This sample Attention Deficit Disorders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with academic and social impairments that significantly compromise school performance. Effective school-based interventions include antecedent-based and consequent-based strategies that are implemented by teachers, peers, parents, computers, and/or the target students themselves.

Outline

- Description and Definition of Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder

- Conceptual Foundations of School-Based Interventions

- Interventions for Elementary School-Aged Students

- Conclusions and Future Considerations

1. Description And Definition Of Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, impulsivity, and/or overactivity. There are three subtypes of AD/HD: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive – impulsive, and combined type, with the latter being most common among clinic referrals and research participants. AD/HD affects approximately 3 to 5% of the school-aged population in the United States, with boys outnumbering girls by two to one in epidemiological samples and by six to one in clinic samples. The symptoms of AD/HD frequently are associated with impairment in academic, social, and behavioral functioning. The disorder tends to be chronic and often is a precursor to the development of other disruptive behavior disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Among the greatest long-term risks associated with AD/HD are scholastic underachievement, grade retention, and school dropout. The most effective treatments for this disorder include psychotropic medication, especially psychostimulants (e.g., methylphenidate), behavioral strategies applied at home and school, and (when necessary) academic interventions. It is assumed that most children with AD/HD will require a combination of these treatments to successfully ameliorate symptomatic behavior over the long term.

The most widely studied and used medications for AD/HD are central nervous system (CNS) stimulants such as methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, and Metadate), combined stimulant compounds (Adderall), and dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine). CNS stimulants are associated with improved attention and impulse control in the majority of treated children with AD/ HD. Side effects are benign in most cases, with insomnia and appetite reduction being the most common adverse effects. Behavioral effects vary considerably across individuals as well as across doses within individuals. Furthermore, stimulant medication effects are observed primarily during the school day because their duration of action ranges from 4 to 8 hours. For these reasons, it is important that information regarding behavior changes at home and school, as well as possible improvement or deterioration in academic performance, is taken into account when making medication decisions. For those individuals who do not respond to a CNS stimulant, alternative medications that may improve AD/HD symptoms include antidepressants (e.g., bupropion), antihypertensives (e.g., clonidine), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., atomoxetine).

2. Conceptual Foundations Of School-Based Interventions

There are several principles that are critical to the design of effective school-based interventions for students with AD/HD: gathering assessment data that directly inform intervention planning, implementing interventions at the point of performance, individualizing intervention strategies for each student, using a balanced treatment plan composed of both antecedent-based and consequent-based interventions, using strategies to address both academic and behavioral difficulties, and employing multiple individuals to implement treatment components.

2.1. Linking Assessment Data to Intervention

The assessment of children suspected of having AD/HD not only should be directed at establishing a diagnosis but also should provide data that can directly inform treatment planning. Thus, although norm-referenced measures such as behavior rating scales are helpful for making diagnostic decisions, additional measures should be included to provide information about possible directions for treatment. Specifically, functional assessment procedures, such as observations of target behaviors (e.g., calling out in class without permission) in the context of environmental events (e.g., classmates laughing), can be used. Data from a functional assessment can help to identify antecedents and consequences that may be maintaining a target behavior and that can be manipulated to change the frequency of a behavior. For example, disruptive behavior that consistently leads to peer attention as a consequence can be reduced by designing an intervention that provides the student with peer attention for engaging in appropriate behavior (e.g., peer tutoring).

2.2. Intervening at the Point of Performance

Because children with AD/HD typically exhibit poor impulse control, their behavior is more likely to be controlled by immediate environmental events than by long-term contingencies. For this reason, the most effective intervention strategies will be those that are implemented as close to the ‘‘point of performance’’ as possible. For example, if an intervention is necessary to reduce disruptive behavior occurring in math class and the latter is conducted from 9:00 to 9:45 AM each school day, the most effective interventions will be those that are implemented in math class from 9:00 to 9:45 AM. Treatment procedures that are removed in time and place from the point of performance (e.g., weekly counseling sessions in the school psychologist’s office) will be less effective.

