This sample Acculturation Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Acculturation is the process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between cultural groups and their individual members. Such contact and change occur during colonization, military invasion, migration, and sojourning (e.g., tourism, international study, overseas posting). It continues after initial contact in culturally plural societies, where ethnocultural communities maintain features of their heritage cultures. Adaptation to living in culture contact settings takes place over time. Occasionally it is stressful, but often it results in some form of accommodation. Acculturation and adaptation are now reasonably well understood, permitting the development of policies and programs to promote successful outcomes for all parties.

Outline

- Acculturation Concept

- Acculturation Contexts

- Acculturation Strategies

- Acculturative Stress

- Adaptation

- Applications

1. Acculturation Concept

The initial interest in acculturation grew out of a concern for the effects of European domination of colonial and indigenous peoples. Later, it focused on how immigrants (both voluntary and involuntary) changed following their entry and settlement into receiving societies. More recently, much of the work has been involved with how ethnocultural groups relate to each other, and to change, as a result of their attempts to live together in culturally plural societies. Nowadays, all three foci are important as globalization results in ever larger trading and political relations. Indigenous national populations experience neocolonization; new waves of immigrants, sojourners, and refugees flow from these economic and political changes; and large ethnocultural populations become established in most countries.

Early views about the nature of acculturation are a useful foundation for contemporary discussion. Two formulations in particular have been widely quoted. The first, from Redfield and colleagues in a 1936 research paper, is as follows:

Acculturation comprehends those phenomena which result when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original culture patterns of either or both groups. .. . Under this definition, acculturation is to be distinguished from culture change, of which it is but one aspect, and assimilation, which is at times a phase of acculturation.

In another formulation, the Social Science Research Council in 1954 defined acculturation as

culture change that is initiated by the conjunction of two or more autonomous cultural systems. Acculturative change may be the consequence of direct cultural transmission; it may be derived from non-cultural causes, such as ecological or demographic modification induced by an impinging culture; it may be delayed, as with internal adjustments following upon the acceptance of alien traits or patterns; or it may be a reactive adaptation of traditional modes of life.

In the first formulation, acculturation is seen as one aspect of the broader concept of culture change (that which results from intercultural contact), is considered to generate change in ‘‘either or both groups,’’ and is distinguished from assimilation (which may be ‘‘at times a phase’’). These are important distinctions for psychological work and are pursued later in this research paper. In the second definition, a few extra features are added, including change that is indirect (not cultural but rather ‘‘ecological’’), is delayed (internal adjustments, presumably of both a cultural and a psychological character, take time), and can be ‘‘reactive’’ (i.e., rejecting the cultural influence and changing toward a more ‘‘traditional’’ way of life rather than inevitably toward greater similarity with the dominant culture).

In 1967, Graves introduced the concept of psychological acculturation, which refers to changes in an individual who is a participant in a culture contact situation, being influenced both by the external culture and by the changing culture of which the individual is a member. There are two reasons for keeping these two levels distinct. The first is that in cross-cultural psychology, we view individual human behavior as interacting with the cultural context within which it occurs; hence, separate conceptions and measurements are required at the two levels. The second is that not every individual enters into, and participates in, a culture in the same way, nor does every individual change in the same way; there are vast individual differences in psychological acculturation, even among individuals who live in the same acculturative arena.

