This sample The Merger Paradox Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Firms that are quoted on the stock markets of Western industrialized economies undertake hundreds of acquisitions (or mergers) every year. Sometimes, however, these hundreds rapidly grow into thousands. Curiously, the lion’s share of these acquisitions—depending on the industry, roughly between 65% and 85%—repeatedly fail to create shareholder value. This is the so-called “merger paradox”: If most of these acquisitions fail, why then do they at times remain so popular? A large part of this research-paper will be devoted to answering this question. We will discuss several theories of the firm such as theories that try to establish the drivers of firm behavior—in which executives play a dominant role—in order to see whether they can account for systematically thick acquisitions. We will subsequently discuss the possible effects of such mergers both on the firms concerned and on the economy as a whole. We will conclude with a discussion of management and policy implications of the merger paradox both at the level of business executives and public policymakers, including policies to prevent the paradox from manifesting itself again in the future. First, however, we will have to consider the stylized facts of merger performance at some length as this is so neglected in the management literature that newcomers to the field find it difficult to accept that a majority of (merger-active) firms appear to violate the assumptions of Economics 101.

Finding adequate answers to the merger paradox is important for several reasons. First, explaining firm behavior that is not economically rational yet common must have implications for received theories of the firm. Second, understanding the determinants of merger failure is helpful in developing effective corporate strategies in daily business practice. Third, since merger failure not only appears to express itself in terms of profits or innovation but also in terms of shareholder value, understanding merger dynamics is also helpful to investors. Finally, since merger failure at times is so widespread, understanding its causes is helpful for public policymakers, too. Thus, the entry provides practical information to executives in various branches of the economy: firm managers and fund managers as well as public managers.

Given this importance, it is rather noteworthy that most merger research has focussed on prescriptive rather than explanatory issues. That is, it has focused on how to improve the chances for merger success without really considering why so many mergers fail. Economists in this respect have simply evaded the question while relying on the assumption that nonoptimal decisions will “automatically” be corrected by the market’s disciplinary apparatus. Management researchers normally assume that mistakes can be corrected by (a) becoming aware of them; and (b) taking corrective action. Thus, it is assumed that managers can learn from mistakes—that’s the whole point of providing management education—and will not commit the same errors in the future as committed in the past. Commentators and authors of management texts have come up with a bookcase full of monographs informing us that careful preparation of the deal and much attention for integration after it would significantly improve the sad fate of mergers. Assuming that executives would be capable, just like the rest of us, to learn from mistakes, indeed, it is curious why—collectively—they have not demonstrated such learning over time. Mergers during the second half of the 1990s failed to the same extent as those of the 1960s and 1980s, if not to a larger extent.

Theories fail because of wrong assumptions—in this case with respect to the efficiency of markets, capital markets in particular, as well as with respect to determinants of human and thus management behavior. With respect to management decision making, these assumptions include the rationality assumption (for mainstream economics) or the bounded rationality assumption (for mainstream management theory). Capital markets are assumed to at least be efficient enough to make sure that executives strive for the best and only the best—in case of failure, they will be removed from office through takeover by a more efficient party.

This research-paper reaches the conclusion that the typical executive’s discretion should not be overestimated while the power of strategic imperatives should not be underestimated. In particular, the research-paper shows that when making such important decisions as those concerning merger, executives follow mimetic routines. Modern decision-making theory suggests that the avoidance of regret, the existence of strategic uncertainty, and the many opportunities to share the blame for failed mergers combine to seduce executives into imitating early movers—even if the prospects for wealth creation are dim.

The important things to keep in mind are that most mergers occur during merger waves; that only mergers among equals, and the acquisition of small, private firms by much larger ones are generally able to create wealth; that the further down a merger wave, the smaller the chances for success; that many mergers are unbundled after some time; and that in the case of mergers strategic rationality may diverge from economic rationality. More elaborate discussions of the issues covered in this research-paper can be found in Schenk (2006).

Merger Waves And Merger Performance

The striking thing about mergers is that they appear in waves. Between 1900 and 2000, there have been five such waves, three of which occurred after World War II. During the fifth wave, which had its rising tide from 1995-2000, American and European firms invested no less than 9,000 billion U.S. dollars. At the time, by way of comparison, acquisition expenditures by American and European firms were about seven times larger than Britain’s annual gross domestic product (GDP). On average, they amounted annually to about one fifth of U.S. GDP. Investments in mergers and acquisitions were approximately equal to 60% of their gross investments in machinery and equipment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation), and they easily outpaced those in research and development (R&D). A sixth wave manifested beginning in 2004, approaching the peaks of the fifth.

Thus, when dealing with the phenomenon of mergers, we are dealing with one of the most important—perhaps the most important—phenomenon of Western-style capitalism. If these mergers would create wealth, they would significantly contribute to the wealth of nations. Alternatively, should they go wrong, they would significantly hurt economies.