2.3. Individualizing Intervention Strategies

Children with AD/HD exhibit a wide range of possible symptoms, disruptive behaviors, and academic difficulties. Thus, a ‘‘one size fits all’’ approach to treatment, wherein it is assumed that all students with AD/HD respond the same way to the same interventions, is likely to fail. The selection of intervention components should be made on the basis of individual differences in symptom severity, presence of comorbid conditions (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder), possible functions of the target behaviors, teacher acceptability of prescribed interventions, and empirical evidence supporting specific treatments for the target behaviors.

2.4. Combining Antecedent and Consequent Interventions

The application of both antecedent and consequent intervention strategies allows for students to have clear expectations of what is expected of them in advance (antecedent) as well as what will occur if problem behavior arises (consequent). Combining antecedent and consequent interventions also provides for more positive interactions and experiences, thereby potentially increasing the chances that the student will behave appropriately. Interventions based solely on aversive consequences or punishments often result in increased negative interactions between the student and the teacher and minimize the opportunity for positive reinforcement.

Antecedent or proactive intervention strategies are those that are implemented to prevent or preempt academic and/or behavioral difficulties from occurring. These could involve implementing classroom strategies and rule systems to provide structure, making environmental modifications (e.g., placing a child with academic or behavioral difficulties near the teacher or near children who are less likely to interact negatively with the child), having a child repeat instructions before beginning an assignment or activity, and/or providing limited task choices to a child prior to beginning seatwork.

Alternatively, consequent or reactive strategies are those implemented to respond to both appropriate and problem behavior when it does occur. An example of a consequent intervention might be a response cost system in which the student is ‘‘fined’’ for exhibiting problem behavior (e.g., loses points or reinforcement) yet also has the ability to earn and receive positive feedback when appropriate behavior is exhibited.

2.5. Combining Behavioral and Academic Interventions

Children with AD/HD often exhibit both academic and behavioral difficulties in the classroom. It is important to address both areas because a student who is frustrated academically may be more likely to exhibit negative behavior. Based on the results of a 1997 meta-analysis performed by DuPaul and Eckert on studies of school-based interventions from 1971 to 1995, improving a child’s academic skills may potentially improve his or her behavior in the classroom as well. In addition, targeting the attention difficulties associated with AD/HD and improving on-task behavior through behavioral intervention may potentially have a positive impact on academic skills. By including strategies targeting both academic skill areas as well as relevant behavior problems, teachers may be able to maximize the effectiveness of the interventions implemented. Collecting curriculum-based measurement and functional assessment data can lead to a better understanding of the factors contributing to academic and behavioral problems. Identifying the specific instructional needs and environmental variables that reliably proceed or follow inappropriate behavior can be a key component in the formulation of effective interventions.

2.6. Using Multiple Intervention Agents

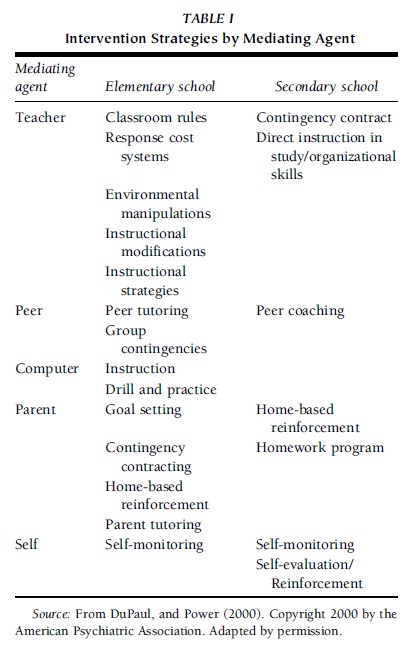

Effective intervention strategies can be implemented by a variety of mediating or intervention ‘‘agents.’’ Interventions can be mediated by teachers, peers, computers, parents, and/or the students themselves. By using multiple agents, sole responsibility for addressing all academic and behavioral difficulties associated with AD/HD does not fall on the teacher. Instead, multiple resources can be used to provide a more comprehensive, and potentially more cost-effective, method to support teacher instruction as well as to deliver interventions. Table I provides some possible intervention strategies listed by mediating agent. Specific intervention strategies organized by mediating agent and setting (elementary school vs secondary school) are discussed in more detail in later sections.

