This sample Compensation Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Compensation is a major domain within human resource management to which several disciplines contribute. Psychological approaches to financial compensation focus on the motivational force of pay, its potential to get organization members to learn new abilities and skills, and the conditions for perceiving pay systems and practices as fair. In industrialized countries, the structure of compensation in profit and nonprofit organizations is quite comparable. Two important components of compensation—job evaluation (which often determines base pay) and performance-related pay—are considered more closely. Research indicates, for instance, that job evaluation tends to grasp one common factor (extent of required education), whereas employees may perceive the evaluation outcome as a harness. Performance-related pay appears to be a rather vulnerable kind of system, particularly when performance appraisal is based on qualitative characteristics. Frequently, employees do not perceive a relationship between the appraisal result and the awarded bonus amount. When quantified critical performance factors are applied, this relationship becomes more clear. Also, rather small differences in pay affect the behavior at work more often than do large differences in pay.

Outline

- Psychological Perspectives

- The Design of Compensation

- Job Evaluation

- Performance-Related Pay

- Conclusion

1. Psychological Perspectives

Managers and employees in an organization often wonder whether its compensation systems and strategies affect the work behaviors of the organization’s members, individually as well as in teams, and the performance results of the organization at large. Psychologically, this theme can be addressed in more than one way. One approach is in terms of the conditions that make compensation more or less motivating, often relative to the motivating potential of other work characteristics. Characteristically, the motivational force of compensation is inferred from the organization members’ level of effort, achieved performance, degree of satisfaction, and opportunities for personal development as well as from the effectiveness of cooperative efforts. A slightly different approach concerns the extent to which compensation facilitates the learning of new abilities and skills rather than stimulating employees to maintain their former habitual working patterns. This second approach is also basic to the decision, in cases of complex processes of organization change, as to whether alterations in compensation should precede or follow these. A third approach is distinguishable as managers face, for instance, the need to cut costs and are considering whether another compensation package might help them to achieve this. In such cases, an important perspective is the fairness with which this may be brought about, both in the procedures followed and in the quality of the end result. Here again, it is vital to consider the conditions under which compensation affects performance results.

These (and other) psychological perspectives are becoming more meaningful as they are considered within the frameworks of particular compensation systems. Although there are huge differences among pay forms and systems, there is a comparable compensation design across industrialized countries. This design is outlined in the next section. Then, two main categories of systems—job evaluation and pay for performance—are discussed from the viewpoint of how psychological insights may help to better understand recurring problems.

2. The Design Of Compensation

Although there are great differences among industrialized countries in the amount of pay provided for particular jobs, the structure of compensation is quite comparable throughout the major part of the world. It is designed on the basis of most or all of the components described in what follows.

Although there are great differences among industrialized countries in the amount of pay provided for particular jobs, the structure of compensation is quite comparable throughout the major part of the world. It is designed on the basis of most or all of the components described in what follows.

2.1. Base Pay

The base pay component reflects the value of a job to an organization often with respect to the particular labor market of a country or region. In many cases, systems of job evaluation are used to appraise and order the value of most or all available jobs within an organization. These relative job values are subsequently categorized in classes to which particular wage and salary scales are tied. In other cases, managers monitor the salaries that are paid in referent organizations for particular jobs and apply these to achieve ‘‘market conformity.’’ Job values embody, to a large extent, how scarce particular abilities and skills—or competencies—are within a (national) labor market. Thus, base pay recognizes the (scarcity of) qualifications of a worker to fulfill a specific set of tasks.

2.2. Performance-Related Pay

The performance-related pay component bears on the appraisal of job performance. Characteristically, specific targets or standards are set, and these have to be met or passed before a particular bonus is awarded. When the quantity of work performance was dominant, targets applied to the number of ‘‘pieces’’ made (piece rate system) or the amount of time required to perform a particular task (tariff system). Current standards relate more often to performance quality, team effectiveness, sales value, client satisfaction, and the like. Through performance-related pay, employees are recognized for what they do (and don’t do) in their work and are often thought to be stimulated to improve their performance.

2.3. Fringe Benefits

The fringe benefits component reflects the labor conditions that apply to members of an organization. In Europe, fringe benefits usually relate to a collective labor agreement (within the framework of a country’s social security policy) and include both secondary (e.g., health insurance programs) and tertiary conditions (e.g., a company’s car lease program). In the United States, fringe benefits packages are much more organization specific, mirroring entrepreneurial and managerial views on appropriate provisions. Usually, their coverage is much more modest than in European countries. When a cafeteria plan is applied, organization members get the opportunity to select, on a regular basis (often annually), alternative labor conditions, trading less attractive options for more attractive ones. Fringe benefits mirror the views of entrepreneurs and union leaders (and society as well) on the required level of minimal security in work and life.

