This sample Cross-Cultural Applied Psychology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

All human behavior is influenced by the culture in which a person develops. Thus, there can be no complete account of psychological phenomena without taking the cultural context into account. This claim applies not only to the findings of psychological researchers, but also to practitioners, who must consider the cultural settings of their applications as well as the cultural roots of the behavior.

Outline

- Definition of Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Definition of Culture

- History of Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Methodology

- Dimensions of Cultural Variation

- Evaluation of Findings and Applications

1. Definition Of Cross-cultural Psychology

According to Triandis and Lambert (1980), ‘‘Cross-cultural psychology is the systematic study of behavior and experience as it occurs in different cultures, is influenced by culture, or results in changes in existing cultures.’’ And per Berry et al. (1997), ‘‘The field is diverse: some psychologists work intensively within one culture, some work comparatively across cultures, and some work with ethnic groups within culturally plural societies.’’

Some think of culture as an independent variable that influences psychological processes, and some emphasize that culture and psychological processes are mutually constituted, i.e., ‘‘make each other up.’’ Berry argued that culture is both outside and inside the individual. It is independent of the individuals who arrive into a culture and become incorporated into a culture through the process of enculturation; but individuals also incorporate the culture through the same process, so that it also becomes an organismic variable, ready to be transmitted anew to other arrivals. In 2000, a special issue of the Asian Journal of Social Psychology discussed the similarities and differences between indigenous, cultural, and cross-cultural psychology, which reflect these differences in point of view.

2. Definition Of Culture

The conceptualization of culture is by no means a simple matter. One possible way to think about culture is that ‘‘culture is to society what memory is to individuals,’’ as per Kluckhohn (1954). It includes what has worked in the experience of a society, so that is what was worth transmitting to future generations. It includes both objective elements, such as tools, bridges, chairs, and tables, and subjective elements such as norms, roles, laws, religions, and values.

Sperber used the analogy of an epidemic. A useful idea (e.g., how to make a tool) is adopted by more and more people and becomes an element of culture. Barkow, Cosmides, and Tooby (1992) distinguished three kinds of culture: metaculture, evoked culture, and epidemiological culture. They argued that ‘‘psychology underlies culture and society, and biological evolution underlies psychology’’ (p. 635). The biology that has been common to all humans, as a species distinguishable from other species, results in a metaculture that corresponds to panhuman mental contents and organization. Biology in different ecologies results in ‘‘evoked culture’’ (e.g., hot climate leads to light clothing), which reflects domain-specific mechanisms that are triggered by local circumstances and leads to within group similarities and between groups differences. What Sperber describes Barkow et al. call ‘‘epidemiological culture.’’

Elements of culture are shared standard operating procedures, unstated assumptions, tools, norms, values, habits about sampling the environment, and the like. Because perception and cognition depend on the information that is sampled from the environment and are fundamental psychological processes, this culturally influenced sampling of information is of particular interest to psychologists. Cultures develop conventions for sampling information from the environment and for how much to weigh the sampled elements. For example, people in hierarchical cultures are more likely to sample clues about hierarchy than clues about aesthetics. Triandis argued that people in individualist cultures, such as those of most cultures of North and Western Europe and North America, sample elements of the personal self (e.g., ‘‘I am busy, I am kind’’) with high probability. People from collectivist cultures, such as those of most cultures of Asia, Africa, and South America, tend to sample mostly elements of the collective self (e.g., ‘‘my family thinks I am too busy, my co-workers think I am kind’’).

Just as individuals are incorporated into their primary culture through the process of enculturation, people may also become members of more than one culture through the process of acculturation, depending on life experiences.

2.1. Relationships with Other Perspectives

Cross-cultural psychology derives from both anthropology and psychology, taking various concepts, theories, and methods from each discipline. Because of this, the field is not unitary, but is composed of various perspectives. In our view, cross-cultural psychology combines two broad traditions. First, we use the comparative method (the ‘‘cross’’), making assumptions about the comparability of behavior (see below) and employing research and statistical methods drawn primarily from individual psychology Second, the field is concerned with the unique sociocultural contexts in which people develop and act (the ‘‘cultural’’), employing observational and narrative methods drawn primarily from cultural anthropology. The ‘‘cultural psychology’’ and ‘‘indigenous psychology’’ schools of thought emphasize this second perspective. However, in practice, both perspectives employ individual data, contextual data, and the comparative method in their work.

3. History Of Cross-Cultural Psychology

The first person to write anything relevant about this topic was probably Herodotus, during the 5th century BC. There are three histories of the field that start with Herodotus, who had the insight that all humans are ethnocentric. This is necessarily an aspect of the human condition, because most humans are limited to knowing only their own culture and thus are bound to use it as the standard for comparing their culture with other cultures. It is unfortunate that this is necessarily the human condition, because it makes people think that their norms and values are universally valid, and any deviations from them is seen as not only wrong but also immoral. Much human conflict can be traced to ethnocentrism. It is only when humans have experienced several other cultures that they become sufficiently sophisticated to see both the strengths and weaknesses of every culture and thus to become less ethnocentric.

