This sample Advertising Psychology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Principles of psychological science have been applied to advertising practice since both fields were relatively young. The study of information processing, attitudes, and persuasion creates a foundation for advertising psychology because each is an important determinant of achieving advertising’s main functions: to inform, persuade, and influence.

- Introduction

- The Psychological Study of Advertising

- Perception

- Memory and Learning

- Attitudes

- Persuasion

1. Introduction

The Advertisers Handbook, published in 1910 by the International Textbook Company, offered a wide range of advice to advertising professionals. According to the handbook, an advertisement should not be too general, a headline should not be silly or deceptive, and an ad should be arranged logically, be concise, contain a proper amount of matter for the commodity being sold, and so forth. A few pages of the handbook were even devoted to the use of psychology in advertising: ‘‘Study of the goods or service to be sold is highly important, but no more important than the study of that wonderful subject, the human mind. The advertiser will do well, in all his work, to give special attention to psychological principles.’’

The handbook’s advice has been heeded. Advertisers have used both psychological theory and method to gain a better understanding of consumers. The study of information processing has been particularly influential as advertisers have sought to gain consumers’ attention and ensure that consumers interpret and understand their messages and (hopefully) retain some of the information. The attitude construct has been particularly important in advertising psychology because advertisements are generally intended to create positive attitudes toward some objects and because attitudes are an important determinant of behavior. Thus, an understanding of attitudes is doubly important for advertisers given that attitudes are both desired outcomes and causes of desired behavior. Therefore, the psychological study of attitude change, or persuasion, is another crucial part of advertising psychology. This research paper reviews important aspects of psychology that also play an important role in advertising.

2. The Psychological Study Of Advertising

2.1. Historical Perspectives

The scientific study of psychology is roughly 125 years old, with the first laboratory of psychology being founded in 1879 by Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig, Germany. Modern advertising is only slightly older than scientific psychology, having appeared in the earliest newspapers circa 1850, reaching a circulation of approximately 1 million readers. The two fields came together in the earliest application of psychological principles to advertising practice in America in 1896. At the University of Minnesota, Harlow Gale conducted systematic studies of the influence of ad placement within a page on attention, the impact of necessary versus superfluous words in headlines, and how various colors used in ads might influence readers’ attention.

Gale’s research did not receive wide attention, but several years later another researcher, Walter Dill Scott, wrote a series of research papers on psychological aspects of advertising. Scott’s research on advertising psychology tended to focus on the concept of suggestion. He believed that advertising was primarily a persuasive tool, rather than an informational device, and that advertising had its effect on consumers in a nearly hypnotic manner. People were thought to be highly susceptible to suggestion, under a wide variety of conditions, so long as the suggestion was the only thought available to them. According to Scott, advertising was most effective when it presented consumers with a specific direct command. ‘‘Think Different,’’ a suggestion used by Apple Computer, is a good example of a direct command, but it would not necessarily be an effective advertisement because it does not tell consumers how to think differently. A more effective advertisement might be ‘‘Use Apple Computers.’’

2.2. Contemporary Perspectives

It is interesting to note that the concept of suggestion went out of style for some time among scientific psychologists. It is somewhat unflattering to think of people as automatons who unthinkingly follow whatever instruction is given to them; however, contemporary scientific psychologists have once again embraced the notion that a fair proportion of human behavior is due to influences of which people are entirely unaware. One intriguing line of contemporary research has shown that simply asking people whether they intend to purchase a new car sometime during the next year dramatically increases the chances that they actually do purchase a new car during that year—even if they respond ‘‘no’’ to the initial inquiry. Remarkable as these ideas are, advertising has relied on a number of basic, tried-and-true psychological principles that are covered in the remainder of this research paper.

One very general model of advertising effects, the AIDA (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action) model, has roots in Scott’s writings. In 1913, Scott proposed a model of advertising effects that had three stages: attention, comprehension, and understanding. Over the course of several decades, Scott’s model evolved into the AIDA model, which is still in use. According to this model, advertising, or promotions more generally, must first garner the attention of consumers and help them to develop beliefs about the product or service. Second, advertising should create interest or positive feelings about the product /service. Third, advertising or promotions should instill in consumers a desire for the product /service, thereby helping them to form purchase intentions. Finally, consumers must be convinced to take action, that is, to purchase the product /service. This research paper covers all of these aspects of advertising psychology and more. It is important to note, however, that the AIDA model represents a strong version of advertising effects.

2.3. Strong and Weak Models of Advertising Effects

Advertising can strongly persuade consumers into immediate buying, or it can have a more subtle effect by reinforcing people’s existing propensities to buy certain brands. The psychological processes underlying these two mechanisms also differ. The strong model focuses on consumers’ immediate psychological or behavioral reactions where explicit advocacy and rationales of advertising messages are vital. The weak model emphasizes brand awareness where advertising is viewed as a reminder of a brand or source of information. For example, according to the strong model, Mark may decide to go to the shopping mall immediately after viewing a television commercial that says, ‘‘40% off any purchase at Macy’s.’’ On the other hand, David may buy Coke instead of Pepsi because he has greater familiarity with the Coke brand name, although both brands were initially in his consideration set.

