This sample Conflict within Organizations Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Organizational conflict is a state that exists between two parties within an organization or between organizations, each with valued interests, in which one party’s (or each party’s) interests are violated, or in danger of being violated, by the other party.

Outline

- Introduction

- The Conflict Process

- Conflict Management Strategies

- Structural Conditions Affecting Conflict

- Conflict Outcomes

- Third-Party Intervention

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

Both within and between organizations, individuals interact regularly and almost as regularly experience conflict with one another. Sometimes the conflict between individuals is minor and unnoticed, whereas other times it is heated and drawn out. Whatever the case, the characteristics of conflict between individuals are important to understand for the sake of the individuals and the organizations where they work. This research paper provides a general understanding of interpersonal conflict in organizations and highlights some of the most recognized ideas that have been presented in research on the subject.

Interpersonal conflict is a state that exists between two individuals with valued interests in which one individual’s (or each individual’s) interests are violated, or in danger of being violated, by the other individual. It is an external form of conflict, as opposed to internal conflict where two or more of an individual’s interests are mutually exclusive (e.g., role conflict, conflict of interest).

Interpersonal conflict occurs between parties with opposing interests and can take three forms: normative, judgment, and goal. Normative conflict exists when one individual is offended by another individual’s behavior and believes that the latter should have behaved differently. Judgment conflict occurs when the individuals disagree over a factual issue (e.g., how a particular event transpired). Goal conflict is a situation in which two individuals are seeking mutually exclusive outcomes (e.g., how a slice of cake will be divided between them).

In 1992, Thomas, an extremely influential figure in conflict research, divided conflict into four factors that affect one another directly or indirectly: structural conditions, the conflict process, outcomes, and third-party intervention. Structural conditions make up the context of the situation in which conflict occurs and include the relatively stable factors of the parties and their surroundings. When conflict is triggered, the conflict process ensues with interactions between the parties involved. Both experiences and behaviors of the parties affect the process. Conflict outcomes are the result of the conflict process (specific episodes or series of episodes) and can include task outcomes (relevant to the matter of the conflict) and social system outcomes (relevant to the organization, the relationship between the parties, etc.). During the process, a third party may intervene. Third-party intervention is the involvement of an individual or a group whose primary concern is the resolution of the conflict as opposed to the substantive concerns of the conflicting parties.

Some third parties may, on resolution, change the structural conditions of the context, thereby influencing the resolution of future conflict. An example might be a manager who helps to resolve a dispute between two employees and then creates a policy to handle similar disputes in the future. Aside from these primary effects, feedback effects are likely to occur. For instance, the social system outcomes of a conflict episode are likely to alter structural conditions such that no two conflict episodes occur in identical environments.

2. The Conflict Process

When two individuals are experiencing conflict, the conflict process is the most apparent and explicit aspect of all that goes on between the parties. They are likely unaware of the contextual factors and their individual characteristics that set the conflict in motion. Although they have an idea of what they want out of the conflict, they are probably not considering all of the effects that the conflict will have beyond their individual goals. It is likely that each party is most interested in how to behave, and in how the other party should behave, in dealing with the conflict. The series of activities that run from initiating conflict to resolving it is referred to as the conflict process. The most popular research on the conflict process suggests that the conflict process is best observed at the level of the conflict episode. A conflict episode is a single engagement between two parties in conflict over some issue.

Two researchers developed and presented influential models of the conflict process: Pondy in 1967 and Thomas in 1992. Although both models have similar aspects, Thomas’s model gives attention to additional characteristics of the process such as the interaction of emotions, rational reasoning, and normative reasoning. The main aspects of this model are awareness that conflict exists, a series of thoughts and emotions leading to intentions that determine how the conflict will be handled, and interaction between the parties beginning with the first party’s behavior and continuing with the other party’s reaction. This leads to a continuous exchange cycle between the parties through thoughts/ emotions, intentions, and behavior that ends with resolution and outcomes.

Thomas defined conflict as ‘‘the process that begins when one party perceives that the other has negatively affected, or is about to negatively affect, something that he or she cares about.’’ At some point before an individual becomes involved in handling conflict with another person, that individual must first recognize that conflict exists. This point of first recognizing conflict is referred to as awareness. There will often be an event that triggers awareness such as an action or a statement made by the opposing party.