2.4. Incidental Pay

When deciding on matters of pay, managers in most countries must take into account various laws, regulations, and the specific organization’s tradition of established practices. This host of rules might make it very hard to quickly express recognition to employees who have performed beyond expectations, put in many more hours than agreed on to speed up deliveries, and so forth. Incidental pay provides managers with the opportunity to reward some employees directly when applicable. Usually, the awards are small (e.g., a lunch for two, a dinner party). However, incidental pay might also involve larger awards (e.g., a paid conference).

Countries differ to a large extent regarding the proportional amount of base pay within their organizations. In some countries, base pay may amount to more than 90% of an employee’s salary, whereas in other countries, base pay may cover approximately 50% of the salary. Moreover, opinions vary concerning the degree to which organization members’ incomes should be based on their performance and sensitive to the volatility of (consumer) markets. Because job evaluation (base pay) and pay for performance have an incisive effect on managers’ and employees’ behaviors at work, these two components are addressed in more detail in what follows.

3. Job Evaluation

There are many different systems of job evaluation in use. Common to most systems is that key jobs are described according to their content and accompanying standard work conditions and are subsequently analyzed and appraised in terms of a job evaluation system’s characteristics (e.g., required knowledge, problem solving, supervision). Frequently, a point rating procedure, in which numerical values are assigned to the main job features, is applied. The sum total of these values constitutes the ‘‘job value.’’ This approach is, to some extent, derived from the technique of job analysis, a well-known subject area within work psychology. Through job analysis, the work elements of a job (e.g., cutting; sewing) are carefully analyzed in terms of those worker characteristics that are required for successful job performance (e.g., abilities, skills, personality factors). The objective of any job analysis system is to grasp the essence of a job in terms of a variety of distinct ‘‘worker’’ and/or ‘‘work’’ qualifications. Would the latter objective also hold for job evaluation? Research shows that these systems usually measure one common factor: extent of required education. In practice, several (professional) groups in organizations tend to stress the relevance of particular job qualities (e.g., leadership behavior, manual dexterity and sensitivity for specific tools in production work) that are believed to have been underrated in a particular job evaluation system. But factor-analytic studies show that even when a job evaluation system is ‘‘extended’’ to include such particular job qualities, second and/or third factors—if they can be identified at all—have much in common with the first (general education) factor. In other words: job evaluation measures the educational background required for adequate decision making in a job. Although the concepts and wording of job characteristics in various job evaluation systems might seem to differ from one another, they tap into the same construct. This is also exemplified through the custom, in several countries, of using a simple arithmetic formula to translate job value scores from one system of job evaluation into the scores of another system.

Obviously, these procedures for determining job value and base pay level do have important implications. First, the process of translating work descriptions or characteristics into worker attributes is quite vulnerable because it requires psychological expert knowledge to determine the variety of attributes (e.g., abilities, aptitudes, skills) relevant to adequately perform a particular job. Research has shown repeatedly that ratings may be biased in various respects due to the ‘‘halo effect,’’ gender discrimination, implicit personality theory, and the like. This theory refers to a pattern among attributes that a particular rater believes exists. One example might be that somebody scoring high on emotional distance is thought to excel in analytical thinking, have a ‘‘helicopter view,’’ and engage in a structuring leadership style because the rater assumes such a pattern to be ‘‘logical.’’

Second, regardless of an individual worker’s personal conception of his or her job’s main content, that job’s value is determined mainly by the level and nature of the required educational background. Consequently, a worker may perceive the evaluation of his or her job as not representing the worker’s ideas about the job’s actual content but rather as being the outcome of a bureaucratic exercise. Related to this is a third issue: Job evaluation may be experienced as a ‘‘harness’’ (because it measures one factor nearly exclusively), especially when a fine-grained salary structure is tied to the job value structure. This characteristic often makes it difficult and time-consuming to adjust job value and base salary to changed conditions. Flexible procedures have been designed to accommodate these needs.

Fourth, the larger the base pay proportion, the more organization members may perceive their pay as meaningful to satisfying important personal needs, according to the reflection theory on compensation. This theory holds that pay acquires meaning as it conveys information relevant to the self-concept of a person. Four meanings are distinguished: motivational properties, relative position, control, and spending. However, meaningfulness often diminishes as employees reach the high end of their salary scale without having much expectation of improving their level of pay. This implies that although base pay may motivate employees initially to stay in their jobs and to maintain at least an acceptable level of performance, this motivational force may wear out the longer employees remain in their jobs without noticeable changes in their level of pay.