Whether the strong or weak theory provides a better explanation for advertising effects hinges on numerous factors. For example, strong effects are more likely to occur in ‘‘high-involvement’’ situations where advertising directly aims at changing individuals’ attitudes. However, when consumers have a predetermined set of alternative brands or are in a ‘‘repeat buying’’ situation where purchase decisions tend to be habitual, weak reinforcement enhances long-term brand awareness, familiarity, salience, and brand associations. In any event, for advertising to have either strong or weak effects, it must first be perceived by prospective consumers.

3. Perception

The first issue is the process of getting the advertising ‘‘into’’ consumers. The sheer amount of stimuli around people is quite overwhelming. Consider all of the following stimuli to which people are constantly being exposed but are unconsciously ‘‘filtering out’’: the air rushing into their mouths or nostrils as they breathe, the sensation of tightness where their shoes are touching their feet, the color of the walls nearest them, and so forth. When one considers all of these things, it is remarkable that any advertising makes it into people’s consciousness at all. Nevertheless, if advertising is to reach consumers, they must first and foremost be exposed to it.

3.1. Exposure

Exposure is the first stage in perception, and it occurs when people achieve physical proximity to some stimulus. Whenever something activates their sensory receptors, it means they have been exposed to that something. A printed advertisement must activate rods and cones in people’s eyes, and a radio advertisement must move the small bones that make up people’s inner ears.

This activation of sensory receptors may occur at different threshold levels, with the lower, terminal, and difference thresholds being important to advertisers. The lower threshold is the minimum amount of stimulus that is necessary for people to be aware of a sensation. Images presented very briefly (i.e., a few milliseconds) fall below the lower threshold and are imperceptible to people. The terminal threshold is the point at which additional increases in stimulus intensity produce no awareness of the increase. The difference threshold is the smallest noticeable change in stimulus intensity. These threshold levels have aroused interest among advertisers due to their application to subliminal advertising.

During the late 1950s, Jim Vicary claimed to be able to influence people without them even knowing that they had been exposed to influence attempts. Vicary claimed to have increased soft drink and popcorn sales by subliminally presenting messages to movie viewers. Years later, Vicary confessed to fabricating his claims, but the notion that people could be subliminally influenced took hold somewhere in the popular imagination. Sporadically throughout the next several decades, the question of whether subliminal presentation of persuasive messages could influence consumer behavior was debated. It is now known that subliminal presentation of stimuli can influence attitudes and behavior, but not quite in the way that Vicary suggested.

In 1968, Robert Zajonc discovered that positive attitudes can be induced simply by repeatedly exposing people to a subliminally presented stimulus, a finding that he termed the ‘‘mere exposure’’ effect. Participants in these studies were repeatedly exposed to a set of unfamiliar stimuli (e.g., Chinese ideographs), although the exposures were so fast that participants were unaware of even having seen the stimuli. Yet, when asked to evaluate a variety of similar stimuli, some of which they had been exposed to and others of which had not been presented to them, they evaluated the stimuli to which they had been previously exposed more positively than they evaluated similar stimuli that had not been presented to them subliminally. Of course, developing favorable attitudes toward something is a long way from actually getting people to buy something; however, it is now known that subliminal presentation of stimuli can also influence behavior.

Individuals can be ‘‘primed’’ by the subliminal (or even supraliminal under certain conditions) presentation of stimuli in essentially the same way that they prime a pump (i.e., by filling it with fluid so that it is ready for immediate use). Following the presentation of a primed concept, individuals are more likely to use that concept given an appropriate opportunity. For example, individuals primed with the concept of elderly were observed to walk slower than individuals primed with neutral concepts. However, priming is a relatively weak influence on behavior and simply could not make people get up in the middle of a movie to go fetch soft drinks and popcorn. There are far more effective ways in which to influence consumer behavior.

3.2. Attention

One of the enduring problems facing advertisers is attracting consumers’ attention. ‘‘Zipping and zapping’’ behavior is extremely common; television viewers record programs and zip (fast-forward) through the commercials or zap (eliminate commercials during recording or change the channel when they appear) them altogether. Drivers change the radio station when advertisements come on, they look away when billboards annoy them, and so forth. Attention is simply the conscious allocation of cognitive resources to some stimulus, but it is hard to grab.

A number of strategies have been used by advertisers to attract consumers’ attention. Theories of human motivation have been popular guidelines for advertisers. For example, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs posits five levels of motives that are common to all people: physiological (e.g., food, sex), safety (e.g., protection from the elements), belongingness (e.g., acceptance by others), esteem (e.g., admiration of others), and self-actualization (e.g., fulfillment of potential). Advertisers have tried to attract attention by positioning their products to fulfill one or more of these needs. Exercise equipment and healthy food appeal to physiological needs, bicycle helmets and smoke alarms appeal to safety needs, mouthwash and acne creams appeal to belongingness needs, designer clothing and luxury automobiles appeal to esteem needs, and computer software and military service have even been made to appeal to self-actualization needs. One might imagine that nearly any product can be positioned to appeal to nearly any need—all in the name of attracting attention.

Properties of the stimulus can also be manipulated to attract attention. Size, color, intensity, contrast, position, movement, novelty, and so forth all can be used to attract attention.

