This sample Urban Health in Developing Countries Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

The future of our planet now seems irrevocably urban, and we need to be sure that this urban life is healthy, equitable, and sustainable. A major study in 2007 by the Worldwatch Institute reported that ‘‘by 2005, the world’s urban population of 3.18 billion people constituted 49 percent of the total population of 6.46 billion. Very soon, and for the first time in the history of our species, more humans will live in urban areas than rural places’’ (Lee, 2007:4).

These findings were based on United Nations (UN) projections suggesting that nearly all of the population growth in the future will be in cities and towns. Most notably, this population growth will be in low and middle-income nations. Asia and Africa, today the most rural continents of the world, are projected to double their urban populations, from 1.7 billion in 2000 to about 3.4 billion in 2030. Overall there will be 60 million new urban citizens every year living in the towns and cities of the poorest countries (UN Population Division [UNPD], 2006; Lee, 2007).

This research paper discusses the public health challenge of urbanization. It looks at current trends in urban demography, discusses the state of urban health, and concludes with a brief outline of some current urban policy options.

The Scale Of Urbanization

Urban areas in developing countries now have more than a third of the world’s total population, nearly three quarters of its urban population and most of its large cities. They contain most of the economic activities in these nations and most of the new jobs created over the last few decades. They are also likely to house most of the world’s growth in population in the next one to two decades (UNPD, 2006). Thus, how they are governed and what provisions are made to house and service their expanding populations has very large implications for economic and social development – and for public health.

Urbanization in developing countries needs to be understood as part of a global trend toward increasingly urbanized patterns of production; changes in urbanization levels in all the world’s regions and most of its nations follow the increasing proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) generated by industry and services and the increasing proportion of the economically active population working in industry and services. The world’s urban population in 2007 was around 3.2 billion people (UNPD, 2006) – more than the world’s total population in 1960. By 2007, half of the world’s population lived in urban centers compared to less than 15% in 1900 (Satterthwaite, 2007a). Many aspects of urban change in recent decades are unprecedented, including not only the world’s level of urbanization and the size of its urban population, but also the number of countries becoming more urbanized and the size and number of very large cities. The populations of dozens of major cities have grown more than 10-fold in the last 50 years, and many have grown more than 20-fold (Satterthwaite, 2007a). There are also the large demographic changes apparent in all nations over the last 50 years that influence urban change, including rapid population growth rates in much of Latin America, Asia, and Africa after the Second World War (although for most these have declined significantly), and changes in the size and composition of households and in age structures (Montgomery et al., 2003).

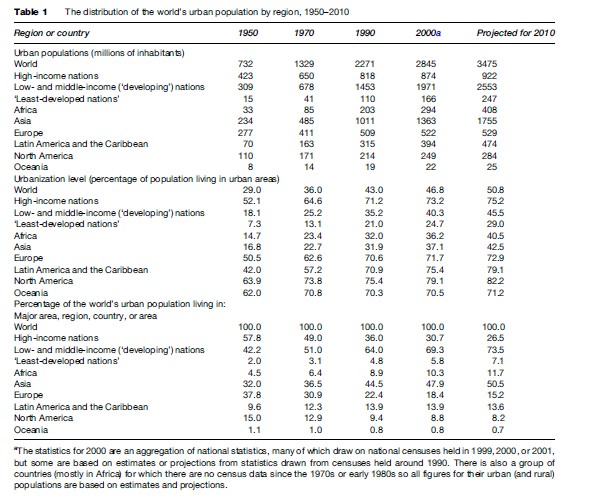

Table 1 shows the scale of urban population growth since 1950; it also shows how the proportion of the world’s urban population living in different regions and between high-income and developing countries has changed. Since 1950, most of the growth in the world’s urban population has been in developing nations. Developing countries in Asia contain close to half the world’s urban population. Africa now has a larger urban population than North America or Western Europe, even though it is generally perceived as overwhelmingly rural. In 1950, Europe and North America had more than half the world’s urban population; by 2000, they had little more than a quarter. Africa had 10% of the world’s urban population in 2000 compared to less than 5% in 1950. Asia increased its share of the world’s urban population from less than one-third to nearly one-half in these same five decades and most of this was in developing nations.

The Growth Of Large Cities

Two aspects of the rapid growth in the world’s urban population since 1950 are important to understand in the context of urban health: the increase in the number of large cities and the historically unprecedented size of the largest cities. Just two centuries ago, there were only two ‘million-cities’ worldwide (i.e., cities with 1 million or more inhabitants) – London and Beijing (then called Peking). By 1950, there were 75; by 2000, 380. A large (and increasing) proportion of these million-cities are in developing countries.

The average size of the world’s largest cities has also increased dramatically. In 2000, the average size of the world’s 100 largest cities was around 6.3 million inhabitants. This compares to 2.0 million inhabitants in 1950, 728 270 in 1900 and 187 520 in 1800 (Satterthwaite, 2007a). While there are various examples of cities over the last two millennia that had populations of 1 million or more inhabitants, the city or metropolitan area with several million inhabitants is a relatively new phenomenon – London being the first to reach this size in the second half of the 19th century. By 2000, there were 45 cities with more than 5 million inhabitants.

