This sample Violence Epidemiology and Overview Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

This research paper provides an overview of the public health approach to violence and its prevention. This approach has emerged over the last three decades, and has been consolidated in the last decade by the forty-ninth World Health Assembly declaring violence a priority in 1996, the publication of the World Report on Violence and Health by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002, the publication of subsequent strategic and policy guidance documents detailing how to implement and evaluate violence prevention initiatives, and the ongoing Global Campaign for Violence Prevention coordinated by WHO. While evidence of successful interventions to prevent violence remains incomplete, for every form of violence there is now some evidence of strategies that have been effective and could be scaled up, given political will and investment.

Three key themes emerge from the public-health focused research on violence over this period. Firstly, violence is common, estimated to be responsible for 1.6 million deaths per year globally and substantially more physical, psychological, and social morbidity. Secondly, violence is not random, but like other forms of injury can be predicted to some extent by demographic and situational factors. The risk factors for violence are relatively well known, and those who have experienced one form of violence are more likely to experience another. Thirdly, violence is relational: The majority of violent incidents occur between people who know one another. Violence can be a means for one person or group to demonstrate their power over another. In this research paper, I will explore these themes in more detail, providing a framework for a public health approach to understanding violence.

Definitions

Public health practitioners generally define violence in broad terms. The World Health Organization defines violence as:

the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation. (Krug et al., 2002)

This definition states that the use of physical force or power must be intentional in order for a violent act to have occurred. Intentionality is usually clear to the victim but many injuries that are intentional may be reported as unintentional. For example, a victim of domestic violence presenting to a hospital department with a violent partner is unlikely to voluntarily disclose that an injury was intentionally caused. An intentionally inflicted injury on a sports field may be difficult to differentiate from an accidental sports injury.

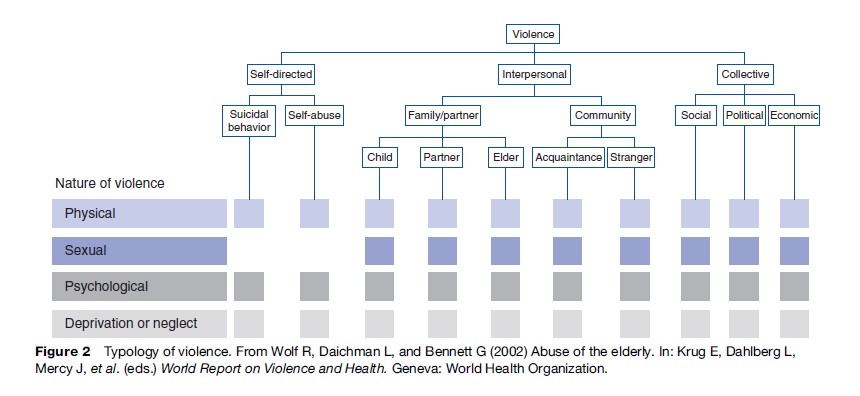

WHO’s definition is further expanded in their typology of violence, which classifies violence according to its nature and against whom it is directed (Figure 2).

As part of this typology, violence is classified as self-directed, interpersonal, or collective. Much work in violence prevention is aimed at interpersonal violence. Many forms of violence occur simultaneously; for example, rape may be used as a weapon of war, and victims of childhood abuse are more likely to be both self-harming and violent toward others in later life.

