This sample Entrepreneur Resilience Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

We shall finally try to round off our picture of the entrepreneurship in the same manner in which we always, in science as well as in practical life, try to understand human behavior, viz. by analyzing the characteristic motives of his conduct. Any attempt to do this must of course meet with all those objections against the economist’s intrusion into ‘psychology’ which have been made familiar by a long series of writers . . . There may be rational conduct even in the absence of rational motive. But as soon as we really wish to penetrate into motivation, the problem proves by no means simple. —Joseph A. Schumpeter, 1883-1950

The leaders I met, whatever walk of life they were from, whatever institutions they were presiding over, always referred back to the same failure—something that happened to them that was personally difficult, even traumatic, something that made them feel that desperate sense of hitting bottom—as something they thought was almost a necessity. It’s as if at that moment the iron entered their soul; that moment created the resilience that leaders need. —Warren G. Bennis, b. 1925

This research-paper will discuss the factors that lead some entrepreneurs to keep trying until they succeed in business rather than being deterred by earlier failure. Examples will be provided from Taiwanese entrepreneurs to illustrate concepts. Entrepreneurs are active dream makers and exploiters of opportunities in diverse areas including intrapreneurship, markets, and even social and political work. In the process of starting up new businesses, entrepreneurs explore business potential based on their visions of how the future will turn out, and how they expect their own business identities to form. In order to realize value, entrepreneurs create new organizations, in turn adding competition for their industries. Their work often results in economic growth in the forms of an increase in jobs, an elevated technological horizon, and social wealth and renewal (Bednarzik, 2000; Drucker, 1985). While entrepreneurs invest with prosperous intentions, they also risk failure since entrepreneurship a demanding activity embedded in complicated contexts (Brockhaus, 1980; van Gelderen, Thurik, & Bosma, 2006). Therefore, many entrepreneurial organizations emerge and then disappear within a short, incomplete life cycle.

For a new enterprise to succeed, human capital performance can be key (Hayton, 2004). Moreover, it influences business viability and longevity (Bates, 1985, 1990). To a large extent, the success or failure of a venture depends on the entrepreneur, and he or she expects some reward due to his or her willingness to undertake risk (Cunningham & Lischeron, 1991). An entrepreneur must deal with the scrutiny of financial institutions through the process of soliciting capital and feedback. Pressure, which may result in positive consequences (constructive pressure) or negative consequences, may accompany the expected returns from the entrepreneurial process. The soundness of an entrepreneur’s plan and his or her marshalling of the capabilities and resources needed to make the venture a success are reflected in the assessment of financial institutions and their willingness to fund the venture.

A “resilient mind-set” (Brooks & Goldstein, 2003), whether in terms of social life or organizational life, is an especially strong driver for entrepreneurs when facing business failure, sometimes serially. It also enables the expression of originality. Thus, an entrepreneur’s willingness and ability to recover from and respond to the challenges involved in the construction of a venture may not merely indicate a propensity for seeking new business opportunities but may also serve as an antecedent for predicting new business success. According to Aldrich (1999), over 50% of new ventures are terminated quickly after they are developed. Hence it is important to study the postfailure dynamics of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneur resilience could be defined as the inclination by which entrepreneurs reengage in entrepreneurship after venture failure(s). In such periods, the entrepreneur strives to adapt toward a healthier mindset and sounder capability, while facing the adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or other sources of stress from the failure(s) (Envick, 2004; Smokowski, Reynolds, & Bezruczko, 1999).

Entrepreneurial studies have been performed in the context of several schools of thought, such as Great Man, Psychological Characteristics, Classical (Innovation), Management, Leadership, and Intrapreneurship (Cunningham & Lischeron, 1991). Beyond attributing individual resilience to intrinsic factors including personality, courage, and others from the intuitive psychology discipline (e.g., Bonanno, 2004), the discussion of entrepreneurial resilience should be extended to attribute individual resilience to motives and capabilities which rely on the concrete managerial abilities and social contexts offering entrepreneurs the foundations for resilience. While personal traits of entrepreneurs have become instrumental for explaining entrepreneurial activities, other factors also hold influence. The imperatives for personal and organizational value creation in a modern economy have been slighted and are in need of further study. Surprisingly, the issues concerning entrepreneur resilience have received little research attention.

Accordingly, this research-paper prepares to uncover some of the influencing factors that motivate and support entrepreneurs’ return to venture excellence after venture failure(s).

In this research-paper, first we review the literature concerning entrepreneur resilience. Next, we explore the influencing factors for entrepreneurs’ resilience using a multilevel framework that considers current knowledge and social aspects of entrepreneurs’ lives. To clarify the framework, woven throughout the discourse are illustrative cases that offer the reader a vivid experience through stories. Finally, concluding remarks are offered, leading to implications and possible future research directions.

Entrepreneur Resilience

Resilience theory originated from pressure adjustment in psychotherapy. The theory explores how individuals deal with crises, and how crises may enhance an individual’s ability (Rak & Patterson, 1996). Each person has an innate ability to rebound, but this certainly does not mean a person will not experience difficulties or feel depressed when facing a rebound experience (APA, 2002). Resilience should not be understood as overcoming difficulties easily or not suffering from crises. The focus should not rest solely on the “bounce back,” but also on an individual’s struggle in difficult situations and the courage that an individual shows in such a struggle with adversity (Bonanno, 2004). In fact, any one resilience theory or model is not applicable in all circumstances; rather, resilience depends on the interaction between the individual and environment (Rutter, 1993).

Generally, resilience is a power or an energy that determines how people overcome great adversity, stress, or unexpected results of human actions (Brooks & Goldstein, 2003). Different scholars have different points of view on resilience, primarily about whether it is internally or externally mechanized. Scholars from the “inner protection mechanism” viewpoint advocate that individual characteristics such as hardiness, optimism, good interpersonal relationships, and self-reinforcement can reduce the influence of any crisis (Garmezy, 1985). These characteristics can reduce misbehavior (Smokowski, Reynolds, & Bezruczko, 1999), increase successful adjustment (Benard, 1996; Sagor, 1996), enhance the skills for dealing with crises, and develop the ability to solve problems.

