This sample Juvenile Violence Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

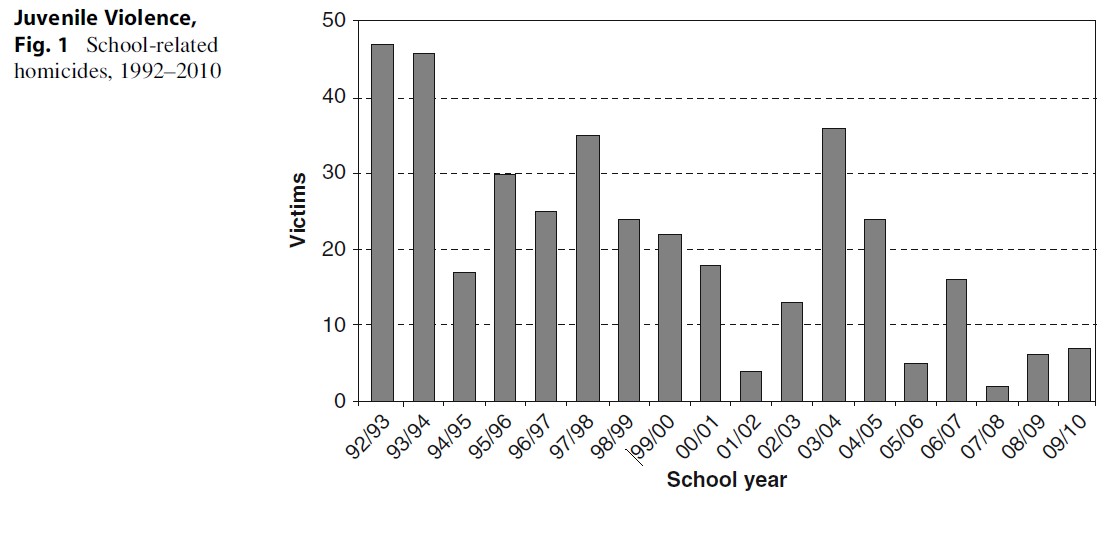

In the mid-to late 1990s, America was seemingly faced with a frightening epidemic: senseless acts of large-scale violence taking place in ostensibly safe, middle-class schools. Multiple instances of rampage-style shootings occurred in suburban and rural locales across the nation, the most deadly of which was the April 20, 1999 massacre at Columbine High School. Schools no longer felt safe. However, despite several isolated cases of school shootings involving multiple (oftentimes random) victims, schools were safe. In fact, by the late 1990s, school-related homicides were on the decline – a trend that has continued to the present. Thus, notwithstanding the seriousness of the rampage school shootings of the late 1990s, defining the problem as an epidemic was a hyperbolic overreach. Figure 1 displays school-related homicides since the early 1990s. As shown, the actual count of homicide victims has remained relatively low over time.

Despite this disjuncture between impression and reality with respect to school danger, juvenile violence – both inside and outside of school – remains a pressing concern for the public, criminologists, and criminal justice professionals alike. As such, it is important to have timely and accurate data on which to base policy. Without such data, criminal justice policies are more likely to be based on media-driven panics, as in the last 10–15 years, when ineffective and unnecessary measures, including zero-tolerance and fortress-like access control, were implemented within schools.

The purpose of this research paper is to review patterns and trends in juvenile violence, using the most up-to-date data available. The first section of the paper provides definitions and describes the categories of violence used by law enforcement officials and researchers. The second section provides some historical context for the state of juvenile violence in the United States today. This is followed by a review of trends in juvenile violence, examining how different types of offending have shifted or remained stable over the years. This section also briefly highlights several explanations for juvenile violence. The paper concludes with a discussion of policy implications emerging from the juvenile violence data.

Definitions Of Juvenile Violence

Juvenile violence is defined as the threat, attempt, or actual use of force by one or more persons that results in physical or nonphysical harm to one or more persons, committed by a person under the age of 18 (Barkan 2009). Generally, behavior is only considered “violence” if the perpetrator caused harm (either physical or emotional) to a victim. Juvenile violence can be classified in a number of different ways, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s designation of Part I (criminal homicide, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) and Part II (less serious acts such as carrying a weapon and simple assault) violent crimes.