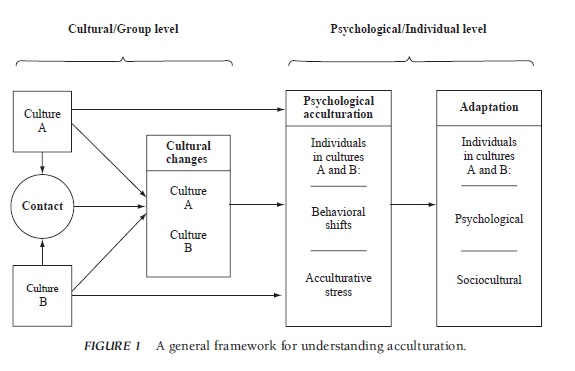

A framework that outlines and links cultural and psychological acculturation and identifies the two (or more) groups in contact is presented in Fig. 1. This framework serves as a map of those phenomena that the author believes need to be conceptualized and measured during acculturation research. At the cultural level (on the left of the figure), we need to understand key features of the two original cultural groups (A and B) prior to their major contact, the nature of their contact relationships, and the resulting dynamic cultural changes in both groups, and in the emergent ethnocultural groups, during the process of acculturation. The gathering of this information requires extensive ethnographic, community-level work. These changes can be minor or substantial and can range from being easily accomplished to being a source of major cultural disruption. At the individual level (on the right of the figure), we need to consider the psychological changes that individuals in all groups undergo and their eventual adaptation to their new situations. Identifying these changes requires sampling a population and studying individuals who are variably involved in the process of acculturation. These changes can be a set of rather easily accomplished behavioral shifts (e.g., in ways of speaking, dressing, or eating; in one’s cultural identity), or they can be more problematic, producing acculturative stress as manifested by uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Adaptations can be primarily internal or psychological (e.g., sense of well-being or self-esteem) or sociocultural, linking the individual to others in the new society as manifested, for example, in competence in the activities of daily intercultural living.

FIGURE 1 A general framework for understanding acculturation.

FIGURE 1 A general framework for understanding acculturation.

2. Acculturation Contexts

As for all cross-cultural psychology, it is imperative that we base our work on acculturation by examining its cultural contexts. We need to understand, in ethnographic terms, both cultures that are in contact if we are to understand the individuals that are in contact.

In Fig. 1, we saw that there are five aspects of cultural contexts: the two original cultures (A and B), the two changing ethnocultural groups (A and B), and the nature of their contact and interactions.

Taking the immigration process as an example, we may refer to the society of origin (A), the society of settlement (B), and their respective changing cultural features following contact (A1 and B1). A complete understanding of acculturation would need to start with a fairly comprehensive examination of the societal contexts. In the society of origin, the cultural characteristics that accompany individuals into the acculturation process need description, in part to understand (literally) where the person is coming from and in part to establish cultural features for comparison with the society of settlement as a basis for estimating an important factor to be discussed later: cultural distance. The combination of political, economic, and demographic conditions being faced by individuals in their society of origin also needs to be studied as a basis for understanding the degree of voluntariness in the migration motivation of acculturating individuals. Arguments by Richmond in 1993 suggested that migrants can be arranged on a continuum between reactive and proactive, with the former being motivated by factors that are constraining or exclusionary (and generally negative in character), and the latter being motivated by factors that are facilitating or enabling (and generally positive in character). These contrasting factors were also referred to as push/ pull factors in the earlier literature on migration motivation.

In the society of settlement, a number of factors have importance. First, there are the general orientations that a society and its citizens have toward immigration and pluralism. Some societies have been built by immigration over the centuries, and this process may be a continuing one, guided by a deliberate immigration policy. The important issue to understand for the process of acculturation is both the historical and attitudinal situations faced by migrants in the society of settlement. Some societies are accepting of cultural pluralism resulting from immigration, taking steps to support the continuation of cultural diversity as a shared communal resource. This position represents a positive multicultural ideology and corresponds to the integration strategy. Other societies seek to eliminate diversity through policies and programs of assimilation, whereas still others attempt to segregate or marginalize diverse populations in their societies. Murphy argued in 1965 that societies that are supportive of cultural pluralism (i.e., with a positive multicultural ideology) provide a more positive settlement context for two reasons. First, they are less likely to enforce cultural change (assimilation) or exclusion (segregation and marginalization) on immigrants. Second, they are more likely to provide social support both from the institutions of the larger society (e.g., culturally sensitive health care, multicultural curricula in schools) and from the continuing and evolving ethnocultural communities that usually make up pluralistic societies. However, even where pluralism is accepted, there are well-known variations in the relative acceptance of specific cultural, ‘‘racial,’’ and religious groups. Those groups that are less well accepted experience hostility, rejection, and discrimination, one factor that is predictive of poor long-term adaptation.

3. Acculturation Strategies

Not all groups and individuals undergo acculturation in the same way; there are large variations in how people seek to engage the process. These variations have been termed acculturation strategies. Which strategies are used depends on a variety of antecedent factors (both cultural and psychological), and there are variable consequences (again both cultural and psychological) of these different strategies. These strategies consist of two (usually related) components: attitudes and behaviors (i.e., the preferences and actual outcomes) that are exhibited in day-to-day intercultural encounters.

The centrality of the concept of acculturation strategies can be illustrated by reference to each of the components included in Fig. 1. At the cultural level, the two groups in contact (whether dominant or nondominant) usually have some notion about what they are attempting to do (e.g., colonial policies, motivations for migration), or of what is being done to them, during the contact. Similarly, the elements of culture that will change depend on the group’s acculturation strategies. At the individual level, both the behavior changes and acculturative stress phenomena are now known to be a function, at least to some extent, of what people try to do during their acculturation, and the longer term outcomes (both psychological and sociocultural adaptations) often correspond to the strategic goals set by the groups of which they are members.