3.3. Interpretation

Interpretation is the way in which meaning is assigned to stimuli. People exposed to exactly the same stimulus may interpret it very differently. For example, they may perceive a fuzzy kitten as an adorable target for cuddling or as a loathsome beast that causes sneezing and hives. Individual, situational, and stimulus characteristics all can influence the interpretation of stimuli.

At the individual level, consumers’ expectations, motives, and attitudes all can have a profound influence on they way in which they interpret advertisements. When clear cola was introduced, consumers expected it to taste different from the traditional caramel-colored colas; however, clear cola did not taste much different from brown colas, and many consumers were turned off by this. The violation of their expectations may have, at least in part, caused them to ultimately reject the clear cola. Motives and attitudes are particularly likely to have an influence on the interpretation of ambiguous stimuli. Advertisers who do not send clear messages may be opening themselves up to very different, and possibly unflattering, interpretations that reflect consumers’ own motives and attitudes.

At a situational level, the context in which an advertisement appears can have an influence on how it is interpreted. Several years ago, a prominent newspaper put out a Sunday supplement that featured a lengthy research paper on starvation and drought in Africa, followed immediately by a lengthy pictorial on the coming season’s high-fashion formal wear. The following week, there was a section in the same supplement that was devoted to outraged letters from readers and a formal apology by the newspaper. Rarely are pictorials on fashion the target of so much outrage, but the context made a huge difference.

At a stimulus level, interpretations vary a great deal as well. As noted previously, stimulus ambiguity opens doors for motives and attitudes to have their influence on interpretations. Other stimuli can have vastly different interpretations due to cultural differences.

Different colors and numbers have different culturally laden meanings in different countries. There used to be a brand of cold medicine called ‘‘666.’’ This brand likely did not fare well among conservative Christian consumers; but it might be prized in cultures where the number six has a positive meaning.

4. Memory And Learning

Memory is complex; we can remember toys that we wanted as children, yet we sometimes cannot remember what we did the weekend before last. The simple change of a single word (e.g., how fast was the car going when it ‘‘bumped’’ [or ‘‘smashed’’] into the pedestrian?) can substantially alter our memories. Yet it has been estimated that over the course of a lifetime, the average human stores approximately 500 times the amount of information that is in a full set of encyclopedias. Given these seemingly strange contradictions regarding memory, what hope can advertisers have of getting their products, brands, and ideas into consumers’ memories?

4.1. Encoding, Storage, and Retrieval

Memory involves three main processes: encoding (the process by which information is put into memory), storage (the process by which information is maintained in memory), and retrieval (the process by which information is recovered from memory).

Encoding may be visual, acoustic, or semantic. Visual encoding and acoustic encoding are self-explanatory; they are named for the sensory modality through which they operate. Semantic encoding refers to the general meaning of an event. For example, one might encode a television advertisement in terms of the visuals presented, the sounds that accompany it, or the general idea that there is a sale at the market.

Storage may be short term or long term. Short-term memory, or working memory, is of quite limited capacity and is used to hold information in consciousness for immediate use. Long-term memory is quite vast and can retain information for extremely long periods of time (e.g., some childhood memories last until death).

Retrieval also comes in different forms. Explicit memory is tapped by intentional recall or recognition of items or events. Implicit memory is the unintentional recollection and/or influence of prior experience on a current task. On implicit memory tests, respondents are unaware that memory is being accessed. Implicit memory is assessed in a variety of ways such as word fragment completion (words seen previously are more likely to be completed than are words not seen previously) and time savings for tasks that have been done before. Advertisers may be particularly interested in explicit memory because the ability to intentionally recall information serves as a good measure of advertising effectiveness.

4.2. Short and Long-Term Memory

Short-term memory is of relatively little consequence to advertisers because it does not, by definition, have any ‘‘staying power.’’ Short-term memory may be important for direct response advertising, where consumers are asked to call a phone number to order or request additional information. But there is little that an advertiser can do with short-term memory. The primary function of short-term memory is to allow people to perform mental work such as calculating a sums or remembering a telephone number until they can either dial it or write it down. The fairly recent trend of placing advertisements on shopping carts in supermarkets might be a good way for advertisers to keep their products in short-term memory while people are doing their grocery shopping. In general, however, for an advertisement to be effective, it must work its way into long-term memory.

One bright spot for advertisers hoping to etch their work in consumers’ long-term memory is the fact that most theorists believe that long-term memory has nearly unlimited capacity. So, there is always room for more information. But what is the best way in which to achieve storage in long-term memory?

Some information is stored in long-term memory accidentally (i.e., unintentionally), but most information that makes it to long-term memory is encoded semantically. According to one model of memory, information is better remembered when it is thoroughly processed. To the extent that people elaborate on, and think deeply about, a particular piece of information, they are more likely to be able to recall it later. This notion of cognitive elaboration is important in the understanding of persuasion as well. Clearly, advertisers would do well to generate ads that cause people to think deeply or discuss extensively. According to another model of memory, retrieval is enhanced to the extent that learning and retrieval occur under similar conditions. This bodes poorly for advertisers given that the encoding and storage of advertising rarely occur under the same conditions as the actual buying behavior. Advertisements tend to be absorbed most everywhere except the marketplace.

4.3. Processing Pictures Versus Text

Pictures enhance advertising effectiveness in several ways: They help to get the audience’s attention, they provide information about the brand and product use, and they help to create a unique brand image. Because people examine the visual elements before the verbal elements, pictures in advertising are a useful tool as attention grabbers. For example, extensive use of sex appeal and celebrity endorsement in advertising can be understood in this context.

