This sample Co-Opetition Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Co-opetition refers to simultaneous cooperation and competition between different individual or organizational actors. In this research-paper, we focus on companies or firms and their co-opetition strategy, that is, the ways in which firms simultaneously compete and cooperate in order to create and pursue current and future advantages for themselves. Traditionally, firms either collaborated or competed with each other rather than doing both at the same time with the same firms. The emergence of co-opetition has changed that and brought intriguing promises as well as challenges to firms. Business examples of co-opetition abound. As early as 1976, major Japanese semiconductor and electronic firms—Fujitsu, Hitachi, Mitsubishi Electric, NEC, and Toshiba—collaborated in the Very Large-Scale Integrated (VLSI) Technology Research Project. Recent business press (Coy, 2006) suggests that “sleeping with the enemy” or learning to work with rivals is becoming very important. The importance of co-opetition seems to be even greater in technology intensive industries, partly because of intensifying technological battles and complexity of technologies. As SAP CEO Henning Kagermann stated, “[T]he power of co-opetition will only grow as products become more complex and as competition widens globally” (as cited in Coy, 2006). Other recent examples of co-opetition are Microsoft and SAP developing Duet software, LG and Philips developing panels for large TVs, and MedUnite being founded by seven competing U.S. health care insurers to develop an efficient Internet-based connectivity system to reduce health care costs. The increased popularity of co-opetition is indicated by the fact that over 50% of collaborative relations (strategic alliances) are between firms within the same industry, that is, among competitors (Harbison & Pekar, 1998).

In discussing the increasingly popular concept of co-opetition, we begin with a detailed illustration of collaboration between two fierce rivals—Samsung Electronics and Sony. This case study, focused on a high-technology context, helps to illustrate why firms engage in co-opetition as well as the kinds of dynamics and challenges firms face when they collaborate and compete at the same time. Next, we briefly discuss the intellectual roots of the co-opetition construct. We then introduce a framework that will help to develop a broad understanding of co-opetition. Next, we provide a summary of the literature and an exploration of the drivers, processes, and outcomes of co-opetition. We conclude the research-paper with an illustration of future research directions that can strengthen and enrich the co-opetition construct.

S-LCD And Co-Opetition Between Samsung And Sony

For many years, Samsung and Sony have been fierce rivals in the electronics market, with Samsung Electronics’ key mission being to unseat Sony in TV sets. The roots of their rivalry stretch back to Japan’s colonization of Korea in the early 1900s. Yet, in 2003, the two firms formed a joint venture (JV) called S-LCD to develop and produce seventh generation (46 inches or smaller) LCD panels for flat screen TVs. To underscore Sony’s commitment to the JV, Sony threw a party in Japan for a select group of Sony and Samsung engineers. Some public reaction in Japan to the deal was visceral (Dvorak & Ramstad, 2006): Anti-Korean slurs and accusations that Sony was a traitor appeared on chat boards in Japan. Government officials had urged Sony to ally with a Japanese company. In January 2004, Sony said it had pulled out of a secretive, government-backed, LCD-panel development group in order to address concerns that the confidential technology would fall into Samsung’s hands.

In the last 3 years, these two companies have not only deepened their resource commitments to the JV, but have also had tremendous success as the LCD technology developed by the JV helped both companies to gain market share in large screen TVs and push the LCD technology in the market (Ihlwan, 2006). They have more than doubled their investments and recently signed a contract for eighth generation technology (LCD panels of more than 46 inches). The potential for future success is clear from the following statement by Mr. Wonkie Chang, CEO of S-LCD:

Our success in 7G production has already provided a springboard for a new round of growth at S-LCD. Once our 8G line is up and running, we will assume the leading position as a LCD TV panel manufacturer for the 50-inch LCD TV range.

Each party owns 50% of the venture, with the CEO from Samsung and the CFO from Sony. Samsung brings its technological strengths in the LCD technology, which it has used primarily in small-screen electronics such as cell phones and computers. Sony brings its strengths in television and consumer electronics, particularly its market leadership in television. Overall, this oddest of alliances between two cutthroat competitors so far seems to be working out for both sides. The JV was very attractive for both Samsung and Sony for several reasons. Samsung needed help from established players like Sony on the TV market in order to learn about the market forces. Samsung was a second-tier manufacturer of electronics until the late 1990s. It poured huge sums into making memory chips and LCD panels—out-investing the Japanese companies that had dominated those businesses. While Samsung was able to make panels with relatively static images for products like computers, it faced challenges in making them look as good with moving pictures for TVs. So Samsung executives thought that a JV with Sony would let Samsung learn from and use Sony’s TV-making expertise to LCD panels. Samsung could use the same wide viewing-angle technology that many of Sony’s Bravia sets had. Second, Sony’s difficult demands for the technology and product quality helped push Samsung’s panel technology ahead of others. This was especially important given Panasonic’s dominance in the rival PDP technology. Finally, competition with Sony was likely to help Samsung hone its own TV designs.

On the other hand, while flat panel TV sets were spreading rapidly in the market, Sony had neglected to invest in them. With TVs accounting for around 20% of Sony’s electronics revenue, executives realized that the company had to get into flat panels fast. Samsung had developed a huge lead in technologies like LCDs that Sony lagged behind. Moreover, without the S-LCD, Sony’s TV business would have been in great trouble as Sony had announced that its TV division would post a $1 billion loss in the fiscal year ending in March 2006 (Dvorak & Ramstad, 2006). When LCD panels were available from S-LCD, Sony was able to use the panels in its new LCD TV line called Bravia, which was an instant hit and Sony unseated Sharp Corporation from its top market position in LCD TV sales in the United States. Thus, while Sony was experiencing deeper level problems in the large, flat screen TV market, the S-LCD provided the much needed help to Sony.

