This sample Academic Interventions Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

This research paper reviews the field of academic interventions. It describes types and targets of academic interventions; intervention delivery systems; guidelines relating to the selection, implementation, and evaluation of academic interventions; and selected evidence-based strategies.

Outline

- Overview

- Types of Academic Problems

- Intervention Delivery Systems

- Guidelines for Selecting, Implementing, and Evaluating Academic Interventions

- Academic Intervention Targets

- Summary and Future Directions

1. Overview

Today’s educators are encountering increasing numbers and proportions of students who have trouble achieving at grade-level expectations. Whether these students are termed difficult to teach, learning disabled, or at risk, they fail to respond to traditional instructional methods. The need for academic interventions is underscored by reports from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) indicating that fewer than one-third of American fourth and eighth-grade students are performing at proficient levels in reading, mathematics, and writing. Recent federal legislation, including the 1997 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which promotes the use of interventions prior to referral for special education services, and the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, with its mandates for empirically validated practices, is also spurring interest in strategies that can enhance teachers’ capacity to meet students’ needs and students’ capacity to respond to instruction.

2. Types Of Academic Problems

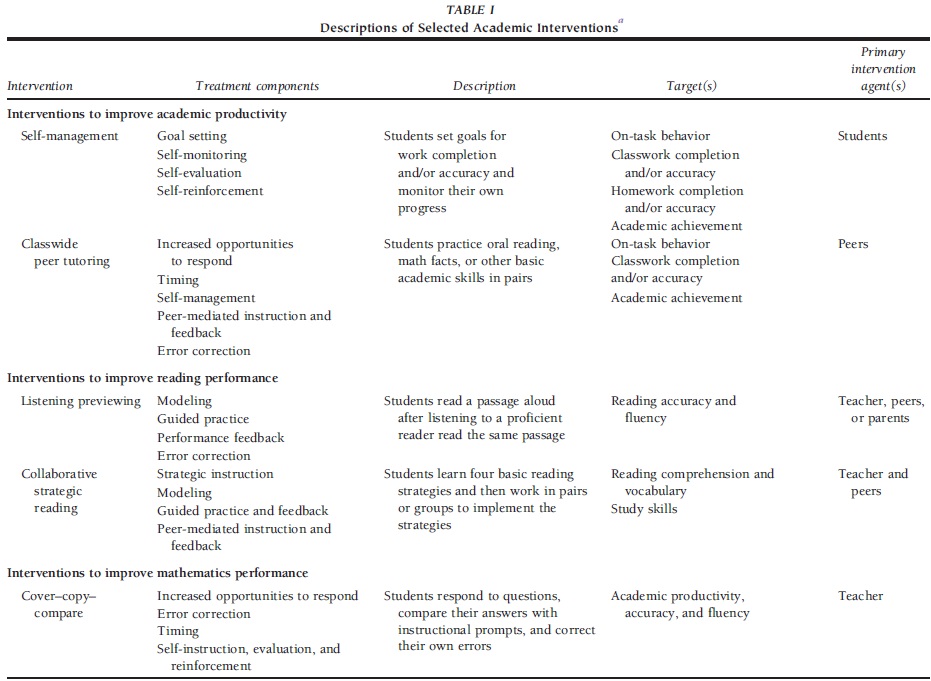

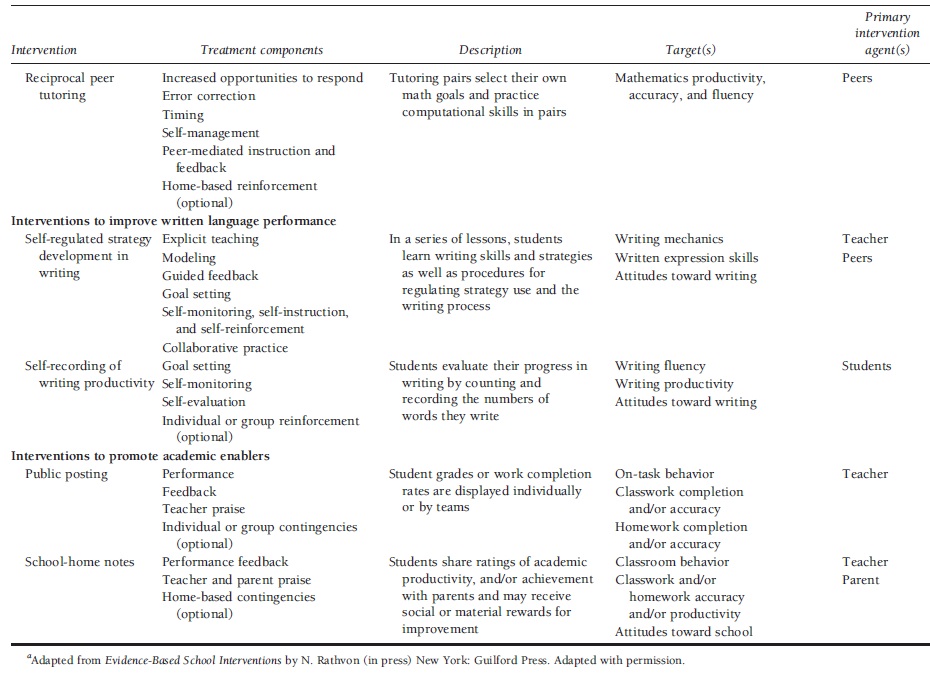

Academic problems may be characterized as skill deficits, fluency deficits, performance deficits, or some combination of these. Skill deficits refer to deficiencies reflecting inadequate mastery of previously taught academic skills. Fluency deficits refer to deficiencies in the rate at which skills are performed accurately. Students with performance deficits possess adequate skills and fluency but do not produce work of satisfactory quantity, quality, or both. Many of the interventions presented in Table I are designed to enhance skill acquisition and fluency by increasing opportunities to respond to academic material. Others target performance problems by using self-monitoring or contingency-based procedures, especially group-oriented contingencies that capitalize on peer influence to encourage academic productivity and motivation.

