This sample Yaws, Pinta, And Endemic Syphilis Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Yaws, pinta, and endemic syphilis (bejel) are all grouped together as nonvenereal endemic treponematoses, which are chronic bacterial infections caused by treponemes. These are mostly prevalent among communities living in poor, unhygienic conditions in hot and humid areas. Although seldom fatal, the treponematoses cause public health, social, and economic problems in marginalized populations living in remote, difficult-to-reach hilly and tribal areas because of morbidity and disability associated with the disease. In the landmass between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, these infections constitute a public health problem.

Nonvenereal treponematoses are distinguished from venereal syphilis on the basis of clinical and epidemiological features because the treponemes that cause these diseases have identical morphology. Pinta involves the skin alone; yaws affects skin and bones; and endemic syphilis involves the skin, bone, and mucous membranes. Each disease tends to progress by stages, but these stages are neither distinct nor as predictable as in syphilis. Congenital infection as well as cardiovascular and central nervous system involvement occur rarely, if ever, in these infections but are common in venereal syphilis.

With the availability of penicillin – the magic bullet for the treatment of nonvenereal treponematoses – the fight against endemic treponematoses has been a priority for the World Health Organization (WHO) since its creation in 1948. In the period 1952–64, the WHO, in close collaboration with UNICEF, launched the Global Endemic Treponematoses Control Programme (TCP), which became an unusually successful public health campaign. Over 160 million people were examined and approximately 50 million patients, contacts, and latents were treated in 46 countries, reducing the overall prevalence of these diseases by more than 95%. The prevalence of active yaws lesions was reduced from over 20% to less than 1% in many rural areas. In Bosnia, endemic syphilis was eradicated, the only example of eradication of an endemic treponematosis. Some scattered endemic foci of endemic syphilis in central Asia, Australia, and India were treated and eliminated by penicillin treatment campaigns in the 1950s.

The control strategy subsequently changed from a vertical program to one integrated into the basic health services. These basic health services were to cope with the remaining last cases of endemic treponematoses in the community until eradication has been achieved. Because of relaxation of active surveillance activities after the mass campaigns, the goal of eradication was not attained and a number of foci of transmission remained. By the end of the 1970s, a resurgence of the endemic treponematoses had occurred in many areas of the world. The necessity for renewed efforts was recognized by the World Health Assembly and expressed in WHA Resolution 31.58. Since 1984, a global conference in Washington, DC, three major regional meetings, and partners’ meetings have brought the problem of endemic treponematoses to the attention of health policy makers and the international donor community. This resulted in renewed control efforts in a number of countries. WHO’s South East Asia Region has set the target of yaws eradication and efforts are going on in this direction. In a meeting organized by the WHO Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) at its Headquarters in Geneva in January 2007, the launch of a new global initiative to address the problem of persistence and resurgence of yaws was discussed.

Causative Agent

Treponema pallidum, the causative organism of syphilis, was discovered in 1905 by Fritz Schaudinn and in the same year Castellani discovered its subspecies pertenue, the causative organism of yaws. Yaws and pinta are caused by treponemes, which are conventionally designated as a unique species (Treponema pertenue causes yaws and T. carateum pinta), but no significant morphologic or genetic differences have been demonstrated among T. pertenue, T. carateum, and T. pallidum. The etiological agents of endemic syphilis and yaws are generally held to be identical with T. pallidum and have been designated as T. pallidum ssp. endemicum and ssp. pertenue, respectively. Pinta is caused by T. carateum. Infection with one treponema provides partial protection against the other, which indicates that they share common antigens. There is no laboratory test that can distinguish these treponemes from one another.

Because of small size and mass of treponemes, they cannot be seen with an ordinary microscope unless a dark-field condenser is used. Their characteristics include the following:

- They look like thin, silver threads coiled like a corkscrew approximately 3–18 mm long having 8–20 spirals. They stain very poorly because their thickness approaches the resolution of the light microscope.

- They are motile with a characteristic rapid spinning motion.

- The organisms are delicate, requiring pH between 7.2 and 7.4, temperatures in the range 30ºC to 37ºC and a microaerophilic environment.

