This sample Psychopathy and Antisocial Personality Disorder Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The history of psychiatric nosologies has been scattered with a variety of terms used to describe individuals with serious personality pathology that leads them to engage in ways considered repugnant to the social mores of the time. Manie sans delire, moral insanity, moral imbecility, degenerate constitution, congenital delinquency, constitutional inferiority, sociopathy, antisocial personality disorder, and psychopathy are among the many semantic variations of the main theme. While the diagnostic labels have continued to evolve for more than 200 years, the personality characteristics and behaviors that they denote have remained relatively unchanged. The most commonly ascribed characteristics include a pronounced disorder of affective or moral functions, accompanied by irresponsibility, impulsivity, and a propensity to engage in behavior that brings them into conflict with society – and often the law. However, the disorder is typically absent of any appreciable alteration in cognitive functioning, such as perception, judgment, imagination, or memory.

The term psychopathy has been most consistently used in the psychological and psychiatric research and clinical literature; therefore, that is the term that will be used in this research paper. The paper begins with a brief overview of the history of psychopathy and its clinical and behavioral implications before turning to a discussion of the relevance of psychopathy for criminology.

What Is Psychopathy?

First and foremost, psychopathy is a serious personality disorder. Personality disorder is defined as “an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence.. .is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment” (American Psychiatric Association 2000, p. 629). Personality disorders are manifested by difficulties in at least two of the following four areas: cognitions (capacity to think and reason), affectivity (expressed emotion), interpersonal functioning (ability to engage in meaningful and stable relationships), and impulse control (the ability to adapt and control behavior). Psychopathy is a personality disorder that is characterized by deficits in interpersonal functioning, expressed emotion, and behavior. Characteristics of the disorder in the interpersonal domain include an elevated sense of importance, proneness to pathological lying and manipulation, and superficiality. The deficits associated with expressed emotion include having a flat level of affect, limited capacity for empathy, remorse, and feelings of guilt. Low levels of anxiety are also noted. The behavioral manifestations of the disorder include an elevated need for stimulation, proneness to boredom, impulsivity, irresponsibility, and a failure to take responsibility for their own actions. Such individuals tend to lack conventional social values which repeatedly bring them into contact with authority figures and, oftentimes, the law.

Millon and colleagues (1998) noted that “psychopathy was the first personality disorder to be recognized in psychiatry. The concept has a long historical and clinical tradition, and in the last decade a growing body of research has supported its validity.. .” (p. 28). Early on, the term psychopathy was used to refer to a range of personality disorders (“psychopathic personalities”) that were seen to be extreme forms of normal personality. General descriptions of people who share the characteristics found in the modern conceptualization of “psychopathy” (see Cleckley 1941) have been found in ancient writing. Scholars and practitioners alike have debated the merits of conditions such as those characterized by so-called antisocial features for as long as attempts have been made to classify mental disorder. For example, the term “manie sans de´lire” (i.e., mania without confusion of the mind), which Pinel coined in the 1700s to describe patients whose affective faculties were disordered, was criticized as early as 1866 for only having use in court (Falret 1866). As noted at the outset, over the years, a number of different labels have been used for the condition; all of the terms that have been used are pejorative, and there is little doubt that each would conjure up very negative images for people. The term with the longest clinical tradition is “psychopathy.” As such, it has been the subject of considerable research and scholarly writing. While sharing characteristics with psychopathy, the contemporary condition antisocial personality disorder is much broader and is based more on behavioral features than on some of the traditional personality characteristics associated with psychopathy.

In 1941, the American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley described the condition of psychopathy in his now classic book the Mask of Sanity. He identified 16 characteristics of psychopathy which he drew from the literature and his clinical experience:

