This sample Community Psychology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Community Psychology is a branch of psychology that examines the ways individuals interact with other individuals, social groups, societal institutions, the larger culture, and the environment. The focus is on how individuals and communities can work together to provide a healthy and sustainable environment. Because of its applied focus, it is different from other areas of psychology in a number of ways, including areas of interest, research methods used, level of analysis employed, and the nature of the interventions that are developed. Community psychology is concerned with social institutions, social issues, and social problems. Research in community psychology explores such topics as poverty, substance abuse, school failure, homeless-ness, empowerment, diversity, delinquency, aggression, and violence.

Unlike many other branches of psychology, community psychology makes no pretense of being value-free. Community psychologists reflect on their personal values, bring their values to the forefront of their work, and acknowledge the effect their values have on what they do. Community psychologists understand that values can influence how we frame research questions. More important, values are an important determinant of human action.

The importance of values to community psychology researchers is that values not only guide actions but also are transsituational, having an effect across time and contexts. In recognizing the importance of values, community psychologists have been careful to be explicit about their own values. Some of the core values that guide community psychology are holistic models of health and wellness, social justice, self-determination, accountability, respect for diversity, basing action on empirical research, and support for community structures that encourage commitment, caring, and compassion.

Community psychology is closely tied to, albeit somewhat different from, several related disciplines. Community psychology shares sociology’s interest in the study of macro systems but also provides an interventionist orientation in promoting social change that contributes to a more equitable distribution of resources and social justice.

Like social work, community psychology is concerned with multiculturalism and social welfare, and, like clinical psychology, the results of planned interventions are designed to promote wellness. However, community psychology has a greater research orientation than social work, and is more likely than clinical psychology to promote treatment options that require societal change rather than individual change.

Community psychologists and public health practitioners both focus on prevention and intervention to solve social problems; however, community psychologists are more likely to appreciate the importance of mental health variables in a wide range of health issues.

Environmental psychology and community psychology both focus on improving the quality of people’s lives and both use interdisciplinary approaches to research and practice. However, community psychology is more concerned with the socially constructed environment than with the natural environment.

Both community psychology and social psychology examine the effects of social influence and situational factors on human behavior. However, community psychology places greater emphasis on the external world, while most social psychologists focus on individual interpretations of that world.

How Did Community Psychology Develop?

Community psychology emerged in the United States during the mid-20th century, although there were pioneer psychologists, such as William James and G. Stanley Hall, who promoted the use of social and behavioral sciences to enhance people’s well-being. The founding of the field came about as the result of powerful social forces, such as the great depression in the 1930s and World War II in the 1940s. These events served as a catalyst: forcing people to con-front poverty, racism, prolonged stress, and the treatment of minorities. Most people date the formal foundation of the field from the Swampscott Conference in 1963, where the term community psychology was first coined. At that conference, the role of the community psychologist was proposed as an alternative to the disease and treatment orientation of clinical psychologists. Many forces led to the development of community psychology, including social change movements such as the civil rights movement and feminism, optimism in finding solutions to social problems, a preventive perspective in addressing mental health issues, reforms in mental health care, and action research on policy issues.

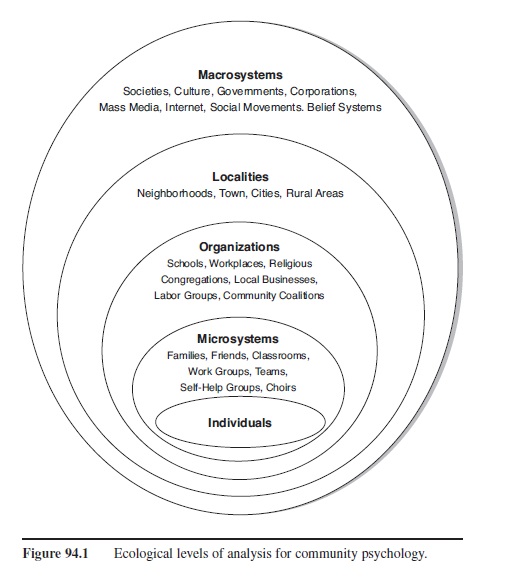

Since the beginning, there has been an ongoing debate about the relation between community psychology and clinical psychology. During the 1970s, the field of community psychology began to diverge from the field of community mental health to address a broader range of issues. This divergence came about as a result of a difference in perspective that reflected a number of issues. The first issue was a debate as to whether the field should address ways to improve the mental health of individuals or change the social conditions that affect individual’s mental health. A second issue concerned the focus of research and action and what is an appropriate level of analysis: individual, group, neighborhood, or society. Reflecting this broad perspective, Figure 94.1 illustrates the ecological levels of analysis used in community psychology. It includes proximal systems (those closest to the individual involving face-to-face contact) as well as distal systems (those that are less immediate to the individual but have broad, societal effects).

Figure 94.1 Ecological levels of analysis for community psychology.

Figure 94.1 Ecological levels of analysis for community psychology.

