This sample Applied Behavior Analysis Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

On any given night, the evening news depicts countless societal problems. Traffic crashes, epidemics such as HIV and obesity, medical errors, violence and drugs in schools, interpersonal conflict, and global warming pose significant economic consequences, as well as devastating costs in terms of human suffering and loss of life. Human behavior contributes to each of these societal problems, but human behavior can also be a critical part of the solution. For more than 50 years, applied behavior analysts have studied people in an attempt to increase their desirable behaviors and decrease their undesirable behaviors.

The Association for Behavior Analysis International, founded in 1974, promotes the experimental, theoretical, and applied analysis of behavior in order to benefit human welfare. It provides a forum for 23 special-interest groups, and maintains a mutually beneficial relationship with 60 affiliated chapters around the world. The 14 different program areas for this organization’s annual professional convention illustrate the diverse areas of research and application for behavior analysis (Association for Behavior Analysis International, 2007).

Specifically, the research papers, symposia, and tutorials at the annual Association for Behavior Analysis International convention are organized into the following domains: (a) autism; (b) behavioral pharmacology; (c) clinical, family, and behavioral medicine; (d) community interventions and social and ethical issues; (e) developmental disabilities; (f) human development and gerontology; (g) experimental analysis of behavior; (h) education; (i) international track (translated into Spanish); (j) organizational behavior management; (k) teaching behavior analysis; (l) theoretical, philosophical, and conceptual issues; (m) verbal behavior; and (n) other.

Each of these topic areas includes an experimental (i.e., experimental behavior analysis) and an applied (i.e., applied behavior analysis) component. This research-paper focuses on applied behavior analysis (ABA), or the application of behavior analysis principles and methods to improve behavior. Although each of the topic areas listed above includes behavioral targets for ABA, this research-paper focuses on the applications of ABA to address large-scale societal issues, especially industrial and transportation safety and environment protection. First, however, we cover the basic principles of all ABA interventions, all of which are relevant for each problem domain.

Principles of Applied Behavior Analysis

Effective applications of ABA generally follow the seven key principles now described. Each principle is broad enough to include a wide range of practical operations, but narrow enough to define the ABA approach to managing behaviors relevant for promoting human welfare (e.g., safety, health, work productivity, and parenting). I have proposed these principles in several sources, as a map or mission statement against which to check interventions designed to improve behaviors and attitudes in organizations, homes, neighborhoods, and throughout the community (Geller, 2001, 2005; Geller & Johnson, 2007).

1. Target Observable Behavior

The ABA approach is founded on behavioral science as conceptualized and researched by B. F. Skinner (1938). Experimental behavior analysis, and later ABA, emerged from Skinner’s research and teaching, and laid the groundwork for numerous therapies and interventions to improve the quality of life among individuals, groups, and entire communities (Greene, Winett, Van Houten, Geller, & Iwata, 1987). Whether working one-on-one in a clinical setting or with work teams throughout an organization, the intervention procedures always target specific behaviors in order to promote constructive change. ABA focuses on what people do, analyzes why they do it, and then applies an evidence-based intervention strategy to improve what people do.

The focus is on acting people into thinking differently rather than targeting internal awareness, intentions, or attitudes in order to think people into acting differently. This latter approach is used successfully by many clinical psychologists in professional therapy sessions, but is not cost-effective in group, organizational, or community-wide settings. To be effective, thinking-focused intervention requires extensive one-on-one interaction between a client and a specially trained intervention specialist.

Even if time and facilities were available for interventions to focus on internal and nonobservable person states, few intervention agents in the real world (e.g., teachers, parents, coaches, health-care workers, and safety professionals) possess the educational background, training, and experience to implement such an approach. A basic tenet of ABA is that interventions should occur at the natural site of the behavioral issue (e.g., corporation, school, home, or athletic field) and be administered by an indigenous change agent (e.g., work supervisor, teacher, parent, or coach).

2. Focus on External Factors to Explain and Improve Behavior

Skinner did not deny the existence of internal determinants of behavior (such as personality characteristics, perceptions, attitudes, and values). He only rejected such unobservable inferred constructs for scientific study as causes or outcomes of behavior. We obviously do what we do because of factors in both our external and internal worlds. However, given the difficulty in objectively defining internal traits or states, it is more cost effective to identify environmental conditions that influence behavior and to change these factors when behavior change is necessary.

Examining external factors to explain and improve behavior is a primary focus of organizational behavior management (Gilbert, 1978). Organizational behavior management uses ABA principles to develop interventions to improve work quality, productivity, and safety. The ABA approach to occupational safety is termed “behavior-based safety” and is currently used worldwide to increase safety-related behaviors, decrease at-risk behaviors, and thereby prevent workplace injuries (e.g., Geller, 2001; McSween, 2003). Recently, the ABA approach to organizational safety has been customized for application in health-care facilities in order to prevent medical error and improve patient safety (Geller & Johnson, 2007).

The pertinent point here is that ABA focuses on the external environmental conditions and contingencies influencing a target behavior. Before deciding on an intervention approach, a careful analysis is conducted of the situation, the target behavior, and the individual(s) involved in any observed discrepancy between the behavior observed and the behavior desired (i.e., real vs. ideal behavior). If the gap between the actual and the desired behavior warrants change, a behavior-focused intervention is designed and implemented with adherence to the next three principles.

3. Direct with Activators and Motivate with Consequences

This principle enables understanding of why behavior occurs, and guides the design of interventions to improve behavior. It runs counter to common sense or “pop psychology.” When people are asked why they did something, they offer statements such as “Because I wanted to do it,” “Because I needed to do it,” or “Because I was told to do it.” These explanations sound as if the cause of behavior precedes it. This perspective is generally supported by a multitude of “pop psychology” self-help books and audiotapes that claim we motivate our behavior with self-affirmations, positive thinking, optimistic expectations, or enthusiastic intentions.

The fact is, however, we do what we do because of the consequences we expect for doing it. As Dale Carnegie (1936) put it, “Every act you have ever performed since the day you were born was performed because you wanted something” (p. 62).

