This sample Assessment in Sport Psychology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Assessment enables sport psychology professionals (SPPs) to obtain crucial performance-relevant information. The principal aim is to help athletes perform at an optimal level. To this end, both formal and informal methods are employed. These include interviews, behavioral observation, psychological testing, surveys, and inventories. Effective assessment requires sensitivity to test validity and reliability, response sets and styles, consensual validation, and ethical requirements. This research paper includes a brief history and a discussion of future directions.

Outline

- Introduction

- Role of Assessment

- Methods of Assessment

- Common Distinctions

- History and Current Assessment Tools (North American)

- List and Description of Frequently Used Tests

- Formal Assessment Guidelines and Ethical Considerations

- Future Directions

1. Introduction

At its most basic level, assessment involves information gathering, interpretation, and evaluation. We all constantly engage in one form of assessment or another. It is how we make sense of the world. Sport psychology assessment is the systematic attempt to measure psychological characteristics with the aim of improving sport experience and performance. Within the field of applied sport psychology, the method of assessment typically depends on the context (e.g., purpose, clients, time constraints). Although most sport psychology professionals (SPPs) associate assessment with more formal approaches (typically paper-and-pencil questionnaires and now online questionnaires), there are a variety of ways in which information can be collected and distilled. This research paper focuses on the practical applications of assessment and its use in applied settings. It also provides general information on selected assessment methods and a number of widely used instruments and tests.

2. Role Of Assessment

SPPs use assessment to gain crucial information about the people with whom they work. The aim is to help each of these individuals reach the level of performance desired, whether this is the level of a professional or Olympic athlete, an amateur competing in organized club competition, or a purely recreational sport enthusiast. But what exactly does an SPP need to understand about an individual to help? The answer to this question is controversial. Some SPPs believe that a clinical understanding of the client is necessary. Most SPPs focus on gaining more direct performance-relevant information (e.g., how the athlete pays attention, under what situations performance breaks down). Even if there were agreement on exactly what should be assessed, it would be difficult to get agreement on assessment methods. This difficulty increases where there is no agreement on which factors are most important.

There are four primary applications of applied sport assessment:

- Performance enhancement (individual and team)

- Athlete selection and screening

- Injury recovery

- Sport enjoyment

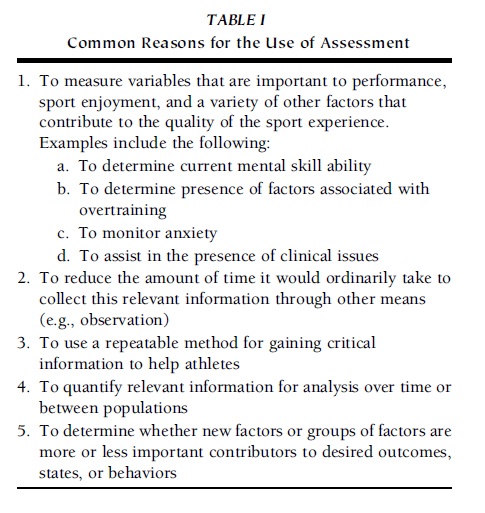

Some SPPs believe that all applications can be subsumed under the primary category of performance enhancement. Others emphasize the importance of having a positive sporting experience regardless of performance issues. Most people choose to work with SPPs because they want to be better at their sport. The presenting issue may be ‘‘recovering quickly from an injury,’’ ‘‘resolving conflicts among team members,’’ or ‘‘identifying mental strengths and liabilities,’’ but the bottom-line concern is with performance (Table I).

TABLE I Common Reasons for the Use of Assessment

TABLE I Common Reasons for the Use of Assessment

3. Methods Of Assessment

SPPs apply a variety of assessment methods to understand, predict, and modify behavior, including the following:

- Interviews

- Behavioral observation (including video review)

- Psychological testing, surveys, and inventories

- Third-party anecdotal data collection (from parents, coaches, teammates, etc.)

Typically, context will help to determine the most appropriate methods to employ. In most situations, SPPs will gather information using more than one of these methods.

