This sample Flexible Labor Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

This research-paper deals with one of the most discussed topics among contemporary management practitioners and scholars: flexible labor. We present an integrated framework and discuss numerical flexibility (i.e., work time and nonpermanent employment relationships) as well as functional flexibility (i.e., external and internal employ-ability) and their interrelationships. In this context, drivers and consequences of flexible labor play an important role for both firms and workers. The research-paper begins with an outline of prominent theoretical frameworks of flexible labor. Next, the different forms of flexible labor will be presented in detail. This research-paper not only offers an overview of relevant academic literature from different disciplines (e.g., labor economics, labor law, human resource management [HRM], psychology, and sociology) but, given the global relevance of the flexibilization of labor, we have also made a point of giving it a strong international character.

Introducing Flexible Labor: Firm Demands And Worker Needs

The technological changes in processes and products, the shortening of product life cycles, the increase in competition under price pressure, and the intensified international competition have changed the preconditions for organizational vitality since the 1970s. According to Bolwijn and Kumpe (1990), survival nowadays can be ensured by a combination of price, quality, flexibility, and innovation. In this research-paper, the focus is on one such market requirement: flexibility. Flexibility is seen here as a precondition for the other mentioned pillars of organizational success. As a managerial task, flexibility involves the creation or promotion of capabilities for dealing with situations of unexpected disturbance. Companies can enhance firm maneuverability with different strategies: flexibility in procedures, in volume and mix of products, in speed, in technology, in organization structure, and in culture (Volberda, 1996). Here we focus on flexibility in the form of moveable human resources. In order to deal with all other areas of flexibility adequately, employees have to adapt to changes appropriately and quickly. Based on Blyton and Morris (1992, p. 116) and Atkinson (1985, p. 3), the following definition of flexible labor can be formulated: the ability of management to vary the use of the factor labor in a company according to fluctuations and changes in production activity and according to the nature of that activity itself.

At least in Western Europe, monetary yields as well as working time, labor contract, and health and safety at work are strongly anchored in labor law and collective agreements between employer and employee representatives. Thus, organizations’ demands for flexible labor are restricted by external, institutionalized forces (see Looise, van Riemsdijk, & de Lange, 1998). For this reason, when the different forms of flexible labor are elaborated on here in detail, the relevant regulations associated with them will be highlighted. But before proceeding to the detailed presentation of the different forms of flexible labor, an outline of these forms will be presented in the following paragraph.

A Framework for Flexible Labor

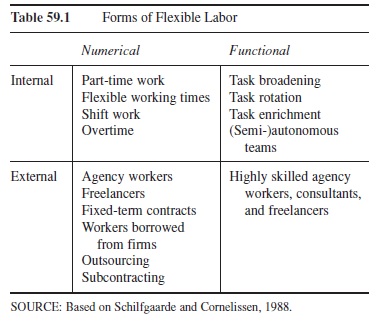

Schilfgaarde and Cornelissen (1988) presented a framework that encompasses different forms of flexible labor. The authors differentiated between two dimensions of flexible labor: (a) numerical versus functional and (b) internal versus external. The first dimension deals with the difference between the adaptability of the production activity (numerical flexibility) and the adaptability of the nature of that activity (functional flexibility). The second dimension concerns the use of employees for realizing numerical and/or functional flexibility. Employers can enhance the flexibility of their staff (internal labor market), can hire employees temporarily, or can subcontract and outsource labor (external labor market). Thus, four forms of flexible labor can be distinguished, and within each form, different instruments do exist.

From the firm perspective, numerical flexibility is usually seen as a strategy to reduce labor costs; functional flexibility is usually linked to an increase in quality and innovation. However, from the perspective of the workers, flexible working times as well as employability (internal functional flexibility) are often seen as beneficial. With respect to the former, firms help workers realize work-life balance. Thus, firm demands and worker needs seem to meet in both forms of internal flexibility. In contrast to this, many authors seem to believe that external numerical flexibility is favorable only for firms, as if nonpermanent employment relationships, particularly those involving workers who are not considered high professionals, are based purely on organizational demands. In this research-paper, both of these and other rather extreme viewpoints will be put into perspective.

Table 59.1 Forms of Flexible Labor

Table 59.1 Forms of Flexible Labor

The most influential model describing firm strategies for managing flexible labor is the dualistic model of the flexible firm proposed by Atkinson (1984, 1985). His core-periphery model has been the subject of much research and debate. According to the author, firms try to establish a relatively small core of full-time employees with job security who conduct the organizations’ key activities and have high levels of functional flexibility, good development and career opportunities, and excellent monetary benefits. At the same time, organizations externalize a thick layer of non-core activities or persons, also called peripheral activities and workers. Noncore workers receive only a temporary commitment from the firm—that is, temporary contracts or agency work. They receive less attractive material and immaterial benefits from the user firm—that is, few or no opportunities for challenging tasks, reduced internal mobility, and limited (fringe) benefits. Thus, organizations can adopt a mixed strategy, trying to obtain all forms of flexibility simultaneously. It is also assumed that the periphery protects the core from fluctuations and changes in numerical production activity. The commitment necessary for working beyond contract can and will be developed and is exclusively expected from only the core workers. Those who have a permanent position in the firm receive all of the HRM conditions known to be drivers of commitment and these workers consequently exhibit behavior that contributes to organizational well-being. However, Dutch research has shown that external flexibility does not exclude functional flexibility within the firm. The firms established long-term relationships with good agency workers: Many of the agency workers had worked for the companies for years, being hired repeatedly in peak periods. After the initial period (6 months), agency workers conducted the same firm-specific activities and received equal opportunities for task rotation, task enrichment, and (paid) education and training as their core colleagues with a regular contract (Torka, 2004). In the next sections, different forms of labor flexibility will be discussed in detail—bearing in mind that they are less “worlds apart” than at first may be suggested.