On becoming aware of conflict, an individual then begins to make sense of the situation by considering what is at stake and how the process should be handled. One aspect of this sense-making is defining the issue of the conflict. In addition to recognizing the issue at stake, an individual will begin to consider what outcomes are likely to result in a resolution that is acceptable to both parties.

Having defined the issue and considered possible settlements, an individual will then begin to reason both rationally and normatively in considering ways in which to handle the conflict that (a) are likely to result in efficiently and effectively achieving a beneficial resolution and (b) are perceived as acceptable and fair by the social environment. For example, if two individuals are in conflict over purchasing the last of a particular toy in a store before Christmas, the issue is apparent: Which of the two will get to purchase the toy? Rationally, one party may consider that attacking the other party and stealing the toy would efficiently and effectively result in a beneficial outcome. However, normatively, the social environment would not approve of this behavior. Therefore, the party should consider a more acceptable strategy for acquiring the toy.

The writer Oscar Wilde once said, ‘‘Man is a reasonable animal who always loses his temper when he is called upon to act in accordance with the dictates of reason.’’ Accordingly, individuals engaged in conflict are often affected by their emotions in addition to considering rational and normative reasoning. Both positive and negative emotions can affect how the opposing party’s behavior is interpreted and can amplify or dampen the influence of rational and normative reasoning. All of this will filter down to influence behavior. For instance, anger can result in aggression and negative interpretations of behavior, anxiety can lead to withdrawal, and innocent humor can decrease the negative effects of aggression and anger.

The interaction of an individual’s reasoning and emotions leads to a set of strategic and tactical intentions for handling the conflict episode. Strategic intentions refer to the overall goal one party has for the situation such as cooperating with or competing against the other party. Research on strategic intentions often refers to them as conflict management strategies and is discussed in the next section. Tactical intentions, on the other hand, are more specific goals or plans for achieving a beneficial outcome such as using a calm tone in presenting a case to keep the other party from becoming angry and focusing on the benefits that a proposed solution has for the other party. These intentions serve as guides for an individual’s behavior in managing conflict.

The intentions that an individual forms for dealing with a conflict episode will influence that party’s behavior. After the first party expresses behavior, the other party experiences a similar process of reasoning and expressing behavior as a response to the interpretation of the first party’s behavior. This is not necessarily a turn-based activity, although it can be in certain negotiation situations. Each party responds to the other party through the stages of thoughts/emotions, intentions, and behavior in a continuous interaction between the parties until some outcome is reached. This might not be the end of the conflict between these parties; however, it is the end of the conflict episode. The outcomes of conflict are discussed in a later section.

3. Conflict Management Strategies

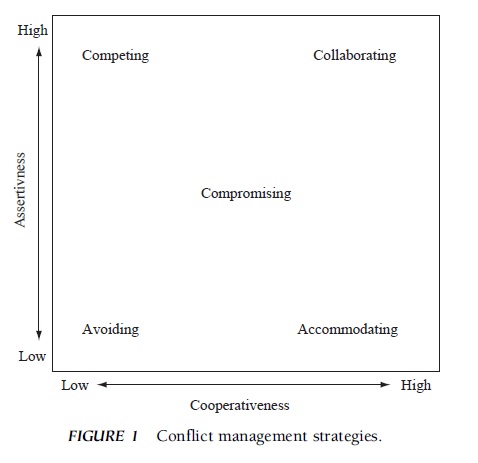

Five strategies for managing conflict have been used throughout numerous research studies on conflict: avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, and collaborating. These strategies are coordinated on a two-dimensional grid with the axes labeled either ‘‘concern for own interests’’ and ‘‘concern for other’s interests’’ or ‘‘assertiveness’’ and ‘‘cooperativeness’’ (Fig. 1). Thus, avoiding would represent either a low concern for self-interests and for other’s interests or low levels of assertiveness and cooperation, respectively.