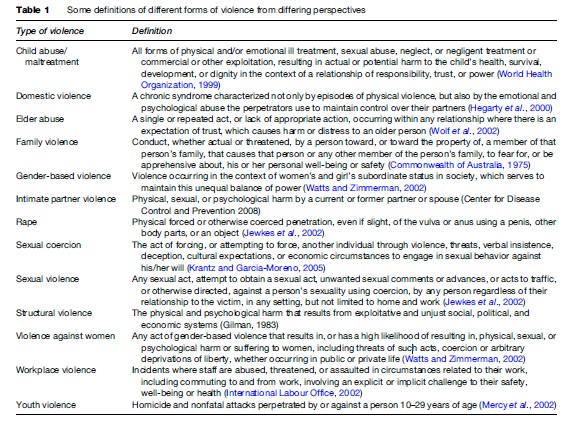

Definitions vary according to their purpose, whether they are primarily to be applied for research, policy, legislative, or advocacy purposes. Defining violence broadly allows an examination of the range of risk and protective factors that influence violent outcomes, in particular those factors that are common across different types of violence and in different settings. Legal definitions, such as those of sexual assault or rape, are in general more narrow and specific, given the implications for the perpetrators if convicted. Defining violence in different ways has consequences for the victim, the perpetrator, the legal and health-care systems, and society more broadly. In some cases, definitions of violence are highly contentious, for example in relation to terrorism. Examples of definitions of different forms of violence from differing perspectives are provided in Table 1.

The use of the term victim is also not universal: Some prefer to speak of survivors of violence, recognizing the resilience and agency associated with recovering from a history of abuse or violence.

Injury is generally taken to mean organic harm to a person’s body caused by acute exposure to energy. However, a significant amount of the harm from violent injury is sustained through psychological damage. Therefore the definition of intentional injury may differ from that of violence, although often the two are used interchangeably.

In general, narrow definitions of violence involve physical acts, whereas broader definitions also encompass neglect and/or psychological harm. This is a critical point: It is much easier to understand, analyze, and develop public health interventions for injuries that can be physically identified. Psychological damage is more pervasive and the interventions required need greater input from other sectors. However, as anthropologists Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois remind us:

Violence can never be understood solely in terms of its physicality – force, assault, or the infliction of pain – alone. Violence also includes assaults on the personhood, dignity, sense of worth or value of the victim. The social and cultural dimensions of violence are what give violence its power and meaning. (Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois, 2004)

Measurement Of Violence

To understand the burden of violence, we need to accurately measure its incidence and prevalence, impacts on health, economic costs, and modifiable risk factors. Data about violence are collected through both routine administrative data sources and specially designed epidemiological studies. Routine data sources include death certificates; coroners’ or mortuary reports; ambulance, hospital, and clinic records; occasions of service from other responding agencies; police records; and court records. These may be the only form of information available in many circumstances. Routinely collected data are a relatively inexpensive method of identifying trends and patterns of violence over time. It may be of particular value to identify subgroups at risk, whether as a result of age, gender, ethnicity, religious, geographic, or class background. However, violence is known to be seriously underreported to any public agency. Accurate prevalence data require denominator data, i.e., information on the population at risk of violence. Representative cross-sectional surveys taken from populations provide the best information on violence incidence and/or prevalence, and are collected anonymously, which facilitates reporting. Victimization surveys ask specific questions about experience of violence within a defined population (e.g., women in one particular area), within a specified time frame (e.g., a lifetime, the last 12 months), and from particular sources (e.g., an intimate partner, a stranger). Perpetration surveys identify whether or not the person surveyed has committed a violent act, again within specified parameters, but these types of surveys are rare. Cross-sectional surveys are relatively costly compared to routine surveillance and need to take into account the safety, security, and confidentiality of participants.

Surveillance is the ongoing systematic collection, collation, and analysis of data and the prompt dissemination of the resulting information to those who need to know so that an action can result. The surveillance of violence can therefore include both routinely collected data and periodic surveys, particularly those conducted in a standardized format so they can be compared by time and place. An ideal surveillance system meets a number of criteria, including that it is simple to use, acceptable to users, stable over time, sensitive to changes in incidence, and contains valid data. The most internationally comparable data about violence are obtained when the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes are used for classifying and recording data collected through administrative data sets, such as death registries and inpatient statistics. ICD codes are periodically updated by WHO. The latest edition, ICD-10, uses body region as the primary axis for classification, with type of injury as a secondary axis. External causes of injury and poisoning (known as E codes) classify how the injury happened, whether or not the injury was intentional or accidental, the place where the event occurred, and the activity of the person at the time of the injury. There are currently efforts underway to develop more detailed classification systems for injury, including violence, such as the International Classification of External Causes of Injury (ICECI) codes. ICECI is intended to complement the ICD external causes codes, and contains core data items and additional modules. A specific module on violence has been developed.