In the early development of community psychology, white males made most of the contributions to the field. During the 1970s, women and persons of color began to move the field to include an examination of the role of race and gender. By the 1980s, community psychology had become an international field. For example, in Latin America, community social psychology emerged, with a focus on social change. The issues of empowerment and liberation were added to the concerns being addressed and the process of collaborative, participatory research methods began to be employed.

The conservative sociopolitical climate of the 1980s led to an understanding of how social issues are defined in progressive and conservative times. M. Levine and A. Levine (1992) pointed out that in human services work there is a correlation between the social ethos of the times and the form of help offered. They proposed the following hypothesis: In progressive times, environmental explanations of social problems will be favored, which encourages intervention programs designed to change the community; in conservative times, individualistic explanations will be favored, which encourages intervention programs designed to change individuals. For community psychology, conservative times provide both opportunities and challenges. Fortunately, the two points of view have some shared beliefs, including skepticism about top-down programs, a preference for grassroots decision making, and the recognition that some community programs have long-term economic benefits that offset short-term costs.

After the Swampscott Conference, and in recognition of the growing importance of community psychology, the American Psychological Association created a Division of Community Psychology (27), which is now called the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA). Since the 1980s, the SCRA has promoted active participation of both practitioners and action-oriented researchers both in the United States and around the world. In their 2001 mission statement, they identify four broad principles that guide the work of community psychologists:

- Community research and action requires explicit attention to and respect for diversity among peoples and settings;

- Human competencies and problems are best understood by viewing people within their social, cultural, economic, geographic, and historical contexts;

- Community research and action is an active collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and community members that uses multiple methodologies;

- Change strategies are needed at multiple levels in order to foster settings that promote competence and well-being.

Theoretical Approaches To The Study Of Community Psychology

One of the most influential early theorists was Kurt Lewin (1935). Historians generally credit Lewin with coining the term “action research,” which he defined as research on the conditions and effects of social action, as well as research leading to social action. Action research involves a series of steps that begin with identifying an initial idea, followed by reconnaissance or fact finding that lays the groundwork for the planning stage. In action research, a sequential approach follows that includes taking the first action step (e.g., an intervention), evaluating the effects of that action, amending the plan based on the results, and taking the next action step. Action research also involves active collaboration between researchers and others who have a stake in the results of the research. For example, one early study examined why a gang of Italian Catholics had disturbed Jewish religious services. Lewin brought together workers who were Catholics, Jews, African Americans, and Protestants. Their first step was to put the gang members into the custody of local priests. Next they reached out to the local community to discuss improvements. Based on the discussion, Lewin decided that the problem was not one of anti-Semitism but of general hostility, based on several frustrations associated with community life. By addressing issues of housing, transportation, and recreation, members of different groups integrated, and within a year, conditions had improved greatly.

Ecological Psychology

Roger Barker’s (1968) contribution to community psychology was the development of ecological psychology, which views the relation between the individual and the environment as a two-way street, characterized by interdependence. Barker used the term behavior setting to describe naturally occurring social systems in which certain behaviors unfold, such as a soccer game. A particularly influential aspect of his theory examines staffing, which refers to the critical number of people needed to fill the necessary roles, in a given setting. A behavior setting is understaffed if the number of people is less than those needed to maintain a behavior—the maintenance minimum. Overstaffing occurs when the number of people involved exceeds the capacity of the behavior setting. An example of research based on staffing theory is the work of Wicker (1969), who found that members of small churches are more likely to be involved in more behavior settings within the church (e.g., committees, choir, religious education).

Social Climate

Rudolph Moos’s (1976) contribution to community psychology was the development of social climate scales, which allow researchers to assess what social settings mean to people, as a starting point for interventions. Social climate refers to the personality of a setting, which can be characterized according to three dimensions: personal development orientation, relationship orientation, and system maintenance/change orientation. His scales have been used in a variety of ways, one of which is to identify what outcomes are associated with different climates. For example, Moos found that climates in which the relationship orientation is high foster greater personal satisfaction, heightened self-esteem, and lower irritability. Another contribution of Moos was the concept of person-environment fit based on the distinction between real and ideal climates. Assessments that examine the discrepancy between real and ideal environments have important implications for interventions.

Ecological Analogy

James Kelley’s theoretical contribution was the use of ecological analogy to plan community interventions. He described four ecological principles that continue to influence the work of community psychologists. The first principle is interdependence—the actions of one part of an ecological system influence all of the other parts. For example, welfare reform that required most welfare recipients to find work increased the number of working poor who had greater needs for inexpensive transportation and child care. The second principle is adaptation—the ability of individuals to respond to the changing demands of their environment, its values, norms, priorities, and goals. For example, despite the fact that the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population is people over the age of 75, our society has not developed a clear understanding of either their needs or their potential contributions. The third principle in Kelley’s theory is the cycling of resources—making use of people’s talents and skills, community characteristics, and shared values that promote community identity and action. Kelley’s fourth principle is succession—the recognition that systems are not static but ever changing. For example, in the workplace two common mechanisms of succession are promotion and retirement.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model

The Bronfenbrenner model suggests that individuals exist in nested social systems. The person exists within a family that lives in a town, which is part of a country, and so on. Bronfenbrenner (1977) identified four main levels of social systems. They are the microsystem, which is the setting that includes the actual person, such as the family or workplace; the mesosystem, which consists of interactions between microsystems—for example, the relation between a family and the neighborhood school; and the exosystem, which is the formal and informal social structure that affects individuals. For example, mom’s workplace would be an exosystem for her children. The fourth level is the macrosystem, which is the overarching pattern of the society or culture. The macrosystem includes the legal, economic, political, and other social systems that influence the other systems. Bronfenbrenner’s theory has proved useful in helping us consider the many levels of analysis that are relevant to understanding human behavior.