Aggregate urban statistics can be interpreted as implying comparable urban trends across the world or for particular continents. But they obscure the diversity in urban trends between nations. They also hide the particular local and national factors that influence these trends. Aggregate urban statistics may suggest rapid urban change, but the rate of increase in urbanization levels, and the rate of increase of urban populations, has slowed in many developing countries. Many of the world’s largest cities, including Mexico City, Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, Calcutta, and Seoul had more people moving out than in during their last intercensus period. The increasing number of megacities with 10 million or more inhabitants may seem to be a cause for concern but there are relatively few of them (17 by 2000). In this year, they concentrated less than 5% of the world’s population and most are in the world’s largest economies. Also, taking a longer-term view of urban change, it is not surprising that Asia has most of the world’s largest cities as this reflects the region’s growing importance within the world economy (and Asia has many of the world’s largest national economies).

Urban Change And Economic Change

Although rapid urban growth is often seen as a problem, it is generally the nations with the best economic performance that have urbanized most in the last 50 years. In addition, perhaps surprisingly, there is often an association between rapid urban change and better standards of living. Not only is most urbanization associated with stronger economies but generally, the more urbanized a nation, the higher the average life expectancy and the literacy rate and the stronger the democracy, especially at the local level. Many of the largest cities may appear chaotic and out of control, but most have life expectancies and provision for piped water, sanitation, schools, and health care that are well above their national average – even if the aggregate statistics for each megacity can hide a significant proportion of their population living in very poor conditions. Some of world’s fastest growing cities over the last 50 years also have among the best standards of living within their nation – as in the case of Porto Alegre in Brazil (Menegat, 2002).

It is also important not to overstate the speed of urban change. Recent censuses show that the world today is also less urbanized and less dominated by large cities than had been anticipated. For instance, Mexico City had 18 million people in 2000 – not the 31 million people predicted 25 years earlier (UNPD, 2006). Calcutta, Sa˜o Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Seoul, Chennai (formerly Madras), and Cairo are among the many other large cities that, by 2000, had several million fewer inhabitants than had been predicted (Satterthwaite, 2007a).

What Drives Urban Change?

Understanding what causes and influences urban change within any nation is complicated. Consideration has to be given to changes in the scale and nature of the nation’s economy and its connections with neighboring nations and the wider world economy, and also to decisions made by national governments, national and local investors, and the 30 000 or so global corporations who control such a significant share of the world’s economy. Urban change within all nations is also influenced by the structure of government (especially the division of power and resources between different levels of government), and the extent and spatial distribution of transport and communications investments. The population of each urban center and its rate of change are also influenced not only by such international and national factors but also by local factors related to each very particular local context – including the site, location, natural resource endowment, demographic structure, existing economy, and infrastructure (the legacy of past decisions and investments) and the quality and capacity of public institutions.

The immediate cause of urbanization is the net movement of people from rural to urban areas. The main underlying cause is the concentration of new investment and economic opportunities in particular urban areas. Virtually all the nations that have urbanized most over the last 50–60 years have had long periods of rapid economic expansion and large shifts in employment patterns from agricultural/pastoral activities to industrial, service, and information activities. In developing countries, urbanization is overwhelmingly the result of people moving in response to better economic opportunities in the urban areas, or to the lack of prospects in their home farms or villages. The scale and direction of people’s movements accord well with changes in the spatial location of economic opportunities. In general, it is cities, small towns, or rural areas with expanding economies that attract most migration, although there are important exceptions in some nations, such as migration flows away from wars/conflicts and disasters. By 2004, 97% of the world’s GDP was generated by industry and services and around 65% of the world’s economically active population works in industry and services, most of which is located in urban areas. Political changes have had considerable importance in increasing levels of urbanization in many nations over the past 50–60 years, especially the achievement of political independence and the building of government structures that were important for most of Asia and Africa; however, these had much less effect in most nations from the 1980s onward.

Agriculture is often considered as separate from (or even in opposition to) urban development, yet prosperous, high-value agriculture, combined with prosperous rural populations, has proved an important underpinning to rapid development in many cities. Many major cities first developed as markets and service centers for farmers and rural households, and later developed into important centers of industry and/or services. Many such cities still have significant sections of their economy and employment structure related to forward and backward linkages with agriculture.

Analyses of urban change within any nation over time serve as reminders of the diversity of this change, of the rising and falling importance of different urban centers, of the spatial influence of changes in governments’ economic policies (e.g., from supporting import substitution to supporting export promotion), of the growing complexity of multinuclear urban systems in and around many major cities – and of the complex and ever-shifting patterns of in-migration and out-migration from rural to urban areas, from urban to urban areas and from urban to rural areas. International immigration or emigration has strong impacts on the population size of particular cities in most nations. But it is not only changing patterns of prosperity or economic decline that underpin these flows of people. Many cities have been impacted by war, civil conflict or disaster, or by the entry of those fleeing them.

What Is Urban Health In Developing Countries?