- The structure of these organisms is somewhat different: The cells have a coating of glycosamine-glycans, which may be host-derived, and the outer membrane covers the three flagella that provide motility.

- In addition, the cells have a high lipid content (cardiolipin, cholesterol), which is unusual for most bacteria. Cardiolipin elicits Wassermann antibodies that are diagnostic for syphilis.

- Treponema possesses a complex antigenic makeup that is difficult to determine because the organisms cannot be grown in vitro.

It is unclear whether the clinical and epidemiological differences among yaws, pinta, endemic syphilis, and venereal syphilis are solely determined by environmental and host factors or are attributable to undefined biological differences among the causal treponemes.

Humans are their natural host. Treponemal antibodies are demonstrable in some proportion of nonhuman primates in regions of Africa where human yaws and endemic syphilis are common, and pathogenic treponemes have been found in skin lesions and lymph nodes of seropositive animals. These treponemes have produced yaws-like lesions in susceptible monkeys and hamsters.

Epidemiology

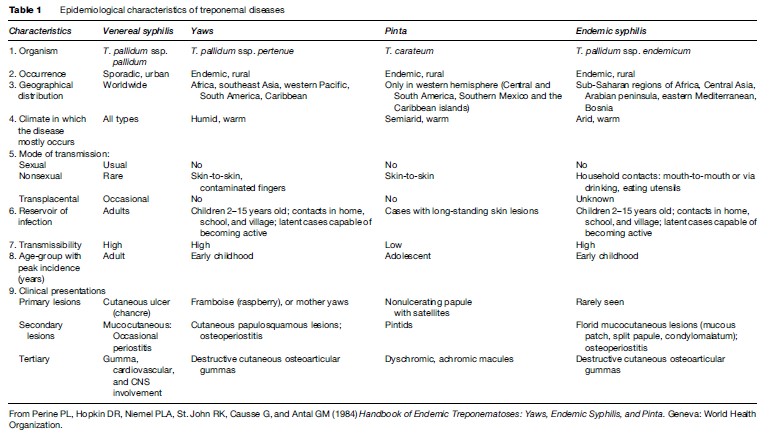

Epidemiological characteristics of treponemal diseases are summarized in Table 1.

Mode Of Transmission

Yaws and endemic syphilis are diseases of young children. Scanty clothing, poor hygiene, and frequent skin trauma favor transmission of yaws among children. Spread occurs by direct contact with infected lesions and perhaps by passive transfer of treponemes by insects. Transmission through fomites is insignificant. Skin-to-skin transmission is less important in endemic syphilis than in yaws; instead, infection of mucous membranes results from direct mouth-to-mouth contact or from contaminated fomites, such as shared drinking or eating utensils.

Pinta occurs only in the Western hemisphere, with onset at the age of 10–20 years of age. It is not very contagious and its mode of transmission is not well defined.

Present Status

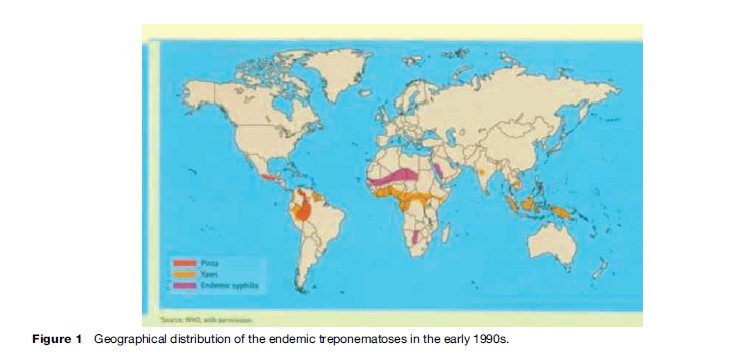

There is no regular system for reporting of nonvenereal treponematoses. The information summarized here is based on published reports and is shown in Figure 1. Ivory Coast, Congo, Ghana, Togo, and Benin have large reservoirs of yaws and account for over 90% of cases reported to the WHO since 1982. North of these countries, the Sahel nations of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Senegal have prevalence rates in some areas of 10–15% for endemic syphilis. Seroactivity and late manifestations of endemic syphilis continue to occur among nomads in Saudi Arabia. Attenuated or asymptomatic infection has been observed.