Scholars of the “external protection mechanism” viewpoint believe that resilience is how an individual learns to achieve a goal through interaction with the environment; the individual adjusts the environment to avoid collapse (Holaday & McPhearson, 1997). Still other scholars believe that resilience should be discussed based on its eventual results. From this point of view, resilience refers to the ability to overcome difficulties and perform better than expected (Richardson, 2002). During the process of struggling with adversity and overcoming difficulties, an individual may obtain more resources necessary for success and further develop the ability to bounce back. Over time, a person with a comparative lack of resilience will likely develop greater overall resilience than a person who initially possessed more resilience. Therefore the person with the initially lesser level of resilience will obtain greater benefits from adverse experiences.

In recent years, researchers in business administration have been studying resilience after business failure as different from other general trauma experienced in life. Researchers are trying to explain why some entrepreneurs are able to overcome obstacles after a setback while others are unable to recover. Most entrepreneurs dedicate themselves to their businesses. The failure of their enterprises could lead to them losing their property and social status. Not all entrepreneurs are optimistic and have the courage to manage crisis; they have negative feelings (Coutu, 2002) such as helplessness, distrust, and defensiveness, and they exhibit irrational behaviors (Kets de Vries, 1985). Little study has been conducted on how entrepreneurs recover after setbacks.

We define resilience as the process of an entrepreneur’s recovery from a setback, and subsequent reinstatement. In such a process, entrepreneurs develop their managerial skills and learn techniques to reduce the risk of further setbacks, thereby increasing their chances of success (or at least to decrease their chances of failing again) in the future. The purpose of studying resilience is not limited to understanding entrepreneurs’ ambitions and motivations to bounce back successfully, but also to explore how they rebuild their enterprises.

Multilevel Influential Factors For Entrepreneur Resilience

An entrepreneur, noted Ryans (1997), is one who “combines the conversion of ideas into a viable business through ingenuity, hard work, resilience, imagination, [and] luck” (p. 95). As Shapero (1981) noted, entrepreneurs play an important role in a buoyant economic environment because of their self-renewal capacity. For entrepreneurs to operate, they must do so in a uniquely complex environment, which can be seen as a nested, multilevel system of innovation. On the one hand, a resilient entrepreneurial environment needs resilient entrepreneurs who take initiative for individual and collective goals. On the other hand, such an environment involves many factors which influence each entrepreneur’s level of resilience. In other words, entrepreneurial surroundings not only depend on potential entrepreneurs, but also nurture entrepreneurs’ potentials (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994).

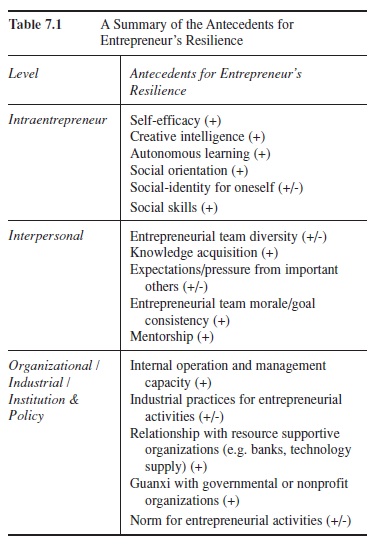

Table 7.1 A Summary of the Antecedents for Entrepreneur’s Resilience

Table 7.1 A Summary of the Antecedents for Entrepreneur’s Resilience

In the following, we comprehensively review the potential antecedents for an entrepreneur’s resilience. Furthermore, we examine whether these antecedents serve as drivers and/or impediments, with positive and/or negative influences. Table 7.1 presents a summary of the factors which will be discussed in this research-paper. Within the research-paper, a subheading for each antecedent is shown with a positive and/or negative sign indicating our preliminary opinion as to which direction(s) of influence each antecedent has on entrepreneur resilience. Future studies are encouraged to examine the proposed influences more extensively, particularly the posited directions of influence, based on deductive or inductive approaches for theory building.

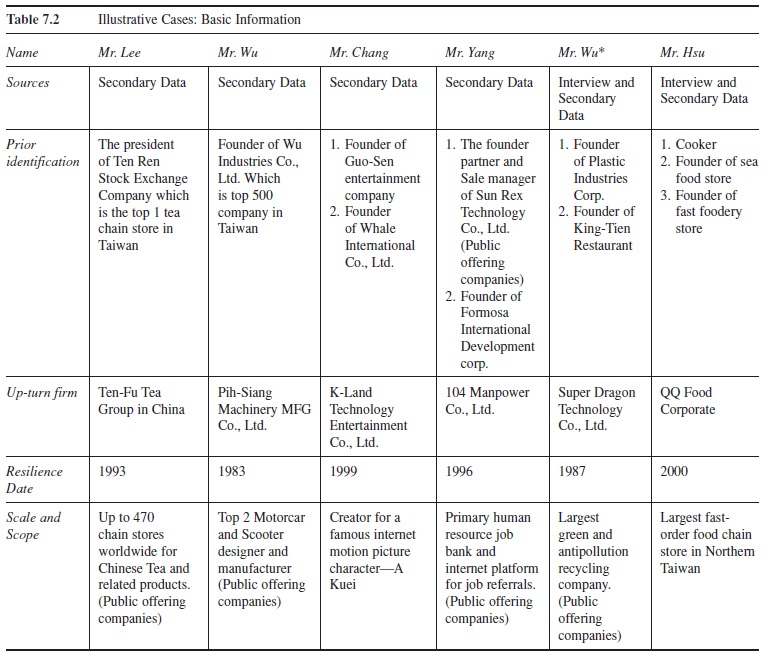

In order to offer cohesive associations between theoretical articulations and authentic experiences, illustrative examples are incorporated in our research-paper. Some examples were extracted from interviews conducted by one of the authors. Others were drawn from secondary resources, including newspapers and business magazines containing entrepreneurial narratives or stories (e.g., Business Weekly, Common Wealth Magazine, etc.) The illustrative cases concern well-known entrepreneurs in the greater China region. Table 7.2 outlines biographical information about these (resilient) entrepreneurs. Since the primary intent of this research-paper is to explore theoretical constructs for future studies to consider, our approach is scientifically grounded on entre-preneurs’ lives; after all, business itself is an entrepreneur’s life (Yin, 1994). In the lives of our example entrepreneurs, respective businesses are the major themes. By using this conceptualized knowledge approach, researchers, students, and practitioners who are generally interested in this topic will also benefit.