Jahoda provided a detailed history of the field in which he discussed the work of Vico in the early 19th century, Wundt in the early 20th century, Tylor, Rivers, Boas, Luria, Bartlett, Bennedict, Vygotsky, and others. These writings were not central to the activities of most psychologists until the late 1980s and early 1990s, when many of the findings of cross-cultural psychology began challenging some of the theories of mainstream psychology.

The field became a distinct field of psychology in the early 1970s, when awareness of the need to stop being ethnocentric in research, and the need to develop measurements of psychological constructs that are both culturally sensitive and equivalent across cultures, became acute. Avoiding intellectual colonialism, such as the exploitation of data from other cultures without giving credit to local psychologists, resulted in an effort to develop a code of ethics for cross-cultural research. However, this code was not adopted by any association of psychologists because it was felt that it was overly strict and unrealistic and would inhibit research.

In the 1970s, most psychologists used an absolutist viewpoint. That is, it was assumed that all psychological discoveries were valid everywhere, and culture provided only minor modifications of these discoveries. In the 1980s, however, a number of researchers assumed more relativistic positions, in some cases even denying the psychic unity of humankind. Nowadays, a universalistic perspective is taken by many cross-cultural psychologists.

Journal publications with a cross-cultural psychology focus started in 1966. Leonard Doob, editor of the Journal of Social Psychology, and Germaine de Montmollin, editor of the International Journal of Psychology, announced that they would favor crosscultural articles. The Human Relations Area Files started a journal that year that eventually became Cross-Cultural Research. It is now the official organ of the Society for Cross-Cultural Research. The CrossCultural Newsletter (first edited by Triandis) was launched in 1967. It eventually became the Cross Cultural Bulletin of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. A directory of cross-cultural psychologists was first published by Berry in 1968. The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology (Walter Lonner, editor) started in 1970 and became the official organ of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. The Association pour la Recherche Interculturelle was established in 1984, and included French speaking cross-cultural psychologists. The Annual Review of Psychology introduced chapters reviewing cross-cultural work in 1973. The first edition of the Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology (Triandis, editor) appeared in six volumes in 1980–1981. The second edition (J.W. Berry, editor) appeared in three volumes in 1997.

3.1. Theory

The term absolutist was used to refer to a theoretical position that assumes that psychological findings are valid for all people everywhere; culture is thought to play little or no role in the development or expression of human behavior. Two other theoretical perspectives have been differentiated from absolutism. Relativism is essentially the opposite point of view: culture is so important in understanding human behavior that no psychological research or application can be done without knowing, and taking into account, the cultural context. An intermediate position (universalism) takes the position that human psychological processes are common, species-shared qualities; culture plays important variations on these basic processes during behavioral development and expression. In addition, absolutism tends to make comparisons freely; relativism generally avoids them; and universalism makes judicious comparisons (based on the underlying commonality) while taking care to understand the influence of culture. In a sense, the basic commonality makes comparisons possible (see discussion of equivalence, below), while the cultural variation in expression makes them interesting and worthwhile. In terms of the other perspectives or schools discussed previously, the cultural and indigenous approaches tend to be relativist, while the cross-cultural approach tends to be universalist.

4. Methodology

4.1. Levels of Analysis

Cross-cultural psychologists often work at different levels of analysis. For example, Hofstede has collected data from over 100,000 participants in more than 40 countries. By 2001, the data set was expanded to 50 countries. Responses to a sample of 40 and later 14 goals/value items were collected. He summed the responses to each goal/value item by the participants from each country. Then he factor-analyzed the 40 by 40 (or 14 by 14) matrix, based on 40 or 50 means. This is an ecological analysis and is very different from a within culture analysis, in which the matrix of correlations is based on the number of participants from that culture.

Readers may need an illustration of the fact that results at the cultural (or group) and individual levels of analysis can be different. Lincoln and Zeitz studied 500 employees divided among 20 social service agencies. They found that supervisory duties were positively correlated with professional qualifications across individuals but negatively correlated across agencies. The latter correlation was due to the fact that the members of the more professional agencies did not need much supervision.

4.2. Comparability and Equivalence

As was noted above, there are different viewpoints regarding whether comparisons are legitimate: relativists tend to object to them, absolutists tend to make them without restriction, and universalists employ them with caution, once certain conditions are met.

All acts of comparison (whether they be of cultures, institutions, or behaviors) require some common dimension along which phenomena can be judged. Apples and oranges can indeed be compared: on sugar content, juiciness, or price. The presence of such commonalities is a prerequisite for making a comparison; however, it is not enough. Cross-cultural psychologists seek to establish the comparability of two (or more) phenomena, using a number of ideas and techniques. One of these is equivalence, in which conceptual meaning and psychometric properties can be demonstrated to be sufficiently similar between two sets of data to be compared. It is no longer accepted practice to simply use an instrument, obtain a score, and apply a test of significance to the difference. While this has been known for a long time, it is still ignored by some writers who submit papers to the editors of psychological journals.