- Superficial charm and good intelligence

- Absences of delusions and other signs of irrational thinking

- Absence of “nervousness” or psychoneurotic manifestations

- Unreliability

- Untruthfulness and insincerity

- Lack of remorse or shame

- Inadequately motivated antisocial behavior

- Poor judgment and failure to learn from experience

- Pathological egocentricity and incapacity for love

- General poverty in major affective reactions

- Specific loss of insight

- Unresponsiveness in general interpersonal relations

- Fantastic and uninviting behavior, with drink and sometimes without

- Suicide rarely carried out

- Sex life impersonal, trivial, and poorly integrated

- Failure to follow any life plan

Initially this disorder was known as psychopathy or psychopathic personality; however, by the introduction of the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II 1968), the condition was labeled “Personality Disorder, Antisocial Type,” although the diagnostic criteria still closely resembled those described by Cleckley (1941).The term “antisocial personality disorder” was first introduced in 1980 in the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980) and has remained with the most recent edition of the DSM, published in 2000 (DSM-IV-TR; APA 2000). Beginning with the introduction of DSM-III in 1980, the DSM criteria began to focus almost exclusively on behavioral features. The current criteria for antisocial personality disorder are as follows:

- Evidence of conduct disorder before age 15

- A pervasive pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others since the age of 15, as indicated by three or more of the following:

- Failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behaviors, as indicated by repeatedly performing acts that are grounds for arrest

- Deceitfulness, as indicated by repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for personal profit or pleasure

- Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead

- Irritability and aggressiveness, as indicated by repeated physical fights or assaults

- Reckless disregard for safety of self or others

- Consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor financial obligations

- Lack of remorse, as indicated by being indifferent to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from another

Ogloff (2006) noted that while the current diagnostic conceptualization of antisocial personality disorder is based largely on behaviors, traditionally the focus of psychopathy was on the interpersonal and affective deficits. Regrettably, the disorder has become a diagnostic category for behavioral difficulties pertaining to criminality. Moreover, as will be discussed below under implications, far more people (particularly prisoners) meet the criteria for a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder than is warranted.

To complicate matters further, the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10; World Health Organization 1992) uses both personality traits and behaviors for the diagnosis of dissocial personality disorder, conceptually similar to psychopathy. The criteria for this disorder are:

- Callous unconcern for the feelings of others and lack of the capacity for empathy

- Gross and persistent attitude of irresponsibility and disregard for social norms, rules, and obligations

- Incapacity to maintain enduring relationships

- Very low tolerance to frustration and a low threshold for discharge of aggression, including violence

- Incapacity to experience guilt and to profit from experience, particularly punishment

- Marked proneness to blame others or to offer plausible rationalizations for the behavior bringing the subject into conflict with society

- Persistent irritability

As compared to antisocial personality disorder, dissocial personality disorder places more emphasis on traditional psychopathic personality features. In particular, dissocial personality disorder emphasizes deficits of affect or expressed emotion, which have traditionally been seen as among the central personality features of psychopathy.

How will antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy fare in the upcoming revision to the DSM, the DSM-5? The proposed changes to the DSM-5 include substantial shifts in how personality disorders are defined and organized (see www.dsm5.org). Included in these changes are significant modifications to the criteria for antisocial personality disorder. The proposed DSM-5 revisions, referred to as antisocial personality disorder/dissocial personality disorder available at the time of writing, shift the diagnostic focus more toward the traditional interpersonal and emotional aspects of psychopathic personality and rely less heavily on the behavioral, or criminal actions of the individual. While the revision process is yet to be completed, clarification and differentiation between antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy are warranted lest the confusion will continue.