In many of the towns and cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America – the so-called developing countries, only an urban minority lives in healthy living conditions and has access to good health services, education, and employment. Already, nearly one in two urban dwellers in developing countries live in low-income urban settlements, known pejoratively as slums, with all that this implies in terms of living conditions and health (Lee, 2007). Low-income settlements are areas of a town or city where people have no, or very limited, access to necessities that would secure good health: clean and ample water, sanitation, sufficient living space, and adequate housing are all missing from these environments. Water and food are often biologically contaminated, education and work opportunities are available to a tiny minority and the work that does exist is often in hazardous industries on a wage that does not provide a route out of poverty. Health services are often inaccessible to the urban poor – not because they are at a long distance, as in rural areas, but because poorer people in low-income settlements often do not have the financial means to access them. To make things still more difficult, low-income urban citizens often live with insecure tenure to their land and homes – making the risk of homelessness a regular threat to their well-being.

Both the wealth of a country and scales of urbanization affect urban health patterns. In regions such as Asia, urban populations are huge, but the proportion of urban population in the region as a whole is still less than 50%. In the ‘least-developed’ nations only a quarter of the population is urban. This can affect government and donor policies toward urban areas – and can mean that rural areas are prioritized for basic interventions that affect health (such as vaccination, water and sanitation, and other infrastructure). In contrast, more urbanized regions, such as Latin America, do not have this urban–rural divide in policy terms – which can mean that national policies are aligned to urban priorities. The rate of urbanization is also important for urban health: where rates of urban growth are very high, urban services are quickly overwhelmed and large proportions of the new urban population live without adequate infrastructure – including water, sanitation, housing and transport, but also education, health, and employment.

The Myth Of The Healthy City

There is still a myth among health professionals – the idea that rural peoples are less healthy than their urban counterparts. The myth of the healthy city has been linked for decades to a problem of data aggregation – where total health statistics are sometimes presented for cities with populations greater than those of nation states. Megacities suffer particularly from a problem of super-aggregation, in which health data on the whole city tell only part of the story. Each city’s health will depend on a range of contextual factors, just as a national health profile does.

A key predictor is often the overall state of ‘development’ of the city–measured in proportions of people with clean water, sanitation, adequate housing, and access to health measures such as vaccination and primary care. Thus a megacity with a large proportion of people living in poverty will have a health profile that reflects the profile of these people. However, there is another problem: megacities account for only about 9% of the total urban population of approximately 3.2 billion citizens. Just over half of the world’s city dwellers live in settlements with fewer than 500 000 inhabitants, and we still know little of the health situation in smaller towns and cities internationally.

In every town and city, data that have been broken down by income group tell a different story of urban health – it is the tale of urban inequality. Within cities and towns, disaggregated data show that there are inequalities in living conditions and in access to services such as health, water, and sanitation. There are also inequalities in access to education and work. Thus, it is hard to generalize about urban health profiles, as each city and town may have a distinctive pattern of development and distribution of resources. Even a rich town in a rich country may have sharp inequalities that affect health drastically – for example, a classic study in New York found that black men in Harlem were less likely than men in Bangladesh to reach the age of 65 (McCord and Freeman, 1990).

Urban Health Profiles

Both the physical and the social environment of cities and towns today affect urban health. The overall quality of the urban environment is important for health, and so is the extent of inequality within an urban environment. Some problems of the urban physical environment, such as ambient air pollution, may affect almost everyone in a city. Other problems, such as contaminated water, indoor air pollution, or lack of sanitation, may disproportionately affect some groups more than others. Urban violence may also affect some urban dwellers more than others. Rapid urbanization in most cases exaggerates these problems, as cities are unable to build enough infrastructure and provide enough jobs for an influx of migrants, many of whom may be fleeing war or drought.

In the poorer countries of Africa and Asia a majority of urban citizens live without clean water and sanitation, and with limited public health interventions such as vaccination. This is a consequence of a complex mix of national economic situations, and of the scale and rate of urbanization. In some urban areas, urban health indicators can be worse than in rural areas. In poorer countries, urban areas often have the worst of all worlds–contaminated air, land, and water; deep poverty; and a health profile that includes both the infectious diseases of deep poverty and the so-called diseases of modernity (obesity, cancers, and heart disease). In these cases people carry a double burden of disease that poses a daunting challenge for human health on an urban planet (Stephens and Stair, 2007).

In wealthier countries, such as Brazil in Latin America, most urban people have access to water and sanitation even if their housing is precarious. Urban public health interventions, such as vaccination, are also widespread. In these urban areas, infant mortality rates are low, and urban health problems are linked more to social outcomes, such as educational attainment and employment, and relate to social inequality between urban groups. Urban violence is a major problem in many cities of Latin America, where rates of death from homicide affect adolescent health profiles particularly. In some cities, urban industry affects pollution levels, and the particular mix of industries affects the type of health problems that will be associated with the pollution. The key challenge for urban professionals is to understand the complex mix of urban health problems that result from the unique mix of demographic change, economic development, infrastructure, and social conditions that make up every town and city. The following sections outline some of these urban health challenges in turn.