3. Intervention Delivery Systems

Academic interventions can be implemented through a variety of delivery systems, including (a) case-centered teacher consultation, (b) small-group or classroom centered teacher consultation, (c) staff development programs, and (d) intervention assistance programs (IAPs). For academic interventions with a home component, intervention services can be delivered through case-centered parent consultation, parent training programs, or parent participation in IAPs.

3.1. Intervention Assistance Programs

IAPs are based on a consultation model of service delivery and are designed to increase the success of difficult to-teach students in the regular classroom by providing consultative assistance to teachers. Since the 1990s, IAPs have become widespread, with the majority of states now requiring or recommending interventions prior to special education referral. Several IAP approaches based on collaborative consultative models of service delivery have been developed to meet the needs of difficult-to teach students in the regular classroom. These models fall into two general categories depending on whether special education personnel are involved. Key factors in successful implementation and maintenance of IAPs include administrative support, provision of high-quality interventions, and support of teachers during the intervention process. Although an increasing body of evidence supports the efficacy of IAPs in reducing referrals to special education and improving teachers’ attitudes toward diverse learners, relatively few studies have documented that IAPs produce measurable gains in student performance, and many of the studies reporting academic improvement suffer from methodological problems.

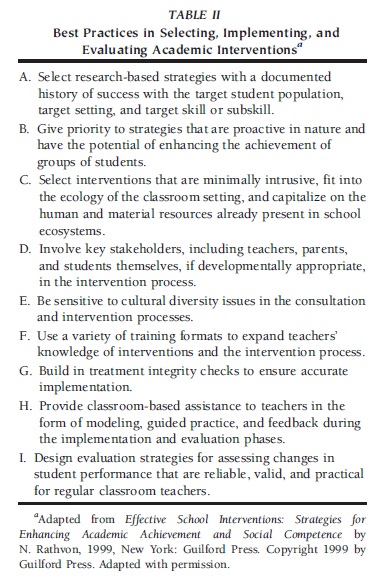

4. Guidelines For Selecting, Implementing, And Evaluating Academic Interventions

In designing interventions for students with academic problems, intervention effectiveness can be enhanced by following nine guidelines that are presented in Table II and serve as the foundation for the discussion that follows. The guidelines reflect the importance of balancing treatment efficacy with usability considerations to accommodate the realities of today’s classrooms.