3.1. Interviews

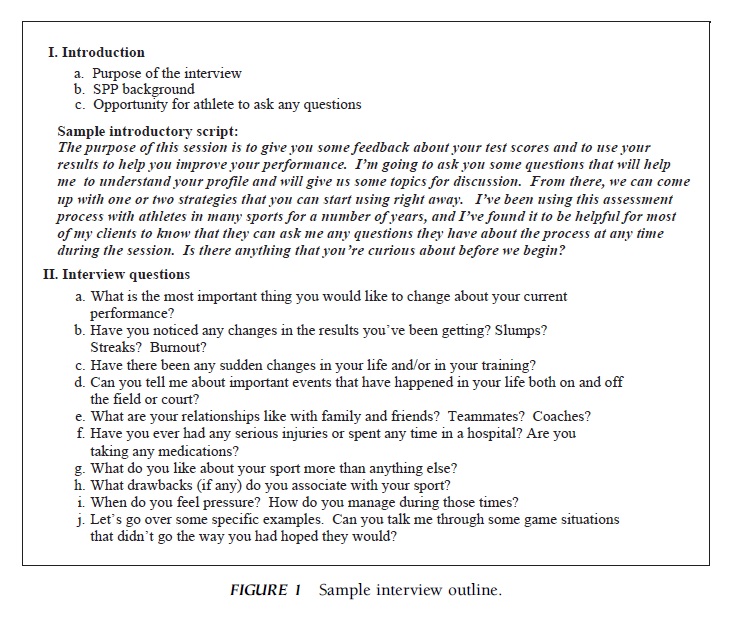

The most common form of assessment takes place through the process of formal and informal interviewing. There are typically three purposes for conducting an interview: to identify performance issues, to determine ways in which to intervene, and to validate inventory and questionnaire data. The interview itself can be structured by a set of preestablished questions and topics, or it can be free-flowing with a more open and dynamic feel. Topics and lines of inquiry depend on many factors, including the type of SPP–athlete relationship, the phase of the intervention/program, the severity of the issue(s), and the objective of the work. Many items on sport psychology inventories had their origins as interview questions. This should not be surprising. Like physicians who use intake forms and a wide range of tests to help learn about their patients, so too are SPPs interested in providing an efficient and consistent way in which to get to know their clients (Fig. 1).

3.2. Behavioral Observation

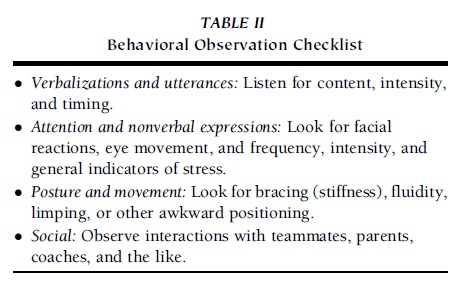

Behavioral observation is a straightforward process that involves watching live or recorded performance. It provides at least one distinct advantage over all of the other assessment methods in that SPPs can see firsthand how athletes behave in the most relevant settings (e.g., practice, competition). This information is invaluable because there are cues that may be identified in real-life settings that might not arise under less realistic conditions. Athletes might consistently make mistakes in situations but be unaware of the cause. The purpose of behavior observation is to watch athletes perform in those situations where insight into psychological performance factors can be ascertained. Both structured (i.e., controlled) and unstructured observation can be used to acquire this type of information. Trained SPPs can learn a great deal by attending to a variety of ‘‘targets’’ that include, but are not limited to, actual performance, verbal behavior, and body language. For example, slumped shoulders after a missed shot might reflect a slip in confidence. These kinds of observations can provide invaluable discussion points that can be critical in helping athletes to understand themselves and their performances (Table II).

TABLE II Behavioral Observation Checklist

TABLE II Behavioral Observation Checklist

3.3. Psychological Testing, Surveys, and Inventories

Although the definition of assessment offered here is rather broad, most people identify assessment with the printed questionnaire. Ranging from several questions to several hundred questions, these instruments usually ask athletes to respond to items by selecting from some form of multiple-choice response list. It should be noted that many SPPs are careful not to use the label ‘‘test’’ and prefer instead to use a variety of more ‘‘acceptable’’ names (e.g., survey, inventory, assessment). There are many ways in which instruments may be categorized, with some being more theoretically sophisticated than others. The following labels are commonly applied:

- Clinical

- Cognitive

- Attentional

- Personality and emotional intelligence

- Sport-specific

- Team/Social interactive

Although these different kinds of information are not uniquely attainable through psychological testing, the advantage of such testing is that it provides a more objective, more scientific means of acquiring data. Presumably, SPPs want to be able to know as much as possible so as to improve performance. Testing can provide a scientific psychological portrait of the athletes with whom they work. Clinical inventories can inform SPPs about qualities such as depression, anxiety, bipolarity, and mania. Cognitive inventories measure things such as verbal intelligence and speed of learning. Attentional inventories identify preferred styles of concentration. Personality tests involve measures of confidence, self-esteem, social attitudes, and risk taking. Sport-specific tools provide information about performance-relevant variables in sport settings. Team and social interactive inventories can help to identify factors particularly relevant in group settings. Examples would include measures of cohesion and communication style.

3.4. Third-Party Anecdotal Data Collection

Important information that is helpful to SPPs is often acquired through formal and informal communication with people in a special position to provide insight about clients. Third-party data collection may be as simple as an interview conducted by someone other than the SPP (and, as such, may be viewed as a type of interview), but it can also be much less formally acquired information by parents, teammates, coaches, or other individuals who come in contact with the athlete. One formal version of this often-overlooked method of assessment is similar to the 360-degree review process widely used in business consulting, where an individual receives feedback on performance strengths and weaknesses from his or her superiors, peers, and subordinates so as to help formulate an individual action plan for career development. Informal versions include casual conversations and other means of information exchange.

