This sample Anxiety and Optimal Athletic Performance Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Of all the psychological variables implicated in sport performance, anxiety is regarded to have the greatest impact. Putative explanations for why anxiety can degrade sport performance include diminished cognitive resources, a narrowing of the visual field, diminished motivation, and excessive muscle contraction or co-contraction of opposing muscle groups that impairs coordination or results in physical injury. As a consequence, a wide variety of techniques have been used to assist athletes in controlling or reducing anxiety. Yet in spite of the general consensus within the field of sport psychology that anxiety harms sport performance, there are major disputes as to which theory best describes this relationship and as to what the most appropriate means are to measure anxiety in athletes. This research paper presents an overview of anxiety and sport performance literature. Limitations of traditional theoretical explanations are described, as are more recent sport-specific theories based on the premise of individual differences in the responses of athletes, with particular emphasis on the Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning (IZOF) model.

Outline

- Introduction

- Traditional Theoretical Perspectives on the Anxiety– Performance Relationship

- Sport-Specific Theories of Anxiety and Performance

- Other Ideographic Theories

- Summary

1. Introduction

Anxiety has been defined as an emotion consisting of dysphoric thoughts, unpleasant sensations, and physical changes that occur in response to a situation or stimulus perceived to be threatening or dangerous. According to most theories, anxiety consists of state and trait components. State anxiety indicates the intensity of anxiety experienced at a given moment and can fluctuate widely in intensity over a short time span.

Trait anxiety is a more stable factor that assesses the general tendency of an individual to experience elevations in state anxiety when exposed to stressors such as sport competition. Persons scoring high in trait anxiety should experience greater increases in state anxiety when exposed to a stressor than should persons scoring low in trait anxiety. The experience of anxiety as a response to a stressor such as sport competition is contingent on both an individual’s perception of the stimulus and his or her ability to effectively cope with it. Because of this, sport competition may be perceived as threatening to some individuals, neutral to others, and enjoyable to still others.

1.1. Assessment of Anxiety

In sport psychology research, a variety of approaches have been used to quantify anxiety, including the observation of overt behavior, biological activity (e.g., galvanic skin activity, heart rate, stress hormones), and self-reports. No single method is entirely reliable. Assessments of behaviors implicated in anxiety (e.g., pacing) may be an anxiety-reducing strategy for some individuals or may be entirely unrelated to anxiety in other instances. Physiological variables that have been used as biological correlates of anxiety (e.g., electromyogram [EMG]) may be difficult to assess prior to competition, or they may provoke an increase in anxiety in some cases (e.g., sampling blood to assess stress hormones).

Because of these problems, anxiety is most commonly determined by means of self-report questionnaires. In sport research, the most frequently used general measure of anxiety has been the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a 40-item questionnaire that assesses both state and trait anxiety. Despite its proven validity, the efficacy of the STAI and other general measures of anxiety in the context of athletics has been questioned, leading to the creation of more than 30 sport-specific anxiety scales. Among these, the most widely used is the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory–2 (CSAI-2), a multidimensional anxiety measure that assesses self-confidence, somatic anxiety, and cognitive anxiety.

Despite advantages such as the ease of administration and interpretation, self-report measures are not without limitations. The validity and reliability of self-reports are delimited by verbal ability and self-awareness of emotional states. Administering questionnaires near the time of competition can be impractical or disruptive and might even result in increased anxiety by directing attention to internal emotional states. A more serious problem is response distortion, which occurs when individuals respond falsely to questionnaires for reasons such as social desirability, the demand characteristics of the experiment, and personal expectations. Response distortion can be detected through the use of lie scales, but this form of control is rarely used in sport psychology research.

