This sample Winning In Asia Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Between 2001 and 2006, Asia’s economies accounted for over half the world’s growth in gross domestic product (GDP). During this period, the United States contributed 19% of the total increase in global GDP; Asia’s contribution was 21% (Economist, 2006). But even these statistics understate Asia’s real importance in the world economy because current exchange rates do not take into account the fact that a dollar buys much more in most Asian countries than it would in America or Europe. Measured in purchasing power (PPP) terms, Asia would look even more important as a growth engine.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that companies headquartered in developed markets, where economic growth is no more than 3% or 4% in boom times and zero or negative when things are slow, are looking to tap into Asia’s rapid expansion. China, which has consistently notched double-digit growth rates for more than a decade and, more recently India, which grew by 8% in 2006, look particularly attractive—especially as together they are home to over 2.4 billion people. That is not to forget the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN)—which has an additional population of 560 million—and Japan, which has a population of 120 million and is still the second-largest economy in the world. But what will it take for Western companies to benefit from Asia’s potential, as it becomes an ever more powerful force in the world economy?

More Than A Manufacturing Center

One approach so far adopted by many multinational companies has been to take advantage of lower Asian costs by transferring their basic manufacturing to Asian countries.

China in particular has become the “factory of the world,” doubling its share of global manufacturing to almost 7% in the decade to 2003 while most of the G8 developed nations saw their shares in global production fall. Other Asian countries are also benefiting from the global relocation of manufacturing: during 2006 Intel, for example, announced it was investing $1 billion in new factories in Vietnam, while Flextonics, the firm that manufactures many of Hewlett Packard’s printers, invested $150 million in just one of its new Malaysian plants.

Even if productivity might be lower than at home, the potential cost advantages Asia offers are enormous. The average monthly wages of a factory worker plus social security totals around $200 per month in Manila, around $150 in Bangkok, and just over $100 in Batam in Indonesia. Even in booming Beijing and Shanghai, where factory workers wages and social security costs often exceed $300 per month, this is still a fraction of the cost of wages in the United States or Europe.

For all the attractions of Asia as a low-cost manufacturing location, however, focusing on this aspect alone would greatly underplay Asia’s potential within a Western company’s strategy. Asia has at least three other ways in which it can play a major role in a successful global company.

First is the potential of Asia’s domestic markets as a source of new customers, rather than just as a production base for exports. Despite the preoccupation of many commentators with Asian products flooding into America and Europe, the major growth engine in most Asian economies is domestic demand. In 2006, for example, domestic demand contributed 8.3 points of China’s 10.2% growth; over 7 points of India’s 8% growth was accounted for by rising domestic demand; while in Indonesia 4.9 points of its 5% growth was attributed to growth in its home market. Asian consumers and businesses now offer serious potential as the customers of the future. To take just one example, more than 80 million mobile phones were sold in China alone last year, and today leading global companies like Nokia and Motorola rely on the Chinese market for a large slug of their sales (and even more of their volume growth). More and more companies will need to gear up to sell to Asia as a core market—perhaps even the key global battleground—rather than treating it as an afterthought.

Second, companies can grasp Asia’s potential as a source of new talent, not just a pool of low-skilled factory workers. In 2005, for example, there were 3.4 million new graduates from Chinese universities and colleges, three times the number graduating just 5 years ago. Last year, China passed the United States in terms of the total number of students enrolled in universities, so China now has more people studying for degrees than any other country in the world. The most popular majors were among the most relevant to the needs of commerce and industry. Business administration is the top choice, followed by computer science, law, finance, communications, medicine, and English. In the same year, more than 3 million people graduated from universities in India.

Again, some multinational companies have begun to tap into this potential in Asia. The large U.S. industrial services group Emerson, for example, has recognized that Asia must play a central role in supplying talent if it is to achieve its goal of increasing the number of engineers in its global staff from 6,000 to 9,000 before the end of 2007. The company recruited some 1,500 engineers in China alone in 2006 (Mitchell, 2007). SAP, the German company that is a world leader in the enterprise software on which most global companies rely, has over 3,000 employees in India engaged in software engineering. Many other companies have the potential to tap into Asia’s growing talent pool in the future.

Third, there is the potential to tap into Asian innovation. In the past, with notable exceptions, such as Sony of Japan or Creative Technology of Singapore, Asian companies and the local subsidiaries of multinationals were mostly importers of new technologies and innovative products and services. This has led some people to the misconception that Asia is fundamentally less creative than the West. Those who doubt Asia is creative need look no further than the fact that four of the great inventions that changed the world—gunpowder, the compass, paper, and printing—all originated in China. Over the past decade or so, research and development (R&D) spending in Asia has increased dramatically. In Japan and South Korea, the ratio of R&D spending to GDP outstripped the United States for the whole decade of the 1990s. And in China today about 1 million are people directly involved in R&D. Measured in PPP, China’s total R&D expenditure was estimated by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development to have reached $136 billion in 2006—the second highest in the world. Japan’s R&D spending was a further $130 billion. Both have been closing the gap on the $330 billion spent in the United States in the same year.