Internal Numerical Flexibility: Working Time

Without changing the workforce size, firms can adjust the volume of hours worked in a company simply by letting incumbent workers work more or fewer hours than the standard (agreed upon) amount. Overtime work is probably the best known and oldest example of an internal numerical flexibility tool. Temporary working-time reduction is another. When working-time reduction becomes a permanent, structural feature of a job or employment relationship, it takes the shape of part-time work. In this section, however, we will focus on measures that temporarily adjust the number of hours worked in a firm.

Why Internal Numerical Flexibility: A Firm and Worker Perspective

Working-time flexibility is a common flexibility tool for many firms in several northwest European countries.

Employers rely on this type of internal flexibility because external flexibility options are limited, either by law (high levels of employment protection) or through self-regulation (substantial terms of notice in collective agreements). An industry where working-time flexibility is particularly dominant is the logistics industry. High levels of flexibility, which are sometimes hard to predict, characterize this industry. Instead of adjusting the size of the workforce to changing market demands, logistics companies can opt to vary the volume of working hours. Incumbent employees work longer hours during peak periods and take time off when business is slow. Examples from Danish firms show that extra hours worked are stored in a virtual hours account. Rather than receive monetary compensation for the overtime work, employees can draw time from these accounts. Typically, these hours can be spent as paid leave during periods of low customer demand. Ideally, the periods when workers want to take time off (e.g., for vacation, education, care of dependents) coincide with the slow business spells. In the Danish examples, employees negotiate with line managers and/or HR staff in order to coordinate their preferences with the company staffing needs (Van Velzen, in press). Negotiations take place within the boundaries set by the collective agreement. Average weekly hours are consolidated for a longer period, sometimes up to one year. This annualization provides companies with the possibility to redistribute available working hours over peak and slow periods. This practice is taken one step further in several Swedish organizations (e.g., hospitals, apparel manufacturing, consumer electronics), where software-supported “self-rostering” enables employees to realize a work-life balance, while at the same time providing the company with working-time flexibility.

It is important to realize that, particularly since the beginning of the 21st century, much of the working-time flexibility in European countries has been regulated through legislation (e.g., Austria and France), collective agreements (e.g., Danish banking industry and German printing industry), and company agreements (e.g., Belgium and the Netherlands). In some countries, working-time flexibility has been initiated by firms, often in return for job-security guarantees (e.g., in several high-profile firms in Germany). Increasingly, working-time flexibility also serves worker purposes, notably in cases where workers want to better combine work and private duties, the so-called work-life balance, for instance in Austria (Thornthwaite & Sheldon, 2004). These European initiatives should be seen in light of the Employment Guidelines, which were drafted by the European Commission. Since the late 1990s, these annual guidelines have called for a modernization of work including flexible working arrangements in which company productivity and competitiveness is improved, yet a balance between flexibility and security is simultaneously facilitated. Working-time flexibility is seen by the European Commission as a potential tool for realizing such a balance. Thus, while at the micro level, companies and workers are coming up with ideas, preferences, and desires to make working time more flexible, a supranational coordination mechanism supporting an integrative approach of working-time flexibility is becoming more and more visible as well.

Internal Numerical Flexibility: consequences for Firms and Workers

Let us stay with the widespread use of various working-time flexibility scenarios in Europe. When faced with the economic shocks in the 1970s and 1980s, European employers did not lay off workers but, instead, pressured by the unions, introduced working-time reduction schemes and work sharing (e.g., France, Germany, and the Netherlands). Then, according to Alesina, Glaeser, and Sacerdote (2005), a “social multiplier” may have triggered a further reduction of working hours economy wide. They conclude that this social phenomenon has resulted in Europeans deliberately working fewer hours than their American and Japanese counterparts would. Furthermore, the European workers appear to be very happy with this state of affairs. This may possibly be reflecting an awareness among European workers, for instance, that issues such as time squeeze and work-life balance need to be addressed much more so than the pursuit of material wealth.

This may help explain the willingness of workers to accept more flexibility, but only if work-life preferences can be realized through such a strategy. The realization of these preferences partly depends on the bargaining position of workers (and is thus dependent on the labor market situation), but also on the HRM of individual firms.