TABLE I Intervention Strategies by Mediating Agent

TABLE I Intervention Strategies by Mediating Agent

3. Interventions For Elementary School-Aged Students

As described previously, combinations of interventions appear to be most effective in improving and maintaining appropriate classroom behavior. This section discusses intervention strategies for improving academic and behavior performance using both antecedent and consequent intervention strategies across mediating agents. Typically, the most effective interventions include the use of multiple strategies and intervention agents.

3.1. Teacher-Mediated Strategies

Classroom strategies that have previously been found to be effective in improving the academic and behavior A response cost system requires a clearly defined rule system that is reviewed on a frequent basis. Within a response cost system, students may earn ‘‘tokens’’ (e.g., points, chips) for following rules and can lose tokens when rules are broken. The tokens can then be applied toward privileges such as taking the attendance to the office, passing out papers, and purchasing items from a ‘‘class store.’’ For a response cost system to be effective, students must have clear expectations of when the rules are in effect and what behavior will result in both the earning and losing of tokens. Examples of both situations should be given to confirm students’ understanding while the rules are being reviewed. Students should also understand what privileges are available, when they may exchange their tokens for privileges, and how many tokens are necessary for each privilege. Student motivation is a key component of an effective response cost system. Therefore, it may be beneficial to have students participate in a discussion of which privileges will be available and at what cost. It may also be helpful to determine ahead of time what privileges students are working for and to remind them periodically.

It is important to note that although class wide systems are widely effective for most students in the classroom, individual modifications may be necessary for those students whose behavior problems are more severe. If a student typically breaks 20 rules in a 30-minute class period, asking the student to break only 2 rules may be an unrealistic expectation and the child may be unmotivated by the system. Therefore, the amount of tokens necessary to earn a privilege might need to be altered on an individual basis. Similarly, if students can earn points for following rules for a certain amount of time, it might be necessary to decrease the required duration for specific students to allow them to earn points. Adjusting the time period also provides for more immediate feedback to those students who might need more frequent reinforcement.

In addition to classroom rules and response cost systems, children with AD/HD may benefit from alterations to the classroom environment to allow for increased monitoring of classroom behavior. Children with AD/HD may benefit from being placed near the teacher or with peers who are less likely to interact negatively with them. In addition, although it may seem advantageous to place children with severe attention and behavior difficulties in isolated areas of the classroom, it is important that they remain a part of important classroom activities and have access to teacher instruction and positive peer interactions.

Behavior and academic difficulties often associated with AD/HD may be exacerbated by instructional demands that are too high for students’ current level of functioning. Frustration with tasks that are too difficult may increase the likelihood that some children will exhibit negative behaviors. Thus, it is important to assess and adjust academic expectations to match a student’s current skills or instructional level. Curriculum-based measurement (CBM) data may be a helpful tool for teachers to determine the appropriate level of instruction that a child should receive. CBM can also provide information as to areas in which a child might need additional instruction and academic intervention. Instructional modifications and interventions for children may include direct instruction in particular skills that a child is lacking as well as drill and practice activities such as flashcard drills and structured worksheets.

Students with attention or behavior difficulties may also benefit from being provided with choices in academic tasks within a particular academic area. For example, students may be provided with a menu of acceptable tasks for a particular subject from which to choose. For this strategy, the teacher offers a menu of tasks that he or she finds acceptable, and the student chooses one to complete during the time allotted. The menu and choice component allows for both the teacher and the student to maintain control over the work completed. Thus, providing choices in academic tasks may increase the student’s work productivity and on-task behavior.

3.2. Peer-Mediated Interventions

Peers working together on an instructional activity can also have a positive impact on the academic engagement and performance of students with AD/HD. In addition, peer tutoring strategies, by targeting academic instruction through peer interaction, are able to address both academic and social skills simultaneously. Because children with AD/HD have often been found to have difficulty in both areas, peermediated strategies can be a particularly useful tool.