Some companies have also been taking advantage of this potential to tap into Asian innovation. Intel in China is a good example. It was one of the first companies to begin accessing China’s technological knowledge and R&D capabilities, setting up joint labs with Beijing University and Tsinghua University in 1995. In October 2000, Intel expanded its cooperation with Tsinghau, setting up programs that, according to the CEO Craig Barrett would “increase the breadth of knowledge in e-business and e-commerce through hands-on research projects that couple the latest technological tools with new business practices” (People’s Daily Online, 2000a). Since then, Intel has established three major research and development organizations in China: the Intel China Research center, focusing on human-computer interface research; the Intel China Software Labs, developing systems software for Intel products; and the Intel Architecture labs, an application development organization (People’s Daily Online, 2000b).

Western companies clearly have an opportunity to grasp the growing potential of Asia far beyond its role as a place to outsource manufacturing. Today, Asia can be an important source of new customers in fast-growing markets, provide a new pool of talent, and be a source of innovative ideas and technologies. Accessing this broader new potential of Asia, however, will certainly require more than simply setting up shop and presenting the same products that sell at home to eager consumers, hiring local talent, or investing in a network of innovation and design centers. Asian markets are highly competitive and rapidly changing. So repeating formulas worked in the past, or cloning approaches used at home, is unlikely to succeed. New strategies are required to deal with the changing realities of Asia. The remainder of this research-paper discusses the fundamental factors driving change in Asia’s competitive game and what successful new strategies will need to look like to reap Asia’s full potential. It lays out what will be required to respond to the challenges and grasp the opportunities that the changing face of Asia and its competitive environment is bringing in its wake.

Four Major Shifts In The Asian Competitive Environment

Four shifts occurring in today’s Asia are particularly significant: the demise of asset speculators, China’s scattering of the pattern of orderly Asian “flying-geese” development and India’s recent takeoff, the breakdown of national economic “baronies,” and the decay of “me-too” strategies.

The Demise of the Asset Speculators

Profitable strategies are supposed to draw their lifeblood from creating new value by finding ways to provide customers with goods and services that either better fit their needs or do so more efficiently than competitors’ goods and services. If we are honest, however, that was not the way a lot of companies in Asia made money during the 1990s boom. Instead, they grew rich through asset speculation: buying assets ranging from real estate to acquiring rival firms or building large manufacturing facilities and letting the rising prices of these assets swell the market value of their companies. Even as they continued to benefit from asset price inflation, too many senior managers in Asian companies were happy to bask in the illusion that they were creating new value through world-beating competitiveness and thriving in a dynamic, open market. The same was true for many of their multinational counterparts operating in the region whose management was more inclined to attribute their success to brilliant strategy and execution than to favorable market conditions.

The Asian financial crisis of 1997 shattered those illusions because, almost in a stroke, it removed the windfall of rising asset prices that had been the unspoken secret of success in many Asian businesses. Instead of capital gains, as asset prices rose year after year, Asian management faced a sustained period of asset price deflation. As banks and asset management companies were forced to share in the burden, the impact was delayed for years. But now, as Asian balance sheets have been reconstructed leaving the investment community chastened, the upper hand is shifting to those who can add the most value to the assets and resources they use and away from simply adding new capacity. The next round of Asian competition will reward those who can do more, do it differently, and do it for less, not those who build the largest corporate empires in Asia or assemble the biggest caches of assets on which to speculate.

China Scatters the “Flying Geese”; India Takes Off

A second major force of change in the Asian environment is the China-India factor. Asia’s traditional model of economic development was often described as “flying geese” in formation. Each country began by manufacturing and exporting simple, labor-intensive products like garments and shoes and assembling low-end products. As it accumulated more capital and know-how, it moved through products of intermediate complexity, and then to high-value-added products and services. As one country moved on to the next level of value-added products, another developing country took its place at the lower-value-added end. Japan led the flock, followed by Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Next came Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Albeit somewhat simplistic, this concept of national geese flying in formation underlies many government policies and corporate strategy. It shaped the pattern of what diversified Asian-owned companies invested in next and where multinationals located their activities in Asia.

Then along came China. The Economist magazine aptly summed up the result with a cartoon. It depicted a jet aircraft, piloted by a panda, zooming straight through the flock of Asian geese (Economist, 2001). China was not flying in the cozy formation; by the new millennium, it was undertaking activities ranging from simple manufacturing to design and manufacture of high-technology components and equipment, from making rag dolls and molding plastic toys to the fabrication or semiconductors and specialized machinery. And China is doing this on a scale large enough to redraw the competitive map.