By now, the performance of mergers and acquisitions has been the subject of many dozens of studies, both in terms of real-value effects and in terms of shareholder value effects. By far, most studies have estimated shareholder value effects, using mostly stock market data and predicted normal returns as controls. Those studies that estimated real-value effects, however, have used more sophisticated data—usually drawn from firm statements—as well as more sophisticated methodologies. They have commonly used size and industry-matched control groups of nonmerging firms and/or ceteris paribus extrapolations of premerger performance. Although the findings of the various studies are not completely consistent, the general tendencies are clear. Besides, since both shareholder value and real-value studies—under certain restrictions—share similar conclusions, findings must be regarded as convincing.

Real Value

Perhaps the most important study of real-value merger effects is Dickerson, Gibson, and Tsakalotos (1997). For a panel of almost 3,000 U.K.-quoted firms that undertook acquisitions during the period 1948-1977, they found a systematic detrimental impact on company performance as measured by the rate of return on assets. More specifically, for the average company, the marginal impact of becoming an acquirer was to reduce the rate of return relative to nonacquirers by 1.38 percentage points (i.e., in the year of the first acquisition). Taking all subsequent acquisitions into account, acquiring firms experienced a relative reduction of 2.90 percentage points per annum. Since the mean return across all nonacquiring firms was 16.43%, this translates into a shortfall in performance by acquiring firms of 2.9/16.43, which is around 17.7% per annum.

This finding is not an exception. On the contrary, the most common result of merger-performance studies is that profitability and productivity, variously measured, do not improve as a result of merger. In many cases, efficiency does not improve or in fact declines, while in other cases it improves but not faster than would have been expected in the absence of merger. Since it is unlikely that the market power of merging firms declines after merger, any decline in profitability can be taken to indicate a decline in efficiency. Mergers and acquisitions appear to lead to less product variety while increases in the rate of technological progressiveness appear to remain at bay. Acquisition variables, after size, leverage, return on assets, and liquidity are controlled for, appear statistically significant, negative predictors of R&D intensity adjusted for industry. Market-share growth seems to slow down after a merger as well, while acquired firms lose market share against control groups of firms that remain independent. For instance, among the world’s 18 largest pharmaceutical firms, 11 out of 12 that participated in mergers lost combined market share between 1990 and 1998 whereas all six of those that had not merged gained market share (“The New Alchemy,” 2000).

Generally, even in an industry as fragmented as banking, the consensus concerning mergers and acquisitions (M&As) is that at best they lead to very little improvements in productive efficiency. Exceptions exist, of course, but they mostly pertain to mergers among very small, locally active banks. The findings suggest that the larger the merging banks are, especially when their size is beyond a still quite limited asset size of $10 billion, the smaller the chances for cost improvements. Indeed, for the largest banks in Europe and elsewhere, there appears to be no significant relationship between size and profitability.

Overall, several methodological criticisms may be brought against some of the established types of merger-performance studies (for example, see Calomiris, 1999). Yet, the evidence appears consistent across studies of financial as well as nonfinancial mergers and across time periods.

In fact, the only substantial exception to the findings just reported is a study by Healy, Palepu, and Ruback (1992) which investigates postmerger cash flow for the 50 largest nonfinancial U.S. mergers consummated between 1979 and 1984. By adopting the same index as Ravenscraft and Scherer (1987) did in the most revealing study to appear before the fifth merger wave (and arguably the best ever), Healy et al. purported to have refuted the Ravenscraft and Scherer findings. Their results showed that around two thirds of these mergers had cash-flow improvements ex post. However, Healy et al. deflated this index of performance by a market-based asset variable that can imply cash-flow/asset performance indicator gains relative to the market even when cash flows are deteriorating relative to those of peer companies, namely if acquiring company market value falls relative to the general market—which, indeed, appeared to be the case.

Moreover, it appeared that many assets were sold after the merger. Upon closer inspection, these assets appeared to have high book values but low sell-off revenues. This clearly suggests cooking of the books, in the sense that some assets might have been artificially inflated in order to prevent high write-ups to goodwill accounts. Sell-offs in this case will result in relatively favorable cash flow/asset performance during the postmerger years. Indeed, when the authors in a later (substantially less well-known) study added acquisition premiums to the deflator, results deteriorated significantly. On average, the mergers studied now appeared to be unprofitable and/or insignificantly different from sector indicators.

Shareholder Value

Similar results are obtained when the focus is on shareholder instead of real wealth. A review of 33 earlier studies by Mueller (2003) found that while target shareholders usually gain from acquisitions, acquirer shareholders almost always lose, especially in the long run. Generally, the longer the postmerger assessment period, the more negative shareholder returns appear. Usually, positive abnormal returns are only evident for a few days around the event (and even then, only when preevent build-ups of share prices are underestimated), but taking this as evidence requires a strong belief in the Efficient Market Hypothesis (that securities markets excellently and quickly reflect information about individual stocks and about the stock market as a whole). Mueller’s findings were confirmed by various studies on European mergers.