Methods Of Community Research

As early as the Swampscott Conference, it was clear that traditional laboratory methods would not be sufficient for studying community psychology. In choosing appropriate research methods, community psychologists are guided by the following six principles: research reflects social values, is linked to action, includes collaboration between the researcher and participants, recognizes that research in the real world is complex, pays attention to the context of the research including the use of multiple levels of analysis, and finally, is culturally anchored, which means that the questions being asked are meaningful to the group or groups being studied.

Qualitative Methods

Participant observation, qualitative interviewing, focus groups, and case studies are all qualitative methods used by community psychologists. Most of these methods have the following common features: contextual meaning, which is the quest to understand the meaning of a phenomenon for those who experience it; a personal, mutual relationship between researcher and participant; sampling procedures that include close relationships; active listening and the use of open-ended questions; reflexivity, which requires researchers to be open about their personal agenda; and a data-collection process that promotes checking with participants and acknowledges multiple interpretations of the data.

Participant Observation

This approach provides the researcher with considerable insider knowledge and depth of experience in a community. This method allows the researcher to get to know the setting and its people thoroughly.

Qualitative Interviewing

This approach utilizes open-ended or minimally structured questions that allow flexibility and the chance to explore ideas or issues that the researcher did not anticipate in designing the study. This method has advantages over participant observation in that data collection is more standardized and can be recorded for subsequent reanalysis. In addition, the interviewer can develop an authentic relationship with the participants. One disadvantage is the time required of the participants, which can exclude participants in marginalized groups or demanding circumstances (see Campbell & Wasco, 2000).

Focus Groups

These provide the opportunity for the researcher to interview an entire group. This allows for the assessment of similarities and differences among members of the group and for participants to stimulate responses from one another. The responsibility of the researcher is to create an environment that encourages open discussion, using language that is comfortable to the participants and eliciting opinions that cover the full range of those held by the participants.

Case Studies

These are a good way to create grounded theory, which is theory that is based in preliminary data collection. Whereas the classic case study in clinical psychology is of one individual, case studies by community psychologists can include a group or an individual in relation to a group.

Quantitative Methods

Although there is a great diversity among quantitative methods, those used by community psychologists share the following common features. Researchers use quantitative methods to measure differences between variables and the strength of the relation among variables. In community psychology, this allows for numerical comparisons across behavioral contexts with the goal of understanding cause-and-effect relations. The advantage to the community psychologist is that these methods may identify social conditions that have predictable consequences. Another important feature of quantitative methods is that they allow for generalization beyond the individual or group being sampled to the population that the group represents. Finally, the quantitative approach has led to the development of standardized measures that provide reliable, valid predictions across studies.

Quantitative Description

This refers to a variety of methods, including surveys, structured interviews, and the use of social indicators (e.g., crime statistics). Although these methods are quantitative, they are not experimental because they do not require manipulation of an independent variable. These approaches have many applications, including the measurement of characteristics of community settings (e.g., frequency of emotional support given in a crisis recovery group), comparison of existing groups (e.g., sex differences in the perception of sexual harassment in the workplace), and associations among survey variables (e.g., correlation between town size and likelihood of helping a stranger).

Geographical Information Systems (GIS)

This technique allows researchers to investigate the relation between physical-spatial aspects of communities and their psychosocial qualities (Luke, 2005). For example, a study by Dillon, Burger, and Shortridge (2006) used GIS techniques to examine the interval of time it took for an ethnic group’s signature food (Tex-Mex) to make the transition from “exotic ethnic other” to “common ethnic American” in Omaha, Nebraska, as a way of studying assimilation and diffusion among immigrant groups.

Experimental Social Innovation and Dissemination (ESID)

This approach to community research was developed by Fairweather (1967) in an attempt to use traditional experimental designs to evaluate the effects of an intervention. In ESID, researchers conduct a longitudinal study in which the intervention is compared to a control or comparison condition. One form of this approach is the randomized field experiment, in which participants are randomly assigned to experimental or control groups. They are compared on a pretest for equivalence and, after undergoing the intervention, are compared on a posttest to detect change. A second form of this approach is the nonequivalent comparison group design. This is used when random assignment to condition is not practical. For example, a hospital could not randomly assign patients to innovative versus traditional treatment programs. In using this approach, researchers use an existing group for comparison processes. Thus, the recovery rates of patients who were treated by traditional means could be compared to those of patients being treated by new techniques. The last form of this approach is the interrupted time-series design. This involves repeated measurement of a single event over time. In an initial baseline period, the participant is measured on the variable of interest, after which the social innovation is introduced while measurement continues. Data collected during the baseline are compared to data collected during and after the implementation of an innovation.