The first conflict management strategy is accommodating, also referred to as obliging. Figure 1 shows that this strategy is low in assertiveness and high in cooperativeness—a lose–win strategy. In this case, one party chooses to allow the other party to satisfy its interests completely. One party may choose accommodation for several reasons. For example, the party may be unwilling to compete, may want to minimize losses, may consider the other party’s interests as more valuable, or may seek to prevent damage to the relationship between the parties. Accommodating can be an active strategy in which one party helps to satisfy the other party’s interests. It can also be a passive strategy in which inaction results in the satisfaction of the other party’s interests.

FIGURE 1 Conflict management strategies.

FIGURE 1 Conflict management strategies.

The second conflict management strategy is competing or dominating. This is the opposing strategy to accommodating and is classified as high in assertiveness and low in cooperativeness—a win–lose strategy. Competing is an active strategy in which one party attempts to satisfy its own interests, usually by preventing the other party from satisfying its interests when both parties’ interests are perceived as mutually exclusive. Competing may be more effective when quick and decisive action is vital, unpopular but important decisions must be made, an organization’s welfare is at stake and the right course of action is known, and/or the other party takes advantage of noncompetitive behavior.

Compromising or sharing is the third strategy shown in Fig. 1. In this case, one party is moderately assertive and cooperative. In contrast to either party winning or losing, compromising seeks a ‘‘middle ground’’ in which each party wins in part and loses in part. Compromising may be perceived as a weaker form of collaborating, but the use of compromising assumes a fixed amount of resolution that must be distributed, whereas collaborating seeks to determine both the size of the resolution and how it is to be divided. Compromising may be effective when opponents with equal power are committed to mutually exclusive goals, the issue is complex and at least a temporary settlement must be reached, interests cannot be fully sacrificed but there is no time for integration, collaborating and competing fail, and/or goals are important enough to fight for but not so important that concessions cannot be made.

The fourth conflict management strategy is avoiding. This strategy reflects low assertiveness and low cooperation—a lose–lose situation. With this strategy, one party chooses not to engage the other party in resolving the conflict in such a way that neither party is able to satisfy its interests. Avoiding may be a good strategy when an issue is trivial, there is no chance to satisfy a party’s own interests, the other party is enraged and irrational, and/ or others can resolve the conflict more easily.

The last of the conflict management strategies is collaborating or integrating. As the term implies, this strategy has an integrative focus. Parties using the collaborating strategy are classified as being both highly assertive and cooperative—a win–win attitude. In this case, the two parties attempt to work with each other to develop a resolution that will completely satisfy the interests of both parties. Although much of the research on conflict has proposed that collaborating is always the ideal conflict management strategy, others have suggested that there may be situations in which other strategies are more effective. Collaborating may be a more effective strategy when each party’s interests are too important to be compromised, full commitment to the resolution by both parties is desired, and/or there is sufficient time to resolve the conflict by integrating both parties’ interests.

Research on conflict management strategies has comprised a large portion of the total research on interpersonal conflict. The five strategies outlined here have become somewhat canonical in conflict research. Much research has validated the existence of these strategies and shown the advantage of a two-dimensional model over a one-dimensional (two strategy) model, but there have been no remarkable attempts to improve on or add to this model of conflict management. Although there is much room for more research to be done in this area of interpersonal conflict, it has not suffered from a lack of attention as other areas of conflict have.

4. Structural Conditions Affecting Conflict

The conflict process does not occur in a void; there are structural conditions that affect the process. Both the contextual situation and the parties involved have characteristics that may affect the various factors in the conflict process such as the choice of a conflict management strategy, inclusion of a third party, and norms for behavior. In 1992, Thomas suggested, ‘‘Whereas process refers to the temporal sequence of events that occurs in a system, structure refers to the parameters of the system—the more or less stable (or slow-changing) conditions or characteristics of the system that shape the course of those events.’’ Research has revealed several structural factors in both individuals and organizations that may have an effect on the conflict process. For instance, Wall and Callister’s review of conflict literature in 1995 discussed several individual and issue-related factors affecting conflict.

4.1. Individual Characteristics

Individuals constitute the primary parties in interpersonal conflict; therefore, it is likely that characteristics of those individuals will influence how the conflict episode is played out. It could be that differences in characteristics between individuals are the very reason for a conflict episode, for example, when two team members get into an argument because one is task oriented and the other is more relationship oriented. This difference can be the root of a series of events that result in conflict. Similarly, these differences may lead to each party handling the episode in a different way. Thus, individuals have stable or slow-changing characteristics that can influence conflict and the conflict process.