The outcome of so-called Damocles bargaining (take it or leave it) is a flexibility strategy that only serves the company’s need. Worker preferences are not taken into account. Working-time flexibility provides an opportunity for companies to not only retain, but also motivate incumbent workers. The tendency of many firms in Europe to explore the possibilities of this type of numerical flexibility suggests that companies are not only increasingly aware that corporate social responsibility start in the own firm. It also hints at a corporate sensibility, given the demographic fact that skilled and motivated workers will be harder to find in Europe.

Internal Functional Flexibility: Employability Within The Firm

In this section, we deal with internal functional flexibility, defined as the flexibility that one can assume is directly linked to the workers task content and development opportunities, as well as to organizations’ decisiveness to respond accurately to changes related to quality issues. Functional flexibility is strongly linked to internal labor markets: getting the job done with the same staff, even when products and production changes. Changing organizational demands requires internal employability from employees, which can be linked to horizontal (a different but not more difficult job) and vertical (a different and more complex job) mobility at the current employer. When aiming for task broadening, different tasks with the same degree of complexity get integrated: Workers have to carry out more tasks. Task rotation concerns the exchange of tasks between workers, but the level of difficulty remains the same. Contrary to both mentioned forms of functional flexibility, task enrichment includes the qualitative improvement of work: Workers not only perform executive tasks, but they also get responsibilities for preparation, control, and so on. While broadening, rotation, and enrichment refer to task restructuring on the level of an individual employee, (semi-)autonomous teams refer to changes in the quality of work for groups of workers: As a group, they become responsible for a part of the production process. The group is supposed to lead itself, although the supervisors stay responsible.

Why Internal Functional Flexibility: A Firm and Worker Perspective

To increase cost effectiveness, many Western companies have outsourced their noncore activities to low-wage countries, but competing in terms of price is not enough nowadays to take part in the fierce international contest. Technological and market developments have often forced organizations to meet higher requirements such as quality and innovativeness. Both requirements are interwoven with knowledge intensification, and as a result, firms have to invest in their human capital in order to guarantee optimal adaptability to these types of demands. While the need for semiskilled and unskilled workers is decreasing, qualifications required for new and existing jobs become higher. This new deal is well known as employability: Workers are expected to adapt easily to the changing upgraded demands. Functional flexibility is assumed to have a positive relationship to the quality of work. It is important to note that some authors argue that the link between an increased quality of work and quality and innovation improvement is an indirect one: It is believed that challenging, complex, and integrated tasks lead to enhanced attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction and commitment) and, thereby, to employee behavior that contributes to firm improvement.

A changing labor market is a second factor that favors an internal functional solution. The current and future labor market situation makes internal functional flexibility increasingly inevitable. Although the labor market is still quite extensive in many countries, certain industries and companies (already) suffer from a lack of qualified employees. Due to the aging Western society and the change in employee preferences, the lack of qualified staff will continue to grow. Because of this, not only do Australia, the United States, and New Zealand have Green Card policies for attracting immigrants with highly desired, rare qualifications and skills, but Western European countries do as well. In Germany, for example, although the unemployment rate approached 10% in January 2007, there is a clear lack of skilled workers. According to the Cologne Institute for Business Research, about 20,000 jobs that require highly skilled workers are not filled because of a shortage of skilled labor. The problem is particularly evident in health care, corporate management, engineering (especially the IT sector), and other technical occupations. Social partners (employers and unions) and government aim for solutions outside of firms (e.g., revising and softening immigration laws and raising the retirement age) as well as solutions inside firms. Concerning the latter, it is assumed that companies have to provide not only flexible working times but also further training for the existing labor force. This means that workers have to be prepared for an enhanced internal functional flexibility.

From the perspective of the workers, two arguments for internal functional flexibility can be identified: (a) humanization of work and (b) increased opportunities on the internal and external labor market. Tayloristic work (the splitting of tasks into small pieces of routine and boring work and a sharp division between execution and control), which is accompanied by a “homoeconomicus” portrayal of mankind (the only motivators are financial incentives), can be seen as dehumanizing: Mankind is a (detached) continuation of the machine. Therefore, rebuilding tasks can be characterized as “humanizing.” Furthermore, due to organizational investments into the workers’ capabilities, workers can benefit from their enhanced competences and skills. It will be easier for them to find a job within or outside of the current employer. Concerning the latter, a firm takes risks when it invests in workers usability.

However, according to Boltanski and Chiapello (1999), employment relationships have changed to “cité par pro-jets”—from long-term mutual loyalty relationships to short-term business connections based on projects. They propose that the so-called new deal is lopsided. For the worker, this means that employability in general—and, thus, other forms of flexibility—are not a voluntary choice based on emotional persuasion or identification, but based on necessity. Employees have to adapt.