2. Traditional Theoretical Perspectives On The Anxiety – Performance Relationship

It has been a long-standing belief in sport psychology that high levels of anxiety experienced during competition are harmful for performance and, if unabated, may even result in some athletes quitting their sport. A variety of interventions have been employed by sport psychology practitioners to reduce anxiety, including hypnosis, progressive relaxation, visualization, biofeedback, autogenic training, meditation, negative thought stopping, and confidence enhancement. However, it also has been posited that anxiety can facilitate performance under particular conditions. This perspective originally stemmed from drive theory, otherwise known as Hullian theory. According to Hullian theory, performance is a function of drive (i.e., physiological arousal or anxiety) and habit strength (i.e., skill). High levels of anxiety should increase the likelihood of correct behavior for well-learned skills, as would be the case for an emotional pep talk presented to a group of talented athletes. Evidence for drive theory in sport settings is lacking, however, and the theory currently has little status in the field of sport psychology.

Theoretical explanations in which high anxiety adversely influences performance have a higher standing in sport psychology, none more so than the Yerkes– Dodson law, familiarly known as the inverted-U hypothesis. The hypothesis stems from the classic work by Yerkes and Dodson, who in 1908 examined the influence of stimulus intensity on habit formation in experiments where mice were timed in maze running. Discrete levels of difficulty were created by manipulating the level of illumination of the maze and subjecting the mice to several intensities of stimulation via electrical shocks. The highest intensity shocks were found to slow learning under the most difficult (i.e., dimmest) maze trial, suggesting that moderate stimulation was best for such conditions. These results have since been widely reported in both general psychology and sport psychology textbooks, and they have been generalized to a number of constructs such as drive, motivation, learning, arousal, and anxiety.

In sport psychology, the hypothesis is presented as a relationship between athletic performance and either arousal or, more commonly, anxiety. Optimal performance should occur when anxiety is within a moderate range of intensity, whereas deviations above or below this range should result in progressively worsened performance. Hence, anxiety and performance exhibit a relationship describing the shape of an inverted U. In basic terms, optimal performance is most likely to occur when anxiety is neither too high nor too low, but because of the stressful nature of sport competition, it is assumed that it is far more likely for athletes to experience too much anxiety.

2.1. Sport Modifications

The inverted-U hypothesis has been adapted to account for sports with different physical requirements (e.g., fine motor skill vs gross motor skill) and the expertise of the athlete performing the task. Sport tasks that require precise motor control and minimal physical effort (e.g., putting in golf) are posited to benefit when anxiety or physiological arousal is low prior to and during the tasks. As tasks require greater physical effort but less fine motor control (e.g., tackling in football), progressively higher anxiety intensities should enhance performance. The second modification predicts that as expertise and talent in sport tasks increase, the optimal range of anxiety will also be higher compared with athletes who are either beginners or intermediate in skill. It is assumed that more talented athletes possess the necessary motor skills and coping strategies to harness higher anxiety, whereas less skilled or experienced individuals should exhibit worsened performance at the same anxiety intensity. Given information about sport and skill level for a given athlete, it should then be possible to establish an inverted-U function for the individual.

Despite the continued popularity of the inverted-U hypothesis, reviews of the literature in general psychology and sport psychology have concluded that its empirical support is weak or even entirely absent. It has been concluded that much of the research supporting the hypothesis has little bearing on sport because it was conducted in laboratory environments rather than realistic sport settings or because it used nonathletes as test participants. Studies of the inverted-U hypothesis have also failed to support the propositions that optimal anxiety is altered by the motor skills required for a sporting event or that comparably skilled athletes competing in the same sport benefit from similar anxiety levels.

Another concern expressed in reviews of the inverted-U hypothesis literature and other traditional theories is the assumption that arousal and anxiety are closely related or synonymous constructs. Arousal was originally defined as a global physiological response to a stressor that is closely associated with negative emotions such as anxiety. Subsequent research, however, has shown arousal to be a far more complex phenomenon. Standardized stressors evoke physiological responses that often exhibit little or no intercorrelation, and the pattern of physiological activation can vary considerably across individuals and situations. Physiological variables commonly employed as indicators of arousal (e.g., heart rate, respiration rate) are only weakly associated with self-report measures of anxiety, and this also is true for sport-specific measures of perceived arousal or somatic anxiety. Despite these findings, the conceptualization of arousal as an undifferentiated physiological response closely associated with anxiety persists, particularly within the field of sport psychology.