Table 7.2 Illustrative Cases: Basic Information

Table 7.2 Illustrative Cases: Basic Information

Intraentrepreneur Level

Self-Efficacy (+)

When people think they can handle complex challenges well, they are not only more capable of accomplishments, but they are also more self-confident (Bandura, 1977, 1997). According to Bandura (1986), “self-efficacy” refers to a judgment of oneself in terms of an ability to realize perceived resources and controls. In particular, this realization is judged when a person has to conduct a series of actions to complete some specific goal. Increased goal clarity is also closely related to high self-efficacy (Erikson, 2002). If an entrepreneur realizes that he or she possesses a certain degree of resources and knowledge which can help fulfill the planned objective, his or her motivation is higher and he or she is more likely to be motivated by the thought of reentry into building a new business. As Wu* (personal communication) said in an interview,

I was depressed at that time. I am professional and I know how to make four or five hundred out of a hundred. I had to give my company to Super Dragon. I know I had to endure. I have to treat that as tutoring and an opportunity to learn their refining technology. I must have to run my business day-to-day.”

Wu* started a recycling business, but he had to deal with environmental protection legal problems between Japan and Taiwan. The situation strengthened his resolve to start a refining recycling business by himself.

Creative Intelligence (+)

The business environment is changing rapidly, so the ability to think creatively has become important in management settings (Sternberg, 2003). Entrepreneurs shatter the status quo through new combinations of resources and new methods of commerce (Holt, 1992). Creativity is an ability to bring something new into existence; this definition emphasizes the ability of an individual to generate fresh variations rather than the actual generation of such results (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996). Accordingly, entrepreneurs with creative intelligence refer to their insights and use their abilities to uniquely react to novel situations and stimuli (Sternberg, 1985).

Highly creative individuals often apply existing knowledge to new problems, moving from conventional learning to new learning in a different situation. In such ways they can originate cognitive shifts (Sternberg, 2003). Through this process, entrepreneurs invest in ideas that often have latent growth potential but are otherwise currently unknown, unpopular, or perceived to be of low value. Entrepreneurs renovate prospective ideas and sell them to whoever is able to afford paying for the higher value of novelty; this is known as the “renowned investment theory of creativity” (Sternberg & Lubart, 1995). Moreover, persistence, curiosity, energy, and honesty are important properties of creativity and each is fueled by intrinsic motivations (Amabile, 1988). Positive evaluation has a positive effect on self-efficacy and as a result enhances the creativity of a performance. Furthermore, the choices involved in how to perform a task can enhance a person’s intrinsic interest and creativity.

Entrepreneurs with creative intelligence are capable of analyzing the relevant aspects of the situation without being distracted by the irrelevant aspects. Thus, a person’s disposition toward intellectual transformation is a general cognitive style dimension and, accordingly, both domain-specific skills and creativity-specific skills are imperative to creativity (Amabile 1988). A famous story of bouncing back by utilizing personal creativity is that of a famous Web animation producer named Chang.

Chang designed a comic character “A-Kuei” based on his childhood. The success of A-Kuei skyrocketed his professional career as a director. A-Kuei soon became very popular throughout the Internet (Jn, 2000).

When Chang was in the nadir of his career, he saw an opportunity to creatively use his expertise and intelligence to reverse his situation. Another story from a Medical Motor merchant, Wu, illustrates this:

Wu loved the sensations of nature ever since he was little. When he was in elementary school he was curious about how birds and dragonflies could fly. He used wood, cans, and steel wire to make toy cars. He made a radio and sold it to a friend when he was fourteen. After that, he studied at Pingtung Institute where he continued to love investigating all kinds of equipment. He built a motorcycle and then used it to make a living (Public TV, 2004).

Leaders bring their creative thinking skills into the practice of idea generation using feedback from followers. Unsurprisingly, rewards are necessary for better creativity performance (Sternberg, 2003). Successful entrepreneurs are willing to bear the risks of investing in creativity, making decisions under uncertainty, and redefine problems in uncommon ways. This means entrepreneurs “buy low and sell high” in terms of investing in creativity provisions that may well propel the venture into superior returns.

Autonomous Learning (+)

Some researchers argue that previous experience and prior learning have not just positive but also negative effects on creativity (e.g., Stein, 1991). Previous experience or knowledge may lead to a functional silo mentality that prevents individuals from producing creative solutions. Yet nothing can be made of nothing. Entrepreneurs need to introduce variation, such as trying various combinations to acquire new knowledge of what works and what does not (Campbell, 1960).

Learning is a way for both individuals and organizations to update their respective portfolios of capabilities. This is especially important for entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial learning, especially double-loop learning (Sullivan, 2000), is critical for entrepreneurial development; it is essential when correcting weaknesses and dealing with failures (Politis, 2005).

Wu would buy products from a company which was closing down and find out why the company was going out of business. “I would analyze the products and its sales systems so as not to make the same mistakes. Besides, safety is very important for a Scooter, so I have to pay great attention to that,” Wu said in a TV interview (Public TV, 2004).

In this vein, a person employing self-activated learning is able to reorganize existing knowledge materials and to integrate them into meaningful memories according to changing conditions or dynamic events. Argyris and Schon (1978) argue that such learning is a process of detecting and correcting errors. For entrepreneurs, reflection serves not only to identify facts, but also to instill findings and observations into future business blueprints. These two entrepreneurs’ narrations demonstrate this point:

Hsu is continuing to take all kinds of training courses to strengthen his abilities. “I didn’t read much before, but in order to manage the company, I am taking courses in management, interpersonal relationships, and communication skills,” Hsu (personal communication) said in the interview.

Wu* endured unfair charges for about three or four years from the Japanese, while keeping good relationships with them, so that he could learn the techniques from them. Wu* also learned techniques from Americans and Europeans. He imported equipment from Germany and Japan to build his own gold-refining techniques. “I still think that I have to do the recycling and refining business by myself; that is the value. Why do I have to bear high charges? It’s unreasonable. I am forced to handle things myself,” Wu* (personal communication) said in his interview. Therefore, he started to work with the Technology Institute to build his own system.