Internal Functional Flexibility: consequences for Firms and Workers

In HRM literature, firms offering challenging and complex jobs in combination with a continuous improvement of workers’ competences are often labeled as high-commitment or high-performance work organizations. This means that, if management invests into workers, organizational prosperity will be a direct and logical consequence. However, the contribution of functional flexibility to quality and innovation is not self-evident, making the how question a central one. Not all forms of functional flexibility can be linked to workers’ and firms’ enlightenment. Herzberg (1968) argued vehemently against task broadening and rotation. According to Herzberg, both interventions have nothing to do with a qualitative enhancement of the quality of work, but only with an increase in the volume of work for the worker. As a consequence, such changes will not contribute to motivation and commitment but to more work-related pressure and stress. According to him, only better jobs (enrichment) will lead to outcomes desired by firms and workers. Research by Goudswaard, Kraan, and Dhondt (2000) supports Herzberg’s assumption. For workers who rotate over tasks on a regular basis or who experience a broadening of tasks, task demands are higher and autonomy is lower, and as a consequence, the risk of being subject to work pressure is higher than it is for workers without these regular switches. Workers who take over supervisor tasks (task enrichment) experience higher risks of emotional exhaustion, although this can be partly absorbed by the increase in autonomy and the opportunity to learn. However, not all human beings are looking for occupational advance. People do differ and have individualized needs when referring to occupational advancement. Taking all of the aforementioned into account, successful functional flexibility depends greatly on management’s ability to identify individual worker needs. In other words, obliged task improvement can result in contraproductive employee behaviors and unforeseen, negative company results.

External Numerical Flexibility

IBM has halved its number of direct employees from 440,000 to 225,000 worldwide but we still have the same overall number of jobs as before, around 500,000. We have just shifted their status. The group will never go back to full employment in any way. It got its fingers too badly burned in the 1980s. (Peter Hagger, as cited in K. Purcell & J. Purcell, 1998)

Statistical evidence on a larger scale supports the changes in employment relationships reflected in this comment. Employment through temp work agencies (TWA), self-employment, and fixed-term contracts seems to have experienced a steady growth in almost all European countries, the United States, and Australia. Over the past 15 years, temp agency work has at least doubled in nearly all European countries (Storrie, 2002). In contrast to European countries, there are no regulations in the United States for the agency industry at the federal level. Despite this fact, the Netherlands has one of the highest percentages of agency workers in the world (2.6%), surpassed only in the United Kingdom (5%). In absolute size, the largest staffing market is that of the U.S. economy (43%). Olsen and Kalleberg (2004) concluded that Norwegian firms make greater use of nonstandard arrangements than U.S. firms. They name the following two reasons, both of which apply to other European countries as well: the more restrictive regulations on dismissal and the generous access to leaves of absence.

In this section, all employment relationships that are different from a permanent, regular one are named nonpermanent or atypical. Temping relationships refer to contractual triangles—a ménage à trois—between one employee, one employer, and a client organization such as a temp agency work, personnel on loan, or labor pools. While fixed-term employees and freelancers are temporarily on the company payroll, workers under a temping relationship have an employment contract with a temp agency or con-tract company and are hired out via a commercial contract to perform work assignments at the user firm. Most research has been done among agency workers. Knowledge about other temping relationships is very limited.

Atypical employment relationships include highly skilled (e.g., consultants) as well as low-skilled (e.g., manufacturing) workers. However, highly skilled but fixed-term labor is not hired because of fluctuations in standard (production) demands but because of fluctuations of a nonstandard nature: These workers possess certain knowledge and/or skills that are not available and needed typically and permanently within the company, but only for a certain period. Their so-called external functional flexibility will be discussed in the next paragraph. In this paragraph, the central focus is on the average, low- to medium-skilled, nonpermanent worker. After discussing insourcing (the use of agency staff) and other forms of atypical employment relationships in detail, we go into the other management strategies of external numerical flexibility: outsourcing, subcontracting, and offshoring.

Why External Numerical Flexibility: A Firm and Worker Perspective

So why do companies seem to hire more atypical workers than in the past? The number one argument is clear: reducing (labor) cost risks under uncertainty. Atypical workers are not necessarily cheaper than one’s staff is, but in the case of agency workers or freelancers, client organizations have to pay only for worked hours or fulfilled assignments. For many firms, the amount of workers needed differs over the year and sometimes within a month or even a week (peak and dale periods). Nonpermanent workers can also replace sick, pregnant, or on holiday permanent staff. However, the question of replace ability depends strongly on the nature of the job. For example, finding a temporary stand-in for a secretary, assembly worker, or someone with more generalist knowledge and skills will be easier than replacing an employee with rather rare and/or firm-specific competences. Both reasons, cost effectiveness and temporary replacement, can be characterized as defensive or reactive. Two proactive or strategic motives for nonpermanent and agency work in particular can be identified: (a) as buffer for the own, regular personnel and (b) as a trial period for intended permanent staff. Concerning the latter, in Europe, dismissal is more difficult than in the United States due to stricter regulation. Furthermore, when offering a permanent or fixed-term contract, the probation period is also shorter. In the Netherlands, the maximum probation period is 2 months. Only within this period can employer or employee terminate the contract without any consequences. However, after this period, dismissal is more difficult due to regulated terms of notice and, at least for the Dutch situation, the involvement of the labor court. According to Berkhout and Van Leeuwen (2004), the three main firm motives for atypical work and especially agency work are flexibility, costs, and screening.

Berkhout and Van Leeuwen (2004) went on to describe the three worker motives as employability, harmonization, and screening. Employability refers to the gaining of work experience and the relative ease of finding a nonpermanent job. For younger and unemployed workers, temporary work can act as a kind of stepping-stone toward permanent employment (e.g., Finegold, Levenson, & Van Buren, 2003).