Activators (or signals preceding behavior) are only as powerful as the consequences supporting them. In other words, activators tell us what to do in order to receive a consequence, from the ringing of a telephone or doorbell to the instructions from a training seminar or one-on-one coaching session. We follow through with the particular behavior activated (from answering a telephone to following a trainer’s instructions) to the extent we expect doing so will give us a pleasant consequence or enable us to avoid an unpleasant consequence.

This principle is typically referred to as the ABC model or three-term contingency, with A for activator (or antecedent), B for behavior, and C for consequence. Applied behavior analysts use this ABC principle to design interventions for improving behavior at individual, group, and organizational levels. More than 50 years of behavioral science research has demonstrated the efficacy of this general approach to directing and motivating behavior change. The ABC (activator – behavior – consequence) contingency is illustrated in Figure 98.1.

Figure 98.1 Operant and respondent conditioning can occur simultaneously.

Figure 98.1 Operant and respondent conditioning can occur simultaneously.

The dog will move if he expects to receive food after hearing the sound of the can opener. The direction provided by an activator is likely to be followed when it is backed by a soon, certain, and significant consequence. This process is termed operant, or instrumental, conditioning. The consequence is a positive reinforcer when behavior is emitted to obtain it. When behavior occurs to avoid or escape a consequence, the consequence is a negative reinforcer.

If the sound of the can opener elicits a salivation reflex in the dog, we have an example of classical, or respondent, conditioning. In this case, the can-opener sound is a conditioned stimulus (CS) and the salivation is a conditioned response (CR). The food that follows the sound of the electric can opener is the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), which elicits the unconditioned response (UCR) of salivating without any prior learning experience. This UCS – UCR reflex is natural, or “wired in” the organism.

Perhaps you recall this terminology from a basic learning course in psychology. We review it here because ABA is founded on these learning principles, especially operant conditioning, whereby people choose behavior in order to obtain a pleasant consequence or to escape or avoid an unpleasant consequence. But as shown in Figure 98.1, operant (instrumental) and respondent (classical) conditioning often occur simultaneously. Although we operate on the environment to achieve a desirable consequence or avoid an undesirable consequence, emotional reactions are often classically conditioned to specific stimulus events in the situation. We learn to like or dislike the environmental context and/or the people involved in administrating the ABC contingency, which is how the type of behavioral consequence influences attitudes, and why ABA interventions feature positive consequences.

4. FOCUS on Positive consequences to Motivate Behavior

Skinner’s (1971) concern for people’s feelings and attitudes is reflected in his antipathy toward the use of punishment (or negative consequences) to motivate behavior. “The problem is to free men, not from control, but from certain kinds of control” (p. 41). He goes on to explain why control by negative consequences must be reduced in order to increase perceptions of personal freedom.

To be sure, the same situation can be viewed as control by punishment of unwanted behavior or control by positive reinforcement of desired behavior. Some of the students in my university classes, for example, are motivated to avoid failure (e.g., a poor grade), whereas other students are motivated to achieve success (e.g., a good grade or even increased knowledge). Which of these groups of students feel more empowered and in control of their class grade, and thus have a better attitude toward my classes? Of course, you know the answer to this question because you can reflect on your own feelings or attitude in similar situations where you perceived your behavior as influenced by positive or negative consequences.

Achieving Success Versus Avoiding Failure

Years ago, Atkinson and his associates (1957) compared the decision making of individuals with a high need to avoid failure and that of those with a high need to achieve success, and found dramatic differences. Although those participants motivated to achieve positive consequences set challenging but attainable goals, those participants with a high need to avoid failure were apt to set goals that were either overly easy or overly difficult.

The setting of easy goals assures avoidance of failure, while setting unrealistic goals provides a readily available excuse for failure—termed self-handicapping by more recent researchers (Rhodewalt, 1994). Thus, a substantial amount of behavioral research and motivational theory justifies the advocacy of positive reinforcement over punishment contingencies, whether contrived to improve someone else’s behavior or imagined to motivate personal rule-governed behavior (see Wiegand & Geller, 2005).

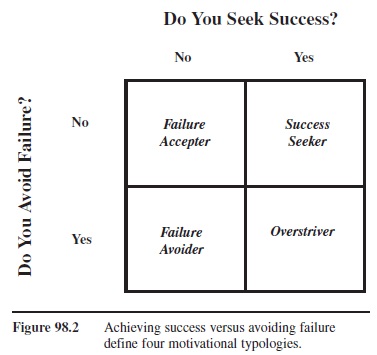

Figure 98.2 depicts four distinct motivational typologies initially defined by Covington and Omelich (1991). These four classifications have been the focus of research attempting to explain differences in how people approach success and/or avoid failure. It is most desirable to be a success seeker. These individuals are optimists, responding to setbacks (e.g., corrective feedback) in a positive and adaptive manner. They display “exemplary achievement behaviors” in that they are self-confident and willing to take risks, as opposed to avoiding challenges in order to avoid failure.

Figure 98.2 Achieving success versus avoiding failure define four motivational typologies.

Figure 98.2 Achieving success versus avoiding failure define four motivational typologies.

Overstrivers are diligent, successful, meticulous, and at times optimistic. However, they have self-doubt about their abilities and experience substantial evaluation anxiety, driving them to avoid failure by working hard to succeed. They are preoccupied with perfection, often over-preparing for a challenge (Covington, 1992).

Failure avoiders have a low expectancy for success and a high fear of failure. Therefore, they do whatever it takes to protect themselves from implications they are incompetent. They often use self-handicapping and defensive pessimism to protect themselves from potential failure (Covington, 1992). These individuals are motivated but are not “happy campers.”

Finally, the failure accepters are low in both expectancy for success and fear of failure. They merely accept their failure as an indication of low ability. Unlike the failure avoiders, however, these individuals are not worried about failure or their inability to succeed. They have merely given up, displaying behavior analogous to learned helplessness (Maier & Seligman, 1976).

Personality Traits Versus States

Much of the research literature addressing these four motivational typologies seems to imply they reflect relatively stable and persistent qualities of individuals. They represent personality traits rather than states (Wiegand & Geller, 2005). However, other researchers and practitioners, especially proponents of ABA, view these characteristics as fluctuating states under the influence of the environment and antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) contingencies. The environmental conditions and contingencies set the stage for success seeking, overstriving, failure avoiding, or failure accepting. The results or consequences of one’s efforts can maintain or change one’s perspective.