Social Orientation (+)

Social motives are related to a certain degree with actual behavior (Liebrand & Godfried, 1985). A high degree of social orientation means that a person is active, externally searching, nonexploitive, and participative when taking initiative or planning a series of actions. Diekmann and Lindenberg (2001) suggest that individuals are differentiated according to their orientation toward others. This orientation is often assumed to be more or less stable and the joint result of nature and nurturing. Different types of orientation exist with the following three most frequently identified: “cooperative” (the goal is to maximize joint payoffs), “individualistic” (the goal is to maximize individual payoffs), and “competitive” (the goal is to maximize the positive difference between one’s payoff and another’s). All of these orientations suggest an intuition to do something beneficial in the future. Wu* (personal communication) expressed in the interview,

I communicated several times with my partner when I knew he was not disclosing recycling techniques. At that time, I deeply knew I could not carry on any longer. So I consulted with a professional to gain an understanding of the hardware recycling process and techniques, and made up my mind to persevere and do the recycling business.

Among the three most commonly noted intuitions, a cooperative orientation with the outer social world is most beneficial for initiatives that need intricate coordination of diverse inputs. As such, people with prosocial attitudes regarding ideas or idea achievement are more willing to establish a way of doing business, thereby transforming ideas into practice.

Social Identity for Oneself (+/-)

An entrepreneur’s reputation and image influence how constituents perceive the entrepreneur’s legitimacy and trustworthiness (Ostgaard & Birley, 1996; Starr & MacMillan, 1990). From the entrepreneur’s own perspective, self-identity, or viewing oneself as an important ego in society, is also an important factor that stimulates one’s motives toward doing something “more,” not only for personal success but also to make a contribution to the larger social or business fields. Goldsmith, Veum, and Darity (1997) indicate that this psychological stimulus could influence a person’s productivity after experiencing difficulties. When entrepreneurs have a sense of responsibility, they think they should do something self-fulfilling as a piece of the greater whole.

Yang founded a computer company with friends in 1992. He worked as deputy general manger. The sales were increasing, but Yang was beginning to question the value of his work. Besides that, Yang and his partner could not agree about product quality; he decided to leave the company in 1993. Yang had to face the challenge of losing his job at the age of 34 (Yang, 2002).

Yang started to think about the value of his life, and what he could do for society. He wanted to invent something that could benefit society, such as a chemical sensor or microwave detector, but he gave up after preliminary research.

Yang argued that in Taiwan people do not have enough space to do what they would like to do. Job descriptions are fixed and not negotiable. He proposed a more flexible employment plan to help people find jobs they like. Yang said that he is not working for money but for self-fulfillment. “I want to spend my time and effort on things that are worthwhile to do. This enables me to transcend myself and muster courage and persevere,” Yang said in a media interview (Tang, 2004).

Social Skills (+)

Social skills enable entrepreneurs to induce cooperation from others in order to produce, contest, or reproduce a given set of rules (Fligstein, 1990). Likewise, when identifying opportunities for strategic initiatives, social skills aid entrepreneurs getting buy-in and effort to move on those initiatives from others. Replete with irrational actors, business requires particular attention to mobilizing personnel creatively rather than merely manipulating financial incentives (Hung, 2002).

Wu* aggressively reduced the technological capability gap with the people he knew. “He has his way, such as to get help from the Japanese and Germans,” said Mr. Lin (personal communication), Wu*’s executive assistant manager.

As these cases imply, many entrepreneurs are not initially properly teched-up. Those who are good at social or interpersonal negotiations may find that this skill assists them in surmounting any deficits in their business foundation. When this is the case, the probability increases that an entrepreneur feels more intent and possesses more ability to restart his business.

Interpersonal Level

Entrepreneurial Team Diversity (+/-)

Teams are now seen as one of the best designs for task units to survive and succeed in the modern business world. A team can achieve the flexibility and efficiency necessary while retaining the functionality required for performing organizational and knowledge-oriented tasks (Lagerstrom & Andersson, 2003). Indeed, value-creating imperatives like entrepreneurial activities are especially knowledge and innovation oriented. Heterogeneous teams can gain access to differentiated knowledge and resources and thus enrich the team’s knowledge base regarding entrepreneurial work. Having somewhat diverse entrepreneurial teams enhances each team member’s motivation and capability for facing future challenges. While the previously mentioned Flash Web-movie producer Chang utilizes his intelligence, he still needs a good group to support his creativity.

K-land emphasizes a platform for innovation management, not just the CEO’s [the founder entrepreneur’s] individual creativity.

I encourage my employees to develop a style of their own; I told them not to copy from others. Trying things differently! You have to be yourself to earn respect and have your own style be recognized. We create a business for the dreamer. (Yang 2002)

Nevertheless, just as Tsai (2005) demonstrated, team diversity affects a team’s knowledge-work outcomes. Reagans and Zuckerman (2001) argue that while diverse knowledge and wide access to resources can enable multiple and nonredundant idea generation, a diverse set of sources may also result in communicative and decisional inconsistencies and conflicts. Ultimately, diversity and similarity should be balanced on an entrepreneur’s team.

Knowledge Acquisition (+)

Often entrepreneurial knowledge is tacit (that is, unconscious). Therefore, effective knowledge acquisition often must be obtained through frequent interpersonal interactions (Nonaka, 1994; Yli-Renko, Autio, & Sapienza, 2001; Zahra, Kuratko, & Jennings, 1999).

At one time, Hsu faced a business obstacle.

I hesitated for about four months, during which time I discussed my ideas with friends, then I decided to open a new type of store. I had some new ideas then Taking account of my capabilities, I decided to initiate a buffet in Taipei Country. I always enjoyed looking for new locations. (Hsu, personal communication)

Hsu found that he learned a lot from his friends in a social network.

Several members of the Chain Store Association, including myself, formed a club. We invited experts and entrepreneurs to give speeches and training courses for sharing market information and professional management skills which strengthen our operating capabilities. (Hsu, personal communication)

Tacit knowledge is often valuable and yet hard to transfer (Szulanski, 1996). Those who manage to gain access to such knowledge may outperform others in innovation speed as well as distinctiveness in expertise. As a result, more knowledge sharing or knowledge acquisition enhances motivation and capability for entrepreneurs when they consider building a business after a prior failure.