More recently, the deregulation and opening up of India has added further to these pressures. Since this process began in the early 1990s and has gathered pace over the last 5 years, India has become a powerful force in reshaping the competitive playing field in Asia. But India’s growth has been concentrated in different industries than those that led China’s expansion. While China’s growth has largely been driven by the manufacturing sector, in India growth has been led by service and knowledge industries such as IT services, software design, and biotechnology. In these sectors India is moving rapidly from a low-technology to a high-technology competitor. For example, the Indian pharmaceutical company, Dr. Reddy’s, has already moved beyond supplying the world with generic versions of established drugs to become an innovator of new medicines. It is launching a new diabetes medication in 2010, is spending between 12% and 14% of its revenues on R&D, and is working on new treatments for oncology, metabolic disorders, cancer, cardiovascular illness, and obesity.

Now that the flying-geese model of where to locate low-and high-end operations respectively has been exploded and the neat formation is in disarray, companies will have to reevaluate the roles of each of their subsidiaries across Asia. With China and India now key players in the Asian game, the winners will be those who can offer to restructure their operations into a more integrated Asian jigsaw where each subsidiary in Asia supplies specialized components or focuses on particular activities within the overall supply chain.

This development represents a fundamental change in the Asian competitive environment because when companies review the footprint of their existing operations through the new lens of a more integrated Asian supply chain, they will often discover that their existing subsidiaries are in the wrong places with too much vertical integration and possible specialization in the wrong things.

Semiconductor companies are a good example of the kind of new strategy that will be necessary. Leading companies in this industry have had to abandon the historic set-ups where they made high-end chips in one country and low-end chips in another. They have had to restructure so that a subsidiary in one Asian country does the circuit design, a subsidiary in another country does photolithography, and a subsidiary in a different location does the so-called “back-end packaging” of the final chip. These kinds of pressures for redrawing the map of Asia have huge implications for the strategies that will succeed in the future.

The Breakdown of National Economic Baronies

Asia’s division into highly segregated national markets, separated from each other by a mix of tariff and nontariff barriers, cultural and language differences, divergent choices about local standards, and regulatory differences between countries is legendary. Within this environment it made sense for companies to approach each national market as a separate competitive playing field. This behavior was reinforced by various forms of preference given by governments to their local companies through the allocation of licences, preferential access to finance, and other kinds of direct and indirect support. Likewise, multinationals historically approached Asia as a collection of separate national markets.

In this environment, local “country managers” often became local barons: each in charge of a highly autonomous subsidiary within the Asian network. Each baron fought for the investment of more resources in his business unit and argued the case for against sharing functions from procurement and manufacturing to distribution and marketing on the grounds that any such moves would reduce his ability to respond to the peculiarities of the local market. The result was a set of largely independent subsidiaries spanning Asia under the umbrella of a “global” parent.

Today each of these country subsidiaries is under threat from the rapid growth of cross-border competition in Asia. A potent cocktail of falling trade barriers, deregulation of national markets, and falling costs of transport and communication is now opening the door to new sources of competitive advantage based on cross-border economies of scale and coordination. The results are striking. Trade between Asian countries is now growing more than twice as fast as Asia’s trade with the rest of the world, reflecting a rapid increase in direct cross-border competition. And perhaps even more significantly, Asian companies have invested an average of almost $50 billion every year in building or acquiring operations in other countries since 1995 (despite the setback of the 1997 financial crisis). Much of this investment is in building beachheads in other Asian markets from which to mount attacks on yesterday’s national baronies. In the face of this onslaught, yesterday’s fragmented Asian strategies will become untenable.

The Decay of “Me-Too” Strategies

Primary consumer demand—from first-time purchasers of everything from cars to washing machines and mobile phones—accounts for a large part of the market when economic growth in an economy first takes off. During this phase, consumers are willing to accept standardized, basic consumer goods. If you have never before owned a refrigerator, the most basic box that keeps things cool at reasonable cost is acceptable. But once consumers move on to become second- or third-time purchasers, they look for features such as the exact performance, styling, color, and so on that suits their individual needs. Consumers begin to demand higher product quality and variety, not simply more volume. Whirlpool’s experience when it entered the Chinese market for domestic appliances a few years ago is a good example of this change. Contrary to its initial expectations, it quickly found that Asian consumers rejected last year’s American designs and technologies. Instead, they demanded environmentally friendly CFC-free refrigerators, washing machines with state-of-the art electronic controls, and integrated, wall-mounted air conditioners instead of the standard type that hung precariously from a window space (Clyde-Smith & Williamson, 2001).