Infant And Child Survival In Urban Areas

In most low-income and many middle-income nations, infant, child or under-5 mortality rates in urban areas are 5 to 20 times what they would be, if the urban populations had adequate nutrition, good environmental health, and a competent health-care service (Satterthwaite, 2007b). In some low-income nations, these mortality rates increased during the 1990s (Montgomery et al., 2003). However, there are also nations with relatively low urban infant and child mortality rates (e.g., Peru, Jordan, Vietnam, and Colombia) – while there are also particular cities that have achieved low infant and child mortality rates – for instance, Porto Alegre in Brazil (Menegat, 2002).

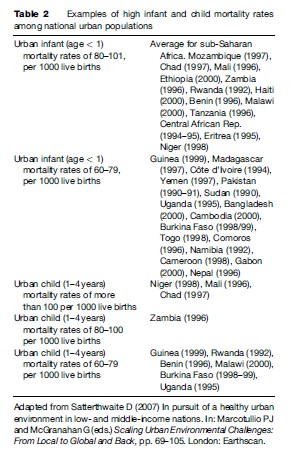

Table 2 gives examples of nations with high infant and child mortality rates within their urban populations. These are all the more surprising in that in all these nations, most middle and upper-income groups live in urban areas and will generally experience much lower infant and child mortality rates. So these ‘averages’ for national urban populations can hide the extent of the problem faced by low-income populations.

The few empirical studies on infant and child mortality rates in low-income urban settlements suggest that these are generally at least twice the urban average. For instance, for Nairobi, Kenya’s capital and largest city, under-5 mortality rates were 150 per 1000 live births in its informal settlements (where over half the population live) and 61.5 for Nairobi as a whole (African Population and Health Research Center [APHRC], 2002).

In virtually all cities in low-income nations for which data are available, and for most in middle-income nations, there are also dramatic contrasts between different areas (districts, wards, municipalities) of the city regarding infant and child mortality rates – as well as in living conditions and other health outcomes (Hardoy et al., 2001; Stephens and Stair, 2007).

Infectious Diseases

In many towns and cities, particularly in Asia and Africa, there is a major lack of water and sanitation facilities. This has huge health repercussions – digestive-tract diseases are a leading cause of death in the world and a major urban health problem (UN Habitat, 2006).

Crowding is another major health hazard for the urban poor. People in low-income settlements often live in highly crowded homes, with four or more people per room, often shift-sleeping and with many children per bed. Contact-related diseases such as measles, tuberculosis (TB), and diarrhea are all linked to living in crowded environments. Notably, some richer cities have such deep pockets of disadvantage that diseases related to urban poverty and crowding have reemerged during periods of increased inequality within the city. A study looking at TB in New York from 1970 to 1990, for example, found an increase in childhood TB in the period and that children living in areas of the Bronx, where over 12% of homes are severely overcrowded, were 5.6-fold more likely than children in other New York neighborhoods to develop active TB (Drucker et al., 1994).

Urban Nutrition

Although undernutrition is generally considered to be a rural problem, the urban poor – forced to pay high prices for food shipped into the city and often unable to grow their own food – can often have the most difficulty obtaining enough nutritious food. This has major impacts on urban nutritional health, particularly for children. A recent analysis of child health in 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa found that differences in child malnutrition within cities were greater than urban–rural differences (Houweling et al., 2006).

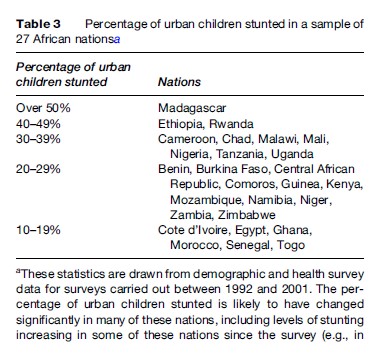

It is common for a third of all urban children to be stunted within the lowest income nations. A study of 10 nations in sub-Saharan Africa showed that the proportion of the urban population with energy deficiencies was above 40% in all but one nation and above 60% in three – Ethiopia, Malawi, and Zambia (Ruel and Garrett, 2004). Table 3 shows this.

As with infant and child mortality rates, there are large differentials in most cities in the prevalence of severe malnutrition between wealthy and poorer areas. For instance, the prevalence of severe malnutrition among boys in the slums of Bangladesh’s two largest cities was nearly two and a half times that in the ‘non-slums’ – measured by the percentage of children aged 12–59 months with mid-upper arm circumference less than 12.5 cm (UNICEF, 2000).

A study of the contribution of illness to poverty in the slums in Dhaka highlights another aspect of the scale of the health burden faced by low-income groups – in this instance, the extent to which ill health caused a deterioration in households’ financial status. In this study of 850 households, ill health was the single most important cause of such deterioration, explaining 22% of cases where households reported a deterioration in their financial status. Illness led to reductions in income and increased expenditures; often more loans taken out, assets sold, and more adults resorting to begging (Pryer, 1993). Although it is dangerous to draw general conclusions from one or two studies, the living conditions described by these two studies are similar to those in informal settlements or tenements in many other urban centers in low and middle-income nations, so comparable links between high health burdens and impoverishment would be expected.

Within this general picture, there are important exceptions. For instance, many Latin American nations that now have predominantly urbanized populations have managed to sustain long-term trends of falling infant and child mortality rates and increasing average life expectancies. This is also true for some Asian and African nations, although the scale of the improvements in urban areas is not clear, as the data are for nations or subnational (state or provincial) units, not for urban populations or particular urban areas.