4. Common Distinctions

4.1. Formal Assessment Versus Informal Assessment

Behavior can be studied formally or informally. An informal assessment is one that does not incorporate psychometrics or data collected for statistical analysis. Examples of informal assessment include reading nonverbal cues when speaking with someone, watching sport competitions, observing practice sessions without recording data, and interviewing athletes, coaches, and parents. Formal assessment involves data collection through psychometric tools, surveys, frequency distributions, and the like. Discussion of assessment in sport psychology is dominated by formal topics because it is relatively easy to examine the rationale, experimental design, reliability, validity, and motivation for construction of formal instruments. Informal assessment is, on the other hand, undervalued and less stable due to the difficulty in standardizing techniques. But veterans in the field develop a balance of formal assessment (which provides a scientific base for their work) and informal assessment (which allows them to anticipate client needs and come up with practical solutions to identified problems as they happen in real time). It should be noted that although this distinction is commonly accepted, it is not always so clear. For instance, controlled observations (not usually viewed as formal assessment) can incorporate observation schedules with preestablished behavior categories and, thus, provide data eligible for statistical analysis.

There is both an art and a science to assessment. It is certainly worth noting that there are a fair number of ‘‘gurus’’ in the field who work primarily by intuition and feel. Many respected SPPs rely most heavily on this ‘‘sixth sense,’’ and it is likely that assessment by gut feelings will continue into the future.

4.2. Subjective Assessment Versus Objective Assessment

The distinction between subjective assessment and objective assessment is one commonly encountered in discussions of sport psychology. In general, subjective assessment encompasses various forms of interviews and observations on the part of SPPs. Objective assessment typically refers to psychological tools such as inventories and tests. Here, the distinction seems to hinge on the role of SPPs in the assessment process. In subjective assessment, SPPs are called on to interpret behavior directly. In objective assessment, SPPs use an appropriate instrument to provide additional information or clarification relevant to assisting athletes. What tends to confuse this distinction is that there are subjective components within objective assessment as well as objective components within subjective assessment. For example, formal scripted interviewing includes a measure of objectivity, and the interpretation of psychological inventories contains a large subjective component.

4.3. State Versus Trait

Because SPPs are ultimately interested in modifying behavior to improve performance, it is critical to understand whether a particular individual characteristic is likely to change over time. Traits are enduring characteristics that are likely present in a variety of situations. States are temporary conditions that are determined by situational factors. For example, even the most confident people can experience anxiety before an important speech or a big game. This could be called ‘‘state anxiety’’ and would be dependent on the situation in which an individual found himself or herself. However, an anxious person (i.e., one with ‘‘trait anxiety’’) would likely become anxious before every speech or game. Gauging where certain characteristics fall on the state–trait continuum is helpful to SPPs as they use assessment information and apply methods of intervention.

4.4. Sport-Specific Measures Versus General Measures

Some assessment tools contain items that are framed in a sport-specific context to elicit responses more relevant to the actual performance environment of the individual test-taker. Believing that sport-specific measures provide uniquely valuable information, many test developers have created sport-specific versions of existing inventories. This raises an interesting question: Is it more or less useful for items to focus on behavior within the situational context of primary concern? Not surprisingly, there is disagreement on the answer. Some believe that important information can be missed with sport specific measures and that generally framed items will be more likely to pick up on those factors that are important in a variety of situations, including sport. This camp also believes that sport-specific items are more transparent and, thus, more easily faked or manipulated. Those who embrace sport-specific measures believe that the closer the context matches the particular performance environment of the athlete, the more validity the test will have and ultimately the more useful the results will be.

5. History And Current Assessment Tools (North American)

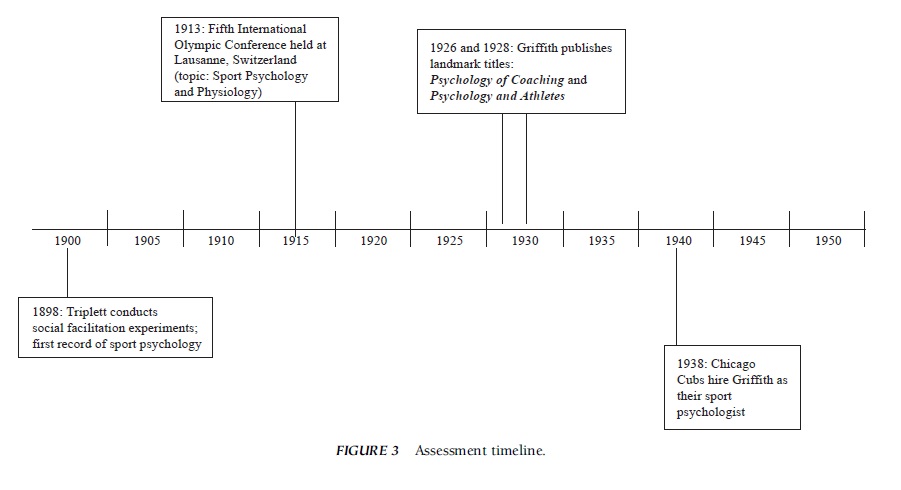

Assessment has played an integral role in the history of sport psychology. Most historical reviews identify the Triplett social facilitation experiments in 1898 as the first recorded studies in the field. In showing that cyclists raced faster with a pacer than they did by themselves, Norman Triplett used a simple measurement tool still believed by many to be the most critical component in athletic competition—results.