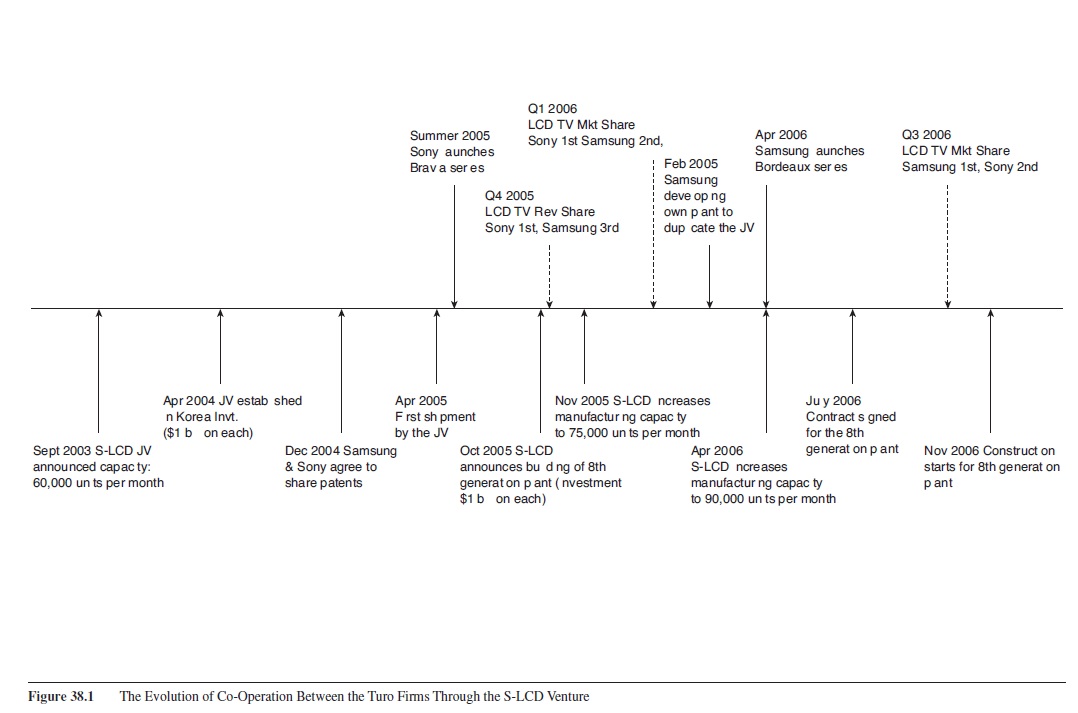

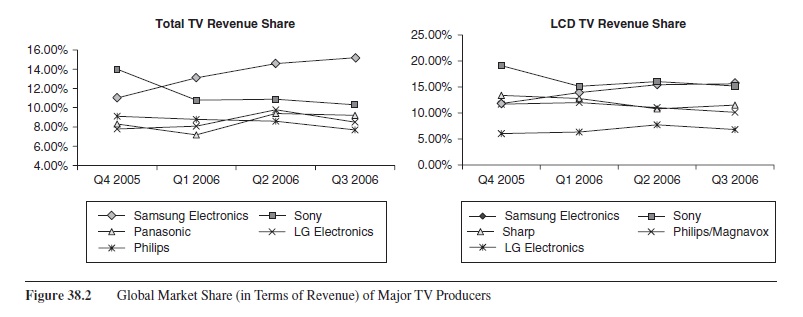

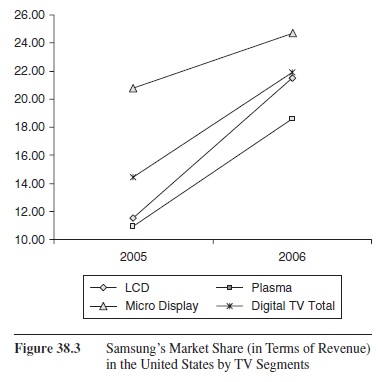

Figure 38.1 summarizes the evolution of co-opetition between the two firms through the S-LCD venture. In Figure 38.1, cooperative activities are listed at the bottom and illustrative competitive activities and their outcomes are listed on the top. Figure 38.2 illustrates change in market share of major TV producers including Samsung and Sony. Figure 38.3 illustrates Samsung’s substantial improvement in its market position in the TV industry, particularly in the LCD segment of the industry where co-opetition is occurring through the S-LCD.

Figure 38.1 summarizes the evolution of co-opetition between the two firms through the S-LCD venture. In Figure 38.1, cooperative activities are listed at the bottom and illustrative competitive activities and their outcomes are listed on the top. Figure 38.2 illustrates change in market share of major TV producers including Samsung and Sony. Figure 38.3 illustrates Samsung’s substantial improvement in its market position in the TV industry, particularly in the LCD segment of the industry where co-opetition is occurring through the S-LCD.

The birth of S-LCD changed the dynamics among LCD TV makers including the parents of the S-LCD venture. Sharp’s leadership with its Aquos models was challenged by Sony’s Bravia because of its high picture quality. By the end of 2005, Sony’s LCD TVs took the world’s number one spot. Samsung countered with its new Bordeaux model that helped it gain significant market share. The success of the JV led to the building of a $3 billion eighth generation plant, which will produce LCD panels that will directly compete with plasma sets in the 50-inch class market. Analysts say a widening investment gap between S-LCD and the rest of the industry pack will likely give the SonySamsung venture a clear lead in LCD TV screens. Sony believes that, given the cost savings, it can keep developing popular LCD TV models such as the Bravia and improve its competitive standing in the industry.

Figure 38.2 Global Market Share (in Terms of Revenue) of Major TV Producers

Figure 38.2 Global Market Share (in Terms of Revenue) of Major TV Producers

At the same time, this co-opetitive relationship has certainly brought multiple management challenges that are illustrative of co-opetition dynamics. For example, in order to prepare itself to work with a Japanese partner, key Samsung engineers traveled to Sony’s TV headquarters in Tokyo, learning what features Sony TV engineers focused on. Samsung engineers were able to learn finer details such as a new light Sony had developed to go behind the LCD panel, which would let the TV display a wider range of colors. Because Sony jealously guards know-how about its TVs, Samsung was able to see so much only because it was a partner. Sony engineers conceded that Samsung could eventually use Sony’s technology to compete against them. But given the nature of the consumer electronics industry, they thought it was hard to keep secrets long anyway, and being open with Samsung was key to making the JV work. Sony engineers said, “If we put up barriers, they’ll close up too.” Yet, Sony engineers also worry that Samsung will eventually use Sony’s TV expertise to beat the Japanese company. Executives at both companies clearly had concerns about working so closely with a direct rival. For example, Sony pressed Samsung’s team for panels that could show a greater array of colors, from a wider viewing angle, at a higher resolution than the industry standard. Samsung was asked to speed up its development schedule by as much as a year. Initially, Samsung’s research and development (R&D) team was unwilling, but it eventually agreed to speed up the timetable (Dvorak & Ramstad, 2006).

Figure 38.3 Samsung’s Market Share (in Terms of Revenue) in the United States by TV Segments

Figure 38.3 Samsung’s Market Share (in Terms of Revenue) in the United States by TV Segments

An additional complication was that Sony and Samsung also represent countries that have traditionally considered keeping the lead in technological innovation a matter of national pride. Although both companies say that nationalistic concerns play no part in their choices of who to partner with, the alliance certainly shocked the public in both countries. As noted earlier, it prompted complaints on Sony-related message boards and forced Sony to drop out of a key Japanese industry technology alliance.

In summary, the S-LCD case clearly illustrates that firms, especially those engaged in leading-edge technologies and products, often find it critical to collaborate with fierce rivals in order to push the technology frontier and to create mutual advantage. In order to understand the dynamics of co-opetition in a more sophisticated manner, we will now take a brief look at the historical underpinnings behind the co-opetition construct.

