This sample Aging and Competency Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Many people use the concept of competency in clinical settings, although there continues to be confusion about what it means, when it is relevant, and how it should be assessed. All adults are presumed to be legally competent unless otherwise determined in a court of law. An adult’s competency may be questioned when a family member or other interested party files a petition for guardianship of that individual. If incompetency is found in a court hearing, a guardian or conservator may be appointed. In most states, a guardian is responsible for decisions regarding the care of the individual’s ‘‘person’’ (e.g., day-to-day issues of care, residence, and activities), whereas a conservator is responsible for decisions regarding the care of the ‘‘estate’’ (i.e., management of assets).

Outline

- Clinical Versus Legal Competency

- Competency Versus Capacity

- Legal Frameworks for Aging and Competency

- Decision-Making Abilities in Competency

- Clinical Evaluations of Capacities

- Categories of Capacities

1. Clinical Versus Legal Competency

Although clinicians may question a patient’s competency status and may request other clinicians to evaluate the patient’s competency, a clinical finding of incompetency should not be confused with a judicial determination of incompetency. The clinical use of the term ‘‘competency’’ refers to a clinical opinion regarding the patient’s decisional capacities. Such an opinion may be used to activate a durable power of attorney or health care proxy if one exists. However, clinical statements about capacities should not be equated with court-determined findings of incompetency.

2. Competency Versus Capacity

Increasingly, the term ‘‘capacity’’ is preferred to competency. The use of capacity recognizes the possibility of individual strengths and weaknesses or functional capacities rather than the all-or-none notion of incompetency.

3. Legal Frameworks For Aging And Competency

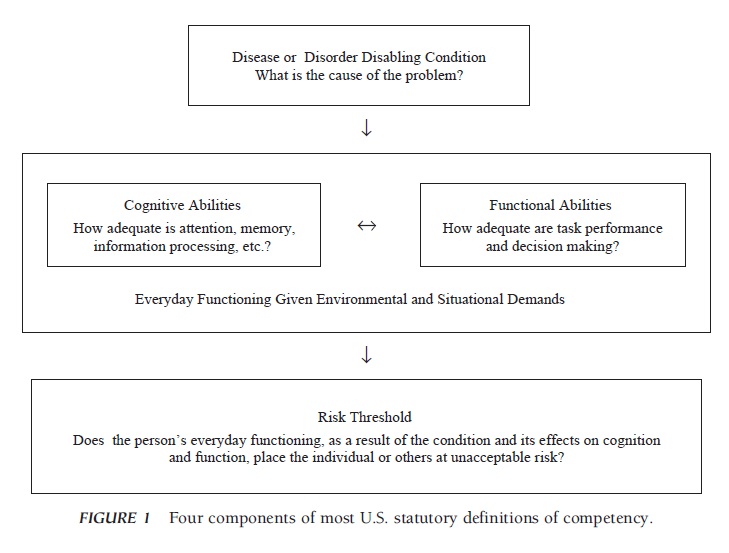

In the United States, most statutory definitions of incapacity to care for one’s person or estate include four parts, as shown in Fig. 1. This four-part definition means that a diagnosis is a necessary, but not a sufficient, component of incompetency. Rather, information must be provided as to how the disease affects attention, memory, information processing, and so forth as well as, in turn, how these symptoms affect the person’s ability to do certain things or make specific decisions. The ability level should be considered within the context of the environmental demands and resources as well as specific situational risks and benefits. For example, the threshold for the capacity to reasonably manage a small amount of day-to-day cash spending would be different from the capacity to manage a complex portfolio of investments, and the abilities needed for the capacity to consent to a relatively harmless medical intervention (e.g., a flu shot) would be much lower than those needed to consent to a more risky medical intervention (e.g., heart bypass surgery).

FIGURE 1 Four components of most U.S. statutory definitions of competency.

FIGURE 1 Four components of most U.S. statutory definitions of competency.

