This sample Prevention of Achievement Tests Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Achievement tests are used in diverse contexts to measure the degree to which examinees can demonstrate acquisition of knowledge or skills deemed to be important. The contexts range from teacher-made testing in elementary and secondary school settings to high-stakes testing for college admission, licensure to practice a profession, or certification. The design of achievement tests varies depending on whether the inference intended to be drawn regarding examinees’ performance is the absolute or relative level of mastery of specific knowledge and skills.

Outline

- Introduction

- Definitions and Examples

- Types of Achievement Tests

- Achievement Test Construction

- Evaluating Achievement Tests

1. Introduction

Achievement testing is a general term used to describe any measurement process or instrument whose purpose is to estimate an examinee’s degree of attainment of specified knowledge or skills. Beyond that central purpose, achievement tests differ according to their specific intended inference. Common inferences include either absolute level of performance on the specified content or relative standing vis-a` -vis other examinees on the same content. Achievement tests may be group or individually administered. They may consist of differing formats, including multiple-choice items, essays, performance tasks, and portfolios.

Achievement tests are administered in diverse contexts. For example, they are used when the school related skills of preschool pupils are measured to assess their readiness for kindergarten. During the K–12 school years, students typically take a variety of achievement tests, ranging from teacher-made informal assessments, to commercially prepared achievement batteries, to state-mandated high school graduation tests. Following formal schooling, achievement tests are administered to assess whether examinees have an acceptable level of knowledge or skill for safe and competent practice in a regulated profession for which licensure is required. In other situations, professional organizations establish certification procedures, often including an achievement test, to determine examinees’ eligibility to attain a credential or certification of advanced status in a field. Even the ubiquitous requirements to obtain a driver’s license involve an achievement testing component.

Although the purposes and contexts may vary, fairly uniform procedures are implemented for developing achievement tests and for evaluating their technical quality. Several sources exist for potential users of achievement tests to ascertain the quality of a particular test and its suitability for their purposes.

In any context where an achievement test is used, consequences for individual persons or groups may follow from test performance. In addition, the context and extent of achievement testing may have broad and sometimes unforeseen consequences affecting, for example, the security of tests, the formats used for testing, and the relationship between testing and instruction.

2. Definitions And Examples

Achievement testing refers to any procedure or instrument that is used to measure an examinee’s attainment of knowledge or skills. Achievement testing can be done informally, as in when a teacher asks a student to perform a skill such as reading aloud or demonstrating correct laboratory technique. More formal, and perhaps more common, achievement tests are routinely administered in educational and occupational settings. Examples of formal achievement testing in education would include spelling tests, chemistry lab reports, end-of-unit tests, homework assignments, and so on.

More formal achievement testing is evident in large-scale, commercially available standardized instruments. The majority of these achievement tests would be referred to as standardized to the extent that the publishers of the instruments develop, administer, and score the tests under uniform, controlled conditions. It is important to note, however, that the term ‘‘standardized’’ is (a) unrelated to test format (although the multiple-choice format is often used for standardized tests, any format may be included) and (b) not synonymous with norm referenced (although sometimes the term ‘‘standardized’’ is used to indicate that a test has norms).

Examples of standardized achievement tests used in K–12 education would include the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills, the 10th edition of the Stanford Achievement Test, and the TerraNova. These tests ordinarily consist of several subtests, measuring achievement in specific narrow areas such as language arts, mathematics, science, and study skills. The composite index formed from these subtests (often referred to as a ‘‘complete battery score’’) provides a more global measure of academic achievement.

The preceding tests are also usually administered in a group setting, although individually administered achievement tests are also available and are designed for administration in a one-on-one setting with individual students, usually of very young age. Examples of individually administered achievement tests include the Woodcock–Johnson III Tests of Achievement, the third edition of the Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning, and the Brigance Comprehensive Inventory of Basic Skills.

Following secondary schooling, achievement testing continues in colleges and universities, primarily in the form of classroom achievement measures, but would also include standardized in-training examinations and board examinations for persons pursuing professional careers. Achievement testing has a long history in diverse occupational fields. Achievement tests are routinely administered to ascertain levels of knowledge or skills when screening or selecting applicants for positions in business and industry. These tests have traditionally been administered in paper-and-pencil format, although technology has enabled administration via computer or over the Internet to be secure, fast, and accessible. For example, one vendor of computerized achievement tests offers computerized ‘‘work sample’’ achievement tests to assist human resources personnel in selecting applicants for positions in legal offices, food service, information technology, accounting, medical offices, and others. Many state, federal, and private organizations also provide achievement tests for a variety fields in which licensure or certification is required.

3. Types Of Achievement Tests

In the previous section, it was noted that achievement tests could be categorized according to administration (group or individual) and scale (informal classroom tests or more formal commercially available tests). Another more important distinction focuses on the intended purpose, use, or inference that is to be made from the observed test score.

Less formal classroom achievement tests are usually developed by a teacher to align with an instructional unit, or they may be pre-prepared by publishers of classroom textbooks or related materials. The primary purposes of such tests are for educators’ use in refining instruction and assigning grades as well as for both teacher and pupil use in understanding and responding to individual students’ strengths and weaknesses.