4.3. Emics and Etics

One approach to better controlling cross-cultural comparison is with the use of the concepts of emics and etics. All cultures categorize, but the categories that are used are culture specific. For instance, our eye is capable of discriminating 7,500,000 million colors, but we get along with a couple of dozen color names. Through the use of Munsell color chips, which provide an objective domain to which we can compare the way people in different cultures categorize colors, we can determine that the categories are not identical. The stimuli at the core of major color categories such as ‘‘red’’ are the same, but the periphery is not. So, even when we deal with something as simple as the identification of colors we must take cultural specificity into account. All categories are culture specific. We call these emic, from Pike’s use of phonemics and phonetics. But while most categories are emic, there are elements that are universal, which we call etic. In short, if we stick only to the core of each color range (the etic part) we can use the word ‘‘red’’ and its translations across cultures with reasonable equivalence. But there are regions of the category that are not equivalent across cultures.

Furthermore, there are languages that have very few color names. Some languages have only two words that are relevant to color that are more or less equivalent to white and black. When a language has three color names, it adds a word for red. If it has four or five names, then it also has words that are more or less equivalent to yellow and green. Languages that have progressively richer color vocabularies have a word for blue, then for brown, finally for purple, pink, orange, and gray.

People who do not distinguish between green and blue have difficulties in discussing differences in color between grass and the sky. If we study this domain and assume that they see color the way we do, we are likely to obtain distorted results. To avoid this problem, when we do a study we should talk to many people from each language to see how they cut the pie of experience. This would identify their emics for dealing with the particular topic. When we do that, some of their categories may also appear in other languages. Then, they may in fact be etics.

When we construct instruments such as tests or interview questions, or scales, we need to incorporate both emics and etics. The emics allows us to measure a phenomenon with cultural sensitivity, ‘‘the way the natives see it.’’ The etics allows us to compare the cultures. For example, a scale of social distance was constructed for Greeks and Americans in 1962. The scale values were standardized separately for each culture, and were made equal to zero for ‘‘I would marry this person’’ and 100 for ‘‘As soon as I have a chance I am going to kill this person.’’ The item ‘‘I would accept this person as a roommate’’ made sense only in the United States and had a scale value of 29.5. The item ‘‘I would accept this person in my parea’’ was a Greek emic, and had a value of 31.1. A parea is an intimate group of friends that meets almost daily to enjoy things together.

‘‘I would rent a room from this person’’ had a scale value of 57.5 in the United States and 42.8 in Greece, suggesting that in Greece it was a more intimate activity. In a culture such as India, where touching is a very important issue, one would use emic items such as ‘‘I would allow this person to touch my earthenware.’’ In a culture that has residential segregation, an item such as ‘‘I would allow this person to live in my neighborhood’’ would be a useful item to measure social distance.

We also need to consider the fact that often a construct used in the West has very different meanings in other parts of the world. For example, when people in the West use the concept of ‘‘intelligence,’’ they include the ideas of speed, successful adaptation, and effective completion of tasks. In parts of Africa, people think that to be intelligent means to be slow, sure, and not make mistakes. In other parts it includes the ideas ‘‘knows our traditions’’ and ‘‘does what the elders expect.’’ Among the Cree, a Native American tribe, ‘‘lives like a white’’ is conceptually close to ‘‘stupid.’’

4.4. Translation

In the construction of instruments that can be used equivalently across cultures, researchers need to use translation. This is a complex process.

5. Dimensions Of Cultural Variation

As has just been noted, comparisons require common dimensions on which they can be made. Beyond this simple dictum is a complex reality: there are many possible dimensions that could be employed in comparing cultures, institutions, and behaviors.

When we think of the relationship between culture and psychology, it is useful to use a metaphor from geography. We can discuss continents by describing mountain ranges, rivers, bays, etc. We can discuss countries by describing similar features, cities, villages, roads, etc. We can describe cities by describing roads, buildings, etc. We can describe villages by specifying the location of every building in relation to every other building. We can describe neighborhoods by discussing the economic, social relationships, religions, and political organizations of the residents, etc. Finally, we can discuss households by giving the biography of each member of the household, etc.

Note that as we move to lower levels of abstraction, we need more dimensions, details, specifications.

Psychologists deal with phenomena that are based on the common biology of humans, as it adapts to different environments (continents). Social psychologists also examine different environments (ecologies), for instance, social relationships in which people influence each other a great deal, as one finds in agricultural societies, or relatively little, as one finds among hunters and gatherers. Then, different behaviors can be identified. For example, there is more conformity in agricultural than in hunting environments. The societies that are agricultural have more inequality than the societies that engage in hunting and gathering.

Different disciplines focus on different levels of analysis. For example, literary productions describe events at the level of households. Anthropologists describe neighborhoods. Sociologists tend to describe cities and villages. We believe that all this work is valuable. All the information is necessary for a balanced understanding of the culture and psychology relationships.