Interestingly, when taken together the data suggest the possibility of intertemporal (rather than intersector) variations in merger performance. One of our own studies, focusing on European mergers, divided a sample into 5-year cohorts (beginning with 1995 and ending with 1999). For 400 postmerger days each, the study revealed that “earlier” acquisitions perform better (or less badly) than “later” acquisitions. The 1995 cohort reached positive results but all others were in the negative, the 1999 cohort performing worst of all; it saddled its shareholders with an average cumulative loss of almost 25%. Similarly, in a study of about 12,000 (American) acquisitions from 1980 to 2001, Moeller, Schlingemann, and Stulz (2003) found that while shareholders lost throughout the sample period, losses associated with acquisitions after 1997 were “dramatic.”

The periodicity found in these studies is consistent with newer work by Carow, Heron, and Saxton (2004) investigating stockholder returns for 520 acquisitions over 14 industry-defined merger waves during 1979-1998. They found that the combined returns for target and acquiring shareholders were higher for mergers that took place during the early stages of these waves. Well-performing acquirers all made their acquisitions during these same stages.

Finally, it is worthwhile to refer to a recent study assessing the added effects of 93 studies with 852 effect sizes (i.e., germane bivariate correlations) with a combined n size of 206,910, where n was derived from adding the number of companies on which each of the 93 studies relied (King, Dalton, Daily, & Covin, 2004). Observed zero-order correlations between the variables of interest were weighted by the sample size of the study in order to calculate a mean weighted correlation across all of the studies involved. The sample included both shareholder and real-value studies (with the latter limited to studies of the effects on return on assets, return on equity, and return on sales). Abnormal (shareholder) returns for acquiring firms appeared to be only positive and significant at day 0. Except for an insignificant positive effect for an event window of 1-5 days, all others were negative and significant (i.e., for event windows of 6-21 days; 22-180 days; 181 days-3 years; and greater than 3 years). Similarly, all results for acquiring firm’s return on assets, return on equity, and return on sales were either insignificant or negative.

In conclusion, the most robust discriminator of success and failure is intertemporality: the further down the merger wave, the more disappointing economic results become.

Summary and Implications

Obviously, when most but not all mergers fail to boost profits, efficiency, shareholder value and so on, it becomes of importance to learn which factors are associated with success or failure. Unfortunately, the economics and management literatures have not been able to produce systematic evidence in this respect, except for studies that tracked productivity effects in cases in which specific plants were transferred from one owner to another. But with respect to “real” mergers, about all we can say, following the metaanalysis performed by King et al. (2004) mentioned previously, is that postmerger performance is not related to type of firm (conglomerate vs. specialized); relatedness between target and acquiring firm (in terms of resource or product-market similarity); method of payment (cash vs. equity); and acquisition experience.

However, the findings from merger performance studies also raise more fundamental questions. If mergers that do not create wealth, or even destroy it, are so common and recurrent, one is led to accept either one of two propositions. Either corporate executives are not sufficiently equipped to run the firms they are heading, or they do not care as much about the economic results of their actions as economic theory predicts they should.

Determinants Of The Merger Paradox: Received Theory

Conventional economic decision-making theory cannot provide us with an adequate answer. It relies on the assumption that nonoptimal decisions are “automatically” corrected by the market’s disciplinary apparatus so that, by implication, mergers cannot fail in a structural sense. In modern variants of this neoclassical interpretation of the economy, firms are disciplined by the workings of the so-called market for corporate control. Underperforming firms—i.e., firms that undertake uneconomic mergers—will become targets of more efficient firms that through a takeover will take them back to efficiency optimization. Constraints to takeovers should, therefore, be eliminated. Thus, takeovers in this view are regarded as instruments that the economy uses en route to further wealth—instruments of economic progress. Notice that an important implicit assumption is that firms cannot display perverse behavior; for example, they cannot through a takeover of potential way layers turn the market for corporate control to their advantage.

All approaches that rest on economic utilitarianism and methodological individualism have great difficulties in coping with economic subjects that repeatedly refrain from maximizing economic returns. Management theory often assumes that, in the end, an executive has control over his or her own policies. For instance, smarter executives are believed to outperform dumb executives. Chance is almost never included in analyses while the impact of outside forces and institutions is seriously underestimated. Success or failure is attributed to the CEO.

Yet, two theories have come to be accepted as explanations for uneconomic mergers, both of which put an emphasis on the possible effects of too much decision-making freedom for executives.

Agency Theory

Back in the 1930s Berle and Means (1968) observed that for joint-stock firms, ownership had come to be largely separated from control. This opened the possibility of a conflict of interest between principals (owners) and their agents (managers). Whereas owners were assumed to have as their sole interest the maximization of profits, managers might aim for the maximization of personal utility, for example through steadily pushing for larger size (which was assumed to be positively correlated with managerial income) or for perquisites (which would add to managerial status). Faced with disappointing merger results, agency theory soon proposed that managers were undertaking mergers in order to boost their firm’s size rather than profits while using up funds that should have been distributed to shareholders.