In the Americas, foci of yaws persist in Haiti; Dominica, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent; Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador; a few areas of Brazil; and Guyana and Surinam. Pinta is confined to Central America and northern South America, where it appears to have regressed to remote Indian villages. Its prevalence today is probably less than 1% of that found 20 years ago.

In Southeast Asia, active yaws cases were reported from only two countries in 2006: Indonesia and Timor Leste. India declared achievement of yaws elimination in 2006. Yaws elimination was defined as no reporting of new early cases supported by laboratory investigations and on the basis of good-quality search in all endemic areas of the country with validation by independent appraisal.

Biologic Relationships

Specific humoral antibodies to T.pallidum are produced in individuals with yaws, pinta, or endemic syphilis, but the time of appearance of antibodies after onset of infections is variable. The fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, the T. pallidum hemagglutination test (TPHA), and the T. pallidum immobilization (TPI) test cannot differentiate the treponematoses.

Individuals who have had yaws or pinta are considered relatively immune to syphilis, and persons with active pinta or syphilis cannot be superinfected with T. pallidum ssp. pertenue by experimental inoculation.

Clinical Manifestations

Yaws

In areas where yaws has long been endemic, there are synonyms for it in local languages. Of approximately 80 terms, some of its synonyms are pian (French), framboesia (Dutch/German), buba (Spanish), bouba (Portuguese), parangi (Sri Lanka), coco (Fiji island), and dube (Gold Coast). The term yaws is thought to be of Caribbean origin. In the language of the Caribs India people, yaya was a word for sore.

The incubation period is 3–4 weeks.

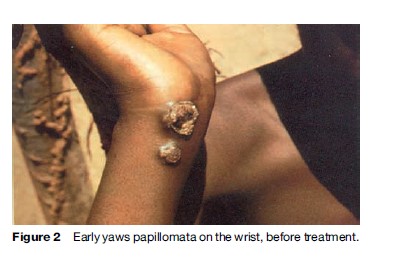

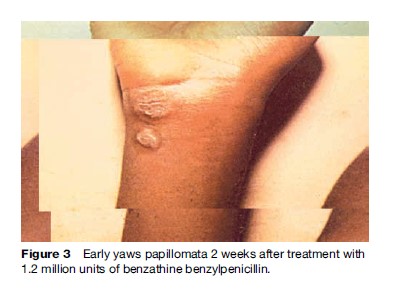

Yaws produces a great variety of skin, bone, and joint lesions (Figures 2–5) and has been categorized as early and late yaws lesions. Early lesions are usually infectious and occur in the first 5 years of illness. These heal slowly, leaving a scar, hyperpigmentation, or depigmentation. In contrast, late lesions are not infectious and occur in about 10% of cases, starting 5 years or more after infection. A thin yellow crust of serous exudates teeming with T. pertenue covers the initial early lesions. The yaws lesions have a number of common characteristics:

- Early lesions are often pruritic, and scratching facilitates both spread of the infection to other areas of the body by autoinoculation and the transmission of the disease within the community.

- The early lesions tend to occur in crops, which often overlap with one another.

- Mixed (polymorphous) forms of lesions are often present in the same patient.

- A change in climate may influence the number and morphology of yaws lesions. In the dry season, fewer lesions are present and they tend to be of the macular type; papillomata tend to retreat to the more humid areas of the body surface such as axilla and anal folds.

- Erythema and induration do not occur in early yaws lesions.

- Painful papilloma on the soles of the feet result in a crab-like gait referred to as crab yaws.

- Histologic findings in early lesions are mononuclearcell infiltration, acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and the presence of many treponemes, while late lesions show endarteritis.

Constitutional symptoms such as fever and malaise are not significant in yaws. The lymph nodes draining cutaneous lesions are frequently enlarged and tender, but they do not suppurate. Nocturnal bone pain and tenderness of the tibial shaft and other long bones due to periostitis are common in early yaws.