A Brief History

A comprehensive history of juvenile violence is beyond the scope of this research paper. However, because the majority of the information presented here refers to the modern period (i.e., mid-1970s to the present), it is important to provide some context. Juvenile violence is hardly a new phenomenon. While data and research on such behavior have increased in sophistication over time, juveniles have presumably engaged in illegal acts of violence throughout history. Records indicate that the first juvenile to be sentenced to death in Colonial America was Thomas Graunger, for the offense of bestiality committed in 1642 (Twersky-Glasner 2007). Reasonably valid statistics are not available until the nineteenth century. Before that time, juveniles accused of crimes were often treated as, and imprisoned with, adults by the criminal justice system. William Blackstone’s Commentary on the Laws of England, from which American Law in the eighteenth Century was largely derived, argued that the “malice supplies the age” – that is, the seriousness of the offense determined how the offender was treated (ABA 2007). With the establishment of houses of refuge in 1820, juvenile offenders began to be increasingly separated from adult offenders. Records of offenders incarcerated in reformatories from 1890 show that juveniles were imprisoned for such crimes as homicide, rape, and assault, though these cases were rare (Walker 2007).

In 1899, the juvenile justice system with which most people are familiar today was ushered in with the formation of the first juvenile court in Cook County, Illinois. The model was initiated to provide guidance for wayward youth, rather than punishment. However, the middle part of the twentieth century saw many changes to juvenile justice, leading to a system that is increasingly similar to the adult system. While there remains a separation between juvenile and adult criminal justice systems, the distinction is blurring, with increasing stipulations allowing juveniles to be tried as adults (Singer 1996).

Juvenile Violence: Correlates, Trends, And Theory

There are two main sources of data that researchers use to study juvenile violence. First, is the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) which is released yearly by the FBI. The UCR is based on information gathered by local police departments who submit their data to the FBI. Thus, the UCR is comprised of “crimes known to the police.” The FBI also assembles and disseminates arrest data, which are more detailed – because of the inclusion of offender information – but underestimate the number of actual crimes that occur, and so may be somewhat biased (relatively few crimes, e.g., result in an arrest). UCR data for juveniles show that the number and rate of arrests for violent crimes is inversely related to the seriousness of the act – in other words, the likelihood of a juvenile committing and being arrested for a violent act declines as the seriousness of the crime increases.

In addition to the long-standing UCR program, the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) is a relatively recent development in which the police report a wide array of details on crimes, offenses, arrests, and victims, providing researchers with extensive information with which to examine the correlates and causes of crime. However, most police agencies (especially larger ones) do not as yet participate in the NIBRS initiative, thereby limiting its value for tracking patterns and trends in criminal behavior. Finally, the Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR), available in its current form since 1976, provides detailed information on over 90 % of the homicides in the United States. Because of the level of detail and high degree of coverage, SHR data are used here extensively for examining the nature and extent of juvenile violence.

With respect to “unofficial” sources of data on juvenile violence, the most common method used by researchers involves surveys. When conducting self-report surveys, researchers gather a sample of youth and ask them about whether they have committed various criminal acts. Examples of such studies are the National Longitudinal Study of Youth, the National Youth Study, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Research has indicated that despite some shortcomings, self-report surveys of violence tend to be fairly reliable and valid sources of information (Hindelang et al. 1981; Mosher et al. 2002).

One reason that academics and practitioners are concerned with juvenile delinquency is the disproportionate amount of crime committed by adolescents. Another reason for concern is the consistent finding that individuals who are involved in offending are also more likely to be victimized (Posick 2013). In other words, offenders are more likely to end up as victims compared to those who avoid criminal behavior. Taken together, juveniles are disproportionately involved in violence as both offenders and victims. Trends in juvenile delinquency allow researchers to highlight potential patterns and causes of crime and delinquency that can be addressed through prevention and intervention programs.

The Rise And Fall Of Juvenile Violence

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw a significant and disturbing surge in youth violence, including homicide. While the overall violent crime rate also rose as a whole during this period, this was largely due to increases in violence among juveniles and young adults. Criminologists disagree about exactly why the youth crime rate rose so rapidly during this period. Some have pointed to the emerging crack markets and the violence that surrounded drug selling in the 1980s, while others implicated the decline of intact families and family values. Regardless of the explanation of this increase, the rise in juvenile violence was experienced nearly ubiquitously across the nation, although it was far more pronounced in urban areas.

Following the sharp rise in juvenile violence that peaked in the early 1990s, the USA experienced a major decline in youth violence that in large measure continues to this day. Some of this decline was expected as rates were already so high that they essentially had almost nowhere else to go but down. However, research has indicated that this decline was steeper than expected and not only due to a return to normal levels. For example, by some measures, crime fell so much during the mid-and late 1990s that it reached levels not seen since the 1960s. Just as criminologists were interested in explaining the rise in crime rates from the 1980s until the early 1990s, they were equally interested in explaining the decline. Criminologists also disagree about why there was a drop in violent crime in particular, especially among juveniles. Researchers have attributed the drop to several factors, including:

- Shifting demographics (e.g., aging of the population)

- The decline of crack markets

- Effective policing strategies

- Legalization of abortion (reducing the supply of youths likely to commit crimes)

- Enhanced enforcement of gun laws

- Increased use of incarceration and longer sentences

Incarceration may or may not have been a major contributor to declining, rates of juvenile crime rates in the 1990s; however, with the “get tough” approach that began to characterize justice systems during that time period, juveniles were increasingly charged and punished as adults. Thus, incarceration of juveniles may have played a role in the juvenile crime drop. Despite the disagreement on the cause of the crime decline, there is little debate over the extent of this decline.