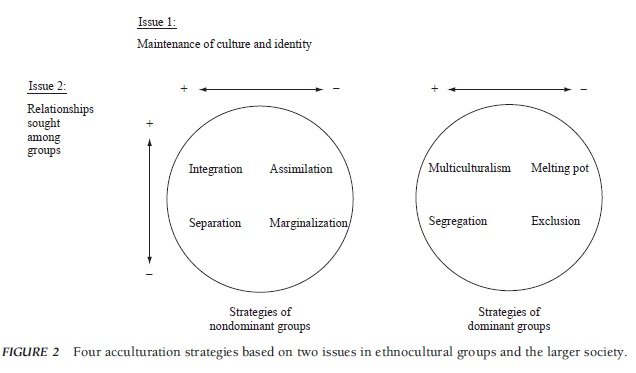

Four acculturation strategies have been derived from two basic issues facing all acculturating peoples. These issues are based on the distinction between orientations toward one’s own group and those toward other groups. This distinction is rendered as a relative preference for maintaining one’s heritage culture and identity and as a relative preference for having contact with and participating in the larger society along with other ethnocultural groups. This formulation is presented in Fig. 2.

These two issues can be responded to on attitudinal dimensions, represented by bipolar arrows. For purposes of presentation, generally positive or negative orientations to these issues intersect to define four acculturation strategies. These strategies carry different names, depending on which ethnocultural group (the dominant or nondominant one) is being considered. From the point of view of nondominant groups (on the left of Fig. 2), when individuals do not wish to maintain their cultural identity and instead seek daily interaction with other cultures, the assimilation strategy is defined. In contrast, when individuals place a value on holding onto their original culture while wishing to avoid interaction with others, the separation alternative is defined. When individuals have an interest in maintaining their original culture while in daily interactions with other groups, integration is the option. In this case, they maintain some degree of cultural integrity while seeking, as members of an ethnocultural group, to participate as an integral part of the larger social network. Finally, when individuals have little possibility of, or interest in, cultural maintenance (often for reasons of enforced cultural loss) and little interest in having relations with others (often for reasons of exclusion or discrimination), marginalization is defined.

This presentation was based on the assumption that nondominant groups and their individual members have the freedom to choose how they want to acculturate. This, of course, is not always the case. When the dominant group enforces certain forms of acculturation or constrains the choices of nondominant groups or individuals, other terms need to be used.

FIGURE 2 Four acculturation strategies based on two issues in ethnocultural groups and the larger society.

FIGURE 2 Four acculturation strategies based on two issues in ethnocultural groups and the larger society.

Integration can be ‘‘freely’’ chosen and successfully pursued by nondominant groups only when the dominant society is open and inclusive in its orientation toward cultural diversity. Thus, a mutual accommodation is required for integration to be attained and involves the acceptance by both groups of the right of all groups to live as culturally different peoples. This strategy requires nondominant groups to adopt the basic values of the larger society, whereas the dominant group must be prepared to adapt national institutions (e.g., education, health, labor) to better meet the needs of all groups now living together in the plural society.

These two basic issues were initially approached from the point of view of the nondominant ethnocultural groups. However, the original anthropological definition clearly established that both groups in contact would become acculturated. Hence, a third dimension was added: the powerful role played by the dominant group in influencing the way in which mutual acculturation would take place. The addition of this third dimension produces the right side of Fig. 2. Assimilation, when sought by the dominant group, is termed the ‘‘melting pot’’; however, when it is demanded by the dominant group, it is called the ‘‘pressure cooker.’’ When separation is forced by the dominant group, it is ‘‘segregation.’’ Marginalization, when imposed by the dominant group, is termed ‘‘exclusion.’’ Finally, integration, when diversity is a feature of the society as a whole (including all of the various ethnocultural groups), is called ‘‘multiculturalism.’’ With the use of this framework, comparisons can be made between individuals and their groups and between nondominant peoples and the larger society within which they are acculturating. The ideologies and policies of the dominant group constitute an important element of ethnic relations research, whereas the preferences of nondominant peoples are a core feature in acculturation research. Inconsistencies and conflicts among these various acculturation preferences are sources of difficulty for acculturating individuals. In general, when acculturation experiences cause problems for acculturating individuals, we observe the phenomenon of acculturative stress.