Harmonization deals with the supple combination of different life spheres. For example, harmonization between employment and education (many agency workers are quite young), employment and family life, employment and leisure interests. The harmonization motive is strongly connected to the agency work flexible working hour’s relationship: Temporary contracts are more common among part-time than among full-time workers.

Through screening, employees get a chance to work for different employers and therefore can choose the best. This motive may be better realized under tight labor market conditions than during economic recessions. Employees can also suspend important lifetime choices through contingent work.

External Numerical Flexibility: consequences for Firms and Workers

In the literature, the disadvantages of atypical employment for the knowledge society and for firms are placed in the foreground. It is stressed that the cost savings resulting from agency work or other forms of external numerical flexibility may be beneficial for companies, but only in the short term. In the long term, when aiming for strategic targets such as quality and innovation, hire and fire practices will be disastrous. A substantial number of HRM scholars are convinced that decreased opportunities for lifetime employment change the employment relationship and, more specifically, change the underlying psychological contract concerning demand and supply. It is assumed that the expectations between employers and employees transfer from a relational (long term) into a transactional (short term) psychological contract based on monetary exchange. As a consequence, worker attitudes will change from being commitment driven to being economically driven (e.g., Rousseau, 1995). Since it is assumed that a committed workforce is necessary for stimulating and grasping quality, as well as enhancing innovativeness, some scholars, not surprisingly, are convinced that nonpermanent work cannot be advantageous for firm effectiveness in the long term.

Nonpermanent work seems to have many negative consequences for employees as well. For example, much research shows that agency workers have less attractive HRM conditions (e.g., contract security, salary, and job characteristics) than employees with a permanent contract do. On a more general level, Letourneux (1998) concluded that the labor conditions of nonpermanent workers are worse than those of employees with a permanent contract are. He argued that it is more physically demanding work involving repetitive tasks, nuisance work, monotonous work, and fewer opportunities for developing skills. In a Dutch/United States comparison for the IT and building industries, Van Velzen (2004) showed the many challenges and few possibilities for flexible workers to receive training that keeps them employable. All of the previously mentioned conditions are sources or antecedents of job satisfaction and commitment. Therefore, the assumed relationship between contingent work, employee attitudes, employee well-being, and organizational effectiveness seems logical. But is it also true?

External Numerical Flexibility: challenging common sense and Research Findings

Little research challenges the previously mentioned relationship, but some of the few provocative results will be presented here. To begin with, a challenge to the nonpermanent work/bad job link can be found in the research conducted by Saloniemi, Virtanen, and Vahtera (2004, p. 203), which showed that fixed-term employment does not indicate social exclusion, low-job control, nor high-job demands. Moreover, exposure to high strain was more common among permanent than among nonpermanent employees. Casey and Alach (2004) reported reasons mentioned by agency workers as to why agency work is not inevitably worse than permanent employment:

Many report that they choose to temp as an escape from the “stresses and abuses,” and the “politics” often experienced in permanent employment roles in organizational workplaces. Some reported their wish to avoid the responsibilities and commitments and management practices incumbent in permanent positions. Others reported their wish to alleviate the boredom of routine clerical jobs and their disaffection with conventional jobs by opting for variety and discontinuity with different employing organizations. (p. 468)

Thus, the previously mentioned positive effects of agency work can be understood as triggers for voluntary nonpermanent work (for more reasons, see Torka & Schyns, 2007). With this in mind, external numerical flexibility can also be seen as meeting both employer demands and employee needs. Torka (2004) found that even nonpermanent workers who would have preferred a permanent relationship (i.e., involuntary temp work) can develop feelings of commitment toward the user firm. This largely depends on the organization’s treatment of temp workers. She advised organizations to minimize differences between permanent and nonpermanent staff on the whole range of HRM practices (e.g., rewards, development opportunities, employee involvement, and work system), thus adopting equal treatment policies and practices.

Outsourcing, Subcontracting, And Offshoring

The ability to breakdown entire business processes into small components, leading to a strong division of labor, has enabled firms to pick and choose the physical location and the type of worker needed for each part of a firm’s operations. The emergence of the global economy not only has led to a growth in the number of markets for products and services and the entry of worldwide competition. It has also created more possibilities for moving work and workers across the globe. Multinational firms transfer manufacturing processes to low-wage countries in Latin America, southeast Asia, and eastern Europe. Initially, low-skill, manual work was offshored by companies in Western countries to low-wage countries. Offshoring means moving work to low-cost countries. Probably the most striking examples are the plant closings of American automotive companies in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s and the subsequent opening of new car factories by these same companies in Mexico and other Latin American countries. More recent practices of subcontracting (contracting work out to another firm) of manual labor can be found in the consumer electronics industry. Here so-called original equipment manufacturers (OEM) have subcontracted the manufacturing of different components for a single product (e.g., a computer) to firms in low-wage countries such as Taiwan, China, and Korea. According to K. Purcell and J. Purcell (1998), outsourcing means that an outside contractor takes over the in-house function and manages it on the client company premises (p. 50). For example, some temp agencies offer not only temporary labor but also HRM services for companies such as salary administration or the recruitment and selection of permanent staff. However, K. Purcell and J. Purcell stated that much of the growth in outsourcing is taking place inside the company and often involves employees changing their contract of employment but still working with the original employer. While much of the manufacturing and assembly of components are moved abroad, plenty of this work is done in the country of origin of the OEM. Many computer hardware firms in Silicon Valley rely on local manufacturing firms for the production of their components. The employees in these flexible, low-pay manufacturing jobs are often immigrant workers (see Hossfeld, 1995).