The industries that power urbanization also create quantities of air pollution in urban areas. The combustion of solid fuels (biomass and coal) in millions of homes can contribute to ambient air pollution. In developing countries, this domestic pollution combines with the greater cocktail of coal-burning industries, diesel trucks or cars, and small, two-stroke motorcycles.

Urban industries do not simply pollute the air – they often contaminate the land and water of the city. This can create a paradoxical kind of urban development: an immediate economic benefit, but at great expense to the health of current and future residents. As with other urban health problems, pollution is concentrated on the poorer people who both live around and work in these industries – in both rich and poor countries. The urban poor may get work – but at what risk? Bhopal in India was perhaps the most notorious example of this kind of urban hazard and inequality: in 1984 more than 40 tons of methyl isocyanate gas leaked from a pesticide plant, immediately killing at least 3800 of the city’s poorest people and causing significant morbidity and premature death for many thousands more (Broughton, 2005). Not only does this kind of urban industrial development often fail to move people out of poverty, it can harm thousands of lives over the long term.

Urban Violence

There is another risk in cities that is not easily addressed with infrastructure interventions such as improved living conditions or infrastructure: urban violence, which is in epidemic proportions in many cities internationally. In some cities violence has actually started to reverse overall trends of health improvement, particularly for young people. For example, a longitudinal study looking at trends in mortality for 15to 24-year-olds in Sa˜o Paulo and Rio de Janeiro from 1930 to 1991 showed a steady improvement in adolescent health until the 1980s, when death rates started to rise again due to violence (Vermelho and Jorge, 1996). The death rate due to violence can be up to 11 times higher for young people from the poorest communities than the rate for young people from a wealthier community (Stephens, 1996).

In Brazil, urban violence takes an enormous toll on poor young men in terms of both mortality and morbidity: death rates from homicide in Brazilian state capitals in 2003 for young men aged 20–24 were 133 per 100 000. This means that 1 child in every 1000 will be a victim of homicide in these cities, a rate higher than that of any childhood cancer. The United States has a similar problem, with violence affecting principally economically disadvantaged young urban men from ethnic minorities, who are disproportionately represented in jails and in homicides (Gawryszewski and Costa, 2005).

Injuries related to traffic accidents and violence are now respectively the second and fourth causes of hospitalization in Brazilian cities. This makes trauma treatment a top priority for urban health services in this country and challenges health systems that are generally better prepared for infectious or chronic diseases (De Souza and de Lima, 2006).

The fear of violence can also be a significant hindrance to mental well-being. Long-term anxiety, stressful life events, lack of control over resources, and lack of social support are all key preconditions for depression. Poor women in cities are often the most vulnerable group.

Double Burdens

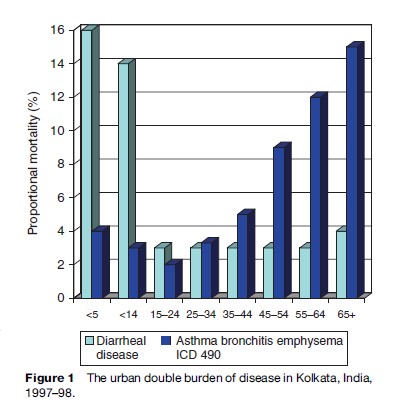

In many cities and towns of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, ‘modern’ diseases such as asthma, heart disease, and cancer are arriving in places that have yet to fully get a handle on ‘old’ diseases such as TB, cholera, and diarrhea. Figure 1 illustrates the double burden of disease brought by dirty industrial development and polluting motor vehicles in Kolkata, India (Stephens, 1999). Up to 40% of people still live in poverty, but the route to development is sought through highly polluting industries, and providing service to millions of people remains a dream. Figure 1 shows the cause of death by age – demonstrating, albeit crudely, that if people in Kolkata survive the insults of contaminated water, they live on to experience the severe risks of highly contaminated air. This double burden is particularly exaggerated in unequal cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where affluent people are increasingly dealing with expensive modern maladies such as diabetes and heart disease while lower income people are still plagued by undernutrition and infectious disease.

Urban Health Inequalities

A critical issue of urban health, but perhaps the most important of all, is that of urban inequalities and their impacts on health. Health inequalities are a problem internationally, but cities have become the nexus for both deepest poverty, and also extreme wealth. This inequality spans across almost all urban resources including land, food, water, shelter, education, health services, and work opportunities. As a consequence, urban health inequalities also span many health outcomes, as the previous sections have outlined – infectious disease inequalities are linked to unequal access to water and sanitation resources, while violence can be linked to social unrest at gross socioeconomic disparities.

But this is not just an issue of differential access to resources. It is also an issue of inequity. For example, unequal access to water in cities is not a simple issue of one group having less access to water than another in the city: the urban poor pay more in absolute and relative terms for potable water than their wealthier urban counterparts (Cairncross and Kinnear, 1992). Meanwhile, richer urbanites may use their cheaper water for watering their gardens or filling their swimming pools. At times of water shortage these inequalities become more pronounced – and richer urban citizens may be the only group with a constant supply of water – while costs of water may increase still further for poorer people. These costs impact on poorer households severely – using a large proportion of their income on water and skewing the family budget away from other essentials (Satterthwaite, 2007b).