History And Intellectual Roots Of Co-Opetition

The term co-opetition was popularized by the bestselling book titled Co-Opetition by Brandenburger and Nalebuff that was published in 1996. Although the label itself was coined by Noorda, then CEO of the technology company Novell, Brandenburger and Nalebuff’s book presented it in a compelling and usable manner to a broad business audience. Of course, the idea of simultaneous cooperation and competition has been around for much longer. For example, the maxim “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” has long been a staple of political and military strategy. This section provides a brief overview of the evolution of the co-opetition construct: We begin by summarizing the main elements of co-opetition as articulated by Brandenburger and Nalebuff, then we discuss the key intellectual strains that combined to help sustain the framework, and we conclude by sketching some of the practical developments that provided a welcoming environment for co-opetition and related ideas.

Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) began with the observation that the traditional view of business emphasized competition (“business is war”) and neglected the role of cooperation; thus, to them, co-opetition was a revolutionary mind-set that combines cooperation and competition. A central idea in co-opetition is that of complements such as hardware and software referring to products or services that increase the value of other products or services—as in your iPod becoming more valuable to you when you have more music available for it. Relating the idea of complements to Porter’s five forces model for industry analysis, Brandenburger and Nalebuff proposed the value net as a tool for mapping the set of competitive and cooperative relationships that a company is embedded in. In effect, the value net adds a sixth force, complements, to conventional analysis. (Brandenburger and Nalebuff stressed product complements, but resource complementarity is also crucial—in the S-LCD case study, e.g., it is evident that Sony and Samsung found productive complementarity between Sony’s TV-market expertise and Samsung’s technology resources.) To facilitate the systematic application of the co-opetition construct, Brandenburger and Nalebuff proposed a framework they call the PARTS framework, a mnemonic for players, added value, rules, tactics, and scope. The PARTS framework allowed for the systematic and careful analysis of the identities and incentives of current and potential players, the value contributed by each (including yourself), how the game is structured and played, the perceptions and mental models of the players, and the boundaries of the game as well as how games are linked to one another. Viewing business situations through the lens of the PARTS framework allowed strategists potentially to reconceive how the business game could be played, leading to the discovery of new ways to add value. Especially in high-technology industries such as information technology, Brandenburger and Nalebuff’s ideas found great resonance.

As practicing game theorists, Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) attributed much of the intellectual lineage of the co-opetition construct to game theory. In economics, game theory, of course, is a dominant intellectual framework for the disciplined analysis of rivalry and competition—and thus, a staple of undergraduate strategy classes. Classical game theory analyzes how players choose their strategies given the form of the game; for example, the concept of equilibrium arose from games of pure competition where the focus was often on zero-sum, single-stage games. However, as game theory evolved, greater attention was devoted to rivalry in repeated games, which highlighted the notion of cooperating and competing at the same time. When players know that they will have to deal with one another in the future, it changes the strategic logic of games—they must then consider not only the immediate consequences of their choices, but also how those choices will affect the long-term relationship. For example, the longer term benefits stemming from a continued good relationship can outweigh the immediate benefits of taking advantage of a rival. In this regard, Axelrod’s 1984 book The Evolution of Cooperation was of seminal importance, examining how cooperation can emerge in a world of self-seeking entities even in the absence of a central authority to coordinate their actions. Axelrod’s central statement of his thesis is

What makes it possible for cooperation to emerge is the fact that players might meet again. This possibility means that the choices made today not only determine the outcome of this move, but can also influence the later choices of the players. The future can therefore cast a shadow back upon the present and thereby affect the current strategic situation. (p. 12)

The concern with strategic action as embedded in ongoing relationships—Axelrod’s shadow of the future—was also reflected in the work of scholars other than game theorists. For example, the sociologist Leifer in his 1991 book Actors as Observers developed a sociological parallel to the economic logic of repeated games, drawing from an empirical analysis of chess games evidence of skilled players demonstrating skill in relationships with their rivals and a sensitivity to the balance between keeping the game going and exploiting opportunities to gain the upper hand.

Along with these core developments in game theory, several other notable academic works contributed to the popularity of co-opetition. Groundbreaking work in network economics by David, Katz, and Shapiro, among others, led the elaboration of crucial new insights into the nature of industries characterized by network externalities, complements, and positive returns. Observers such as Reich and Hamel in strategy documented instances of cooperative relations between rivals, highlighting their intricate nature as well as raising questions about the eventual consequences. Jorde and Teece (1989) called for the need to strike the right balance between competition and cooperation in public policy thinking (e.g., antitrust) as well as in business and corporate strategy. These and related intellectual developments during the 1980s and 1990s combined with the game theoretic focus on repeated games to provide the conceptual infrastructure for the co-opetition construct to emerge by the late 1990s.

As the co-opetition construct gained traction and evolved in intellectual terms, the term has been used to label a new philosophy, strategy, or approach that goes beyond the conventional contrasting rules of cooperation and competition (Luo, 2004a). In particular, from a philosophical perspective, the notion of co-opetition has been applied to formulate an “interdependent opposites” view of the fundamental relationship between cooperation and competition (Chen, 2006). As noted earlier, this research-paper adopts a strategy-focused view, which enables us to distinguish from the philosophical view that in any specific relationship both the cooperative and the competitive elements can be found (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000).

Of course, the intellectual roots did not exist in isolation from what was going on in the practical world of business. In fact, arguably, changes in the business world impelled some of the previously mentioned intellectual developments. For a long period, the idea of simultaneous cooperation and competition fell outside the pale of what was considered acceptable—for example, cartels such as OPEC were what often came to mind in such a context, suggesting that rivals were getting together to fix prices or to divide markets, that is, to transfer welfare from the consumer to themselves rather than to create value. However, this jaundiced view began to change as international competition intensified in the 1970s and 1980s, with managers and policymakers paying increasing attention to the competitiveness of their national champion industries and companies. Over time, there was a relaxation of antitrust strictures as the locus of competition shifted to cross-border, with the idea that domestic firms may need help in order for them to be competitive globally gaining currency. Japan was an early mover in this arena, as illustrated by the 1971 formation of the computer industry consortium in order to fight IBM. Equally well known is the Japanese VLSI Research Association mentioned earlier. In contrast, the U.S. policymaking establishment, steeped in the traditional mind-set that competition was the exclusive means to efficient resource allocation, took longer to admit that cooperation and competition could coexist. It was in 1984 that the National Cooperative Research Act (NCRA) was passed, embodying the idea that industry rivals, even while competing vigorously in product markets, could potentially benefit from pooling resources and sharing risks in precompetitive phases such as R&D. The NCRA set in motion a period of change during which antitrust policies evolved to accommodate cooperative activities between rivals, including research consortia (e.g., in the semiconductor industry) and JVs as well as other forms of strategic alliance—of which there was an explosion during the 1990s onward.