Success seeking is cultivated through positive reinforcement, while overstriving and failure avoiding result from negative reinforcement and punishment. After consistent failure, an individual might simply give up and become a failure accepter. These individuals are not motivated to even try a challenging task. Wouldn’t you rather have a failure avoider or overstriver on your team, and attempt to move their state toward success seeking?

The Contingency for Success Seeking

The ABA approach to promoting success seeking is to apply positive reinforcement contingencies strategically instead of negative reinforcement or punishment. However, punishment contingencies are relatively easy to implement on a large scale. That’s why the government selects this approach to behavior management. Just pass a law and enforce it. And when monetary fines are paid for transgressions, the controlling agency obtains financial support for continuing its enforcement efforts.

In many areas of large-scale behavior management, including transportation safety, control by negative consequences is seemingly the only feasible approach. As a result, the side effects of aggressive driving and road rage are relatively common and observed by anyone who drives. Most of us have experienced the unpleasant emotional reactions of seeing the flashing blue light of a police vehicle in our rearview mirror—another example of classical conditioning. Also, you’ve probably witnessed the temporary impact of this enforcement threat. Classic research in experimental behavior analysis taught us to expect only temporary suppression of a punished behavior (Azrin & Holz, 1966), and to predict that some drivers in their “Skinner box on wheels” will drive faster to compensate for the time they lost when slowing down in an “enforcement zone” (Estes & Skinner, 1941).

Practical ways to apply positive reinforcement contingencies to driving are available (Geller, Kalsher, Rudd, & Lehman, 1989; Hagenzieker, 1991), but much more long-term research is needed in this domain. Various positive reinforcement contingencies need to be applied and evaluated with regard to their ability to offset the negative side effects of the existing negative reinforcement contingencies.

Regardless of the situation, managers, teachers, or work supervisors can often intervene to increase people’s perceptions they are working to achieve success rather than working to avoid failure. Even our verbal behavior directed toward another person, perhaps as a statement of genuine approval or appreciation for a task well done, can influence motivation in ways that increase perceptions of personal freedom and empowerment. However, words of approval are not as common as words of disapproval. Thus, although ABA change agents focus their intervention on observable behavior, they are concerned about attitude, as reflected in the next principle.

5. Design Interventions with Consideration of Internal Feelings and Attitudes

Skinner was certainly concerned about unobservable attitudes or feeling states, which is evidenced by his criticism of punishment because of its impact on people’s feelings or perceptions. This perspective also reflects a realization that intervention procedures influence feeling states, which can be pleasant or unpleasant, desirable or undesirable. Internal feelings or attitudes are influenced indirectly by the type of behavior-focused intervention procedure implemented, and such relationships require careful consideration by the developers and managers of a behavior-change process.

The rationale for using more positive than negative consequences to motivate behavior is based on the differential feeling states provoked by positive reinforcement versus punishment procedures. Similarly, the way we implement an intervention process can increase or decrease feelings of empowerment, build or destroy trust, and cultivate or inhibit a sense of teamwork or belonging (Geller, 2001, 2005). Thus, it is important to assess feeling states or perceptions occurring concomitantly with an intervention process. Such assessment can be accomplished informally through one-on-one interviews and group discussions, or formally with a perception survey (O’Brien, 2000).

Social Validity

Hence, decisions regarding which ABA intervention to implement and how to refine existing intervention procedures should be based on both objective behavioral observations and subjective evaluations of feeling states. Often, it’s possible to evaluate the indirect internal impact of an intervention by imagining oneself going through a particular set of intervention procedures and asking the question “How would I feel?” However, ABA researchers and practitioners advocate a more comprehensive and systematic approach, termed assessment of social validity.

Social validity assessment includes the use of rating scales, interviews, and focus-group discussions to assess (a) the societal significance of the intervention goals, (b) the social appropriateness of the procedures, and (c) the societal importance or clinical significance of the intervention effects (Geller, 1991).

The Four Components of ABA Intervention

A comprehensive social validity evaluation addresses the four basic components of an ABA intervention process: selection, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination. Selection refers to the importance or priority of the behavioral problem and the population targeted for change. Addressing the large-scale problems of transportation safety, global warming, prison management, identity theft, child abuse, and medical errors is clearly important, but given limited resources, which issue should receive priority? The answer to this question depends partly on the availability of a cost-effective intervention.

Assessing the social validity of the implementation stage of ABA intervention includes evaluating the behavior-change goals and procedures of the behavior-change process. How acceptable is the plan to potential participants and other parties, even those tangentially associated with the intervention? In the case of an industrial safety program, for example, answering this question entails obtaining acceptability ratings not only from company employees but also from the employees’ family members and the customers of the company. Are the intervention procedures consistent with the organization’s values and mission statement, and do they reach the most appropriate audience?

The social validity of the evaluation stage refers, of course, to the impact of the intervention process, which includes estimates of the costs and benefits of an intervention as well as measures of participant or consumer satisfaction. The numbers or scores obtained from various measurement devices (e.g., environmental audits, behavioral checklists, interview forms, output records, and attitude questionnaires) need to be reliable and valid. They also need to be understood by the people who use them. If they are not, the evaluation scheme does not provide useful feedback and cannot lead to continuous improvement.

Meaningless or misunderstood evaluation numbers also limit the dissemination potential and large-scale application of an intervention. Now we’re talking about the social validity of the dissemination stage of the ABA intervention process, which is the weakest aspect of ABA intervention, and perhaps of applied psychology in general. More specifically, intervention researchers and scholars justify their efforts and obtain financial support based on the scientific rigor of their methods and the statistical significance of their results. Rarely do these scholars address the real-world dissemination challenges of their findings.

Unfortunately, dissemination and marketability are left to corporations, consulting firms, and “pop psychologists.” As a result, there are often disconnects between the science of ABA (and other psychological processes) and behavior-change intervention in the real world. One solution to this dilemma is to teach the real-world users of a behavior-change process how to conduct their own evaluations of intervention impact, which brings us to the next ABA principle.