Perhaps most difficult to address, many studies link the high rates of urban violence to the gross urban inequalities seen in cities and towns of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Many urban young people grow up in grave environmental and social poverty, unable to fulfill even their basic aspirations. Meanwhile their neighbors may live in absolute affluence directly alongside these disadvantaged youth. Many young people, particularly young men, are drawn into urban violence through social frustration or the lack of productive alternatives to occupations linked to violence – for example, drug gangs often provide work for young urban people, but it is dangerous work requiring weapons. Some analysts see this violence as an occupational hazard linked to high-risk professions for urban, poor boys who have few alternatives to this violent option. Urban violence is also linked more generally to urban inequality and this picture is true in cities internationally (Pan American Health Organization, 1990; Pinheiro, 1993; Wilson and Daly, 1997; Gawryszewski and Costa, 2005).

The Growing Threat Of Climate Change

An article on urban health in the twenty-first century cannot conclude without some mention of the links of urban health with climate change. Climate change will affect the whole planet. However, it is increasingly evident that cities are one of the main generators of climate change, and that their urban peoples will be some of the most directly affected, by impacts of the changing climate. This includes impacts through temperature changes (both heat and cold), but also through extreme weather events, which hit densely populated urban areas particularly hard and often very fast. Studies show that urban citizens have adapted well to their urban ecosystem and have developed shelter that protects them from locally familiar heat and cold (Carson et al., 2006). But unexpected changes to these temperatures can affect people greatly – particularly vulnerable groups such as the very young and the elderly. Heat-related deaths, for example, can occur rapidly in extreme daily heat episodes. These impacts can affect people even in cities such as Delhi where the population is more used to extreme heat (Hajat et al., 2005).

Coastal cities might be particularly at risk of extreme weather events, and, since historically trade was by water and sea, many major cities are on coasts or major rivers. In an important workshop held in 2005 on Climate Change and Urban Areas, Professor Rob Nicholls, of the Tyndall Centre and University of Southampton, reported that 1.2 billion people lived along coastal areas with low elevation and were at significant risk of rising sea levels and extreme weather events (UCL Environment Centre and British Embassy Berlin, 2005).

Conclusions: Policies Toward Urban Health

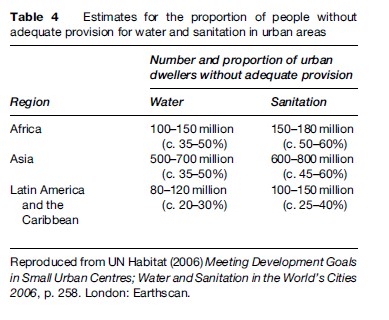

The first major concern of urban health internationally is to improve basic public health in urban areas of developing countries. Around half the urban population in Africa and Asia lack provision for water and sanitation to a standard that is healthy and convenient (Table 4). For Latin America and the Caribbean, more than a quarter lack such provision. Inadequate provision for water and sanitation contributes to many of the health problems and the high levels of infant and child death described in earlier sections. Public health improvements are especially important for the 900 million or so urban dwellers who live in very overcrowded dwellings in tenements or shacks lacking basic infrastructure and services. This should include a focus not only on large or fast-growing cities, but also on smaller urban centers, as these contain a high proportion of the urban population in developing countries.

Concentrations of people in urban areas make it easier and cheaper to provide good-quality piped water, sanitation, and drainage. There are many examples showing this – where informal/illegal settlements with a predominance of low-income households have been provided with good-quality provision for water and sanitation at low unit costs – and in many instances with close to full cost recovery from the inhabitants (UN Habitat, 2006). But these are still the exception – and in the absence of good provision, this concentration of people and their wastes greatly increases health risks from a great range of waterborne, water-washing, or water-related diseases.

It may be that trends in macroeconomic inequality will have severe effects on the urban poor. There is some evidence of this from two very different contexts: Studies in the United States looking at trends in mortality between the 1970s and 1990s found that African-Americans living in cities experienced extremely high and growing rates of excess mortality compared with rural and wealthier communities (Geronimus et al., 1999). A similar study in five African countries of rising death rates for children under the age of five between the 1980s and 1990s found that in Zimbabwe the increase was largest among urban children (Houweling et al., 2006).

In this context, what can we do to encourage the move toward healthier cities? There is evidence that urban inequalities decrease when local governments listen to low-income residents and when such individuals are included in urban plans and actions. Inequalities may also lessen when health is used as a criterion to establish priorities for urban policy. In Kolkata, India, for example, an environment and development plan was based on health priorities and on a consultation weighted toward the views and needs of the poorest citizens. This did not change the city overnight, but it gradually put the needs of the urban poor on the policy agenda. There are also many successful stories of self-help in water and sanitation – where health and city equality have both improved when local governments work with local people.