Finally, reviews of both the general and sport literature conclude that the inverted-U hypothesis and other traditional explanations indicate that athletes should respond uniformly to anxiety. They do not allow for the occurrence of interindividual differences to anxiety despite the fact that it has long been recognized that some athletes perform optimally under high intensities. In 1929, for example, the pioneering U.S. sport psychology researcher Coleman Griffith wrote, ‘‘Some of the most distressing cases of anxiety and fear in the dressing room have led to outstanding achievements during the game.’’

3. Sport-Specific Theories Of Anxiety And Performance

3.1. The IZOF Model

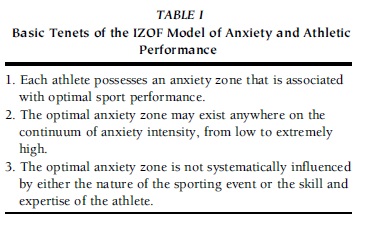

The lack of efficacy of traditional anxiety–performance theories, as well as the acknowledgment that individual differences contribute to this relationship, has spurred the development of sport-specific theories that incorporate this concept. Among these theoretical explanations, the Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning (IZOF) model is believed to have the strongest empirical basis. The IZOF model was developed by the Russian psychologist Yuri Hanin from studies of athletes in a wide variety of sports and competitive settings where anxiety was assessed using the Russian-language version of the STAI. The results of Hanin’s research supported an ideographic explanation, in which anxiety was associated with performance at the level of the individual athlete, rather than a nomothetic explanation, in which an entire team would respond similarly to anxiety. According to the IZOF model, each athlete possesses an optimal anxiety zone or range that is beneficial for performance. This optimal range may exist anywhere within the continuum of anxiety, from as low to as high as is measurable. When anxiety values fall outside the optimal zone, performance should decrease. The IZOF model further posits that the intensity of the optimal anxiety zone is not predictably influenced by either the type of sporting event or the skill of the individual athlete. As a result, an alternative method is needed to identify a more appropriate required anxiety level for an athlete than has been employed in traditional theories where the responses of athletes to anxiety are assumed to be more uniform (Table I).

TABLE I Basic Tenets of the IZOF Model of Anxiety and Athletic

TABLE I Basic Tenets of the IZOF Model of Anxiety and Athletic

3.2. Determining Optimal Anxiety

Two techniques have been developed to identify the optimal anxiety zone of an athlete: the direct method and the indirect method. For the direct method, state anxiety is assessed shortly before competitions until an athlete achieves a personal best performance. The optimal anxiety zone is then created by adding and subtracting 4 units to this anxiety score, which is approximately one-half standard deviation based on the STAI. The span of the optimal anxiety zone was established from initial research, but more recent studies have demonstrated that it can vary in width across athletes, indicating that some individuals can tolerate a wide range of anxiety intensity before experiencing a decline in performance. Unfortunately, the direct technique requires measuring anxiety prior to competitions until the athlete achieves an outstanding or personal best performance, a process that may require months or even years and that is compounded when dealing with large teams consisting of many athletes.

As a more efficient alternative, Hanin developed an indirect method based on retrospection of past competitions. With the indirect method, athletes complete the state portion of the STAI according to how they recall feeling prior to their own best past performances or prior to performances judged to be optimal. Again, 4 anxiety units are added and subtracted from this ‘‘recalled best’’ anxiety score to establish the optimal zone. The accuracy of the indirect method has been tested by correlating recalled anxiety scores with anxiety values actually obtained at the time of the recalled events, and effect sizes ranging from .60 to .80 have been reported consistently. Research indicates that the levels of accuracy in recalling anxiety are comparable in athletes who performed either better or worse than expected despite concerns that performance outcome could bias accuracy. Although the effect size for recalled and actual precompetition anxiety supports the use of the indirect method for determining optimal anxiety ranges, occasional reports of inaccurate recall have been noted in the literature. In such instances, the direct method should be used.