Nearly 30 years passed before a definitive text on the subject of athletes and their thought processes would appear. In 1926, Griffith published the first of two books that would become the ‘‘big bang’’ in the creation of sport psychology. Psychology of Coaching and Psychology and Athletics were written by Griffith as collections of his findings from the first ever sport psychology laboratory on the campus of the University of Illinois. In Psychology of Coaching, Griffith attempted to identify character types of coaches and men. His typologies included the ‘‘crabber,’’ the ‘‘silent type,’’ the ‘‘talker,’’ the ‘‘loafer,’’ the ‘‘leader,’’ and the ‘‘follower.’’

Nearly 30 years passed before a definitive text on the subject of athletes and their thought processes would appear. In 1926, Griffith published the first of two books that would become the ‘‘big bang’’ in the creation of sport psychology. Psychology of Coaching and Psychology and Athletics were written by Griffith as collections of his findings from the first ever sport psychology laboratory on the campus of the University of Illinois. In Psychology of Coaching, Griffith attempted to identify character types of coaches and men. His typologies included the ‘‘crabber,’’ the ‘‘silent type,’’ the ‘‘talker,’’ the ‘‘loafer,’’ the ‘‘leader,’’ and the ‘‘follower.’’

The 1960s were a watershed for assessment and sport psychology. The first modern inventory created specifically for use with athletes was created in 1969 by Tutko, Ogilvie, and their colleagues. The Athletic Motivation Inventory (AMI) was born out of Tutko and Ogilvie’s Problem Athletes and How to Handle Them. Until this time, application of assessment in sport settings had meant adapting results of general personality and mental health diagnostics such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF), and Thematic Apperception Tests. AMI attempted to measure traits categorized under the rubric of ‘‘Desire’’ factors and ‘‘Emotional’’ factors. Desire factors were drive, determination, aggression, leadership, and organization. Emotional factors were coachability, emotionality, self-confidence, mental toughness, responsibility, trust, and conscience development.

When international organizations began forming, communication increased between SPPs and assessment became a central focus. Could anxiety, personality, attention, moods, and motivation be tangibly measured, and could results be reliably reproduced, over time? If so, how would these tools contribute to the evolution of professional and amateur sport cultures in the real world? SPPs set to work on developing an arsenal of assessment tools for the sport environment.

One significant contributor, Rainer Martens, was a wrestling coach at the University of Montana who began to explore sport psychology after failing to help his talented team captain overcome prematch anxiety. In 1977, he published the Sport Competition Anxiety Test (SCAT) and, with help from colleagues in 1980, the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory (CSAI). Martens’ work was preceded by Spielberger’s theory that anxiety was present in both state and trait forms. Spielberger’s State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was published in 1970.

Meanwhile, Robert Nideffer’s strong interest in aikido, as well as his expertise in MMPI research, led him to conclude that attention was the key psychological factor in sport performance. He developed The Attentional and Interpersonal Style (TAIS) Inventory while at the University of Rochester in 1976. His assessment tool directly measured the attentional preferences of athletes and helped practitioners to understand the conditions in which their clients would make concentration mistakes. In a survey taken 22 years later, only one other inventory, the Profile of Mood States (POMS), was being used more than TAIS by applied SPPs. POMS is a general inventory initially created in 1971 for use in psychiatry populations. Its popularity stems from its ability to assess both current moods and dominant mood traits.

The current state of assessment in sport psychology is one of many options. A directory of sport psychology assessments published by Ostrow in 1996 included 314 different inventories, questionnaires, and surveys. Sport psychology clients now include more than just elite athletes; they include a population of serious recreational athletes and aspiring juniors in many sports. Assessment tools such as Jesse Llobet’s Winning Profile Athlete Inventory (WPAI) have been created to support developing athletes as well as professionals. Many assessments are now available on the Internet, where they can be used by athletes and practitioners from anywhere in the world in the privacy of their own homes. In professional ranks, player development and scouting departments count on psychological assessments and sport psychology consultants to help them in their coaching and drafting efforts. Examples of this application of psychological assessment include the use of AMI by the Major League Baseball Scouting Bureau and the use of Wonderlic by the National Football League (NFL) to assess intelligence levels of draft-eligible college players at the annual scouting combine. In addition, many professional teams rely on information from experts with self-designed assessments such as Robert Troutwine’s Troutwine Athlete Profile (TAP).