Images and text are processed differently. Pictorial information seems to be processed more holistically, whereas verbal information is processed more sequentially. Information conveyed by pictures is recalled and recognized more easily than is textual information. Therefore, the fact that more than two-thirds of print advertisements today have pictures covering more than half of the available space is not surprising. So, why are pictures more memorable than words?

According to Paivio’s dual-coding model, different codes exist in memory for verbal material and pictorial material. Pictures tend to be remembered over verbal information because they activate both verbal codes and pictorial codes spontaneously. This ease of cognitive access leads to the facilitation of memory. In addition, ads with concrete, easily identifiable pictures (e.g., celebrities) or realistic pictures are more memorable than ads with abstract or unidentifiable pictures. Furthermore, consumers exhibit more favorable attitudes when they see identifiable objects (e.g., an Adidas logo, a picture of Michael Jordan) than when they simply view text (e.g., the combination of alphabetical letters P-U-M-A).

Memory effects of text vary depending on how difficult it is for perceivers to comprehend the text. When the text is complex, people engage in more elaborative processing, resulting in a greater number of associations in memory as well as improved memory. Finally, pictures and text interact. Congruency between pictures and ad copy enhances consumers’ recall.

4.4. Repetition and Learning

Advertising repetition is generally known to enhance memory by strengthening memory traces because it increases redundancy and provides more encoding opportunities to process the message, leading to higher levels of brand name recall. Nevertheless, advertising repetition rarely works in such simple ways. For example, varying the interval between message repetitions affects memory of an advertising message. Although not without exceptions, memory for repeated material generally improves as the time between presentations of advertising material increases, particularly when there is a delay between the subsequent presentation of the stimulus and the memory test.

Another explanation of learning through repetition is derived from encoding variability theory, which predicts that presenting a series of ads containing slight variations of a theme enhances memory for the ad material. For example, according to this view, repeated presentation of a bottle of Absolut Vodka in different contexts helps consumers to retain its brand name in their memory.

Attention, recall, and brand awareness initially increase, then level off, and ultimately decline as the number of exposures increases. At least two explanations are available for this ‘‘wear-out’’ effect: inattention and active information processing. With increasing repetition, viewers no longer attend to the message, and this inattention causes forgetting. According to the active information processing perspective, an audience rehearses two kinds of thoughts: thoughts stimulated by the message reflecting message content (i.e., message-related thoughts) and other thoughts based on associations reflecting previous experiences (i.e., people’s own thoughts). With the initial exposure to a message, people’s thoughts tend to be message related, but at some level of repetition, people’s thoughts stem mainly from associations that are only indirectly linked to the message. These thoughts are less positive toward the product than are message-related thoughts, primarily because the latter were selected to be highly positive.

4.5. Low and High-Involvement Learning

Learning may occur either in a situation where consumers are highly motivated to process the advertising material or in a situation where consumers have little motivation to learn the material. For example, a woman reading an automobile magazine in a dentist’s office is less involved than another woman reading the same magazine prior to purchasing a new car. Personal, product, and situational factors jointly affect the level of involvement. A different level of involvement is likely to follow, for example, depending on whether the individual perceives the advertised product as enhancing self-image (i.e., personal factor) or entailing risk (i.e., product factor). And this whole perception of the product will again be influenced by whether the consumer views the product for personal use or views it as a gift (i.e., situational factor).

High involvement stimulates semantic processing, whereas low involvement is linked to sensory processing. Text-based information is better remembered when viewers are highly involved, whereas graphic oriented information exerts a greater impact on viewers’ memory when they have low involvement. The study of learning and memory is important for understanding how consumers obtain information about a product or service. Another primary goal of advertising is to persuade, so the next section considers the psychological study of attitudes and persuasion.

5. Attitudes

The attitude construct has been recognized as one of the most indispensable concepts in psychology. It is similarly crucial in the study of advertising. But what exactly is an attitude? For a psychologist or an advertiser, an attitude refers to an evaluation along a positive–negative continuum. For purposes of this research paper, an attitude is defined as a psychological tendency to evaluate an object with some degree of favor or disfavor. The target of an attitude is called the attitude object. When an individual says, ‘‘This pie is lovely’’ or ‘‘That car is no good at all,’’ that person is expressing his or her attitudes. When the individual says, ‘‘This pie is fattening’’ or ‘‘That car has poor acceleration,’’ the person is expressing his or her beliefs. Attitudes are different from beliefs, although the latter help to make up the former. Beliefs are units of information that an individual has. Beliefs may be facts or opinion, and they may be positive, negative, or neutral with regard to the target.

5.1. The Structure of Attitudes

Attitudes are generally not thought of as monolithic constructs; they are made up of conceptually and empirically distinct components. At a very basic level of analysis, attitudes have three important components: affective, behavioral, and cognitive. Affect refers to feelings and emotional components of attitudes. Behavior, of course, refers to behavior that an individual takes with regard to a target. Cognition refers to the beliefs or thoughts that an individual has about a target.