4.1. Selecting Academic Interventions

Despite the growing database of evidence-based interventions, studies indicate that teachers and IAPs continue to rely on interventions characterized by familiarity or ease of implementation rather than on those with documented effectiveness. The importance of considering efficacy in intervention selection has been underscored by the Task Force on Evidence-Based Interventions in School Psychology, jointly sponsored by the Division of School Psychology of the American Psychological Association and the Society for the Study of School Psychology and endorsed by the National Association of School Psychologists. Founded in 1998 as an effort to bridge the often-cited gap between research and practice, the Task Force has developed a framework with specific efficacy criteria for evaluating empirically supported intervention and prevention programs described in the literature.

Consultants should also give priority to proactive interventions that help teachers to create learning environments that prevent academic problems from occurring by promoting on-task behavior and productivity rather than using reactive strategies that are applied after problems have already developed. Academic achievement is significantly related to the amount of time allotted for instruction and to academic engagement rates, that is, the proportion of instructional time in which students are actively engaged in learning as demonstrated by behaviors such as paying attention, working on assignments, and participating in class discussions. Although all students profit from proactive strategies that increase instructional time and academic engagement, such interventions are especially important for diverse learners, who are more likely to need additional practice on academic tasks to keep up with their grade peers.

TABLE I Descriptions of Selected Academic Interventions

TABLE I Descriptions of Selected Academic Interventions

Academic interventions should be minimally intrusive so that they can be implemented in regular classroom settings without unduly disrupting instructional and management routines. Interventions with low ecological validity (i.e., strategies that require major alterations in classroom procedures or cumbersome reinforcement delivery systems) are unlikely to become integrated into regular education routines. Priority should also be given to strategies that benefit more than one student. Traditional case-centered intervention approaches directed at a single low-performing student are of limited utility in enhancing teachers’ overall instructional effectiveness and can be very time-consuming. Group-focused strategies are both time and labor-efficient, are more acceptable to teachers and students alike, and foster a positive classroom climate by incorporating peer influence.

TABLE II Best Practices in Selecting, Implementing, and Evaluating Academic Interventions

TABLE II Best Practices in Selecting, Implementing, and Evaluating Academic Interventions

Moreover, intervention targets and procedures should be reviewed in terms of their social validity. Although many interventions target on-task behavior, increasing on-task behavior is less socially significant as an intervention goal than is enhancing rates of academic responding because increasing on-task behavior does not necessarily result in higher student achievement. Although there is little systematic research on the benefits of involving parents and students in designing interventions, input should be obtained from all stakeholders on the acceptability of proposed intervention goals and procedures.

In designing interventions, consultants must be sensitive not only to individual differences but also to differences in cultural values and norms. For example, interventions that provide concrete operant reinforcers for academic performance might be considered unacceptable by individuals from certain cultures. Unfortunately, little research to date has examined the relative efficacy and acceptability of various academic interventions with culturally and linguistically diverse learners. However, by maintaining an awareness of their own ethnocentrism and encouraging an open dialogue throughout the intervention process, consultants will be better prepared to adjust intervention services to address the needs of stakeholders from nonmainstream groups.

