This sample Behavioral Medicine Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples. This sample research paper on behavioral medicine features: 8200+ words (30 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 5 sources.

Behavioral medicine is an emerging specialty. The Society of Behavioral Medicine defines the field as ‘‘the interdisciplinary field concerned with the development and integration of behavioral and biomedical science knowledge and techniques relevant to the understanding of health and illness, and the application of this knowledge and these techniques to prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation.’’ Several characteristics of this definition are particularly important. First, the definition recognizes the need for collaboration between physicians, biomedical scientists, and behavioral scientists. Efforts of psychologists without medical collaborators, or by physicians without behavioral collaborators, have less potential. Second, the definition stresses the application of behavioral knowledge to problems in physical health. Physical health has not traditionally been within the domain of psychology. Third, the definition excludes the more traditional topics of clinical-abnormal psychology, such as psychosis and neurosis. Although some behavioral medicine specialists study substance abuse, they tend to study traditional psychological problems only insofar as they contribute to physical health. Reflecting the view that mental and physical functioning are closely related, the biopsychosocial model of health and illness is endorsed by many practitioners of behavioral medicine. According to this model, health status is determined by multiple factors. The traditional medical model generally views specific biological factors as causing most health problems. Within the biopsychosocial model, psychological factors (thoughts, behaviors, feelings) and social factors are treated as equally important contributors to many health states.

Outline

I. Distinctions between Health Psychology, Behavioral Medicine, and Psychosomatic Medicine

II. Examples of Basic Research in Behavioral Medicine

A. Psychoneuroimmunology, Stress, and Health

B. Cardiovascular Reactivity

C. Personality and Illness

III. Examples of Behavioral Medicine in Clinical Practice

A. Treatment of Heart Disease

B. Adaptation to Cancer

C. Functioning in Lung Disease

IV. Behavioral Medicine in Public Health

A. Epidemiology

B. Behavioral Epidemiology

1. Tobacco

2. Physical Activity

C. Prevention Sciences

D. Health Care Policy

V. Summary

I. Distinctions between Health Psychology, Behavioral Medicine, and Psychosomatic Medicine

Health psychology is the umbrella term for a variety of topics related to the interface between psychology and medicine. The Division of Health Psychology of the American Psychological Association defines its specialty as ‘‘the aggregate of the specific educational, scientific, and professional contributions of the discipline of psychology, to the promotion and maintenance of health, the prevention and treatment of illness, and the identification of the etiologic and diagnostic correlates of health, illness, and related dysfunction.’’

The field of behavioral medicine regards the status of medical and behavioral collaborators to be equal, with neither participant taking the dominant role. In contrast to health psychology, which emphasizes work done by psychologists, behavioral medicine emphasizes work that is collaborative between biomedical and behavioral scientists. One distinction between behavioral medicine and health psychology is that behavioral medicine is a collaboration of behavioral and medical scientists to improve health, and health psychology is the unique contribution of psychologists to this process.

II. Examples of Basic Research in Behavioral Medicine

Behavioral medicine encompasses a very diverse field of research. It would be impossible to review the entire domain within this research paper. Instead, we will highlight a few key research areas to provide an overview of the kinds of questions with which researchers struggle.

A. Psychoneuroimmunology, Stress, and Health

There exists a long legacy of contradictory and sometimes confused thinking regarding the relationship between mind and body. At one time, the idea that external events and stressful situations could adversely impact health was not accepted by the medical establishment. Those who believed in such a connection could offer no plausible biological mechanism. For such a relationship to be possible, the relationship between the nervous system and the immune system must be understood. These systems are known to interact through two major pathways: the autonomic nervous system and the pituitary-regulated neuroendocrine outflow. A central focus of behavioral medicine research has been to elucidate the nature of the relationship between stress and health status. The field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) examines the effects of stress on health and disease processes, primarily as mediated by the immune system. A number of studies have demonstrated that stress may reduce immune system functioning, in both animals and humans.

To understand psychoneuroimmunology, it is important to understand how the immune system works. The immune system is made up of many different structures—cells (lymphocytes), tissues, and organs (e.g., thymus gland, spleen)—that communicate with each other through the bloodstream and lymphatic system. There are two major types of cells, T- and B-lymphocytes. T-cells include helper cells, which tell the immune system to ‘‘turn on’’ in the face of a virus or other invader, and suppressor cells, which tell the system to slow down.

Some PNI researchers ask a basic, but often elusive, question: How does the nervous system interact with the immune system at the cellular level? Recently, they have discovered that lymph nodes (which are made up of lymphocytes) receive neural input from the sympathetic nervous system. (The sympathetic nervous system is also sometimes called the ‘‘fight or flight’’ system.) Other researchers have found that many lymphocytes have special sites that act as receptors for neurotransmitters. Because of these and related discoveries, we now know that the nervous system exerts considerable influence on the activities of the immune system. And the reverse also seems to be true: alterations in immune functioning have been found to affect the activity of neurons in brain areas such as the hypothalamus.

A recent meta-analysis examined the literature on the relationship between stress and immunity in humans. The analysis found that increased stress is reliably associated with higher numbers of circulating white blood cells, and with lower numbers of circulating T- and B-lymphocytes. Increased stress is also linked to decreased levels of immunoglobin, another measure of immune status. Finally, stress was associated with increases in antibodies against the virus that causes herpes.