When Wu* decided to start his own business, his friends in the chemical industry and those with prior restaurant business experience provided him with some valuable information.

Expectations/Pressure From Important Others (+/-)

People continuously imagine what is in other people’s minds, especially regarding what others think of their progress. When people feel that there is considerable distance between “what other people expect them to do” and “what they are doing currently,” they may consider filling the gap. For example, if an entrepreneur thinks that others perceive him as one who seldom fails in business, the entrepreneur would seek to quickly change by filling the gap, thereby positioning himself as one who never fails—indeed, one who even abhors the possibility of failure. In this example, said entrepreneur changes his own behavior, and current state, to fit others’ expectations.

Expectations from others, especially from important others (e.g., family, close friends, business partners), have continual impact on individual decisions and actions. As people plan their careers, they decide what they should do using social desirability as a frame of reference (Ellingson, Smith, & Sackett, 2001). For resilient entrepreneurs, such a decision may be heavily influenced by others’ expectations (or pressure). Others’ expectations highly influence an entrepreneur’s motivation to come back (or not) and his subsequent approach to building another business. Furthermore, a vote of confidence from an important other often results in self-actuated behaviors and outward signals. The former stock market exchange-company tycoon, now the most famous tea business owner in the greater China area, Lee, experienced such a process.

Lee sold his property and stocks when the crisis happened to remedy the financial deficit and investors’ losses. He also resigned from the company, walking away from his responsibility. After two years, Lee decided to seek financial support from his friends and start a new business in China. But many of his friends were unable to help him financially. Besides, his family thought that it was too risky to do business in China and did not support his decision. “It’s quite different than before and hard to fund (Tsai,2002).

Entrepreneurial Team Morale/Goal Consistency (+)

In a study investigating the conflict between a venture capitalist and an entrepreneurial team, Higashide and Billey (2002) showed that while conflict and disagreement can be beneficial for venture performance, conflict based on personal friction is negatively associated with performance. The impact is generally stronger for conflicts related to organizational goals than those related to policy decisions. Especially in early stages of a business, goals of consistency and interpersonal solidarity are important. Inconsistency may lead to negative consequences. For instance, an idea champion (often the entrepreneur) may try to convince the team to achieve a “preferred” agreement. Once team members support the entrepreneur’s proposed blueprint for a new business and when the strategic direction is clearly set, actions to accomplish the objective are more likely to be performed and the business will be running better than would otherwise be feasible.

His export business did not go well; therefore, Lee decided to do domestic trading. His employees were against this decision. They were afraid that his company could not compete with others. Lee believed that his company could beat others with better quality and service. Finally, Lee transferred the Taiwanese Ten-Ren Chain store system to the China market for domestic market development (Tsai, 2002).

There may still be other situations where communication and coordination between the entrepreneurial team members proves ineffective. One of our illustrative cases indicates that cooperative partners sometimes consider terminating either a planned venture or a partnership to establish a business on their own, thus sidestepping the potential costs of coordination and conflict associated with shared management. In this way, inherently limited energy and resources might contribute more efficiently to core business activities.

After a time of cooperation, Wu* had problems with his partner. “He had an attitude problem. He always woke up at 3 o’clock in the morning to refine gold and kept the technology a secret,” Wu* (personal communication) explained. The communication between Wu* and his partner was ineffective and they were not able to work together anymore. Therefore, Wu* decided to end the business with his partner and started a new business of his own.

Mentorship (+)

Often a mentor plays a role not only as a teacher but also as a conduit for resource access. Knowledge regarding entrepreneurial activities, unknown channels for approaching opportunities and constituents, and even concrete financial support may be transferred from the mentor to the entrepreneur in a structured or semi structured way. One case source demonstrates this clearly:

Hsu received help from several friends who acted as mentors. They influenced Hsu’s attitudes about life and his business viewpoint.

I always have to express my appreciation to three people for giving me social resources. One is my brother, who runs a breakfast shop and helped my whole family to not starve when I was mired in business failure. He also taught me the concept of [stop-loss bottom-line]. Another is a CEO of a famous breakfast restaurant chain, who imparted his business experience to me. That improved my management skills. The last is the most important person to me. He is the CEO of Architecture Company. I was his first apprentice. He taught me how to build and preserve human relationships and management systems, and how to treat my employees. I always accepted his suggestions and applied them to my business and life. (Hsu, personal communication)

As we can see, Hsu gained something more than simple knowledge from his mentors.

A mentor’s guidance can be a rich knowledge environment nurturing an entrepreneur’s progress. Valuable knowledge gained from an entrepreneurial mentor facilitates the effectiveness of what Politis (2005) calls the three processes of learning. First is the entrepreneur’s own career experience, and next is the entrepreneurial transformation process. Third is entrepreneurial effectiveness in using knowledge to recognize and act on entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurial effectiveness also includes being able to cope with the liabilities of newness. With this sort of assistance, entrepreneurs can feel more confident and knowledgeable when restarting a new business since the mentor provides an accessible role model while the entrepreneur is pursuing business excellence.

Organizational/Industrial/ Institution and Policy Level

Internal Operation and Management Capacity (+)

Wu was once betrayed by a close friend and that betrayal caused his business to go bankrupt. Therefore, he does not recruit friends or relatives.

That was a painful lesson; I learned that a good management system is important to a company, no matter how excellent your business and R&D capabilities. Thus, I have been improving the management system since I started the company. I have to establish perfectly integrated management rules. (Public TV, 2004)

A resilient entrepreneur has to address more than just motives. Rather, management capacity is highly related to how resilient motives can be directed into long-lasting growth and performance. When an entrepreneur is considering the possibility of committing himself to a new business, he needs the drive to promote innovation and the capability to accept personal responsibility. Having these allows for the creation of a venture which is able to achieve a high level of performance. Since a business needs to be well founded, coordinated, and controlled, managerial regulations and capabilities become critical from the bottom levels of a company to its top strategic levels (Jones, 2000). After all, a state of idle management capacity can have tremendous negative influence on the feasibility of entrepreneurial innovations and the business’ potential for growth (Penrose, 1959). This is clearly exemplified in the following case:

“Running Yusun the tea plantation was more difficult than I imagined. The hygiene and equipment were inadequate enough. Besides, the alkalescence of the soil was unsuitable for growing tea.” To improve the chance for his bounce-back for shop production in China, Lee spent a lot of money to upgrade the equipment, and found experts and tea farmers who came from Taiwan to teach his employees how to cultivate and grow tea (Tsai, 2002).

