This sample Arousal in Sport Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Arousal in sport and exercise is a human condition that ranges along a continuum from sleep to high excitation and is expressed physiologically, cognitively, and behaviorally. Three prominent theories of arousal in sport are drive theory, the inverted-U hypothesis, and reversal theory. Each has unique insights for the discussion of an athlete’s ability to perform at optimal levels on the playing field or court and can guide an astute coach, counselor, or psychologist in his or her work. Lastly, the application of cognitive, behavioral, and cognitive–behavioral interventions for arousal regulation are discussed.

Outline

- Introduction

- Conceptual Confusion Surrounding Arousal

- Neuropsychology of Arousal

- Arousal Theories

- Effects of Arousal on Athletic Performance

- Managing Arousal Levels

1. Introduction

The coach gathers the team moments before the championship game for a pep talk laden with fire, brimstone, and proclamations of victory. The professional basketball player sits on the training room table, tattoos lining his arms, bobbing his head rhythmically to the music on his headphones. The sprinter takes a few quick strides, bounds up and down a couple of times, and takes two good deep breaths before assuming her position in the starting blocks. The stock car racer says a short prayer and finds a brief moment of silence before sliding into his car and heading out to the starting line. Excellent athletic accomplishments require the athlete’s body to be appropriately energized, with physiological and psychological resources prepared for the stresses and physical demands of competition.

The preceding instances describe the concept of arousal and its regulation in sport. The term ‘‘arousal’’ has been a part of the English language for more than 400 years. The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘‘arouse’’ as ‘‘to raise up from sleep or inactivity, to excite.’’ James, in his classical work Principles of Psychology, used the term ‘‘arousal’’ to describe ‘‘activation.’’ Arousal, as it is used in sport, describes a condition of controlled or uncontrolled preparedness and manifests itself in varying levels of mental activity, emotional display, physical energy, and concomitant physiological reactivity.

2. Conceptual Confusion Surrounding Arousal

Besides the historical reference of exciting one to action, being aroused typically refers to physiological responses. That is, aroused individuals demonstrate high heart rates, increased sweat response, increased brain activity, and (typically) increased intensity of physical effort.

A perusal of the general psychology and sport psychology research over the past five decades shows that arousal is often used interchangeably with terms such as anxiety, activation, emotion, motivation, and psychic energy. This understandably has resulted in conceptual confusion. The early researchers of arousal, such as Cannon, Duffy, Hebb, and Malmo, treated arousal as a unidimensional physiological construct. Today, arousal is viewed as a multidimensional construct that includes a physiological dimension paired/ grouped with cognitive, affective, and/or behavioral dimensions. For example, an ice hockey player who is optimally aroused would have an elevated heart rate, increased beta waves, increased respiration, and increased adrenalin. In addition, thought processes would be alert and focused, such that the player is able to read and react to on-ice situations quickly and accurately. The optimally aroused athlete would also be in control of essential affective states and would demonstrate ‘‘passion’’ or intensity in play.

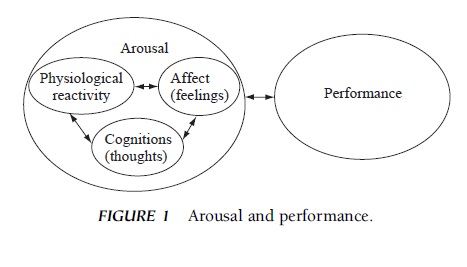

The physiological component of arousal can be represented in a number of ways such as through muscle tension, cortical activity, electrodermal activity, respiration, and biochemical markers (e.g., epinephrine, cortisol). The cognitive interpretation appraisal component can influence the physiological component. Furthermore, the affective component can also interact with thoughts to influence physiological responses and athletic performance (Fig. 1).