Different countries and settings have very different levels of surveillance for violent incidents. Even in the wealthiest nations, the surveillance of violence is patchy and incomplete, and often does not provide data that can be acted upon in a timely fashion. WHO sets priorities for countries to consider in their data collection relevant to violence. These are, in order of priority: Fatal violence, nonfatal incidents, socioeconomic risk factors, and behavioral risk factors. For example, in situations of conflict or displacement, it may be a priority to collect some basic data on all people seen by health or police agencies with nonfatal injuries rather than implement more sophisticated surveillance systems.

Communities at greater risk of violence can be identified through area-wide analysis of national data sets such as census data or studies of risk factors that vary by area, such as drug and alcohol use, concentration of alcohol outlets, socioeconomic status, and unemployment. For example, analysis of Australian data reveals much higher levels of violence in some areas with high Aboriginal populations. Much of this difference can be explained by the concentration of risk factors in some communities, including low socioeconomic status, high unemployment, high numbers of young people, high levels of risky alcohol consumption, real and perceived racism and discrimination, and poor access to services.

Epidemiology And Risk Factors

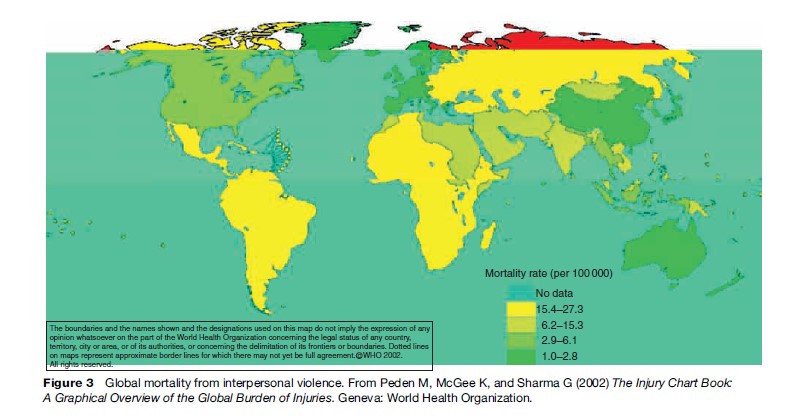

Worldwide, on any one day approximately 4500 people will die a violent death: Half of these will be from self-inflicted injuries, one-third will be murdered, and one fifth killed in war. Approximately 90% of these people will live in a low or middle-income country. Mortality rates from violence vary significantly between countries, with the highest rates in the WHO region of the Americas. Figure 3 graphically displays global mortality from interpersonal violence.

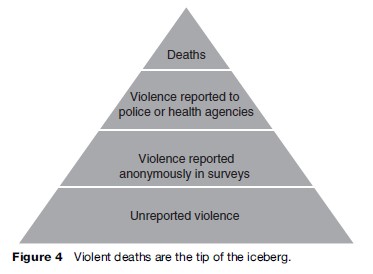

It is more difficult to obtain comparative data on morbidity secondary to violence, for the reasons discussed in the preceding section. Violent deaths are the tip of the iceberg, with physical and psychological injuries much more common (Figure 4). Given both the estimated lifetime prevalence of some forms of violence, for example that 10–50% of women experience physical violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime, and the significant barriers to reporting, the burden of illness is likely to be underreported and underestimated in most settings.

Different types of violence have different risk and protective factors, that is, those factors that can be analyzed to make inferences about populations at risk, and where interventions are possible. There are some risk and protective factors that are common to a number of different manifestations of violent behavior. Risk factors include alcohol abuse, access to firearms, neighborhood concentrations of poverty, and social norms that support violence. Protective factors include supportive and stable parenting, successful completion of education, social and gender equality, and strong police and judicial systems.

Age And Gender

Age determines risk of different forms of violence. Children and old people are most vulnerable to neglect, and young children to physical abuse. People of all ages and both sexes may be subject to emotional abuse. Girls of reproductive age are especially vulnerable to sexual abuse and trafficking. Women are also more vulnerable to violence during pregnancy.