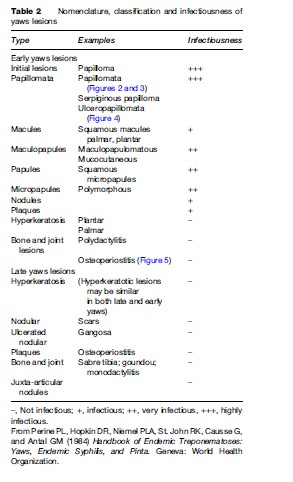

The nomenclature, classification, and infectiousness of yaws lesions are given in Table 2. Despite the variety of yaws lesions, in endemic areas the disease can usually be accurately diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings alone. It becomes less reliable in the areas where prevalence has decreased, necessitating the use of easily performed serologic tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) card test. T. pertenue can be demonstrated by darkfield examination in early cutaneous lesions but should not be confused with other spirochetes found in tropical ulcers. TPHA and FTA-ABS tests are more specific.

Pinta

Pinta is also known as mal de pinto (in Mexico), carate (in Colombia and Venezuela), azul (in Chile and Peru) or purupuru.

The usual incubation period is 2–3 weeks.

The initial lesion of pinta is a small papule or an erythematosquamous plaque located most often on the uncovered part of the body, usually the extremities, the dorsum of the foot, or the back of the hand. The papule (or plaque) enlarges slowly by local extension or by merging with satellite lesions to form a hyperkeratotic, pigmented lesion accompanied by an enlargement of the lymph nodes draining the lesion. Disseminated lesions identical to the initial lesions develop 3–9 months after infection. These pintids vary in number and location. They may slowly enlarge and merge to reach a diameter of 7–25 mm. The lesions become pigmented with age, changing slowly from a copper color to lead-gray to slate-blue as a result of photosensitization. Late pinta is characterized by pigmentary changes, from dyschromic treponeme-containing lesions to achromic treponemefree lesions. This depigmentation process occurs at different rates even within the same lesion, giving rise to different degrees of hypochromia and atrophy around dyschromic and achromic lesions.

Pinta does not involve osseous tissue or viscera and causes no disability or complication other than that associated with cosmetic disfigurement (leukoderma).

Histologically, there is deposition of pigment in the dermis with decreased melanin pigment in the basal cell layer.

Reaginic and antitreponemal antibody tests are positive, but may take four times longer to become positive in pinta than in venereal syphilis.

Endemic Syphilis

Synonyms for endemic syphilis are bejel (Arabic), njovera, dichuchwa (in Zimbabwe), endemic syphilis of Bosnia, and nonvenereal or childhood syphilis. Extinct forms of the disease are believed to include the sibbens of Scotland in the seventeenth century, the radesyge of Norway in the eighteenth century, and the skerljevo of the Croatian coast in the nineteenth century.

A primary cutaneous lesion is rarely seen in endemic syphilis and when present is extragenital. The earliest manifestation is usually a mucous patch on the oropharyngeal mucosa, which may be followed by a variety of secondary-type rashes or lesions. The latter prefer moist body surfaces such as the axillary and genital areas. Periostitis is common. Regional lymphadenopathy occurs. After a variable latent period, most patients develop late lesions such as osseous or cutaneous gummas. Destructive gumma, osteitis, and gangosa are more common than in late yaws. Gumma occurs on the nipples of mothers who have themselves previously had endemic syphilis and who breastfeed infants with oral lesions. Both early and late forms of endemic syphilis may coexist in the same family. The tertiary lesions of endemic syphilis sometimes may be a consequence of repeated exposure of a previously sensitized host to reinfection.

Endemic syphilis differs from congenital syphilis in that dental change, interstitial keratitis, and neurosyphilis rarely, if ever, occur. Cardiovascular complications are considered rare in both endemic and congenital syphilis.

Treatment

Treatment is similar for all the endemic treponematoses. A single intramuscular injection of 1.2 million units of benzathine penicillin in adults and half this dose in children under 10 years results in rapid resolution of lesions and prevents recurrence. In persons who are allergic to penicillin, oral tetracycline hydrochloride in adults and erythromycin in children (<8 years), pregnant and lactating mothers is recommended for a period of 15 days in four divided doses.