In this section we focus on some of the dimensions of cultural variation that correspond to the level of continents. The data are obtained from different countries, though this is a very rough procedure because each country contains hundreds of cultures. Yet because regions of the world (e.g., Europe versus East Asia) have something in common, we can discuss the ways in which they are similar and different. Other work that we have no space to discuss is done at the other levels of analysis and is also valuable. The dimensions of cultural comparison are also called ‘‘cultural syndromes.’’

5.1. Complexity

We mentioned previously the contrast between hunters and gatherers and agricultural societies. Agricultural societies are more complex in the sense that they have more types of roles than hunting and gathering societies. As we move to modern information societies we find even more complexity, for instance, many more roles than in more simple cultures. If we consider all forms of specialization, e.g., the difference between medical specializations, in complex societies there are more than a quarter of a million roles.

5.2. Tightness and Looseness

Societies differ in the number of norms concerning correct behavior. Some have many norms, e.g., how to bow and how to smile, and others have few norms. Furthermore, some cultures punish severely those who deviate from norms whereas others are lenient. In tight cultures, there are many norms, and those who do not follow the norms are criticized or even killed. In loose societies, there are not many norms, and people who do not behave according to the norms are not punished. People are very likely to say ‘‘It does not matter’’ when they see a deviation from a norm. An example of a tight culture was the Taliban in Afghanistan. They killed people in large numbers for relatively minor deviations from arbitrary norms that they imposed on the basis of supposedly religious guidance. Some of these norms, such as not listening to music and not watching Western television, had nothing to do with religion. An example of a loose society, on the other hand, is Thailand, where people tend to smile even when employees do not show up for work as expected. The imposition on norms depends of the domain or the situation. For example, in the United States there is tightness concerning how to deal with banks, your checkbook, loans, mortgages, and the like. But now there is considerable looseness concerning who you can live with. Of course, there are also major individual differences. Some people are compulsive about their own and others’ behavior, while others are very lenient (e.g., any behavior is okay; it’s none of my business to criticize this behavior).

Hofstede identified a dimension he called uncertainty avoidance, which is related to tightness. Countries high on this dimension were Greece, Portugal, and Guatemala; low were Denmark, Jamaica, and Singapore. Subjective well-being was negatively correlated with this dimension, presumably because people in tight cultures are anxious about being criticized or punished for behavior that is not perfectly ‘‘correct.’’

5.3. Collectivism and Individualism

Societies that are both simple and tight tend to be collectivist. Societies that are both complex and loose tend to be individualist. Collectivism is a cultural pattern found especially in East Asia, Latin America, and Africa. It is usually contrasted with individualism found in the West, e.g., in Western and Northern Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Note, however, that any typology is an oversimplification; societies are not purely individualist or collectivist but some mixture of the two. The construct has been widely used in the study of cultural differences. Unfortunately, however, most of the research compared samples from North America versus East Asia. Thus, in the description of the attributes of the construct and its antecedents and consequents we rely too heavily on the differences between the United States and Canada on the one hand and China, Korea, and Japan on the other hand. We do not know if the information we present below applies equally to Africa and Latin America, though we suspect that much of it does. Much more research is needed on this topic.

Among the most important characteristics of the collectivist cultural pattern are the following:

- Individuals define themselves as aspects of a collective, interdependent with some ingroup, such as one’s family, tribe, co-workers, or nation, or a religious, political, ideological, economic, or aesthetic group.

- They give priority to the goals of that collective rather than to their personal ones.

- Their behavior is determined more often by the norms, roles, and goals of their collective than by their personal attitudes, perceived rights, or likes and dislikes.

- They stay in relationships even when the costs of staying exceed the advantages of remaining.

These are the defining attributes of collectivism. There are as many kinds of collectivism as there are collectivist cultures. To distinguish among collectivist cultures additional attributes are necessary.

Triandis summarized the literature that used that construct in social psychology, and Kagitcibasi provided a critical evaluation of the construct. Hofstede found that the United States, Australia, and Britain were highest in individualism and Panama, Ecuador, and Guatemala were highest in collectivism. Most Western countries are individualist and most East Asian countries are collectivist. However, gross national product per capita is correlated with individualism; thus, wealthy East Asian countries such as Japan are not as collectivist as one would expect from their geographic location.

Within any society there are individuals who behave like persons in collectivist cultures, called allocentrics. They contrast with those who behave like persons in individualist cultures, who are called idiocentrics. There are both allocentrics and idiocentrics in every society, but their distributions are different, with more allocentrics found in collectivist cultures.

Collectivism is maximal in relatively homogeneous societies, such as theocracies and monasteries, while individualism is maximal in heterogeneous societies that are very affluent. Thus, there will be few idiocentrics in monasteries and few allocentrics among Hollywood stars.

