This sample Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) classification system for mental disorders, developed by the American Psychiatric Association and now employed worldwide, has its historical roots in previous systems dating back over several centuries, from the Greek Hippocrates in the fourth-century BC to the nineteenth-century German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin. This research-paper traces the development of the DSM, describing successive changes and improvements over the course of its six editions, as well as its relationship with the other main system, the European-based International Classification of Diseases.

Outline

- Antecedents

- DSM-I (1952)

- DSM-II (1968)

- DSM-III (1980)

- DSM-III-R (1987)

- DSM-IV (1994)

- Categorical Development of the DSM

1. Antecedents

Classification is both the process and the result of arranging individuals into groups formed on the basis of common characteristics. It is important in any science, but it is usually a difficult task that raises a variety of problems for experts to deal with, including mixture (heterogeneity or homogeneity of a group), discrimination (between-group differences), and identification (assignment of an individual to a group).

Historically, the first attempt to put the variety of psychological disorders into some kind of order was made by the Greek physician Hippocrates (4th century BC); he coined the terms phrenesis, mania, and melancholia, which were maintained by Galen in Rome (1st century AD). Much later, during the Renaissance, Barrough (1583) divided mental disorders into mania, melancholia, and dementia. The work was continued in Europe by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in his Anthropologie and by the Frenchman F. Pinel in his Nosologie Philosophique (1789), which divided mental disorders into mania with and without delirium, melancholia, dementia, and idiocy. The Swede, K. Linnaeus, better known for his classifications of plants and animals, also extended his work to the field of the human mind, employing such categories as Ideales (delirium, amentia, mania, melancholia, and vesania), Imaginnarii (hypochondria, phobia, somnambulism, and vertigo), and Patheci (bulimia polydypsia, satyriasis, and erotomania). At the end of the 19th century, the German, Emil Kraepelin—often considered the founder of modern scientific psychiatry—in his Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie [Handbook of Psychiatry] (1899) included a highly influential classification. He aimed to identify groups of patients through symptom clusters that would define different syndromes, and he attributed disorders to four organic roots: heredity, metabolic, endocrine, and brain disease. His categorization laid the bases for systems such as the first official American Psychiatric Association (APA) classification, which included mental disorders by brain traumatism, mental disorders by encephalopathy, mental disorders by drugs, mental disorders by infectious agents, syphilis, arteriosclerosis, epilepsy, schizophrenia, manic–depressive psychosis, psychopathy, psychic reaction, paranoia, oligophrenia, and other cases.

In the 1960s, neo-Kraepelinian psychiatrists called for improvements to the old classification, and men such as Spitzer, Endicott, and Feighner began to prepare the construction of a new American psychiatric classification.

Although the roots of modern American classification are in Europe, the first official classification was a census of mental disorders drawn up in the United States in 1840, with just two categories: idiocy and madness. Another important antecedent of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was the work of the Committee on Statistics of the American Psychiatric Association (1917), led by Dr. T. Salmon, which recorded mental disease statistics from the psychiatric services of hospitals. Its result was the Statistical Manual for the Use of Hospitals for Mental Disease. A few years later, the New York Academy of Medicine organized the National Conference on Disease Nomenclature (1928) to unify the terminology and nosology used by practitioners; its Standard Classified Nomenclature of Diseases (1932; rev. ed., 1934) originally referred only to physical diseases, but a section on Diseases of the Psychobiological Unit was included later, and the 1951 edition was published for use in mental hospitals. All of these classifications owed a debt to Kraepelin’s system.

World War II brought so many diagnostic problems to military psychiatrists that they urged the construction of a Classification of Mental Problems. The psychological nomenclature was introduced in 1944 by the Navy and a year later by the Army. However, the existing Standard Nomenclature (1932) proved inadequate for many situations, and the Armed Forces asked for a revision of the three systems in use. The result was the creation of the DSMs.

In Europe, a parallel movement, that of mental hygiene, held its first meeting in Paris in 1932. A European classification would unify psychiatric nomenclature, with the following categories: congenital mental disorders, endogenous psychosis, reaction psychosis, symptomatic psychosis, encephalopathies, epilepsy, toxicomany, and non-aliened mental disorders. However, this proposal was not well accepted by the mental health community.

Today, the two most well-known categorical classifications of mental disorders are the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the DSM. The ICD, created in Europe, has been promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) since 1900, but its original version included only physical diseases; the DSM, published by the APA since 1952, has always focused on mental disorders. The two classifications attempt to deal with the same behaviors and coincide to a large extent, but there are some important differences.

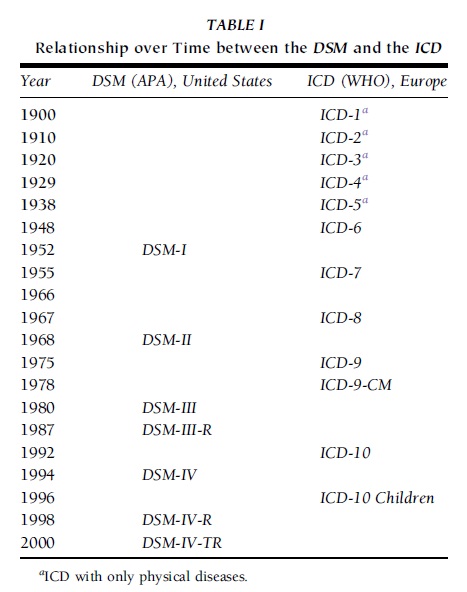

The first ICD versions included only physical disorders (Table I), but the ICD-6 (1948) saw the incorporation of mental diseases, bringing it closer to the DSM-I. The ICD-8 (1967) and DSM-II (1968) also coincided in many aspects, but the APA’s decision to develop the DSM-III generated new tensions. Much of this divergence was resolved through better communication, and the DSM-IV and ICD-10 reestablished the close relationship between the WHO and the APA.