The same is true of fast-moving consumer goods (like food or cosmetics) and services: once your basic needs are satisfied by the range of products and services you consume, you start to look for particular varieties, flavors, sizes, presentations, and so on, or services customized to your individual needs. Even Asia’s humble instant noodle now comes in more than 20 different flavors and a range of packaging from paper to styrofoam cups, not to mention pink “Valentine’s Day” and red and gold “Chinese New Year Limited Edition” varieties (Donnan, 2000). These trends are a simple fact of life illustrated by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: as consumers become richer, they want better and more customized offerings, not “more of the same.”

These trends now reach beyond Asia’s wealthy elite. Throughout much of Asia, the mass market has now reached a stage of development where consumers are no longer satisfied with reliable, but standard and often boring products and services. Even in China and India, countries with huge rural populations (estimated at 900 million and 700 million, respectively) that have been little touched by consumerism, hundreds of millions of urban consumers are now sophisticated buyers that demand goods and services with the innovative features, variety and customization that precisely fit their individual needs. Companies unable to provide more innovative, flexible products will literally be left on the shelf.

In parallel, a new generation of Asian consumers is entering the market. Unlike their parents, today’s so called “X” and “Y” generations have never lived through real hardship; they were born into a consumer society. As a result, they take an abundance of goods and services largely for granted. Their choices reflect a complex mix of demand for higher quality, fashion, a desire to express more individualism, and a “what’s new?” mentality. While the precise implications of serving this new consumer generation will vary by industry, it is safe to say that they will demand even greater variety, customization, and innovation from suppliers than today’s mainstream consumers.

Despite all these changes, the Asian consumer is unlikely to abandon his or her traditional nose for value. Nor are Asian business buyers going to forget their historic emphasis on costs. But in the next round of competition in Asia, a strategy based solely on churning out high standard products in high volumes is unlikely to be a winner—even if the price is low. The new environment will demand that

winning companies succeed in pursuing a strategy of being different from competitors, as well as better; decisively “setting themselves apart from the competition” with a wider range of product options, better customer segmentation, and more customized offerings and stronger brands to signal differentiation from competitors.

Formulating The Right Strategic Responses

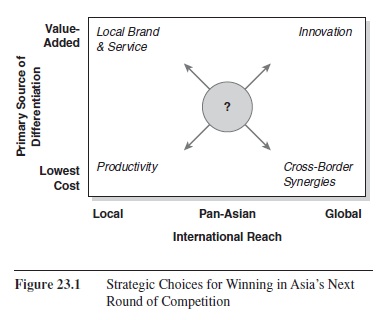

Asia’s new potential and the fundamental changes taking place in Asia’s competitive environment together demand new strategies. Clearly, there is no single recipe for winning the new competitive game in Asia. But the new reality of Asia demands that managers stake out their territory on mix of four core ingredients: improved productivity; local brand and service; innovation; and internationalization designed to reshape the Asian playing field and reap cross-border synergies. Figure 23.1 displays the strategic options.

Figure 23.1 Strategic Choices for Winning in Asia’s Next Round of Competition

Figure 23.1 Strategic Choices for Winning in Asia’s Next Round of Competition

A New Productivity Drive

Given the demise of asset speculation as a way of underpinning Asian profits and increasingly intense competition from local companies in China, India and cross-border rivalry within Asia, a key element in future Asian strategy must be to enhance efficiency of Asian operations through productivity gains—especially in neglected “overhead” areas beyond the factory gate such as administration, sales, and distribution.

A recent study I conducted on a sample of consumer-goods multinationals operating in Asia found that at an average of $75 million sales, their unit overhead was a staggering 300% higher than Asian rivals of comparative size. In fact, in a number of cases the overhead burden on foreign subsidiary expended just in dealing their foreign headquarters was higher than the total overhead of the local Asian competitors!

In many multinationals, overhead burdens rose during the 1990s when expansion at almost any cost was the name of the game. Companies recruited armies of staff to make sure support functions such as sales, administration, and distribution did not create bottlenecks or hinder the running of their expensive new factories. But as we enter a new round of Asian competition just described, it will not be enough for companies to rely on high productivity in manufacturing and routine operations alone. The productivity of their Asian competitors is increasing across a wide range of activities. A study by the Conference Board estimated that between 2000 and 2006 labor productivity in China rose at an average rate of over 10% per annum; in India the comparable figure was 4.5% (accelerating to 6.3% in 2006); even the most mature Asian economy, Japan, managed over 2% productivity growth (Giles, 2007).