Biddle’s European Perspectives on Exercise and Sport Psychology provides a greater international perspective on history and current assessment tools.

6. List And Description Of Frequently Used Tests

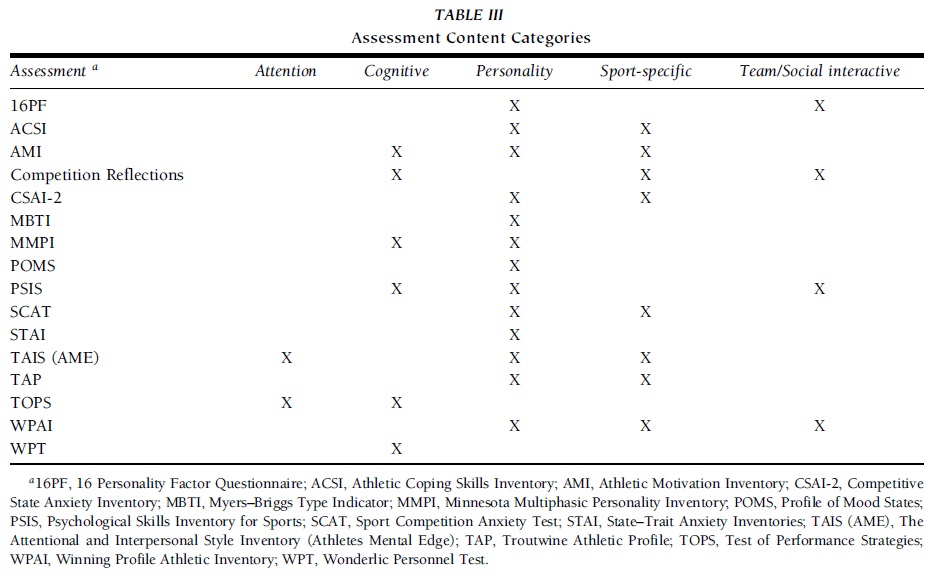

This section contains descriptions of frequently used assessments employed in the field of sport psychology. The instruments are presented alphabetically by instrument name. Table III identifies the kinds of factors or variables measured by each assessment.

6.1. 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF)

Year created: 1950

Author: Cattell

Cattell believed that human personality consisted of 46 surface traits, from which 16 primary traits can be derived. Used primarily for sport psychological research, several studies showed meaningful differences on several scales for athletes and a significant correlation between extraversion and sport success. The 16 dimensions are Warmth (cool vs warm), Intelligence (concrete thinking vs abstract thinking), Emotional Stability (easily upset vs calm), Dominance (not assertive vs dominant), Impulsiveness (sober vs enthusiastic), Conformity (expedient vs conscientious), Boldness (shy vs venturesome), Sensitivity (tough-minded vs sensitive), Suspiciousness (trusting vs suspicious), Imagination (practical vs imaginative), Shrewdness (forthright vs shrewd), Insecurity (self-assured vs self-doubting), Radicalism (conservative vs experimenting), Self-Sufficiency (group-oriented vs self-sufficient), Self-Discipline (undisciplined vs self-disciplined), and Tension (relaxed vs tense).

TABLE III Assessment Content Categories

TABLE III Assessment Content Categories

6.2. Athletic Coping Skills Inventory (ACSI-28)

Year created: 1995

Authors: Smith, Schutz, Smoll, & Ptacek

This is a 28-item inventory designed with the intent to understand how athletes deal with competitive stress. ACSI-28 measures seven sport-specific subscales and then provides an overall ‘‘power’’ ranking that is a composite of those scale scores. The power ranking is called the Personal Coping Resources score, and the subscales are Coping with Adversity, Peaking under Pressure, Goal Setting/Mental Preparation, Concentration, Freedom from Worry, Confidence and Achievement Motivation, and Coachability.

6.3. Athletic Motivation Inventory (AMI)

Year created: 1969

Authors: Tutko, Lyon, & Ogilvie

This is a 190-item, forced-choice inventory that is historically the most widely referenced in the field of sport psychology. It was developed specifically to measure traits related to elite athletic success. Traits measured are grouped as Desire factors or Emotional factors. Desire factors are drive, determination, aggression, leadership, and organization. Emotional factors are coachability, emotionality, self-confidence, mental toughness, responsibility, trust, and conscience development.

6.4. Competition Reflections

Year created: 1986

Author: Orlick

This is composed of 12 open-ended items that provide opportunities for athletes to reflect on their ‘‘best’’ and ‘‘worst’’ selves by recalling details about great and poor performances. Included within these items are four 10-point rating scales that provide some reference for perceived arousal and anxiety. Direction of the reflections leads to the athlete brainstorming changes in training, preparing for competition, and interacting with coaches.