4. Performance-Related Pay

Research data and practical experience reveal that the introduction of a performance-related pay system is a time-consuming and rather complicated exercise. Evidently, performance-related pay may be successful in an organization, but there are also many instances where it fails to produce its intended effects. Many factors have to be considered, the most salient ones of which concern yardsticks of performance appraisal, anteceding conditions, size of pay differences, and some contingency variables (e.g., secrecy).

4.1. Performance Appraisal: Qualitative Versus Quantitative Yardsticks

In many companies, qualitative characteristics are used for the appraisal of individual performance such as creativity, innovation, and customer orientation. These are often alternatively called behavioral yardsticks, personality statements, or competencies. A major problem is their abstract and often heterogeneous nature, without a direct relationship to observable work behaviors. They require a supervisor to ‘‘translate’’ daily and less frequent work events and actions into the framework of abstract person concepts without paying due attention to the interaction between the work situation and individual attributes. Thus, the use of these qualitative yardsticks is very much subject to bias. Because performance appraisal often occurs rather infrequently– (e.g., semiannually, annually), this method of appraising individual performance is vulnerable in practice. Because this performance appraisal result is tied to pay (either as a step on the salary scale or as a bonus), each department’s supervisor is usually assigned a particular budget to control salary costs. The supervisor may award each employee with an equal share in the budget. However, performance-related pay is intended to reward differences in performance differentially. Characteristically, a normal distribution curve is applied to effectuate this, as Fig. 1 shows.

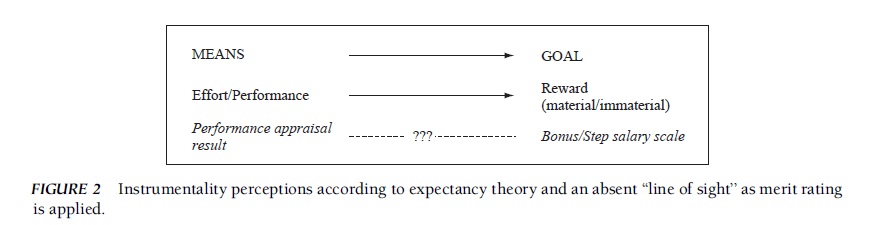

FIGURE 2 Instrumentality perceptions according to expectancy theory and an absent ‘‘line of sight’’ as merit rating is applied.

FIGURE 2 Instrumentality perceptions according to expectancy theory and an absent ‘‘line of sight’’ as merit rating is applied.

Figure 1 reveals that the great majority of employees earn an average bonus, whereas a few receive either a low bonus or a high bonus. Now assume that a supervisor wants to assign a relatively high bonus to some employees whose performance was beyond expectations. The restrictions posed by the budget necessitate that the supervisor assign a relatively low bonus to several other employees even though their performance often would not require this kind of intervention. How should the supervisor get this message across? This example illustrates why research data on this system of merit rating (or competence pay) show time and again that employees hardly perceive a relationship between their performance appraisal result and their bonus. There is hardly any ‘‘line of sight,’’ as Fig. 2 illustrates.

Figure 2 shows a core component of the expectancy theory on work motivation. Accordingly, the motivation to perform occurs as an individual perceives a relationship between his or her effort and performance level (expectancy) as well as a link between his or her performance level and one or more outcomes (instrumentality) that are attractive (valence). The figure highlights the principle of instrumentality and the often lacking line of sight—between the appraisal result and the resulting pay amount—as merit rating is applied. Not surprisingly, employees appear to be dissatisfied with their pay and consider the system (as well as the results it produces) to be unfair. The bonuses hardly recognize employees’ performance contributions, and supervisors often wonder whether the bonuses can ever motivate employees to perform better.

There is no recipe for success. But when quantitative yardsticks are used, performance appraisal is a much less vulnerable process. Such yardsticks relate to outcomes of performance or to the pursuit of particular behavioral actions (e.g., prescribed behavior patterns in risky work situations). Performance outcomes can be set through defining a job’s critical performance factors—two or three characteristics that represent the essence of a job (or job family) such as the number of billable training hours (for professional trainers) or the rate of recurring errors (for equipment repairers). Defining these factors is time-consuming; however, they can also be used for education and training, personal development, and career planning and can also be the focus of leadership behavior. Because critical performance factors should be vital to a job and sensitive to the job incumbents’ decisions and actions, they lend themselves to performance pay as well. Research and practical experience show that their line of sight is usually adequate.