Donors, too, who are seeking to help the urban poor, can better support health by listening to them. Looking for a set of best practices, the World Bank embarked on an institute-wide analysis of 45 participatory urban development programs in the 1990s. The final report concluded that community participation was absolutely essential for any slum-upgrading projects. The authors noted that the people who must move their homes to make way for roads, public spaces, and sewage lines ‘‘must be involved in the decision making process if they are to cooperate with it.’’ The report further concluded that community participation was ‘‘the single most important factor in overall quality of project implementation – efficiency, effectiveness, timeliness, responsiveness, and accountability’’ (Imparato, 2003: 10).

In some countries, such as Brazil, recent local and national government strategies have systematically supported governance and budget setting that gives priority to the needs of the urban poor and that puts public services high on the overall agenda. Local government support to the efforts of low-income city dwellers can have effects on a surprising range of health challenges. In Ilo, a small port town in Peru, for example, air pollution policy finally got on the agenda when communities were included in debates with the local mining company, and access to public services increased dramatically as community concerns were included in local planning and budgeting. Green spaces increased, water contamination decreased, and sustainable development gradually rose in importance on the agenda. During this period the mayor noted that Ilo’s people and their mobilization put the environment, poverty, and equity high on the agenda – all themes that affected urban health (Palacios and Sara, 2005).

It is not just inequalities in the physical environment of cities that can be improved with more involvement of citizens. It is notable that some of the most intractable problems of urban inequality – such as urban violence – are often only tackled in this way. It is young people who are most affected by urban violence, and the urban poor are often in constant threat of violence – either from young people in other poor areas or from the police. Interestingly, young people themselves often have the solutions. For example, young men from one of the most difficult favelas of Rio de Janeiro started a musical alternative to drug gangs, eventually spreading their combination of music and education to other favelas and starting a health education program for young women and men (Grupo AfroReggae, 2007).

Climate change too, can be addressed in cities. As the participants of the 2005 UCL Environment Centre workshop on Climate Change and Urban Areas concluded the world’s major cities are large contributors to CO2 emissions but also

[f]undamental to global GDP, realistic strategies for the curbing of greenhouse gases and the reduction of its worst effects were regarded as essential both for climate stabilization and continued prosperity. Yet cities were also at the forefront of design and innovation. They contained the technical and creative capacity to deliver the changes in lifestyles, energy usage, political discourse and planning required to deliver truly sustainable development. While cities (and especially coastal cities) might be facing the brunt of climate change, their institutions and inhabitants also held the key to its mitigation.

(UCL Environment Centre and British Embassy Berlin, 2005: 2).

Finally, as health professionals we must be aware that there are two urban worlds emerging. There is the world of the urban wealthy, who experience the health profile of all wealthy people internationally, whether they are born into Asian, African, or American cities. And there is the world of the economically and socially disenfranchised, who work desperately to escape their poverty while risking their lives every day in their homes, on the roads, and in their workplaces. There are many differences between these two worlds, but perhaps the main one lies simply in the numbers: the wealthy urban world is for a tiny minority; the disenfranchised urban world is for the vast majority.

Perhaps the most startling thing about these urban worlds is that they are not separated in space or time. In every city the peoples of these worlds live alongside each other. They breathe the same air and may travel along the same streets. They also have, in essence, the same set of aspirations: to live well and long and to give their children a better future. Our urban future provides us with perhaps the biggest challenge as human beings that we have ever had to face. We have to bring these worlds together and to move them both toward a sustainable future, or there will be no chance of healthy lives for those living in tomorrow’s cities.

There is no easy solution to the challenges of urban health internationally. The majority of the urban world demands, rightly, that their health needs involve meeting their basic rights to clean water, sanitation, adequate housing, education, access to health services, and work that will be safe and remunerative. Interventions toward this would guarantee survival for the urban millions who die unnecessarily today. But alongside this, our urban future needs creative, new solutions too: there are no simple interventions that will address urban violence, for instance. Technical interventions will not address an urban health problem that is rooted in complex social injustice. Obesity and mental health problems also need a new lens. Cities that isolate us from nature and from each other cannot be described as healthy cities for the twenty-first century.

Equity is perhaps the key to the more complex social problems of cities – and it also can lead toward sustainability. A city where all peoples live together in peace, sharing the same spaces and the same resources, is far from today’s urban reality. A city where people think of the next generation and the planet as a whole is also far from this reality. But neither vision is impossible – either to imagine or to achieve. As health professionals we must rise to this challenge and reinvent public health as the urban discipline of the future.

Bibliography:

- African Population Health Research Center (APHRC) (2002) Population and health dynamics in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Nairobi, Africa: African Population and Health Research Center.

- Broughton E (2005) The Bhopal disaster and its aftermath: A review. Environmental Health 4(1): 6.

- Cairncross S and Kinnear J (1992) Elasticity of demand for water in Khartoum, Sudan. Social Science and Medicine 43(2): 183–189.

- Carson C, Hajat S, Armstrong B, and Wilkinson P (2006) Declining vulnerability to temperature-related mortality in London over the 20th century. American Journal of Epidemiology 164(1): 77–84.

- Drucker E, Alcabes P, Bosworth W, and Sckell B (1994) Childhood tuberculosis in the Bronx, New York. The Lancet 343(8911): 1482–1485.