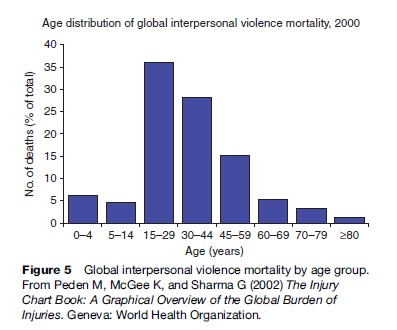

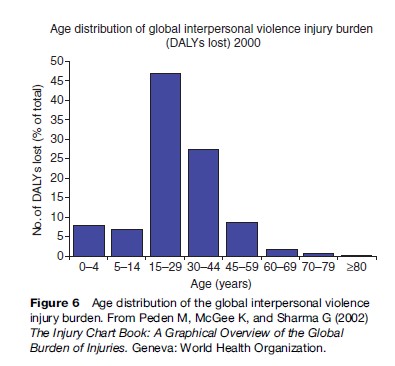

Being a young adult male is the most significant risk factor for being both a victim and perpetrator of violence, according to the methodology used by the WHO Global Burden of Disease Study. The 15to 29-year age group is most at risk. Figure 5 demonstrates global interpersonal violence mortality by age group, and Figure 6 the burden of injury attributable to interpersonal violence by age group. Men make up the majority of this burden of injury.

This pattern has been shown around the world in many different settings.

Men are more likely to be the direct victims of war, as male combatants, and to be involved in gang and street violence. Women are the predominant victims of intimate partner violence and sexual violence, and are generally more likely to be assaulted in their own homes than in public places.

Alcohol And Drug Use

It is well known that there is a strong association between alcohol use and violence, and alcohol use is a risk factor for suicide, sexual violence, intimate partner violence, and youth violence. However, there has been much debate about whether alcohol actually causes violent behavior. It is likely that it is not just the pharmacological properties of alcohol per se, but the context in which alcohol is being used that leads to violent outcomes. Individual responses to alcohol are modified by a range of variables including age, genetics, and personality characteristics. Police and emergency department staff are well aware that violent incidents are more common in times of peak alcohol use, such as weekend evenings.

There is no direct link between drug use in general and violence, although recent research is investigating the relationship between aggression and methamfetamine use. The environment surrounding drug trafficking and distribution is linked to violence. Some drugs, including alcohol, are used to facilitate sexual assault.

Socioeconomic Status

Although violence is known in every society and every setting, around the world those most likely to be a victim of violence are those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged or living in poverty. Maps of violence victimization by areas of deprivation in developed countries show consistent results: Violence is geographically concentrated in poorer areas. It is also concentrated in areas with low social cohesion and high residential mobility. Given the higher prevalence among young people, violence is also more likely in communities with a high proportion of young people, or a youth bulge.

Access To Firearms

Having access to firearms is an important factor in violent outcomes. Approximately 200 000 people are killed annually by firearms in nonconflict situations, and approximately 300 000 in armed conflicts. In the United States, citizens are given the right to own firearms: The United States has the highest rate of firearm-associated deaths of all developed countries. The availability of firearms increases the risks of both intentional (suicide and homicide) and accidental firearm injuries and deaths. Small arms are accessible, widely distributed, and available at relatively low cost in many countries. They play a major role in internal conflicts. Those with access to small arms may use them to terrorize or exploit local communities.