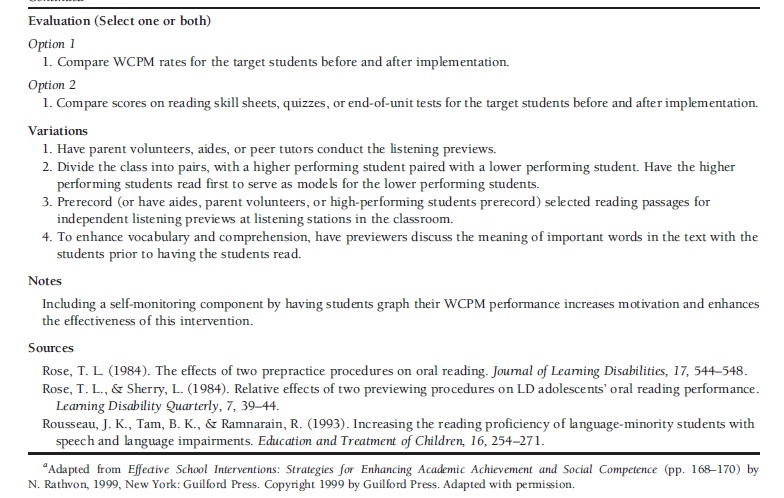

4.2. Implementing Academic Interventions

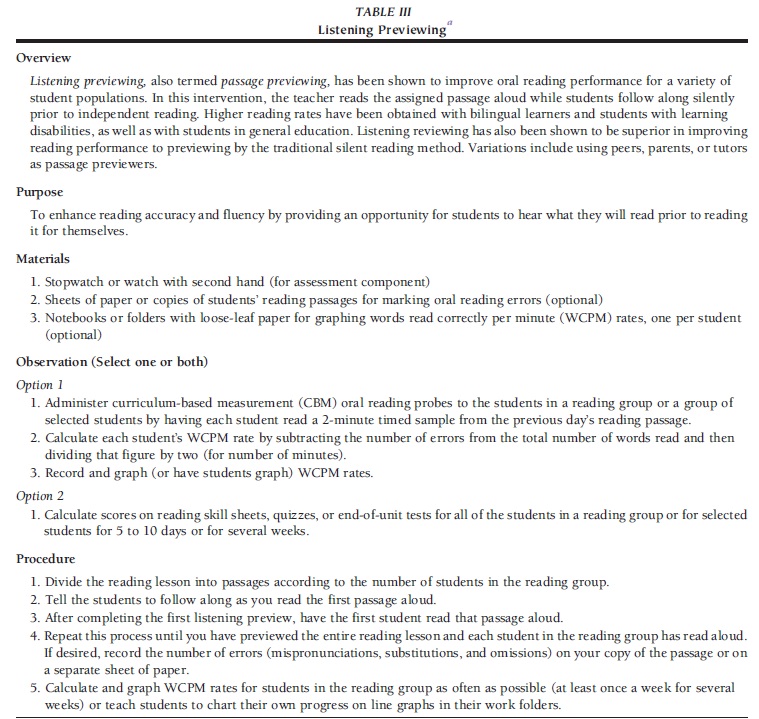

Regardless of the quality of the intervention design and the documented efficacy of the intervention components, no strategy will be effective in improving student achievement unless the teacher implements it accurately and consistently, that is, with treatment integrity. In the absence of treatment integrity measures, there is no way to determine whether changes in academic performance are due to the effects of the intervention or to factors that are unrelated to intervention components. Among the factors influencing treatment integrity are (a) intervention complexity, (b) time and material resources required for implementation, (c) the number of intervention agents, (d) efficacy (actual and as perceived by the intervention agents and stakeholders), and (e) the motivation of the intervention agents and stakeholders. Strategies for enhancing treatment integrity include (a) delivering interventions by means of a videotape or an audiotape, (b) documenting consultation contacts, (c) using an intervention manual or script, (d) having a written intervention plan, and (e) providing direct feedback to intervention agents during implementation. Table III presents an intervention script for listening previewing, a strategy targeting reading achievement. Treatment integrity can be assessed by direct observation, videotaping or audiotaping intervention sessions, or teacher-, parent-, or student-completed fidelity checklists.

TABLE III Listening Previewing

TABLE III Listening Previewing

Consultants seeking to help teachers implement classroom strategies must be prepared to provide support with many aspects of the intervention process. Although teachers must implement the strategy, studies suggest that treatment integrity and, ultimately, the success of the intervention are related to the degree to which classroom-based assistance is provided to teachers during implementation. For example, IAPs in which a designated case manager works collaboratively with the referring teacher throughout the implementation process are more likely to report measurable gains in student performance than are IAPs lacking such support systems.

4.3. Evaluating Academic Interventions

Systematically evaluating performance change not only provides information that is useful in monitoring and increasing intervention effectiveness but also contributes to teachers’ maintenance of interventions by demonstrating that positive change is occurring.

Although researchers have developed several measures for assessing teachers’ perceptions of changes in students’ academic performance, it is important to assess actual student outcomes and not merely teachers’ or parents’ perceptions of improvement. Similarly, researchers have often evaluated the effects of academic interventions in terms of task completion rates without regard for accuracy or the absolute level of achievement. Ultimately, the effectiveness of academic interventions should be evaluated in terms of meaningful changes in students’ academic achievement relative to grade-level expectations.