The Operationalization Of Psychopathy

The Hare Psychopathy Instruments

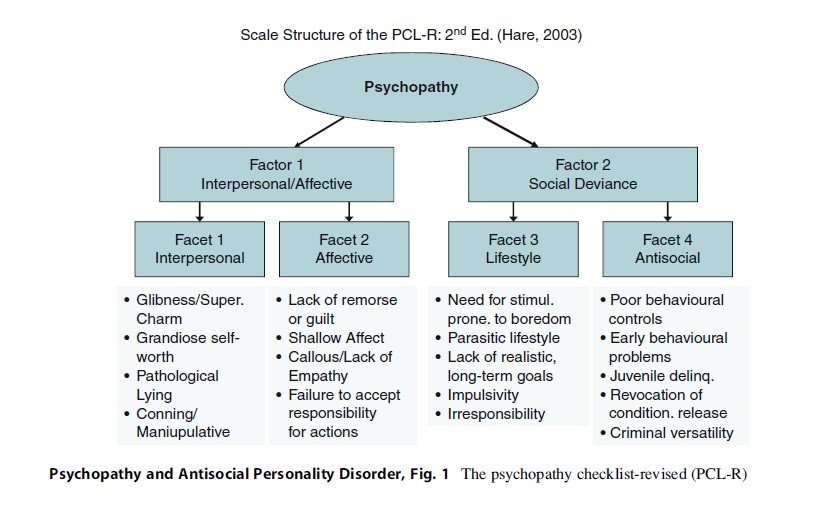

Although the criteria for antisocial personality disorder have changed with each edition of the DSM, Dr. Robert Hare developed the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL-R; Hare 1980, 2003) to reliably and validly assess the traditional construct of psychopathy described by Cleckley (see Fig. 1).

The PCL-R is a symptom-construct rating scale comprised of interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial features. It consists of 20 items, 18 of which comprise a two-factor, four-facet model (the two additional items do not load on either factor but do contribute to the total score). Each of these items is coded on a three-point ordinal scale (0 = does not apply; 1 = partially applies; 2 = definitely applies), such that total scores on the instrument range from 0 to 40. Scores on this instrument measure the extent to which an individual matches the prototypical “psychopath.” The PCL-R is a dimensional measure of psychopathic traits, and while it is true that many people may possess some of the characteristics to some extent, very few possess enough of the traits to be considered “psychopathic” (i.e., with scores above 30 on the instrument). Indeed, approximately 15 % of North American male prisoners, 7.5 % of North American female prisoners, 10 % of male forensic psychiatric patients, fewer than 3 % of psychiatric patients, and an estimated 1 % or less of the general community would have PCL-R scores of this magnitude.

The PCL-R is recognized as the “gold standard” in the assessment of psychopathy. It has been adapted to produce a screening version (Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version, PCL:SV) and a youth version (Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version, PCL:YV). The PCL-R has been found to be strongly related to re-offending and violence and is widely used in clinical practice and research in forensic settings. It has proven useful in predicting recidivism, poor treatment outcome, and as a strong predictor of violence. There are now well over 500 research articles and chapters on the PCL measures.

Despite the widespread use of the PCL-R, there has been heated scholarly debate in regard to the inclusion of the fourth facet – antisocial behavior – as a diagnostic feature of psychopathy. Cooke and Michie (2001) argued on the basis of factor analytic results that a three-factor model for psychopathy, essentially the first three facets of the PCL-R, was appropriate. They argued that the antisocial features of psychopathy were behavioral manifestations or consequences of these core features. Nonetheless, they still emphasized “the necessity of continuing to use the full PCL-R for risk assessment and other applied purposes” (p. 186). The suggestion of a three-factor model was subsequently disputed by Hare and colleagues who developed the fourfacet model in addition to the previous two-factor model. Nevertheless, the importance of antisocial behaviors as features of psychopathy continues to be vigorously debated in the literature, often in quite caustic exchanges (e.g., Hare and Neumann 2010; Skeem and Cooke 2010a, b). In any event, the PCL-R currently remains the instrument of choice for the assessment of psychopathic personality features, although other instruments are being developed.

Self-Report Measures Of Psychopathy

Some self-report measures have been developed to assess similar factors identified in the PCL-R. Although limited in their utility given the characteristics of manipulation and pathological lying associated with psychopathy, the measures have utility for research and some clinical applications that do not require a comprehensive assessment of the individual.

The Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP; Levenson et al. 1995) is a brief, 26-item measure that was designed to assess psychopathic features in subclinical samples. The Self-Report Psychopathy-II Scale (SRP-II) is a 60-item scale that was originally designed to be a self-report version of the PCL-R. In comparing the SPR-II to the PCL-R in forensic settings, Hare (1991) found that the total scores of each measure had a correlation of r ¼ .54. In recent years, the SRP-II was revised to form the SRP-III in response to criticisms regarding an excess of anxiety-related items and minimal inclusion of antisocial behavior items within the SRP-II.

The Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI; Lilienfeld and Andrews 1996) is a 187-item scale that was developed for use in noncriminal populations. The PPI was originally conceptualized as having eight lower-order factors and a total score. However, subsequent factor analyses suggested that the items formed two factors conceptually related to those on the PCL-R (Lilienfeld and Fowler 2006). A more recent version of the PPI was developed to lower the reading level, decrease cultural bias, and reduce the number of items to 154 (Lilienfeld and Windows 2005). The PPI-R is reported to perform similarly to the original measure, but additional research is warranted.

What Causes Psychopathy?

Despite the long-standing interest in psychopathy, research and knowledge pertaining to the etiology of psychopathy is in its infancy. Some evidence suggests that psychopathy has a genetic influence. Although it is difficult to know precisely how much of the psychopathic personality is attributed to genetics, it is likely to be in the order of 30 % of the variance of personality. This shows that while genetics is an important contributing factor to the etiology of psychopathy, it is not the full story.

Discussions regarding the causes of psychopathy are often tied to speculation and theories about variants or subtypes of psychopathy. Researchers have proposed that psychopathy is not a homogeneous construct, but rather a heterogeneous construct with different etiological factors associated with different subtypes of psychopathy. Most often, these subtypes are referred to as primary and secondary psychopathies (Karpman 1948; Lykken 1995). Each of these subtypes has its own hypothesized etiology and associated characteristics.

Traditionally, the primary psychopath has been described as incapable of experiencing emotions, thus not capable of feelings such as guilt, empathy, or remorse. The primary psychopath is cold and calculating and engages in behavior not hampered by anxiety. In contrast, the secondary psychopath can experience a high level of negative emotions, such as anxiety and guilt, and displays behavior that is more aggressive and impulsive.

It has been suggested that the affective deficit underlying primary psychopathy occurs as a result of nature (e.g., genetics), whereas the affective disruption of the secondary psychopath is the result of nurture (e.g., environmental insults) (Karpman 1948). Environmental factors responsible for the later development of secondary psychopathy have been suggested to include unresolved conflicts resulting from harsh punishment and parental rejection (Karpman 1948), poor and ineffective parenting (Lykken 1995), and early childhood abuse or abandonment (Porter 1996). Not only does the speculated etiology of primary versus secondary psychopathy differ, but so does expectations regarding treatment outcome for the two subtypes. Given the presence of anxiety and learned emotional adaptation to environmental abuses, the secondary psychopath is seen as more amenable to treatment than the primary psychopath (see Ogloff and Wood 2010).

Research from Skeem and colleagues (2007) also lends empirical support to distinct subtypes of psychopathy. Skeem and her colleagues (2007) found support for two homogeneous groups that parallel classic primary and secondary psychopathy formulations. They found that violent psychopaths who scored high on a measure of psychopathy were distinguishable based on their level of anxiety. Skeem and colleagues (2007) noted that “secondary (high-anxious) psychopaths were most drastically distinguished from primary (low-anxious) psychopaths by their (a) emotional disturbance (anxiety, major mental and substance abuse disorders, borderline features, impaired functioning), (b) interpersonal hostility (irritability, paranoid features, indirect aggression), and (c) interpersonal submissiveness (lack of assertiveness, withdrawal, avoidant and depend-ant features)” (p. 405).

A considerable amount of research has been devoted to the study of emotional, attentional, and cognitive processing in psychopathic personality disorder. This research shows that psychopathy is not readily interpreted in terms of damage to specific areas of the brain; but any brain abnormalities that do exist are subtle and likely more functional than structural. For example, while brain anomalies in psychopaths are largely found in the amygdala and orbital-frontal cortex, individuals with physical damage to these areas show more global deficits than do psychopaths. As such, psychopathy is not apparently the product of structural brain damage or deficits.

While structural brain differences of psychopaths compared to non-psychopaths are limited, considerable research exists to show that there are some significant functional differences in the brain functioning between psychopaths and others. Generally, the differential processing of attention and emotional information by psychopaths has implicated anomalies in the functioning of the amygdala, the orbital-frontal cortex (OFC), and differences in cerebral asymmetry. For example, the amygdala is considered to modulate sensory processing and the processing of emotional stimuli, as well as influencing goaldirected behavior, all of which appear impaired in psychopathy (Blair et al. 2005). Studies have shown impaired learning from punishment when there is potential for reward (gambling tasks), reduced autonomic response to distress in others, impaired naming of fearful and sad expressions (but not other emotions), and reduced physiological responses to anticipation of fear or pain-inducing stimuli (see Blair et al. 2005; Hiatt and Newman 2006).