More recent trends in juvenile violence show that while rates declined from the early 1990s to the early twenty-first century, they now appear to be plateauing. Research suggests, however, that some forms of juvenile violence, such as gang activity, are rebounding. Predicting where the trend will move over the next decade is rather difficult; only time will tell.

Trends within the United States show peaks and valleys, but the rank order of the country in comparison to others around the globe has remained steady. There is little controversy over the violent nature of the United States in comparison to other developed countries. The USA remains consistently ranked near the top in violent crime, particularly murder. Per capita, the USA is one of the most lethal developed nations in the world. These rates are largely driven by violence by teens and young adults. Self-report surveys also confirm this pattern. The International Self-Report of Delinquency-II (ISRD-II) study has shown that youth in the “Anglo-Saxon” country cluster (which is comprised of Ireland, Canada, and the United States) has the highest rates of violence (Junger-Tas et al. 2012).

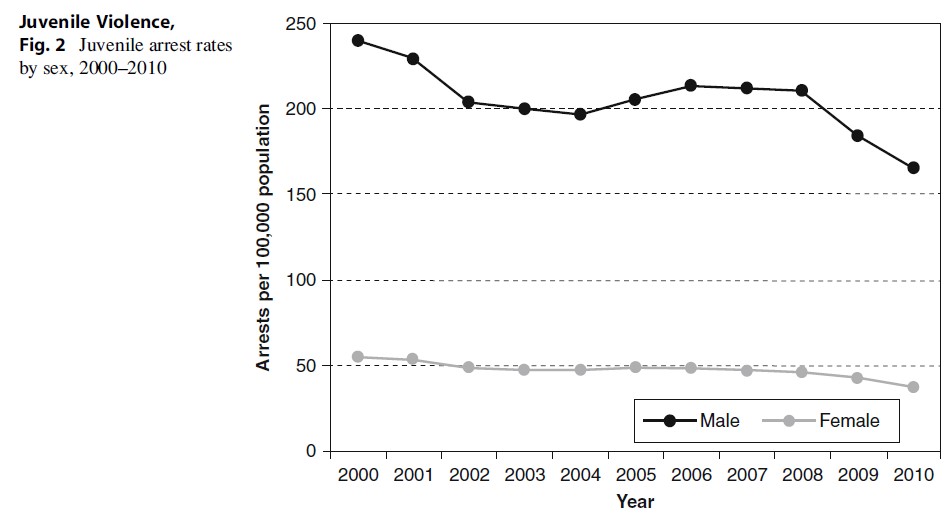

Juvenile crime rates have risen and fallen but there are certain elements of juvenile offending that have remained fairly consistent across time. For example, males are more likely than females to be involved with violent crime, and this holds across all ages and demographic groups. This fact is illustrated in Fig. 2.

As can be seen in Fig. 2, which displays UCR arrest data from 2000 to 2010 for males and females under the age of 18, males have a consistently higher arrest rate than females. The figure shows all Part I violent crimes combined (homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault). Interestingly, the trend for that time period was very similar for both males and females, dipping a bit around 2002, peaking around 2008 and then falling again in 2010. While males have higher arrest rates than females for all violent crimes, the disparity is most stark for homicide, robbery, and especially rape. The violent crime in which male and female rates are the closest is aggravated assault (where male rates are around three times higher than female rates).

Youth Homicide

Homicide, or lethal violence, is the most feared crime and also the one for which the most detailed information (provided by the Supplementary Homicide Reports) is available. Data indicate that lethal violence is not distributed evenly across the population. In other words, there are certain clear and consistent demographic, geographical, and temporal patterns that data have revealed with respect to juvenile homicide. The following figures explore how lethal violence is distributed demographically and geographically, and how these patterns have changed over time.