One interesting feature of the co-opetition construct’s trajectory has been its extraordinary appeal to the high-technology industry, with strategists such as Intel’s Grove acting as boosters. While the central ideas of co-opetition are certainly applicable to many industries including the most traditional ones, high-technology industries exhibit several characteristics that may accentuate the appeal of co-opetition. Such characteristics include many features of network economics—the presence of network externalities, the importance of complements, as well as patterns of geographic aggregation (e.g., the concentration of firms in Silicon Valley) that facilitate intense personal interaction between rivals. It could also be that the shadow of the future may fall more or less lightly in different industries: In fast-paced industries with uncertain technology futures, the incentive to cooperate may be greater than in other contexts. Whatever the reasons, the co-opetition construct appears to have enjoyed particular attention among high-technology strategists.

This section has outlined the key intellectual and historic developments that led to the emergence and popularity of the co-opetition construct. While we have not attempted to provide an exhaustive account of all the precedents to the notion, we hope that we have met the goal of situating co-opetition in its proper context in the reader’s mind. We now go on to elaborate on co-opetition in a finer grained manner through an organizing framework.

Co-Opetition: An Organizing Framework

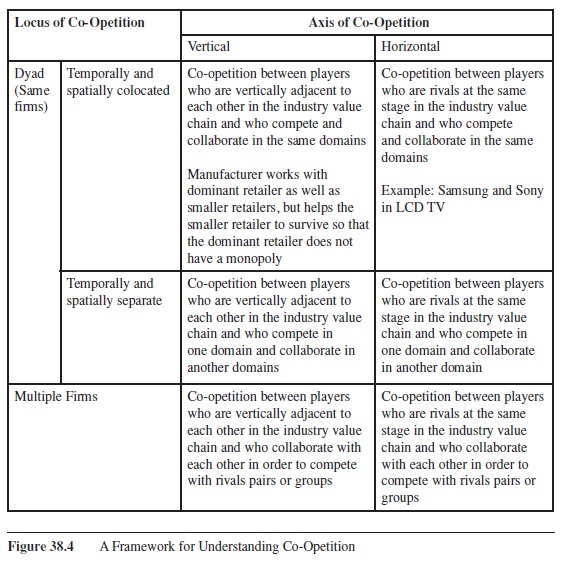

Although the basic meaning of co-opetition is straightforward, the concept has been loosely applied in various contexts, sometimes without clear specifications. To facilitate business and academic conversations about co-opetition, it is thus helpful to have a systematic scheme for grouping various types of co-opetition strategy. With this goal in mind, we classify co-opetition strategy according to (a) axis of business relationship, (b) number of actors involved, (c) level of analysis, and (d) locus of cooperation and competition. Figure 38.4 presents the organizing framework for thinking about the various types of co-opetition. To illustrate, the co-opetition between Samsung and Sony described earlier is an example of a horizontal bilateral relationship that is temporally and spatially colocated. We briefly describe the elements of the framework in this section.

Axis of Business Relationship

In the business press, co-opetition is mainly used to refer to collaboration with competitors. However, since Porter made popular the notion that competitive forces include industry participants of various kinds such as suppliers, buyers, potential entrants, substitutes, and incumbents, it is widely accepted that collaboration can take place between any pair of parties who may generate and appropriate value from the same pool (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996). Therefore, a co-opetition strategy can be defined as either vertical or horizontal, based on whether the players are vertically adjacent to each other in the industry value chain or are rivals at the same stage in the industry value chain.

The distinction just mentioned suggests that collaboration between industry rivals is horizontal co-opetition, as the actor firms involved belong to the same stage of the industry value chain. With regard to horizontal co-opetition, an interesting question arises as to whether co-opetition between industry rivals constitutes collusion. While the definition of collusion is often a contentious legal matter, we propose that collusion and horizontal co-opetition differ in a fundamental way. Specifically, the “cooperation” element in collusion is aimed at appropriating value illegally from other stakeholders (mainly customers, as in the case of cartels), whereas the cooperation element in horizontal co-opetition emphasizes creating value for all stakeholders by pooling competitors’ complementary resources. For instance, joint effort by rival firms to share R&D risks or to streamline their distribution systems and increase efficiency is closer to horizontal co-opetition than to collusion. In such a context, the benefits from improved efficiency can be passed on to customers or to the society as a whole.

Figure 38.4 A Framework for Understanding Co-Opetition

Figure 38.4 A Framework for Understanding Co-Opetition

Number of Actors Involved

A dyad is the basic unit for observing the employment of a co-opetition strategy. However, simultaneous cooperation and competition can exist among multiple players. For example, the whole population of rivals in the same industry may join forces in R&D consortia while still competing vigorously with each other in the product market. In fact, interesting dynamics can take place when greater numbers of players are involved in co-opetition. The complexity of co-opetition can be much higher for multilateral co-opetition than for bilateral co-opetition as an actor can strategize its relationship with one actor to gain competitive or cooperative advantages over other actors who also belong to the multilateral co-opetitive relationship. In other words, managing the relationships with different players can itself be a part of an actor’s co-opetitive strategy (Madhavan, Gnyawali, & He, 2004).

Level of Analysis

As previously noted, the number of players involved in co-opetition can be more than two. For simplicity, we focus on bilateral co-opetition and define the level of analysis for co-opetition according to the “organizational” level(s) of the two actors. In extant studies, co-opetition strategy has been investigated at the following levels: (a) interorganizational unit (which is intrafirm; Luo, 2005; Luo, Slotegraaf, & Pan, 2006; Tsai, 2002); (b) interfirm (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996; Carayannis & Alexander, 2004; Chien & Peng, 2005; Khanna, Gulati, & Nohria, 1998; Oliver, 2004); (c) firm government (Chaudhri & Samson, 2000; Luo, 2004b).

An interesting subset of the broad phenomenon of co-opetition is observed when the cooperative and competitive elements are separated at different levels of analysis. For instance, friendships and collaborative ties may exist between employees or managers from organizations that maintain formal competitive relationships in the market. In other words, cooperation can exist at the interorganizational-individual level while competition at the interorganizational-organizational level (Ingram & Roberts, 2000; Oliver, 2004). Viewed from a social network perspective, interfirm competition is embedded in the social network of organizational members. Such collaboration networks among individuals from competing organizations may help reduce the competitive tension at the interorganizational level (Ingram & Roberts, 2000) while simultaneously being constrained by institutional and organizational arrangements (e.g., antitrust regulations, confidentiality agreements between the firm and its employees, etc.; Oliver, 2004)

Locus Of Cooperation And Competition

Simultaneous cooperation and competition constitute severe complexities and cognitive-psychological challenges for business practice and academic research. For example, the human need for cognitive balance makes it likely that demands to compete and collaborate with the same other will place an individual at risk of cognitive dissonance. However, as suggested by Poole and Van de Ven (1989), such complexities can be resolved by temporal separation (which accounts for time) and/or spatial separation (which accounts for locality of activity). Thus, co-opetition strategies can also be classified into four basic forms using temporal and spatial separations (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Chen, 2006; Clarke-Hill, Li, & Davies, 2003; Poole & Van de Ven, 1989), with competition and cooperation taken place at the same “location” and in the same “time” as the most challenging form (see Figure 38.4). Also, the location of competitive and cooperative activities can be defined according to (a) product market, (b) geographic market, or (c) value chain stage or proximity to customers (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000).