In one example of a stress immunity study, several immune parameters in 75 first-year medical students were assessed 1 month before final examinations and again at the start of final examinations. Immune cell activity was significantly lower at the (presumably higher stress) time of the examination than it had been a month earlier. In another study, immune status was assessed in 38 married and 38 separated or divorced women. Poor marital quality in the married group and shorter separation time in the second group were associated with poorer functioning on several immune measures.

It is important to note that there are still many unanswered questions about psychoneuroimmunology. Despite the clear relationship between stress and immune status, a solid link between stress and increased rates or duration of disease has been found with much less consistency. One reason for this shortcoming is the relatively low rate of specific poor health outcomes among a healthy population. A few studies have attempted to circumvent this incidence barrier, with some success.

One disease that is relatively easy to study is the common cold. Unlike major diseases such as cancer or heart disease, the common cold can be induced by experimenters with little risk of long-term consequences. In one intriguing study, researchers exposed 357 healthy participants to either a cold virus or a placebo. Higher rates of colds and respiratory infections were associated with higher levels of psychosocial stress.

Other studies of the psychoneuroimmunology of infectious diseases have been conducted, most notably with HIV. Although findings have been mixed, several studies have demonstrated improvement in immune parameters following behavioral or psychological interventions.

Many other issues exist in the study of psychoneuroimmunology. Debate continues, for example, on how best to define stress. Some researchers focus on objective, negative life events such as bereavement, whereas others use self-reported stress levels. Available research indicates that using objective events as the independent variable provides more consistent immunosuppressive results. Other remaining problem areas include achieving a better understanding of the immune effects of specific stressors, the role of stress duration in immune response, and the personal characteristics that make some individuals less susceptible than others to the immune effects of stress.

How people perceive stress, how they cope with stress, and how their social environment affects their reaction to stress may also explain some discrepant findings. In fact, inadequate coping in the face of marked adversity is often part of the definition of stress. According to this argument, stressful events will induce a stress response only if the organism cannot, or believes it cannot, cope with adversity. Thus, an organism’s coping attempts may be an important variable in the stress–health relationship. One study found, for example, that stress with academic examinations may be more immunosuppressing among individuals who react with much more anxiety compared with those who do not. One longitudinal study of patients with metastatic breast cancer (in which the cancer has spread beyond the breast tissue) found that long-term survivors appeared to be more able to externalize their negative feelings and psychological distress through the expression of anger, hostility, anxiety, and sadness. Those who survived only a short time tended to be those individuals whose coping styles involved suppression or denial of psychological distress.

A relationship between suppression of emotion and poor cancer outcome has been noted with enough regularity that some researchers have identified a cancer-prone ‘‘Type C’’ personality that has as a main element exaggerated suppression of negative emotions like anger. In one study of women undergoing breast biopsies, women who were subsequently diagnosed with breast cancer had significantly higher levels of emotion suppression than did women who did not have cancer. Other studies have replicated these results. Because these women already had cancer, however, it was not possible to establish the causal relationship between suppression of emotion and breast cancer.

As the putative link between stress and immune functioning has gained more support, researchers have turned to interventions aimed at ameliorating the detrimental effects of stress. Relaxation training, long used in mental health contexts, was associated in one study with increased immune activity in an elderly population. Other stress control interventions, such as biofeedback and cognitive therapy, have been found in some studies to exert a beneficial influence on immune status.

B. Cardiovascular Reactivity

Because cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, many behavioral medicine researchers study factors that may influence the course of this disease. Many studies focus on the effects of diet and exercise changes on cardiovascular health. Other researchers study a phenomenon known as cardiovascular reactivity. We describe some of this research in the following section.

Not all people respond to stressors in the same way. In general, being exposed to a stressor causes a rise in blood pressure. Some people react to a stressor with a relatively small rise in blood pressure, whereas for others the rise is very large. Behavioral medicine researchers have been interested in the question of whether large blood pressure increases in response to a stressor are risk factors for developing hypertension (high blood pressure), and whether these changes predict heart attack, stroke, and death. Researchers are also attempting to determine whether individual, potentially modifiable factors such as personality are related to this hyper-reactivity. Studies examining the predictive power of reactivity have had mixed results. Some studies have found that cardiovascular blood pressure reactivity in childhood predicts the development of hypertension up to 45 years later. Other studies, however, have failed to find any relationship.

Researchers have examined reactivity in adulthood to predict who is most at risk for developing future vascular disease. In one well-known study, researchers attempted to identify risk factors for developing future cardiovascular disease. They found that many factors, such as resting blood pressure, smoking, and cholesterol level, were all predictive of who died from the disease 23 years later. More predictive than those variables, however, was subjects’ response to a cold-presser task. The cold-presser task requires subjects to immerse a hand in ice water. Subjects are exposed for a specific time and their blood pressure is recorded. In this study, subjects who had the largest increase in blood pressure in response to the task were most likely to die from cardiovascular disease in the future.

Several factors limit our confidence in reactivity research. Notably, laboratory stressors are not the same as real-world stressors. Therefore, it has been a goal of researchers to measure blood pressure in response to stressors that individuals experience in their daily lives. Recently, the development of ambulatory blood pressure monitors has made it possible to monitor the blood pressure of an individual throughout the day. Participants can keep diaries of stressful events, and researchers can examine how blood pressure varies in response to these stressors. Clinically, this technique could eventually allow for improved risk prediction for at-risk individuals.