3. Neuropsychology Of Arousal

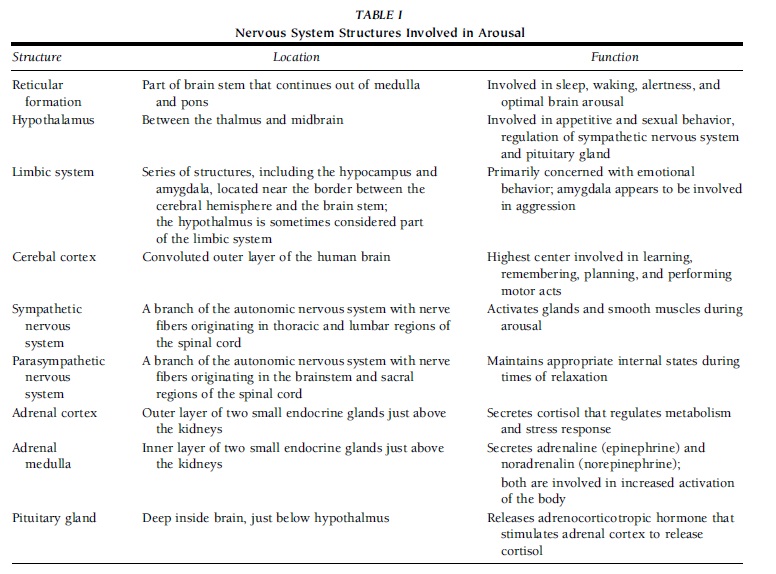

During recent years, much has been learned about the neurological and biochemical mechanisms involved in human arousal. Preparation for competition, as well as competition itself, sets off a chain of events in the central nervous system and autonomic nervous system that results in arousal. Table I provides a summary of nervous system structures involved in arousal as well as the locations and functions of the structures.

4. Arousal Theories

A number of theories have been proposed to explain the relationship between arousal and athletic performance. Following is an analysis of the major perspectives.

4.1. Drive Theory

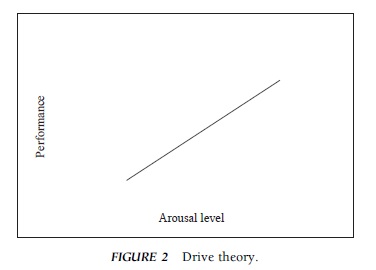

The drive theory of arousal states that arousal has a positive correlation with athletic performance, particularly in cases of skills that are well learned (Fig. 2). The theory is based on the classical work of Hull, who stated that drive (or arousal) multiplied by habit strength (amount of prior learning) determines an individual’s level of performance:

Performance = Drive x Habit Strength:

As emotions and excitement increase, so does an athlete’s performance.

FIGURE 1 Arousal and performance.

FIGURE 1 Arousal and performance.

Mediating the role of anxiety on an athlete’s performance is habit strength. Habit strength speaks to how well an individual has learned particular skills. The better learned a skill (or the more skilled the athlete), the more likely arousal is to enhance athletic performance. Some researchers have even gone so far as to been closely associated with the concept of social facilitation, some have questioned whether the arousal–performance relationship depicted exists in all motor activities required in sport. The hypothesis is well accepted for gross motor tasks requiring strength and speed, but it is less well accepted for tasks requiring balance, accuracy, and fine motor skills (e.g., putting a golf ball).

TABLE I Nervous System Structures Involved in Arousal

TABLE I Nervous System Structures Involved in Arousal

Drive theory is most beneficial to practitioners in understanding the link between skill level and optimal arousal. It is unlikely that an excellent athlete facing an easy task will garner sufficient emotional and physiological motivation to perform at his or her best. In such a situation, it benefits that athlete to set challenging process goals for the task at hand, in essence increasing the perceived challenge of the task. Conversely, regardless of the potential benefits of arousal to explosive movements and strength, a novice athlete will not reap great rewards from achieving exceptional arousal levels. Such an athlete should be counseled to find a state of calm that allows him or her to feel comfortable on the playing field or court.

FIGURE 2 Drive theory

FIGURE 2 Drive theory

4.2. Inverted-U Hypothesis

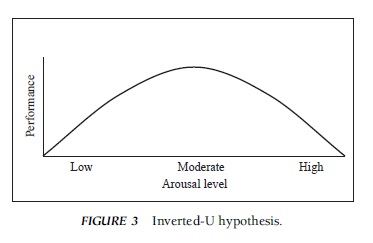

The inverted-U hypothesis states that moderate levels of arousal are ideal for optimal athletic performance (Fig. 3). Performance gradually improves as a competitor goes from underarousal to the alert state of moderate arousal, after which point performance declines as the individual becomes overaroused.

Unlike drive theory, the inverted-U hypothesis does state that there is a point of arousal that exceeds what is needed for excellence on the playing field. Yet since the original model posed in 1908 by Yerkes and Dodson, it has been suggested that one must account for task difficulty, unique sporting demands, ability level of athletes, and individual differences when employing the inverted-U hypothesis. For example, it has been suggested that the peak of a golfer’s inverted U ought to be at relatively lower levels of arousal, whereas a sprinter’s inverted U will exist at high levels of arousal. In both instances, too little arousal or too much arousal is debilitative, yet the midranges of arousal differ due to sporting demands. Therefore, it is suggested that although the arousal– performance relationship is that of an inverted U, the placement of this inverted U on the arousal continuum ought to vary due to sport demands and individual differences.

The inverted-U hypothesis is perhaps most readily embraced by those in sport psychology practice. This is due in part to the fact that its simplicity (a unidimensional model as opposed to a theory that considers arousal and anxiety or multiple forms of anxiety) makes it easily understood by athletes and coaches. An athlete’s ability to move into and out of ideal performance states is clear by drawing an upside down U on a piece of paper. This theory is also appreciated by practitioners because it recognizes the possibility of overarousal. This further illuminates the challenges posed by a ‘‘one size fits all’’ fire and brimstone pep talk.