All of these methods have different strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of what method to use depends on the nature of the question being asked, the participants being studied, and the amount of control the researcher has regarding the process and the setting. Researchers can integrate quantitative and qualitative methods into a single study or several related studies in order to take advantage of both approaches and to minimize the weaknesses of any given approach.

Promoting Social Change

Community psychology’s social agenda has proved attractive to many, and remains an important aspect of the field. What do we mean by social change? Community psychologists distinguish between first-order change and second-order change (Watzlawick, Weakland, & Fisch, 1974). First-order change involves increasing the amount of current resources in solving the problem—for example, additional shipments of food to people in drought-stricken areas. Second-order change focuses on changing the systems that have contributed to the problem. When community psychologists talk about social change, they are usually talking about second-order change. In her excellent textbook on community psychology, Rudkin (2003) describes factors that promote second-order social change, which is the kind of change that requires breaking the rules or devising new rules. Among the factors that promote social change, she lists creative thinking, positive attitudes toward social equality, tolerance for disruptions in current practices, a willingness to change reward structures, appreciation for marginalized people, a sense of shared identity with others, and a strong value base.

How do these factors emerge? One contribution is exposure to alternative points of view, especially through cultural exchange whereby individuals are exposed to differing worldviews as well as alternative practices. Although exposure to people different from ourselves can broaden our perspective, individuals differ in their willingness to learn from such experiences.

To promote social change, community psychologists have several different strategies that have proved to be effective (see Dalton, Elias, & Wandersman, 2007). The first of these is consciousness raising. This process involves making people aware of social conditions and energizing their involvement in promoting solutions. Forums for consciousness raising include books, media productions, town meetings, and online chat rooms.

Social action involves power and conflict. It is a process of organization at the grassroots level to empower disadvantaged groups in confronting the power of those with considerably more financial and social resources. The U.S. civil rights movement is an example of social action. In Saul Alinsky’s (1971) Rules for Radicals, he described the principles required for effective social action: (a) identify the capacity/strengths of your group and their potential to act in concert, (b) identify the capacity of the opposing group or community institution, and (c) identify a situation that dramatizes the need for change.

Unlike social action, Community Development does not include conflict. It is the process of strengthening the relationship among members of a community during which the members identify problems as well as the resources and strategies for addressing those problems. In using this approach, it is typical to bring together representatives of all of the stakeholders in a locality, such as civic organizations, religious groups, schools, and businesses. According to Perkins, Crim, Silberman, and Brown (2004), community development efforts often target one or more of four domains: economic development (e.g., new businesses), political development (e.g., fostering access of community representatives to political decision makers), improving the social environment (e.g., promoting youth development programs), and improving the physical environment (e.g., better housing). A recent example of community development is the Valley Interfaith coalition of church and school groups in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. This coalition is involved in securing better services for Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants who bought housing lots but were never provided with the promised sewers, water, electricity, or paved roads (see Putnam & Feldstein, 2003).

Community coalition involves bringing together a broad representation of individuals within a location to address a community program. The coalitions often involve community agencies, schools, government, religious groups, businesses, the media, and so on. Coalitions address an agreed-upon mission by implementing action plans that may involve members of the coalition or affiliated organizations. The healthy communities movement (Wolff, 2004) often uses community coalitions to address health issues requiring wide-ranging solutions, such as respiratory diseases related to air quality.

Organizational consultation is a change process in which professional consultants provide communities with strategies for change. These strategies may address policy issues, role definition, decision making, communication processes, or conflict resolution. For example, the Michigan Roundtable for Diversity & Inclusion provides organizations with consulting services to help plan training programs that address diversity issues in schools, businesses, and other community organizations.

Alternative settings refers to the creation of community agencies in response to dissatisfaction with mainstream services. Some examples of alternative settings are women’s shelters, rape crisis centers, charter schools, and street health clinics. Mutual self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, have flourished amidst widespread dissatisfaction with the effectiveness of traditional treatment options. Typically, alternative settings rely on individuals with common experiences working together to address issues. This can promote a sense of community, social justice, respect for diversity, and self-determination.

The seventh and final approach to social change is Policy Research and Advocacy. This approach seeks to influence decision makers by providing research that addresses an area for which the decision maker is responsible. Policy research and advocacy may target government officials, including members of the legislative, judicial, or executive branches, or key decision makers in the private sector. A classic case that involved this approach was the Supreme Court desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education, which relied heavily on social science research in defining and examining the effects of inequity in education (see Clark, 1955).

Addressing Human Diversity

What do we mean when we say human diversity? What makes us unique? Is it our nationality, age, or sex, and of these, which is the most important in determining our sense of identity? There are many forms of diversity that are of interest to community psychologists, including culture, race, ethnicity, sex, social class, age, ability/disability, sexual orientation, and religious affiliation.