Researchers are currently attempting to answer several puzzling questions about cardiovascular reactivity. For instance, the physiological mechanism linking hyperreactivity to undesirable health outcomes is not known. Studies have also failed to determine the cause of hyperreactivity. Is it simply a genetic phenomenon? Or are there environmental factors at work? If the cause is environmental, researchers may be able to develop treatments for hyperreactivity. Such interventions have the potential for reducing the number of people who die each year from cardiovascular disease.

C. Personality and Illness

Another major focus of behavioral medicine research is the relationship between personality factors and illness. Interest in this relationship dates back at least to the ancient Greeks, who classified people into one of four basic personality types (phlegmatic, melancholic, sanguine, and choleric); these personalities were presumed to be based on imbalances in bodily fluids, or humors. Early in this century, it was believed that certain diseases, such as hypertension, heart disease, cancer, asthma, ulcerative colitis, and ulcers, were ‘‘psychosomatic’’—mainly caused by personality. As research data have accumulated, however, it has become clear that the association between personality and illness is much more complex than first believed. Current research examines the impact on health of psychological constructs such as motivation, self-mastery, and self-confidence, as well as the impact of alcohol and substance abuse. Related factors under study include socioeconomic status, gender, and cognitive status.

Since the early 1950s, one major focus of psychosomatic research has been the relationship between the ‘‘Type A’’ personality and cardiovascular disease. Two cardiologists originally described a cluster of characteristics that many of their patients shared. People with Type A personalities were described as highly competitive and achievement oriented. They are also typically in a hurry and impatient; in addition, they are hostile in social interactions.

Major longitudinal studies in the 1960s and 1970s convincingly supported the notion that the Type A personality was a major risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease. In 1981, a panel organized by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) concluded that Type A behavior was a risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD). Since that time, however, several large, well-conducted studies (including the long-term follow-up to the original study which found a Type A–heart disease link) have found no association between Type A behavior and heart disease.

Researchers have proposed several possible explanations for the Type A turnabout. These include that (1) the original findings were just a fluke; (2) the assessment of Type A may have changed over time; (3) society may have changed, making the Type A distinction anachronistic; (4) coronary heart disease population distribution has changed (changing patterns of smoking, diet, and physical activity may interact with Type A behavior in unclear ways); or (5) some aspects of Type A behavior are risk factors, but others are not. Many studies have examined this latter possibility.

In one comprehensive meta-analysis examining the effects of psychological and behavioral variables on coronary heart disease, only the anger and hostility components of Type A were found to be significant CHD risk factors. Overall, Type A was unrelated to future disease status. Other studies, using both the Type A Structured Interview and the Cook-Medley Hostility (Ho) Scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Interview (MMPI), have found that ‘‘cynical hostility’’ is predictive of future coronary disease morbidity and mortality. People who are cynically hostile tend to expect the worst of others and dwell on people’s negative characteristics. This personality characteristic, unlike overall Type A behavior, does seem to predict future heart disease.

When considering the Type A and CHD research, it is important to note that the majority of research has been conducted with male subjects. Relatively little attention has been paid to CHD risk factors in women, despite the fact that CHD is the leading cause of death among women, killing more women than men each year. Only recently have researchers begun to examine the personality risk factors for women.

The relationship between hostility and diseases other than CHD has also been examined. A number of studies, for example, have found a link between hostility and all-cause mortality. Only one study, however, has controlled for CHD deaths in the analysis. In that study, MMPI Hostility scores correlated with 20-year, all-cause mortality rates, even when CHD-related mortality was factored out. To date, no studies have linked hostility to other major health outcomes, such as cancer.

Besides hostility, many other personal factors have been examined for their relationship to health. Notably, clinical and nonclinical depression have been related to poor health outcomes among certain disease groups. In one study of CHD and depression, clinical depression assessed in recently hospitalized post-myocardial infarction (MI; or heart attack) patients was associated with a 500% greater likelihood of 6-month mortality. In another study, 4000 hypertensive individuals were followed for 4.5 years. In this group, change in depression level (although not absolute level) predicted future cardiac events like infarctions and surgeries.

Other studies have shown that having an optimistic, rather than pessimistic, attitude may have important health consequences. Similarly, a negatively fatalistic outlook on life and health may be a prognostic indicator of poor future health status. In one 50-month study of 74 male patients with AIDS, increased survival time was significantly associated with low levels of fatalism, which was called ‘‘realistic acceptance.’’ Patients who had low scores on a measure of realistic acceptance had median survival times 9 months longer than patients with high levels. When potential confounds were controlled for, such as initial health status and ongoing health behaviors, the effect remained significant.

Similar findings have been obtained with other disease groups. Researchers often use all or part of the Life Orientation Test (LOT) as a measure of optimism and pessimism. In one study, a pessimistic attitude (as measured by LOT) was a significant mortality risk factor for young adults with recurrent cancer. Another study found that high LOT pessimism was associated with greater risk of MI during coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Another area of inquiry regarding personal factors and health involves recovery and adaptation after surgery. Researchers assessed a number of psychosocial variables in a population of 42 leukemia patients about to receive allogeneic bone marrow transplants. (Allogeneic transplants involve bone marrow from donors other than themselves or identical twins.) Participants who had an attitude toward cancer characterized by ‘‘anxious preoccupation’’ had increased mortality compared to nonanxious participants.