Affective, behavioral, and cognitive processes help to form attitudes. The mere exposure effect suggests one way in which positive affect may arise. Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are two additional ways in which affective processes influence people’s attitudes. The continuous pairing of some stimulus and a reward (or punishment) creates positive (or negative) affect. In advertising, brands of clothing are nearly always paired with attractive models. The models are intended to create affectively positive feelings, and advertisers hope that people will be conditioned to like their brands of clothing.

Behavior also contributes to the formation of attitudes in that sometimes people infer their attitudes on the basis of their previous behavior. Self-perception theory posits that people infer their attitudes on the basis of their past behavior, particularly when they believe that their behavior has been freely chosen. For example, if someone points out that Jane always wears green, she may infer that she has some affinity for green. But if Jane always wears green because her school has a strict dress code requiring her to wear green, she is unlikely to infer that she has a favorable attitude toward green.

Cognition is another important antecedent of people’s attitudes. A cognitively based learning process occurs when people acquire information about attitude objects. People may gain information through direct experience such as when a free trial product is sent in the mail or when a free sample is offered in a store. Or, people may gain information indirectly, for example, when a television commercial shows them the benefits of owning a particular make and model of automobile. People’s beliefs about attitude objects have been proposed as a central determinant of attitudes. Indirect learning, or observational learning, is an important tool for advertisers. Consider any advertisement that shows a model using a product to benefit in some way. It is hoped that viewers will develop favorable attitudes toward the product by learning how others have benefited from the product.

So, attitudes generally have affective, behavioral, and cognitive components. However, it is not necessary for all attitudes to have all three components. Some attitudes may be based primarily on affective factors (e.g., attitudes toward tequila), and others may be based primarily on cognitive factors (e.g., most people probably feel mildly positive about photosynthesis due to the important functions performed by the process, but they probably do not have strong emotions about it).

One very influential model of the structure of attitudes is Martin Fishbein’s expectancy-value model.

Fishbein proposed that attitudes are a multiplicative function of two things: (a) the beliefs that an individual holds about a particular attitude object and (b) the evaluation of each belief. According to the expectancy value model, beliefs are represented as the subjective probability that the object has a particular attribute. The model can be expressed as a mathematical function:

where Ao is the attitude toward the object, bi is a belief about the object, and ei is the evaluation of that belief. According to Fishbein, people’s attitudes are typically based on five to nine salient beliefs. So, if a researcher wanted to know someone’s attitude toward a particular brand of clothing, the researcher might ask that person to estimate the likelihood that a particular brand has a variety of attributes (e.g., fashionable, durable, well priced) and how positive or negative each of those attributes is. The researcher could then compute an estimate of the person’s attitude by multiplying the pairs of scores and then summing the products.

The expectancy-value model also implies that persuasion is largely a function of message content. That is, favorable attitudes can be produced by making people believe that an object is very likely to have some desirable trait, by making people believe that some trait is very favorable, or by both. For example, an advertiser might endeavor to make people believe that its automobile is very reliable (i.e., influence the subjective probability of beliefs) or to make people believe that its automobile’s ability to take turns at very high speeds is highly desirable (i.e., influence the evaluation of a particular attribute).

Although the expectancy-value model seems to be perfectly logical, it may seem surprising to suggest that all attitudes are based on a series of beliefs. Consider, for example, the mere exposure research discussed earlier. According to Zajonc, preferences need no inferences (i.e., people may like something without having any beliefs about it). Under some conditions, attitudes may be formed outside of people’s conscious awareness, or attitudes may be directly retrieved from memory rather than ‘‘computed’’ based on a mental review of salient beliefs. However, it is generally accepted that highly elaborated attitudes are more influential than poorly elaborated attitudes. So far, the discussion of attitude structure has considered how different aspects of a single attitude relate to one another. Next, the discussion considers how different attitudes relate to one another.

One of the most enduring psychological principles developed during the 20th century is the simple notion that people have a desire for cognitive consistency. Cognitive consistency is the simple notion that beliefs and actions should be logically harmonious. If an individual believes that cats make good pets but hates her pet cat, she has beliefs that are inconsistent; if an individual believes that cats make good pets and she loves her cat, she has beliefs that are consistent. For most people, cognitive inconsistency is unpleasant, so they take steps to achieve consistency.