Substantial advancement has been made toward understanding the neurobiological aspects of psychopathic personality, but a coherent picture or etiological model that can explain all aspects of these anomalies or how they may give rise to either the personality or behavioral characteristics of psychopathy is yet to be devised. The most widely inclusive theory is posited by Blair and colleagues (2005), who argue that genetic anomalies disrupt amygdala functioning from an early age, leading to impairment in emotional learning as a core dysfunction of psychopathy. This impaired emotional learning would not necessarily lead to the development of the full psychopathy syndrome (such as antisocial and impulsive behaviors), but increases the probability that an individual will learn to employ antisocial means to achieve goals depending on social environment and learning history (i.e., environmental risk factors). Blair and colleagues argue that instrumental aggression may result from impairment to the amygdala functioning (impaired socialization, affect processing, and empathy), while reactive aggression may be the result of OFC impairment (inability to modify behavior to achieve goals when environmental cues change, leading to frustration and then aggression). However, their theory fails to account for additional brain abnormalities in psychopathy, such as cerebral asymmetry. In addition, the heavy focus of research on male adult prison inmates (where psychopathic personality is likely to be easily available and identifiable) makes it difficult to separate deficits associated with the core personality features (Factor 1) and antisocial behavior more generally. There is a need to examine potential neurological and cognitive abnormalities among “successful” psychopaths in the community, as well as in alternative cultural, ethnic, gender, and age groups.

Criminal Correlates Of Psychopathy

As noted previously, less than one percent of people in the general population are thought to be psychopaths. However, research shows that between 15 % and 20 % of people in prisons have high scores on the PCL-R (Hare 2003). Literally hundreds of studies, and at least six meta-analyses, have explored the relationship between psychopathy and recidivism; they have uniformly found that psychopaths are at greater risk for offending and violent offending. While the specific rates of offending differ somewhat across the samples, as compared to non-psychopaths, at 1-year follow-up, psychopaths have been found to be approximately three times as likely to offend and four times as likely to violently re-offend than nonpsychopathic offenders. Indeed, Hemphill (2007) reported that across three separate metaanalyses, the unweighted correlation between PCL-R scores and violent recidivism was “in the .20–25 range” and admitted that these were conservative values (i.e., the effect sizes were larger when weighted by sample size). Furthermore, Monahan and colleagues (2001) studied a range of risk factors for violence among civil psychiatric patients in the United States and found that the PCL:SV had the highest correlation with subsequent violence of all of the 134 risk factors (r ¼ .26).

While not originally developed to be a risk assessment measure, psychopathy has emerged as a robust risk factor for criminal recidivism, and many have advocated its use in any assessment of risk for offending or violence. For example, Hart (1998) stated that “psychopathy is such a robust and important risk factor for violence that failure to consider it may constitute professional negligence” (p. 133). Accordingly, several formal risk assessment schemes require that one include or consider scores on the PCL-R or the PCL:SV.

Psychopathic offenders differ in many ways from their non-psychopathic criminal counterparts. Compared with other offenders, psychopaths are at greater risk for callous, coldblooded behavior and crimes, institutional infractions, general recidivism, violent recidivism, and sexual recidivism (Hare 2003). Psychopaths also engage in a greater number and variety of criminal behaviors when compared to other repeat offenders, begin committing crimes at an earlier age than other career criminals, and display a different pattern across the lifespan. While criminal behavior tends to decrease over time, Hare and colleagues found that only about half of the psychopaths studied demonstrated a significant decrease in criminal behaviors beginning around ages 35–40 years. However, this reduction largely applied to nonviolent offences and minimal reduction was seen in violent behavior.