Although different peer-mediated strategies vary regarding their foci of instruction and the structure and procedures of the tutoring teams, Barkley’s 1998 handbook for diagnosis and treatment of AD/HD listed the following four common characteristics that have been shown to enhance task-related behaviors of children with AD/HD: (a) working one-on-one with another individual, (b) letting the learner determine the instructional pace, (c) continually prompting academic responses; and (d) providing frequent immediate feedback about quality of performance.

In 2002, Greenwood and colleagues described peer tutoring as an instructional strategy in which classroom teachers train and supervise students to teach their peers. Peer-directed instruction allows for high levels of student engagement, sufficient practice, immediate error correction and feedback, and the integration of students with varying abilities. In their review of peer tutoring strategies, Greenwood and colleagues described four programs that have been found to have well-defined procedures and supporting evidence in the research for use with students with disabilities: Classwide Peer Tutoring (CWPT), Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS), Classwide Student Tutoring Teams (CSTT), and Reciprocal Peer Tutoring (RPT).

3.3. Computer-Assisted Interventions

Computer-assisted interventions (CAI) can be an effective tool for promoting skill acquisition through the use of instructional technology as well as for providing additional drills and practice to promote mastery of previously acquired skills. Features of computer programs (e.g., provision of immediate performance feedback) may be able to positively affect on-task behaviors and work production of children with AD/ HD. In 2003, DuPaul and Stoner listed the following important design features of CAI that may be beneficial for children with AD/HD: specific instructional objectives presented along with activities, use of print or color to highlight important material, use of multiple sensory modalities, content divided into manageable sized chunks of information, the ability to limit nonessential distracting features (e.g., sound effects, animation), and immediate feedback on response accuracy.

3.4. Parent-Mediated Interventions

Parents should also be considered a valuable resource in promoting the academic success of their children. Frequent and clear communication between teachers and parents provides parents with knowledge about their children’s academic and classroom-related behaviors and also provides teachers with information regarding events at home that may affect classroom behavior and performance. Parents can then support and reinforce instruction in the classroom as well as help to promote appropriate classroom behavior.

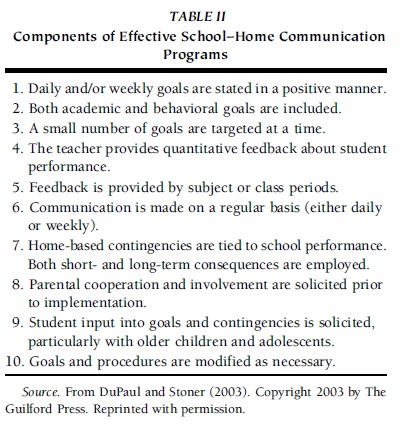

Parents, in providing instructional support to their children, can engage their children in flashcard drills for additional practice in an area, act as tutors to aid in skill acquisition, and make themselves available for homework support. Many parents may already participate in similar activities or would like to participate but are unsure as to how they can be most helpful. A key component to effective instructional support at home is parents’ knowledge regarding instruction that their student, should generally consist of areas of primary concern for the student, and should be stated in a positive manner. Some examples of classroom goals may include participation in class discussions, appropriate interactions with peers, work completion, and accuracy. Goals can be rated on a yes/no scale (e.g., appropriately participates in class discussion two times, completes work with 85% accuracy) or on a range of scores (e.g., a 5-point scale ranging from ‘‘excellent’’ to ‘‘terrible’’). The report card ratings should be filled in by each teacher (in ink to prevent alterations by students) and carried from class to class by students. At home, scores on the report card can then be used in a token economy to be exchanged for privileges or points to be applied to later privileges (e.g., television time, computer time, later bedtime). Table II lists components of effective school–home communication programs.