Cultural Diversity

The area of diversity is becoming more and more important in our multicultural society. In addition to the obvious cultural differences that exist between peoples, such as language, dress, and traditions, there are also significant variations in the way people in different societies form their identity, organize themselves, and interact with their environment. These variations are based on cultural syndromes, which are patterns of beliefs, attitude norms, and values that are organized around a unifying theme within a society. One of the most studied syndromes is individualism/collectivism. According to Triandis (1972), individualism/collectivism is the degree to which a culture encourages and facilitates the needs, desires, and values of the individual over those of the group. Individualists see themselves as separate and unique, whereas collectivists see themselves as fundamentally connected with others. In individualistic cultures, personal needs and goals are given more weight, whereas in collectivist cultures, individual needs are sacrificed for the good of the group. A second cultural syndrome is power distance (Hofstede, 1980). This dimension refers to the degree of power inequality between more and less powerful individuals, which varies considerably across cultures. Another cultural syndrome identified by Hofstede is uncertainty avoidance, which is the degree to which cultures develop mechanisms to reduce uncertainty and ambiguity. One final syndrome of importance to community psychologists is masculinity, which is the extent to which cultures foster traditional gender differences. In recognizing the nature of the local culture, community psychologists can better tailor intervention efforts to meet cultural expectations. It is not possible to understand many communities only in cultural terms. The next section explores how issues of social justice, especially oppression and liberation, are also important in understanding the challenges of diversity.

From Oppression To Liberation

Oppression refers to a situation in which a dominant group unjustly withholds power and resources from another group (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2005). For example, racism in America occurs because a privileged group of white persons have access to resources, opportunities, and power not available to ethnic minorities. Other forms of oppression include sexism (discrimination directed at women), classism (discrimination toward those with low incomes), ableism (discrimination toward those with physical or mental disabilities), and heterosexism (discrimination toward homosexuals). Sadly, individuals who belong to a nonprivileged class have been known to develop a sense of inferiority, referred to as internalized oppression. Sometimes, the source of oppression is not in members of the privileged class, but is rooted in an oppressive system with historical roots. For example, sexism is due, in part, to patriarchy, which promotes emotional restriction and competitiveness, and can actually harm men as well as women.

Liberation is the process of acquiring full human rights for all members of a community and remaking the community to eliminate the roles of oppressor and oppressed (Watts, Williams, & Jagers, 2003). To promote liberation, it is important to pay attention to values and to base reform on the people and their values within the community. Every group has some diversity with regard to values, and the most effective change begins with elements that are already valued by the group.

Stress, Coping, And Social Support

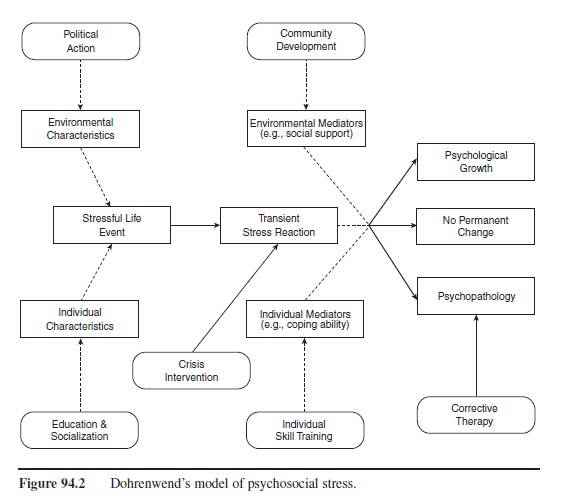

From a medical point of view, stress is a disturbance in the homeostatic balance of a person’s life. It can be induced by physical or psychological stimuli that produce mental or physiological reactions that may lead to illness. The concept of stress is useful to community psychologists in several ways. It focuses on the interface between a person and his or her environment, provides opportunities to craft interventions, and doesn’t imply a deficit perspective. In her presidential address to Division 27, Barbara Dohrenwend outlined the model of stress shown in Figure 94.2. The boxes in boldface represent the relation between stress and adjustment. The boxes that are not boldfaced represent the individual and environmental contributions to stress. The circles on the periphery show avenues for intervention. According to the model, the factors that contribute to stress are life events, individual characteristics, and environmental characteristics.

Factors That Contribute To Stress

Figure 94.2 Dohrenwend’s model of psychosocial stress.

Figure 94.2 Dohrenwend’s model of psychosocial stress.

Life events can exert a cumulative effect on an individual’s stress level. Coping with the death of a loved one while raising children and going to school can add up in a way that makes someone’s cutting in front of you in line unbearable. Life events differ in terms of the severity of the event; the frequency of the event’s occurrence, which ranges from daily hassles to major disasters; the regency of the event; and the valence of the event, which is related to the amount of life change required to cope with the event. Finally, life events differ in terms of their predictability, the amount of control we have over the event, and how typical the event is in our lives.

Several individual factors affect our reactions to stressors. As indicated in Dohrenwend’s model, individual characteristics can affect the occurrence of events as well as how stress is resolved. An individual factor that can affect the occurrence of an event is social status, because many people in the lower economic class have high-stress, unstable jobs. An individual mediating factor is locus of control. People with an internal locus of control believe that they affect what happens to them, whereas those with an external locus of control believe that fate, or luck, or powerful outside forces control what happens to them.