Outsourcing and offshoring are not limited to manual, low-skill labor. Countries such as India have seen substantial employment growth in its IT industry due to the decision of many Western technology firms to outsource software programming, as well as research and development (R&D) activities. This development, which is becoming more common among European and North American companies, follows a previous trend: the migration in the 1990s of so-called “knowledge workers” from developing countries to, predominantly though not exclusively, IT (-related) firms in the United States. In other words: the beginning of the 21st century is marked by taking work (and employment) from one (Western) country to another (developing) country, while the Internet boom of the late 1990s was characterized by bringing workers in from one (developing) country to another (Western) country. In the next paragraph, we focus on the external flexibility elite: nonpermanent workers with knowledge and skills rare within and only temporarily desired from the user firm.

External Functional Flexibility

There is a fine line between external numerical flexibility and external functional flexibility, and sometimes the two may well go hand in hand. External functional flexibility addresses a company’s need for a broad variety of skills that are not used very often; external numerical flexibility addresses the issue of sheer volume.

Why External Functional Flexibility: A Firm and Worker Perspective

The growing use of external functional flexibility can be seen as a response to a company’s strategy to reduce its activities to the very core. This often leads to the abandoning of IT, legal, financial, and other more support-type operations. Typically, these high-skill tasks are increasingly carried out by so-called professionals who may move about the labor market as free agents (Pink, 2002) or contractors (Kunda, Barley, & Evans, 2002). The services of these professionals are insourced by firms that, given the move back to core activities, do not want to have these experts permanently on their payroll. However, the employment status of these high-skill professionals varies. They may be employed through an intermediary organization (e.g., a consultancy firm, where they are an employee) and work temporarily at the client firm, or they may choose to work flexibly as a contractor or freelancer, deciding the timing, content, and location of the job for themselves. An individual’s decision to become a contractor may be based on a variety of reasons. Income enhancement under tight labor market conditions is a major incentive for workers to go independent (Kunda et al., 2002). The monetary returns of scarce skills held by highly flexible workers are not limited to white-collar professionals. In her study of four Dutch metal companies, Torka (2004) showed that blue-collar workers (welders and fitters) who work for specialized temp agencies earn more than regular staff do. In general, labor market conditions that favor the position of workers typically contribute to making it attractive for employees to move about the labor market in search of the best wage, most challenging job, and most inspiring workplace. This job-hopping is likely to be dependent on a worker’s personal situation: school graduates and other newcomers on the labor market in early stages of their life may feel attracted to the perspective of obtaining broad experience by working temporarily in different jobs. The key factor for external functional flexibility is the skill specificity, which typically involves workers with more experience who are not necessarily seeking financial security.

External Functional Flexibility: consequences for Firms and Workers

One key feature of flexible specialists is that the skill needed by firms is available on call, assuming that labor market conditions are not tight. This means that firms do not have to invest in the skills and that return on skill investment is not a concern. On the other hand, flexible specialists come at a price: Firms pay substantial fees to freelancers and contractors. This is not surprising, given the fact that these flexible specialists often have to pay for their pension, health care, and social insurances. Another concern is that, in order to keep up with market and product developments, contractors have to pay for their own training. Interestingly, much of the relevant skills of flexible specialists stem directly from the fact that they are flexible: They work at different firms and thus acquire a wide array of experience directly related to their craft. A concern for firms relying on particularly high-skilled contractors such as consultants is that these professionals carry with them the skills and knowledge that they acquire on a particular assignment. As Stone (2002) described, this may lead to a dispute over the ownership of human capital: Does the employee own the knowledge obtained from a firm, or is the employee somehow indebted to the firm that enabled him or her to acquire this knowledge? Should workers be limited in applying the knowledge obtained at one workplace elsewhere? While firms do not risk losing training investments, they do run the risk that trade-sensitive information can be used outside of the home company. While this may hurt individual companies, the free circulation of knowledge can boost the competitiveness of an entire economic region such as Silicon Valley (e.g., Saxenian, 1996). On the other hand, in terms of innovation and knowledge creation, the use of flexible specialists, both high skilled and low skilled, may be beneficial even for individual firms. Matusik and Hill (1998) suggested that, in certain environments, flexible work can contribute to accumulating and creating valuable knowledge. Using data from a survey of U.S. firms, Florida (2002) stated that instable networks rather than tight-knit communities are most innovative. Clearly, a firm should prepare for the fact that the company will become part of the experience of the flexible specialist. Firms that want to use flexible specialists should be willing to share the expertise of these contractors with the outside world, even if this means sharing part of the company with the outside world.