In addition, whereas principals are expected to be risk neutral, since they can diversify their shareholdings across multiple firms, agents are assumed to be risk averse as their jobs and incomes are inextricably tied to one firm. This would imply that—apart from the size-effect on income—uneconomic mergers would be undertaken in order to prevent loss of job and/or status.

To a certain extent, the empirical evidence is consistent with agency-theory expectations. Managerial income and perks, as well as status, rise with the size of the firm, especially if size has been generated by acquisitions. However, mergers may threaten agents’ employment security, as becomes evident from the fact that many CEOs are laid off once the merger wave is over and firms come to realize that many acquisitions have been a waste of funds or have even brought counterproductive results. Moreover, the picture that is depicted of managers is particularly negative. It is somehow hard to believe that the large number of uneconomic mergers should be explained by the fact that managers are disguising and distorting information and misleading or cheating their principals. On the contrary, managers may be just like ordinary people—they may enjoy performing responsibly because of a personal need for achievement, while interpreting responsibility as something that is defined in relation to others’ perceptions (such as would be proposed by “stakeholder theory”).

Hubris Theory

Others have tried to explain the merger paradox by suggesting that hubris may lead managers to expand company size through mergers beyond those which maximize real shareholder wealth, and/or to disregard dismal experiences with earlier mergers. Such overconfidence may grow when past success (even if this was quite coincidental) leads to a certain degree of arrogance and a feeling of supremacy, which in turn leads to overpayment. Indeed, the height of bidding premiums appears to depend on whether the bidders can boast a successful premerger record in terms of market-to-book and price-to-earnings ratios (Raj & Forsyth, 2003). Prior success breeds overpayment, smaller bidder returns and higher target returns, thus relative failure. Not only were the premiums paid by hubris firms on average 1.5 times higher, their acquisitions were also paid with paper in 64% of the cases whereas the control group managed just 23%—suggesting that the risks of the deal were in part carried over to target shareholders.

An earlier project by Hayward and Hambrick (1997) used two more indicators of hubris, namely the extent of recent media praise for the CEO and the size difference between the CEO’s pay and the other executives’ pay in their firms. They reached similar conclusions. Malmendier and Tate (2003) classified CEOs as overconfident when they held company options until expiration. Such CEOs were found to be more likely to conduct mergers while the market reacted more negatively to their takeover bids relative to those of others.

Conclusion

Both agency and hubris theory, the latter in particular, would play an important part in an explanation of uneconomic mergers and acquisitions. However, both are static theories. Clearly, in cross sections, empire builders as well as hubris CEOs will be found to run the highest risk of merging their firms to the brink of failure. But this cannot account for the fact that empire building and overconfidence manifest only under particular circumstances. Also, they take an individualistic point of view, tacitly assuming that a decision maker’s actions are independent from those of others. Thus, while possibly correct in a substantial number of cases, agency and hubris theories cannot clarify why (uneconomic) mergers should occur in waves—which is what they do.

Determinants of The Merger Paradox: New Theory

What is needed, therefore, is a theory that can explain why firms undertake uneconomic mergers and why they do so at approximately identical intervals. For this, we have to abandon the maxims of economic rationality and accept more fully the fundamentals of, especially, behavioral theory.

According to behavioral theory, uncertainty or lack of understanding with respect to goals, technologies, strategies, payoffs, and so on—all typical for modern industries—are powerful forces that encourage imitation. When firms have to cope with problems with ambiguous causes or unclear solutions, they will rely on problemistic search aimed at finding a viable solution with little expense. Instead of making decisions on the basis of systematic analyses of goals and means, organizations may well find it easier to mimic other organizations. Most “important” mergers are undertaken by large firms. These firms normally operate in concentrated industries and are usually active in several of those industries at the same time. In the typical situation of single market or multimarket oligopoly, which involves both interdependence of outcomes and strategic uncertainty, adopting mimetic routines is therefore a likely way for solving strategic decision-making problems. Moreover, organizations with ambiguous or (potentially) disputable goals will be likely to be highly dependent upon appearances for legitimacy.

Reputation

This latter point is implied in one of the more interesting models of recent decision theory in which Scharfstein and Stein (1990) assume that there are two types of managers: “smart” ones who receive informative signals about the value of an investment (e.g., a merger), and “dumb” ones who receive purely noisy signals. Initially, neither these managers nor other persons (i.e., stakeholders) can identify the types, but after an investment decision has been made, stakeholders can update their beliefs using the following two pieces of evidence:

- Whether their agent has made a profitable investment

- Whether their agent’s behavior was similar to or different from that of other managers

Given the quite reasonable assumption that there are systematically unpredictable components of investment value, and that whereas dumb managers simply observe uncorrelated noise, smart managers tend to get correlated signals since they are all observing a piece of the same “truth,” it is likely that the second piece of evidence will get precedence over the first. Since these signals might be “bad” just as well as “good,” smart managers, however, may have all received misleading signals. Since stakeholders will not be able to assess or even perceive these signals, they will refer to the second piece of evidence in assessing the ability of “their” managers. Now, if a manager is concerned with her reputation with stakeholders, then it will be natural for her to mimic a first-mover as this suggests to stakeholders that she has observed a signal that is correlated with the signal observed by the first-mover—which will make it more likely that she is a smart manager.