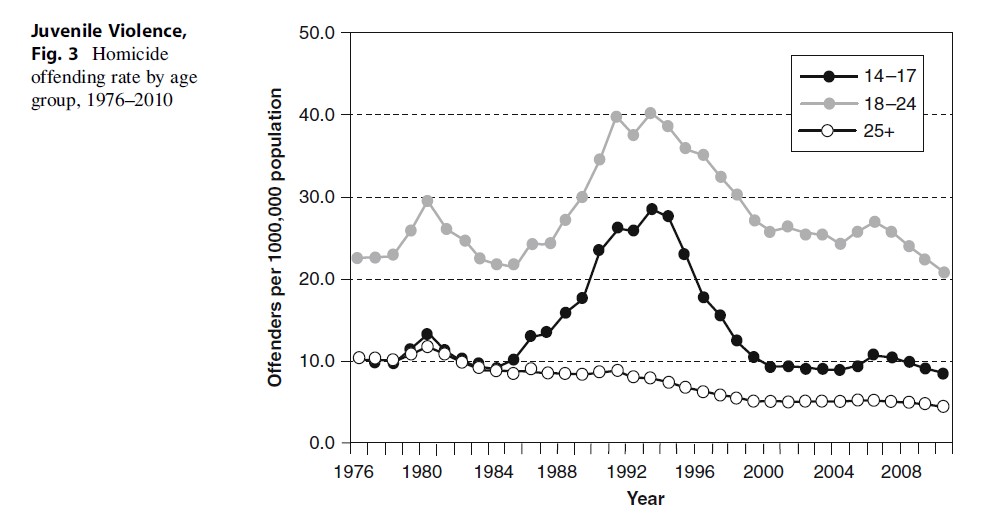

As is shown in Fig. 3, homicide is an offense committed disproportionately by juveniles and young adults. People over 25 years of age have a much lower rate of homicide. Young adults ages 18–24 are the most likely homicide perpetrators followed by youth ages 14–17. In terms of trends, homicide rates for all age groups increased in the 1970s and then began to decline in the early 1980s. Prior to the 1980s, the homicide rates for youths aged 14–17 and those aged 25 were virtually indistinguishable. However, as noted above, at that point, there was a noticeable spike in homicide by young offenders. By the early 1990s, the homicide rates for both the 14–17 and 18–24 age categories had nearly doubled their 1980 levels. Interestingly, the homicide rate for the over 25 age group remained relatively unchanged during the 1980s, compared to the other two age groups. During this time, some scholars worried about a violence epidemic gripping the nation’s youth and argued that the existence of “super-predators” may account for some of this increase in violence and indeed would continue to keep homicide rates high (Bennett et al. 1996).

However, as discussed earlier, in the United States as well as other western, industrial nations, beginning in the early 1990s, crime began to fall. Homicide rates dipped to the lowest they had been in decades. As is shown in Fig. 3, homicide rates for juveniles and young adults stabilized around the year 2000, but since then have continued to dip. This “great American crime decline” remains largely unexplained, although the reductions in the crack cocaine market and use of handguns by juveniles likely are contributing factors (Blumstein and Wallman 2006). As Fox et al. (2012) note, the rise of the crack market in inner cities during the late 1980s and early 1990s resulted in a dangerous and often very violent “arms race” in which profits had to be protected by the youths directly involved. It appears that when this market declined, the juvenile homicide rate followed suit.

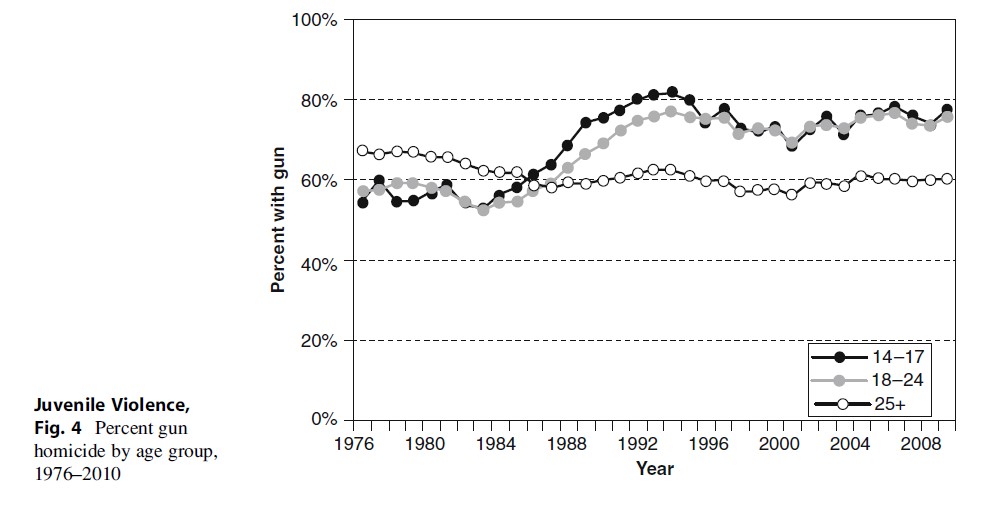

The emerging crack market required that drug couriers defend themselves and their territories with deadly weapons, namely, guns (Blumstein 1995). As shown in Fig. 4, homicides involving guns increased in the mid-1990s and then declined for both juveniles and young adults. Much like the trend shown in Fig. 3, the rate of homicides using a gun did not follow the same pattern for those aged 25 and older. Thus, it would seem that much of the decline in violent crime for juveniles and young adults was due to the changing crack market and the use of guns accompanying it. While crack use was still fairly prevalent, the marketplace for the drug was not nearly as volatile, competitive, and/or violent.