More formal standardized achievement tests can also be categorized according to the inferences they yield. Three such types of tests—criterion-referenced tests (CRTs), standards-referenced tests (SRTs), and normreferenced tests (NRTs)—are described in this section.

CRTs are designed to measure absolute achievement of fixed objectives comprising a domain of interest. The content of CRTs is narrow, highly specific, and tightly linked to the specific objectives. Importantly, a criterion for judging success on a CRT is specified a priori, and performance is usually reported in terms of pass/fail, number of objectives mastered, or similar terms. Thus, an examinee’s performance or score on a CRT is interpreted with reference to the criterion. The written driver’s license test is a familiar example of a CRT.

SRTs are similar to CRTs in that they are designed to measure an examinee’s absolute level of achievement vis-a` -vis fixed outcomes. These outcomes are narrowly defined and are referred to as content standards. Unlike CRTs, however, interpretation of examinees’ performance is referenced not to a single criterion but rather to descriptions of multiple levels of achievement called performance standards that illustrate what performance at the various levels means. Typical reporting methods for SRTs would consist of performance standard categories such as basic, proficient, and advanced or beginner, novice, intermediate, and expert levels. Familiar examples of SRTs include state-mandated testing for K–12 students in English language arts, mathematics, and so on to the extent that the tests are aligned with the state’s content standards in those subjects. At the national level, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is administered at regular intervals to samples of students across the United States.

NRTs are designed to measure achievement in a relative sense. Although NRTs are also constructed based on a fixed set of objectives, the domain covered by an NRT is usually broader than that covered by a CRT. The important distinction of NRTs is that examinee performance is reported with respect to the performance of one or more comparison groups of other examinees. These comparison groups are called norm groups. Tables showing the correspondence between a student’s performance and the norm group’s performance are called norms. Thus, an examinee’s performance or score on an NRT is interpreted with reference to the norms. Typical reporting methods for NRTs include z scores, percentile ranks, normal curve equivalent scores, grade or age-equivalent scores, stanines, and other derived scale scores. Familiar examples of NRTs include the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills (ITBS), the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT), and the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE).

Many publishers of large-scale achievement tests for school students also provide companion ability tests to be administered in conjunction with the achievement batteries. The tests are administered in tandem to derive ability/achievement comparisons that describe the extent to which a student is ‘‘underachieving’’ or ‘‘overachieving’’ in school given his or her measured potential. Examples of these test pairings include the Otis–Lennon School Abilities Test (administered with the Stanford Achievement Test) and the Cognitive Abilities Test (administered with the ITBS).

4. Achievement Test Construction

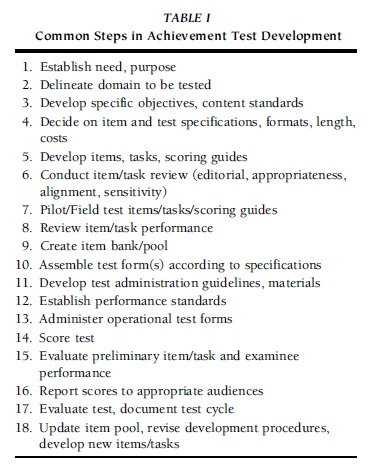

Rigorous achievement test development consists of numerous common steps. Achievement test construction differs slightly based on whether the focus of the assessment is classroom use or larger scale. Table I provides a sequence listing 18 steps that would be common to most achievement test development.

In both large and smaller contexts, the test maker would begin with specification of a clear purpose for the test or battery and a careful delineation of the domain to be sampled. Following this, the specific standards or objectives to be tested are developed. If it is a classroom achievement test, the objectives may be derived from a textbook, an instructional unit, a school district curriculum guide, content standards, or another source. Larger scale achievement tests (e.g., state mandated, standards referenced) would begin the test development process with reference to adopted state content standards. Standardized norm referenced instruments would ordinarily be based on large-scale curriculum reviews, based on analysis of content standards adopted in various states, or promulgated by content area professional associations. Licensure, certification, or other credentialing tests would seek a foundation in job analysis or survey of practitioners in the particular occupation. Regardless of the context, these first steps involving grounding of the test in content standards, curriculum, or professional practice provide an important foundation for the validity of eventual test score interpretations.

TABLE I Common Steps in Achievement Test Development

TABLE I Common Steps in Achievement Test Development

Common next steps would include deciding on and developing appropriate items or tasks and related scoring guides to be field tested prior to actual administration of the test. At this stage, test developers pay particular attention to characteristics of items and tasks (e.g., clarity, discriminating power, amenability to dependable scoring) that will promote reliability of eventual scores obtained by examinees on the operational test.