The more managers that adopt this behavior, the more likely it will be that bad decisions will be seen as a result of a common unpredictable negative component of investment value. In other words, the ubiquitousness of the error will suggest that all managers were victims of a bad signal. Erring managers will subsequently be able to share the blame of stakeholders with their peers. In contrast, managers who take a contrary position will ex ante be perceived as dumb. They will therefore be likely to pursue an investment opportunity if peers are pursuing it—even if their private information suggests that it has a negative expected value. Thus, Scharfstein and Stein’s (1990) model explains why, according to Keynes (1936), conventional wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.

Rational Herding

This result is not generally dependent on reputational considerations. Whereas Scharfstein and Stein’s (1990) model is essentially an agency model in which agents try to fool their principals and get rewarded if they succeed, others have addressed the imitation phenomenon as a consequence of informational externalities. In such models, each decision maker looks at the decisions made by previous decision makers in making his or her own decision and opts for imitating those previous decisions because the earlier decision makers may have learned some important information. The result is herd behavior—that is, a behavioral pattern in which everyone is doing what everyone else is doing.

Herding models are essentially models that explain why some person may choose not to go by his or her own information, but instead will imitate the choice made by a previous decision maker. Following Banerjee (1992), suppose that—for some reason—the prior probability that an investment alternative is successful is 51% (call this alternative if) and that the prior probability that alternative i2 is successful is 49%. These prior probabilities are common knowledge. Suppose further that of 10 firms (i.e., firms called A through J), 9 firms have received a signal that i2 is better (of course, this signal may be wrong), but one firm that has received a signal that i2 is better happens to choose first. The signals are of equal quality, and firms can only observe predecessors’ choices but not their signals. The first firm (firm A) will clearly opt for alternative i . Firm B will now know that the first firm had a signal that favored i while its own signal favors i2. If the signals are of equal quality, then these conflicting signals effectively cancel out, and the rational choice for firm B is to go by the prior probabilities, i.e., choose ir Its choice provides no new information to firm C, so that firm C’s situation is not different from that of firm B. Firm C will then imitate firm B for the same reason that prompted firm B to imitate firm A, and so on: all 9 follower firms will eventually adopt alternative i . Clearly, if firm B had fully relied on its own signal, then its decision would have provided information to the other 8 firms. This would have encouraged these other firms to use their own information.

Thus, from a broader perspective, it is of crucial importance whether firm A’s decision is the correct decision. If it is, then all firms will choose for the “right” alternative, but if it is not, all firms will end up with a “wrong” decision. Also, the result of this game is dependent on chance: were firms B through J to have had the opportunity to choose first, things might have come out entirely different. However, when translated into our merger problem, if alternative i2 is set equal to “do not undertake a merger,” then A’s action (“merger”) will always be the first to be observed as a deviation from actual practice, thus prompting firms B through J to respond. The mechanism is especially clear when a first and a second firm have both chosen the same i 1 0 (where the point 0 has no special meaning but is merely defined as a point that is known, i.e. observable, to the other firms). That is, the third firm (firm C) knows that firm A must have a signal since otherwise she would have chosen i = 0. Firm A’s choice is therefore at least as good as firm C’s signal. Moreover, the fact that B has followed A lends extra support to A’s choice (which may be the wrong choice nevertheless). It is therefore always better for C to follow A.

The main virtues of this type of model—sometimes called cascade models—are

- that some aspects of herd behavior can be explained without requiring that a decision maker will actually benefit from imitating earlier decision makers (which would be the case if undertaking some action is more worthwhile when others are doing related things); and

- that it is possible that decision makers will neglect their private information and instead go by the information that is provided by the actions of earlier decision makers (or the prior probabilities).

Regret

The entry thus far has shown that the intricacies of information diffusion in sequential games can cause imitation despite the fact that a follower’s private information would indicate a deviation from the trajectory that seems to have been started. Notice, however, that they are couched in a positive payoff framework. Furthermore, they make use of binary action sets implying that only correct and incorrect decisions are possible and that a small mistake incurs the same loss as a large mistake. The introduction of a regret framework relaxes these conditions and increases the plausibility of models of herding behavior. In a seminal series of experiments, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) found that people systematically violate two major conditions of the expected utility model’s conception of rationality when confronted with risk: the requirements of consistency of and coherence among choices. They traced this to the psychological principles that govern the perception of decision problems and the evaluation of options. Apart from the fact that it appears to matter substantially in which frame a given decision problem is couched (or presented; formulated), even to the extent that preferences are reversed when that frame is changed, choices involving gains are often risk averse and choices involving losses involve risk taking. Thus, it appears that the response to losses is more extreme than the response to gains. Kahneman and Tversky’s “prospect theory,” of course, is consistent with common experience that the displeasure associated with losing a sum of money is greater than the pleasure associated with gaining the same amount.