4.3.1. Curriculum-Based Assessment

In recent years, intervention-oriented researchers have developed alternative assessment methodologies to traditional norm-referenced tests with the goal of identifying students in need of supplementary academic services and documenting the effectiveness of school based interventions. One of these methods, curriculum based assessment (CBA), refers to a set of procedures that link assessment directly to instruction and evaluate progress using measures taken from the students’ own curricula. Among the many different CBA models, the most fully developed is curriculum-based measurement (CBM), which has become the standard for assessing changes in student performance subsequent to interventions, especially in reading. Developed by Deno, Mirkin, and colleagues at the University of Minnesota Institute for Learning Disabilities, CBM is a generic measurement system that uses brief, fluency-based measures of basic skills in reading, mathematics, spelling, and written expression. CBM is ideally suited to monitoring the progress of students receiving academic interventions because measures are brief (1–3 min), can be administered frequently, and are based on students’ own instructional materials. Procedures for conducting CBMs in reading, mathematics, spelling, and written expression can be found in Rathvon’s 1999 book.

5. Academic Intervention Targets

Academic interventions can be categorized according to targets as follows: (a) interventions designed to enhance academic productivity, including classwork, independent seatwork, and homework; (b) interventions targeting achievement in specific academic subjects; and (c) interventions targeting what DiPerna and Elliott termed academic enablers, that is, nonacademic skills, behaviors, and attitudes that contribute to academic competence. Table I describes empirically validated academic interventions from each of the three categories. The categorization is necessarily somewhat arbitrary because all of the interventions include procedures that facilitate productivity and academic enabling behaviors; however, the interventions in the academic enablers category include the largest number of behavioral and attitudinal components.

5.1. Interventions Targeting Academic Productivity

5.1.1. Self-Management

Self-management techniques involve teaching students to engage in some form of behavior, such as self-observation or self-recording, in an effort to alter a target behavior. Self-management interventions fall into one of two categories: (a) contingency-based strategies with self-reinforcement for the performance of specified tasks or (b) cognitively based strategies that use self-instruction to address academic deficits. Self-management interventions are especially appropriate for targeting academic problems because they not only enhance students’ sense of responsibility for their own behavior but also increase the likelihood that students will be able to generalize their new competencies to other situations. Many academic interventions, including most of those listed in Table I, include at least one self-management component.

5.1.2. Class wide Peer Tutoring

Increased academic responding is associated with higher levels of on-task behavior and achievement. In class wide peer tutoring, peers supervise academic responding so that every student can engage in direct skill practice during instructional periods, leaving teachers free to supervise the tutoring process. Moreover, because peer tutors are provided with the correct answers for tutoring tasks, the strategy permits immediate error correction. Of the several variations of this strategy, the best known is the Class wide Peer Tutoring (CWPT) program developed by Greenwood and colleagues at the University of Kansas to improve the achievement of entire classrooms of low-socioeconomic status urban students. CWPT has been successful in improving academic skills and productivity in a variety of domains, including oral reading, spelling, and mathematics computation, and with both regular education and special needs students.

5.2. Interventions Targeting Academic Achievement

This section discusses some of the best-known and most widely validated interventions in three academic areas: reading, mathematics, and written language.

5.2.1. Interventions to Improve Reading Performance

Reading problems are the most frequent cause of referrals to school psychologists and IAPs. Three sets of skills are required for proficient reading: (a) decoding (i.e., the process leading to word recognition), (b) comprehension (i.e., the ability to derive meaning from text), and (c) fluency (i.e., the ability to read quickly and accurately). Although reading interventions can be categorized according to their primary subskill target, interventions focusing on one subskill have the potential to improve other competencies due to the interrelated nature of the reading process. The two interventions described in this section primarily target fluency and comprehension.

5.2.1.1. Listening Previewing

Listening previewing, one of the best-known stand-alone reading interventions, promotes fluency by providing students with an effective reading model prior to the students reading aloud. Combining listening previewing with discussion of key words in the selection to be read is associated with enhanced outcomes, especially in terms of comprehension. Listening previewing ranks high in both efficacy and usability and has been implemented successfully with regular education students, bilingual students, and students with learning and behavior disorders. Additional information about listening previewing is provided in Table III.

5.2.1.2. Collaborative Strategic Reading

Collaborative strategic reading (CSR) combines instruction in comprehension strategies and study skills with collaborative peer practice. Students learn four strategies through direct instruction and teacher modeling: (a) Preview (i.e., previewing and predicting), (b) Click and Clunk (i.e., monitoring for understanding and vocabulary knowledge), (c) Get the Gist (i.e., understanding the main idea), and (d) Wrap-Up (i.e., self-questioning for understanding). After students have mastered the strategies, they implement them within cooperative groups. CSR has been successful in improving reading proficiency in regular education, multilevel, inclusive, and special education settings. Originally designed for use with expository text in content area textbooks, it can also be applied to narrative material.