4.3. Reversal Theory

Unlike other theories, the foundation of reversal theory is an athlete’s interpretation of arousal rather than how high or low the energizing state is. Individual differences in perception determine how facilitative or debilitative arousal levels are. Depending on the situation that the athlete faces, arousal levels might be interpreted as ‘‘anxiety’’ or ‘‘excitement.’’ For example, high levels of arousal might be interpreted by one athlete as lack of preparedness, whereas the same elevated arousal could be perceived as the appropriate energy for athletic success by another. Furthermore, at the root of this theory is the ability to change (i.e., reverse) one’s interpretation of arousal. The reversal of interpretation might lie in improved skill levels (through practice), realization that tasks are not as challenging as thought previously, or support of coaches or teammates. Ultimately, according to this model, optimal performance is achieved when a player’s preferred arousal level is in harmony with his or her actual arousal levels.

Sport psychology coaches who understand the reversal theory often see the importance of cognitive restructuring. The fact that perceptions of threats and opportunities on the playing field can change the facilitative nature of arousal makes an athlete’s beliefs and thought processes essential for success. Regardless of the situation, an athlete nearly always has an opportunity to find his or her ideal arousal level. For example, a loud and hostile crowd could be perceived as an ‘‘extra player’’ for the home team, reducing the visiting team members’ good feelings and confidence (i.e., debilitative perceptions). Conversely, the visiting team members could see and hear the hostile crowd and think, ‘‘We must be good! This crowd is worried and needs to help their team’’ (i.e., a facilitative perception). Drawing from the teachings of cognitive and/ or rational–emotive therapies can be very useful to a practitioner who appreciates the reversible nature of arousal’s effects on athletic performance.

4.4. Newer Theories

Other theories related to arousal in sport performance are the Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning (IZOF), the multidimensional anxiety theory, and the Cusp Catastrophe Model. Hanin suggested that in the IZOF, each individual has a certain level of emotion where he or she competes optimally. This ‘‘zone’’ of emotion can be high, low, or somewhere in between, depending on each person’s unique cognitive, physiological, and technical resources. The multidimensional anxiety theory suggests that cognitive anxiety (i.e., thoughts/worries) has an inverse linear relationship with performance, whereas somatic anxiety (i.e., physiological) displays an inverted-U relationship with performance. Lastly, the Cusp Catastrophe Model states that one must consider cognitive anxiety, physiological arousal, and performance demands simultaneously. In this theory, the relationship between anxiety/arousal and performance is not a neat linear one but rather one that can be filled with great peaks and valleys. In particular, one can achieve the greatest performances under high cognitive stress and arousal but, at the same time, can experience the greatest performance decline when things go awry.

FIGURE 3 Inverted-U hypothesis.

FIGURE 3 Inverted-U hypothesis.

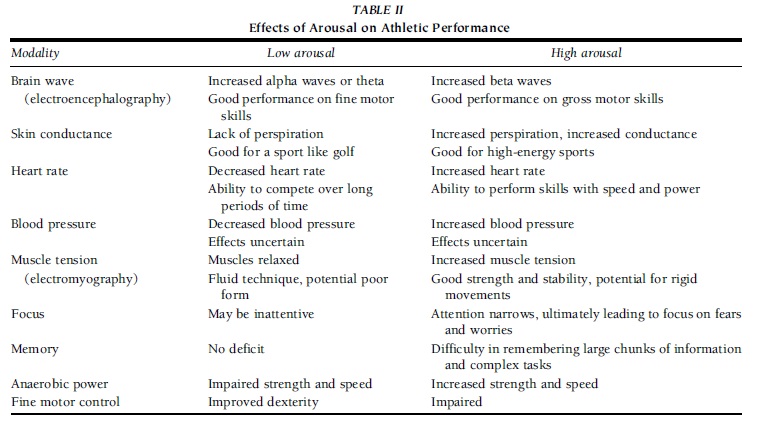

5. Effects Of Arousal On Athletic Performance

Arousal levels directly influence physiological, cognitive, and motor modalities necessary for excellence on the playing field (Table II). Understanding these modalities can help in the identification and management of underarousal and over arousal. Physiologically, modalities measurable through psychophysiological monitoring, such as brain waves, skin conductance, heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension, all are elevated when an individual is aroused. Although these modalities are directly related to somatic arousal, each must be carefully measured because most are automatically increased during physical exertion. Perhaps the speed of recovery to ‘‘normal’’ levels between points and after play is when the goodness of one’s arousal level is most apparent. Arousal level also influences one’s cognitive functioning. It is suggested that an athlete beyond his or her optimal arousal level is likely to suffer from poor decision making, impaired memory, and rushed thinking. Nideffer posited that in sport, heightened arousal levels also impair an athlete’s ability to focus on the task at hand. Contrary to the lay assumption that over aroused athletes think too much, it is suggested that being outside one’s optimal arousal zone leads to thinking about the wrong things at the wrong time. In particular, Nideffer suggested that one begins to concentrate on thoughts, emotions, and feelings (specifically fear and worry). There is little to suggest that underarousal significantly influences one’s cognitive abilities, yet at low arousal levels few athletes are able to garner the necessary energy and alertness to succeed at the physical tasks of sport.