In order to maintain their historic competitive advantage relative to Asian rivals, multinationals will have to be more assiduous about deploying advanced systems—in customer relationship management, logistics, and administration; “soft technologies”—to bring their Asian operations up to world-best-practice productivity outside core manufacturing and basic service operations. They will no longer be able to afford to follow the old adage that “Asia’s different” as an excuse for inefficient administration and low-productivity support and service activities.

Renewed Focus on Brand Building and Service Quality

As “me-too” strategies decay and Asian consumers demand more variety, customization, and service, there will be a growing need for the capability to deliver an improved product or service experience “on the ground” to every individual customer in Asia. Simultaneously, there will be a need to signal improved service to consumers and differentiate offerings from competitors by strengthening the equity of the brands in Asia market by market and customer by customer. The need for strategies to strengthen brand differentiation will be given further impetus as local Asian companies start to build or acquire their own brands—a trend that is well underway (see Figure 23.2).

Sometimes the rise of Asian brands in recent years has gone unnoticed by observers outside Asia. How Americans or Europeans realize that the highly successful clothing brand “Giordano”—a name that evokes European couture—is created and owned by a Hong Kong company. Are they aware that another fast-growing clothing brand, “British India” with retail outlets throughout the United States and Europe, is owned by Malaysian entrepreneur Pat Liew? It is time to forget the idea that Asian companies will forever lack their own brand and remain subcontract suppliers to established Western players.

Figure 23.2 Some Asian Brands on the Rise

Figure 23.2 Some Asian Brands on the Rise

As Asian companies begin to play the brand-building game, they often find ways to generate brand equity more quickly and more cheaply than their competitors thought possible. The powerful Banyan Tree brand, for example, was achieved with a relatively limited advertising budget. Instead, Banyan Tree made a concerted effort to provide travel journalists with easy-to-use press packs and interesting editorial copy to publish in their magazines. The cost of this public relations was relatively low compared to advertising, while the credibility of editorials in magazines was vastly higher than an advertising pitch. Banyan Tree’s Edwin Yeow has also remarked that editorial coverage was more effective in conveying the “holistic Banyan Tree experience” (Chua, Williamson, & DeMeyer, 2003). Banyan Tree further leveraged public relations to build its brand by entering its properties in competition for all major travel-industry awards and by taking its entry into these competitions seriously, with the right backup from senior management. As early as 1997, barely 2 years after its launch, Banyan Tree started its winning streak of a series of highly coveted international awards and accolades given by the travel industry and various publications for its resorts and spa. These awards proved invaluable in building a strong brand at low cost.

Other Asian companies, meanwhile, have built their brands cheaply and quickly by finding marketing channels with a high impact-to-cost ratio. When embarking on a brand-building campaign, multinationals often automatically gravitate to TV advertising. The total costs of building a brand through TV advertising can be daunting, and it’s not necessarily the highest impact per dollar of spending. As old marketing hands know well, it’s not only how many people you reach, but also the quality of the target audience in terms of their purchasing power and potential interest in the product and service, as well as the time you have your brand in front of them. TV, as a mass medium, often scores low on both audience quality and the time for which the audience is exposed to the message. Acer is again a good example of a company that was quick to see the value of exploring alternative marketing channels beyond TV. For more than a decade, it has put its Acer name on the luggage trolleys at Asia’s airports: both the “heavy luggage” trolleys and the small carts used inside Asia’s massive airport terminals after check-in to shift hand luggage and duty-free purchases.

Compared to the mass of Asian TV viewers, people traveling through airports include a high concentration of potential customers for Acer’s PCs: both business buyers and more affluent consumers who can afford to travel by air for leisure. The terminal carts therefore score highly as a channel to reach the target audience. Just as important, think about how long these potential customers are exposed to Acer’s message. It takes 5 to 10 minutes to walk from the check-in or arrival hall to the gate in sprawling modern airports. So the potential customer has the Acer name and tagline prominently displayed in front of him or her for a period equivalent to between 10 and 20 TV slots of 30 seconds! The impact-to-cost ratio of this “airport cart” channel has, not surprisingly, proved high.

There are at least two lessons for multinationals seeking to win in Asia in the next round of competition. First, they will not be able to take their brand premium for granted. As Asian competitors build stronger brands of their own, multinationals will have to increase their investment in brands in Asia. Better localization of branding, marketing, and service will also be required. Second, marketing managers in multinationals will need to reconsider how to match their Asian rival’s ability to reduce the cost of brand building using new, perhaps even unorthodox, communication channels.