Consequently, it is likely that the contents of decision rules and standard practices will be biased in such a way that they favor the prevention of losses rather than the realization of gains. Thus, behavioral norms that carry this property are more likely to be chosen as Schelling’s so-called focal points. In practice, this will mean that firms are likely to adopt routines that imply a substantial degree of circumspection. A similar degree of circumspection is likely to develop if decision makers are concerned with the regret that they may have upon discovering the difference between the actual payoff as the result of their choice and “what might have been” the payoff if they had opted for a different course of action. Regret in this case may be defined as the loss of pleasure due to the knowledge that a better outcome may have been attained if a different choice had been made. Under conditions of uncertainty, a decision maker will modify the expected value of a particular action according to the level of this regret.

Minimax-Regret

Various authors have suggested that one way of expressing this is by adopting a minimax-regret routine. Let us assume that a decision maker knows the payoffs for each decision alternative but that he is completely ignorant as to which state of nature prevails. The minimax-regret routine then prescribes that he selects the strategy that minimizes the highest possible regret assuming that the level of regret is linearly related to the differences in payoff. The minimax-regret criterion thus puts a floor under how bad the decision maker would feel if things go wrong. Moreover, doing so will protect him against the highest possible reproach that can be made by those stakeholders who assess the decision’s utility based on the true state of nature.

When put into a framework of competitive interdependence, this develops as follows. Given that firm A announces the acquisition of firm B, and that this acquisition for some reason attracts attention of its peers (rivals), firm C will have to contemplate what the repercussions of this initiative for its own position might be. Suppose that there is no way that C can tell whether A’s move will be successful or not. A’s move could be genuinely motivated by a realistic expectation that its cost position will improve or by a realistic expectation that its move will increase its rating with stakeholders or even its earnings. That is, A’s competitiveness position vis-à-vis its peers might be improved as a result of that move, say in terms of a first mover advantage. But then again, it might not. For example, A’s move might be purely motivated by the pursuit of managerial goals, or it might simply be a miscalculation caused by hubris. What is firm C to do?

Suppose that A’s move will be successful, but that C has not reacted by imitating that move itself (which we will call scenario a). To what extent will C regret not having reacted? Alternatively, suppose that A’s move will not be successful but that C has imitated it, solely inspired by the possible prospect of A’s move being a success (scenario fi). To what extent will C regret this when the failure of A’s move becomes apparent? Within a minimax-regret framework, it is likely that C’s regret attached to scenario a will be higher than the regret attached to scenario fi. For in scenario a, C will experience a loss of competitiveness, while in scenario fi its competitive position vis-à-vis A will not have been harmed. Of course, C could have realized a competitive gain in scenario fi had it refrained from imitation, but in terms of the minimax-regret model its regret of having lost this potential gain is likely to be relatively small. The implication is that under conditions of uncertainty a strategic move by firm A will elicit an imitative countermove by its rivals—even if the economic payoffs are unknown.

We conclude that a decision maker who is using a minimax-regret routine will imitate actions of earlier decision makers that are regarded as significant. Thus, if—for some reason—a first decision maker within a strategic group has decided to undertake a merger, a second decision maker may follow suit even if his or her own information suggests otherwise. Evidently, such imitation may lead to cascades that will last very long if not forever. In a sense, mergers and acquisitions have then become taken-for-granted solutions to competitive interdependence. It implies that firms may have become locked into a solution in which all players implicitly prefer a nonoptimal strategy without having ready possibilities for breaking away from it.

Even if some firms do not adopt minimax-regret behavior, it will be sensible for them to also jump on a merger bandwagon. For cascading numbers of mergers and acquisitions imply that the likelihood of becoming an acquisition target increases. Thus, given the finding that relative size is a more effective barrier against takeover than relative profitability, firms may enter the merger and acquisition game for no reason other than to defend themselves against takeover. Needless to say, such defensive mergers will amplify the prevailing rate of mergers and acquisitions. The cascade will inevitably stop as soon as (a) the number of potential targets diminishes, which is a function of the intensity of the cascade, and (b) the disappointing merger returns decrease the chances for obtaining the financial means necessary for further merger investments.