- De Souza ER and de Lima MLC (2006) Panorama da violeˆ ncia urbana no Brasil e suas capitais (The panorama of urban violence in Brazil and its capitals). Cieˆncia y Sau´ de 11(2) available online at: http:// www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=Sci_arttext&pid=s1413-81232006000200014&ing=pt.

- Gawryszewski VP and Costa LS (2005) Social inequality and homicide rates in Sao Paulo City, Brazil (title translated from original). Revista de Sau´ de Pu´ blica 39(2): 191–197.

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, and Waidman TA (1999) Poverty, time, and place: Variation in excess mortality across selected U.S. populations, 1980–1990. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 53(6): 325–334.

- Grupo AfroReggae (2007) Favela Rising. http://favelarising.com/default. php.

- Habitat UN (2006) Meeting Development Goals in Small Urban Centres; Water and Sanitation in the World’s Cities 2006. London: Earthscan.

- Hajat S, Armstrong BG, Gouveia N, and Wilkinson P (2005) Mortality displacement of heat-related deaths: A comparison of Delhi, Sao Paulo, and London. Epidemiology 16(5): 613–620.

- Hardoy JE, Mitlin D, and Satterthwaite D (2001) Environmental Problems in an Urbanizing World: Finding Solutions for Cities in Africa, Asia and Latin America. London: Earthscan.

- Houweling TA, Kunst AE, Moser K, and Mackerbach JP (2006) Rising under-5 mortality in Africa: Who bears the brunt? Tropical Medicine and International Health 11(8): 1218–1227.

- Imparato I (2003) Slum Upgrading and Participation: Lessons from Latin America. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Lee KN (2007) An urbanizing world. In: Sheehan MO (ed.) State of the World 2007: Our Urban Future p. 4. London: Earthscan.

- McCord C and Freeman HP (1990) Excess mortality in Harlem. New England Journal of Medicine 322(3): 173–177.

- Menegat R (2002) Environmental management in Porto Alegre. Environment and Urbanization 14(2): 181–206.

- Montgomery MR, Stren R, Cohen B, and Reed HE (eds.) (2003) Cities Transformed: Demographic Change and Its Implications in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academy Press/ Earthscan.

- Palacios JD and Sara LM (2005) Concertacio´ n (reaching agreement) and planning for sustainable development in Ilo, Peru. In: Bass S (ed.) Reducing Poverty and Sustaining the Environment: The Politics of Local Engagement, pp. 255–279. London: Earthscan.

- Pan American Health Organization (1990) Violence: A growing public health problem in the region. Epidemiological Bulletin 11(2): 1–7.

- Pinheiro PS (1993) Reflections on urban violence. The Urban Age 1(4): 3.

- Pryer J (1993) The impact of adult ill-health on household income and nutrition in Khulna, Bangladesh. Environment and Urbanization 5(2): 35–49.

- Ruel MT and Garrett JL (2004) Features of urban food and nutrition security and considerations for successful urban programming. Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics 1(2): 242–271.

- Satterthwaite D (2007a) The Transition to a Predominantly Urban World and its Underpinnings. London:11ED working paper, 11ED.

- Satterthwaite D (2007b) In pursuit of a healthy urban environment in low and middle-income nations. In: Marcotullio PJ and McGranahan G (eds.) Scaling Urban Environmental Challenges: From Local to Global and Back, pp. 69–105. London: Earthscan.

- Stephens C (1996) Healthy cities or unhealthy islands? The health and social implications of urban inequalities. Environment and Urbanization 7(4): 11–30.

- Stephens C (1999) What has health got to do with it? Using health to guide urban priority-setting processes towards equity. In: Davila J and Atkinson A (eds.) Environmental Management in Metropolitan Areas, pp. 88–95. London: University College London Press.

- Stephens C and Stair P (2007) Charting a new course for urban public health. In: Sheehan MO (ed.) State of the World 2007: Our Urban Future, pp. 134–148. Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute. University College London (UCL) Environment Centre and British

- Embassy Berlin (2005) Climate Change and Urban Areas, Workshop at University College London. London, UK 11–12 April. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/environment-institute/pdfs/ workshop_climate_change.pdf (accessed February 2008).

- UNICEF (2000) Progotir Pathey; On the Road to Progress; Achieving the Goals for Children in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF.

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD) (2006) World Urbanization Prospects: The 2005 Revision Population Database. New York: UNPD.

- Vermelho LL and de Mello Jorge MHP (1996) Mortalidade de jovens: Ana´ lise do perı´odo de 1930 a 1991 (a transic¸ a˜ o epidemiolo´ gica para a violeˆ ncia) (Youth mortality: 1930–1991 period analysis [the epidemiological transition to violence]). Revista de Sau´ de Pu´ blica 30(4):11.

- Wilson M and Daly M (1997) Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighbourhoods. British Medical Journal 314(7089): 1271–1274.

- http://www.alliance_healthycities.com/index.html – Alliance for Healthy Cities.

- http://eau.sagepub.com – Environment and Urbanization.

- http://www.paho.org/English/ad/sde/espacios.htm – Healthy Municipalities and Urban Health in Latin America.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.