4. Decision-Making Abilities In Competency

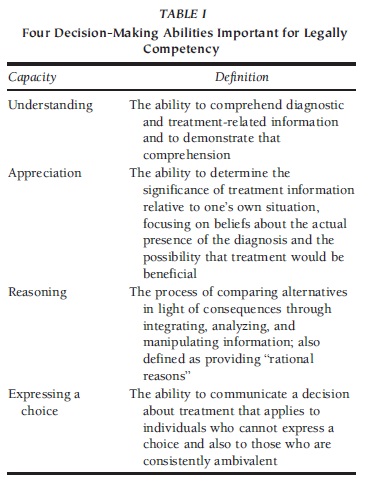

Much U.S. case law about competency to consent to treatment refers to four decision-making abilities, as shown in Table I. Case law typically refers to these abilities individually as independent legal standards. Together, they form a useful framework for evaluating decisional processes.

5. Clinical Evaluations Of Capacities

5.1. Competency and Older Adults

Although the large majority of guardianships concern elderly individuals with psychiatric or neurological diagnoses, it is clear that advancing age or physical frailty themselves are not grounds for guardianship. Competency questions are increasing for older adults due to the age-associated increase in prevalence of dementia that can affect competency during the later stages of the disease.

TABLE I Four Decision-Making Abilities Important for Legally Competency

TABLE I Four Decision-Making Abilities Important for Legally Competency

5.2. Competency Assessment

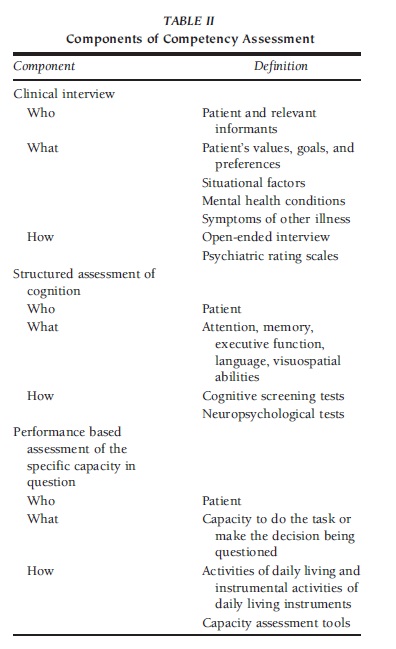

In the past, most clinical evaluations of competency relied on a physician’s interview or knowledge of the patient. However, such approaches can be unreliable. A more objective evaluation of competency, particularly important in more complicated cases, involves three parts, as shown in Table II.

5.3. Ethical Issues

5.3.1. Consequences of Guardianship

Many adults who receive guardianship experience benefit from the arrangement. In the best case, the individual receives needed care, supervision, and advocacy in accordance with his or her wishes. In the worst case, guardians may take advantage of the individual’s assets. In either case, removal of competency results in the loss of the right to make choices about residency, health care, medication, relationships, marriage, contracts, voting, driving, use of leisure time, and how one’s own money is spent. Such losses in autonomy may affect the individual’s emotional well-being. These potential rights deprivations and personal consequences of incompetency underscore the special care that should be taken in competency assessments and the extra attention that should be devoted to ethical concerns.

TABLE II Components of Competency Assessment

TABLE II Components of Competency Assessment

5.3.2. Informed Consent

An individual who is the subject of a competency evaluation needs to be informed of the nature of the evaluation and the potential consequences. Obtaining informed consent for the evaluation of competency from a person whose decision-making capacity is in question requires special care. Clinicians should fully disclose information about the evaluation and its risks and benefits in clear and direct language and then should assess the individual’s ability to understand, appreciate, and reason through the information and options.

5.3.3. Individual and Cultural Differences

Persons from different ethnic or age backgrounds may have different cultural and cohort preferences for medical care, finances, living situations, relationships, and so forth. Evaluators must be sensitive so that individual and cultural differences are not misconstrued as incompetent decisional processes. This also applies to the use of standardized tests because some do not have adequate normative data concerning cultural, cohort, and educational influences on test performance, especially in older populations. Test instruments should be given in the primary language of the person being assessed.