Conclusion

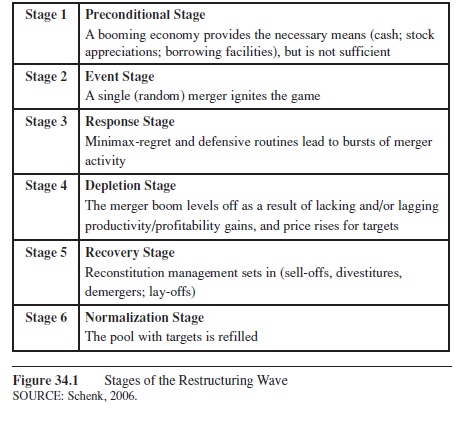

The existence of strategic interdependence under uncertainty, conditioned by the availability of funds, compels managements to undertake mergers even if these will not increase economic performance. Inertia may prevail for long periods, but as soon as an initial, clearly observable move has been made by one of the major players, it is likely that other players will rapidly follow with similar moves. With multimarket oligopoly omnipresent, and given the increasing weight assigned to stock-market performance appraisals, the ultimate result may be an economy wide merger boom. Eventually, many firms will find themselves stuffed with acquisitions that were neither meant nor able to create wealth. Consequently, after the strategic imperatives have receded, firms will start licking their wounds by undertaking corrective actions. In the short run, they are likely to look for cheap and easy alternatives, like economizing on all sorts of expenses (e.g., labor, R&D). In the medium run, they will spin off many of the acquisitions done during the boom—sometimes at great cost. Figure 34.1 depicts the different stages of the restructuring wave.

Mergers that have been undertaken for minimax-regret or defensive reasons have been called “purely strategic mergers.” These are mergers that are intended to create strategic comfort when faced with the uncertain effects of a competitor’s moves, rather than economic wealth (or, for that matter, monopoly rents). It is precisely for this reason that it would be futile to wait on the so-called learning capacities of organizations to improve economic merger performance. In a system dominated by a few, such purely strategic mergers are simply part of the game—and since these mergers on average may only turn out to be wealth-creating by chance, uneconomic mergers will also be the order of the day especially whenever firms are baiting each other into a merger wave.

Figure 34.1 Stages of the Restructuring Wave SOURCE: Schenk, 2006.

Figure 34.1 Stages of the Restructuring Wave SOURCE: Schenk, 2006.

Implications

If uneconomic mergers are unavoidable in a free-market system, the real question for firms is how to minimize the negative effects. One possibility consists of shedding part of the risk on the target’s shoulders. Indeed, during the fifth-merger wave, the majority of merger investment was financed by an exchange of shares. More generally, issuing new shares for financing an acquisition shifts the burden of failure to shareholders whereas the employment of financial reserves or borrowing has a much more immediate effect on the firm’s health.

Another way out, or at least in part, consists of pursuing virtual rather than “real” mergers. In the majority of cases, once environmental pressures have diminished, the acquisition no longer makes sense. Thus, it would be natural to proceed to sell-off. However, most acquisitions are legitimized by pointing at potential integration synergies. If such integration, indeed, has been pursued, it will become more costly to demerge again once this is deemed prefer-able—which, gathering from the data, is the case in more than half of all acquisitions. The solution to this dilemma would be to forge a virtual merger. That is, whereas the strategy game requires the firm to participate in an ongoing merger wave, business logic would prohibit the same firm to materially integrate its newly acquired entity in the parent organization. If, in due course, the acquisition appears to have met the requirements of business rather than strategy logic after all—after the merger wave has reached its summit—there will still be many chances to proceed to integration. The schizophrenia is embedded in taking decisions to acquire while at the same time taking measures to sell off the acquired entity again as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, beginning during the fourth-merger wave in the late 1980s, a complete new industry has grown that has specialized in facilitating spin-offs of previously acquired subsidiaries or divisions. Sometimes labeled locusts, these private-equity companies (PECs) benefit from the large number of failed mergers by offering to arrange break-ups. A cynical observer would note that the whole process looks like a carousel of detours. Perhaps, it would have been more efficient had the original mergers not taken place at all.

Indeed, it has been estimated that the fifth merger wave may have implied efficiency losses of 2,100-3,600 billion U.S. dollars, with the lion’s share falling in 1999 and 2000. Since these losses are real efficiency losses rather than numbers based on perceptions of failure (i.e., on stockmarket statistics), we are talking about serious money here. For example, for the United States and Europe, such losses amount to approximately 3% of cumulative GDP. An additional and perhaps even more far-reaching result is the knock-on effect on investment and consumption spending. If funds do not generate wealth, this implies that they do not create economic growth. It could be argued that the billions expended on mergers do not vanish from the economic process. Shareholders at the receiving end may—instead of creating a consumption bubble or overindulging themselves in conspicuous consumption—reinvest their newly acquired pecuniary wealth in investment projects that do create economic wealth. If so, then we would merely have to worry about a retardation effect. Still, such an effect may be significant, since an accumulation of retardation effects—and this is exactly what is likely to happen during a merger wave—is called a recession.