6. Apply the Scientific Method to Improve Intervention

Some people believe dealing with the human dynamics of behavior change requires only “good common sense.” However, you surely realize the absurdity of such a premise. Common sense is based on people’s selective listening and interpretation, and is usually founded on what sounds good to the individual listener, not necessarily on what works. In contrast, systematic and scientific observation enables the kind of objective feedback needed to know what works and what doesn’t work to improve behavior.

The occurrence of specific behaviors can be objectively observed and measured before and after the implementation of an intervention process. This application of the scientific method provides feedback with which behavioral improvement can be shaped. To teach this principle of ABA to change agents (e.g., coaches, teachers, parents, work supervisors, and hourly workers) who are empowered to improve the behavior of others and want to improve their intervention skills, I use the acronym “DO IT”—Define, Observe, Intervene, and Test. This process represents the scientific method ABA practitioners have used for decades to demonstrate the impact of a particular behavior-change technique (cf. Geller, 2001, 2005).

“D” for Define

The process begins by defining specific behaviors to target, which are undesirable behaviors that need to decrease in frequency and/or desirable behaviors that need to occur more often. Avoiding certain unwanted behaviors often requires the occurrence of alternative behaviors, and therefore an intervention target might be behavior to substitute for particular undesirable behavior. On the other hand, a desirable target behavior can be defined independently of undesired behavior. For example, a safety-related target might be as basic as using certain personal protective equipment (PPE) or “walking within pedestrian walkways.” Or, the safe target could be a process requiring a particular sequence of safe behaviors, as when lifting a heavy object or locking out an energy source.

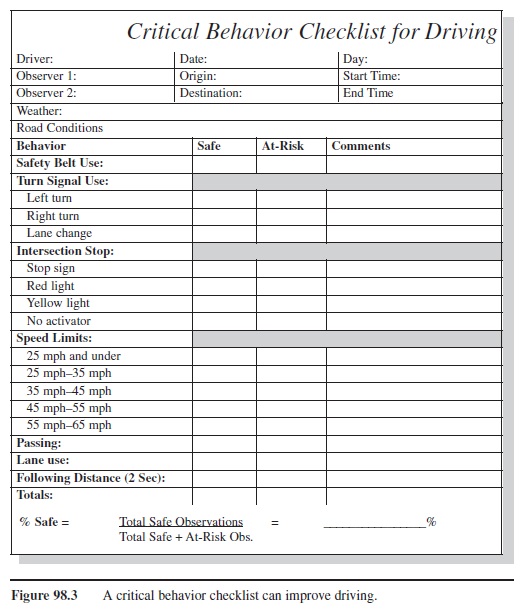

Defining and evaluating ongoing behavior is facilitated with the development of a behavioral checklist to use during observations. The development of such behavioral definitions enables an invaluable learning experience. When people get involved in deriving a behavioral checklist, they own a training process that can improve human dynamics on both the outside (behaviors) and the inside (feelings and attitudes) of people.

“O” for Observe

When people observe one another for certain desirable or undesirable behaviors, they realize everyone performs undesirable behavior, sometimes without even realizing it. The observation stage is not a fault-finding procedure; it is a fact-finding learning process to facilitate the discovery of behaviors and conditions that need to be changed or continued in order to be competent at a task. Thus, no behavioral observation need be made without awareness and explicit permission from the person being observed. Observers should be open to learning as much (if not more) from the process as they expect to teach from completing the behavioral checklist.

There is not one generic observation procedure for every situation, and the customization and refinement of a process for a particular setting never stops. It is often beneficial to begin the observation process with a limited number of behaviors and a relatively simple checklist, which reduces the possibility of people feeling overwhelmed in the beginning. Starting small also enables the broadest range of voluntary participation, and provides numerous opportunities to improve the process successively by expanding coverage of both behaviors and work areas. Details on how to design and use a critical behavior checklist (CBC) for constructive observation and feedback are given in several texts (e.g., Geller, 2001, 2005; McSween, 2003).

The critical behavior checklist for driving. I used the CBC depicted in Figure 98.3 to teach my daughter safe driving practices. She was 15 years old and thought the “driver’s ed program” she had in high school was sufficient. I knew better. We needed to develop and apply a CBC. Through one-on-one discussion, Krista and I derived a list of critical driving behaviors and then agreed on specific definitions for each item. My university students practiced using this CBC a few times with various drivers, resulting in a refined list of behavioral definitions.

After discussing the revised list of behaviors and their definitions with Krista, I felt ready to implement the second stage of DO IT—observation. I asked my daughter to drive me to the university—about nine miles from home—to pick up some papers. I overtly recorded observations on the CBC during both legs of this roundtrip. When returning home, I totaled the safe and at-risk checkmarks and calculated the percentage of safe behaviors. Her percentage of safe driving was 85 percent, and I considered this quite good for our first time. (Note my emphasis on achieving safe rather than avoiding at risk.)

I told Krista her “percent safe” score and proceeded to show her the list of safe checkmarks, while covering the few checks in the at-risk column. To my surprise, she did not seem impressed with her percent-safe score. Rather, she pushed me to tell her what she did wrong. “Get to the bottom line, Dad,” she asserted. “Where did I screw up?”

This initial experience with the CBC for driving was enlightening in two aspects. First, it illustrated the unfortunate reality that the “bottom line” for many people is “Where did I go wrong?” My daughter, at age 15, had already learned that people evaluating her performance seem to be more interested in mistakes than successes. This perspective activates failure avoiding over success seeking, an undesirable influence, as discussed above.

A second important outcome from this CBC experience was the realization that people can be unaware of their at-risk behavior, and only through objective behavior-based feedback can it be changed. Krista did not readily accept my corrective feedback regarding her four at-risk behaviors. In fact, she emphatically denied she did not always come to a complete stop at intersections with stop signs. However, she was soon convinced of her error when I showed her my data sheet and my comments regarding the particular intersection where there was no traffic and she made only a rolling stop before turning right.

Figure 98.3 A critical behavior checklist can improve driving.

Figure 98.3 A critical behavior checklist can improve driving.