All individuals have access to cognitive systems that include both allocentric and idiocentric cognitions, but they sample them with different probabilities, depending on the situation. For example, if the ingroup is under attack, most individuals become allocentric. In the company of other allocentrics, the norms for allocentric behavior become salient, and individuals are more likely to sample allocentric cognitions. Some situations provide very clear norms about appropriate behavior (e.g., in a house of worship), while other situations do not (e.g., at a party). Individuals will be more allocentric in the former than in the latter situations. When the ingroup can supervise an individual’s behavior, norms are more likely to be observed, and the individual will be more allocentric. In one study, allocentrics and idiocentrics were randomly assigned to simulated organizations that were individualist or collectivist, and the degree of cooperation exhibited by the individuals was studied. It was found that cooperation was high when allocentrics were in a collectivist organization. In the other three cells of the experiment, there was very little cooperation. In short, both the personality and the situation were required to predict the behavior.

Collectivism can appear in all or none of the domains of social life. For example, it can be found in politics, religion, aesthetics, social life, economics, or philosophy, as was the case in China during the Mao period, or in none of these domains, as among Hollywood stars.

5.3.1. Antecedents of Collectivism

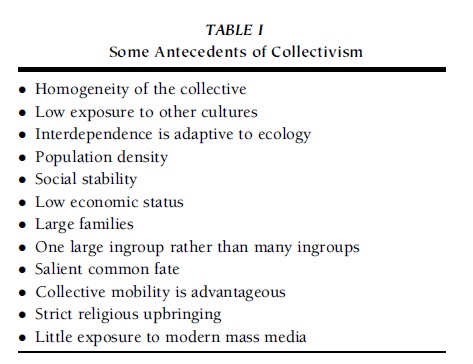

Some of the antecedents of collectivism are listed in Table I and are discussed below:

Homogeneity of the collective. If people disagree about the norms of proper behavior, or the goals that people should have, it is difficult for people to behave according to the norms of the group.

TABLE I Some Antecedents of Collectivism

TABLE I Some Antecedents of Collectivism

Low exposure to other cultures. People who know only one culture tend to be maximally ethnocentric, authoritarian, and submissive to ingroup authorities. Those who are more educated, traveled, and have lived with more than one cultural group develop idiocentric tendencies.

Interdependence is adaptive to ecology. People are more interdependent in agricultural societies than in information societies. For example, when the goal is to complete large projects such as irrigation canals or defensive walls, collectivism is more likely. In societies where people are financially interdependent, collectivism is high. People who can do their job when they are alone are more likely to be idiocentric.

Population density. In dense social environments, many rules that are designed to reduce conflict and ensure the smooth functioning of the group develop.

Social stability. When the collective is stable, it is more likely to develop agreements about norms, and to make sure that the norms are observed. There is evidence that the older members of all societies are more allocentric than the younger members.

Low economic status. The lower social classes tend to be more conforming to social norms than members of the upper classes. When resources are limited, one often depends on group members for assistance, especially in emergencies. These factors increase collectivism. On the other hand, in all cultures, those in positions of leadership tend to be idiocentric.

Large families. In large families it is not practical to allow each child to follow idiosyncratic schedules or to have much privacy. Many rules are enforced, and that creates collectivism.

One large ingroup rather than many ingroups. Those who only have one ingroup can channel all their energy into that group. Also, they cannot afford to develop poor relationships with members of that group, so they are more likely to observe its norms.

Salient common fate. Common fate with members of the ingroup (e.g., when the ingroup is under attack) increases collectivism. Time pressure for decisions has similar consequences.

Collective mobility is advantageous. If individual upward social mobility is not possible, then collective mobility may be used. Thus, individuals invest their energy in promoting the status of their ingroup.

Strict religious upbringing. Most religions require observance of a large number of norms and threaten to punish those who ignore these norms. That increases collectivism. Little exposure to modern mass media. U.S.-made television is widely available throughout the world.

Content analyses show that the themes used are highly individualistic (e.g., emphasis on pleasure, doing what the individual wishes to do even if that is inconsistent with the wishes of authorities). Countries where people have little exposure to Western mass media are more collectivist.

5.3.2. Consequences Of Collectivism for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation

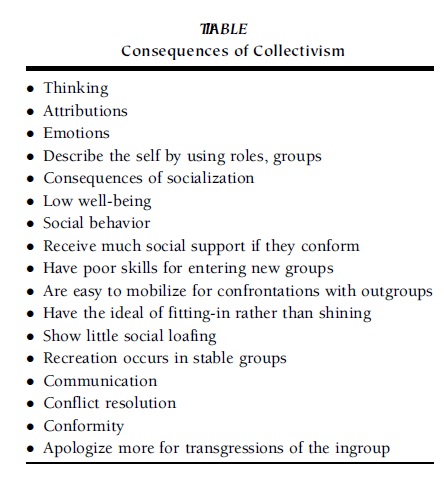

Marcus and Kitayama have reviewed much evidence showing the influence of collectivism on cognition, emotion, and motivation (see Table II).