Environmental factors can affect the stress-coping relation in two ways: the occurrence of stressful events and the ways in which stress is resolved. For example, an environmental factor that causes stress would be dysfunctional family relationships. A mediating factor would be social support systems, which refers to the interpersonal connections and exchanges among individuals that are perceived as helpful by the recipient and the provider. Support can come in the form of emotional support or tangible support, which might be in the form of material support.

Coping Techniques

In addition to social support, there are several approaches designed to assist people in coping with stress, including crisis intervention, individual skill training, and mutual help groups. The mutual help group brings together individuals who share a common concern and allows them to share their troubles and learn coping strategies from one another. Although many people believe that members run mutual help groups, most are professionally led (Lieberman & Snowden, 1993). These kinds of support groups often form around problems that many consider embarrassing or stigmatizing, including alcoholism, AIDS, spouse or child abuse, and certain serious medical conditions.

Prevention And Promotion

What do community psychologists mean by prevention? Prevention is based on the idea that there are actions that will avert more serious problems down the road. Our interest in prevention goes back as far as the public health movement of the 19th century (Bloom, 1979). At that time, doctors began to try to control or eradicate major infectious diseases through such measures as vaccination (e.g., small pox, measles) or improved sanitation (e.g., to prevent cholera or malaria). Early efforts to apply this paradigm to nonmedical issues include Head Start, one of the most popular prevention programs ever developed in our country.

Prevention takes place at several levels. Caplan (1964) makes the distinction between tertiary prevention, secondary prevention, and primary prevention. Tertiary prevention takes place after the problem has developed and is designed to minimize the effects of the disorder. Halfway houses are a good example of a tertiary intervention. Secondary prevention refers to early intervention that does not reduce the onset of a problem, but does attempt to “nip the problem in the bud.” Early intervention in schools with at-risk children is an example of a secondary prevention program. Of greatest interest to many community psychologists are primary prevention programs—those directed at individuals who do not yet have a problem but might develop a problem unless something is done. Vaccinations, water fluoridation, and Sesame Street are all examples of primary prevention programs.

Before implementing a prevention program, we must determine whom to target, and that decision is based on an assessment of who is at risk. Several generic risk factors have been identified including family circumstances (e.g., poor bonding to parents), emotional difficulties (e.g., low self esteem), school problems, interpersonal problems, issues of skill development (e.g., reading disability), constitutional handicaps (e.g., neurochemical imbalances), and the ecological context in which a person lives (e.g., poverty, crime, or racial injustice). In assessing risk factors, we should distinguish between predisposing and precipitating factors. Predisposing factors are longstanding characteristics such as individual traits (e.g., mental retardation), personal background factors (e.g., lower socioeconomic status), and family history (e.g., abusive parents). Precipitating factors are stressful occurrences that trigger the disorder (e.g., being bullied at school, breaking up with a partner, or failing the final exam). Four emerging areas for prevention research and action are school violence, delinquency, terrorism, and HIV/AIDS.

Empowerment

What do we mean by empowerment? In popular parlance, physical exercise, meditation, and power shopping have been described as empowering. In community psychology, empowerment is used to describe not efforts to promote personal growth but rather the process by which people, organizations, and communities become masters of their own fate (Rappaport, 1987). It is a process that shifts power and control downward in an effort to provide greater autonomy and discretion to those who have historically been out of the power structure. Empowerment is a process accomplished with others, not alone, although individuals, organizations, communities, and societies can become empowered. When empowerment occurs, members of a community possess a positive sense of community, participate in decision making, and emphasize shared leadership and mutual influence.

To understand the process of empowerment, it is useful to examine the many forms of power. French and Raven (1959) initiated the study of people’s bases for power. Power can come from a person’s position within a community or organization (position power) or from the unique qualities of the individual (personal power). There are four forms of position power: legitimate power, reward power, coercive power, and information power. Legitimate power occurs when members of the group recognize that someone has authority over them. Reward power stems from the ability to provide resources to others. Coercive power is the power to punish. Information power is based on the unique sources of information available to someone. There are also four forms of personal power: rational persuasion, referent power, expert power, and charisma. Rational persuasion is the ability to convince others of the value of your plan. Expert power is based on the degree of expertise an individual possesses. Referent power is based on liking and respect. Individuals with charisma have an engaging and magnetic personality that can articulate a vision for the future. In the process of empowerment, no one basis of power guarantees success, but the use of multiple sources improves one’s chances.

Resilience

A meta-analysis conducted by Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman (1998) found that research over many years indicated that the negative effects of child sexual abuse were not as pervasive, severe, and long-lasting as generally assumed. Rather than being seen by victims’ advocates as good news, their findings were met with resistance, anger, and a United States congressional condemnation. The point being made in the article was that some people are particularly resilient to adversity.