Health Consequences

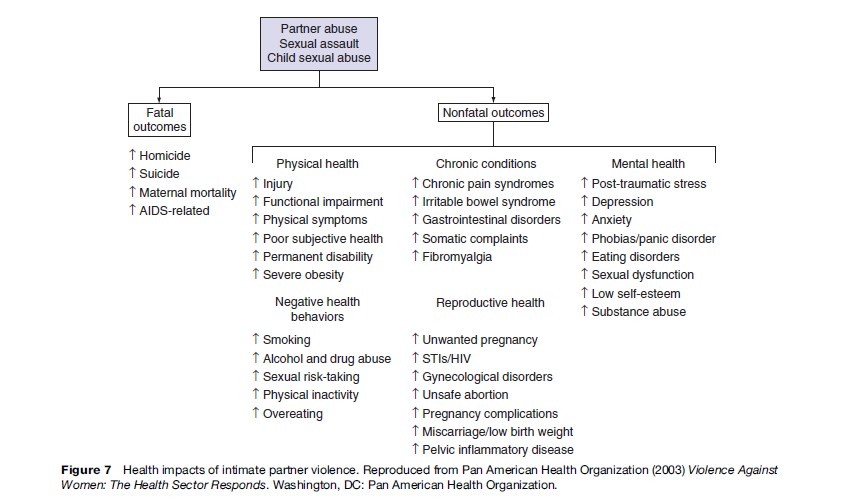

The health consequences of violence are both physical and psychological. The severity and consequences of physical injuries depend upon the amount of force inflicted and access to medical care. Common injuries seen after physical assault are gunshot and knife wounds, fractures, lacerations, and bruising. Psychological injuries after physical abuse depend upon the relationship between the victim and perpetrator, the situation in which the violence occurs and the actions taken after the incident. Longer-term psychological abuse can lead to mental health problems, drug and alcohol abuse, physical illnesses, and an increase in self-harming behaviors. As an example, the health impacts of intimate partner violence are summarized in Figure 7. A recent Australian study estimated that intimate partner violence was responsible for more ill health and premature death in women under 45 years than any one of the other well-known risk factors, including high blood pressure, obesity, and smoking.

Exposure to violence in childhood is strongly linked to adverse outcomes in children’s development. Adults who were maltreated as children have higher rates of risk-taking behavior (e.g., smoking, alcohol and drug use, high-risk sexual behaviors) and consequently higher rates of ischemic heart disease, chronic lung disease, sexually transmitted diseases, and cancer.

Collective violence can result in death, physical injuries and disability, increased sexual violence, increased mental health problems, and indirect effects such as increased communicable diseases, poorer reproductive health outcomes, and malnutrition. There are also multiple effects on the determinants of health as well as on health services.

Ecological Model

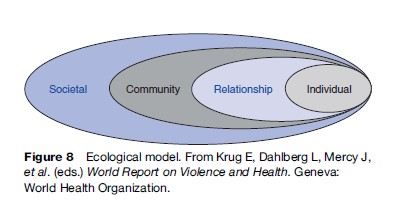

The ecological model has been used extensively in the public health field. In relation to violence, the ecological model allows one to look at the different levels that may increase or decrease the chance of a violent outcome for an individual or community. At an individual level, for example, a person with poor impulse control or with a personal history of abuse is more likely to be engaged in a violent incident. But they may be protected by a supportive and engaged family. They may live in a community where violence is part of the social fabric, which again increases their risk of being involved in a violent incident. But there may be successful firearm restrictions in place at the societal level that reduce the chance of a fatal outcome from a particular violent incident. Factors can be modified at any of these levels – individual, family, community, and society – to prevent violence. Interventions at a number of levels are likely to be most effective. Sethi et al. detail risk factors and preventive strategies at each level of the ecological model in more detail. Individual articles describe how to apply this model to specific forms of interpersonal violence (Figure 8).

Public Health Responses

Public health responses to violence include measuring and documenting its prevalence and impact; designing, implementing and evaluating preventive strategies; collaborating with other agencies and sectors to enable multidisciplinary engagement and action; and advocating with politicians and others for violence to be understood as an important, preventable public health issue. Leadership in this arena is critical. It is also important for public health practitioners to define where their remit starts and ends; what forms of violence are most amenable to public health methods; and, critically, how to do more good than harm.

Public health prevention can be generally divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary strategies. Primary prevention methods aim to prevent violence before an incident; secondary prevention either to reduce the harm and mitigate the effects of an incident or reduce the risks of harm in a high-risk population; and tertiary prevention to rehabilitate and reintegrate victims and perpetrators of violence. Interventions can be directed universally or at individuals or groups at heightened risk of violence. The ecological model provides a useful framework around which interventions can be planned and implemented.

Conclusion

Violence is common and responsible for a significant amount of the global burden of disease and mortality. To some extent it is preventable, and public health practitioners are increasingly part of a global effort to decrease its impact. The ecological model is a useful framework for understanding the complex interplay of individual, family, community, and societal factors that leads to violent outcomes. Looking upstream to the determinants of violent behavior rather than simply criminalizing perpetrators is an important component of the public health approach to disease prevention.