6.5. Competitive State Anxiety Inventory (CSAI-2)

Year created: 1990

Authors: Martens, Burton, Vealey, Bump, & Smith Originally born out of Martens’ work with SCAT, this is a modification of Spielberger’s State Anxiety Inventory (SAI). The original version, created in 1980, isolated 10 items from SAI that measured competitive anxiety. A multidimensional version of the original, CSAI-2, includes three 9-item subscales measuring cognitive state anxiety, somatic state anxiety, and state self-confidence. In applied settings, a ‘‘Mental Readiness’’ form has derived from CSAI-2 that allows athletes to put themselves through a more convenient assessment of their anxiety levels while on the field or court.

6.6. Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

Year created: 1962

Authors: Myers & Briggs

Based on Jungian personality theory, this is the most widely used personality inventory in the world, with more than 2 million test takers annually. MBTI has a variety of applications in the worlds of personal development and management consulting. Its primary use in sport settings is for team cohesion and increasing awareness between teammates and coaches. Personality preference is measured along four dichotomies: Extraversion/ Introversion, Sensing/Intuition, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving. Combinations of these scales produce a four-letter acronym that reflects the dominant score on each factor. These acronyms correspond to 16 different personality types that describe persons in detail according to behaviors associated with their personalities.

6.7. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2)

Year created: 1942

Authors: Hathaway & McKinley

This is one of the cornerstones of psychiatric and clinical psychology assessment. MMPI is used to identify personality and psychosocial disorders as well as for general cognitive evaluation in adults and adolescents. A number of versions of MMPI exist, including the most recent version, MMPI-2, MMPI-A (an adolescent version), and short and long forms. Although MMPI is widely used in clinical settings, its use is limited in current applied sport psychology settings.

6.8. Profile of Mood States (POMS)

Year created: 1971

Authors: McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman

This is a 65-item instrument assessing tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion. A 5-point scale (from ‘‘extremely’’ to ‘‘not at all’’) is used to rate responses. This inventory can be used to measure both state and traitlike factors, depending on the ‘‘set’’ provided to the test taker by the proctor.

6.9. Psychological Skills Inventory for Sports (PSIS)

Year created: 1987

Authors: Mahoney, Gabriel, & Perkins

Consisting of 45 items with 5-point Likert response options, this instrument measures Anxiety Control, Concentration, Confidence, Mental Preparation, Motivation, and Team Emphasis. PSIS was created with input from 16 leading sport psychologists who answered the inventory questions as they thought the ‘‘ideal’’ athlete would. The original inventory asked true/false questions and contained 51 items. Test construction involved 713 athletes from 23 different sports.

6.10. Sport Competition Anxiety Test (SCAT)

Year created: 1977

Author: Martens

This is a 15-item inventory that was created to measure ‘‘state’’ anxiety levels in people anticipating competition. Martens was very clear in the original publication of the assessment that SCAT was not to be used to predict performance outcomes even if there was a relation to anxiety levels. Therefore, functional use of SCAT is optimal when gauging manifestations of anxiety in athletes during pregame or prematch periods.

6.11. State–Trait Anxiety Inventories (STAI)

Year created: 1970

Authors: Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene

This was originally developed as a research tool for measuring anxiety in adults and has contributed mightily to sport anxiety research in a variety of populations. STAI is composed of two 20-item scales: one measuring State Anxiety and one measuring Trait Anxiety. The context for the A-State section is how the test taker is feeling at the current time, whereas the A-Trait section is based on general feelings of anxiety. Application of STAI has led to many significant findings in athlete work. For example, Yuri Hanin used STAI to create his Zones of Optimal Functioning (ZOF) model.

6.12. The Attentional and Interpersonal Style (TAIS) Inventory

Year created: 1976

Author: Nideffer

This is a 144-item inventory with an emphasis on concentration and the critical interpersonal factors affecting performance under pressure. The latest version of TAIS is composed of 20 scales that range principally over attentional and interpersonal factors. The two newest scales are Focus over Time and Performance under Pressure. Athletes Mental Edge (AME) used a 50-item version of TAIS and was introduced in 1999. AME was the first widely used, Internet-based sport psychological assessment tool.

6.13. Troutwine Athletic Profile (TAP)

Year created: 1988

Author: Troutwine

This is a 75-item questionnaire that receives considerable attention prior to the NFL draft. Troutwine does not publish his assessment for distribution, so there are few SPPs using TAP. However, this may be the most well-known, ‘‘self-written for self-use’’ assessment in the field. The questionnaire generates a Player Report for development and a Coach Report for recruiting and selection; this is why many NFL teams privately contract with Troutwine and value his data. The Player Report measures Competitive Nature, Coping Style, Work Style, and Mental Characteristics. The Coach Report topics are Mental Makeup, Social Style, Personal Characteristics, Coaching Suggestions, and Performance Tendencies.