Conclusion

In this research-paper, we presented an overview of one of the most discussed issues in contemporary management: flexible labor. For future managers, an important question has not yet been answered: How can labor flexibility be balanced with other desired outcomes such as quality and innovativeness? This applies in particular to the type of flexibility that has met with the most skepticism: external flexibility and, more specifically, temp agency work. The first part of the following section will be devoted to this subject. In the second part, we will discuss future developments in flexible labor, taking market as well as sociocultural developments into account.

Flexible Champions: Creating Win-Win Situations

How can flexibility be managed in such a way that it really does contribute to organizational success? Firm performance (e.g., financial well-being, improvements in quality and innovation) strongly depends on workers’ competences and their willingness to behave in line with the organization’s strategic goals. Research shows that satisfaction with HRM policies and practices are strong predictors for working “good and fast,” as well as for so-called extrarole behavior, also known as organizational citizenship behavior. Consequently, firms would be wise to meet not only the market requirements but also the workforce requirements. Organizations surely want all workers to give their utmost including temporary staff. As a consequence, firms have to attend to the needs of peripheral workers as well. Moreover, and this is especially true for firms that have to deal with recurring peaks and drops in the business cycle, organizations will want to hire the same competent and reliable temp workers repeatedly, as this will save them the initial prepping periods and the costs related to it. However, the willingness of these temp workers to continue working on an interval basis at the same firm is likely to depend strongly on the treatment they have received in the past.

Companies have to meet the interests of workers, and these interests differ. Not everyone wants to move up the ranks, is looking for challenges in work life, or is looking for continuous improvement of knowledge and skills. Some workers prefer full-time work, while others would like to create a better balance between work-life and private-life interests through working-time flexibility. Many scholars still believe that job security is a universalistic worker need, but this ignores that part of the workforce that has actually chosen to work with changing work locations and footloose contracts in order to breach routine. And not only highly educated professionals seem to appreciate the advantages of a nonpermanent employer. Thus, as preferences differ, among both the regular staff and the buffering workforce, HRM must provide space for each individual by using an “a la carte” approach: The needs of the company and of all its workers have to be mapped and matched as far as possible. Direct supervisors—those who are responsible for operational HRM—play a major role in realizing this.

Back to the Future: Developments in Flexible Labor

Due to changes in sociocultural environments, at least in Western countries, our contemporary knowledge may well be outdated by tomorrow. Due to international, technological, and sociodemographic developments, employer demands and the labor market change. Concerning the former, new competitors have penetrated the global market. The balance of economic power has shifted to the East, leveling the playing field for countries such as China and India. In addition, Western companies have discovered new low-wage countries in central and eastern Europe such as Bulgaria and Romania (European Union members since January 1, 2007). All of these developments may also turn the (flexible) labor markets upside down worldwide. For highly educated professionals with international ambitions and/or within globally operating companies, the world has gotten bigger. Intercultural and language skills different from those important today are gaining importance. In other words, the competences of these professionals need to undergo a continuous upgrading. The increased off-shoring of noncore activities to low-wage countries and rapid technological progress will hit the unskilled and other people with a weak labor market position even harder than it already does today. Millions of jobs will be diminished or emigrated, leaving fewer jobs for the vulnerable in Western societies. However, demographic developments may soften the phenomena associated with the replacement of firm activities.

The changing demography of the labor market is one of the two factors that play a role in determining the type of flexibility applied by firms. The other factor is related to the growing awareness of transaction costs among firms using flexible labor. Given the forecasts regarding the slowing influx of young people into the labor market, firms will increasingly face difficulties attracting and retaining skilled and motivated workers willing to work on a flexible and insecure basis, that is, without the perspective of a permanent contract. This suggests that companies that need to be flexible will have to look for that flexibility, not in the external labor market but rather in the internal labor market. In other words, the flexibility has to be sought and found among the incumbent, core workforce. Following the distinction applied in this research-paper, this means that this flexibility can either be realized by making workers more functionally flexible and/or by making them more numerically flexible. Job rotation, combined with worker training, provides workers with the possibility of enhancing their employability, while at the same offering functional flexibility to the firm. Working-time flexibility has the potential to address both the worker’s need for a work-life balance and a firm’s desire to adjust the volume of working hours inside the company when customer demand fluctuates.

In line with transaction cost theory (Williamson, 1975), firms will benefit from long-term, steady relationships with their employees. Recruiting, screening, selecting, training, and familiarizing workers with the company’s business process involve substantial material and immaterial investments. These investments are higher the more a firm relies on external flexibility, that is, on a recurring influx of new, temporary workers. However, in general, companies should realize that labor flexibility is not an independent goal, but a means to achieve other strategic targets such as cost effectiveness, quality, and innovation. As explained previously, there is no sustainable future for Western companies if they attempt to compete on the basis of wage costs, as foreign competitors with a nearly endless reservoir of cheap labor have entered the market. Therefore, reconsideration on and strengthening of quality and innovative capacity needs to take place, even more so when we consider the aging society. In terms of the issue of labor flexibility, this means that the internal maneuverability of workers will regain importance and the temporary insourcing of labor will lose ground. Rather than simply following Peters’ (1999) strategy, “innovate or die,” we suggest a strategic management style that adds “innovate and flexibilize or die.”