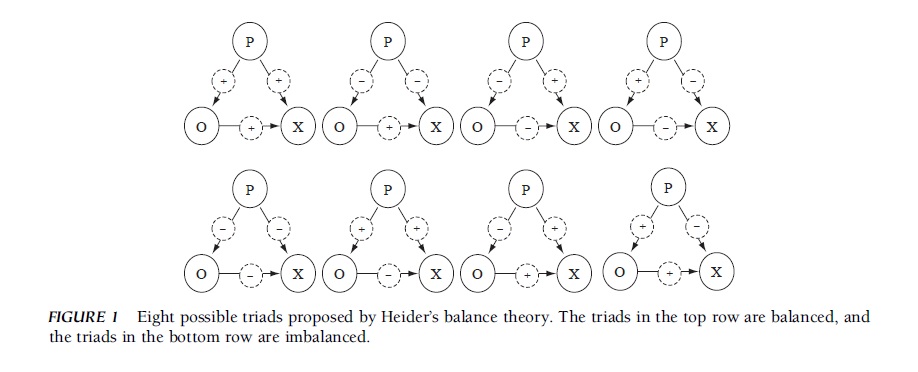

One consistency theory with many advertising-related applications is Heider’s balance theory. Balance theory was initially applied to cognitive consistency between dyads (two units) and among triads (three units), but because most research has examined triads, this research paper focuses on this arrangement. The triad arrangement pertains to the attitudinal relationships among a perceiver (p), an other (o), and an attitude object (x). Consider the example where Cody has recently met an individual named Sam, and Cody likes Sam quite a bit. One afternoon, Cody learns that Sam loves to listen to country music. However, Cody cannot stand country music. How does the fact that Sam loves country music make Cody feel? Probably not very good; the triad of Cody, Sam, and country music is not balanced. However, if Cody loved country music, Cody liked Sam, and Sam loved country music, all would be simpatico. These ideas illustrate the basic tenets of Heider’s balance theory. As can be seen in Fig. 1, there are eight possible sets of relationships among the triads: four balanced and four imbalanced. One simple way in which to identify whether a triad is balanced or not is to calculate the product of the three relationships. If the product is positive, the triad is balanced; if the product is negative, the triad is imbalanced.

The efficacy of well-liked, or celebrity, endorsers may be explained at least in part by evoking balance theory. The viewers of the advertisement are expected to have a favorable attitude toward the endorser (e.g., Britney Spears), and the endorser is clearly portrayed as having a positive attitude toward the advertised product (e.g., cola). To maintain balance, viewers also should adopt a positive attitude toward the cola. Alternatively, viewers could decide to dislike the cola and change their attitude toward Spears so as to maintain a balanced triad. Balance theory also helps to explain one way in which consumer trends migrate. People who become friends with one another often adopt attitudes similar to their friends’ attitudes. A classic study by Theodore Newcomb illustrated this point with women who lived together at college; over time, the women’s political attitudes became more and more similar.

FIGURE 1 Eight possible triads proposed by Heider’s balance theory. The triads in the top row are balanced, and the triads in the bottom row are imbalanced.

FIGURE 1 Eight possible triads proposed by Heider’s balance theory. The triads in the top row are balanced, and the triads in the bottom row are imbalanced.

Another theory that has roots in cognitive consistency, and has been very influential in advertising and consumer behavior, is cognitive dissonance theory. Leon Festinger proposed cognitive dissonance theory in 1957, and it spurred more research than perhaps any other social psychological theory. Cognitive dissonance has been defined as a feeling of discomfort that arises as a result of one’s awareness of holding two or more inconsistent cognitions. Often, dissonance is aroused when one behaves in a manner that is inconsistent with his or her beliefs. For example, Greg may believe that Japanese cars are superior to cars made in America, but if he buys an American car, he will likely experience cognitive dissonance. Because cognitive dissonance is uncomfortable, people are motivated to reduce the feeling of dissonance by changing their behavior, trying to justify their behavior by changing their beliefs, or trying to justify their behavior by adding new beliefs. Having purchased an American car, Greg might try to reduce cognitive dissonance by investing in Japanese auto manufacturers, by changing his belief in the superiority of Japanese cars, or by adding a new belief to help regain consistency, for example, ‘‘My car may be American, but many of the engine parts are from Japan.’’

When people make large-scale purchases, they often experience what is known as post decisional dissonance. Large expenditures may arouse dissonance because they are inconsistent with the need to save money or make other purchases. Furthermore, making a purchase decision necessarily means giving up some attractive features on the unchosen alternatives (e.g., buying a Sony means not buying a Samsung). In a decision-making context, dissonance may be reduced by revoking the decision, by bolstering the attractiveness of the chosen alternative or undermining the attractiveness of the unchosen alternative, or by minimizing the differences between or among the alternatives. Another important role that advertising can play is in helping to reduce post decisional dissonance. Advertising can help to reduce the feeling of discomfort that follows a major purchase by changing beliefs (e.g., ‘‘The new MP3 player has state-of-the-art technology’’) or by adding new beliefs (e.g., ‘‘The new MP3 player will make you the envy of your friends’’) that enable buyers to feel good about their recent major purchases.

5.2. Functions of Attitudes

Why do people have attitudes? Consider, for a moment, what life would be like without attitudes. For example, Tracy might sit down to dinner one day to find a plate of lima beans. She might eat the beans and discover that they taste horrible. The following week, Tracy is once again served lima beans and remembers them from the last time, but she has no attitude toward them. She eats them again and finds out, once again, that they taste quite horrible. For someone without attitudes, the discovery that lima beans are horrible could occur hundreds of separate times over a lifetime. At a most basic level, attitudes help people to navigate their world; they help them to know how to respond to things. Attitudes allow people to approach rewards and avoid punishments. Beyond this basic ‘‘object appraisal’’ function, attitudes have long been thought to serve a number of important functions. More than 40 years ago, Daniel Katz described four functions of attitudes: ego-defensive, value-expressive, knowledge, and utilitarian. Some attitudes have an ego defensive function in that they help protect people from unflattering truths about themselves. People may bolster their own egos by holding negative attitudes about other groups (e.g., Hispanics, homosexuals). The value-expressive function occurs when attitudes allow people to express important values about themselves. For example, people may express a positive attitude toward recycling, suggesting that environmentalism is an important value. The knowledge function of attitudes allows people to better understand the world around them. For example, if a person dislikes politicians, it is easy to understand why politicians always seem to be giving themselves pay raises when the economy is particularly weak. Finally, attitudes may have a utilitarian function. Tracy’s attitude toward lima beans helps her to know whether to approach them (because they are delicious) or avoid them (because they taste horrible). As suggested by all of these functions, attitudes also help to guide people’s behavior.

