This sample Attitudes Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Attitudes are the relatively enduring evaluations that people hold toward all sorts of things in the world. Attitudes can be held toward people, objects, issues, and concepts. Researchers have devoted a great deal of effort to understanding attitudes because attitudes have been shown to be useful in predicting human behavior. Because of this interest, researchers have developed theories to explain where attitudes come from and tools with which to measure attitudes. Some research has focused on the distinctions between strong and weak attitudes, whereas other research has examined how attitudes can be changed. Because they are such an important part of everyday life, attitudes are one of psychology’s most important constructs.

Outline

- Introduction

- The Tripartite Model of Attitudes

- Attitude Measurement

- Attitude Strength

- Attitude Change

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

A college student may like her psychology course but dislike her literature course. A consumer may prefer liquid laundry detergent over the powdered variety. And a city’s populace may prefer the incumbent mayor over the challenger. Liking and disliking the objects in our world is a fundamental part of human nature. Psychologists use the term ‘‘attitude’’ to refer to these likes and dislikes that people hold—the relatively enduring evaluations that people hold toward all sorts of things. We can hold attitudes toward people (e.g., friends, celebrities), objects (e.g., automobiles, candy bars), political or social issues (e.g., capital punishment, immigration policy), and even abstract concepts (e.g., conservatism, democracy).

For years, researchers have spent a great deal of effort in attempting to better understand attitudes. One of the reasons why the concept has attracted so much attention is that attitudes serve an important role in our daily lives. The attitudes of college students influence which courses they decide to attend, the attitudes of consumers guide their decisions about which products to purchase, and the attitudes of a city’s population affect voters’ decisions about which candidate to elect. It is obvious that human behavior has a variety of causes, but understanding a person’s attitudes is often a reliable way in which to predict the person’s behavior. But attitudes also serve other roles. Sometimes, attitudes help us to gain rewards and avoid punishments. Other times, attitudes help us to define who we are as people; people may feel so strongly about an attitude that they define themselves in terms of that attitude (e.g., people may consider themselves to be ‘‘staunch Democrats’’ or ‘‘hardcore pro-lifers’’). In addition, some research has even shown that holding negative attitudes toward other people may make us feel better about ourselves. Thus, because the attitudes we hold play important roles in many arenas, they are indeed a fundamental part of our everyday lives.

2. The Tripartite Model Of Attitudes

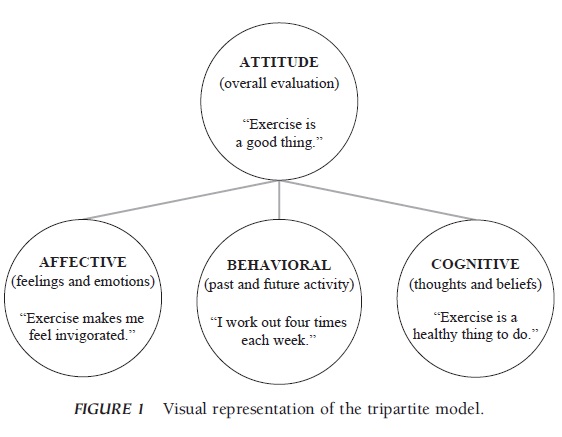

Where do attitudes come from? Research on the tripartite model of attitudes suggests that attitudes can be based on three different sources (for a visual representation of the tripartite model, see Fig. 1). One part of the tripartite model is the affective component. This affective basis of attitudes refers to the feelings, moods, and emotions that are associated with the attitude object. Consider a person who likes to exercise—a person who could be said to have a positive attitude toward exercise. This person’s feelings of being ‘‘invigorated’’ or ‘‘distressed’’ whenever he or she exercises could serve as the affective basis of the attitude. Next, the behavioral basis refers to how the person has acted or would act in the future in regard to the target. If the person visits the gym to work out four times per week, this activity would serve as the behavioral basis. Finally, the cognitive basis refers to the overt thoughts or beliefs that the person has in regard to the target. If the person thinks that exercise is ‘‘healthy’’ and ‘‘worthwhile,’’ such thoughts would serve as the cognitive component of the attitude.

In this example, the affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of the attitude all are positive, and this would suggest that the person will likely hold an overall positive attitude toward exercise, that is, the attitude object. However, the three components will not necessarily be consistent. A person may think that chocolate cake tastes wonderful (affective) and may eat chocolate cake often (behavioral) but may also think that chocolate cake is loaded with calories and fat (cognitive). In such cases, the overall attitude toward the object may be based more heavily on some components than on others.

It is important to note, however, that the components of attitudes can also be influenced by the attitude itself.

FIGURE 1 Visual representation of the tripartite model.

FIGURE 1 Visual representation of the tripartite model.

For example, in 1993, Eagly and Chaiken discussed how the attitude can also influence the three components. In other words, a person’s affect, behaviors, and cognitions not only may guide and create the attitude but also may be driven or influenced by the attitude. As such, the three components of the tripartite model can be conceptualized in terms of both antecedents and consequences of their associated attitudes.