As local brands become stronger, multinationals will also have to improve their ability to adapt their brands to better fit Asian consumer preferences if they are to win future competitive battles. The perils of failure to adapt are well illustrated by the experience of McDonald’s in the Philippines when competing with the local company Jollibee. Despite that fact that McDonald’s has been established in the Philippines for over 15 years, Jollibee maintains stronger brand awareness than its global rival and has some 600 outlets (30% more than McDonald’s). Starting from its base in ice-cream parlors, Jollibee entered the fast-food business with McDonald’s look-alike facilities and kitchens. Their secret of success was a product range better adapted to the Filipino palate than the global hamburger, with many more varieties of chicken and garlic and soy sauce in the burgers. To fight back, McDonald’s was forced to adapt its own menu much more sensitively to local tastes.

Concurrent with more local adaptation, however, winning Asia’s new competitive game will also require multinationals to simultaneously achieve better cross-border synergies between their subsidiaries in different Asian countries. Balancing these potentially contradictory pressures will demand a careful balancing act.

Reaping Cross-Border Synergies and Driving Consolidation

We have already seen that there is now a relentless competitive pressure on yesterday’s protected national baronies in the new Asian competitive game. If this new form of competition is not to undermine margins, better exploitation of cross-border synergies between different subsidiaries in Asia will be required. This will mean accelerating pan-Asian and global integration, leaving behind yesterday’s scatter of isolated national subsidiaries and facing up to country barons who resist a loss of independence.

As China continues to scatter the flying geese and India continues down the growth path, companies will need to rethink the role of different subsidiaries and locations within the overall Asian jigsaw. Rather than a loosely connected portfolio of largely self-sufficient national companies, each subsidiary will need to be refocused on a more specialized set of activities within a new Asian network that leverages the specific advantages and knowledge within each location.

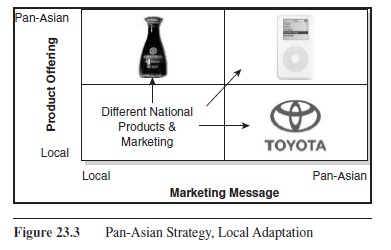

Figure 23.3 Pan-Asian Strategy, Local Adaptation

Figure 23.3 Pan-Asian Strategy, Local Adaptation

At the same time, product and brand portfolios will need to be restructured to achieve the right balance between local adaptation versus the commonality and integration required to reduce costs. This requires some tricky choices about both the extent of variation in product specification and marketing message, as well as the interaction between the two. The four main alternative strategies are summarized in Figure 23.3.

Most companies start off in the bottom left of Figure 23.3, with a local product and a local brand. In building, a global brand might look attractive to use the same product and the same marketing message everywhere in the world you want to sell. Sometimes when consumer behavior is quite similar across the world, such as with the Apple iPod, this works well. But frequently building a pan-Asian or global position requires adapting the product or the marketing behind the brand to the unique preferences of consumers in different countries or regions.

Japan’s leading brand of soy sauce, Kikkoman, for example, uses the same product formulation everywhere in the world—its differentiation comes from the a rich, complex flavor that comes from being naturally brewed instead of being chemically produced by combining hydrolyzed vegetable protein with salt, water, corn syrup, and artificial coloring. The marketing message varies widely across world markets: In Asia it is sold as a dipping sauce; in the United States it is sold as flavoring for minced meat in ham-burgers and in casseroles; and in Australia it is marketed as a barbeque marinade for seafood. The product is globally standard, but the marketing varies by country (see the upper left of Figure 23.3).

Toyota, by contrast, used the same marketing message for its core brand everywhere in the world: unrivalled reliability combined with value for money, captured in brands like “Corolla.” But the product sold under these common brands is differently engineered to adapt the cars for everything from rough roads in Australia to lower price points in India and Malaysia. The marketing is standardized globally, while the product is globally adapted (see the lower-right quadrant of Figure 23.3).

As competition from strengthening local firms combines with pressures to reduce costs by reaping cross-border economies across Asia, choosing and implementing the right positioning in Figure 23.3 is becoming critical.

In many industries, succeeding in the new competitive game in Asia will also mean taking advantage of the window of opportunity that is opening to drive consolidation of Asia’s fragmented supply base. This window for industry consolidation is opening because more intense competition from China and India along with the elimination of the protective barriers around national markets is putting increasingly intense pressure on Asian companies to become more efficient and more focused about where they invest their resources in the future. This means that more and more companies will be forced, however reluctantly, to dispose of businesses where they lack the scale and the prospect of building sufficient depth of capabilities to compete in the next round (Mody & Negishi, 2001).

This will create a new supply of businesses for consolidators to mop up that was not there in the past. At the same time, it will be important to create a focused portfolio of businesses so that resources are not spread too thinly. Each business in the portfolio will need to be of sufficient scale to justify the fixed-cost investments in assets, technology, and knowledge necessary to keep up with global leaders. To succeed in this environment, winning firms in Asia will need well-honed capabilities for quickly identifying, assessing, and executing overseas acquisitions and then reshaping these into a fully integrated business.