One characteristic that affects conflict is an individual’s culture (i.e., societal norms). Conflict is seen by some cultures as beneficial but is seen as detrimental by others. Thus, more assertive strategies are likely to be preferred by individuals from cultures seeing conflict as beneficial. Other individual characteristics affecting conflict are goal characteristics, stress, and the need for autonomy. An individual with high aspirations or extremely rigid goals is more likely to engage in conflict due to increased awareness of possible impediments to his or her goals. In addition, an individual whose goals are interdependent with another person’s goals is more likely to engage in conflict because the latter person’s behavior has an impact on the former person’s ability to achieve a goal. Stress may also lead to greater conflict due to the tension that an individual experiences, much like a rubber band pulled tight and ready to snap. Finally, if an individual has a high need for autonomy and another party makes demands that infringe on that autonomy, there is an increased likelihood of conflict.

Another individual characteristic that affects conflict is personality. For example, ‘‘Type A’’ and ‘‘Type B’’ personalities are likely to manage conflict in different ways given that Type B individuals are less competitive, less temperamental, and more patient. Studies by Antonioni in 1998 and Moberg in 2001 examined the effects of the ‘‘Big Five’’ personality factors—Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism— on preference of conflict management strategy. For instance, avoiding seems to be preferred by individuals with low Extraversion and low Conscientiousness, collaborating is preferred by those with high Extraversion and high Conscientiousness, and competing is associated with low Agreeableness.

Self-esteem has received considerable attention in conflict research. Research has shown that individuals with high self-esteem value satisfying both their own concerns and their counterparts’ concerns. These individuals are also more confident that collaboration is possible and are less likely to become defensive, a condition that negatively affects collaboration. Thus, individuals with high self-esteem are more likely to use collaboration in managing conflict. Other individual factors affecting conflict include locus of control (internal may provide greater confidence for resolving conflict), dogmatism (high levels may limit the flexibility of resolution possibilities), and stage of moral development (higher stage individuals are more likely to use collaboration). The individual characteristics presented here do not represent a comprehensive list of individuals’ structural variables that may affect conflict. However, these are some that have been addressed in research. Primarily, the discussion presented here suggests that it is important to consider more than the issue when trying to understand a conflict episode. The individuals themselves may have characteristics that contribute to both the triggering of the conflict episode and its management.

4.2. Organizational Characteristics

Conflict does not occur in a vacuum; rather, it occurs in some sort of interactive setting such as the workplace. Much of the research presented here (and in general) has concentrated on conflict occurring in an organizational context. Thus, much research has focused on examining the characteristics of organizations that influence conflict and its management.

Task characteristics may affect how a party manages conflict. When performing competitive tasks, an individual may be more likely to either compete or avoid. However, when performing a cooperative task within a group setting, collaborating and compromising are more likely to be used to manage within-group conflict. In addition, if the individual is performing a task that is highly interdependent with the other party’s task, he or she is more likely to prefer a collaboration strategy.

In addition to these, organizational culture and norms are likely to affect both parties’ behaviors during conflict. For instance, some conflict management strategies may be taboo within an organization. Rules and procedures are likely to affect conflict management as well because these can constrain certain behaviors while requiring other behaviors.

Structural conditions are considered fixed in the short run during the conflict process. However, in the longrun, structural conditions may be manipulated to make the conflict process more effective for the parties and the organization of which they are members. Some structural conditions can be affected by individual or organizational intervention. That is, parties can make adjustments to these conditions to influence how conflict is managed when it occurs. For instance, if increased stress results in undesirable behaviors and outcomes of a conflict episode, an organization may benefit by fostering an environment of low stress for its members. Intervening in this way can improve the way in which conflict is managed throughout the organization. Understanding individual and organizational characteristics that influence conflict can help managers and organizations to deal with conflict more effectively.