6. Categories Of Capacities

6.1. Financial Management

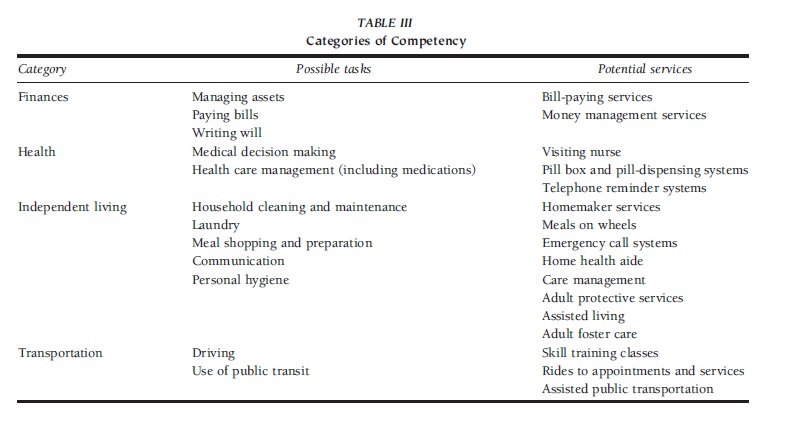

As shown in Table III, one important category of competency is the capacity to manage finances, including managing assets and how one spends money, managing debts and how one pays bills, and managing specific issues of contracts, disposition of property, and wills. Such financial capacities may involve knowledge of facts (e.g., where one’s bank account is), financial skills (e.g., counting change), and financial judgment (e.g., avoiding fraud). As indicated in the table, services can sometimes provide alternatives to guardianship.

TABLE III Categories of Competency

TABLE III Categories of Competency

6.2. Health Care

Another category of competency focuses on health care, especially the capacity to consent to treatment. Health care capacities may also cover managing day-to-day health such as nutrition, wound care, and medications.

6.3. Independent Living

A third and more broad category of competency concerns the capacity to live independently. Tasks in this category include household cleaning and maintenance, laundry, meal shopping and preparation, and communication (telephone and mail). Senior service agencies have a wealth of services to assist vulnerable adults in living independently, including homemaker services to clean, do laundry, and prepare meals; ‘‘chore’’ services to tackle larger tasks such as lawn care and snow removal; and meal delivery programs. Communication aids, including large-button telephones, assistive devices, and animals for the deaf and hard of hearing, may also promote independent living. Medical alert systems can be installed for seniors to enact in the event of a disabling emergency.

6.4. Transportation

A more narrow category of functional abilities concerns transportation and the capacity to drive a motor vehicle. This question may arise outside of other competency concerns when an adult with a disabling psychiatric or neurological condition has a series of motor vehicle accidents.

References:

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (1997). Clinical assessment for competency determination: A practice guideline for psychologists. Milwaukee, WI: National Center for Cost Containment.

- Edelstein, B. (2000). Challenges in the assessment of decision-making capacity. Journal of Aging Studies, 14, 423–437. Earnst, S., Marson, D. C., & Harrell, L. E. (2000).

- Cognitive models of physicians’ legal standard and person judgments of competency in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 48, 919–927.

- Grisso, T. (2002). Evaluating Competencies (2nd ). New York: Plenum.

- Grisso, , & Appelbaum, P. S. (1995). The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study III: Abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law and Human Behavior, 19, 149–174.

- Marson, D. C., Ingram, K. K., Cody, H. A., & Harrell, L. E. (1995). Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. Archives of Neurology, 52, 949–954.

- Marson, D. C., McInturff, B., Hawkins, L., Bartolucci, A., & Harrell, L. E. (1997). Consistency of physician judgments of capacity to consent in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 45, 453–457.

- Moye, J. (1999). Assessment of competency and decision making In P. Lichtenberg (Ed.), Handbook of geriatric assessment (pp. 488–528). New York: John Wiley.

- Moye, J., & Karel, M. J. (1999). Evaluating decisional capacities in older adults: Results of two clinical studies. Advances in Medical Psychotherapy, 10, 71–84.

- Park, C., Morrell, R. W., & Shifren, K. (Eds.). (1999). Processing of medical information in aging patients: Cognition and human factors perspectives Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Seckler, B., Meier, D. E., Mulvihill, M., & Cammer Paris, B. E. (1991). Substituted judgment: How accurate are proxy predictions?. Annals of Internal Medicine, 115, 92–98.

- Smyer, M., Schaie, K. W., & Kapp, M. B. (Eds.). (1996). Older adults’ decision making and the law New York: Springer. Zimny, G. H., & Grossberg, G. T. (1998). Guardianship of the elderly. New York: Springer.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.