Finally, socioeconomic status (SES) has emerged as an important determinant of health status. Several studies have shown a clear gradient between SES and a variety of different indicators of health status. Furthermore, the association is continuous. For example, there are differences in health status between moderately poor people and those who are very poor. On the other end of the spectrum, it appears that there are differences between the very rich and those who are moderately well off. These differences are observed in nearly all cultures, including those with universal access to health care. Thus, health care alone does not seem to explain the association between SES and health status.

III. Examples of Behavioral Medicine in Clinical Practice

A. Treatment of Heart Disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), which includes coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (strokes), and peripheral artery disease, is the single most common cause of death in the United States. Caused by atherosclerosis, the buildup of fatty plaques along the inner walls of arteries, CVD causes significant disability and is a large source of health care costs. Behavioral medicine specialists have developed a number of interventions to prevent and treat CVD.

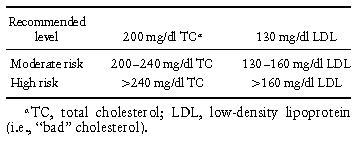

One risk factor for CVD is high blood cholesterol, or hypercholesterolemia. The diagnostic criteria for hypercholesterolemia are presented in Table I. The most prominent intervention effort aimed at treating hypercholesterolemia, initiated by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, is known as the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP).

Table I. National Cholesterol Education Program Guidelines for the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia

If atherosclerotic buildup increases, the arteries narrow and restrict blood flow. The formation of a clot can completely stop blood flow, causing an MI or cerebral vascular accident (CVA; or stroke). Atherosclerosis is a life-long process, partially controlled by inherited genetic factors such as metabolism. Although humans have no influence over their genes, our physiological factors affecting atherosclerosis include blood cholesterol, blood pressure, and obesity. These physiological factors and CVD risk are partially influenced by modifiable behaviors, for example, physical activity, diet, and tobacco use. Behavioral medicine practitioners are actively involved in developing effective interventions in these areas, at both the patient and caregiver level.

Regular physical activity may reduce blood pressure by reducing obesity, increasing aerobic fitness, and reducing the blood levels of certain stress-related chemicals such as adrenalin. In individuals who already have hypertension, exercise significantly reduced resting blood pressure in most studies. Other studies have examined the effect of activity interventions on individuals who do not yet have hypertension, but who are at high risk for developing it (e.g., people with ‘‘high normal’’ blood pressure). One such study found that increased physical activity was one factor reducing the risk of future hypertension in this population. Many other studies have found cardiovascular benefits from dietary and smoking interventions.

The benefits from these interventions, although significant, are limited. Atherosclerosis has traditionally been viewed as a unidirectional process. Therefore, behavioral and medical interventions have been aimed at slowing, rather than reversing the sclerotic process. Recently, however, the Lifestyle Heart Trial attempted to reverse atherosclerosis through behavior change. This trial was notable for its comprehensiveness. Patients with severe heart disease were randomly assigned to either a standard-treatment control group or a radical lifestyle change intervention. In the intervention group, participants were introduced to the program through a weekend retreat with their spouses. Then, participants attended 4-hour, biweekly group meetings. They were placed on an extremely low-fat vegetarian diet (fat was limited to 10% of calories, compared with a national average of about 40%). Caffeine use was eliminated, and alcohol was limited to two drinks per day. The group sessions included relaxation and yoga exercises; participants were expected to practice relaxation and meditation for 1 hour each day. Sessions also included exercise and smoking cessation instruction for participants who smoked.

The results of this intensive behavior change program were striking. Participants reduced their fat intake from 31% to 7% of total calories. They increased daily exercise from 11 minutes to 38 minutes per day. They increased their relaxation and meditation time from an average of 5 minutes per day to 82 minutes per day. As a result, participants’ total cholesterol levels dropped markedly, often to below150mg/dl. Blood pressure also fell. They lost, on average, 22 pounds over the 1-year course of the study. Angina (chest pain) dropped by 91% in the experimental group, whereas it increased by 165% in the control group. Impressively, participants in the experimental group were almost twice as likely as control group members to show actual reductions in arterial blockage.

This study demonstrated that a behavioral intervention that includes daily exercise and relaxation, along with an extremely low-fat diet, can have an impressive impact on the clinical picture of individuals with severe heart disease. Related research focuses on the impact of behavioral interventions on individuals who do not yet have heart disease, but who may develop it in the future.

B. Adaptation to Cancer

Cancer is universally feared. According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), cancer is an umbrella term for a group of diseases ‘‘characterized by uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells.’’ Not counting some highly prevalent, rarely fatal forms of skin cancer, the most common cancers are (in order of prevalence) prostate, lung, colon /rectal, and bladder (for men); and breast, colon /rectal, lung, and uterus (for women). For both men and women, lung cancer causes the most deaths. Although it kills far fewer people than CVD, cancer is perceived as more dangerous, destructive, and deadly. In reality, the survival rate for cancer has been climbing steadily throughout this century. Taking a normal life expectancy into consideration, the ACS estimates that 50% of all people diagnosed with cancer will live at least 5 years. Nevertheless, cancer remains the second-leading cause of death and is associated with significant pain and disability.