5. Conflict Outcomes

During a conflict episode, the primary parties and any third parties are continually working toward some sort of resolution. The ideal or acceptable outcomes of a conflict episode are likely to be related to the type of conflict management strategy employed by a primary party or to the type of intervention used by a third party. However, a conflict episode may have outcomes that go beyond what is expected by the parties involved. Conflict has several distinct types of outcomes: task, performance, and structural. Task outcomes include the resolution of the issue and the direct repercussions of the specific episode. Conflict can also have an effect on individual or group performance, for better or for worse, in the case where the conflict occurs in an organizational context; thus, performance is related to the direct repercussions portion of task outcomes. Finally, the effects of the episode on structural characteristics are a third distinct outcome. Thus, the three categories of outcomes that are discussed here are issue resolution, performance outcomes, and structural characteristics.

Issue resolution outcomes are related to the types of strategies employed to manage conflict. Much of the negotiation literature suggests that an agreement can result in either a distributive outcome or an integrative outcome. In addition, a third possibility is an impasse, that is, no agreement at all. A distributive outcome is one in which there is a fixed resolution that is either taken wholly by one party or somehow divided between the parties. An integrative outcome, on the other hand, is one in which the parties create an arrangement in which both parties are able to fully or significantly achieve their goals in resolving the conflict. This seems to be an ideal outcome, but in some situations integrative outcomes are not possible. In such cases, impasses and distributive outcomes are the only possibilities.

Jehn has contributed greatly to the research on performance outcomes of interpersonal conflict in organizations. Increased or decreased performance is a conflict outcome of which the primary parties might be unaware. That is, during conflict or as a result of conflict, each party’s performance in an organization may either suffer or benefit. Two types of conflict with differing effects on performance in organizations are task conflict and relational conflict. Task conflict is concerned with the content and goals of the work itself such as a disagreement between managers on which market to enter next. Relational conflict focuses on the interpersonal relationship between the parties such as one party having a personal vendetta against the other party.

Moderate to high levels of task conflict appear to result in better performance in an organization. This is likely due to the fact that when bad or less effective ideas are opposed, countering with good or more effective ideas is likely to have a positive effect on performance. On the other hand, relational conflict has a negative effect on an individual’s performance, probably due to the distractive effects of interpersonal feuding. In addition, each type of conflict is unique, with one type of conflict rarely transforming into the other (e.g., task conflict becoming relational conflict). This suggests two important points. First, an individual’s work performance is affected by conflict. Second, whether an individual’s work performance is affected positively or negatively by conflict depends on whether the conflict faced is task conflict or relational conflict.

When a conflict episode ends, the effects of the episode can affect future conflict episodes by influencing or changing characteristics of the parties or the organization. For instance, in 2000, Frone found that conflict with a supervisor can cause a worker to be less committed to an organization and can lead to lower job satisfaction and increase a worker’s intention to quit. Similarly, a particularly influential conflict episode can lead to instituting or changing organizational policies on how conflict is handled such as creating an ‘‘open door’’ policy and requiring managers to oversee conflicts between coworkers. Thus, one unintended outcome of a conflict episode might be changes in individual or organizational characteristics that may linger and have important effects on future conflict episodes involving those parties or within that organization.

This suggests that conflict outcomes can be intended or unintended, direct or indirect, and beneficial or detrimental. It is likely that some of the outcomes of a conflict episode will be unintended such as performance outcomes and structural changes. The intended outcome, usually the issue resolution, may be the primary or only focus of a party engaged in a conflict episode. However, it is important for the two parties to recognize that conflict can lead to unintended detrimental outcomes that can outlast the intended beneficial outcomes they are trying to achieve. It is even more important for an organization to recognize that internal interpersonal conflict can result in detrimental outcomes for the firm, requiring third parties to intervene on behalf of the organization’s interests and for the benefit of the two parties.

6. Third-Party Intervention

In some situations, the two parties involved in conflict need assistance in reaching a resolution. For instance, if each party refuses to make any concession and neither party can exert influence over the other party, the result is an impasse. If a resolution is necessary, a third party may get involved to assist in resolution. In other instances, resolution of the conflict may have an effect on organizational interests and a third party may get involved to look out for those interests. Because third parties are often involved in managing conflict, it is important to understand the ways in which third parties can help (or hinder) the management of conflict. It is also helpful to understand what factors affect how third parties will intervene and the effects of such intervention on the organization and the primary parties.