Thinking. Nisbett, Peng, Choi, and Norenzayan examined a broad range of literature concerning thought patterns in ancient Greece and China, two cultures that correspond to the individualism–collectivism contrast. They argued that the Greeks thought analytically and the Chinese holistically. The Greek traditions influenced the West, which now uses logic, rules, and categories and sees the world as a collection of discrete objects, while the East sees the world as a collection of overlapping and interpenetrating substances. They reviewed much empirical work that contrasted Western and Eastern cultures, and found that the West focuses on objects and their attributes, while the East focuses on the context of objects and the relationships of objects and events to each other.

TABLE II Consequences of Collectivism

TABLE II Consequences of Collectivism

Western thought is linear, concerned with abstract analysis, and pays much attention to contradictions. Eastern thought is dialectical, experience-based, and pays little attention to contradiction. The West is more field independent; the East more field dependent. Explanations of events in the West focus on the attributes of the object, e.g., the attitudes, beliefs, and values of individuals as determinants of behavior; in the East, the focus is on the context of the object, e.g., group memberships, norms, and social pressures that influence the behavior of individuals. Numerous other cognitive patterns contrast these two kinds of cultures and show not only quantitative but also qualitative differences in thinking.

Attributions. Allocentrics make external attributions in explaining events, whereas idiocentrics show the opposite pattern. Thus, the idiocentrics make the fundamental attribution error (i.e., seeing internal rather than external causes for the behavior of other people, while the actors themselves see external causes as explanations of their own behavior more often than internal causes) more frequently than do allocentrics. Also, allocentrics attribute their successes to the help they have received from others and their failures to personal shortcomings (e.g., I did not try hard enough). Allocentrics tend to think that social environments are stable and individuals are easy to change so that they can fit into the environment; idiocentrics think that individuals are stable and social environments are easy to change.

Emotions. Members of collectivist cultures get angry when something unpleasant happens to ingroup members more often than when something unpleasant happens to themselves. They do not express negative emotions as often as do members of individualist cultures.

Description of self. When asked to complete 20 statements that begin with ‘‘I am .. .’’ members of collectivist cultures provide sentence completions that have more social content (e.g., I am a brother, I am a member of the Communist party) than do members of individualist cultures.

Socialization. In collectivist cultures, children are socialized to be obedient, be reliable, follow traditions, do their duties, sacrifice for the ingroup, and be conforming. An important value is self-control.

Low well-being. While members of all cultures are satisfied with their life, members of collectivist cultures are less satisfied than members of individualist cultures. Well-being tends to be correlated with individualism. This relationship persists even when statistically controlling for income.

Social behavior. Collectivists are extremely concerned with ‘‘saving face,’’ and even attempt to save the face of the persons with whom they are interacting. Preserving harmony within the ingroup and being pleasant in relationships with ingroup members are often important values. On the other hand, collectivists do not care much about their relationships with outgroups. They usually behave quite differently toward ingroup versus outgroup members, showing sacrifice and extreme cooperation with ingroup members and suspicion and hostility toward outgroup members.

Social support. Allocentrics report that they receive more social support and a better quality of social support than do idiocentrics. However, those who do not conform to ingroup norms are rejected, and may even be killed.

Poor skills for entering new groups. Members of collectivist cultures do not have good skills for entering new groups, because they are not socialized to do this. They are comfortable as members of their ingroups, thus they do not need to enter other groups.

Easy to mobilize for confrontations with outgroups. When ingroups are in conflict it is easier to arouse members of collectivist cultures to fight for the ingroup than it is to do so with members of individualist cultures. Ethnic cleansing is more often found in collectivist than in individualist cultures.

Have the ideal of fitting-in rather than shining. Allocentrics prefer to fit in and be like most others in their ingroup rather than shining and sticking out. Idiocentrics tend to be high in self-enhancement (i.e., report that they are better than most other people on most desirable attributes). Allocentrics tend to be modest when they compare themselves to others.

Show little social loafing. Allocentrics show little evidence of social loafing (i.e., the tendency to produce less when working in a group versus when working alone, if their output is not identifiable). They usually produce as much as possible when they work with ingroup members, but they do show social loafing if their co-workers are outgroup members.

Recreation. Members of collectivist cultures seek recreation in groups to a greater extent than members of individualist cultures (e.g., bowling rather than skiing).

Communication. Members of collectivist cultures rely on the context (e.g., distance between and position of bodies, eye contact, gestures, tone of voice) more than on the content of communications. For example, rather than saying ‘‘no,’’ they may serve incongruous foods in order to put across their negative message without causing the other person to lose face. When they describe a person they are likely to use context, e.g., ‘‘He is intelligent in the marketplace,’’ rather than decontextualized statements, such as ‘‘He is intelligent.’’ Silence is used more in collectivist than in individualist cultures. Compliments are not used as frequently as in individualist cultures. The languages of collectivist cultures do not require the use of ‘‘I’’ or ‘‘you.’’ Collectivists use more action verbs (e.g., he asked for help) rather than state verbs (e.g., he is helpful), which suggests that they use communications that make greater use of context, are more concrete, and place less emphasis on the internal attributes of the person.

Conflict resolution. Members of collectivist cultures avoid conflict with ingroup members, and in the case of disagreement they prefer silence to argument. They prefer mediation to confrontation.