Of course, I reminded Krista she used her turn signal at every intersection, and she should be proud of that behavior. I wanted to make this behavior-based coaching process a positive, success-seeking experience, so it was necessary to emphasize the behaviors I observed her do correctly. Obviously, we are now in the intervention phase of DO IT, with interpersonal feedback being the ABA intervention tactic.

“I” for Intervene

During this stage, interventions are designed and implemented in an attempt to increase desired behavior and/or decrease undesired behavior. As reflected in Principle 2, intervention means changing external conditions of the behavioral context or system in order to make desirable behavior more likely than undesirable behavior. When designing interventions, Principles 3 and 4 are critical: The most motivating consequences are soon, certain, and sizable (Principle 3), and positive consequences are preferable to negative consequences (Principle 4).

The process of observing and recording the frequency of desirable and undesirable behavior on a checklist provides an opportunity to give individuals and groups valuable behavior-based feedback. When the results of a behavioral observation are shown to individuals or groups, they receive the kind of information that enables practice to improve performance. Considerable research has shown that providing people with feedback regarding their ongoing behavior is a very cost-effective intervention approach. (See, for example, the comprehensive reviews of behavior-based feedback by Alvero, Bucklin, & Austin, 2001.)

The real Hawthorne Effect. The classic Hawthorne Effect is characterized as demonstrating people change their behavior in desired directions when they know their behavior is being observed (Whitehead, 1938). The fact is, however, the Hawthorne Effect was not due to observation but to feedback. Parsons (1974) conducted a careful reexamination of the Hawthorne data (originally obtained at the Western Electric plant in the Hawthorne community near Chicago) and interviewed eyewitness observers, including one of the five female relay assemblers who were the primary targets of the Hawthorne studies.

During the intervention phase, the five women observed systematically in the Relay Assembly Test Room received regular feedback about the number of relays each had assembled. Feedback was especially important to these workers because their salaries were influenced by an individual piecework schedule—the more relays each employee assembled, the more money each earned.

In addition to behavioral feedback, researchers have found many other intervention strategies to be effective at increasing desirable work practices, including worker-designed behavioral prompts, individual reporting of personal errors, behavior-change promise cards, individual and group goal setting, behavior-based thank-you cards, individual and group recognition events, as well as incentive/reward programs for individuals or groups (see Geller, 2001, and McSween, 2003, for procedural details and implementation results).

“T” for Test

The test phase of DO IT provides work teams or change agents with the information they need to refine or replace an ABA intervention, and thereby improve the process. If observations indicate significant improvement in the target behavior has not occurred, the change agents analyze and discuss the situation, and refine the intervention or choose another intervention approach. On the other hand, if the target reaches the desired frequency level, the change agents can turn their attention to another set of behaviors. They might add new critical behaviors to their checklist, thus expanding the domain of their behavioral observations. Alternatively, they might design a new intervention procedure to focus only on the new behaviors.

Every time the participants evaluate an intervention approach, they learn more about how to improve the targeted behaviors. They have essentially become behavioral scientists, using the DO IT process to (a) diagnose a problem involving human behavior, (b) monitor the impact of a behavior-change intervention, and (c) refine interventions for continuous improvement. The results from such testing provide motivating consequences to support this learning process and keep the change agents and their participants involved.

7. Use Theory to Integrate Information, Not to limit Possibilities

Although much, if not most, research is theory driven, Skinner (1950) was critical of designing research projects to test theory. Theory-driven research can narrow the perspective of the investigator and limit the extent of findings from the scientific method. Thus, applying the DO IT process merely to test a theory can be like putting blinders on a horse: It can limit the amount of information gained from systematic observation.

Many important findings in ABA have resulted from exploratory investigation. That is, systematic observations of behavior occurred before and after an intervention or treatment procedure to answer the question “I wonder what will happen if…?” rather than “Is my theory correct?” In these situations, ABA researchers were not expecting a particular result, but were open to finding anything. Subsequently, they modified their research design or observation process according to their behavioral observations, not a particular theory. Their innovative research was data driven rather than theory driven, which is an important perspective for behavior-change agents, especially when applying the DO IT process.

It is often better to be open to many possibilities for improving performance than to be motivated to support a certain process. Numerous intervention procedures are consistent with the ABA approach, and an intervention process that works well in one situation will not necessarily be effective in another setting. Thus, it is usually advantageous to teach change agents to make an educated guess about what intervention procedure to use at the start of a behavior-change process, while being open to intervention refinement as a result of the DO IT process. Of course, Principles 1 to 4 should always be used as guidelines when designing intervention procedures.

After many systematic applications of the DO IT process, distinct consistencies will be observed. Certain procedures will work better in some situations than others, with some individuals than others, or with some behaviors than others. Summarizing functional relationships between intervention impact and specific situational or interpersonal characteristics can lead to the development of a research-based theory of what works best under particular circumstances. Thus, theory might be used to integrate information gained from systematic behavioral observation. Skinner (1950) approved of this use of theory, but cautioned that premature theory development can lead to premature theory testing and limited profound knowledge.

Examples Of Applied Behavior Analysis Intervention

Most large-scale ABA interventions designed to improve behavior can be classified as either antecedent or consequence strategies. This section reviews four activator (or antecedent) strategies and three consequence strategies that ABA change agents have applied effectively to change socially important behaviors. The success of these ABA interventions was evaluated with a DO IT scheme, as previously discussed.

Activators

Activators or antecedent interventions include (a) education, (b) verbal and written prompts, (c) modeling and demonstrations, and (d) commitment procedures.

Education

Before attempting to improve a behavior, it is often important to provide a strong rationale for the requested change. Sometimes this process involves making remote, uncertain, or unknown consequences more salient to the relevant audience. For example, an intervention designed to increase recycling could provide information about (a) the negative consequences of throwing aluminum cans in the trash (e.g., wasted resources, unnecessary energy consumption, and overflowing landfills), as well as (b) the positive consequences associated with recycling behavior (e.g., energy savings, decreased pollution, reduced use of landfill space).