4. Acculturative Stress

Three ways in which to conceptualize outcomes of acculturation have been proposed in the literature. In the first (behavioral shifts), we observe those changes in an individual’s behavioral repertoire that take place rather easily and are usually nonproblematic. This process encompasses three subprocesses: culture shedding; culture learning; and culture conflict. The first two involve the selective, accidental, or deliberate loss of behaviors and their replacement by behaviors that allow the individual a better ‘‘fit’’ with the society of settlement. Most often, this process has been termed ‘‘adjustment’’ because virtually all of the adaptive changes take place in the acculturating individual, with few changes occurring among members of the larger society. These adjustments are typically made with minimal difficulty, in keeping with the appraisal of the acculturation experiences as nonproblematic. However, some degree of conflict may occur, and this is usually resolved by the acculturating person yielding to the behavioral norms of the dominant group. In this case, assimilation is the most likely outcome.

When greater levels of conflict are experienced and the experiences are judged to be problematic but controllable and surmountable, the second approach (acculturative stress) is the appropriate conceptualization. In this case, individuals understand that they are facing problems resulting from intercultural contact that cannot be dealt with easily or quickly by simply adjusting or assimilating to them. Drawing on the broader stress and adaptation paradigms, this approach advocates the study of the process of how individuals deal with acculturative problems on first encountering them and over time. In this sense, acculturative stress is a stress reaction in response to life events that are rooted in the experience of acculturation.

A third approach (psychopathology) has had long use in clinical psychology and psychiatry. In this view, acculturation is nearly always seen as problematic; individuals usually require assistance to deal with virtually insurmountable stressors in their lives. However, contemporary evidence shows that most people deal with stressors and reestablish their lives rather well, with health, psychological, and social outcomes that approximate those of individuals in the larger society. Instead of using the term ‘‘culture shock’’ to encompass these three approaches, the author prefers to use the term ‘‘acculturative stress’’ for two reasons. First, the notion of shock carries only negative connotations, whereas stress can vary from positive (eustress) to negative (dis-stress) in valence. Because acculturation has both positive (e.g., new opportunities) and negative (e.g., discrimination) aspects, the stress conceptualization better matches the range of affect experienced during acculturation. Moreover, shock has no cultural or psychological theory or research context associated with it, whereas stress (as noted previously) has a place in a well-developed theoretical matrix (i.e., stress–coping–adaptation). Second, the phenomena of interest have their life in the intersection of two cultures; they are intercultural, rather than cultural, in their origin. The term ‘‘culture’’ implies that only one culture is involved, whereas the term ‘‘acculturation’’ draws our attention to the fact that two cultures are interacting with, and producing, the phenomena. Hence, for both reasons, the author prefers the notion of acculturative stress to that of culture shock.

Relating these three approaches to acculturation strategies, some consistent empirical findings allow the following generalizations. For behavioral shifts, the fewest behavioral changes result from the separation strategy, whereas most result from the assimilation strategy. Integration involves the selective adoption of new behaviors from the larger society and retention of valued features of one’s heritage culture. Marginalization is often associated with major heritage culture loss and the appearance of a number of dysfunctional and deviant behaviors (e.g., delinquency, substance abuse, familial abuse). For acculturative stress, there is a clear picture that the pursuit of integration is least stressful (at least where it is accommodated by the larger society), whereas marginalization is the most stressful. In between are the assimilation and separation strategies, with sometimes one and sometimes the other being the less stressful. This pattern of findings holds for various indicators of mental health.

5. Adaptation

As a result of attempts to cope with these acculturation changes, some long-term adaptations may be achieved. As mentioned earlier, adaptation refers to the relatively stable changes that take place in an individual or group in response to external demands. Moreover, adaptation may or may not improve the fit between individuals and their environments. Thus, it is not a term that necessarily implies that individuals or groups change to become more like their environments (i.e., adjustment by way of assimilation), but it may involve resistance and attempts to change their environments or to move away from them altogether (i.e., by separation). In this use, adaptation is an outcome that may or may not be positive in valence (i.e., meaning only well adapted). This bipolar sense of the concept of adaptation is used in the framework in Fig. 1 where long-term adaptation to acculturation is highly variable, ranging from well adapted to poorly adapted and varying from a situation where individuals can manage their new lives very well to one where they are unable to carry on in the new society.