Resilience is a positive adaptation despite significant adversity. For community psychologists, there is no shortage of adversities to study. In the United States, 40 percent of our children experience divorce, 22 percent live in poverty, 29 percent have chronic illnesses or physical disabilities, 20 percent of females have been raped, and 5 percent suffer abuse (Sandler, 2001). Although these events can be devastating, there are children whose adjustment seems extraordinary. What provides these children with the resilience to overcome such hardships? Community psychologists such as Masten and Coastworth (1998) have identified an important triad of protective factors. The first factor includes aspects of the individual’s disposition that elicit a positive response from their environment. This could include an easygoing temperament, physical health, intellectual abilities, self-confidence, faith, or a special talent that is valued within the community. However, cross-cultural research demonstrates that the individual factors that protect individuals in one culture may not protect people in other cultures. For example, de Vries (1984) documented that although an easygoing temperament contributes to resilience in the United States, Masai infants who were temperamentally difficult had better survival rates during drought in Africa. The second factor includes aspects of the family that nurture children. This could include an authoritative parenting style that provides warmth, structure, and high expectations for achievement. The third factor is the support system outside the family, which can include schools, religious congregations, clubs, sports teams, and other youth organizations (e.g., Scouts, 4-H, and Campfire Girls).

Future Directions: Community Psychology In The 21st Century

Where is community psychology going in the 21st century? There are several important issues facing us. For example, as our growing population continues to place a strain on finite resources, the question inevitably arises: Are we decreasing Earth’s ability to sustain life? Factories pollute our air and water. We are rapidly depleting our supply of seafood. People litter even though we all know that someone will have to come and clean up our mess. These kinds of behaviors are characteristic of the commons dilemma, in which short-term personal gain conflicts with long-term societal needs (Hardin, 1968). If water is scarce, taking a shower may be good for you, but harmful to the rest of the people needing water. In these situations, the gains to the individual appear to outweigh the costs, which create a form of social trap (Platt, 1973). There are three types of social traps. The individual good/collective bad trap occurs when a destructive behavior by one person is of little consequence but when repeated by many, the result can be disastrous. Overgrazing, overfishing, and excessive water consumption are examples. The one-person trap occurs when the consequences of the action are disastrous only to the individual. For example, overeating seems momentarily pleasurable but has long-term negative consequences. The third type of trap is the missing hero trap. This trap occurs when information that people need is withheld. An example would be failure to notify nearby residents of a toxic waste spill.

One of the challenges of community psychology in the 21st century will be to address this question: How can the commons dilemma be avoided? There are already some promising approaches to this problem. One way to overcome the commons dilemma is to change the consequences of the behavior to the individuals involved by punishing what was previously reinforced, and rewarding what was previously punished. For example, many cities have created carpool lanes on highways, which allow faster movement for those who share their automobiles. A second technique is to change the structure of the commons by dividing previously shared resources into privately owned parcels. Fish farms are an example of this approach. Unfortunately, many of our common resources such as air and water cannot be privatized (Martichuski & Bell, 1991). A third technique is to provide feedback mechanisms so that individuals are aware when they are wasting precious resources (Jorgenson & Papciak, 1981).

Each of these techniques has its own costs, benefits, and ease of application. The least costly intervention is probably environmental education but it may be one of the least effective as well. Reinforcement and punishment can have strong short-term effects, but many of these effects can dissipate over time when the reinforcement strategy is discontinued. Perhaps the most promising techniques have to do with increasing communication, promoting group identity, and encouraging individual commitment to solving the tragedy of the commons.

Another area of growing concern is the plight of those who are marginalized and stigmatized by their communities. There are several new trends in community psychology that are bringing invigorating advocacy for social justice and social change. Recently, Conway, Evans, and Prilleltensky (2003) created an organization called Psy-ACT, which stands for Psychologists Acting With Conscience Together. This network brings together advocates for social justice who use media contacts and education to raise awareness about the effects of poverty.

Another growing trend is the growth in collaborative, participatory research and action, which has led Wandersman (2003) to propose the term Community Science for an interdisciplinary field designed to incorporate empirical research, program development, and everyday community practices. His focus is mostly on prevention and promotion but also includes policy advocacy and social change.

As you think about the type of communities in which you want to live, work, and raise a family, consider the words of Helen Keller: ” Until the great mass of the people shall be filled with the sense of responsibility for each other’s welfare, social justice can never be attained. . . . I am only one, but still I am one. I cannot do everything, but still I can do something; and because I cannot do everything, I will not refuse to do something that I can do.”

References:

- Albee, G. W. (1986). Toward a just society: Lessons from observations on the primary prevention of psychopathology. American Psychologist, 41, 891-898.

- Alinsky, S. (1971). Rules for radicals: A practical primer for realistic radicals. New York: Random House.

- Alpert, J., & Smith, H. (2003). Terrorism, terrorism threat, and the school consultant. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 14(3/4), 369-385.

- Barker, R. (1968). Ecological psychology. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Belsky, J. (1980). Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. American Psychologist, 35, 320-335.

- Bloom, B. L. (1979). Prevention of mental disorder: Recent advances in theory and practice. Community Mental Health Journal, 15, 179-191.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513-531.