5.3. Attitude–Behavior Relations

Indeed, the study of attitudes was at least partly initiated because attitudes seemed to be a logical predictor of behavior. As noted earlier in the research paper, behavior is an important form of attitudinal expression. For example, if Tara has a positive attitude toward a brand of pants, it follows that she will buy the pants; she will behave in a way that is consistent with her attitudes. Advertisers aim to create positive attitudes toward objects in the hope that consumers will purchase those objects. Unfortunately, the study of attitude–behavior relations has not been quite so simple. The following is only a very brief review of attitude–behavior relations.

A 1969 review of the literature on attitude–behavior relations found that attitudes and behaviors were modestly correlated with one another at best. This lack of attitude–behavior correspondence caused some researchers to suggest abandoning the attitude concept altogether. Fortunately, others rejected this suggestion and worked to better understand attitude–behavior relations. It is now known that attitudes reliably predict behavior under certain conditions. Attitudes and behaviors correlate when the attitude measures and behaviors correspond with regard to their level of specificity. If one wants to reliably predict a specific action, one should assess attitudes toward performing that action, with regard to a particular target, in a given context, and at a specific time. Or, one could enhance attitude– behavior correspondence by broadening the scope of the behaviors. Knowing someone’s attitude toward a particular attitude object (e.g., religion) is not necessarily going to predict whether that person attends church on a given Sunday, but it should reliably predict a variety of religious behaviors over the course of time (e.g., attending religious services over a period of weeks, having a religious text at home, wearing a symbol of religious faith).

Another way in which to enhance the attitude–behavior relationship is to provide people with direct experience with attitude objects. Indirect learning is not as powerful as direct learning, so an advertisement showing people enjoying a frosty beverage is not as persuasive as having people enjoy the frosty beverage in person. Behavioral prediction is enhanced when one also considers the influences of social norms and perceived control on behavior. Finally, attitudes are more predictive of behavior when attitudes are strong or readily accessible.

Attitude strength has been defined and measured in a variety of ways, but it is generally accepted that strong attitudes are resistant to change, persistent over time, and predictive of behavior. Clearly, these are the types of attitudes that advertisers want to inculcate. But given that there are multiple definitions of attitude strength, what is the best way in which to identify and produce strong attitudes? In considering various measures of attitude strength, it may be helpful to think in terms of whether the measures are operative or meta-attitudinal. An operative measure of attitude strength is one that reflects the operation of the attitude (e.g., the accessibility of the attitude can be measured by the speed with which people can provide evaluations of objects), whereas a meta-attitudinal measure of attitude strength is one that requires people to provide a subjective self report of their own attitudes (e.g., the confidence with which an attitude is held cannot be directly measured but rather must be reported by an individual). One way in which attitudes can be strengthened is through cognitive elaboration. To the extent that people intentionally and carefully think about, and elaborate on, their attitudes, they are engaged in cognitive elaboration.

6. Persuasion

The study of attitude change has existed since Aristotle’s time. However, empirical research on persuasion and attitude change is a much more recent phenomenon. It was not until the mid-20th century that the study of attitude change developed into a thoroughly systematic process.

6.1. Message Learning Approach

Carl Hovland and colleagues, working at Yale University during the 1950s, sought to study persuasion by considering the question, ‘‘Who says what to whom with what effect?’’ That is, they were interested in studying the effects of different variables in the persuasion process.

‘‘Who’’ refers to the source of the persuasive communication, ‘‘what’’ refers to the message that is presented, and ‘‘to whom’’ refers to characteristics of the message recipient. This approach to the study of persuasion was an information-processing, or message-learning, paradigm. According to the message-learning paradigm, persuasive communications could have an effect only to the extent that they commanded attention and were comprehensible. Furthermore, message recipients had to yield to the persuasive communications and retain the information presented in the persuasive communications. If these conditions were met, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors were liable to change. The following considers some of the critical variables studied by the Yale group.

Holding message, recipient, and channel characteristics constant, how do different characteristics of the source influence persuasion? Hovland and colleagues found that communicator credibility had an effect on persuasion, such that credible sources were more persuasive than noncredible sources. But what exactly is a credible source? Hovland and colleagues examined three characteristics of credible sources: expertise, trustworthiness, and the source’s intent to persuade. An expert source (e.g., a Nobel prize-winning scientist) is more persuasive than a nonexpert source (e.g., the director of a local YMCA). A trustworthy source (e.g., a news anchor) is more persuasive than a nontrustworthy source (e.g., a member of the Liars Club). A source that is known to have a persuasive intent (e.g., an advertisement) is often less persuasive than one delivering the same message but with no persuasive intent (e.g., a friend). Forewarning people of a communicator’s persuasive intent seems to instigate mental counter arguing in the audience. It is also known that physically attractive sources are generally more persuasive than unattractive ones and that similar communicators are usually more persuasive than dissimilar ones. Finally, powerful communicators (i.e., communicators who can administer punishments or rewards to the message recipients) tend to be more persuasive than powerless communicators.