Innovating in Asia

With the decay of me-too strategies and the resulting increased emphasis on innovation amongst their local Asian rivals, multinationals will not only have to exploit transfer innovative technologies and products into Asia more rapidly, but will also have to ramp up their own innovation activities in Asia. Rather than just exporting innovations and new technology developed at home, American and European multinationals will need to restructure their innovation processes to benefit from the availability of high-quality researchers and engineers at lower cost, as well as to learn more from their Asian operations (Doz, Santos, & Williamson, 2001).

One of the key things multinationals need to learn if they are to win in Asia the next round of competition will be “cost innovation.” This refers to their capability to use Asia’s low costs in novel ways to deliver high technology at low cost, variety at low cost, and speciality products at low cost—not just to cut the prices of standard products. Consider some examples of the kinds of cost innovation Asian firms, especially the emerging Chinese competitors, have achieved (Zeng & Williamson, 2007). Chinese computer maker, Dawning, rapidly gained market share with an innovative move that applied the technology of supercomputers to everyday network servers. Huawei successfully penetrated the global market by offering high-technology, Next-Generation Networks to telecom operators at a cost well below its competitors. China International Marine Containers applied path-breaking research to replace the tropical hardwood in containers with a synthetic material. Shinco deployed its experience in using advanced technology for squeezing quality images out of substandard, pirated VCDs to produce the world’s best portable DVD player. Rather than shelling out $400,000 a piece for digital direct X-ray machines, Zhongxing applied different high technologies to develop cost-effective direct digital radiography machines for the everyday radiography needs of a hospital. Pearl River used sophisticated, flexible manufacturing methods and high technology for drying timber to improve value for money in the market for pianos.

Learning the secrets of cost innovation from Asia can also help multinational companies better unlock new potential customers in Asia and developing markets in other parts of the world. Prahalad described this strategy as unlocking “the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid” in a book by that name published in 2004. In a nutshell, the idea is that companies can make money for their shareholders while simultaneously helping lift people out of the poverty trap by devising ways to deliver more value at much lower cost. He argued that if incumbent multinationals were to take advantage of this opportunity, they have to reexamine six widely shared orthodoxies of Western management:

- The poor are not target customers.

- The poor cannot afford and have no use for the products and services sold in developed markets.

- Only developed markets appreciate and will pay for new technology.

- The bottom of the pyramid is not important for the long-term viability of their business.

- Managers are not excited by business challenges that have a humanitarian dimension.

- Intellectual excitement is in the developed markets.

In the past, too few multinational companies have seen the potential of leveraging innovations from their Asian operations across other markets. Even those who have done so, frequently fail to recognize Asia as an important, ongoing source of innovation. The primacy of the home base and the “parent” organization as the fount of innovation dies hard.

Forward-thinking multinationals are, however, beginning to reassess the potential role of Asia in their global innovation strategies. Consider, for example, General Electric (GE) Medical Systems. Today, GE Medical’s Chinese subsidiary is responsible for the bulk of GE’s global R&D in CT medical scanners. China also accounts for a slice of GE Medical’s global R&D effort in magnetic resonance and X-ray ultrasound diagnosis equipment. In 2002, GE Medical’s subsidiary in Wuxi fully developed and launched the LOGIQ Book—a high-end ultrasound diagnosis machine the size of a laptop PC. Despite being portable, it was capable of high-quality color imaging with performance that matched existing bulky, desktop machines. Using the cost innovation capabilities available in China, GE Medical was able to put high technology into a portable, cost-effective offering. Perhaps not surprisingly, the product has proven a global hit. As its local general manager put it, “We have a strong belief: that is, if we can produce something at ‘China cost,’ but also of high quality, high functionality, and high technology, it will become a very popular mass-market product, and it will be truly welcomed by customers” (Yang, 2003). Seeking to replicate this success, GE Medical has now established 28 specialist-development laboratories, each focusing on a different product line across five SBUs in China.

In a very different industry, the global drinks group Diageo (owners of Smirnoff Vodka, J&B Scotch, and Bailey’s Irish Cream) has established an innovation group in Hong Kong whose role is to seek out emerging trends and technologies within the region for global innovations. Johnson & Johnson has begun to deploy innovative manufacturing processes designed in Asia across its subsidiaries in the region rather than implementing solutions born in the west. Over the last few years, more than 100 global R&D centers have been established in China alone by leading multinationals such as HP, Microsoft, and Motorola. Others need to follow these pioneers.