To summarize, a co-opetitive relationship can be classified using the four dimensions of axis, number of players, level of analysis, and locus. Among the various types of co-opetition, bilateral co-opetition is the most basic unit for studying the phenomenon of co-opetition. (It is implicitly expected that knowledge derived from studying bilateral co-opetition can be extended to co-opetitive behaviors involving three or more players.) In some ways, bilateral, interfirm, horizontal co-opetition, which is the clearest ex-ample of “true” co-opetition, is arguably the most intriguing intellectually, as well as the most challenging managerially. Competing and collaborating with the same firm exposes the firm’s managers to cognitive-psychological stresses (e.g., managing cognitive dissonance), organizational complexities (e.g., developing separate information systems), and public policy traps (e.g., documenting that the collaboration does not entail anticompetitive motives and actions). The S-LCD case discussed earlier is one such example in which the challenges of co-opetition can be seen in their fullest development.

As noted earlier, co-opetition seems to be very common among firms in high-technology industries. We therefore briefly discuss next the factors that lead to the increased prevalence of co-opetition in such industries. This discussion, combined with the details presented on the S-LCD case, suggests that co-opetition will be even more popular in the future, and that firms in high-technology industries need to find ways to effectively pursue co-opetition strategies in order for them to survive and prosper.

Prevalence Of Co-Opetition In High-Technology Industries

The collaboration among Japanese firms for the VLSI project mentioned in the opening paragraph is an example of early co-opetition for technological development. Over 15 years ago, Jorde and Teece (1990) suggested that the changing dynamics of technologies and markets have led to the emergence of the simultaneous innovation model. For firms to pursue the simultaneous innovation model and succeed in innovation, they look for collaboration opportunities that allow them to bring multiple technologies and diverse and complementary assets together. With a focus on informal exchange of technology among competing firms, Von Hip-pel (1987) argued that collaboration for knowledge sharing among competitors occurs when technological progress may be faster with collective efforts rather than through individual efforts and when combined knowledge offers better advantages than solo knowledge. Thus, co-opetition is likely when technological standards are being developed and when combining multiple bodies of knowledge provides superior advantages. More recent research clearly shows the importance of co-opetition in technological innovation. Quintana-Garcia and Benavides-Velasco (2004) empirically showed that collaboration with direct competitors is important not only to acquire new technological knowledge and skills from the partner, but also to create and access other capabilities based on intensive exploitation of the existing ones. Their study found that collaboration with direct competitors contributes to technological diversity and adoption of a complementary approach to product development. Similarly, Carayannis and Alexander (1999) argued that co-opetition is particularly important in knowledge intensive, highly complex, and dynamic environments. Again, the S-LCD case certainly suggests that co-opetition is important in high-technology contexts.

It appears that a few key factors have contributed to the increased prevalence of co-opetition in high-technology industries: short product life cycle, technology convergence, and high R&D costs (Gnyawali & Park, 2007). We briefly explain them now.

Short Product Life Cycles

Because of the rapid pace of technological change, speed to market is becoming more essential to new product success (Lynn & Akgiin, 1998). Short product life cycles require companies to reduce time to market in order to launch their products at the right time to get reasonable profits during the useful lifetime of a product. Short product life cycles also require companies to fill the gap between their own exploration capabilities and those necessary to reduce R&D period. As a result, the likelihood of cooperation with competitors having excellent exploration capabilities increases. Oxley and Sampson (2004) suggested that profitability depends critically on firms’ abilities to create and commercialize new technologies quickly and efficiently. Experience in many industries suggests that some competitors have abilities to reduce time to market and that is the critical factor in cooperation with competitors.

Technological Convergence

While historically a particular product or device handled one or two tasks, through technological convergence, devices are now able to handle and interact with a wide array of media. For instance, virtually all entertainment technologies—from radio to television, to video, to books, and to games—can be viewed and played online. Another good example is mobile phones that are being designed not only to carry out phone calls and text messages but also to hold images, videos, and multimedia of all types. Even in traditional “metal-bending” industries such as automobiles, the electronics content is now a substantial portion of the value chain. Technological convergence has various effects. First, convergence may result in more complex and sophisticated technical developmental tasks. Due to high uncertainty in terms of both market and technology, companies tend to increase diversity; therefore, reducing failure rate is a key factor in alliances. In this sense, appropriate partners should have complementary resources for collaborative R&D alliances. Second, technological convergence offers companies opportunities to set industry standards. Besides competing to develop new technologies, companies (rivals) try to shape emerging industry structures and standards required to support their development and diffusion and that the creation of new industry structures and standards offers rivals an opportunity to build their technological attributes directly into society as institutional rules (Garud, 1994). Industry standards are also being set through competition between groups consisting of leading companies. These factors force companies to cooperate with competitors to get common benefits. Competitors (especially first movers) can cooperate with each other to win in a battle for industry standards with another competitor or a group of competitors (Gomes-Casseres, 1994). In the S-LCD JV case, for example, Sony and Samsung were able to contribute and integrate Sony’s technological expertise in television and consumer electronics and Samsung’s technological expertise in the LCD technology (used mainly in computers and small electronics) in developing the LCD technology for large size TVs.

High R&D Costs

The R&D spending of global companies is rapidly increasing, especially in the high-technology sectors. According to DTI’s the 2006 R&D Scoreboard published in United Kingdom, the top 1,250 R&D active companies in the world invested £249 billion (about $473 billion) in R&D in 2005-2006, which is up 7% from the previous year (a 5% increase in 2005). The following top five sectors account for 70% of R&D: technology hardware, pharmaceuticals, automotive, electronics, and software. Average R&D intensity (R&D as percent sales) is very high in these major sectors: pharmaceuticals and biotechnology (14.9%), software and computer services (10.4%), and technology hardware (8.2%). Over 50% of the R&D global 1,250 are in sectors with R&D intensity of 5% or more. Such massive R&D costs are a strong incentive for companies to cooperate with competitors with a large resource base. Creating a co-opetitive relationship is an effective way to combine R&D expenses and expertise (Zineldin, 2004). In practice, some alliances occur to combine complementary resources, where one side has a superior financial ability and the other has superior technologies. Sharing of costs and risks is especially important when technological uncertainty is very high. Given the existence of competing technologies (e.g., plasma vs. LCD) and uncertainty of the future of the LCD technology itself for TV, neither Samsung nor Sony was willing to go solo in developing the technology for large LCD panels. Pooling the resources of both partners helped share the developmental costs and technological risks.