4.2. Anteceding Conditions

A performance-related pay system requires a careful phase of preparation. At least the following four conditions should be met.

4.2.1. Study of Work

Through analyzing work processes within a unit or department, it should become clear whether work activities are adequately tuned to each other, work methods are well chosen, and the workforce is sufficiently trained. Within this context, critical performance factors may be set.

4.2.2. Norm Setting

For each performance factor, a specific target ought to be set. Research on goal-setting theory has revealed that difficult and specific goals (for individual tasks with single goals) lead to high performance as employees accept these targets and are provided with frequent feedback.

4.2.3. Performance–Pay Link

Performance-related pay may be awarded when a target has just been met, is clearly within reach, or has been surpassed. The performance–pay link may be proportional or either less or more than proportional. Expectancy theory would recommend rewarding achieved results as frequently as possible.

4.2.4. Control by Employees

Mutual trust appears to be one of the cornerstones for getting performance-related pay under way. Employees (and managers) concerned should be involved in implementing a new system—in its design, in its introduction, and/or in its daily administration. The more employees believe that they are in control of a system, the more they tend to evaluate the system as fair.

4.3. Size of Pay Differences

Suppose that the salary an employee earned this month is several euros or dollars less than the amount he made last month. Chances are great that the employee will notify the salary administration department. However, if the employee’s most recent paycheck would have shown a slightly higher salary than before, he probably would not have inquired about the difference. Upward and downward pay differences are not each other’s reverse in their behavioral effects. Some studies show that a pay increase of less than 3% is usually not perceived as significant by individual employees (regardless of the level of their previous earnings). A pay increases of 5% or more is considered to be worthwhile ‘‘to go for,’’ for instance, through better performance. However, if performance-related pay is applied, the size of the bonus appears not to be as important as the performance– bonus link per se.

Yet people at work often tend to compare themselves with others regarding their contributions to the work and the rewards they receive in return. Social comparison theory and equity theory have revealed that persons tend to compare their contributions–reward ratios with those of others who are in the most comparable situations (i.e., a referent). An employee who is comparing a valuable, relatively scarce attribute (e.g., his or her pay) with a referent wants to come out just a little bit higher. Such an outcome is quite motivating. But it hurts when the outcome is that the employee comes out a little bit lower. It is small differences that count.

4.4. Some Contingencies

Compensation systems and strategies operate within the social and cultural climate of an organization (and within the society at large). Consequently, many factors have been shown to affect compensation, one of which is pay secrecy. Many employers are quite open about their pay practices, whereas many others prefer to keep these secret. Whatever the arguments for such secrecy, it has an impact on the climate of trust and does not prevent organization members from making earnings comparisons among themselves. Research data show that such comparisons are unavoidably based on incomplete information, which may result in the misperception that the difference with the earnings of immediate subordinates is too small and that the difference with the earnings of superiors is too large. This may cause pay dissatisfaction. However, it is important to differentiate among three levels of ‘‘progressively open’’ information: the compensation system, its salary scales, and the level of individual earnings.

Also, differences in personality variables may be important. For example, individuals with higher scores on self-efficacy are more in favor of performance-related pay. Also, the higher the negative affect (i.e., the tendency to focus on negative life experiences that causes feelings of guilt and shame), the more disadvantageous effects a performance-related pay system will have.

5. Conclusion

Compensation in organizations provides a good example of multidisciplinary concerns. Compared with sociological, business administrative, and (especially) economic contributions, more psychological expertise would be most welcome. Recent work on the relationship between an organization’s general business strategy and its compensation strategy calls for better theories (and more research) on the choice of particular pay patterns. Psychology may profit greatly from the groundwork laid in other disciplines.

References:

- Dickinson, A. M., & Gillette, K. L. (1993). A comparison of the effects of two individual monetary incentive systems on productivity: Piece rate versus base rate pay plus incentives. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 14, 3–83.

- Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Balkin, D. B. (1992). Compensation, organizational strategy, and firm performance. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western Publishing.

- Lawler, E. E. (2000). Rewarding excellence: Pay strategies for the new economy. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

- Lawler, E. E. (2003). Treat people right. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

- Rynes, S. L., & Gerhart, B. (2000). Compensation in organizations: Current research and practice. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

- Thierry, H. (2001). The reflection theory on compensation. In M. Erez, U. Kleinbeck, & H. Thierry (Eds.), Work motivation in the context of a globalizing economy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Thierry, H. (2002). Enhancing performance through pay and reward systems. In S. Sonnentag (Ed.), Psychological management of individual performance. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.