6.1. Methods Of Intervention

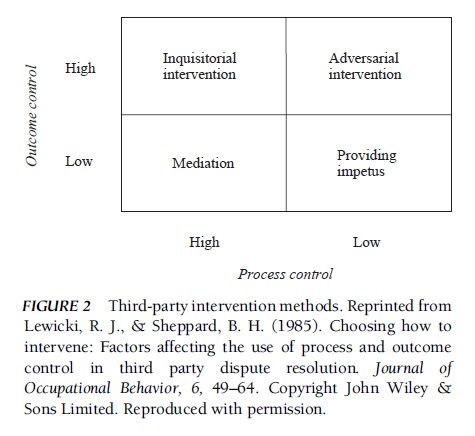

Two aspects of a conflict situation are relevant to third-party intervention: the conflict process and the resolution or outcome of the conflict episode. Process intervention is primarily concerned with managing the manner in which the primary parties interact. Outcome intervention is a matter of whether the third party has any control over the final decision regarding resolution. In 1985, Lewicki and Sheppard presented a set of third-party intervention methods, each of which exerts high or low process or outcome control. These intervention methods can be seen in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2 Third-party intervention methods.

FIGURE 2 Third-party intervention methods.

Using high outcome and process control is referred to as inquisitorial intervention and has been shown empirically to be the most common form of intervention employed by managers in dealing with conflict between subordinates. Using this type of intervention, a third party is likely to direct the interaction between the primary parties, deciding what information should be shared, deciding what is relevant or irrelevant, and possibly instructing parties as to how they should behave during the process. The third party is then likely to decide on a good resolution independently and to enforce this on the primary parties.

High outcome and low process control by a third party is referred to as adversarial intervention and is also a common method of intervention used by managers. This method is compared to the American judicial system in which parties present arguments and evidence with little or no direction from the third party. After each party has made a case, the third party makes the decision of how the conflict will be resolved and may even enforce the decision.

A less popular yet still used method of third-party intervention is the low outcome and low process control technique providing impetus. When using this method, a manager may listen to the primary parties to get a basic understanding of what the conflict is about and then suggest that the parties figure out a resolution themselves quickly or else some sort of punishment will be given or enforced. This is similar to a parent telling two children that they had better work out their differences or else they will be punished. A style with similar control as this method, yet more constructive and less threatening, is a method in which the third party listens to disputants’ views, incorporates their ideas, and asks for resolution proposals from the primary parties.

The low outcome and high process control method, or mediation, has been normatively described as the ideal means of third-party intervention but is rarely, if ever, used by managers in handling conflict between subordinates. It is suspected that this type of intervention is not used due to the large time investment required to direct the conflict process yet allow the primary parties to decide on a mutually beneficial resolution. Managers may prefer the other three methods of intervention so as to bring the conflict to a swift conclusion.

A third party is more likely to exert greater outcome control when time pressure is high, when the two parties are not expected to interact frequently in the future, and when the conflict outcome will have an impact on other parties and/or the organization. Greater process control is more likely to be used when the parties are less likely to interact in the future. Thus, it is suggested that managers are likely to use inquisitorial intervention when there are disputes between subordinates who do not interact very often. In addition, managers as third parties are more likely to use more autocratic (high control) methods than are peers as third parties.

6.2. Outcomes of Intervention

How does one determine to what degree third-party intervention has succeeded? The effectiveness of a third party’s involvement can be interpreted according to the achievement and quality of a resolution or according to the primary parties’ perceived fairness of the process and outcome. Much of the research on the effects of third-party intervention focuses on the latter. Because third parties can vary in the amount of control exerted over the conflict process and outcome, the primary parties can have different perceptions about the fairness of the process and the outcome.

Procedural justice refers to the degree to which a party perceives that the conflict process was handled fairly by a third party. A party is more likely to perceive the process as fair if a compromise is reached or if the outcome is otherwise favorable to that party. In addition, a party is likely to perceive greater procedural justice when a third party uses mediation, which is a more facilitating role. Providing impetus and inquisitorial intervention may lead to negative perceptions of fairness in the conflict process because these roles are more autocratic.