Educational antecedents can be disseminated through print or electronic media, or delivered personally in individual or group settings. Researchers have shown that education presented interpersonally is more effective when it is done in small rather than large groups and when it actively involves participants in relevant activities and demonstrations (e. g., Lewin, 1958). However, although providing information and activating awareness of a problem are often important components of ABA intervention, information alone is seldom sufficient to change behavior, especially when the desired behavior is inconvenient. Thus, education or awareness antecedents are often combined with other intervention components, as are now discussed.

Prompts

Prompting strategies are verbal or written messages strategically delivered to promote the occurrence of a target behavior. Such activators serve as reminders to perform the target behaviors. Geller, Winett, and Everett (1982) identified several conditions under which prompting antecedents are most effective: (a) the target behavior is specifically defined by the prompt (e.g., “Buckle your safety belt” rather than “Drive safely”), (b) the target behavior is relatively easy to perform (e.g., using a designated trash receptacle vs. collecting and delivering recyclables), (c) the message is displayed where the target behavior can be performed (e.g., at the store where “green” commodities are sold vs. on the local news), and (d) when the message is stated politely (e.g., “Please buckle up” vs. “You must buckle up”).

Actually, rude or overly demanding messages can backfire and result in individuals doing the opposite of what the prompt demands or looking for ways to assert their individual freedom when a prompt is viewed as irrational or unfair. This tendency to rebel against a top-down request was termed countercontrol by Skinner (1971) and psychological reactance by social psychologist Brehm (1966).

Prompts are popular because they (a) are simple to implement, (b) cost relatively little, and (c) can have considerable impact if used properly. For example, Werner, Rhodes, and Partain (1998) increased dramatically the amount of polystyrene recycling in a university cafeteria by increasing the size of signs designed to prompt recycling and placing them next to recycling bins. Also, Geller, Kalsher, Rudd, and Lehman (1989) designed safety-belt reminders to be hung from the rearview mirrors of personal vehicles. In both of these successful applications, the prompts were displayed in close proximity to where the target behavior could be emitted, and the behavior requested was relatively convenient to perform.

Modeling

Although prompts can be effective for simple, convenient behaviors, modeling is a more appropriate approach when the desired behavior is complex. Modeling involves demonstrating specific target behaviors to a relevant audience. This activator is more effective when the model receives a rewarding consequence immediately after the target behavior is performed (Bandura, 1977). Modeling can be accomplished via an interpersonal demonstration, but reaches a broader audience through electronic media.

Research by Winett, Leckliter, Chinn, Stahl, and Love (1985) exemplifies a large-scale modeling intervention to increase energy conservation behaviors. Those participants who viewed a 20-minute videotaped presentation of relevant conservation behaviors significantly decreased their residential energy use over a 9-week period. It’s noteworthy that the video specified the positive financial consequences of performing the conservation behaviors.

Behavioral Commitment

Behavioral commitment is straightforward and easy to implement, and it can be highly effective. Although all ABA interventions request behavior change, a behavioral commitment takes this process a step further by asking individuals to agree formally to change their behavior. In other words, they make a behavioral commitment. Intervention researchers have shown reliably that asking individuals to make a written or verbal commitment to perform a target behavior increases the likelihood that behavior will be performed (e.g., see review by Dwyer, Leeming, Cobern, Porter, & Jackson, 1993).

When individuals sign a pledge or promise card to increase a desirable behavior (e.g., buckle-up, recycle, exercise) or cease an undesirable behavior (e.g., drive while impaired, smoke cigarettes, litter) they feel obligated to honor their commitment, and often do. ABA professionals explain commitment-compliant behavior with the notion of rule-governed behavior. People learn rules for behavior and through experience learn that following the rule is linked to positive social and personal consequences (e.g., interpersonal approval), and breaking the rule can lead to the negative consequences of disapproval or legal penalties (Geller, 2001). Social psychologists attribute this tendency to follow through on a behavioral commitment to the social norm of consistency, which creates pressure to be internally and externally consistent (Cialdini, 2001).

This behavioral commitment strategy can be conveniently added to many ABA interventions. For example, at a time when vehicle safety-belt use was not the norm, Geller et al. (1989) combined commitment and prompting strategies by asking university students, faculty, and staff to sign a card promising to use their vehicle safety belts. Many participants hung the “promise card” on the rearview mirror of their vehicles, which served as a proximal prompt to buckle up. As you may have guessed, individuals who signed the “Buckle-Up Promise Card” were already using their vehicle safety belt more often than those individuals who did not. However, after signing the pledge, these individuals increased their belt use significantly (Geller et al., 1989).

Consequence Strategies

ABA researchers and practitioners consider consequences to be the primary determinant of voluntary behavior. In fact, the most effective activators make recipients aware of potential consequences, either explicitly or implicitly. Let’s consider three basic consequence strategies: penalties, rewards, and feedback.

Penalties

These interventions identify undesirable behaviors and administer negative consequences to those who perform them. Although this approach is favored by governments, ABA practitioners typically avoid this approach in community interventions for a variety of reasons. One practical reason is that this approach usually requires extensive enforcement in order to be effective, and enforcement requires backing by the proper authority. For example, an ordinance that fined residents for throwing aluminum cans in the garbage would need some reliable way to observe this unwanted behavior, which, obviously, would not be easy.

The main reason ABA practitioners have opposed the use of behavioral penalties is the effect it has on the attitudes and long-term behaviors of the target audience. As discussed above, most individuals react to punishment with negative emotions and attitudes (Sidman, 1989). Instead of performing a behavior because of its positive impact, they simply do it to avoid negative consequences and, when enforcement is not consistent, behaviors are likely to return to their previous state.

Astute readers will note the label “penalty” rather than “punishment.” Likewise, the term “reward” is used instead of “positive reinforcement.” This distinction is needed to differentiate the technical and the application meanings of these consequence strategies. Specifically, reinforcement and punishment imply the consequence changed the target behavior. If punishment does not decrease behavior or reinforcement (positive or negative) does not increase behavior, the relevant consequences were not punishers or reinforcers. In other words, punishment and reinforcement are defined by the effects of the consequence on the target behavior. Because large-scale or community-based applications of consequence strategies rarely define the behavioral impact per individual, the terms penalty and reward are more appropriate. Regardless of behavioral impact, penalties are negative consequences and rewards are positive consequences.