Adaptation is also multifaceted. The initial distinction between psychological and sociocultural adaptation was proposed and validated by Ward in 1996. Psychological adaptation largely involves one’s psychological and physical well-being, whereas sociocultural adaptation refers to how well an acculturating individual is able to manage daily life in the new cultural context. Although conceptually distinct, the two measures are empirically related to some extent (correlations between them are in the +.40 to +.50 range). However, they are also empirically distinct in the sense that they usually have different time courses and different experiential predictors. Psychological problems often increase soon after contact, followed by a general (but variable) decrease over time. However, sociocultural adaptation typically has a linear improvement with time. Analyses of the factors affecting adaptation reveal a generally consistent pattern. Good psychological adaptation is predicted by personality variables, life change events, and social support, whereas good sociocultural adaptation is predicted by cultural knowledge, degree of contact, and positive intergroup attitudes.

Research relating adaptation to acculturation strategies allows for some further generalizations. For all three forms of adaptation, those who pursue and accomplish integration appear to be better adapted, whereas those who are marginalized are least well adapted. And again, the assimilation and separation strategies are associated with intermediate adaptation outcomes. Although there are occasional variations on this pattern, it is remarkably consistent and parallels the generalization regarding acculturative stress.

6. Applications

There is now widespread evidence that most people who have experienced acculturation actually do survive. They are not destroyed or substantially diminished by it; rather, they find opportunities and achieve their goals, sometimes beyond their initial imaginings. The tendency to ‘‘pathologize’’ the acculturation process and outcomes may be due partly to the history of its study in psychiatry and in clinical psychology. Second, researchers often presume to know what acculturating individuals want and impose their own ideologies or personal views rather than informing themselves about culturally rooted individual preferences and differences. One key concept (but certainly not the only one) in understanding this variability, acculturation strategies, has been emphasized in this research paper.

The generalizations that have been made in this research paper on the basis of a wide range of empirical findings allow us to propose that public policies and programs that seek to reduce acculturative stress and to improve intercultural relationships should emphasize the integration approach to acculturation. This is equally true of national policies, institutional arrangements, and the goals of ethnocultural groups. It is also true of individuals in the larger society as well as members of nondominant acculturating groups.

In some countries, the integrationist perspective has become legislated in policies of multiculturalism that encourage and support the maintenance of valued features of all cultures while supporting full participation of all ethnocultural groups in the evolving institutions of the larger society. What seems certain is that cultural diversity and the resultant acculturation are here to stay in all countries. Finding a way in which to accommodate each other poses a challenge and an opportunity to social and cross-cultural psychologists everywhere. Diversity is a fact of contemporary life. Whether it is the ‘‘spice of life’’ or the main ‘‘irritant’’ is probably the central question that confronts us all—citizens and social scientists alike.

References:

- Berry, W. (1976). Human ecology and cognitive style: Comparative studies in cultural and psychological adaptation. New York: Russell Sage/Halsted.

- Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In A. Padilla (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models, and findings (pp. 9–25). Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46, 5–68.

- Berry, J. W., Kalin, R., & Taylor, D. (1977). Multiculturalism and ethnic attitudes in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Supply & Services.

- Berry, J. W., & Kim, U. (1988). Acculturation and mental health. In P. Dasen, J. W. Berry, & Sartorius (Eds.), Health and cross-cultural psychology (pp. 207–236). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Berry, J. W., Kim, U., Minde, T., & Mok, D. (1987). Comparative studies of acculturative International Migration Review, 21, 491–511.

- Berry, J. W., Kim, U., Power, S., Young, M., & Bujaki, M. (1989). Acculturation attitudes in plural societies. Applied Psychology, 38, 185–206.

- Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Graves, T. (1967). Psychological acculturation in a tri-ethnic community. South-Western Journal of Anthropology, 23, 337–350.

- Murphy, H. B. M. (1965). Migration and the major mental disorders. In M. B. Kantor (Ed.), Mobility and mental health (pp. 221–249). Springfield, IL: Thomas.

- Ogbu, U. (1992). Understanding cultural diversity and learning. Educational Researcher, 21, 5–14.

- Redfield, , Linton, R., & Herskovits, M. (1936). Memorandum on the study of acculturation. American Anthropologist, 38, 149–152.

- Richmond, (1993). Reactive migration: Sociological perspectives on refugee movements. Journal of Refugee Studies, 6, 7–24.

- Social Science Research Council. (1954). Acculturation: An exploratory American Anthropologist, 56, 973–1002.

- Ward, C. (1996). In D. Landis, & R. Bhagat (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (2nd ed., pp. 124–147). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Funham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock. London: Routledge.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.