3. Attitude Measurement

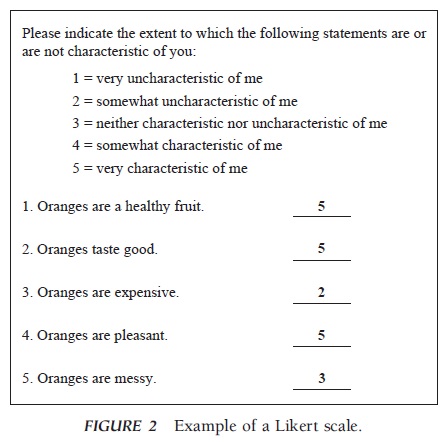

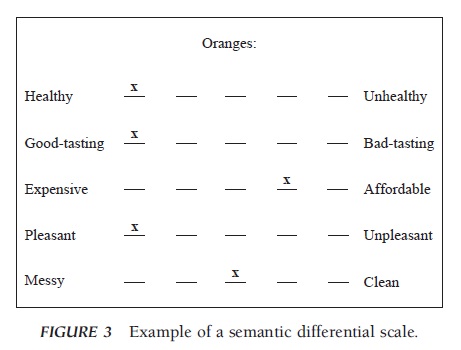

Because attitudes are so important, researchers have developed a variety of tools with which to measure them. Two of the most commonly used techniques are the Likert scale and the semantic differential. As shown in Fig. 2, participants reporting attitudes on a Likert scale are asked to what extent a variety of statements are characteristic of them. In a similar vein, as shown in Fig. 3, participants reporting attitudes on a semantic differential measure are asked to indicate how well a series of adjectives describe the attitude object. In either case, the researcher will typically provide a variety of items for the participant to complete. The scores from the items are combined to create an overall measure of the person’s attitude toward the target.

Because attitudes are so important, researchers have developed a variety of tools with which to measure them. Two of the most commonly used techniques are the Likert scale and the semantic differential. As shown in Fig. 2, participants reporting attitudes on a Likert scale are asked to what extent a variety of statements are characteristic of them. In a similar vein, as shown in Fig. 3, participants reporting attitudes on a semantic differential measure are asked to indicate how well a series of adjectives describe the attitude object. In either case, the researcher will typically provide a variety of items for the participant to complete. The scores from the items are combined to create an overall measure of the person’s attitude toward the target.

There are several guidelines that researchers can follow in attempting to tap a person’s attitude with as little error as possible. One guideline is to reverse code some of the items by framing them negatively as done in the third and fifth items in Figs. 2 and 3. Doing so serves two purposes. First, it reduces the likelihood that a person will simply check the leftmost or rightmost box down the entire instrument in attempts to save time or cognitive resources. A person is less likely to do so if he or she realizes that various items are indeed reverse coded. Similarly, if a person does simply check the leftmost or rightmost box down the entire instrument, the researcher may recognize this and treat the data accordingly. Also, some research suggests that providing respondents with five to seven options from which to select provides the most valid data. Scales with fewer than five options lack the precision necessary to measure attitudes accurately, whereas scales with more than seven options tend to suffer from additional noise without benefiting from any additional precision.

FIGURE 3 Example of a semantic differential scale.

FIGURE 3 Example of a semantic differential scale.

Likert scales and semantic differential scales are ubiquitous. Students typically use Likert scales when evaluating their professors at the end of a semester, and departments and universities use these data in part to make personnel decisions. Companies also use such techniques to measure customers’ attitudes toward the products and/or services the companies offer. By learning which aspects of the companies customers like and dislike, managers can direct resources to improve deficient areas of their companies. In short, proper attitude measurement can gauge the likes and dislikes of a person or a group of people. Behavior of a person or a group of people can then be predicted based on the attitude measure.

4. Attitude Strength

Although attitudes typically predict behavior, this is not always the case. Some attitudes have tremendous influence over our lives, whereas others are largely inconsequential. For example, consider two people’s attitudes toward environmental protection. The two people both may think that protecting the environment is a good thing—they both may hold positive attitudes toward environmentalism—but the strength of those attitudes may be quite different. One person’s attitude may lead her to vote only for pro-environment candidates, drive a fuel-efficient car, and donate money to pro-environment organizations. On the other hand, the other person’s attitude may have very little impact. He will occasionally recycle and has on occasion voted for pro-environment candidates. Why would two people who hold equivalent attitudes act so differently?

The difference lies in attitude strength. In 1995, Petty and Krosnick defined attitude strength as the extent to which an attitude persists over time, resists change when exposed to persuasive information, influences cognitive processes, and influences behavior (as in the preceding example). Although two people may hold what appear to be equivalent attitudes—perhaps as observed by identical scores from Likert scales— the attitudes might not be functionally equivalent. Researchers have identified a wide variety of ways in which attitudes can become stronger, including thinking about attitudes, learning about the attitude object, or expressing attitudes repeatedly.