Through training, Lee changed the employees’ attitudes toward working. His employees were asked to wear uniforms and live in the dorm. To provide better service, his employees also had to learn how to drink tea so they could teach customers tea-tasting skills, thus changing the ways of tea store promotion in the chain (Tsai, 2002).

Industrial Practices for Entrepreneurial Activities (+/-)

Most individuals have some knowledge that is not easily transferable to others in any specific time and place. Examples of such tacit knowledge may include the ability to recognize certain patterns in market behavior, subtle differences in the quality of goods, or ways to identify whether resources are being used efficiently (Holcombe, 2003). This indicates that one may apply the same approach in doing business as another but have differing perceptions of the utility of that approach. Still, the one who is trying to search for and identify new business opportunities observes the existing approach very carefully. The best practice of a new business is to demonstrate its ability to follow a proven model of business. When an entrepreneur finds that his business is stabilized at a particular level, he may wonder whether it is possible to reach a higher level of success, perhaps becoming the benchmark of best practice in his industry.

Another possibility is that an entrepreneur considers current practices in an existing market to be lacking and might become motivated to find a better approach and create a new business to implement it, perhaps garnering a higher rate of return than others. We can see an example in the following:

Wu was a supplier to the medical care industry. He noticed that three-wheeled vehicles for use in medical care applications had drawbacks that a four-wheeled model might overcome. Also, he noticed that automobile firms seemed disinterested in upgrading such vehicles. He felt confident that he might create a product better aligning with the healthcare industry’s requirements.

Relationship With Resource-Supportive Organizations (+) (e.g., Banks, Technology Supply)

A firm’s unique value and competitiveness may reside in its relationships with other organizations (Dyer & Singh, 1998). Resources from the firms in an organization’s network might be included in the estimation of its competitive advantages (Lavie, 2006). In an entrepreneurial context, external relationships with other firms can importantly affect key entrepreneurial activities such as venture formation and financing (e.g., Larson & Starr, 1993). For entrepreneurs, building business relationships and having a network of other constituents in the business environment is a common practice. This argument is especially applicable for the entrepreneurial community and organizations in an economy of network constellations (Nijkamp, 2003).

Birley (1985) clarified the different networks entrepreneurs have relationships with and separated them into formal and informal ones. Resource access is one factor used to distinguish the formal from the informal networks. Linkages to resource-supportive organizations, such as banks, technology firms, prior or potential suppliers, and research institutes, can help entrepreneurs gain access to the resources they need to run their businesses (Birly, 1985; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000). This is essential because according to Baum, Calabrese, and Silverman (2000) entrepreneurial firms are commonly lacking more resources than established firms. Therefore, if an entrepreneur has functioning relationships with others who are in possession of resources, he may have better chances and more ability to mobilize those indirect resources.

Wu was working hard to produce a good product. When his company’s capital was increased, Chung-Hung Motors became a major stockholder. Chung-Hung Motors was known for its effective management system. Besides the capital, Chung-Hung Motors also brought an effective management system to Wu’s company (Public TV, 2004).

Even if an entrepreneur has failed in a business start-up, he or she may find their courage and confidence in developing a new business plan bolstered by a large pool of potential resources to use. Creating and maintaining relationships with organizations that might supply such resources is a critical manoeuver for an entrepreneur. In the past close proximity was more important in maintaining relationships with stakeholders than it is currently (Nijkamp, 2003).

Relationship With Governmental or Nonprofit Organizations (+)

In many nations, it is helpful for an entrepreneurship to establish good relationships with government units that it must work with. Though, in an epoch of deregulation, this is less important than in the past (Henisz & Zelner, 2005).

Lee successfully got his tea to be the official souvenir of Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in 1997, and he also established relationships with top officials. After 4 years, Lee aggressively used his official relationships to promote Ten-Zen tea to be the souvenir again at the APEC meeting. This cost Lee a million, but the commercial benefit for him was certainly more than that (Tsai, 2002).

Norm for Entrepreneurial Activities (+/-)

The framing force for social action does not necessarily stem solely from social aspects, institutional aspects may also have a part to play. Many studies, when dealing with the issue of collectivity, do not neglect the importance of collective norms for supporting collective action (e.g., Coleman, 1988, 1990; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). The norms of doing business in a specific industry or market can also be seen as the conventions or the “rules of the game.” Although, as discussed above, on occasion entrepreneurial opportunities are associated with creating a higher level of competition through product upgrading, and so on, the norm for entrepreneurs is more focused on surviving competition rather than becoming the top firm.

After having failed at a venture, entrepreneurs mulling over starting a new venture will consider the difficulties that might entail. If they see it as being complex to start-up a particular business, their enthusiasm for it might flag.

Conversely, it might seem generally readily doable. Even when a start-up might seem difficult, the lure of an attractive expected payoff might bring an entrepreneur to start a new business. This illustrative story says much the same:

In the case of the idea of building a new healthcare vehicle, though there were impediments such as the need to pass safety tests, the product was seen as ultimately a potential boon to the firm.

Concluding Remarks And Research Directions

This research-paper discussed entrepreneurial resilience after previous failed ventures.

Successful businessmen and businesswomen are often endowed with vibrant lives and rich business experiences; some degree of failure along the way is not a surprise. In such situations, failure can be seen as valuable, as an intangible asset, for entrepreneurs’ ongoing careers. If they learn from their failures (Shepherd, 2003), internalize the experiences, and raise their heads toward a promising future using proper resilience strategies and actions, entrepreneurial failure can hardly be seen as a liability.

Beyond the social, knowledge, or institutional bases for resilience proposed in this research-paper, specific resilience strategies that can transform resilience motives into practice are imperative. Post failure, entrepreneurs are encouraged to reflect on their strategic resources and capabilities in addition to their emotional reactions. Identifying social capital and knowledge is a starting point because each benefits firm value creation and competitive advantage (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998; Spender, 1996; Grant, 1996). Moreover, discovering the mechanisms by which social and knowledge resources and capabilities evolve into concrete payoffs can be important. For example, trust or trustworthiness (Hardin 2002) may be an important transforming mechanism for all sorts of social relations maintained by entrepreneurs.