Thus, shorter product cycles, technology convergence, and high R&D costs jointly drive co-opetition in high-technology industries, as evidenced in the increased prevalence of co-opetition in such contexts. Given the continued salience of these fundamental drivers, it is clear that high-technology firms that learn to effectively pursue co-opetition strategies will have greater competitive advantage in today’s globally competitive context.

Drivers, Processes, And Outcomes Of Co-Opetition Strategy

In this section, we look at the current literature on co-opetition and identify some core themes that have occupied scholars, which we cluster broadly into the three categories of drivers, processes, and outcomes of co-opetition strategy. In developing this section, we summarized the key studies, using the framework introduced earlier to identify—for each study—the type of co-opetition covered, research focus, theoretical background, and conclusions. A few key points with regard to the drivers, processes, and outcomes emerged from our survey of the extent literature, and they are discussed in the following sections.

Drivers

The key idea that Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) highlighted in their seminal book is that of co-opetition as involving value creation and value appropriation:

Business is cooperation when it comes to creating a pie and competition when it comes to dividing it up. This duality can easily make business relationships feel paradoxical. But learning to be comfortable with this duality is the key to success. (p. 259)

Similarly, Khanna, Gulati, and Nohria (1998) argued that the tension between cooperation and competition is essentially driven by the conflict between generating “common benefits” and capturing “private benefits.” The locus of co-opetition, thus, is determined mainly by the dynamic relationship between value creation and value appropriation. In other words, the fundamental reason why competitors start to cooperate or collaborators start to compete is the imbalance between value creation and value appropriation in their specific situation. Most authors have agreed explicitly or implicitly on such a rationale even though they may have different terminologies for areas of value creation vis-à-vis value appropriation based on their theoretical orientations. For instance, cooperation in value creation may take place in the input stages of the value chain (according to industrial organization [IO] economics) or the exploration phase of knowledge management (according to organizational learning theory). On the other hand, competition in value appropriation may occur in output stages of the value chain or the exploitation phase of knowledge management. In practical terms, such imbalance is reflected in resource asymmetries between rivals, which are therefore an important driver of co-opetition (Bengtsson & Kock, 1999). By extension, dynamics resource flows and differentiated structural positions in the resulting networks influence firms’ competitive behavior toward others in the network, thus forming another driver of co-opetition (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001). The nature of knowledge may also be a potential driver—Oliver (2004) argued that the tension between distributive and integrative elements of knowledge appropriation influences the balance between competition and collaboration.

In specific contexts such as high technology, there appear to be unique drivers of co-opetition seem to be short product life cycles, increasing R&D costs, and technological convergence. The S-LCD case also suggests that those factors were important in motivating rival Sony and Samsung to collaborate with each other.

From the practitioner’s perspective, the complexity of simultaneous cooperation and competition requires effective strategic planning and management. Managerial cognitive systems and firm resource profiles that can embrace divergent, seemingly conflicting orientations are more likely to engage in co-opetitive behaviors (Lado, Boyd, & Hanlon, 1997). Meanwhile, changes of institutional norms can have significant implications for firms’ behavior (Zajac & Westphal ,2004). As we remarked earlier, the notion of co-opetition has gained in popularity in the business world since the late 1990s. However, many executives still find it difficult to convince others to accept and practice collaboration with their key competitors (Coy, 2006). Therefore, as the norm of co-opetition becomes more institutionally accepted, firms are increasingly likely to switch from the competitive mentality to co-petitive mentality.

Processes

Even though cooperation and competition can “coexist,” the logics of competition and cooperation are in diametrical contrast. The complexity of managing simultaneous cooperation and competition with the same partner competitor is expected to be highly challenging, which explains the basic tendency to avoid collaboration with direct competitors. In general, the logical and mental paradoxes can be reduced or managed through (a) spatial and/or temporal separations or (b) making either the cooperation element or the competition element tacit or hidden (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Oliver, 2004).

Specifically, the generation of common benefits can take place in areas (e.g., value chain stages, geographic regions, product market segments, etc.) that are different from where collaborating firms capture their private benefits. Thus, the separation of the locus of value creation and that of value appropriation can reduce some complexity and direct conflicts. In particular, competition for value appropriation usually happens in the stages of the value chain that are close to the customers, such as product introduction and marketing, while cooperation for value creation generally takes place in the early stages of the value chain such as R&D. In the S-LCD case, for example, the two companies collaborate effectively in R&D and manufacturing while maintaining intense competition with each other in the end product market.

Also, there is a time dimension to the duality of cooperation and competition (Clarke-Hill et al., 2003). Value creation and value appropriation do not need to happen at the same time. The inherent tension and complexity with managing simultaneous competition and cooperation lead to the speculation that firms may compete more in one time period but cooperate more in another time period. In other words, co-opetition with the same partner competitor in the same value chain stage (or geographic market) at the same time might indeed be very rare, representing an “ideal type” of which only a small number of features may be present in a given situation. For example, in the S-LCD case, while Samsung and Sony have collaborated for the development and manufacturing of the LCD panels, Samsung has two of its own separate seventh generation LCD plants, thus effectively competing with the S-LCD. As illustrated in Figure 38.1, various dynamics of collaboration and competition at multiple levels are evident between Samsung and Sony, thus making the co-opetitive relationship extremely challenging for both firms and interesting from the analyst’s viewpoint.

Conflicts between competition and cooperation can sometimes become extremely severe, inducing the dissolution of balanced co-opetitive relationships. Successful learning from competitors requires effective organizational learning as well as measures of self-defense (Hamel, Doz, & Prahalad, 1989). Centralization and formal hierarchical factors impede knowledge sharing in co-opetition, while informal lateral relations promote it (Tsai, 2002). Sometimes, an intermediary organization (e.g., government authority, trade association, etc.) can play the facilitator role to ensure co-opetition relationships can be established and maintained to achieve fruitful results. Case studies of the VLSI semiconductor research project in Japan (Sakakibara, 1993) and the Finnish diary industry (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000) provide empirical support for such a suggestion.

Outcomes

The economic outcomes of co-opetition can be studied at firm, bilateral, multilateral, and industry levels. In particular, Lado et al. (1997) submitted that firms that can effectively formulate and implement co-opetition strategies with their stakeholders can achieve superior economic performance based on the combination of both competitive and cooperative advantages. Sakakibara (1993) found that clear evidence of benefits is a critical determinant of success in co-opetition, suggesting that it is important to select appropriate projects for co-opetition relationships.