3.3. Interindividual Variability in Optimal Anxiety

The IZOF model predicts not only that athletes of a similar caliber in a given sport will differ in the intensity of optimal anxiety but also that a significant proportion will benefit from high anxiety. The findings from studies of athletes in a number of sports and different levels are consistent with these propositions, indicating that between 25 and 50% report that best performances occur when anxiety levels are elevated. As predicted by the IZOF model, the proportion of athletes who perform best at high anxiety intensities is not related to skill or even age. For example, in studies of elite U.S. distance runners, it was found that 30% of female runners reported that best performances were most likely when anxiety was significantly elevated, but percentages as high as 51% have been noted in nonelite college track and field athletes. Even in track and field athletes as young as 9 to 12 years, more than one in four indicated that they performed best with high anxiety. These results and other findings provide support for the IZOF model, but they are not consistent with group-based explanations of anxiety and performance. For example, according to both drive theory and the inverted-U hypothesis, the proportion of individuals who benefit from high anxiety should consistently be higher for elite athletes than for less talented competitors.

The evidence of wide-ranging variability in precompetition and optimal anxiety complicates the use of intervention strategies designed to regulate anxiety. Group-based interventions, in which an entire team of athletes receives a single treatment such as relaxation, are easily administered but would be ineffective or counterproductive for those athletes who perform best at moderate or high anxiety intensities. On the other hand, it can be time-consuming to use IZOF procedures to assess anxiety at the time of competition and then compare these values with each athlete’s optimal zone to determine who will be in need of some form of intervention.

3.4. Predicting Precompetition Anxiety

In an effort to provide a means for coaches and psychologists to efficiently identify those athletes who will require anxiety intervention, as well as to determine the appropriate direction of the intervention (e.g., increase or decrease anxiety), IZOF studies have tested the ability of athletes to anticipate the intensity they will experience prior to actual competition. In this research, athletes completed the state portion of the STAI several days prior to a competition with instructions to respond according to how they anticipated they would feel immediately before the competition. Athletes then completed the STAI again just before the competition under the standard instructional set (i.e., ‘‘right now’’), and that score was then compared with the predicted anxiety score. To minimize intrusiveness, the questionnaires were sometimes completed at a prescribed time before competition (e.g., 60 minutes). The results of this work reveal that predicted anxiety scores correlate quite closely with actual values. Correlations between predicted and actual precompetition anxiety range between .60 and .80, with higher coefficients occurring for difficult or important competitions.

Predicted precompetition anxiety scores are useful in situations where it would be difficult or impossible to assess anxiety just prior to the actual competition. The discrepancy between predicted precompetition anxiety and IZOF values can be contrasted to identify athletes who are likely to be too relaxed or too anxious, and this can be done several days before the competition.

From a practical perspective, the extent to which anxiety deviates from the optimal zone can help dictate how much anxiety must be increased or decreased to reach the optimal zone. Simple techniques that are easily implemented by the coaching staff can be an expeditious means to manipulate anxiety. These include emphasizing or deemphasizing the importance of the competition or the expectations of an athlete’s performance.

3.5. Impact of Optimal Anxiety on Performance

Research based on IZOF procedures indicates that deviations in precompetition anxiety from the optimal zone have a significant impact on performance. Studies of athletes in sports such as swimming, rhythmic gymnastics, and ice skating indicate that precompetition anxiety of successful performers is closer to their own optimal anxiety values than is the case with their less successful teammates. In most cases, performance differences are evident only in difficult competitions, and it has been speculated that optimal anxiety is not necessary to achieve adequate performance in easy or unimportant competitions. In research that has examined the net impact of anxiety on sport performance, it has been found that performances were approximately 2% worse on average in cases where precompetition anxiety fell outside the IZOF and that the decrement was approximately equal whether anxiety was lower or higher than optimal. Despite evidence that supports the major tenets of the IZOF model, the model has been criticized on a number of grounds. One primary concern is that the IZOF model does not indicate what variables contribute to the differences in optimal anxiety observed in homogenous groups of athletes. To date, studies of the factors contributing to interindividual variability in optimal anxiety have been rare, and the bulk of IZOF research has focused on examining the validity of the major tenets of the model. A second line of criticism contends that IZOF research based on the STAI or other nonspecific and general measures of anxiety is inadequate, whereas more complete results would be yielded by employing a sport-specific measure assessing multiple aspects of anxiety, particularly the CSAI-2. However, the results of CSAI-2 research on the IZOF model have been less consistent than research based on the STAI, and the IZOF model has been found to be less accurate than the STAI in assessing both recalled and predicted precompetition anxiety.