6.14. Test of Performance Strategies (TOPS)

Year created: 1999

Authors: Thomas, Murphy, & Hardy

This is a 64-item inventory intended for use when measuring psychological skills and strategies used by athletes both in competition and while at practice. TOPS results differentiate between practice and competitive skills and strategies on the following scales: Goal Setting, Use of Imagery, Ability to Relax, Ability to Activate/Energize, Use of Positive Self-Talk, Emotional Control, Attentional Control, Automaticity (i.e., performing without thinking), and Negative Thinking. Although TOPS is a fairly new inventory, its applied use was already seen with U.S. and Australian Olympic teams and coaches in preparation for the Sydney Games in 2000.

6.15. Winning Profile Athlete Inventory (WPAI)

Year created: 1999

Author: Llobet

This is composed of 55 items with 5-point Likert response options that measure a wide variety of psychological skills in athletes. WPAI responses load onto 10 factors: Competitiveness, Dependability, Commitment, Positive Attitude, Self-Confidence, Planning, Aggressiveness, Team Orientation, Willingness to Sacrifice Injury, and Trust. Functional use is intended for athletes from high school to professional levels for recruiting and development purposes.

6.16. Wonderlic Personnel Test (WPT)

Year created: 1937

Author: Wonderlic

This is a 50-item test of general intelligence that the user has 12 minutes to complete. Originally designed for use with job applicants in both blue and white-collar settings, WPT has become a mainstay in the assessment of collegiate football players at the NFL’s scouting combine. The test has 16 different versions with problems that include algebra, word analogies, mathematical word problems, and various other tests of verbal, computational, and analytic abilities. It measures an individual’s ability to learn, adapt, solve problems, and understand instructions.

7. Formal Assessment Guidelines And Ethical Considerations

When done well, psychological testing provides professionals with an efficient, objective, and repeatable approach to assessing behavior. Many factors affect the quality of the information gathered through the various assessment means. Sensitivity to issues around test validity, confidentiality, response sets, and response styles is critical for effective use of sport psychology assessment.

7.1. Test Validity

It is incumbent on SPPs to evaluate the validity of the assessment methods they use. A test’s validity determines how accurately it measures what it purports to measure. There are three commonly referenced types of validity: face, construct, and predictive. Face validity is a surface measure that acts as a first step toward the integrity of an assessment. Face validity is attained when the parameters of a test seem like they would generate the results that SPPs hope to generate. Construct validity links theory with practice. It can be summed up as the ability that an assessment has to demonstrate, with results, the topic it is intended to measure. Predictive validity is simply the likelihood that the results of an assessment can predict the occurrence of a specified behavior in the future.

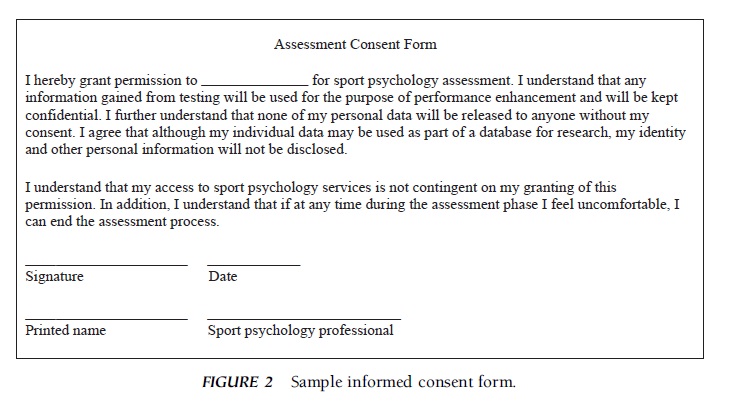

7.2. Confidentiality

According to the code of ethics set forth by the American Psychological Association, the confidentiality of the psychologist–client relationship is protected. Because many nonlicensed individuals function as sport psychology consultants, the status of such a relationship is less clear and not likely afforded the same kind of protection. When it comes to the confidentiality of assessment results, SPPs should be careful to protect confidentiality explicitly and to explain clearly to clients who will have access to their assessment information. Because it can sometimes be difficult to identify exactly who the client is (e.g., the athlete, the coach, the organization), it is advisable to have a written policy that describes how assessment information will be kept and shared. Many SPPs use informed consent forms to establish clearly the confidentiality of assessment data (Fig. 2).

7.3. Response Sets and Styles

When asking athletes to answer any set of questions about themselves, it is important to take into account variables that will influence the accuracy of their responses. Response sets are situation-specific attitudes that individuals adopt when completing a psychological assessment. They are often employed when athletes are skeptical of how their assessment data may be used. Faking can occur in situations where athletes feel pressure to present themselves in an ideal light.