Woodworth and Porter (2002) studied 125 homicide offenders and found that the majority of homicides committed by psychopaths were “instrumental” murders (i.e., cold-hearted murders that are conducted for revenge, thrill seeking, or some material gain) rather than “reactive” (i.e., in the heat of the moment without secondary gain). By contrast, the types of murders committed by non-psychopaths were fairly evenly split between instrumental and reactive. Among sexual homicides, psychopathic perpetrators exhibit significantly higher levels of gratuitous and sadistic violence than nonpsychopathic sexual homicide perpetrators (Porter et al. 2003). Overall, violence by psychopaths is more likely to be motivated by material gain, revenge, or thrill seeking (i.e., instrumental aggression) rather than momentary heightened emotional arousal (reactive aggression).That said, psychopaths are likely to engage in violence in response to both motivations, whereas nonpsychopath violent offenders typically do not engage in instrumentally motivated violence (Blair et al. 2005).

Psychopathy And Criminal Investigation

Given the prevalence of psychopathic personality features in the criminal justice system, particularly in regard to serious violent offenders, it is perhaps unsurprising that psychopathy is an important construct for behavioral scientists who provide consulting services to law enforcement agencies. Such activities are known variously as criminal investigative analysis, behavioral investigative advice, and offender profiling (Depue, ! Criminal Investigative Analysis; Rainbow, Gregory, & Alison, ! Behavioural Investigative Advice). These can involve making inferences about an unknown offender’s likely characteristics based on the behaviors exhibited during their crimes, as well as recommendations for investigative or interview strategy (Ault and Hazelwood 1995). Impulsivity and sensation seeking behavior, glibness and superficial charm, conning and manipulative offence behavior, and predation and instrumental violence may all suggest the presence of psychopathic personality features in an unknown offender (see O’Toole 2007). While far from a clinical diagnosis, such hypotheses, when viewed in conjunction with other inferences from the offender’s behavior, can assist in the development of appropriate investigative and interview strategies.

The White-Collar Psychopath

While most research on psychopathy has been conducted on criminals, it has long been speculated, therefore, that not all psychopaths engage in criminal or violent behavior resulting in imprisonment and that individuals with psychopathic personality can be found in a variety of successful trades and professions in the general community. Hare (1993) argued that psychopaths are “to be found nearly everywhere – in business, the home, the professions, the military, the arts, the entertainment industry, the news media, academe, and the blue-collar world” (p. 115). It has also been argued that certain psychopathic traits (fearlessness, dominance, superficial charm) may prove valuable in some professions such as law, politics, and leadership positions in business and the military (Lykken 1995). However, the limited research evidence has been based on anecdotal clinical descriptions, with almost no quantitative study (e.g., Babiak 2007). Cleckley’s seminal book (1941) described several case studies of people who possessed the “core” personality features observed in criminal psychopaths, but manifested those traits in ways that did not result in frequent criminal activity (or at least, arrest). Nonetheless, the case studies that have been discussed have shown that high psychopathy scores in the business world are associated with manipulation of co-workers and bosses, circumventing human resources, finance, and security systems, and fast-tracked promotion to management ranks and successful careers despite limited experience or professional dedication (Babiak 2007).

Descriptions of psychopaths in the community and business have highlighted terms such as “successful,” “sub-clinical,” and “white-collar” psychopaths, but conceptual difficulties have been raised in the differentiation between such individuals and their criminal counterparts. For example, Hall and Benning (2006) question whether the etiology of psychopathy among noncriminals is the same as for psychopathic criminals (i.e., do community psychopaths differ in degree or kind from criminal psychopaths?). Should “successful” psychopathy be viewed as dimensionally sub-clinical, as a moderated manifestation of the same level of traits, or as a separate clinical entity with different etiological development? These are questions that will be examined in future research on corporate and other community psychopaths.

Conclusions And Future Directions

Psychopathy is an important clinical diagnosis that has significant implications for the criminal justice system. Although few in number, psychopaths are more likely than others to engage in offending and are more likely than other offenders to re-offend or commit violent offences. The specific terms used to identify this group of people have varied over time – with terms such as antisocial personality disorder, sociopathy, and dissocial personality disorder being used in varying ways to conceptualize this population. As the information presented and discussed in this research paper shows, despite the longstanding interest and the burgeoning research on the topic of psychopathy, relatively little is still known about the etiology of this serious personality disorder.