As can be seen in Fig. 4, in the past four decades, a solid majority of all homicides were committed with a gun. This finding is consistent across all age groups; in fact, the 14–17 and 18–24 age groups are almost identical in their pattern throughout the past several decades. During the peak of the violent crime spike, over 80 % of the homicides committed by the youngest group were committed with guns. Many researchers suggest that it may be the widespread availability of guns that contributes to high homicide rates in the USA and that this may explain some of the peaks and valleys in the patterns of lethal violence.

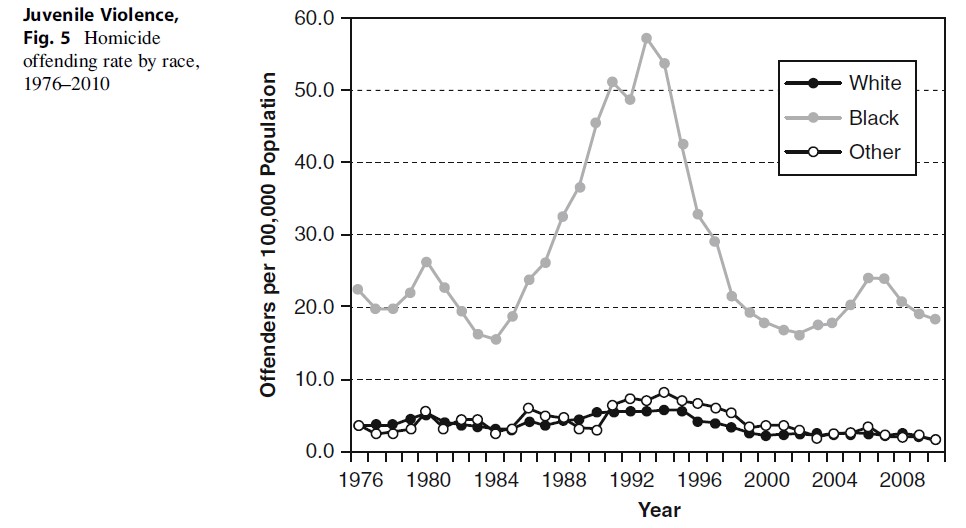

When one considers the saga of the crime decline in the 1990s following the “near-epidemic” levels in the late 1980s, perhaps the starkest trend can be found with respect to race. As shown in Fig. 5, the peak in homicides was much more drastic for blacks than for other racial groups. As is well known, the crack market was concentrated among minority groups, particularly blacks. This lends more credence to the thesis that the crack market was a large contributing factor to the rise and fall of juvenile violence since the mid-1980s.

In comparison to other crimes, homicide is unevenly distributed across racial groups. Regardless of the trend, blacks have a much higher homicide rate than any other racial group. Whites and other races have had almost identical rates throughout the last few decades, which range from about four times lower (in the early 1980s) to about six times lower (in the midto late 1980s) than the rate for blacks.

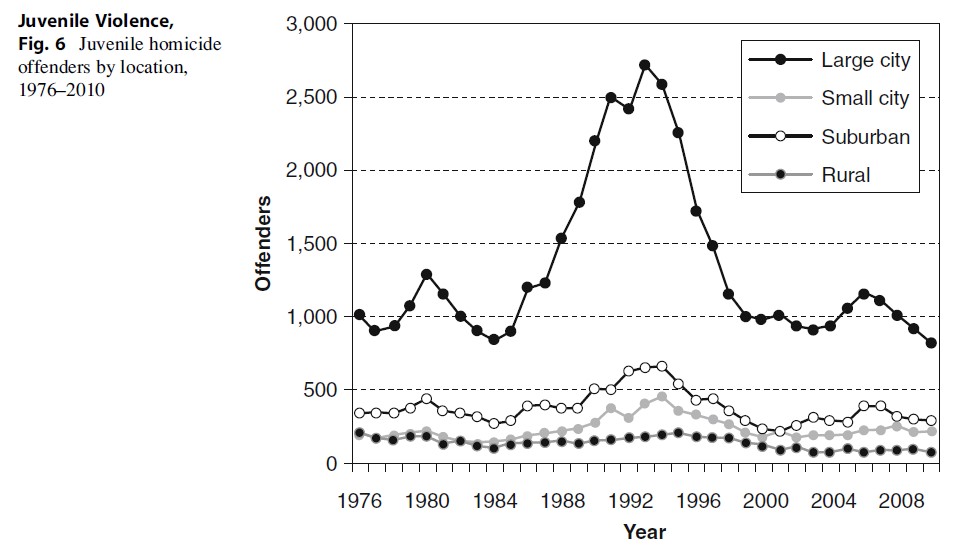

The crack market, as previously noted, was concentrated in the minority-dominated, inner cities. As shown in Fig. 6, the rise and fall of juvenile homicides was most pronounced in large cities. This again supports the thesis that the crack market and associated gang activity played a large role in juvenile homicide patterns since the early 1990s. Nonetheless, juvenile homicide rose and fell in cities of all sizes, suggesting that crack and gun use were not the only factors affecting violent crime rates.