The most realistic and important assets for an entrepreneur may be their motives for and capability of resilience— the desire and ability to bounce back from failure, to turn a bad situation into a good one, and to profit from mistakes. While crisis is a challenging test for an entrepreneur’s career, resilience is vital for continuous business operation, innovation, and success. According to these exploratory findings, building effective social relations and reliable knowledge sources may be the most critical imperative for noteworthy entrepreneurship. Moreover, research may extend to discovering how these two sources of advantage interact (e.g., Yli-Renko et al., 2001) to influence resilience or other entrepreneurial consequences.

Aside from exploring the antecedents as research variables pertaining to an entrepreneur’s personal resilience in business, there are several other issues which deserve further research. First, the essence of entrepreneurial resilience should be discussed in depth. Although in this paper we have discussed the “what” of this construct, we simply offered conceptual definitions while foregoing the possibility of deeming resilience as a multidimensional construct (Law, Wong, & Mobley, 1998). For instance, the concept of entrepreneur resilience could, as is commonly seen in the social sciences, be split into the motive and capacity portions. That is, we may distinguish between those who intend to come back after failure and those who may not actually be able to do so. Moreover, an operationalization effort should be conducted to allow for larger scale examinations.

Second, context-specific entrepreneurial resilience theories and practice techniques should be explored. If we agree that complexity is a basic foundation for modern business, the need for various kinds of models to explain resilience for entrepreneurs operating in different businesses, cultures, or institutional environments becomes evident. If we consider technological entrepreneurs (e.g., Astebro, 2004) and social entrepreneurs (Mair & Marti, 2006), for example, we see that they run their businesses in drastically different operating systems, and therefore should have different portfolios of factors affecting their resilience.

Third, the consequences of resilience may prove to be an interesting issue. The word “resilience” typically implies positive measurable performance (e.g., economic returns or profit). However, in management research consequences are oftentimes related to positive and negative outcomes or performance. Psychological results such as satisfaction and fulfilling personal philosophy may play roles. Further, competence results such as opportunity recognition or alertness (Baron, 2006; Kirzner, 1979, 1999; Gaglio & Katz, 2001), or the ability to dominate some industrial standard, as well as changes in strategic directions (e.g., to form an alliance or not; going forward with a public offering or not, etc.), are additional directions for possible future research.

References:

- Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 1—10.

- Aldrich, H. E. (1999). Organizations evolving. London: Sage.

- Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In B. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organisational behavior (Vol. 10). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Amabile, T. M, Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad-emy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154—1184

- APA (n.d.) The road to resilience. Retrieved December 27, 2006, from http://www.apa.com

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Astebro, T. (2004). Key success factors for technological entrepreneurs’ R&D projects. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 51(3), 314-321

- Bandura A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co.

- Barker C. B. (2007). Resilience at work: Professional identity as a source of strength. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan.

- Baron, R. A. (2006). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “connect the dots” to identify new business opportunities. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 104-119.

- Barrett, F. (2004). Coaching for resilience. Organization Development Journal, 22(1), 93-96.

- Bates, T. (1985). Entrepreneur human capital endowments and minority business viability. Journal of Human Resources, 20, 540-554.

- Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72, 551-559.

- Baum, J. A. C., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B. S. (2000). Don’t go it alone: Alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 267-294.

- Bednarzik, R. W. (2000). The role of entrepreneurship in U.S. and European job growth. Monthly Labor Review, 123(7), 3-16.

- Benard, B. (1996). Environmental strategies for tapping resilience checklist. Berkeley, CA: Resiliency Associates.

- Bennis, W. G. (n.d.). Warren G. Bennis quotes. Retrieved January 4, 2007, from http://thinkexist.com/quotes/warren_g._bennis

- Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 107-117.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?” American Psychologist, 59,20-28.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 135-138.

- Brockhaus, R. H. (1980). Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509-520.

- Brooks, R., & Goldstein, S. (2003). The power of resilience. New York: Reed Business Information.

- Cameron, K., Dutton, J. E., & Quinn, R. E. (Eds.). (2003). Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Cameron, K., & Lavine, M. (2006). Making the impossible possible: Leading extraordinary performance—The rocky flats story. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Campbell, D. T. (1960). Blind variation and selective retention in creative thoughts as in other knowledge processes. Psycho-logical Review, 67, 380-W0.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(Suppl.), 95-120.

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 46-55.

- Cunningham, J. B., & Lischeron, J. (1991). Defining entrepreneur-ship. Journal of Small Business Management, 29(1), 45-61.

- Diekmann, A., & Lindenberg, S. (2001). Sociological aspects of cooperation. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social sciences (Vol. 4, pp. 2751-2756). Oxford, UK: Pergamon-Elsevier.

- Drucker, P. (1985). Entrepreneurship and innovation: Practice and principles. New York: Harper & Row.

- Drucker, P. (1993). Post-capitalist society. New York: HarperCollins.

- Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive ad-vantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660-679.

- Ellingson, J. E., Smith, D. E., & Sackett, P. R. (2001). Investigating the influence of social desirability on personality factor structure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 122-133.

- Elliot, A. J., & Dweck, C. S. (2005). Handbook of competence and motivation. New York: Guilford Press.

- Envick, B. R. (2004). Beyond human and social capital: The importance of positive psychological capital for entrepreneurial success. Proceedings of the Academy of Entrepreneurship, 10(2), 13-17.

- Erikson, T. (2002). Goal-setting and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 3(1), 183-189.

- Fligstein, N. (1990). The transformation of corporate control. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fligstein, N. (1997). Social skill and institutional theory. American Behavioral Scientist, 40, 397-405

- Gaglio, C. M., & Katz, J. A. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16, 309-331.

- Garmezy, N. (1991). Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. American Behavioral Sciences, 34, 416-430.

- Goldsmith, A. H., Veum, J. R., & Darity, W. (1997, October). The impact of psychological and human capital on wages. Economic Inquiry, 815-828.

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109-122.

- Gulati, R., Nohria, N., & A. Zaheer (2000). Strategic networks. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 203-215.

- Hamel, G., & Valikangas, L. (2003). The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, 81(9), 52-63.

- Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hayton, J. C. (2004). Strategic human capital management in SMEs: An empirical study of entrepreneurial performance. Human Resource Management, 42(4), 375-391.

- Henisz, W. J., & Zelner, B. A. (2005). Legitimacy, interest group pressures, and change in emergent institutions: The case of foreign investors and host country governments. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 361-382.

- Higashide, H., & Birley, S. (2002). The consequences of conflict between the venture capitalist and the entrepreneurial team in the United Kingdom from the perspective of the venture capitalist. Journal of Business Venturing, 17, 59-81.

- Holaday, M., & McPhearson, R. W. (1997). Resilience and severe burns. Journal of Counseling Development, 75(5), 346-356.

- Holt, D. H. (1992). Entrepreneurship: New venture creation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Hung, S.-C. (2002). Mobilising networks to achieve strategic difference. Long Range Planning, 35(6), 591-613.

- Jn, G. I. (2000). Funny A-Kuei. Business Weekly, 659, 75-76.

- Kets de Vries, Manfred F. R. (1985). The dark side of entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 63(6), 160-167.

- Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, opportunity, and profit: Studies in the theory of entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kirzner, I. M. (1999). Creativity and/or alertness: A reconsideration of the Schumpeterian entrepreneur. The Review of Austrian Economics, 11, 5-17.

- Krueger, N. F. Jr., & Brazeal, D. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91-104.

- Lagerstrom, K., & Andersson, M. (2003) Creating and sharing knowledge within a transnational team-the development of a global business system, Journal of World Business, 38(2),84-95

- Larson, A., & Starr, J. (1993). A network model of organization formation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 17(2), 5-15.

- Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638-658.

- Law, Kenneth S., Wong, C.-S., & Mobley, W. M. (1998). Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 741-755.

- Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G. R., & R, Lester, P. B. (2006). Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Human Re-source Development Review, 5(1), 25-44.

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41, 36-44

- Mallak, L. (1998). Putting organizational resilience to work. Industrial Management, 40(6), 8-13.

- Nijkamp, P. (2003). Entrepreneurship in a modern network economy. Regional Studies, 37(4), 395-405.

- McMillen, J. C., & Fisher, R. (1998). The perceived benefits scales: Measuring perceived positive life changes after negative events. Social Work Research, 22, 173-187.

- McMillen, J. C., Smith, E. M., & Fisher, R. H. (1997). Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 733-739.

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266.

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37.

- Ostgaard, T. A., & Birley, S. (1996). New venture growth and personal networks. Journal of Business Research, 36, 37-50.

- Penrose, E. G. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley.

- Peterson, S. J., & Luthans, F. (2003). The positive impact and development of hopeful leaders. Leadership & Organizational Development Journal, 24, 26-31.

- Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 399-424.

- Public TV (2004). The interview for influential people [Television broadcast]. Taipei, Taiwan.

- Rak, C. F., & Patterson, L. E. (1996). Promoting resilience in at-risk children. Journal of Counseling and Development, 74, 368-373.

- Reagans, R., & Zuckerman, E. W. (2001). Networks, diversity, and productivity: The social capital of corporate R&D teams. Organization Science, 12(4), 502-517.

- Reinmoeller, P., & van Baardwijk. N. (2005). The link between diversity and resilience. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46(4), 61-65.

- Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(31), 307-321.

- Rutter, M. (1993). Resilience: Some conceptual considerations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14, 353-367.

- Ryans, C. C. (1997). Resources: Writing a business plan. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(2), 95-98.

- Sagor, R. (1996). Building resiliency in students. Educational Leadership, 54(1), 38-41.

- Sheffi, Y., & Rice Jr., J. B. (2005). A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(1), 41-48.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (2000). Entrepreneurship as innovation. In R. Swedberg (Ed.), Entrepreneurship: The social science view (pp. 51-75). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Shapero, A. (1981). Self-renewing economies. Economic Development Commentary, 5, 19-22.

- Shepherd, D. A. (2003). Learning from business failure: Proposition of grief recovery for the self-employed. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 318-328.

- Smokowski, P. R., Reynolds, A. J., & Bezruczko, N. (1999).

- Resilience and protective factors in adolescence: An autobiographical perspective from disadvantaged youth. Journal of School Psychology, 37, 425-448.

- Spender, J.-C. (1996). Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(Special issue), 45-62.

- Starr, J. A., & MacMillan, I. A. (1990). Resource cooptation via-social contracting: Resource acquisition strategies for new ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 79-92

- Stein, M. I. (1991). Creativity is people. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 12(6), 4-11.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2003). WICS: A model of leadership in organizations. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2(4), 386-401.

- Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1995). Defying the crowd: Cultivating creativity in a culture of conformity. New York: Free Press.

- Sullivan, R. (2000). Entrepreneurial learning and mentoring. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 6(3), 160-175.

- Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 27-43.

- Tang, C. (2004) Happy boss, media interview. Retrieved December 12, 2004, from http://www.careernet.org.tw/openhtml. php?title=close&html=html/happyboss_1.htm

- Tsai, F. S. (2005). Composite diversity, social capital, and group knowledge sharing: A case narration. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 3(4), 218-228.

- Tsai, H. C. (2002). Lee’s retrospection—How Ten Ren failed and Ten Fu success in China. Taipei, Taiwan: Common Wealth Publication.

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320-333.

- van Gelderen, M., Thurik, R., & Bosma, N. (2006). Success and risk factors in the pre-startup phase. Small Business Economics, 24(4), 365-380.

- Oxford Dictionary (online version). Resilient. Retrieved August 4, 2007, from http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/ orexxsilient?view=uk

- Wilson, S. M., & Ferch, S. R. (2005). Enhancing resilience in the workplace through the practice of caring relationships, Organization Development Journal, 23(4), 45-60.

- Yang L. G. (2002). I will success. Business Weekly, 756, 57-58.

- Yang, G. K. (2002). From one unemployed to a hero. Taipei, Taiwan: Po-Pin Publishing Co.

- Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yli-Renko, H., Autio, E., & Sapienza, H. J. (2QQ1). Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(б-7), 587-61З.

- Zahra, S. A., Kuratko, D. F., & Jennings, D. F. (1999). Entrepreneur-ship and the acquisition of dynamic organizational capabilities. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 24(1), 5-1Q.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.