Rewards

Because of the negative side effects associated with punishment, ABA practitioners favor the strategy of following a desirable behavior with a positive consequence, or reward. Rewards include money, merchandise, verbal praise, or special privileges, given as a consequence of the desired target behavior. Although reward strategies have some problems of their own, many community-based reward interventions have produced dramatic increases in targeted behaviors.

Because rewards follow behaviors, they are included in the consequence section of this research-paper. However, rewards are often preceded by behavioral antecedents announcing the availability of the reward following a designated behavior. This activator is termed an incentive. Similarly, an antecedent message announcing punitive consequences for unwanted behavior is termed a disincentive. Sometimes rewards or penalties are used without incentives or disincentives. In these cases, the positive or negative consequence follows the behavior without an advanced announcement of the response-consequence contingency.

Incentive/reward programs have targeted a wide range of behaviors. For example, studies have shown significant beneficial impact of incentive/reward programs at increasing vehicle safety-belt use (Geller et al., 1989), medication compliance (Bamberger et al., 2000), commitment to organ donation (Daniels, Hollenback, Cox, & Rene, 2000), and decreasing drug use (Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1999) and environmental degradation (Lehman & Geller, 2004).

In addition, employers frequently and effectively use incentives and rewards to increase worker productivity and safety. A meta-analysis of 39 studies using financial incentives to increase performance quantity found that, averaged across all studies, workers offered financial compensation for increased production increased their productivity by 34 percent over those workers who were not offered behavior-based rewards (Jenkins, Mitra, Gupta, & Shaw, 1998). Behavior-based incentive-reward strategies are also effective at increasing safety-related behaviors and thereby preventing personal injury (Geller, 2001; McSween, 2003).

Given the consistent effectiveness of incentive/reward strategies, one might ask, “Why use anything else?” Unfortunately, incentive/reward interventions have a few disadvantages. An obvious practical disadvantage of using rewards is they can be expensive to implement from both a financial and administrative perspective.

A second limitation is the target behaviors tend to decrease when the rewards are removed almost as dramatically as they increased when the rewards were introduced. In fact, this effect is so reliable that ABA researchers often use this effect to evaluate intervention impact. They first measure the preintervention (baseline) frequency of a target behavior, then assess the increase in the frequency of the behavior while rewards are in place, and finally document a decrease in behavioral frequency when the rewards are removed.

When ABA researchers show a target behavior occurs more often while an intervention is in place and returns to near baseline levels when the intervention is withdrawn, they demonstrate functional control of the target behavior: The intervention caused the behavior change. An obvious solution to this reversal problem is to keep a reward strategy in place indefinitely. Bottle bills, which provide a refund of 5 to 10 cents per bottle or can recycled, illustrate an effective long-term incentive/reward strategy.

Finally, reward interventions have been criticized by some researchers who contend rewards diminish intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The contention is that instead of focusing on the positive aspects of completing a task for its own sake, individuals become extrinsically motivated to perform the behavior. In essence they reason, “If someone is paying me to perform a behavior, the activity must be unpleasant and not worth performing when the opportunity for reward is removed.”

Figure 98.4 illustrates this overjustification effect (Lepper & Green, 1978). The prior extrinsic reward for solving a math problem takes the student’s attentions away from the intrinsic or natural consequences of the behavior—solving an important problem. Interpersonal recognition and feedback interventions call attention to the target behavior and can therefore enhance intrinsic motivation (Geller, 2001, 2005).

Feedback

Feedback strategies provide information to participants about their behavior. They can make the consequences of desirable behaviors more salient (e.g., money saved from carpooling, amount of weight lost from an exercise program), and increase the frequency of behaviors consistent with desired outcomes.

Figure 98.4 Extrinsic rewards can stifle intrinsic motivation. SOURCE: Illustration by George Wills.

Figure 98.4 Extrinsic rewards can stifle intrinsic motivation. SOURCE: Illustration by George Wills.

Feedback strategies were used in many early environmental-protection interventions targeting home-energy consumption, and most of these interventions showed modest but consistent energy savings (e.g., Dwyer, Leeming, Cobern, Porter, & Jackson, 1993; Geller et al., 1982). Other research has demonstrated feedback to be an effective strategy for addressing unsafe driving (Ludwig & Geller, 2000), smoking behavior (Walters, Wright, & Shegog, 2006), and depression (Geisner, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2006).

Although I reviewed these six ABA intervention techniques (education, prompts, modeling, commitment, rewards, and feedback) separately, in practice several are often combined in a single intervention process. For example, most interventions combine some sort of antecedent information component with a behavior-based consequence (e.g., reward and/or feedback). The reward or feedback can be based on participants’ behavior (i.e., process-based) or based on the cumulative results of several behaviors from one individual or a team of individuals (i.e., outcome-based).

It’s important to apply behavior-based and outcome-based consequences strategically. In other words, the behavior-consequence contingency defines an accountability system, which in turn influences the participant’s behavior. For example, outcome-based feedback and reward programs to promote industrial safety are popular worldwide because they are easy to implement and they decrease the reports of injuries. More specifically, employees receive rewards (e.g., gift certificates, lottery tickets, or financial bonuses) when the companywide injury rate is reduced to a certain level. The result: Rewards are received because the frequency of reported injuries decrease.

However, most of these outcome-based incentive/reward programs do more harm than good. Why? Because actual safety-related behaviors do not change—just the reporting of injuries. When the reporting of injuries is stifled by outcome-based incentives and rewards, critical conversations about injury prevention decrease. Figure 98.5 (next page) illustrates how rewards for outcomes can have a detrimental effect on behavior. Managers get what they reward.

Summary

This research-paper reviewed the fundamental principles and procedures of ABA and gave some research-based examples of useful ABA interventions. However, a brief introduction to ABA cannot sufficiently portray the potential of this approach to mitigate the diverse problems facing contemporary society. Thus, this research-paper only scratched the surface of the ABA domain, from analyzing the behavioral components of social issues to implementing and disseminating cost-effective strategies for large-scale behavior change.

Figure 98.5 Outcome-based consequences remove focus from process behaviors.