In general, homicide is not evenly distributed geographically and this is true for juvenile homicide as well. As Fig. 6 indicates, the highest juvenile homicide rates are found in large cities. These are followed by suburban, small cities, and rural areas. The disparity between large and smaller cities with respect to juvenile homicide is similar to that between blacks and other races, as discussed previously. For example, at the point of the homicide peak, large cities had a homicide rate of more than four times that of other city sizes. That this disparity (despite some fluctuations) is relatively consistent across time suggests that factors such as poverty, relative deprivation and “subcultures of violence” may contribute to the variation in homicide rate by city size. A counterargument to the “more guns, more violence” hypothesis is that guns are also prevalent in rural areas where hunting and gun culture is prominent. Perhaps it is not guns alone, but guns in conjunction with a culture of violence that influences violent crime rates.

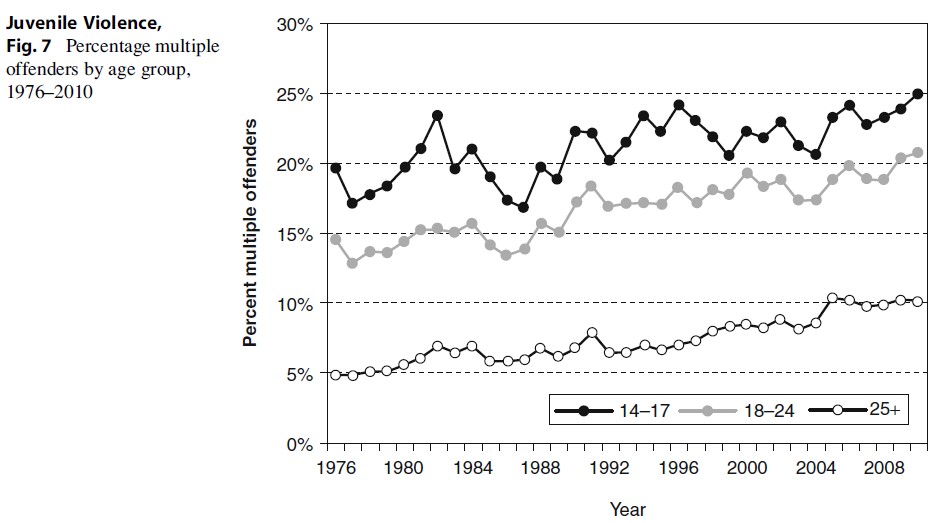

Figure 7 illustrates trends by age group for homicides committed by multiple offenders. There is a near-linear increase over time for each age group, suggesting that more homicides are being committed in partnerships. While homicide is generally committed by a lone offender, younger individuals are more likely than older individuals to commit homicide with other offenders. In other words, violent offending is more of a group activity among youths. Younger individuals are more likely to associate with and be influenced by delinquent peers, while older individuals are more likely to be involved with family or work. This is concordant with research that shows juveniles are more affected by peer influence and more likely to offend in groups early in life as compared to later (Farrington 2003). About 20–25 % of homicide offenders ages 14–17 commit the crime with the help of accomplices, compared to 15–20 % for 18–24-year-old assailants and only about 10–15 % for offenders over age 25. When older individuals do commit lethal violence, it is more likely to be done alone – perhaps related to domestic or intimate partner violence. In general, the literature suggests that adults tend to commit crime alone, although lethal violence in particular is among the least likely to be committed with co-offenders.