Holding source, recipient, and channel characteristics constant, how do different characteristics of the message influence persuasion? The comprehensibility of a message is (obviously) an important determinant of persuasion; if people cannot understand the message, it is unlikely that they will be persuaded by it. The number of arguments in a persuasive communication also matters; more arguments are generally better than fewer arguments. Of course, there is a limit to the number of arguments one can present before message recipients become annoyed and lose interest. Presenting a few strong convincing arguments is better than presenting dozens of weak specious arguments. Messages that arouse fear (e.g., ‘‘If you do not brush your teeth, you will end up ugly, toothless, and diseased’’) can also be persuasive if certain conditions are met. An effective fear appeal must (a) convince the recipients that dire consequences are possible, (b) convince the recipients that the dire consequences will occur if instructions are not followed, and (c) provide strong assurance that the recommended course of action will prevent the dire consequences. One and two-sided messages are differentially persuasive for different audiences; two-sided messages are generally more effective among knowledgeable audiences, whereas one-sided messages are more effective among less knowledgeable audiences. Two-sided messages can be more effective in general so long as the opposing arguments are effectively countered in the message.

Recipient characteristics also influence the efficacy of persuasive communications. An audience that is highly motivated and able to process information is more apt to be persuaded (provided that strong, rather than weak, arguments are presented) than is an audience that is distracted or apathetic. People who are of lower intelligence are generally easier to persuade than are people of high intelligence, people with moderate levels of self-esteem are generally easier to persuade than are people with either low or high self-esteem, and younger people are more susceptible to persuasive communications than are older people. Some personality traits also have important implications for persuasion. Self-monitoring is a characteristic that varies in the population. High self-monitors are particularly sensitive to situational cues and adjust their behavior accordingly, whereas low self-monitors are guided more by internal cues and tend to behave similarly across various situations. High self-monitors tend to be susceptible to persuasive communications that have image-based appeals, whereas low self-monitors tend to be more susceptible to value or quality-based appeals.

6.2. Dual-Process Theories

The message-learning approach to persuasion obtained a great deal of information about the influence of different variables on persuasion. However, there were also a lot of apparently contradictory findings. One study might report that attractive sources had a large impact on persuasion, whereas another study would report no impact at all. During the late 1970s, a pair of integrative frameworks for understanding persuasion emerged. The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and the Heuristic– Systematic Model (HSM) are both dual-process models of persuasion, emphasizing that different variables can have different effects on persuasion. These models are fairly similar to one another and can be used to explain similar findings and make similar predictions, but the language used in describing the two models is different. The focus here is on the ELM because it has spurred the most research in advertising and marketing.

The ELM is based on the proposition that there is a continuum of elaboration likelihood. At one end of the continuum, the amount of cognitive effort that is used to scrutinize persuasive communications is negligible; information processing at this end of the continuum is minimal. This is known as the peripheral route to persuasion. At the other end of the continuum, there is a great deal of cognitive elaboration; people are highly motivated to carefully process information pertaining to the persuasive communications. This is known as the central route to persuasion. One might say that there are two routes to persuasion: central and peripheral. Which route is taken is dependent on message recipients’ motivation and ability to process information. According to the ELM, people who are both motivated and able to process persuasive communications will take the central route, whereas people who are lacking either motivation or ability to process information will take the central route.

The central and peripheral routes are metaphors for the amount of cognitive elaboration in which people engage when they are faced with persuasive communications. Central route processing is particularly likely to occur when the persuasive communications are personally relevant to the recipient. If an individual is in the market for a new automobile, automobile advertisements would likely be personally relevant and, therefore, more highly scrutinized. If a person happens to be a home theater enthusiast, he or she would be more motivated to attend to advertisements for televisions and stereo speakers. Of course, all of the motivation in the world cannot cause greater cognitive elaboration if the message recipients do not also have the ability to process the information carefully. Distractions and other forms of cognitive business would prevent cognitive elaboration.

Persuasion through the central route occurs when the arguments presented are strong and compelling, and attitudes formed through the central route are persistent over time and resistant to change. Persuasion through the peripheral route occurs when there are compelling peripheral cues present (e.g., a long list of arguments, an attractive speaker, a credible source), and attitudes formed through the peripheral route are more temporary and subject to further change. The ELM and HSM can account for a wide variety of persuasion phenomena and have proven to be very robust and useful theories.

The psychology of advertising has come a long way. We now have a greater understanding than ever before of psychological processes crucial to advertising. From attracting attention to understanding how people are persuaded, the advancement of psychological science and that of advertising practice have much to learn from one another. This research paper has but scratched the surface of advertising psychology. New theories and applications are emerging at a rate that is unparalleled in the history of either advertising or psychology.

References:

- Eagly, H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: John Wiley.

- O’Guinn, T. C., Allen, C. T., & Semenik, R. J. (2003). Advertising and integrated brand promotion. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

- Packard, V. (1957). The hidden persuaders. New York: D. McKay. Petty, E., & Wegener, D. T. (1998). Attitude change: Multiple roles for persuasion variables. In D. T. Gilbert, S.

- Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 323–390). New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Scott, L. M., & Rajeev, B. (Eds.). (2003). Persuasive imagery: A consumer response perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35, 151–175.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.