I presented several principles of ABA, along with the rationale and implications of each. However, many additional operational definitions and practical applications of these principles are available. For example, The Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis has been reporting evidence-based exemplars of these principles since its inception in 1968, and institutions, industries, and communities have been reaping the benefits of ABA for over four decades.

Numerous colleges and universities offer undergraduate and graduate courses in ABA, and 12 graduate programs have been accredited by the Association for Behavior Analysis International for their MS and/or PhD degrees in ABA. Five of these universities (i.e., Ohio State University, University of Kansas, University of Nevada at Reno, West Virginia University, and Western Michigan University) offer PhDs in ABA, with diverse attention to real-world applications (ABA International, 2007).

Thus, ABA specialists are increasing in numbers worldwide, thereby adding to a burgeoning repertoire of socially valid ways to improve the human dynamics of societal concerns with positive, practical, and cost-effective behavior-change intervention.

References:

- Association for Behavior Analysis International. (2007). Convention program for the 33rd Annual ABA Convention, San Diego, CA.

- Alvero, A. M., Bucklin, B. R., & Austin, J. (2001). An objective review of the effectiveness and characteristics of performance feedback in organizational settings. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 21, 3-29.

- Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359-372.

- Azrin, N. H., & Holz, W. C. (1996). Punishment. In W. K. Honig (Ed.), Operant behavior: Areas of research and application (pp. 380-447). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Bamberger, J. D., Unick, J., Klein, P., Fraser, M., Chesney, M., & Katz, M. H. (2000). Helping the urban poor stay with antiretroviral HIV drug therapy. American Journal of Public Health. 90, 699-701.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Carnegie, D. (1936). How to win friends and influence people. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and practice (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Covington, M. V. (1992). Making the grade: A self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Covington, M. V., & Omelich, C. L. (1979). Are causal attributions casual? A path analysis of the cognitive model of achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1487-1504.

- Daniels, D. E., Hollenback, J. S., Cox, R. R., & Rene, A. A. (2000). Financial reimbursement: An incentive to increase the supply of transplantable organs. Journal of the National Medical Association, 92, 450-454.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Publishers.

- Dwyer, W. O., Leeming, F. C., Cobern, M. K., Porter, B. E., & Jackson, J. M. (1993). Critical review of behavioral interventions to preserve the environment: Research since 1980. Environment and Behavior, 25, 485-505.

- Estes, W. K., & Skinner, B. F. (1941). Some quantitative properties of anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 29, 390-400.

- Geisner, I. M., Neighbors, C., & Larimer, M. E. (2006). A randomized clinical trial of a brief, mailed intervention for symptoms of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 393-399.

- Geller, E. S. (Ed). (1991). Social validity: Multiple perspectives. Monograph Number 5. Lawrence, KS: Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, Inc.

- Geller, E. S. (2001). The psychology of safety handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Geller, E. S. (2005). People-based safety: The source. Virginia Beach, VA: Coastal Training and Technologies Corporation.

- Geller, E. S., & Johnson, D. J. (2007). The anatomy of medical error: Preventing harm with people-based patient safety. Virginia Beach, VA: Coastal training and Technologies Corporation.

- Geller, E. S., Kalsher, M. J., Rudd, J. R., & Lehman, G. (1989). Promoting safety belt use on a university campus: An integration of commitment and incentive strategies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19, 3-19.

- Geller, E. S., Winett, R. A., & Everett, P. B. (1982). Environmental preservation: New strategies for behavior change. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Gilbert, T. F. (1978). Human competence—Engineering worthy performance. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Greene, B. F., Winett, R. A., Van Houten, R., Geller, E. S., & Iwata, B. A. (Eds.). (1987). Behavior analysis in the com-munity: Readings from the Journal of Applied Behavior. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

- Hagenzieker, M. P. (1991). Enforcement or incentive? Promoting safety belt use among military personnel in the Netherlands. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 23-30.

- Jenkins, G. D., Mitra, A., Gupta, N., & Shaw, J. D. (1998). Are financial incentives related to performance? A meta-analytic review of empirical research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 777-787.

- Lehman, P. K., & Geller, E. S. (2004). Behavior analysis and environmental protection: Accomplishments and potential for more. Behavior and Social Issues, 13, 13-32.

- Lepper, M., & Green, D. (Eds.). (1978). The hidden cost of reward. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Lewin, K. (1958). Group decision and social change. In E. E. Maccoby, T. M. Newcomb, & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology (pp. 197-211). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Ludwig, T. D., & Geller, E. S. (2000). Intervening to improve the safety of delivery drivers: A systematic, behavioral approach. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 19, 1-124.

- Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1976). Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 105, 3-16.

- McSween, T. E. (2003). The values-based safety process: Improving your safety culture with a behavioral approach (2nd ed.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- O’Brien, D. P. (2000) Business measurements for safety performance. New York: Lewis Publishers.

- Parsons, H. M. (1974). What happened at Hawthorne? Science, 183, 922-932.

- Rhodewalt, F. (1994). Conceptions of ability achievement goals, and individual differences in self-handicapping behavior: On the application of implicit theories. Journal of Personality: 62, 67-85.

- Sidman, M. (1989). Coercion and its fallout. Boston: Authors Cooperative, Inc., Publishers.

- Silverman, K., Chutuape, M., Bigelow, G. E., & Stitzer, M. L. (1999). Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcement magnitude. Outcomes Management, 146, 128-138.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group.

- Skinner, B. F. (1950). Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review, 57, 193-216.

- Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Walters, S. T., Wright, J., & Shegog, R. (2006). A review of computer and Internet-based interventions for smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 264-277.

- Werner, C. M., Rhodes, M. U., & Partain, K. K. (1998). Designing effective instructional signs with schema theory: Case studies of polystyrene recycling. Environment and Behavior, 30, 709-735.

- Whitehead, T. N. (1938). The industrial worker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wiegand, D. M., & Geller, E. S. (2005). Connecting positive psychology and organizational behavior management: Achievement motivation and the power of positive reinforcement. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 24, 3-25.

- Winett, R. A., Leckliter, I. N., Chinn, D. E., Stahl, B., & Love, S. Q. (1985). Effects of television modeling on residential energy conservation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18, 33-44.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.