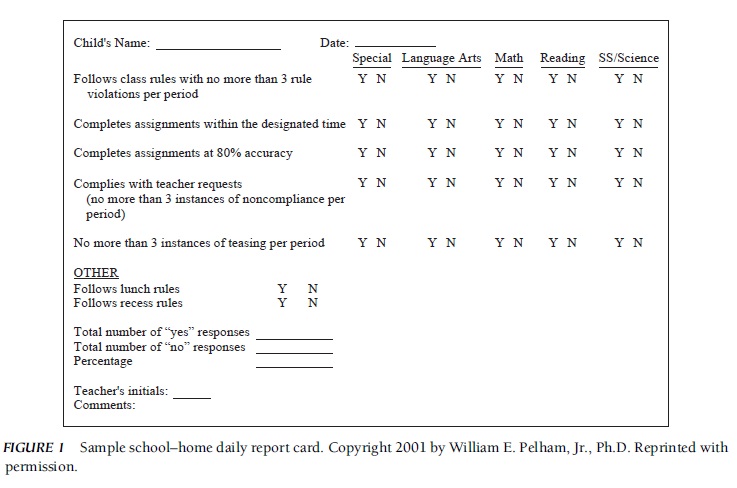

As with classroom-based response cost systems, students should be aware of specific criteria necessary to earn privileges, which privileges they can work toward, and when they may exchange tokens for them. Exchanges for privileges might need to occur on a more frequent basis during the initial stages of a school–home contingency system and should be adapted based on the age and developmental level of each student. Motivation of the students is vital to the success of the school–home contingency system. Therefore, it may be beneficial for students to have input into goals and privileges. In addition, a space for teacher comments and parent signatures can be provided to allow for frequent brief communications between parents and teachers. Figure 1 shows an example of what a school–home daily report card might look like.

TABLE II Components of Effective School–Home Communication Programs

TABLE II Components of Effective School–Home Communication Programs

3.5. Self-Mediated Interventions

Students can also be taught to monitor their own behavior or completion of academic-related steps. Although each student acts as the primary mediator for such strategies, it is important to note that a teacher must be present to signal recording and/or to monitor the accuracy of the student’s self-recording. Checklists for work completion, or for procedures for completing tasks in specific academic areas, can be created. The presence of these checklists while the student is completing work can provide a prompt as to what steps are necessary to complete the task as well as provide for communication between the teacher and the student as to what steps have been completed.

Students can also be taught to observe and record occurrences of their own behavior—both positive and negative. A checklist or grid can be provided for each student to keep on his or her desk. The student could then record occurrences of a behavior or be taught to respond to a signal (e.g., a beep from a tape recorder) and record whether or not he or she is currently performing a specific behavior (i.e., on task) at that time. In this way, not only is the student monitoring the occurrence of his or her own behavior, but the signal also acts as a prompt to demonstrate the behavior. To be most effective, it might be advantageous to have the teacher also record occurrences. These records can then be ‘‘matched’’ and reinforcement can be provided based on how well the results from the teacher and the student match up. Frequency of teacher–student match checks and reinforcement schedules can then be decreased as the child becomes more adept at the procedures.

3.6. Intervention Considerations for Secondary School-Aged Students

Typically, AD/HD symptoms are chronic and can be associated with myriad additional difficulties for secondary school-aged students. Adolescents with AD/HD often exhibit problems with study and organizational skills, test performance, and social and emotional adjustment. Unfortunately, minimal research has been conducted examining school-based interventions for secondary-level students with this disorder. Although many of the interventions discussed for children with AD/HD may be helpful for adolescents, modifications must be made to account for expected differences in developmental level and degree of independence. For example, token reinforcement and/or response cost systems must be modified in several ways. First, the adolescent should be involved in ‘‘negotiating’’ the specific responsibilities and privileges that are included in the contingency management system. Second, the system will be less concrete than what typically is used with younger children. In particular, a written contract specifying reinforcement and punishment is used rather than token reinforcers such as stickers and poker chips. Third, the time period between completion of a responsibility and receipt of reinforcement might be longer than with younger children because adolescents are presumably able to handle longer delays in reinforcement. As is the case for younger students, interventions for adolescents with AD/HD should include a variety of mediators (e.g., teachers, parents, computer, peers, self), especially because secondary school students have multiple teachers who might not have the time to implement complex treatment protocols. Self-mediated interventions have particular promise for those adolescents who have demonstrated progress with other-mediated strategies and who appear to have the requisite skills for self-monitoring and self-evaluation.