In contrast to response sets, response styles reflect cross-situational, core personality characteristics. Common response styles include overly conservative and extreme appraisals. People who adopt a conservative response style see the world in shades of gray and tend to respond with middle-range answers such as ‘‘maybe’’ and ‘‘sometimes’’ on inventories with Likert scale choices. Extreme response styles are often seen in individuals who have either an overly optimistic outlook or an overly critical outlook. Aside from the impact that response sets and styles have on individual scores, SPPs must be careful when comparing different athletes’ assessment results. Although some degree of influence from both response sets and response styles is always likely to be present, their effects can be minimized by encouraging open and honest answering and by providing points of comparison for various response choices. Many SPPs prefer not to control for response sets because the sets and styles themselves provide a great deal of information about the athletes.

FIGURE 2 Sample informed consent form.

FIGURE 2 Sample informed consent form.

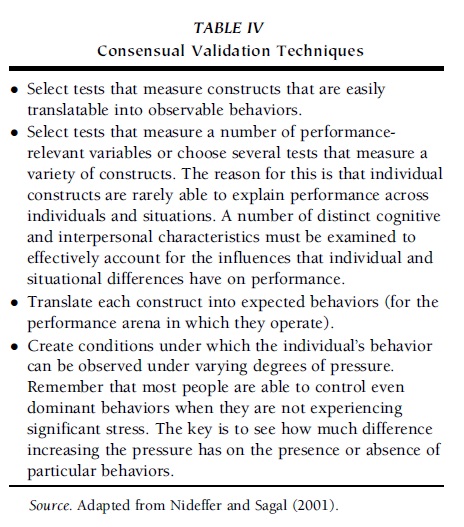

7.4. Consensual Validation

To ensure that test information is accurate, it is important to have the opportunity to speak directly with the individuals who have completed the assessments to determine the impact of any existing response sets or response styles.

Consensual validation is the process of verifying the interpretations made from test information, which typically occurs through interview or direct observation. Effective consensual validation requires the ability to define operationally psychological constructs (e.g., confidence, control). By translating these concepts into specific behaviors, SPPs can determine their presence or absence more accurately. Imagine that a client completes a personality inventory and scores very high on control and self-esteem. A high score on these dimensions would lead the interpreting SPP to assume certain behaviors in various circumstances. More often than not, the SPP would expect the client to speak up, take charge, be reluctant to listen to contrary opinions, and oppose authority. The SPP would be looking to verify that these behaviors occur with the kind of frequency commensurate with the scores on the performance relevant construct(s). Table IV offers a number of suggestions to increase effective consensual validation.

8. Future Directions

Just as athletes engage in the ‘‘pursuit of perfection,’’ SPPs seek the most effective means of helping the athletes with whom they work. Technology is already having a pronounced effect on how assessment is carried out. Psychological testing can now take place over the Internet with the tester and the testee thousands of miles apart. More and more individuals will gain access to assessment information. Feedback reports delivered instantaneously, and sometimes without professional interpretation, will most certainly force the field of sport psychology to confront what is and is not acceptable practice.

TABLE IV Consensual Validation Techniques

TABLE IV Consensual Validation Techniques

As athletes are exposed to the benefits of working with SPPs, it is inevitable that more athletes themselves will develop a professional interest in the field. Consequences of this are likely to include the following:

- An increased respect for the field of sport psychology itself

- A greater emphasis on practical applications in specific sports

- Increased pressure on SPPs to have significant sport specific athletic experience of their own

Although the focus of this research paper has been on assessment in applied sport psychology, it is important to note that it is nearly always the case that application follows research. Advancements in medicine and new insight into the mind–body connection will likely increase the use of neurological, chemical, and physiological testing to help predict and influence performance. The ongoing search for strong ties between emotions and body chemistry may bring new kinds of SPPs to the field. For example, heart rate monitors and other biofeedback mechanisms are already being used to help athletes achieve optimal levels of arousal and to help SPPs better understand the competitive experience (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3 Assessment timeline.

FIGURE 3 Assessment timeline.

Bibliography:

- Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological testing. New York: Macmillan.

- Biddle, S. J. (Ed.). (1995). European perspectives on exercise and sport psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Duda, J. L. (Ed.). (1998). Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Fisher, A. C. (1984). New directions in sport personality research. In. J. M. Silva, & R. Weinberg (Eds.), Psychological

- foundations of sport (pp. 70–80). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Heil, J., & Henschen, K. (1996). Assessment in sport and exercise psychology. In J. Van Raalte, & B. Brewer (Eds.), Exploring sport and exercise psychology (pp. 229–255). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Nideffer, R. M., & Sagal, M. S. (2001). Assessment in sport psychology. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Orlick, T. (1990). In pursuit of excellence (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Ostrow, A. C. (1996). Directory of psychological tests in the sport and exercise sciences. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Scott, S. (2002). Fierce conversations. New York: PenguinPutnam.

- Silva, J. (1984). Personality and sport performance: Controversy and challenge. In J. Silva, & R. Weinberg (Eds.), Psychological foundations of sport (pp. 59–69), Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.