Conformity. Members of collectivist cultures show more conformity than members of individualist cultures in experiments that measure conformity.

Apologize more for transgressions of the ingroup. Members of collectivist cultures apologize more when an ingroup member commits a crime than is common in individualist cultures.

5.3.3. Evaluation of the Construct

While people in collectivist countries indicate that they are less happy than people in individualist countries, individualism has been found to be associated with poor marital adjustment, thus high divorce rates, and more delinquency, crime, drug abuse, suicide, experimenting with early sex, and stress.

Naroll has reviewed much evidence that indicates that tight social groups are needed for social control and the good life. Diener and Suh suggest that ‘‘real happiness’’ depends on having many small positive experiences rather than having a few very intensive positive experiences. Thus, while people in collectivist countries may feel unable to do ‘‘their own thing’’ and thus report low levels of happiness at the moment they are asked if they are happy by the researcher, they may be happier in the long run. Thus, each cultural pattern has both positive and negative aspects.

5.4. Power Distance

Hofstede identified a dimension of cultural variation he called power distance. Cultures high on this dimension have members who see a large distance between those who have power and those who do not. Thus, for instance, people in such cultures fear disagreement with their superiors. Countries high on this dimension were Malaysia, Guatemala, and Panama. Countries low were Denmark, Israel, and Austria. This dimension was highly correlated with collectivism. It was also correlated with the level of corruption of the country.

5.5. Sex Differentiation

Hofstede has identified a dimension he calls masculinity– femininity. In feminine cultures, members of the culture attach more importance to relationships, to helping others, and to the physical environment than people in masculine cultures. In masculine cultures, people emphasize careers and money. The goals of men and women are more differentiated in masculine than in feminine cultures. National samples that emphasized male goals were found in Japan, Austria, and Venezuela, whereas the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands emphasized female goals. In the countries that were high in masculinity, men and women gave very different responses to Hofstede’s value questions, while in the countries that emphasized female goals, the answers obtained from men and women were the same. Similar differences were observed across occupations, with engineers giving masculine and secretaries giving feminine answers. The consequences of this cultural difference included such matters as people in masculine countries wanting brilliant teachers versus people in feminine countries wanting friendly teachers. Differences in politics were also identified. In masculine countries people supported tough policies toward poor people and immigrants. Economic growth was given priority over preservation of the environment in masculine countries. In feminine countries, compassionate policies toward the weak and the environment were given high priorities.

5.6. Dealing with Time

There are cultural differences in the way time is viewed and in the speed of life. People in countries that are rich, individualistic, and in cold climates move fast and arrive for appointments at the correct time. Those in poor, collectivist countries located in hot climates tend to move slowly and arrive for appointments late. For example, because in collectivist cultures interpersonal relations are very important, if a person who is on her way to an appointment meets a friend, the chances are that she will spend much time with the friend and be very late for the appointment. But it will not be necessary for her to apologize for being late, as most likely the other people at the appointment will also arrive late.

In all countries, cities are faster than rural environments. Levine devised a number of methods that objectively measured speed; for example, how fast do people walk in the street, how long does it take to mail a letter, how accurate are the clocks in public places. These measures were intercorrelated, showing concurrent validity. He took several samples on each measure in 31 countries. Switzerland, Ireland, and Germany were the fastest and Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico the slowest countries.

Hofstede introduced a measure of long versus short-term orientation. A long-term orientation was found in East Asia, among countries with a Confucian tradition, while a short-term orientation was found in the Philippines, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

5.7. Missing Topics

The relationship between culture and psychology is so extensive and complex that in this research-paper we were able to present only an introduction. Cultural differences in trust, although not discussed here, are especially important because in countries that are low in trust it is difficult to have economic development. Low trust is frequently found in collectivist cultures where outgroups are often seen as enemies. Because most people belong to outgroups, people in low-trust countries feel surrounded by enemies. A study by Bond, Leung, and 60 other researchers identified a factor that is related to distrust. Countries such as Pakistan and Thailand were high on this factor whereas most of the European countries were low. It is not clear at this time if economic development results in high trust or if high trust leads to economic development. It is likely that the relationship is reciprocal.

6. Evaluation Of Findings And Applications

Approximately 20 years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) approached the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology with what appeared to be a rather simple question: ‘‘What do you know, as cross-cultural psychologists, that can help the WHO to achieve its goal of Health for All by 2000?’’ A number of meetings were held to discuss, and to try to answer, this question. The result was a volume of topical appraisals and an evaluative overview of them. Dasen et al. concluded that there was considerable research based knowledge, but little that was readily applicable. Two reasons were advanced to explain this discrepancy. First, most knowledge acquisition is driven by a research orientation more than (even rather than) a view to eventual application: at the end of a project, there is often the question, ‘‘What do we do with all this?’’ Second, most research, even research that is explicitly cross-cultural, is rooted in one dominant psychological perspective (e.g., WASP, Western academic scientific psychology) that smacks of ethnocentrism, even if that is inadvertent.