Because behavioral factors have been implicated in the etiology of many cancers (e.g., smoking, eating a low-fiber diet, sunlight exposure), behavioral scientists have developed a large number of programs designed to help people reduce their cancer risk. In addition, behaviorists have focused on what happens to an individual after a diagnosis of cancer is made. Partly because there are so many types of cancers, the experience of cancer is highly variable. Nevertheless, there are commonalities. Most cancer treatments, such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, are extremely unpleasant. Surgery often requires a great amount of recuperation, sometimes causes new physical problems, and may cause substantial disfigurement. Radiation and chemotherapy often cause significant side effects, including hair loss, sterility, even nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and diarrhea. Anticipatory anxiety, classically conditioned by these treatments, may increase the severity of many of these symptoms. In the long term, cancer patients face problems with physical, psychological, and sexual functioning, as well as family and work difficulties. Many studies have demonstrated that cancer patients exhibit increased rates of depression, and some have demonstrated increased rates of anxiety. Behaviorists working in treatment settings have attempted to help individuals with cancer cope as well as possible with these difficulties.

Health researchers have found that cancer may result in self-concept problems. In addition, one study identified four major sources of stress experienced by people with cancer: (1) loss of meaning, (2) concerns about the physical illness, (3) concerns about medical treatment, and (4) social isolation. Social isolation and reduced social activity have been observed in both children and adults with cancer. Behavioral science practitioners are developing interventions to ameliorate the psychosocial effects of cancer.

Interesting and controversial intervention studies have examined the effect of positive attitude and social support in reducing the physical effects of cancer. According to some psychoneuroimmunology studies, depressed mood may reduce immune functioning. ‘‘Wellness communities,’’ startled by Harold Benjamin in Santa Monica, California, promote the idea that depression weakens immune response. They suggest that a positive attitude may likewise enhance it. Stronger immunity, it is argued, will lead to reduced physical manifestations of the disease.

The most well-known study of social support and cancer was undertaken with a group of 86 women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. (Metastatic means the disease has spread beyond the original organ or tissue site.) The women were randomly assigned to either a standard treatment control group or a group that included weekly support groups. The support groups were led by psychiatrists or social workers who were breast cancer survivors themselves. Women in the support group became highly involved in helping the other participants cope with their cancer symptoms, treatment, and difficulties.

Women assigned to the support groups survived an average of 36.6 months, while those in the control group survived an average of only 18.9 months. Support group members also experienced less anxiety, depression, and pain. This study’s impressive results have sparked further research into the role of social support and immune functioning, as well as the role of psychotherapy in reducing the psychosocial difficulties of the cancer experience. The study is now being replicated with a larger group of women.

Another often-cited cancer intervention study examined the effects of a 6-week intervention on patients diagnosed with a deadly form of skin cancer known as malignant melanoma. The intervention included weekly 90-minute sessions focusing on relevant education, problem-solving skills, stress management, and psychological support. Outcome data indicated both short-term and long-term effects of the intervention versus the control group. At short-term (6-week and 6-month) assessments, immune markers were significantly better in the intervention group than in the controls. When studied 6 years later, the intervention group participants had lower mortality rates and fewer recurrences than did participants in the control group.

C. Functioning in Lung Disease

Another example of behavioral medicine practice comes from studies of rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is a common ailment among smokers. It is currently the fourth leading cause of death in the United States. Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and chronic asthma are the three diseases most commonly associated with COPD. The common denominator of these disorders is expiratory flow obstruction (difficulty exhaling air) caused by airway narrowing, although the cause of airflow obstruction is different in each. Exposure to cigarette smoke is the primary risk factor for each of these illnesses. There is no cure for COPD.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has a profound effect on functioning and everyday life. Current estimates suggest that COPD affects nearly 11% of the adult population, and that the incidence is increasing, especially among women, reflecting the increase in tobacco use among women in the latter part of this century. Medicines such as bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and antibiotic therapy help symptoms, and long-term oxygen therapy has been shown to be beneficial in patients with severe hypoxemia. However, it is widely recognized that these measures cannot cure COPD. Much of the effort in the management of this condition must be directed toward preventive treatment strategies aimed at improving symptoms, patient functioning, and quality of life.

In one study, 119 COPD patients were randomly assigned to either comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation or an education control group. Pulmonary rehabilitation consisted of 12 4-hour sessions distributed over an 8-week period. The content of the sessions was education, physical and respiratory care, psychosocial support, and supervised exercise. The education control group attended four 2-hour sessions that were scheduled twice per month, but did not include any individual instruction or exercise training. Topics included medical aspects of COPD, pharmacy use, and breathing techniques. In addition, subjects were interviewed about smoking, life events, and social support. Lectures covered pulmonary medicine, pharmacology, respiratory therapy, and nutrition. Outcome measures included lung function, exercise tolerance (maximum and endurance), perceived breathlessness, perceived fatigue, self-efficacy for walking, depression, and overall health-related quality of life.

In comparison to the educational control group, rehabilitation patients demonstrated a significant increase in exercise endurance (82% vs. 11%), maximal exercise workload (32% vs. 14%), and peak VO2, a measure of cardiovascular fitness (8% vs. 2%). These changes in exercise performance were associated with significant improvement in symptoms of perceived breathlessness and muscle fatigue during exercise.

Traditional models of medical care are challenged by the growing number of older adults with chronic, progressively worsening illnesses such as COPD. Cognitive–behavioral interventions may help patients adapt to loss of function and, when successfully used in a comprehensive rehabilitation program that includes training in energy conservation and the use of assistive devices, may even help to increase function. As a result, behavioral interventions can improve quality of life for patients with chronic pulmonary disease.