Attitude strength can be measured by observing the four defining features directly: how long attitudes persist over time, how well attitudes resist persuasive attempts, the extent to which attitudes predict cognitive processes, and the extent to which attitudes predict behavioral processes. But there is a wide variety of other features that are associated with these defining features. Some researchers have investigated the certainty with which attitudes are held: when a person feels certain of an attitude, that attitude is likely to show the four defining features of attitude strength. In a similar vein, researchers have shown that accessible attitudes, attitudes based on much knowledge, and attitudes on issues that people find to be personally important also tend to manifest the four defining features of attitude strength.

Therefore, many researchers measure not only attitudes but also the strength of those attitudes. For example, consider an incumbent governor’s campaign manager determining in which counties to invest scarce advertising funds. Although two counties may show roughly equivalent positive attitudes toward the incumbent, such a report tells only part of the story. Based on this information alone, the manager might decide to split the advertising dollars across both counties equally. However, it is possible that the citizens of County A may be, on average, highly certain of their positive attitudes, whereas the citizens of County B may be, on average, not certain at all. In such a case, one would expect that the positive attitudes would predict vote choice better among the residents of County A than among those of County B. Therefore, the manager would benefit more from investing advertising in the county with the weaker attitudes (as measured by certainty) than in the county with the stronger attitudes. Thus, measuring attitudes alone is only part of the story. One must also measure the strength of those attitudes to predict the behavioral and cognitive consequences of attitudes most effectively.

5. Attitude Change

Attitudes are thought to be relatively enduring evaluations. However, there is a wealth of research on how attitudes can and do change in the face of a persuasive communication. One of the most widely studied theories of persuasion is Petty and Cacioppo’s elaboration likelihood model. In their 1986 research paper, these researchers posited that there are two routes through which persuasion can take place. When people have the motivation and the ability to carefully process and think about the arguments within a counter attitudinal message, they will use the central route to persuasion. When people process messages centrally, they evaluate the arguments within the message—the logical factual information that is directly relevant to the attitude object. People will then change their attitudes to the extent that their cognitive responses—the thoughts they have about the arguments while reading the message—are positive. However, when people lack either the motivation or the ability to carefully process and think about the arguments within a counter attitudinal message, they will use the peripheral route to persuasion. When people process a message peripherally, instead of elaborating on the arguments within the message, they respond to cues that exist within the message— images or heuristics not directly relevant to the message that can persuade without requiring much thought.

For example, consider an advertisement for a new car that appears in a general-interest magazine. At the top of the advertisement is the name of the car, and at the bottom of the page are three paragraphs detailing the car’s resale value, horsepower, gas mileage, and safety record. In the background is an image of the car being driven across a sun-drenched beach with beautiful palm trees swaying in the background. A reader who is in the market for a new automobile may have the motivation to use the central route to persuasion when processing the advertisement. This person will carefully read the arguments at the bottom of the page and, assuming that the reader’s cognitive responses are positive, will end up with a more positive attitude toward the car. However, consider another reader who does not plan to purchase a car for years and therefore has no motivation to use the central route. This person may instead simply observe the beautiful palm trees and the beach and therefore simply create an association between the positive imagery and the car. Thus, the second person may also end up with a more positive attitude toward the car but will do so through the peripheral route instead of the central route. If both the central and peripheral routes can lead to the same effect (e.g., attitude change), why does it matter which route to persuasion people take? Perhaps the most important reason is that attitudes resulting from central route persuasion tend to be stronger than attitudes resulting from peripheral route persuasion. That is, attitudes formed from central route processing tend to be more persistent over time, more resistant to future persuasion, and more impactful on behavior and cognitive processes than do attitudes formed from peripheral route processing. So, from this standpoint, it would seem better to engage an audience in central route processing due to the enhanced strength that would result. However, peripheral route processing may be the best option when (a) the audience does not have the ability or motivation to use the central route or (b) there are very few compelling arguments that can be presented in a message in the first place. In short, persuasion practitioners must balance the costs and benefits when determining whether to use primary central route or peripheral route persuasive appeals.

6. Conclusion

Attitudes, as the representations of what we like and dislike, play an important role in our daily lives. From important decisions such as choosing one presidential candidate over another to more mundane decisions such as which flavor of ice cream to purchase, attitudes play a fundamental role in all sorts of behavioral and cognitive processes. Because they are such an important part of our lives, they have all sorts of important applications. Political scientists study attitudes in attempting to predict voters’ choices, consumer psychologists study attitudes in attempting to understand consumers’ purchasing decisions, and health promotion researchers study attitudes in attempting to understand the healthy and unhealthy behaviors in which people engage. In short, because they play a fundamental role in explaining behavioral and mental processes, attitudes are one of psychology’s most important constructs.

References:

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 269–322). New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24, 163–204.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205.

- Petty, R. E., & Krosnick, J. A. (Eds.). (1995). Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Lieppe, M. R. (1991). The psychology of attitude change and social influence. New York: McGraw–Hill.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.