Although no large-scale empirical research has been conducted to systematically examine the performance outcome of co-opetition strategy, case studies, and anecdotal experience provide support for such a proposition. For example, the S-LCD case illustrates that both Samsung and Sony have benefited greatly through their co-opetitive relationship. As illustrated in Figures 38.1 and 38.2, Samsung seems to have benefited substantially from co-opetition, as it has been able to gain market share in the LCD TV market. The S-LCD partners are ahead of the other industry players in investing in the LCD technology. So the investment gap between S-LCD and the rest of the industry has widened considerably with the new eighth generation plant (with 50,000 units per month). Sharp is the only another company that has an eighth generation plant and produces 30,000 panels per month. Outcomes of this co-opetitive relationship seem to go beyond the firms and have led to intensified battles between LCD and plasma technologies in flat screen TV. Plasma leads LCD in 50-inch or larger TV screens, but the eighth generation plant of S-LCD is challenging that. Price and size—two major considerations of the recent past—are becoming less of an issue as LCD TVs are bigger and cheaper and are really starting to compete with those of similar size plasma TVs.

It is also possible that a firm that is better prepared for co-opetition, that is, has the necessary mind-set, resources, and capabilities will benefit more from co-opetition. Firms that pursue a proactive strategy (e.g., being the first mover or a close follower in their industries), have a superior resource base (thus making them an attractive competitor partner), and have managers that can handle paradoxical approaches to management are more likely to engage in co-opetition and likely to be benefit more from co-opetition (Gnyawali & Park, 2007).

Conclusions And Future Directions

Overall, it is clear that academic research and business experience provide clear evidence of the growing popularity co-opetition. Firms in many industries, especially those in high-technology industries, need to explicitly consider co-opetition as part of their strategy tool set. In other words, just as strategists think about how to outcompete a rival in their industry (competitive strategy) and about how to pursue and manage collaborations (cooperative strategy), they need to pursue ways in which they can simultaneously engage in collaboration and competition. Many challenges remain, however, for both academics and managers. As we look forward at the future of co-opetition, we identify the following two specific questions that managers and researchers could address in the future, in the process surfacing some intriguing issues about co-opetition.

First, how do industries, firms, and managers differ in how they draw a line between collaboration and competition? Although we have made a distinction between co-opetition and collusion at the conceptual level, drawing a clear line between the two in practice can be a challenging task. At the industry level, what forces drive the parties to move from the competitive end to the collaborative end of the co-opetition continuum or vice versa? If competition is viewed as short-term fighting for a share of the pie and cooperation is viewed as longer term working together to increase the size of the pie, one way to analyze this is in terms of Axelrod’s (1984) shadow of the future. In this context, Axelrod argued as follows:

But the future is less important than the present for two reasons. The first is that players tend to value payoffs less as the time of their obtainment recedes into the future. The second is that there is always some chance that the players will not meet again . . . For these reasons, the payoff of the next move always counts less than the payoff of the current move. A natural way to take this into account is to cumulate payoffs over time in such a way that the next move is worth some fraction of the current move (Shubik, 1970). The weight (or importance) of the next move relative to the current move will be called w. It represents the degree to which the payoff of each move is discounted relative to the previous move, and is therefore a discount parameter. (pp. 12-13)

Given Axelrod’s (1984) framing of the discount parameter for future-oriented cooperation, this particular research question may be restated as the following: What are the ways in which new technologies and competitive structures may conspire to change w so as to increase the incentive to cooperate?

At other levels, some managers and firms may be more psychologically and organizationally adept at managing the dynamic tension that is at the core of co-opetition. For example, early positive experience with co-opetition may predispose firms to future collaborative efforts involving rivals. There may be cultural (at the firm, industry, and national levels) and institutional factors (e.g., antitrust framework) that influence such differences in co-opetition perceptions and skills. For example, Jorde and Teece (1990) suggested that cooperation among competitors in technological innovation might not necessarily be anticompetitive. Co-opetition might bring unique products and create new markets for them and may develop integrative technologies so that consumers can buy fewer but well functioning products. Co-opetition in standards-based industries among a group of firms may lead to group versus group competition (Gomes-Casseres, 1994), which may be even more intensified form of competition. Thus, it is possible that co-opetition to create value (or bring major new technologies and products) is not problematic, but cooperation among a set of competitors to take customers directly away from another set of competitors may be problematic. Overall, more in-depth knowledge of the dynamics of co-opetition will benefit firms who engage in co-opetition as well as policymakers concerned with balancing competition and cooperation.

From the institutional viewpoint, the antitrust framework may be a critical element in this regard. It may not be easy to define whether the value created by competitor partners through collaboration is truly based on innovation and efficiency and not based on squeezing value from other stakeholders. It is also likely that competitor partners—through intensive co-opetition—can establish tacit collusions based on increased mutual understanding of each other’s strategic intents and capabilities. In our brief discussion of the historical roots of co-opetition, we touched upon how it has influenced public policy especially in the antitrust arena. The antitrust framework in many countries is today more supportive of precompetitive collaboration (e.g., in basic R&D) than in earlier periods. For example, the U.S. Department of Justice has published guidelines for horizontal cooperation JVs. Influenced as it is by political mood and cultural context, the enforcement of antitrust laws vary from country to country, and the prevailing attitudes toward co-opetition are no exception—thus, some observers have argued that Japanese and European antitrust frameworks are more open to co-opetition than their U.S. counterpart (Jorde & Teece, 1990). As the nature and extent of co-opetition evolves over the years, antitrust policy will also need to keep pace, suggesting that co-opetition is potentially an interesting topic of study for legal scholars as well as for scholars of strategy and organization.

Second, how can parties engaged in both high competition and high collaboration simultaneously manage the paradox operationally? As managers acknowledge the importance of co-opetition strategy, they also face the challenges of managing co-opetition on a daily basis. The challenge is many-fold. At the simple psychological level, the need for cognitive balance makes it likely that demands to compete and collaborate with the same other will place an individual at risk of cognitive dissonance. Given the importance of trust in alliance relationships, this is not an easy issue to address. At the organizational level, designing appropriate processes for sharing the right type and level of information so that cooperation goals are effectively met without the loss of competitively sensitive information is not going to be easy (Madhavan, 1993). Potential solutions may involve modularly separating cooperation and competition activities, with the integration being done at the senior most levels of the organization. The cross-level implications of co-opetition (e.g., friendship ties among employees of rival firms) are also relevant here: Such a situation may simply instantiate the phenomenon of socially embedded competition, or the firm may purposefully pursue such cross-level co-opetition to its advantage. A key part of the solution is the need to develop a co-opetitive mind-set for the effective management of the paradoxical nature of co-opetition (Chen, 2007). Lado et al. (1997) clearly suggested that a top management team’s posture in promoting or discouraging employees’ co-opetitive behaviors affect the firm’s ability to engage in such behavior. Research and practice show that the way managers think and the kind of mental models managers possess greatly influence their behaviors. Therefore, it is important that executives and managers make systematic efforts to develop co-opetition mental models. Elements of such a co-opetition mental model might include recognizing the importance of co-opetition, scanning the environment for co-opetition opportunities, and developing ways to effectively engage in actual collaboration relationships with competitors.