TABLE II Effects of Arousal on Athletic Performance

TABLE II Effects of Arousal on Athletic Performance

6. Managing Arousal Levels

There are many psychological techniques that allow one to effectively manage arousal levels. Understanding that arousal, anxiety, concentration, confidence, and physiological modalities all are inherently linked, it is clear that there are many approaches to help athletes find and maintain facilitative levels of arousal. Interventions can be broken down into three categories: cognitive, behavioral, and cognitive–behavioral. (Although dividing interventions into these categories is useful in understanding the practice of sport psychology, it is important to recognize that the mind and body are inherently linked. This reminds one that these categories are not mutually exclusive.)

6.1. Cognitive Interventions

Increasing an athlete’s awareness about his or her optimal arousal levels is the foundation of an intervention. Developing awareness might be achieved through successive post performance reflections that examine levels of excitement, concentration, emotions, and confidence during a competition. Similarly, a retrospective comparison of ‘‘best performances’’ versus ‘‘worst performances’’ can paint a powerful picture of an athlete’s optimal arousal state.

Setting realistic and motivating goals gives an athlete the ability to energize while maintaining appropriate focus. It is appropriate to have a ‘‘mission’’ or goal for one’s career and season as well as for each practice and competition. Goals direct an athlete (i.e., energizing) and clarify purpose (i.e., minimizing stress and relaxing). Cognitive restructuring and self-talk can appropriately energize an athlete and calm him or her down when necessary. Cognitive restructuring fits nicely with the reversal theory of arousal, suggesting that modifying one’s perspective and thoughts will help the athlete to find appropriate activation levels. Self-talk or the use of cue words can energize (i.e., ‘‘quick feet’’) or calm down (i.e., ‘‘slow and smooth’’) an athlete when necessary. Thought stoppage allows an athlete to catch himself or herself when he or she begins to focus on task-irrelevant cues.

Mental imagery, another cognitive intervention, is popular in the field of sport psychology. A good imagery session in which the body is relaxed and all of the senses are incorporated can be used to relax or energize an individual. Accessing one’s memory bank of sporting highlights can serve as very motivational imagery, hence increasing arousal levels. Conversely, imagery can be used to escape from the stresses of competition, consequently reducing arousal.

6.2. Behavioral Interventions

There are a variety of relaxation techniques that can benefit an athlete who is over aroused. The following are a few techniques that are used regularly by sport psychology practitioners: controlled breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, relaxation response, and biofeedback. A few of these interventions can also be used by an athlete to energize, specifically quick shallow breathing and gaining understanding of excited physiological levels through biofeedback. Actions such as quick sprints, jumping rope, and dynamic stretching also serve to energize the underaroused athlete.

6.3. Cognitive–Behavioral Interventions

Both cognitive and behavioral techniques are combined during preperformance preparation and competitive routines. Prior to a competition, successful athletes commonly engage in activities such as setting goals, listening to music, using mental imagery, and physically warming up so as to have optimal arousal at the start of the competition. Similarly, while in the midst of play, athletes often use competitive routines to relax and refocus. Using a physical cue to put a prior play in the past, engaging in mental planning, and taking a good breath or two to help focus attention are often elements of such a routine. Routines are commonly used in sports where the flow of play is intermittent such as tennis, baseball, and golf.

Bibliography:

- Dienstbier, A. (1989). Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychological Review, 96, 84–100.

- Hanin, Y. (2000). Emotions in sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Kerr, J. H. (1985). The experience of arousal: A new basis for studying arousal effects in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 3, 169–179.

- Nideffer, R. M. (1989). Attention control training for sport. Los Gatos, CA: Enhanced Performance Services.

- Spence, J. T., & Spence, K. W. (1956). The motivational components of manifest anxiety: Drive and drive stimuli. In D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety and behavior (pp. 291–326). New York: Academic Press.

- Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology of Psychology, 18, 459–482.

- Zaichkowsky, L., & Baltzell, A. (2001). Arousal and performance. In R. N. Singer, H. A. Hausenblas, & C. M. Janelle (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (pp. 319–339). New York: John Wiley.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.