References:

- Alesina, A., Glaeser, E., & Sacerdote, B. (2005). Work and leisure in the U.S. and Europe: Why so different? (Discussion Paper No. 2068). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Institute of Economic Research.

- Atkinson, J. (1984). Manpower strategies for flexible organizations. Personnel Management, 16, 28-31.

- Atkinson, J. (1985). Flexibility, uncertainty and manpower management. Brighton, UK: University of Sussex.

- Berkhout, E. E., & van Leeuwen, M. J. (2004). International data base on employment and adaptable labour (IDEAL). Amsterdam: SEO.

- Blyton, P., & Morris, J. (1992). HRM and the limits of flexibility. In P. Blyton & P. Turnbull (Eds.), Reassessing human resource management (pp. 116-130). London: Sage.

- Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, E. (1999). Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme [The new spirit of capitalism]. Paris: Gallimard.

- Bolwijn, P. T., & Kumpe, T. (1990). Manufacturing in the 1990s— Productivity, flexibility and innovation. Long Range Planning, 23, 44-57.

- Casey, C., & Alach, P. (2004). “Just a temp?” Women, temporary employment, and lifestyle. Work, Employment and Society, 18, 459-480.

- Finegold, D., Levenson, A., & Van Buren, M. (2003). A temporary route to advancement? The career opportunities for low-skilled workers in temporary employment. In E. Appelbaum, A. Bernardt, & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Low-wage America: How employers are reshaping opportunity in the workplace (pp. 317-367). New York: Russel Sage.

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

- Goudswaard, A., Kraan, K. O., & Dhondt, S. (2000). Flexibility in balance: Flexibility and consequences for employers and employees. Hoofddorp, The Netherlands: TNO Arbeid.

- Herzberg, F. (1968, January/February). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review, 52-62.

- Hossfeld, K. J. (1995). Why aren’t high-tech workers organized? Lessons in gender, race, and nationality from Silicon Valley. In D. Cornford (Ed.), Working people of California (pp. 405432). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kunda, G., Barley, S., & Evans, J. (2002). Why do contractors contract? The experience of highly skilled technical professionals in a contingent labour market. Industrial and Labour Relations Review, 5, 234-261.

- Letourneux, V. (1998). Precarious employment and working conditions in the European Union. Dublin, Republic of Ireland: European Foundation for the Improvement of Working and Living Conditions.

- Looise, J. C., van Riemsdijk, M., & de Lange, F. (1998). Company labour flexibility strategies in the Netherlands: An institutional perspective. Employee Relations, 20, 461-482.

- Matusik, S. F., & Hill, C. W. L. (1998). The utilization of contingent work, knowledge creation, and competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 680-697.

- Olsen, K. M., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2004). Non-standard work in two different employment regimes: Norway and the United States. Work, Employment, and Society, 18, 321-348.

- Peters, T. (1999). The circle of innovation. New York: Vintage Books.

- Pink, D. H. (2002). Free agent nation: The future of working for yourself. New York: Warner.

- Purcell, K., & Purcell, J. (1998). In-sourcing, outsourcing, and the growth of contingent labour as evidence of flexible employment strategies. The European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 7, 39-60.

- Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and un-written agreements. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Saloniemi, A., Virtanen, P., & Vahtera, J. (2004). The work environment in fixed-term jobs: Are poor psychosocial conditions inevitable? Work, Employment and Society, 18, 193-208.

- Saxenian, A. (1996). Beyond boundaries: Open labor markets and learning in Silicon Valley. In M. B. Arthur & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era (pp. 23-39). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schilfgaarde, P., & Cornelissen, W. J. M. (1988). The flexible firm: Opportunities and instruments for enhancing employee flexibility. Assen, Drenthe, The Netherlands: Management Studies.

- Stone, K. V. W. (2002). Knowledge at work: Disputes over the ownership of human capital in the changing workplace. Connecticut Law Review, 34, 721-763.

- Storrie, D. (2002, March). Temporary agency work in the European Union (Consolidated Report). Dublin, Republic of Ireland: European Foundation for the Improvement of Working Life and Living Conditions.

- Thornthwaite, L., & Sheldon, P. (2004). Employee self-rostering for work-family balance. Employee Relations, 26(3), 238-254.

- Torka, N. (2004). Atypical employment relationships and commitment: Wishful thinking or HR challenge? Management Revue, 3, 324-343.

- Torka, N., & Schyns, B. (2007). On the transferability of “traditional” satisfaction theory to non-traditional employment relationships: Temp agency work satisfaction. Employee Relations, 29, 440-457.

- Van Velzen, M. (2004). Learning on the fly: Worker training in the age of employment flexibility. Amsterdam: Thela Thesis.

- Van Velzen, M. (in press). Roads to flexicurity: Balancing flexibility and security in value-added logistics.

- Volberda, H. W. (1996). Toward the flexible form: How to remain vital in hypercompetitive environments. Organization Science, 7, 359-374.

- Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies: analysis and antitrust implications—A study in the economics of internal organization. New York: Free Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.