5.2.2. Interventions to Improve Mathematics Performance

The 2003 NAEP report on mathematics revealed serious deficiencies in math achievement in the general student population. Although the percentage of fourth graders performing at or above the proficient level (29%) was higher in 2003 than in all previous assessment years since 1990, sizable numbers of students failed to reach even the basic level of proficiency (23%). The situation was even more dismal for eighth graders, with only 23% performing well enough to be classified as proficient. Although students with difficulties in learning mathematics constitute a very heterogeneous group, they generally exhibit deficits in one or more of three areas: (a) computational skills, including the basic operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division; (b) computational fluency, that is, speed and automaticity with math facts; and (c) mathematics applications, including areas such as money, measurement, time, and word problems. Targets of mathematics interventions can be characterized as (a) foundational arithmetic skills (e.g., number knowledge, basic understanding of mathematical operations), (b) acquisition and automatization of basic computational skills, and (c) problem-solving skills. Recent meta-analyses of mathematics interventions with low-achieving students and/or students with disabilities have reported the greatest efficacy for interventions targeting basic skills and the least efficacy for interventions focusing on higher order mathematics skills. Promising intervention components include frequent feedback to teachers and parents regarding student performance, explicit instruction in math concepts and procedures, and peer-assisted learning. The two interventions described in this section use highly structured, multicomponent approaches to enhance basic skills acquisition and fluency.

5.2.2.1. Cover–Copy–Compare

The cover–copy– compare (CCC) strategy, originally developed by Skinner and colleagues at Mississippi State University, is a self-management intervention that can be used to enhance accuracy and fluency in a variety of academic subjects. Students look at an academic stimulus (e.g., a multiplication problem for CCC mathematics), cover it, copy it, and evaluate their response by comparing it to the original stimulus. CCC combines several empirically based intervention components, including self-instruction, increased opportunities to respond to academic material, and immediate corrective feedback.

5.2.2.2. Reciprocal Peer Tutoring

Reciprocal peer tutoring (RPT) in mathematics, developed by Fantuzzo and associates at the University of Pennsylvania, combines self-management techniques and group contingencies within a peer tutoring format. Although both CWPT and RPT involve peer-mediated instruction, RPT includes self-management and subgroup contingencies, with teams of students selecting and working to obtain their own rewards. RPT has been demonstrated to enhance not only math performance but also students’ perceptions of their own scholastic competence. Including a home-based reinforcement component enhances positive outcomes.

5.2.3. Interventions to Improve Written Language Performance

Writing is a crucial skill for school success because it is a fundamental way in which to communicate ideas and demonstrate knowledge in the content areas. Unfortunately, writing problems not only are characteristic of most students with learning disabilities but also are prevalent in the general student population. According to the 2002 NAEP report on writing, only 26% of 4th graders scored at the proficient level, with the percentage dropping to 22% for 12th graders. The pervasiveness of writing problems suggests that poor writing achievement is related less to internal student disabilities than to inadequate writing instruction. During the past decade or so, research on the cognitive processes underlying writing has led to a shift in writing instruction from an emphasis on product (e.g., grammar, mechanics, content) to an emphasis on the processes used to generate written productions (e.g., brainstorming, writing multiple drafts, developing a sense of audience, incorporating feedback from others). As a result, writing interventions increasingly focus on student performance of various aspects of the writing process, including planning, sentence generation, and revising. The interventions in this section target several writing process components, including fluency and compositional elements such as planning and editing.

5.2.3.1. Self-Regulated Strategy Development in Writing

Self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) is an instructional approach that combines explicit teaching and modeling of compositional strategies with a set of self-regulation procedures. In a series of studies, Graham, Harris, and colleagues at the University of Maryland have documented that SRSD improves the quantity and quality of narrative and expository writing for students with writing disabilities as well as for normally developing writers. In addition to enhancing writing performance, SRSD is associated with improved feelings of self-efficacy and more positive attitudes toward writing for students. Most applications of SRSD include paired and/or small group learning activities at specific steps in the training process to provide additional opportunities for feedback and collaboration without direct teacher supervision.