Bibliography:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008) Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Scientific Information: Definitions. http://www. cdc.gov/ncipc/dvp/IPV-definitions.htm (accessed April, 2008).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Family Law Act 1975, S60(D).

- Gilman R (1983) Structural Violence. In Context: A Quarterly Journal of Humane Sustainable Culture 4: 8.

- Hegarty K, Hindmarsh ED, and Gilles MT (2000) Domestic violence in Australia: Definition, prevalence and nature of presentation in clinical practice. The Medical Journal of Australia 173: 363–367.

- International Labour Office/International Council of Nurses/WorldHealth Organization/Public Services International (2002) Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

- Jewkes R, Sen P, and Garcia-Moreno C (2002) Sexual Violence. In: Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, et al. (eds.) (2002) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Krantz G and Garcia-Moreno C (2005) Violence against women. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59: 818–821.

- Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, et al. (eds.) (2002) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Lievore D (2003) Non-reporting and Hidden Recording of Sexual Assault: An International Literature Review. Canberra, Australia: Office for the Status of Women Commonwealth of Australia.

- Macdonald S, Cherpitel CJ, Borges G, De Souza A, Giesbrecht N, and Stockwell T (2005) The criteria for causation of alcohol in violent injuries based on emergency room data from six countries. Addictive Behaviors 30: 103–113.

- Mercy JA, Butchart A, Farrington D, and Cerda´ M (2002) Youth violence. In: Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, et al. (eds.) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Miles-Doan R and Kelly S (1997) Geographic concentration of violence between intimate partners. Public Health Reports 112: 135–141.

- Pan American Health Organization (2003) Violence Against Women: The Health Sector Responds. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization.

- Peden M, McGee K, and Sharma G (2002) The Injury Chart Book: A Graphical Overview of the Global Burden of Injuries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, and Earls F (1998) Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277: 918–924.

- Scheper-Hughes N and Bourgois P (eds.) (2004) Violence in War and Peace. An Anthology. Oxford, UK: Carlton Blackwell Publishing.

- Sethi D, Habibula S, McGee K, et al. (eds.) (2004) Guidelines for Conducting Community Surveys on Injuries and Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- VicHealth (2004) The Health Costs of Violence: Measuring the Burden of Intimate Partner Violence. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Health Promotion Association.

- Watts C and Zimmerman C (2002) Violence against women: Global scope and magnitude. Lancet 359: 1232–1237.

- Wolf R, Daichman L, and Bennett G (2002) Abuse of the elderly. In: Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, et al. (eds.) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO/FIC (2004) International Classification of External Causes of Injuries (ICECI), version 1.2. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Consumer Safety Institute.

- World Health Organization (1999) Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention, 29–31 March, 1999. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Doll LS, Bonzol SE, Mercy JA, and Haas EN (eds.) (2006) Handbook of Injury and Violence Prevention. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, and Lozano R (eds.) (2002) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Pinheiro P (2006) Rights of the Child: Report of the Independent Expert for the United Nations Study on Violence Against Children. United Nations General Assembly. New York: United Nations.

- Prothrow-Stith D, Spivak H, and Sege RD (2002) Interpersonal violence prevention: A recent public health mandate. In: Detels R, McEwen J, Beaglehole R, and Tanaka H (eds.) Oxford Textbook of Public Health, 4th edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Rutherford A, Zwi AB, Grove NJ, and Butchart A (2007) Violence: A glossary. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61: 676–680.

- Rutherford A, Zwi AB, Grove NJ, and Butchart A (2007) Violence: A priority for public health? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61: 764–770.

- Waters H, Hyder A, and Rajkotia Y (2004) The Economic Dimensions of Interpersonal Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Injuries and Violence Prevention, World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization and International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (2006) Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Zahn M, Brownstein H, and Jackson S (2004) Violence: From Theory to Research. Newark, NJ: Anderson Publishing Company.

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/dvp/dvp.htm – US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Violence Prevention.

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/specials/1416_violence/index.shtml – Violence Begins At Home, BBC World Service.

- http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/en/ – World Health Organization, Department of Violence and Injury Prevention.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.