Distributive justice refers to the degree to which a party perceives the outcome of an episode as fair. In a similar reflection of procedural justice, a party is more likely to perceive the outcome as fair if a compromise is reached or if the outcome is favorable to that party. Therefore, it is no surprise that a party is more likely to perceive an outcome as unfair when the outcome favors the other party. Unlike procedural justice, however, the method of intervention does not appear to have an impact on perceived fairness of the outcome. Research has shown that a party is more likely to perceive the outcome as fair if the process is perceived as fair.

Another possible outcome of a conflict episode is the lack of reaching a resolution, that is, an impasse. The use of autocratic intervention by third parties often increases the chances of impasses or one-sided resolutions, whereas facilitating methods of intervention often increase the chances of compromise resolutions. In addition, an impasse is more likely if a peer, rather than a manager, takes on an autocratic third-party role.

7. Conclusion

Interpersonal conflict is an unavoidable aspect of organizational life and can have a substantial impact on individuals and organizations. As noted in this research paper, conflict can affect task outcomes, performance, and organizational structure. Thus, learning to manage conflict is a worthwhile investment for both individuals and organizations.

This research paper summarized information that may help to develop a general understanding of interpersonal conflict in organizations. The conflict process was first described in an effort to elucidate the sequence of a conflict episode. Five conflict management strategies were discussed along with suggestions as to when each might be more appropriate. Individual and organizational characteristics that may influence both the development and management of a conflict episode were presented. The effects or outcomes of conflict were noted, as were the possibilities for third-party intervention. Because interpersonal conflict is inevitable, the challenge for individuals in organizations is to use this information to manage conflict more effectively such that positive outcomes are obtained.

References:

- Antonioni, D. (1998). Relationship between the Big Five personality factors and conflict management styles. International Journal of Conflict Management, 9, 336–355.

- Blum, M. W., & Wall, J. A., Jr. (1997, May–June). HRM: Managing conflicts in the firm. Business Horizons, pp. 84–87.

- Brockmann, E. (1996). Removing the paradox of conflict from group decisions. Academy of Management Executive, 10,61–62.

- Frone, M. R. (2000). Interpersonal conflict at work and psychological outcomes: Testing a model among young workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 246–255.

- Jehn, K. A. (1997). A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 530–557.

- Karambayya, R., & Brett, J. M. (1989). Managers handling disputes: Third-party roles and perceptions of fairness. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 687–704.

- Karambayya, R., Brett, J. M., & Lytle, A. (1992). Effects of formal authority and experience on third-party roles, outcomes, and perceptions of fairness. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 426–438.

- Lewicki, R. J., & Sheppard, B. H. (1985). Choosing how to intervene: Factors affecting the use of process and outcome control in third party dispute resolution. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 6, 49–64.

- Lynch, D. (1997, May). Unresolved conflicts affect bottom line. HRMagazine, pp. 49–50.

- Moberg, P. J. (2001). Linking conflict strategy to the FiveFactor Model: Theoretical and empirical foundations. International Journal of Conflict Management, 12, 47–68.

- Mushref, M. A. (2002, November). Managing conflict in a changing environment. Management Services: Journal of the Institute of Management Services, pp. 8–11.

- Oetzel, J. G. (1999). The influence of situational features on perceived conflict styles and self-construals in work groups. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23, 679–695.

- Pondy, L. R. (1967). Organizational conflict: Concepts and models. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12, 296–320.

- Pruitt, D. G. (2001). Conflict and conflict resolution, social psychology of. In N. J. Smelser and P. B. Baltes (Eds.) International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences. San Diego: Elsevier Science.

- Rahim, M. A., Buntzman, G. F., & White, D. (1999). An empirical study of the stages of moral development and conflict management styles. International Journal of Conflict Management, 10, 154–171.

- Thomas, K. W. (1992). Conflict and negotiation processes in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 651–717). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Van Slyke, E. J. (1999, November). Resolve conflict, boost creativity. HRMagazine, pp. 132–137.

- Wall, J. A., Jr., & Callister, R. R. (1995). Conflict and its management. Journal of Management, 21, 515–558.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.