4. Other Ideographic Theories

Two other major theories of anxiety and sport performance have been adopted recently for sport: reversal theory and catastrophe theory. Although the concept of individual differences are not central to these theories, like the IZOF model, they acknowledge that anxiety can either facilitate or harm sport performance. Unlike the IZOF model, both reversal and catastrophe theories incorporate specific anxiety or perceived arousal scales. Reversal theory predicts that self-reported arousal is important to performance despite a lack of evidence that self-reports can provide an objective indication of physiological activity. Arousal is interpreted on the basis of an individual’s current emotional state that results from the interaction of oppositional high arousal preferring (paratelic) and low-arousal preferring (telic) states that are also assessed via self-reports. Catastrophe theory uses an arousal-related measure referred to as somatic anxiety, which is assumed to exhibit an inverted-U relationship with performance. In addition, measures of self-confidence and cognitive anxiety are assessed using a modified version of the CSAI-2 that assesses facilitative and debilitative anxiety. Cognitive anxiety is posited to be negatively related to performance, whereas self-confidence exhibits a positive relationship. When these dimensions are considered collectively, they form a complex three-dimensional figure referred to as a butterfly or catastrophe cusp. Reviews of the efficacy of reversal and catastrophe theories have been mixed, and this may stem in part from the challenges of validating these complex theories empirically.

5. Summary

The growing realization that traditional theoretical explanations of anxiety and performance fair poorly when applied to sport has led to the development of several models and theories of anxiety specific to athletes. Further research is needed before definitive judgments can be made about the relative efficacy of these theoretical explanations, but they all indicate that influence of anxiety on sport performance is more complex than is predicted by traditional explanations such as the inverted-U hypothesis. In particular, the results of IZOF model research reveal that the anxiety intensity associated with optimal sport performance varies considerably across athletes, even for those competing in the same competition. This research also indicates that a substantial percentage of athletes actually benefit from elevated anxiety and that in these cases, interventions aimed at reducing anxiety may be counterproductive.

Bibliography:

- Duffy, E. (1957). The psychological significance of the concept of ‘‘arousal’’ or ‘‘activation.’’ Psychological Review, 66, 183–201.

- Fazey, J., & Hardy, L. (1988). The inverted-U hypothesis: A catastrophe for sport psychology? Leeds, UK: White Line Press.

- Griffith, C. R. (1929). The psychology of coaching. New York: Scribner.

- Hackfort, , & Schwenkmezger, P. (1993). Anxiety. In R. M. Singer, M. Murphey, & L. K. Tennant (Eds.), Handbook of research on sport psychology (pp. 328–364). New York: Macmillan.

- Hackfort, D., & Spielberger, C. D. (Eds.). (1989). Anxiety in sports. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Hanin, Y. L. (Ed.). (2000). Emotion in sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior. New York: Appleton. Martens, R., Vealey, R. S., & Burton, D. (1990). Competitive anxiety in sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Neiss, R. (1988). Reconceptualizing arousal: Psychobiological states in motor Psychological Bulletin, 103, 345–366.

- Ostrow, A. C. (1996). Directory of psychological tests in the sport and exercise sciences (2nd ). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Oxendine, J. B. (1970). Emotional arousal and motor performance. Quest, 13, 23–32.

- Raglin, J. S., & Hanin, Y. L. (2000). Competitive In Y. L. Hanin (Ed.), Emotion in sports (pp. 93–111). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Raglin, S. (1992). Anxiety and sport performance. In J. O. Holloszy (Ed.), Exercise and sport sciences reviews (Vol. 20, pp. 243–274). New York: Williams & Wilkins.

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L, Lushene, R. E., Vagg, P. R, & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.