As in our discussion of behavioral medicine research, this section on the practice of behavioral medicine has highlighted some areas of active interest. Behavioral medicine practitioners have developed successful interventions in many other areas, such as diet and physical activity, tobacco use, and pain management.

IV. Behavioral Medicine in Public Health

In addition to clinical contributions, behavioral medicine often takes a public health perspective. The public health perspective differs from the clinical viewpoint because of its focus on the community rather than on the individual. In public health, the emphasis is on improving the average health of an entire population rather than on the health of specific patients. Three areas where behavioral medicine intersects with public health are epidemiology, preventive medicine, and health policy.

A. Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study of the determinants and distribution of disease. Epidemiologists measure disease and then attempt to relate the development of diseases to characteristics of people and the environments in which they live. The word epidemiology is derived from Greek. The Greek word epi translates to ‘‘among,’’ and the Greek word demos translates to ‘‘people.’’ The stemology means ‘‘the study of.’’ Epidemiology, then, is the study of what happens among people. For as long as there has been recorded history, people have been interested in what causes disease. It has been obvious, for example, that diseases are not equally distributed within populations of people. Some people are much more at risk for certain problems than are others.

Traditionally, most epidemiologists studied infectious diseases. For example, people who live in close contact are most likely to get similar illnesses or to be ‘‘infected’’ by one another. Ancient doctors also recognized that people who became ill from certain diseases, and who subsequently recovered, seldom got the same disease again. Thus, the notions of communicability of diseases and of immunity were known many years before specific microorganisms and antibodies were understood. Epidemiologic history was made by Sir John Snow who studied cholera in London in the mid-nineteenth century. Cholera is a horrible disease that causes severe diarrhea and eventually kills its victims through dehydration. Snow systematically studied those who developed cholera and those who did not. His detective-like investigation demonstrated that those who obtained their drinking water from a particular source (a well in London) were more likely to develop cholera. Thus, he was able to link a specific environmental factor to the development of the disease, and actions based on this knowledge saved many lives. This occurred many years before the specific organism that causes cholera was identified.

It is common to think of epidemics as major changes in infectious disease rates. For example, we are experiencing a serious epidemic of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).Yet there are other epidemics that are less dramatic. For instance, we are also experiencing a major epidemic of coronary heart disease in the United States. In 1900, heart disease accounted for about 15% of all deaths, whereas infectious diseases, such as influenza and tuberculosis, accounted for nearly one quarter of all deaths. In the 1990s, cardiovascular (heart and circulatory system) diseases caused nearly half of all deaths. The days when infectious diseases were the major killers in the industrialized world appear to be over. AIDS, although rapidly increasing in incidence, still accounts for only about 1% of all deaths. Today, the major challenge is from chronic illnesses. The leading causes of death include heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive lung disease, and diabetes. Each of these may be associated with a long period of disability. In addition, personal habits and health behaviors are associated with both the development and the maintenance of these conditions.

It is important to consider the relative importance of different risk factors and different causes of death. Heart disease is clearly the leading cause of death in the United States, with an estimated 733,867 deaths in 1993. Stroke accounted for another 145,551 deaths. Cancer accounted for 496,152 deaths in 1993. Diabetes mellitus accounted for more than 46,833 deaths, and COPD was responsible for 84,344 deaths.

B. Behavioral Epidemiology

We use behavioral epidemiology to describe the study of individual behaviors and habits in relation to health outcomes. Wise observers have been aware of the relationship between lifestyle and health for many centuries. This is evidenced by the following statement from Hippocrates in approximately 400 BC:

Whoever wishes to investigate medicine properly, should proceed thus: . . . the mode in which the inhabitants live, and what are their pursuits, whether they are fond of drinking and eating to excess, and given to indolence, and are fond of exercise and labor, and not given to excess eating and drinking.

There were approximately 2,269,000 deaths in the United States in 1993 (latest CDC report). Deaths are accounted for according to major and underlying cause. The traditional biomedical model has emphasized disease-specific causes of death, and pathways to prevention have typically considered risk factors for particular diseases. For example, cigarette smoking is associated with deaths from cancer of the lung. Thus, efforts to reduce lung cancer concentrate on smoking cessation. However, most of the major causes of death are associated with a variety of different risk factors. Furthermore, many risk factors are associated with death from a variety of different causes. For example, tobacco use causes not only lung cancer, but a wide variety of other cancers, as well as heart disease, stroke, and birth complications.

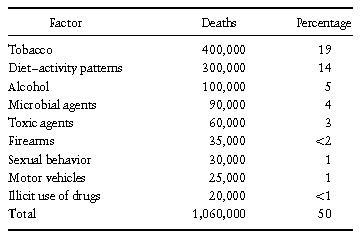

Major nongenetic contributors to mortality were examined in an important analysis in 1993 by McGinnis and Foege. They identified several behaviors that account for large numbers of deaths. A summary of the estimates for actual causes of death in the United States is presented in Table II. Tobacco use is associated with more than 400,000 deaths each year, and diet and activity patterns account for an additional 300,000. These dwarf the number of deaths associated with problems that the public is generally concerned about, such as illicit drug use. The McGinnis and Foege analysis challenged society to think differently about health indicators in the United States. Only a small fraction of the trillion dollars the United States spends annually on health care is devoted to the control of the major factors that cause premature mortality in the United States. Estimates suggest that less than 5% of the total annual health care budget is devoted to prevention efforts. Because behaviors are the major causes of death and disability, it is clear that behavioral scientists have an important role to play in many areas of public health and clinical medicine.