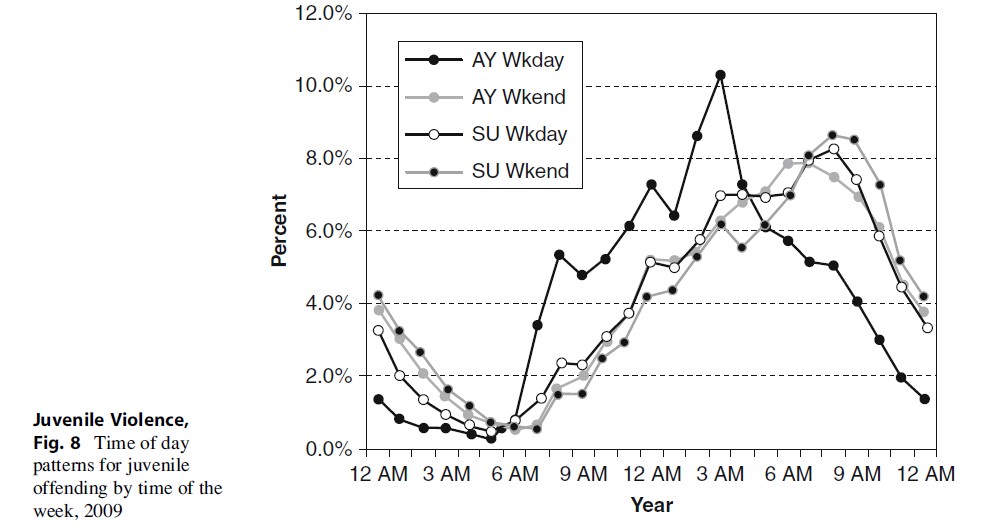

The timing of juvenile violence (e.g., time of day, day of week, and season of year) is another key piece of information with clear policy implications. Logic would suggest that youth crime should peak in the early afternoon, directly after school lets out), and data support this notion. In Fig. 8, NIBRS data are used to examine patterns of violent crime committed by juveniles by time of day for the academic year (AY) and summer months (SU), for weekdays and weekends separately. While the overall patterns for offending are fairly similar, there are two deviations that are worthy of attention. First, a spike is apparent in offending around 3 pm on weekdays during the school year. This uptick is related to the routine school-day activities of likely offenders and victims in the after-school hours. Students leave school around 2–3 pm, bringing together many youth who, now out of school but not yet at home, tend to be less supervised by teachers and parents. This situation is prime for both offending and victimization.

A second deviation from the general offending pattern is seen in offending around 9 pm in the summer and on the weekends. Again, this is likely due to the routine activity patterns by young people (those aged 18 and under) during these hours. After work and during the weekends, adolescents often enjoy partying and carousing. This brings together young people who may be under the influence of alcohol or drugs in environments with little formal supervision. During the academic year, when youth are in school, the percentage of total offending during these later hours is smaller because students are more likely to be involved with schoolwork or asleep during this time of day.

Figure 8 suggests that crime prevention efforts should be focused on peak hours of offending (which covary with victimization) to prevent violence. Some research in criminology has examined the extent to which after-school programs can reduce offending. This research has shown that the peak in offending after school tends to be starker for official records than for self-reports. In addition, after-school programs do, in fact, reduce juvenile offending, in part because of an increase in supervision, but more importantly because of effective socialization that reduces antisocial tendencies (Gottfredson et al. 2001, 2004).

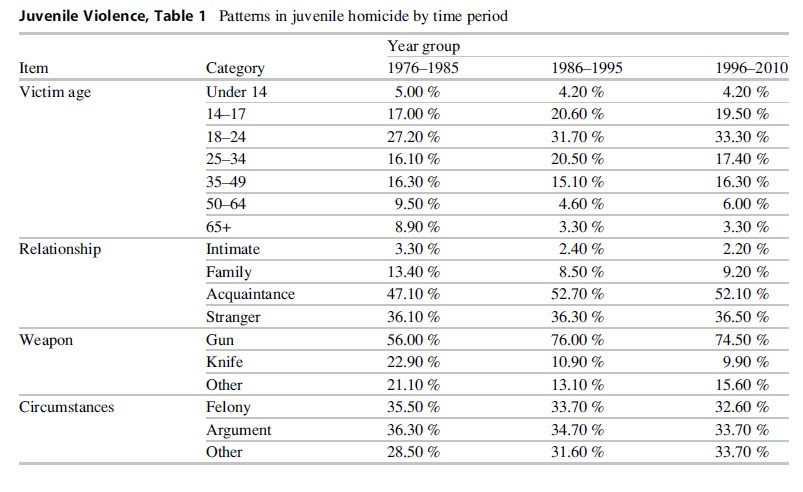

The discussion of trends and correlates of juvenile violence closes with a look at the characteristics of juvenile offenders, including their victims across several decades. These data are shown in Table 1. The first panel of Table 1 illustrates patterns with respect to victim age. Since the first time period (1976–1985), victims of teenagers have tended to be younger. For example, in the period between 1976 and 1985, 17 % of victims were aged 14–17 compared to around 20 % in later years. In addition, about 18 % of victims were over the age of 50 in the first time period, compared to around 8–9 % in later years. Overall, mirroring the offender ages for homicide, the largest age category for victims in all years is 18–24. This supports the argument that offenders and victims of lethal violence tend to share demographic characteristics.

In terms of the relationship between victim and offender for juvenile homicide, most are acquaintances. The relative rank ordering of these relationships has remained consistent over time. However, there has been an increase in the percentage of victims who are acquaintances, and a decrease in family homicides since the 1976–1985 time period. The percentage of homicide victims who are intimates or strangers has remained relatively consistent over time.