With advanced knowledge of genetics and developing technology in brain imaging, it is known that a portion of the variance in the development of a psychopathic personality can be attributed to genetic factors. Similarly, research shows that functional and even some significant structural brain differences exist among people who are psychopathic that distinguish them from others; however, the differences are relatively small and are not yet diagnostic. With ongoing advances in technology and methodology, however, this area shows considerable promise for research. At present, it appears that the brain differences that do exist pertain to areas of the brain associated with affect and emotions and other areas that relate to behavioral control and impulsivity. Importantly, social development and environmental factors play a significant role in the development of psychopathic personality traits and the type of behavior that manifests. Taken together, psychopathy is best construed as a disorder that is influenced by interactions of genetic, biological, and social factors which are moderated by the environment.

Although psychopathy has been discussed in the broad population and among people who are not necessarily criminals (e.g., Cleckley 1941), the interest surrounding this disorder has been largely driven by the criminal correlates of psychopathy. As noted above, it is not surprising that people who are not influenced by society’s rules and laws, who do not have the capacity for affective features like empathy and guilt, and who do not learn from punishment have increased levels of offending and recidivism. Indeed, the prevalence of psychopathy in criminal (15–20 %) and even forensic mental health (10 %) samples is much greater than what is found in the community (less than 1 %). People with high levels of psychopathic personality features have been found to have higher rates of all types of offending and violence. The offences that psychopaths commit are more likely to be instrumental, or for secondary gain, than for other offenders. The violence that they inflict is typically more extreme and callous.

Taken together, psychopathy is an important construct for those who work in criminology and related fields. There is a large and growing body of research that has enabled an enhanced understanding of psychopathy and its correlates. At the time of writing this research paper, at least two significant developments were occurring in the field. First, the DSM-5 was in the final stages of development with the Personality Disorders Working Group having finished its work. It is anticipated that the DSM-5 will be published in May 2013 so one will need to wait to see exactly how antisocial personality disorder is defined at that time and whether the traditional personality features of psychopathy will be prominently featured. Second, a new measure of psychopathy, the Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathic Personality (Cooke et al. 2004) was being developed and validated. This instrument shows promise as a measure of psychopathy that builds upon the literature. It is designed to be comprehensive and dynamic with the ability to assess possible changes in the severity of symptoms over time. Preliminary research has indicated that the CAPP shows comparable predictive validity to the PCL:SV in regard to violent and nonviolent crime (Pedersen et al. 2010). Nonetheless, it will be some time before the research base is developed to know how effective the measure will be in identifying psychopathic personality features or whether it will be best utilized as a stand-alone measure or an adjunct to the PCL-R. It is clear, therefore, that despite the long history and research interest in psychopathy, there is still much to learn.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association (1968) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 2nd edn. Author, Washington, DC

- American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd edn. Author, Washington, DC

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn, text revision. Author, Washington, DC

- Ault RL, Hazelwood RR (1995) Indirect personality assessment. In: Hazelwood RR, Burgess AW (eds) Practical aspects of rape investigation, 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 205–218

- Babiak P (2007) From darkness into the light: psychopathy in industrial and organizational psychology. In: Herve H, Yuille JC (eds) The psychopath: theory, research, and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 411–428

- Blair J, Mitchell D, Blair K (2005) The psychopath: emotion and the brain. Blackwell, Malden

- Cleckley H (1941) The mask of sanity. St. Mosby, Louis

- Cooke DJ, Michie C (2001) Refining the construct of psychopathy: towards a hierarchical model. Psychol Assess 13:171–188

- Cooke DJ, Hart SD, Logan C, Michie C (2004) Comprehensive assessment of psychopathic Personality – Institutional Rating Scale (CAPP-IRS). Unpublished manuscript

- Falret J (1866) La folie raisonnante ou folie morale. Ann Me´d Psychol XXIV:382–396

- Hall JR, Benning SD (2006) The “successful” psychopath: adaptive and subclinical manifestations of psychopathy in the general population. In: Patrick CJ (ed) Handbook of psychopathy. Guilford, New York, pp 459–478