Following item/task tryout in field testing, a database of acceptable items or tasks, called an item bank or item pool, would be created. From this pool, operational test forms would be drawn to match previously decided test specifications. Additional steps would be required, depending on whether the test is to be administered via paper-and-pencil format or computer. Ancillary materials, such as administrator guides and examinee information materials, would also be produced and distributed in advance of test administration. Following test administration, an evaluation of testing procedures and test item/task performance would be conducted. If obtaining scores on the current test form that were comparable to scores from a previous test administration is required, then statistical procedures for equating the two test forms would take place. Once quality assurance procedures have ensured accuracy of test results, scores for examinees would be reported to individual test takers and other groups as appropriate. Finally, documentation of the entire process would be gathered and refinements would be made prior to cycling back through the steps to develop subsequent test forms (Steps 5–18).

5. Evaluating Achievement Tests

In some contexts, a specific achievement test may be required for use (e.g., state-mandated SRTs). However, in many other contexts, potential users of an achievement test may have a large number of options from which to choose. In such cases, users should be aware of the aids that exist to assist them in making informed choices.

One source of information about achievement tests is the various test publishers. Many publishers have online information available to help users gain a better understanding of the purposes, audiences, and uses of their products. Often, online information is somewhat limited and rather nontechnical. However, in addition to providing online information, many publishers will provide samples of test materials and technical documentation on request to potential users. Frequently, publishers will provide one set of these packets of information, called specimen sets, at no charge for evaluation purposes.

When evaluating an achievement test, it is important to examine many aspects. A number of authorities have provided advice on how to conduct such a review. For example, one textbook for school counselors by Whiston contains a section titled ‘‘Selection of an Assessment Instrument’’ that consists of several pages of advice and a user-friendly checklist. The single authoritative source for such information would likely be the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, jointly sponsored by the American Educational Research Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education.

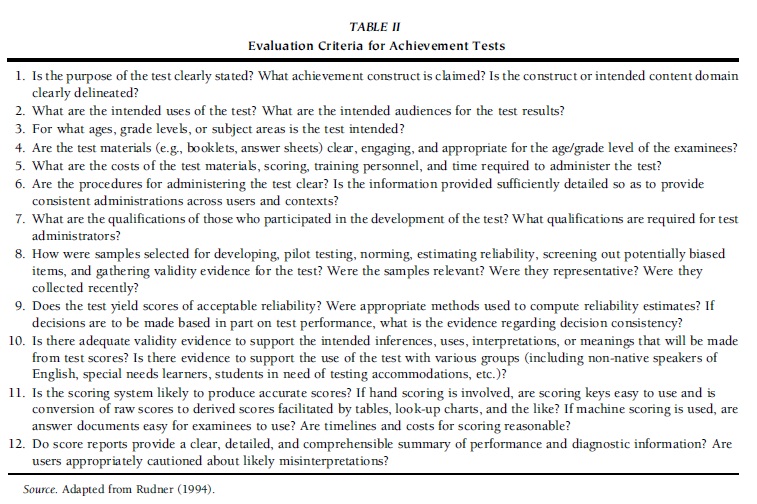

Finally, a particularly useful framework for evaluating achievement tests was developed by Rudner in 1994. Table II provides a modified version of key points identified by Rudner that should be addressed when choosing an achievement test.

It is likely that some potential users will not have the time or technical expertise necessary to fully evaluate an achievement test independently. A rich source of information exists for such users in the form of published reviews of tests. Two compilations of test reviews are noteworthy: Mental Measurements Yearbook (MMY) and Tests in Print. These references are available in nearly all academic libraries. In the case of MMY, the editors of these volumes routinely gather test materials and forward those materials to two independent reviewers. The reviewers provide brief (two to four-page) summaries of the purpose, technical qualities, and administration notes for the test. Along with the summaries, each entry in MMY contains the publication date for the test, information on how to contact the publisher, and cost information for purchasing the test. In these volumes, users can compare several options for an intended use in a relatively short time.

TABLE II Evaluation Criteria for Achievement Tests

TABLE II Evaluation Criteria for Achievement Tests

A fee-based search capability for locating test reviews is available at the MMY Web site (www.unl.edu).

References:

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. (1999). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: Author.

- Brigance, A. H., & Glascoe, F. P. (1999). Brigance Comprehensive Inventory of Basic Skills (rev. ). North Billerica, MA: Curriculum Associates.

- Cizek, G. J. (1997). Learning, achievement, and assessment: Constructs at a crossroads. In G. D. Phye (Ed.), Handbook of classroom assessment (pp. 1–32). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Cizek, G. J. (2003). Detecting and preventing classroom cheating: Promoting integrity in schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- CTB/McGraw–Hill. (1997). TerraNova. Monterey, CA: Author. Gronlund, E. (1993). How to make achievement tests and assessments. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Harcourt Educational (2002). Stanford Achievement Test (10th ed.). San Antonio, TX: Author.

- Hoover, H. D., Dunbar, S. B., & Frisbie, D. A. (2001). Iowa Tests of Basic Skills. Itasca, IL: Riverside.

- Mardell-Czudnowski, , & Goldenberg, D. S. (1998). Developmental indicators for the assessment of learning (3rd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services.

- Rudner, (1994, April). Questions to ask when evaluating tests (ERIC/AE Digest, EDO-TM-94-06). Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation.

- Whiston, C. (2000). Principles and applications of assessment in counseling. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Woodcock, W., McGrew, K. S., & Mather, N. (2001). Woodcock–Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.