is also of note that these same countries have low proportions of nonmarital births. Other experts, such as Ronald Lesthaeghe and Dirk van de Kaa, have sought an explanation in the development of broader ‘postmodern’ values of individualism, secularism, and the desire for self-fulfillment. Compelling region-specific explanations abound. For instance, the turbulence and insecurity caused by the break-up of the Soviet bloc coincides with the period of sharpest decline in these countries. Given the economic, social, and cultural diversity of the very-low-fertility countries, it seems unlikely that there is a single underlying cause.

A sustained fertility rate of 1.5 births implies a halving of population size approximately every 65 years. While this prospect of population shrinkage is welcomed by some environmental groups, it is regarded with alarm by many European and Asian governments. International migration on a sufficient scale to offset low birth rates and prevent population decline does not appear to be politically feasible. Hence, the main policy responses have been aimed at stimulating reproduction and have included generous maternity/paternity allowances (Sweden), child allowances that increase with parity (France), and cash payments at birth (Australia, Italy). Many other countries have shunned explicit pronatalist policies but have attempted to make family building and work more compatible, for instance, by better provision of infant care centers. None of these policies can claim long-term effectiveness at raising birth rates, and the demographic futures of industrialized countries is uncertain (Gauthier, 1996). While most experts foresee the continuation of very low fertility, the United Nations envisages a slight but steady increase over the next 40 years. One factor favoring an increase concerns postponement of births, which depresses period rates but may not affect the number of children that women have over their life course. Sooner or later, the trend toward delayed childbearing must end and, when this happens, period fertility rates will increase, typically by an average of 0.2–0.4 births per woman (Lutz et al., 2003). It is also true that a two-child family remains a widespread aspiration despite downward shifts in some countries (Goldstein et al., 2003).

Trends In Developing Regions

In Asia, Latin America, and to a lesser extent Africa, life expectancy increased sharply while birth rates remained high in the two decades following World War II. The resulting acceleration of rates of population growth rang alarm bells because of evidence that socioeconomic progress would be jeopardized. Key U.S. leaders, such as President Lyndon Johnson and Robert Mac Namara, president of the World Bank, became convinced of the need to reduce birth rates through the promotion of family planning. In 1969, the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (now the United Nations Population Fund – UNFPA) was created, with the shrewd choice of a Filipino Roman Catholic as its first executive director. Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) surveys indicated the existence of favorable attitudes toward smaller family sizes and contraception in many poor countries. Pilot programs in Taiwan and the Republic of Korea showed that a ready demand existed for modern contraception, specifically the intrauterine device. Thus, the stage was set for a novel form of social engineering, the reduction of fertility through government-sponsored family planning programs. The number of developing countries with official policies to support family planning rose from two in 1960 to 115 by 1996.

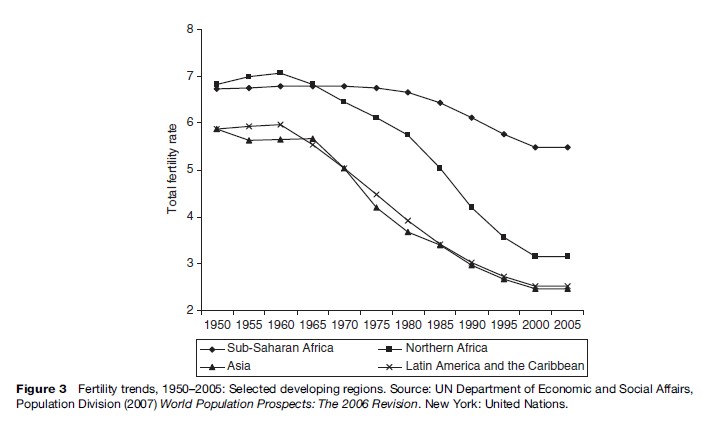

Between 1950 and 2005, fertility in both Asia and Latin America fell from a little under six births per woman to about 2.5 births (Figure 3). The main exceptions are Afghanistan, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Pakistan in Asia, and Guatemala, Bolivia, and Paraguay in Latin America. In the Arab states of North Africa, the corresponding decline was from 6.8 births to 3.2 births. Only in subSaharan Africa does fertility remain high at 5.5 births.

The relative influence of family planning promotion and socioeconomic development (in particular, increased life expectancy and education, which raise the number of surviving children and the costs of rearing them) on fertility trends is hotly contested. In most Latin American countries, the role of state intervention has been minor. Governments in this region were hesitant to promote birth control partly because of the influence of the Roman Catholic church, and early efforts to popularize contraception were spearheaded by nongovernmental organizations with the prime objective of reducing illegal and unsafe abortions. The imprint of government actions can be more clearly discerned in Asia, notably in China, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. In China, programs to reduce population growth started in 1972 and, in the next seven years, fertility fell sharply – but not sufficiently, in the opinion of government planners. In 1979, the one-child policy was enacted and enforced rigorously in urban areas, where fertility fell quickly to one child. In rural areas, however, there was entrenched resistance and in the 1980s policy implementation in many provinces was relaxed to permit two children, particularly if the first born was a daughter (Gu et al., 2007). China’s fertility is currently estimated to be 1.7 births per woman. Because of the vast size of China’s population, government policies in this country have made a major contribution to global stabilization but the price has also been high: denial of reproductive freedom, sex-selective abortion, abandonment of daughters, and instances of female infanticide.