5.2.3.2. Self-Recording of Writing Productivity

This intervention uses CBM-type methodology in the context of self-monitoring procedures to increase writing fluency. Self-recording word counts during free writing periods provides students with opportunities for positively evaluating their own writing fluency and yields useful progress monitoring data by showing teachers when changes in instruction are followed by increases in writing performance rates. Setting writing production goals and self-recording word counts produce increases in the number of words written and improvements in free writing expressiveness without a deterioration in writing mechanics, compared with untimed writing periods. Some variations include individual and group reinforcements for achieving preset goals.

5.3. Interventions to Enhance Academic Enablers

According to DiPerna and Elliott, academic success requires more than skill in performing assigned tasks. That is, although classroom instruction focuses on the acquisition of concepts, knowledge, and skills in academic subjects, students must become active participants in their educational experiences to benefit from that instruction. The two interventions in this category have been widely used as stand-alone strategies or in combination with other intervention components to facilitate achievement and productivity across a range of academic skill domains.

5.3.1. Public Posting

Public posting involves displaying some kind of classroom record (e.g., a chart) that documents student achievement or productivity. Whereas traditional public posting strategies often record incidents of negative behavior (e.g., the names of disruptive or unproductive students), public posting as an academic intervention is a positive strategy that displays student progress in achieving specified academic goals. Originally designed to encourage improvement in individual student performance, small-group and classwide versions that target group achievement and capitalize on positive peer influence have also been developed. Adding individual or group contingencies can enhance outcomes but does not appear to be critical to intervention effectiveness.

5.3.2. School–Home Notes

School–home notes encourage parental involvement in children’s classroom performance, permit a broader range of reinforcers than are generally available to teachers, and have demonstrated efficacy for both academic problems and behavior problems. School– home communications can be arrayed along a continuum of parental involvement, ranging from notes that merely provide information to notes that ask parents to deliver predetermined consequences contingent on the reported student performance. Although strategies that include home consequences can have powerful effects on student performance, establishing and maintaining an effective school–home communication system can be difficult for even a single student, much less for groups or entire classrooms of unproductive students. Not surprisingly, the majority of published school–home note interventions have targeted individual students or small groups of students, usually in special education settings.

6. Summary And Future Directions

Given the growing diversity and needs of the student population, interest in the development and empirical validation of academic interventions is likely to increase. Although the knowledge base of effective school-based interventions has increased dramatically during the past 15 years, determining which intervention components and which intervention parameters (e.g., intensity, duration, delivery system) are maximally effective for which types of students will be a continuing challenge for researchers and practitioners alike. Additional studies are especially needed to identify strategies that are high in both efficacy and usability for second-language learners and secondary school students with special needs.

References:

- Daly, E. J., & McCurdy, M. (Eds.). (2002). Developments in academic assessment and intervention [Special issue]. School Psychology Review, 31(4).

- DiPerna, C., & Elliott, S. N. (Eds.). (2002). Promoting academic enablers to improve student performance: Considerations for research and practice [Miniseries]. School Psychology Review, 31(3).

- Elliott, S. N., Busse, R. T., & Shapiro, E. S. (1999). Intervention techniques for academic performance In C. R. Reynolds, & T. B. Gutkin (Eds.), Handbook of school psychology (3rd ed., pp. 664–685). New York: John Wiley.

- Gutkin, T. B. (Ed.). (2002). Evidence-based interventions in school psychology: The state of the art and future directions [special issue]. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(4).

- Rathvon, (1996). The unmotivated child: Strategies for helping your underachiever become a successful student. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Rathvon, N. (1999). Effective school interventions: Strategies for enhancing academic achievement and social competence. New York: Guilford Press.

- Shinn, M. R., Walker, H. M., & Stoner, G. (Eds.). (2002). Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

- Swanson, H. L. (2000). What instruction works for students with learning disabilities? Summarizing the results from a meta-analysis of intervention In R. Gersten, E. P. Schiller, & S. Vaughn (Eds.), Contemporary special education research: Syntheses of the knowledge base on critical instructional issues (pp. 1–30). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Upah, R. F., & Tilly, W. D. (2002). Best practices in designing, implementing, and evaluating quality interventions. In A. Thomas, & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology IV (pp. 483–502). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.