Juvenile homicides also predominantly involve guns. This is shown in the third panel of Table 1. Interestingly the percentage of juvenile homicides using a gun increased dramatically in the mid-1980s from 56 % to 76 %. This follows the trend shown in Fig. 4.

The circumstances leading to juvenile homicide have not changed much over time. As shown in the bottom panel of Table 1, the three classifications of circumstances (felony-related, argument-related, or other) are relatively evenly distributed, with argument-related episodes slightly more commonplace. Adolescents tend to act impulsively and have lower self-control. As a result, most juvenile homicides appear likely spontaneous or episodic, rather than being planned and premeditated.

Conclusion

Juvenile violence remains a significant concern for policy-makers, criminologists, and the public alike. Too often, however, misconceptions fueled by sensational media reports lead to policies or programs that either do not work or actually serve to make things worse. In the 1980s, two particular programs (Scared Straight and D.A.R.E.) were popular and supported handsomely by government funding. Unfortunately, evaluations of these initiatives have shown that they did not work; in fact, in some situations, they actually increased the risk of offending (see Mackenzie 2006).

Because juvenile crime – especially violence – remains a significant concern, reducing its occurrence continues to be a priority. The best interventions and prevention strategies are based upon a solid understanding of the patterns of juvenile violence, including prevalence, trends, and correlates. As discussed here, juvenile violence has followed some pronounced trends over the last 30 years, including a major spike in the 1980s (especially for inner-city, minority youths using handguns), followed by a large decline that in large measure continues to this day.

Juvenile violence also seems to cluster in terms of day of the week and time of day. As we have shown, crime tends to increase on the weekends and during after-school hours. This information represents a powerful tool for policy-makers who wish to design effective interventions that will decrease juvenile violence. However, it is important to bear in mind that it is not solely supervision or surveillance that seems to be what matters with respect to reducing violence, but impacting attitudes and other risk factors related to crime. Those wishing to reduce or prevent juvenile violence would do well to remember that it is not a simple phenomenon, but one that is complex and influenced by a variety of factors, including peer influences and lack of self-control (see Farrington 2007). Understanding what juvenile violence is (and is not) as well as its trends and correlates is an important first step in achieving this goal.

Bibliography:

- ABA (2007) Dialogue on youth justice. American Bar Association, Washington, DC

- Barkan SE (2009) Criminology: a sociological understanding. Pearson, Upper Saddle River

- Bennett WJ, DiIulio JJ, Walters JP (1996) Body count: moral poverty and how to win America’s war against crime and drugs. Simon and Schuster, New York

- Blumstein A (1995) Youth violence, guns, and the illicit drug industry. J Crim Law Criminol 86(1):10–36

- Blumstein A, Wallman J (2006) The crime drop in America. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Farrington DP (2003) Developmental and life-course criminology: key theoretical and empirical issues— the 2002 Sutherland award address. Criminology 41(2):221–256

- Farrington DP (2007) Developmental criminology and riskfocused prevention. In Maguire M, Morgan R & Reiner R (eds) The Oxford handbook of criminology (Vol. 4, pp. 657–701). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- Fox JA, Levin J, Quinet K (2012) The will to kill. Pearson, Upper Saddle River

- Gottfredson DC, Gottfredson GD, Weisman SA (2001) The timing of delinquent behavior and its implications for after‐school programs. Criminol Public Policy 1(1):61–86

- Gottfredson DC, Gerstenblith SA, Soule´ DA, Womer SC, Lu S (2004) Do after school programs reduce delinquency? Prev Sci 5(4):253–266

- Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG (1981) Measuring delinquency. Sage, Beverly Hills

- Junger-Tas J, Marshall IH, Enzmann D, Killias M, Steketee M, Gruszczynska B (2012) The many faces of youth crime: contrasting theoretical perspectives on juvenile delinquency across countries and cultures. Springer, New York

- Mackenzie DL (2006) What works in corrections: Reducing the criminal activities of offenders and delinquents. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Mosher CJ, Hart TC, Miethe TD (2002) The mismeasure of crime. Sage, Beverly Hills

- Posick C (2013) The overlap between offending and victimization among adolescents Results from the second international self-report delinquency study. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. doi: 10.1177/ 1043986212471250

- Singer SI (1996) Recriminalizing delinquency: violent juvenile crime and juvenile justice reform. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Twersky-Glasner A (2007) Juvenile violence, 1600–1800 (Colonial Era). In: Finley LL (ed) The encyclopedia of juvenile violence. Greenwood Press, Westport

- Walker L (2007) Juvenile violence, 1861–1885 (Civil War Era). In: Finley LL (ed) Encyclopedia of juvenile violence. Greenwood Press, Westport

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.