Another strategy for accessing these cost-innovation capabilities might be to acquire an Asian company with a proven track record in this area. This route seems to be increasingly popular. According to the accounting firm Grant Thornton U.K., in the 12 months to June 30, 2006, some 266 international companies from 41 different countries made acquisitions in China alone. It is notable that the high-technology sector accounted for the largest number of deals within the total (Grant Thornton International, 2007). It seems that international competitors are beginning to see the potential of accessing Asian technological capabilities to deliver innovation at lower cost.

Asia’s New Competitive Game

Given Asia’s broad potential to play a major role in a multinational company’s strategy, as an efficient manufacturing base, a rapidly growing source of potential new customers, a deep new pool of talent, and a unique source of innovation, winning in Asia is becoming critical for more and more Western companies. But there should be no doubt that the requirements to win in Asia are changing: It will take a different kind of company to succeed in Asia’s next round of competition than might have prospered in the past. Unquestionably, this will require determined efforts among multinationals operating in Asia to raise their game in the four key areas of strategy discussed previously: developing a new productivity drive, creating a renewed focus on brand building and service quality, reaping cross-border synergies and driving consolidation, and innovating in Asia. The mix of these strategies will vary by industry and company. But whatever route a company chooses to take into Asia’s future, the new reality of competition in Asia is unavoidable: Amid renewed opportunity, there will be a sharper divide between the winners and losers. Just being there will not be enough.

References:

- Bartlett, C. A., & Goshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Bartlett, C. A., Goshal, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). Transnational management (4th ed.). New York: Irwin-McGraw Hill.

- Borrus, M., Ernst, D., & Haggard, S. (Eds). (2000). International production networks in Asia. London: Routledge.

- Chua, C. H., Williamson, P. J., & DeMeyer, A. (2003). Banyan tree resorts and hotels: Building and international brand from an Asian base (Case No. 02/2003-5087). Fontainebleau, France: INSEAD.

- Chen, M. (1995). Asian management systems. London: Routledge.

- Clyde-Smith, D., & Williamson, P. J. (2001). Whirlpool in China (A) Entering the world’s largest market (Case No. 08/2001-4950). Fontainebleau, France: INSEAD.

- De Meyer, A., Mar, P., Richter, F.-J., & Williamson, P. J. (2005). Global future: The next challenge for Asian business. Singapore: Wiley.

- Donnan, S. (2000, Feburary 14). Indofood wants us to say it with noodles. Financial Times, p 24

- Doz, Y., Santos, J., & Williamson, P. (2001). From global to metanational: How companies win in the knowledge economy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- (2001, August 25). A panda breaks the formation, p. 65.

- (2006, October 19). The alternative engine: Asia and the world economy. Retrieved August 27, 2007, from http://www.economist.com/business/displaystory.cfm?story_id=8049652

- Friedman, T. L. (2005). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

- Giles, C. (2007, January 23). Emerging economies must work hard to keep success story going. Financial Times, p. 8.

- Grant Thornton International. (2007). Buying into China—41 countries enter the dragon. Retrieved August 24, 2007, from http://www.gti.org/pressroom/articles/pr_08212006.asp

- Hofer, M. B., & Ebel, B. (Eds.). (2006). Business success in China. New York: Springer.

- Kim, L. (1997). Imitation to innovation: The dynamics of Korea’s technological learning. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Krugman, P. (1994, November/December). The myth of Asia’s miracle. Foreign Affairs, 62-78.

- Kugler, R. (2000). Marketing in east Asia: The fallacies and realities. In D. L. Dayao (Ed.), Asian business wisdom (pp. 4754). Singapore: Wiley.

- Mathews, J. A. (2001). Dragon multinational: A new model for global growth. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mitchell, T. (2007, January 9). Chinese talent key to company hiring spree. Financial Times, p 26.

- Mody, A., & Negishi, S. (2001, March). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions in east Asia. Finance and Development, 6-11.

- People’s Daily Online. (2000b, October 25). Intel helps establish e-business projects at Tsinghua University. Retrieved August 24, 2007, from http://english.people.com.cn/english/ 200010/25/eng20001025_53583.html

- People’s Daily Online. (2000a, October 26). Intel China labs set up. Retrieved August 24, 2007, from http://english.people. com.cn/english/200010/26/eng20001026_53589.html.

- Prahalad, C. K. (2004). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty through profits. Philadelphia: Wharton School Publishing.

- Redding, G. (2001). The smaller economies of Pacific Asia and their business systems. In A. Rugman & T. Brewer (Eds.), Oxford handbook of international business (pp. 71-84). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Roll, M. (2005). Asian brand strategy: How Asia builds strong brands. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Williamson, P. J. (2004). Winning in Asia: Strategies for the new millennium. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Yang, G. (2003, May). GE medical in China. Sino Foreign Management, 31-34.

- Zeng, M. & Williamson, P. J. (2007). Dragons at your door: How Chinese cost innovation is disrupting global competition. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.