A later approach was made to a broader range of questions that went beyond health to other domains of human activity. Once again we concluded that there was great potential but little actual achievement: a substantial knowledge base had not yet been applied. More recently, a number of authors addressed this question for a limited number of behavioral domains, and found that while progress had again been made, the gap between knowledge and practice remained wide. This state of affairs is not unique to cross-cultural psychology, but it is made more salient by the urgent need to use psychological knowledge in many parts of the world. Critical projects are needed in societies other than those in which the knowledge was generated.

One way to assist in the process of application is to present the knowledge base for findings that may qualify as ‘‘universals,’’ and hence that may be applicable across cultures. In such cases, the problem of cultural irrelevance or incompatibility may be reduced, even though the science–application gap may remain. Following the sequence in this research-paper, we can first make use of the knowledge provided by our cognate disciplines of cultural anthropology, linguistics, and sociology. These disciplines have established universals in sociocultural systems and institutions, ones that can be found in all societies. Some of these have been portrayed in Section 5. What we take from these is not that the variation hinders application, but that the common dimensions provide a basis for the cross-cultural use of various research findings.

From these other disciplines, we have also adopted theoretical perspectives (especially relativism and universalism) and concepts that provide foundations for our methodological tools (emics, etics, equivalence); other applications include cultural similarities and differences in organizational behavior. Finally, an important application is training people to learn how to interact successfully with those from other cultures.

References:

- Aberle, D. F., Cohen, A. K., Davis, A., Levy, M., & Sutton, F. X. (1950). Functional prerequisites of society. Ethics, 60, 100–111.

- Barkow, G., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (Eds.) (1992). The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Berry, J. W. (1969). On cross-cultural comparability. International Journal of Psychology, 4, 119–128.

- Berry, J. W. (1975). Applied cross-cultural psychology. Lise: Sets & Zeitlinger.

- Berry, J. W. (1976). Human ecology and cognitive style: Comparative studies in cultural and psychological adaptation. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Berry, J. W. (2000). Cross-cultural psychology: A symbiosis of cultural and comparative approaches. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 197–205.

- Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., & Pandey, J. (1997). Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 1, 3rd ed.) Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications. New York: Cambridge University.

- Brislin, R. (Ed.) (1990). Applied cross-cultural psychology. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Dasen, P. R., Berry, J. W., & Sartorius, N. (Eds.) (1988). Health and cross-culture psychology: Towards applications. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Diener, E., & Suh, E. M. (Eds.) (2000). Subjective well-being across cultures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 851–864.

- Frijda, N., & Jahoda, G. (1966). On the score and methods of cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychology, 1, 110–127.

- Greenfield, P. M. (1997). You can’t take it with you. American Psychologist, 52, 1115–1124.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. (2000). Modernization cultural change and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65, 19–51.

- Jahoda, G. (1992). Crossroads between culture and mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jahoda, G., & Krewer, B. (1997). History of cross cultural and cultural psychology. In J. W. Berry, Y. H. Poortinga, & J. Pandey (Eds.), Handbook of cross cultural psychology (2nd ed., pp. 1–42). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Kagitcibasi, C. (1997). Individualism and collectivism. In J. W. Berry, M. H. Segall, & C. Kagitcibasi (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (2nd ed., pp. 1–50). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Klineberg, O. (1980). Historical perspectives: Cross-cultural psychology before 1960. In H. C. Triandis, & W. W. Lambert (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 1–14). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Kluckhohn, C. (1954). Culture and behavior. In G. Lindzey (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 921–976). Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Lenski, G. E. (1966). Power and privilege: A theory of social stratification. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Levine, R. (1997). A geography of time. New York: Harper Collins.

- Lincoln, J. R., & Zeitz, G. (1980). Organizational properties from aggregate data: Separating individual and structural effects. American Sociological Review, 45, 391–408.

- Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

- Naroll, R. (1983). The moral order. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108, 291–310.

- Murdock, G. (1967). Ethnographic atlas. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Shweder, R. A. (1990). Cultural psychology: What is it? In J. W. Stigler, R. A. Shweder, & G. Herdt (Eds.), Cultural psychology: Essays on comparative human development (pp. 1–43). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Sperber, D. (1996). Explaining culture: A naturalistic approach. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Tapp, J. L., Kelman, H. C., Triandis, H. C., Wrightsman, L., & Coelho, G. (1974). Continuing concerns in cross-cultural ethics: A report. International Journal of Psychology, 9, 231–249.

- Triandis, H. C. (1964). Cultural influences upon cognitive processes. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–48). New York: Academic Press.

- Triandis, H. C. (1989). Self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review, 96, 506–520.

- Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and social behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Triandis, H. C., & Lambert, W. W. (Eds.) (1980). Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Perspectives (Vol. 1). Rockleigh, NJ: Allyn and Bacon.

- Witkin, H. A., & Berry, J. W. (1975). Psychological differentiation in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of CrossCultural Psychology, 6, 4–87.

- van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.