- Hare RD (1980) A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in clinical populations. Personal Individ Differ 1:111–119

- Hare RD (1991) The psychopathy checklist – revised. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

- Hare RD (1993) Without conscience: the disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. Guilford, New York

- Hare RD (2003) The psychopathy checklist – revised, 2nd edn. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

- Hare RD, Neumann CS (2010) The role of antisociality in the psychopathy construct: comment on Skeem and Cooke (2010). Psychol Assess 22:446–454

- Hart SD (1998) The role of psychopathy in assessing risk for violence: conceptual and methodological issues. Leg Criminol Psychol 3:121–137

- Hemphill JF (2007) The Hare psychopathy checklist and recidivism: methodological issues and guidelines for critically evaluating empirical evidence. In: Herve´ H, Yuille JC (eds) The psychopath: theory, research, and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 141–170

- Hiatt KD, Newman JP (2006) Understanding psychopathy: the cognitive side. In: Patrick CJ (ed) Handbook of psychopathy. Guilford, New York, pp 334–352

- Karpman B (1948) The myth of the psychopathic personality. Am J Psychiatry 104:523–534

- Levenson MR, Kiehl KA, Fitzpatrick CM (1995) Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. J Pers Soc Psychol 68:151–158

- Lilienfeld SO, Andrews BP (1996) Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. J Pers Assess 66:488–524

- Lilienfeld SO, Fowler KA (2006) The self-report assessment of psychopathy: problems, pitfalls, and promises. In: Patrick CJ (ed) Handbook of psychopathy. Guilford, New York, pp 107–132

- Lilienfeld SO, Windows MR (2005) Professional manual for the psychopathic personality inventory-revised: (PPI-R). Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz

- Lykken D (1995) The antisocial personalities. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

- Millon T, Simonson E, Birket-Smith M (1998) Historical conceptions of psychopathy in the United States and Europe. In: Millon T, Simonson E, Birket-Smith M, Davis RD (eds) Psychopathy: antisocial, criminal, and violent behaviour. Guilford, New York, pp 3–31

- Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Silver E, Appelbaum P, Robbins PC, Mulvey EP et al (2001) Rethinking risk assessment: the MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- O’Toole ME (2007) Psychopathy as a behavior classification system for violent and serial crime scenes. In: Herve´ H, Yuille JC (eds) The psychopath: theory, research, and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 301–325

- Ogloff JRP (2006) The psychopathy/antisocial personality disorder conundrum. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 40:519–528

- Ogloff JRP, Wood M (2010) The treatment of psychopathy: clinical nihilism or steps in the right direction. In: Malatesti L, McMillan J (eds) Responsibility and psychopathy: interfacing law, psychiatry, and philosophy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 155–181

- Pedersen L, Kunz C, Rasmussen K, Elsass P (2010) Psychopathy as a risk factor for violent recidivism: investigating the Psychopathy Checklist Screening Version (PCL:SV) and the Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathic Personality (CAPP) in a forensic psychiatric setting. Int J Forensic Mental Health 9:308–315

- Porter S (1996) Without conscience or without active conscience? the etiology of psychopathy revisited. Aggress Violent Behav 1:179–189

- Porter S, Woodworth M, Earle J, Drugge J, Boer D (2003) Characteristics of sexual homicides committed by psychopathic and nonpsychopathic offenders. Law Hum Behav 27:459–469

- Skeem JL, Cooke DJ (2010a) Is criminal behavior a central component of psychopathy? conceptual directions for resolving the debate. Psychol Assess 22:433–455

- Skeem JL, Cooke DJ (2010b) One measure does not a construct make: directions toward reinvigorating psychopathy research – reply to Hare and Neumann (2010). Psychol Assess 22:455–459

- Skeem JL, Johansson P, Andershed H, Kerr M, Eno Louden J (2007) Two subtypes of psychopathic violent offenders that parallel primary and secondary variants. J Abnorm Psychol 116:395–409

- Woodworth M, Porter S (2002) In cold blood: characteristics of criminal homicides as a function of psychopathy. J Abnorm Psychol 111:436–445

- World Health Organization (1992) International classification of diseases and related health problems (10th revision). Author, Geneva

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.