- Campbell, R., & Wasco, S. (2000). Feminist approaches to social science: Epistemological and methodological tenets.American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 773-792.

- Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventive psychiatry. New York: Basic Books.

- Clark, K. (1955). Prejudice and your child. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Conway, P., Evans, , & Prilleltensky, I. (2003, Fall). Psychologists acting with conscience together (Psy-ACT): A global coalition for justice and well-being. The Community Psychologist, 36, 30-31.

- Dalton, J. H., Elias, M. J., & Wandersman, A. (2007). Community psychology: Linking individuals and communities. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Degirmencioglu, S. M. (2003, Fall). Action research makes psychology more useful and more fun. The Community Psychologist, 36, 27-29.

- de Vries, M. W. (1984). Temperament and infant mortality among the Masai of East Africa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 141, 1189-1194.

- Dillon, J. S., Burger, P. R., & Shortridge, B. G. (2006). The growth of Mexican restaurants in Omaha, Nebraska. Journal of Cultural Geography, 24, 37-65.

- Fairweather, G. W. (1967). Methods for experimental social innovation. New York: Wiley.

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a mod-ern group that predicted the end of the world. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- French, J. R. P., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150167). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162, 1243-1248.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Jorgenson, D. O., & Papciak, A. S. (1981). The effects of communication, resource feedback, and identifiability on behavior in a simulated commons. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 17, 373-385.

- Kramer, R. M., & Brewer, M. B. (1984). Effects of group identity on resource use in a simulated commons dilemma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 1044-1057.

- Lerner, M. J. (1970). The desire for justice and reactions to victims. In J. McCauley & L. Berkowitz (Eds.), Altruism and helping behavior (pp. 205-209). New York: Academic Press.

- Levine, M., & Levine, A. (1992). Helping children: A social history. New York: Oxford University Press. Lewin, K. (1935). A dynamic theory of personality. New York. McGraw-Hill.

- Lieberman, M. A., & Snowden, L. R. (1993). Problems in assessing prevalence and membership characteristics of self-help group participants. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 29, 166-180.

- Luke, D. (2005). Getting the big picture in community science: Methods that capture context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 185-200.

- Martichuski, D. K., & Bell, P. A. (1991). Reward, punishment, privatization, and moral suasion in commons dilemma. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21, 1356-1369.

- Masten, A. S., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 53, 205-220.

- McCubbin, H. I., & McCubbin, M. A. (1988). Typologies of resilient families: Emerging roles of class and ethnicity. Family Relations, 37, 247-254.

- Moane, G. (2003). Bridging the personal and the political: Practices for a liberation psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 91-102.

- Moos, R. H. (1976). The human context: Environmental determinants of behavior. New York: Wiley.

- Nelson, G., & Prilleltensky, I. (Eds.). (2005). Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Perkins, D. D., Crim, B., Silberman, P., & Brown, B. (2004).

- Community development as a response to community-level adversity: Ecological theory and strengths-based policy. In K. Maton, C. Schellenbach, B. Leadbeater, & A. Solarz (Eds.), Investing in children, youth, families and communities: Strengths-based research and policy (pp. 321-340). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Peterson, N. A., & Zimmerman, M. (2004). Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 129-146.

- Platt, J. (1973). Social traps. American Psychologist, 28, 641651.

- Putnam, R., & Feldstein, L. (2003). Better together: Restoring the American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15, 121-144.

- Rind, B., Tromovitch, P., & Bauserman, R. (1998). A meta-analytic examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse using college samples. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 22-53.

- Rudkin, J. K. (2003). Community psychology: Guiding principles and orienting concepts. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Sandler, I. N. (2001). Quality and ecology of adversity as common mechanisms of risk and resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 19-55.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and content of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19-i5.

- Stein, C. H., Ward, M., & Cislo, D. A. (1992). The power of a place: Opening the college classroom to people with serious mental illness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 20, 523-548.

- Taylor, S. E. (1989). Positive illusions: Creating self-deception and the healthy mind. New York: Basic Books.

- Triandis, H. C. (1972). The analysis of subjective culture. New York: Wiley.

- Wandersman, A. (2003). Community science: Bridging the gap between science and practice with community-centered models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 227-242.

- Wandersman, A., Kloos, B., Linney, J. A., & Shinn, M. (Eds.). (2005). Science and community psychology: Enhancing the vitality of community research and action [Special issue]. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(3/4).

- Wasco, S., Campbell, R., & Clark, M. (2002). A multiple case study of rape victim advocates’ self-care routines: The influence of organizational context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 731-760.

- Watts, R., Williams, N. C., & Jagers, R. (2003). Sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 185-194.

- Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J. H., & Fisch, R. (1974). Change; Principles of problem formation and problem resolution. New York: Norton.

- Wicker, A. (1969). Size of church membership and members’ support of church behavior settings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13, 278-288.

- Wolff, T. (2000). Applied community psychology: On the road to social change. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 771-777). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Wolff, T. (2004, Fall). Collaborative solutions: Six key components. Collaborative Solutions Newsletter. Retrieved from http://www.tomwolff.com

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.