In conclusion, this research-paper has discussed the important strategy construct of co-opetition, outlining its intellectual lineage and practical relevance. We began with a detailed illustration of collaboration between two fierce rivals, Samsung Electronics and Sony, which illustrated why firms engage in co-opetition as well as the kinds of dynamics and challenges firms face when they collaborate and compete at the same time. Next, introduced a framework for thinking about co-opetition, provided a summary of the literature and an exploration of the drivers, processes, and outcomes of co-opetition, and sketched two broad research directions that can strengthen and enrich the co-opetition construct. Thus, we hope that this research-paper has provided a concise summary of a critically important topic that is bound to assume even greater prominence as global competition intensifies in a broad range of industries and managers search for “new game strategies.”

References:

- Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

- Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (1999). Cooperation and competition in relationships between competitors in business networks. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 14(3), 178-193.

- Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2GGG). “Cooperation” in business networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411-427.

- Brandenburger, A. M., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday.

- Carayannis, E. G., & Alexander, J. (1999). Winning by co-opetiting in strategic government-university-industry R&D partner-ships: The power of complex, dynamic knowledge networks. Journal of Technology Transfer, 24(2-3), 197-21G.

- Carayannis, E. G., & Alexander, J. (2GG4). Strategy, structure, and performance issues of precompetitive R&D consortia: Insights and lessons learned from SEMATECH. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 51(2), 226-232.

- Chaudhri, V., & Samson, D. (2GGG). Business-government relations in Australia: Cooperating through task forces. Academy of Management Executive, 14(3), 16-29.

- Chen, M. J. (in press). Reconceptualizing the competition-cooperation relationship: A transparadox perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry.

- Chien, T. H., & Peng, T. J. (2GG5). Competition and cooperation intensity in a network—A case study in Taiwan simulator industry. Journal of American Academy of Business, 7(2), 150-155.

- Clarke-Hill, C., Li, H., & Davies, B. (2003). The paradox of cooperation and competition in strategic alliances: Towards a multi-paradigm approach. Management Research News, 26(1), 1-20.

- Coy, P. (2006, August 21-28). Sleeping with the enemy. Business Week, pp. 96-97.

- Dvorak, P., & Ramstad, E. (2006, January 3). TV marriage: Behind Sony-Samsung rivalry, an unlikely alliance develops electronics giants join forces on flat-panel technology; Move prompts complaints. Wall Street Journal, p. A1.

- Garud, R. (1994). Cooperative and competitive behaviors during the process of creative destruction. Research Policy, 23(4), 385-394.

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Madhavan, R. (2001). Cooperative networks and competitive dynamics: A structural embeddedness per-spective. Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 431-445.

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Park, B. J. (2007). Co-opetition for technological innovation: An in-depth exploratory study. Proceedings of the 2007 International Conference of the Strategic Management Society.

- Gnyawali, D. R., He, J., & Madhavan, R. (2006). Impact of co-opetition on firm competitive behavior: An empirical examination. Journal of Management, 32(4), 507-530.

- Gomes-Casseres, B. (1994). Group versus group: How alliance networks compete. Harvard Business Review, 72(4), 62-71.

- Hagedoorn, J., Carayannis, E., & Alexander, J. (2001). Strange bedfellows in the personal computer industry: Technology alliances between IBM and Apple. Research Policy, 30(5), 837-849.

- Hamel, G., Doz, Y. L., & Prahalad, C. K. (1989). Collaborate with your competitors—and win. Harvard Business Review, 67(1), 133-139.

- Harbison, J. R., & Pekar, P., Jr. (1998). Smart alliances. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ihlwan, M. (2006, November 26). Samsung and Sony’s win-win LCD venture [Electronic version]. BusinessWeek.com. Retrieved September 10, 2007, from http://www.businessweek. com/globalbiz/content/nov2006/gb20061128_546338. htm?chan=search

- Ingram, P., & Roberts, P. W. (2000). Friendships among competitors in the Sydney hotel industry. American Journal of Sociology, 106(2), 387-423.

- Jorde, T. M., & Teece, D. J. (1990). Innovation and cooperation: Implications for competition and antitrust. The Journal of Economic Perspective, 4(3), 75-96.

- Khanna, T., Gulati, R., & Nohria, N. (1998). The dynamics of learning alliances: Competition, cooperation, and relative scope. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 193-210.

- Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Hanlon, S. C. (1997). Competition, cooperation, and the search for economic rents: A syncretic model. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 110-141.

- Leifer, E. (1991). Actors as observers: A theory of skill in social relationships. New York: Garland.

- Luo, X., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pan, X. (2006). Cross-functional “co-opetition”: The simultaneous role of cooperation and competition within firms. Journal of Marketing, 70(2), 67-80.

- Luo, Y. (2004a). Co-opetition in international business. Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Luo, Y. (2004b). A co-opetition perspective of MNC-host government relations. Journal of International Management, 10(4), 431-451.

- Luo, Y. (2005). Toward co-opetition within a multinational enterprise: A perspective from foreign subsidiaries. Journal of World Business, 40(1), 71-90.

- Lynn, G. S., S Akgün, A. E. (1998). Innovation strategies under uncertainty: A contingency approach for new product development. Engineering Management Journal, 10(3), 11-17.

- Madhavan, R. (1993). Managing bleedthrough: The role of the CI analyst in strategic alliances. In J. E. Prescott S P. Gibbons (Eds.), Global perspectives on competitive intelligence (pp. 243-259). Alexandria, VA: Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals.

- Madhavan, R., Gnyawali, D. R., S He, J. (2004). Two’s company, three’s a crowd? Triads in cooperative-competitive networks. Academy of Management Journal, 47(б), 918-927.

- Oliver, A. L. (2004). On the duality of competition and collaboration: Network-based knowledge relations in the biotechnology industry. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 20(1-2), 151-171.

- Oxley, J. E., S Sampson, R. C. (2004). The scope and governance of international RSD alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 25(8-9), 723-749.

- Poole, M. S., S Van de Ven, A. H. (1989). Using paradox to build management and organization theories. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 5б2-578.

- Quintana-Garcfa, C., S Benavides-Velasco, C. (2004). Cooperation, competition, an innovative capability: A panel data of European dedicated biotechnology firms. Technovation, 24(12), 927-938.

- Sakakibara, K. (1993). RSD cooperation among competitors: A case study of the VLSI semiconductor research project in Japan. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 10(4), 393-407.

- Tsai, W. (2002). Social structure of “co-opetition” within a multi-unit organization: Coordination, competition, and intra-organizational knowledge sharing. Organization Science, 13(2), 179-190.

- Von Hippel, E. (1987). Cooperation between rivals: Informal know-how trading. Research Policy, 16(б), 291-302.

- Zajac, E. J., S Westphal, J. D. (2004). The social construction of market value: Institutionalization and learning perspectives on stock market reactions. American Sociological Review, 69(3), 433-457.

- Zineldin, M. (2004). Co-opetition: The organization of the future. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22(7), 780-789.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.