In Bangladesh, one of the poorest and least literate countries in Asia, governments, faced with a highly visible population problem, had little choice but to address it as a top priority. Starting in 1975, a comprehensive family planning service was created, accompanied by incessant publicity through the mass media and other channels. Between 1975 and the 2000, fertility halved from six to three births per woman – a vivid demonstration that poverty and illiteracy are not incompatible with small families.

The demographic histories of the Philippines and Indonesia also demonstrate that high educational levels and reasonably high status of women, factors thought to be particularly conducive to low fertility, do not always have this effect. In 1960, the Philippines was one of the wealthiest countries of Southeast Asia. The level of adult literacy was 72%, compared with only 39% in Indonesia. Income per head was almost double the Indonesian level at that time, life expectancy was 10 years longer, and infant mortality correspondingly lower. It came as no surprise, therefore, that fertility decline started earlier in the Philippines than in Indonesia. However, since the mid-1970s, the pace of decline has been much greater in Indonesia; the level of fertility in 2000–05 was estimated to be 2.5 births, one birth lower than in the Philippines.

The explanation for this unexpected outcome lies well beyond the realm of statistical evidence, but almost certainly involves the intertwined factors of religion and government policy. The Indonesian government skillfully evaded the potential danger of opposition from Islamic leaders by eschewing abortion and contraceptive sterilization. It mounted a very forceful family planning program, with considerable community pressure on couples to adopt birth control (Warwick, 1986). In the Philippines, no compact between church and state was reached, and Roman Catholic leaders remain strongly and openly opposed to modern birth control. This opposition has both inhibited the evolution of comprehensive family planning services and no doubt influenced the climate in which reproductive decisions are taken.

The persistence of rather high fertility in the Philippines is made even more surprising in view of the relatively high status of women in that country. Educational levels for women are exceptionally high, as is labor force participation. However, the example of the Philippines suggests that the status of women – if defined in terms of participation in public life, including paid employment – is not such an important precondition for sustained fertility decline as so often claimed. Indeed, it is probably more a consequence of decline than a cause.

Though fertility in sub-Saharan Africa remains high on average, the subregion is demographically diverse. In the Republic of South Africa and Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia), vigorous family planning promotion started before the advent of majority rule and fertility in both countries, and in Botswana is now at a relatively low level. HIV epidemics in southern Africa are especially severe and thus falling fertility has been accompanied by rapidly rising mortality. These countries face an exceptionally abrupt end to an era of population growth.

In eastern Africa, fertility decline has started in most countries, but most markedly in Kenya. In that country, a vigorous family planning effort was initiated in the early 1980s and, in the next 15 years, fertility fell from nearly eight to 4.8 births. Unexpectedly, the rate then plateaued, one likely reason being that funds and energy were diverted from family planning to HIV/AIDS. Between 1988 and 2003, the proportion of contraceptive users relying on government services dropped from 68% to 53% and the percentage of births reported by mothers as unwanted rose from 11% to 21% (Westoff and Cross, 2006). Both trends imply a deterioration of government services. In 2002, the United Nations projected Kenya’s population in 2050 at 44 million. In 2004, this projection was raised to 83 million, mainly in response to the fertility stall but also to a reduction in expected AIDS-related mortality.

This sequence of events in Kenya may be an extreme example of a more pervasive trend throughout much of the region. Rather than gathering pace in the past 15 years, the trend toward lower fertility has faltered. In west and central Africa, fertility typically remains close to six births per woman, contraceptive use prevalence among married women remains below 10%, and desired family sizes are still high. The United Nations projects that fertility in sub-Saharan Africa will decline steadily to reach 2.5 births by midcentury. Even if this projection is accurate, Africa’s population is set to rise from 0.77 billion in 2005 to 1.76 billion in 2050. Most countries will double in population size in the next 40 or so years, and some will triple in size.

Is the persistence of high fertility throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa simply a reflection of low socioeconomic development or of distinctive features of culture and social organization that set the region apart from Asia and Latin America? Certainly, standards of living for many Africans worsened in the 1990s, but equally high levels of poverty and illiteracy did not stifle fertility transition in Asia, as trends in Bangladesh and Nepal since the 1980s show. It is also true that countless surveys reveal that Africans attach a higher value to large families than citizens elsewhere. According to Caldwell, the explanation for this pronatalism lies in the subordination of the nuclear family to the lineage. For lineage leaders, the patriarchs, high fertility is advantageous because it enhances their prestige, power, and patronage. Thus, they see children as sources of wealth rather than as drains on emotional and financial resources. A related explanation stems from the multiplicity of ethnic and linguistic groups in Africa, with the inevitable tension and conflict over resources that this diversity implies. A buoyant birth rate and numerical strength may well have conferred advantage in these circumstances, thus engendering strongly pronatalist values.