To underscore the role of behaviors in premature mortality, we consider two examples; tobacco use and physical activity.

Table II. Actual Causes of Death—United States, 1990

Source: McGinnin & Feoge, JAMA, 270, 2207–2212, 1993.

1. Tobacco

Cigarette smoking remains the greatest single cause of preventable deaths in contemporary society. The health consequences of tobacco use have been documented in thousands of studies. Although cigarette smoking has declined in the United States and in the United Kingdom in recent years, the worldwide trend is toward increased use of tobacco products. In addition, although adult smoking has declined markedly, smoking among teens is on the rise. It is projected that worldwide there will be 10 million tobacco-related deaths per year by the year 2010. Current estimates suggest that tobacco use in the United States is responsible for 434,000 deaths each year. These include 37,000 deaths from cardiovascular disease resulting from exposure to tobacco smoke in the environment (so-called second-hand smoke). Furthermore, smoking is responsible for poor pregnancy outcomes. Between 17 and 26% of low birth weight deliveries are associated with maternal tobacco use and 5 to 6% of prenatal deaths can be attributed to maternal tobacco use. McGinnis and Foege suggest that about 25,000 deaths in the United States can be attributed to motor vehicle accidents, and about 20,000 deaths can be attributed to illicit drug use. In contrast, deaths associated with tobacco use account for more than 20 times the number associated with drug use, 16 times the number associated with auto crashes, and 15 times the number of homicides.

Financial barriers to treatment for nicotine addiction have been formidable—for the patient and for the provider. Most health insurance plans in the United States, public and private, exclude coverage for tobacco addiction treatments. This helps to explain why only 10 to 15% of the U.S. smokers who have tried to quit have ever received any formal treatment for nicotine addiction, and why low-income and disadvantaged Americans have been least likely to get help. Lack of reimbursement also helps to explain why, even today, only 50% of the nation’s smokers report ever having been advised by their doctors to quit smoking.

2. Physical Activity

Research shows that people who are physically active live significantly longer than those who are sedentary. These studies have documented a relationship between physical activity and all-cause mortality, CHD mortality, mortality from diabetes mellitus, and mortality associated with COPD and other lung diseases. In addition to living longer, those who engage in regular physical activity may be better able to perform activities of daily living and enjoy many aspects of life. Furthermore, those who exercise regularly have better insulin sensitivity and less abdominal obesity. Regular exercise has also been shown to improve psychological well-being for those with mood disorders. Successful programs have been developed to promote exercise for the general population. Also, specific interventions have been developed for those diagnosed with particular diseases.

Despite the benefits of exercise, few people will start an exercise program, and many of those who start do not continue to exercise. Some predictors of failure to exercise regularly include being overweight, poor, female, and a smoker. However, the most commonly reported barriers to exercise are lack of time and inaccessibility of facilities.

Studies show that exercise patterns change as people age. Children are active, but physical activity declines substantially by the late teens and early twenties. It appears that Americans are shifting toward less vigorous activity patterns, with walking becoming the most common form of exercise. Physical inactivity may be increasing as Americans spend more time watching television or working with computers.

Methods to enhance exercise include environmental manipulation, behavior modification, cognitive– behavior modification, and educational approaches. The behavior modification interventions use principles of learning to increase physical activity. These interventions typically control the contingencies associated with physical activity and reinforce active behaviors. Cognitive–behavior modification interventions are similar to behavior modification approaches. However, they also modify self-defeating thoughts that may turn people off to exercise. Educational interventions attempt to increase activity by teaching people about the benefits of being physically active. Statistical analysis that average results across studies (called meta-analyses) tend to show that interventions based on behavior modification principles produce the largest benefits. Interventions based on health education or health risk appraisal approaches tend not to produce consistent benefits. Cognitive–behavior modification interventions also have produced less consistent results than behavior modification approaches. Interventions that include incentives and social support increase exercise in the short term. Many of the studies show that people have difficulty maintaining their exercise programs over the course of time.

Exercise programs are now common for patients with heart, lung, and blood diseases. Cardiac rehabilitation has become a widely chosen and accepted treatment option for patients with established coronary artery disease. As recently as 1970, post-MI patients were typically hospitalized for 1 month and advised to take total bed rest. Today, the average MI patient is hospitalized for 5 to 7 days and lengths of stay continue to decline. Furthermore, the majority of patients are advised to resume physical activity relatively promptly following an MI. Exercise is the core component of the rehabilitation process. Meta-analyses of controlled studies in rehabilitation have demonstrated 20 to 25% reductions in mortality. Newer studies are beginning to demonstrate improvements in quality of life as well as life duration.

Studies of patients with COPD have also demonstrated benefits associated with exercise. Although studies tend not to show changes in lung functioning, some studies have documented improvements in exercise capacity, performance of activities in daily living, and mood. Studies have not demonstrated improvements in life expectancy.

Although there are few intervention studies, evidence suggests that physical activity also predicts survival for patients with cystic fibrosis. In one study, 83% of patients who had the highest levels of aerobic fitness survived for 8 years in comparison to 58% and 28% of patients in the middle and lowest thirds, respectively, of the distribution for aerobic fitness.