FIGURE 1 Sample school–home daily report card.

FIGURE 1 Sample school–home daily report card.

In addition to the various interventions enumerated previously, secondary school students with AD/HD may require other interventions to address study and organizational skills deficits as well as difficulty in interacting with peers and authority figures. First, students can be provided with direct instruction in study and organizational skills, including taking notes, preparing for and taking tests, and completing long-term assignments. A second promising avenue for intervention for adolescents with AD/HD is the implementation of ‘‘coaching’’ to support students in achieving self-selected academic, behavioral, and social goals. Peers, older students, siblings, or adults can serve as coaches for students, who are assisted in setting goals, developing plans to reach stated goals, identifying and overcoming obstacles to goal attainment, and evaluating progress. Third, adolescents with AD/HD and their families are likely to require some form of counseling support to address possible difficulties in adherence with household rules as well as in interactions with family members. Support may include promoting an accurate understanding of AD/HD and its influence on families’ interaction patterns; planning the education of adolescents with AD/HD; and/or negotiating privileges and responsibilities.

4. Conclusions And Future Considerations

Children and adolescents with AD/HD frequently experience difficulties in school settings, most notably in the areas of academic achievement and interpersonal relationships. Thus, a comprehensive treatment plan often includes a variety of school-based interventions in combination with psychostimulant medication and home-based behavioral strategies. Effective classroom interventions include both proactive strategies that are designed to modify antecedent events and reactive strategies that focus on changing consequent events. Although treatment strategies are usually implemented by teachers, plans should include peer-mediated, self-mediated, computer-mediated, and/or parent-mediated components. Interventions that directly address the function of disruptive behavior and that are applied as close to the point of performance as possible are more likely to be effective. Students with AD/HD at the secondary school level will require additional support to enhance study and organizational skills as well as coaching to improve social relationships. Empirical investigations conducted to date have emphasized the use of reactive, consequent-based interventions. Research efforts must be directed toward establishing efficacious, antecedent-based strategies as well as toward providing more support for interventions to address the unique needs of secondary school-aged students with this disorder.

References:

- Barkley, R. A. (1998). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

- Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (1998). Coaching the ADHD student. New York: Multi-Health Systems.

- DuPaul, G. J., & Eckert, T. L. (1997). School-based interventions for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 26, 5–27.

- DuPaul, G. J., & Power, T. J. (2000). Educational interventions for students with attention-deficit disorders. In T. E. Brown (Ed.), Attention-deficit disorders and comorbidities in children, adolescents, and adults (pp. 607–635). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- DuPaul, G. J., & Stoner, G. (2003). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

- Goldstein, S., & Goldstein, M. (1998). Managing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: A guide for practitioners (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley.

- Greenwood, C. R., Maheady, L., & Delquadri, J. (2002). Classwide peer tutoring programs. In M. R. Shinn, H. M. Walker, & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventative and remedial approaches. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

- Pelham, W. E. (2001). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis, nature, etiology, and treatment. (Available: Center for Children and Families, 318 Diefendorf Hall, 3435 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14214)

- Pelham, W. E., Wheeler, T., & Chronis, A. (1998). Empirically-supported psycho–social treatments for ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 190–205.

- Rathvon, N. (1999). Effective school interventions: Strategies for enhancing academic achievement and social competence. New York: Guilford.

- Robin, A. L. (1998). ADHD in adolescents: Diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford.

- Shapiro, E. S., & Cole, C. L. (1994). Behavior change in the classroom: Self-management interventions. New York: Guilford.

- Shinn, M. R. (Ed.). (1998). Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guilford.

- Watson, T. S., & Steege, M. W. (2003). Conducting school-based functional behavioral assessments: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.