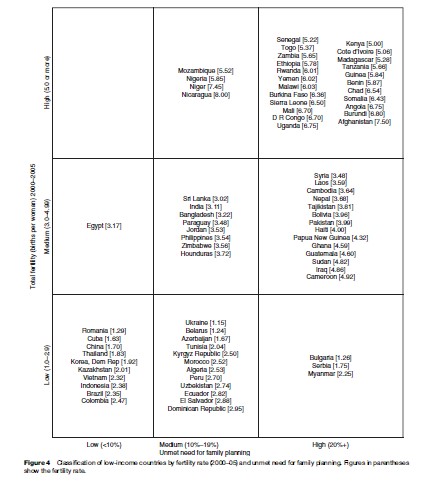

Since the most recent International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, in 1994, policies to reduce population growth through family planning promotion have fallen from fashion and been replaced by a broader agenda of women’s reproductive health and rights. The topic of population has been marginalized in key reports on development and was omitted from the Millennium Development Goals. International funding for family planning has fallen. This neglect may prove to be mistaken. Figure 4 shows a display of the 76 poorest countries with a current population of 5 million or more, by fertility rate (2000–05) and by the level of unmet need for family planning – defined as the percent of married women who want no child for at least 2 years but are using no method of contraception. Over one-third of these countries, mostly in Africa, still have high fertility of five births or more per woman, and the vast majority of these countries also have a high unmet need for family planning. In a further 25 countries, fertility is in the range of three to five births, well above replacement level.

Conclusions

For millennia, the human population grew at a miniscule rate because moderate fertility was matched by high, albeit fluctuating, mortality. The scientific and technological revolution of the past 200 years broke this demographic balance and gave rise to an unprecedented surge in human numbers. The past 50 years has seen a necessary and welcome return toward balance; fertility has fallen in most countries, and world population may stabilize in the latter half of this century. Thus, the prospect of the Malthusian nightmare of famine and warfare, so prominently proclaimed in the 1960s by Paul Ehrlich and others, has receded.

No consensus on the ideal level of fertility exists, but a range of 1.7 to 2.3 births per woman has much to recommend it, as it implies modest growth or decline. As shown in this research paper, the world is still far away from such a benign outcome. Fertility rates in many industrialized countries have plunged well below 1.7 while many poor countries have rates well above 2.3. Indeed, the fertility of nations has rarely been so diverse. Our demographic future is still uncertain. Will birth rates in Africa fall as fast and pervasively as in Asia and Latin America, and will fertility edge steadily up in countries such as Japan and Italy? What happens in Africa is partly a matter of political priorities because a large body of successful experience at reducing fertility has accumulated. Policies to raise fertility do not have a successful track record, and so trends in low-fertility countries are particularly difficult to predict.

Bibliography:

- Gauthier AN (1996) The State and the Family: A Comparative Analysis of Family Policies in Industrialised Countries. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Goldstein J, Lutz W, and Testa MR (2003) The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review 22(5–6): 479–496.

- Gu B, Wang F, Guo Z, and Zhang E (2007) China’s local and national fertility policies at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review 33: 129–147.

- Lutz W, O’Neill BC, and Scherbov S (2003) Europe’s population at a turning point. Science 299: 1991–1992.

- United Nations (2005) The New Demographic Regime: Population Challenges and Policy Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: Economic Commission for Europe and United Nations Population Fund.

- United Nations (2006) World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision. New York: Department of Social and Economic Affairs, Population Division.

- Warwick DP (1986) The Indonesian family planning program: Government influence and client choice. Population and Development Review 12: 453–490.

- Westoff C and Cross A (2006) The Stall in the Fertility Transition in Kenya. Demographic and Health Surveys Analytical Study No. 9. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro.

- Caldwell JC and Caldwell P (1987) The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 13: 409–437.

- Caldwell JC and Schidlmayr T (2003) Explanation of the fertility crisis in modern societies: A search for commonalities. Population Studies 57: 241–264.

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, and Innis J (2006) Family planning: The unfinished agenda. Lancet 368: 1810–1827.

- Davis K, Bernstam MS, and Ricardo-Campbell R (eds.) (1986) Belowreplacement fertility in industrial societies: Causes, consequences, policies. Population and Development Review, 12 (supplement).

- Guzma´ n JM, Singh S, Rodr´guez G, and Pantelides EA (eds.) (1996) The Fertility Transition in Latin America. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Kirk D (2000) The demographic transition. Population Studies 50: 361–388.

- Leete R and Alam I (eds.) (1993) The Revolution in Asian Fertility: Dimensions, Causes and Implications. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Lesthaeghe R and Meekers D (1986) Value changes and the dimension of familism in the European community. European Journal of Population 2: 225–268.

- van de Kaa DJ (2001) Postmodern fertility pBibliography: From changing value orientation to new behavior. In: Bulatao RA and Casterline JB (eds.) Global Fertility Transition. Population and Development Review, pp. 290–331.

- http://www.populationaction.org – Population Action International.

- http://www.prb.org – Population Reference Bureau.

- http://www.un.org/esa/population/unpop.htm – United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/default.htm – United Nations Statistics Division.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.