C. Prevention Sciences

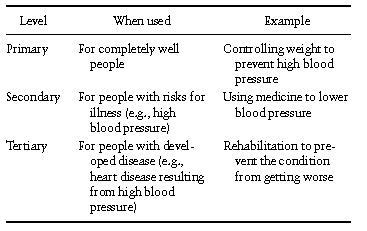

Behavioral medicine has a strong commitment to disease prevention. Prevention can be divided into primary and secondary. Primary prevention is the prevention of a problem before it develops. Thus, the primary prevention of heart disease starts with people who have no symptoms or characteristics of the disease and there is intervention to prevent these diseases from becoming established. In secondary prevention, we begin with a population at risk and develop efforts to prevent the condition from becoming worse. Tertiary prevention deals with the treatment of established conditions and is the main focus of clinical medicine. Table III uses the example of high blood pressure to illustrate these three approaches to prevention.

Table III. Three Levels of Prevention

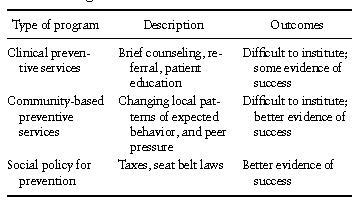

Prevention has different meanings for different people. Partners for Prevention, a nonprofit organization, emphasizes that there are at least three different components of prevention. These include clinical preventive services, community-based preventive services, and social policies for prevention. Clinical preventive services typically involve medical treatments such as immunization and screening tests. Clinical services may also include counseling and behavioral interventions. Community-based preventive services include public programs to ensure safe air, water, or food supplies, as well as behavioral interventions to change local patterns of diet, exercise, or smoking. Social policies for prevention might involve regulation of environmental exposures or exposure to hazardous materials at the work place. These social approaches also include taxes on alcohol and cigarettes and physical changes to ensure better traffic safety. Examples of these three types of prevention programs are given in Table IV.

Table IV. Examples of Three Types of Prevention Programs

D. Health Care Policy

The American Health Care System is perhaps the most complex in the world. The United States represents only about 5% of the world’s population, but accounts for about 40% of all health care expenditures worldwide. It is difficult to describe U.S. health care as a ‘‘system.’’ Rather, U.S. health care is a patchwork of overlapping systems of public and private insurance, with as many as 40 million persons uninsured for their medical expenses.

It is commonly argued that traditional fee-for-service medicine provides few incentives to offer behavioral medicine and preventive services. Indeed, the higher the rates of medical service utilization the greater the profit. One attractive feature of the current move toward managed care is that there are substantial incentives to prevent illness and to reduce health care utilization. From a public health perspective, managed care organizations have responsibility for a defined population. If they can keep this population healthy by investing in prevention, they may ultimately profit by having reduced costs and higher consumer satisfaction.

There are several reasons why the potential for behavioral and disease prevention has often been overlooked by public-policy makers. Preventive services rarely make headlines or gain the same attention as high technology medical interventions. For example, transplantation of a diseased heart attracts the media and brings adulation from family and friends. A patient who survives such transplantation is thought to have benefited from the miracles of modern medical science and the surgeons are handsomely rewarded. When an illness is prevented, no one is aware that a problem has been avoided. There are no headlines because there is no news, and there are no fees for the experts who helped avoid a catastrophe. The average effect of prevention for any one person may be small, yet preventive services have the potential for a huge impact. As noted in Table II, an estimated 400,000 Americans die prematurely each year as a result of tobacco use. As many as 100,000 people die prematurely each year as a result of unnecessary injuries or illnesses related to alcohol abuse. Substantial numbers of cancer and heart disease deaths may be prevented or at least delayed through lifestyle modification.

Most of the 3 to 5% of the health care dollar used for prevention is devoted to clinical preventive services offered by physicians. For example, the great majority of expenditures on prevention relate to screening for diseases such as breast cancer, cervical cancer, and prostate cancer. The purpose of the prevention service is to detect a disease that already exists and medically treat it so that progression is retarded. The screening tests have become profitable for the providers who offer them and there is growing concern about abuses or profiteering by those who administer tests to people who do not need them. Many behavioral medicine professionals advocate a greater emphasis on prevention programs to change behaviors that are causing the most deaths.

V. Summary

Behavioral medicine is a strong and growing field. It draws its strength from its comprehensive approach and interdisciplinary nature. Rather than retreating to small niches, as is so common in science today, behavioral medicine researchers and clinicians must obtain knowledge from a wide variety of disciplines relevant to their field. A behavioral medicine researcher studying CHD must know about basic cardiac functioning, personality research, and many other seemingly unrelated pieces of information. By the nature of this comprehensive approach, the behavioral medicine specialist, whether she is a nurse practitioner, psychologist, or physician, brings a much needed perspective to the science of health and behavior.

Bibliography:

- Kaplan, R. M., Orleans, C. T., Perkins, K. A., & Pierce, J. P. (1995). Marshaling the evidence for greater regulation and control of tobacco products: A call for action. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 17, 3–14.

- Kaplan, R. M., Sallis, J. F., & Patterson, T. L. (1993). Health and human behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Matarazzo, J. D. (1980). Behavioral health and behavioral medicine: Frontiers for a new health psychology. American Psychologists, 35, 807–817.

- McGinnis, J. M., & Foege, W. H. (1993). Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 270, 2207–2212.

- Peto, R., Lopez, A. D., Boreham, J., Thun, M., & Heath, Jr., C. (1992). Mortality from tobacco in developed countries: Indirect estimation from national vital statistics. Lancet, 339(8804), 1268–1278.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.