Current competition and antitrust policies, though designed to prevent or punish corporate behavior that is eating into society’s wealth-generation processes, are currently not able to protect the economy from such behavior. Taking uneconomic mergers into account has not become easier as competition authorities have changed their focus from the once cherished public-interest criterion to efficiency, productivity, and contestability considerations (Hess & Adams, 1999). In many cases, moreover, it has become modern to see as the ultimate goal of competition policy the maximization of consumer surplus. This is clearly a much too narrow interpretation of wealth. Reappraising mergers in terms of the public rather than the consumer’s interest, therefore, would seem an elegant line of public-policy approach to mergers.

Summary And Conclusions

This entry has suggested that the omnipresence of failed mergers is not surprising since uneconomic mergers seem a natural result of competition among the few. Such competition encourages strategic rather than economic behavior; that is, behavior that is not primarily driven by the wish to create wealth but by the behavioral peculiarities of strategic interdependence. Even if only some firms adopt a minimax-regret rationale, others will be forced to jump on merger bandwagons for defensive reasons. Under certain conditions, the result will be an extremely costly merger wave. Once this becomes evident, firms need to take corrective actions. Consequently, such merger waves are followed by periods of restructuring, large-scale divestment and layoffs. The sheer size of the problem may be sufficient to provoke economic recessions. Whereas the observed effects are rooted in the high levels of economic concentration that have become typical for modern economies, therefore a matter of competition policy, current merger regulations may not be the preferred means of control. Merger regulations have been designed to prevent as many harmful mergers as possible while preserving economically efficient mergers. As long as the consumer’s interest will remain the main vehicle for defining the wealth of nations, however, competition economists and authorities will be led away from the most pervasive problematic effect of mergers. Rather, one would want to see competition policy return to its roots by putting the public interest at centre stage.

References:

- Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797-817.

- Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. (1968). The modern corporation and private property (Rev. ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

- Calomiris, C. W. (1999). Gauging the efficiency of bank consolidation during a merger wave. Journal of Banking & Finance, 23(2/4), 615-621.

- Carow, K., Heron, R., & Saxton, T. (2004). Do early birds get the returns? An empirical investigation of early-mover advantages in acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, 25(6), 563-585.

- Conn, R. L., Cosh, A., Guest, P. M., & Hughes, A. (2005). Why must all good things come to an end? The performance of multiple acquirers. Working paper. Cambridge, UK: Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1992). A behavioral theory of the firm (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Dewey, D. (1996). Merger policy greatly simplified: Building on Keyes. Review of Industrial Organization, 11(3), 395-400.

- Dickerson, A. P., Gibson, H. D., & Tsakalotos, E. (1997). The impact of acquisitions on company performance: Evidence from a large panel of UK firms. Oxford Economic Papers, 49(3), 344-361.

- Dickerson, A. P., Gibson, H. D., & Tsakalotos, E. (2003). Is attack the best form of defence? A competing risk analysis of acquisition activity in the UK. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 27(3), 337-357.

- Dietrich, M., & Schenk, H. (1995). Co-ordination benefits, lock-in, and strategy bias. In Management report 220. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

- Greer, D. F. (1986). Acquiring in order to avoid acquisition. Antitrust Bulletin, 41(1), 155-186.

- Haleblian, J., & Finkelstein, S. (1999). The influence of productive experience on acquisition performance: A behavioral learning perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 29-56.

- Hayward, M. L. A., & Hambrick, D. C. (1997). Explaining the premiums paid for large acquisitions: Evidence of CEO hubris. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(1), 103-127.

- Healy, P. M., Palepu, K. G., & Ruback, R. S. (1992). Does corporate performance improve after mergers? Journal of Financial Economics, 31(2), 135-175.

- Hess, M., & Adams, D. (1999). National competition policy and (the) public interest (Briefing Paper No. 3). Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: National Centre for Development Studies, Australian National University.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision making under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. London: Macmillan.

- King, D. R., Dalton, D. A., Daily, C. M., & Covin, J. G. (2004). Meta-analyses of post-acquisition performance: Indicators of unidentified moderators. Strategic Management Journal, 25(2), 187-200.

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2003). Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. Working Paper. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Graduate School of Business.

- Moeller, S. B., Schlingemann, F. P., & Stulz, R. M. (2003). Do shareholders of acquiring firms gain from acquisitions? Working Paper 9523. Washington: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Mueller, D. C. (2003). The finance literature on mergers: A critical survey. In M. Waterson (Ed.). Competition, monopoly and corporate governance. Essays in honour of Keith Cowling (pp. 161-205). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. The new alchemy. (2000, January 22). Economist, 354(8154), 61-62.

- Raj, M., & Forsyth, M. (2003). Hubris amongst UK bidders and losses to shareholders. International Journal of Business, 8(1), 1-16.

- Ravenscraft, D. J., & Scherer, F. M. (1987). Mergers, sell-offs, and economic efficiency. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1990). Herd behavior and investment. American Economic Review, 80(3), 465-479.

- Schelling, T. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Schenk, H. (2006). Mergers and concentration. In P. Bianchi & S. Labory (Eds.), International handbook of industrial policy (pp. 153-179). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.