Prevention And Control

The following measures are applied to prevent the nonvenereal treponematoses:

- General health promotion measures: Health education of the public about the value of better sanitation, including liberal use of soap and water and the importance of improving social and economic conditions over a period of years to reduce the incidence. Improve access to health services.

- Organize intensive control activities on a community level suitable to the local problem; examine the entire population, and treat patients with active or latent disease. Treatment of asymptomatic contacts is beneficial, and WHO recommends treating the entire population when the prevalence rate for active disease is above 10% (total mass treatment); if prevalence is 5–10%, treat patients, contacts and all children below 15 (juvenile mass treatment); if less than 5%, treat active cases plus household and other contacts (selective mass treatment). Periodic clinical resurveys and continuous surveillance are essential for success.

- Serological surveys for latent cases, particularly in children, to prevent relapses and development of infective lesions that maintain the disease in the community.

- Provide facilities for early diagnosis and treatment as part of a plan in which selective epidemiological control campaigns are eventually consolidated into permanent local health services.

- Treat disfiguring and incapacitating late manifestations.

Yaws Eradication

Yaws is amenable to eradication because humans are the only reservoir of infection, the distribution of the disease is focalized, thus allowing targeted interventions, the causative organism is sensitive to penicillin and the available drug, benzathine penicillin, is safe, stable, inexpensive, and effective in a single administration.

Learning from the success of smallpox eradication, experts suggest that the strategy for yaws eradication should emphasize ongoing active surveillance, investigation of outbreaks, and the treatment of active cases and their contacts rather than mass treatment.

Bibliography:

- Anonymous (2004) Treponematoses Including Yaws: Report of an Intercountry Workshop, Jakarta, Indonesia, 14–16 December 2004. New Delhi, India: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia.

- Anonymous (2006) Proceedings of Intercountry Workshop on Yaws Eradication in South East Asia Region, Bali, Indonesia, 19–21 July 2006. New Delhi, India: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia.

- Bora D, Dhariwal AC, and Lal S (2005) Yaws and its eradication in India: A brief review. Journal of Communicable Diseases 37(1): 1–11.

- Burke JP, Hopkins DR, Hune JC, Perire P, and St. John R (eds.) (1985) International symposium on yaws and other endemic treponematoses. Reviews of Infectious Diseases, 7: S217–S351.

- Henderson DA (1999) Eradication: Lessons from the past. Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report 48 (supplement): 16–22.

- Heymann DL (2004) Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

- Hopkin DR (1977) Yaws in Americas, 1950–1975. Journal of Infectious Diseases 136: 548.

- Lal S, Jain DC, Dhariwal AC, and Bora D (2006) Yaws Elimination in India-A Step Towards Eradication. New Delhi, India: National Institute of Communicable Diseases, Delhi and World Health Organization Country Office for India. www.whoindia.org (accessed January 2008).

- Perine PL, Hopkin DR, Niemel PLA, St. John RK, Causse G, and Antal GM (1984) Handbook of Endemic Treponematoses: Yaws, Endemic Syphilis, and Pinta. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Sehgal PN, Banerjee KB, and Narain JP (1987) Yaws: Prospects and Strategies for Eradication in India. Delhi, India: National Institute of Communicable Diseases.

- Tharmaphornpilas P, Srivanichakorn S, and Phraesrisakul N (1994) Recurrence of yaws outbreak in Thailand. Southeast. Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 25(1): 152–156.

- World Health Organization (1953) Proceedings of First International Symposium on Yaws Control. WHO Monograph Series, no. 15. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (1982) Treponematoses Research: Report of a WHO Scientific Groups, Technical Report Series 6. WHO Monograph Series, no. 15. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (1986) Endemic treponematoses. Weekly Epidemiologial Record 61: 1.

- World Health Organization (1995) Informal Consultation on Endemic Treponematoses. WHO Monograph Series, no. 15. Geneva, Switzerland 6–7 July 1995 (WHO/EMC/95.3). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.