2. DSM-I (1952)

The DSM was first published in 1952 (DSM-I). Influenced by its European antecedents, and by the views of A. Meyer (a biologically oriented psychiatrist) and K. Menninger (who was psychoanalytically oriented), it took into account not only biological but also social and psychological elements, and it offered a multidimensional consideration of disorders. The process of developing the manual involved the collaboration of the National Institute of Mental Health and different psychiatrists and military professionals.

TABLE I Relationship over Time between the DSM and the ICD

TABLE I Relationship over Time between the DSM and the ICD

Its impact was quite limited. Smith and Fonda, in a study using the DSM-I criteria, found interrater agreement to be high for organic psychosis, melancholia, and schizophrenia but quite low in many other categories.

Other studies were also critical. For example, the omission of criteria was criticized by H. J. Eysenck and R. B. Cattell; in their view, common nomenclature in itself would not improve clinical diagnosis, as clinicians would understand different things from the same labels. Furthermore, P. E. Meehl questioned the reliability of clinical judgment, whereas L. Cronbach and Meehl drew attention to the urgent need for accuracy in diagnostic identification.

With the publication of the ICD-7, some of the differences between the WHO and APA classifications were highlighted. The DSM-I categories were also adopted for a computer program designed for assessment tasks (DIAGNO), but this presented some problems of application. The need to improve the system was evident, and it was Endicott, Guze, Klein, Robins, and Winokur who assumed the task of reviewing and improving the manual.

3. DSM-II (1968)

This was published as the American National Glossary to the ICD-8. An APA committee, with the help of some experts, carried out an in-depth revision of its first version. Meyer’s previous influence was drastically reduced, whereas more room was given to psychoanalytical and Kraepelinian ideas in order to improve its acceptance by clinicians. It was based on the medical illness model of different syndromes made up of clinical symptom clusters.

Many unsuccessful attempts were made to coordinate the DSM and ICD systems, but the differences eventually increased, both in diagnoses and in terminology. For instance, the DSM-II had 39 more diagnoses than the ICD-8 10/3, and regarding terminology, terms associated with certain theoretical frameworks (such as ‘‘schizophrenic reaction’’ for schizophrenia) were avoided but others, such as ‘‘neuroses’’ or ‘‘psychophysiological disorders,’’ remained.

The DSM-II has frequently been referred to as ‘‘old wine in a new bottle’’ since the influences of Meyer and Kraepelin were still present but many of the new research perspectives were absent. One year after its publication, Jackson described it as ‘‘a hotchpotch of different bases of classification.’’ However, studies on schizophrenia diagnosis in various countries greatly stimulated the task of revision, and efforts were redoubled to clarify basic diagnostic criteria, paving the way for the construction of the DSM-III.

4. DSM-III (1980)

Criticism of the previous editions had noted the lack of an organizing criterion and the overlapping of categories. Efforts to improve the instrument culminated in the publication of the DSM-III.

A task force chaired by R. Spitzer, with international cooperation and the participation of N. Andreasen, J. Endicott, D. F. Klein, M. Kramer, Th. Millon, H. Pinsker, G. Saslow, and R. Woodruff, prepared the work. New members were added subsequently, and a draft was prepared at the important St. Louis conference in 1976. Collaborators were recruited from many institutions, including the Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, the American Association of Chairmen of Departments of Psychiatry, the American College Health Association, the American Orthopsychiatry Association, and the American Psychological Association. Misunderstandings arose between the American Psychological Association and the American Psychoanalytical Association, but all were eventually solved.

The goals of these teams were (i) to expand the classification, maximizing its utility for the outpatient population; (ii) to differentiate levels of severity and cause within syndromes; (iii) to maintain compatibility with the ICD-9; (iv) to establish diagnostic criteria on empirical bases; and (v) to evaluate concerns and criticisms submitted by professional and patient representatives. Subsequently (1977–1979), drafts were sent to experts and practitioners for study and suggestions before the definitive modifications were made. The major characteristics of the DSM-III are (i) operational or explicit criteria for assigning patients to diagnostic categories and (ii) the implementation of a multiaxial framework.

4.1. Explicit Diagnostic Operational Criteria

Diagnostic criteria make explicit the signs and symptoms required for a diagnosis on the basis of empirically validated rules, and they are not only descriptive but also phenomenological and behavioral. They would permit greater effectiveness and reliability in diagnoses. Also included for each disorder was its description, the usual age at which it begins, mean duration, prognosis, rates by sex, and risk factors. Criteria for Axes I and II are basically the same as the Feighner Criteria, based only on disorder definitions, as in the DSM-I and DSM-II.

Such criteria were used when creating the Research Diagnostic Criteria, which included 23 disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder–manic, schizoaffective disorder–depressed, depressive syndrome superimposed on residual schizophrenia, manic disorder, hypomanic disorder, bipolar with mania, bipolar with hypomania, major depressive disorder, minor depressive disorder, intermittent depressive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, cyclothymic personality, labile personality, Briquet’s disorder, antisocial personality, alcoholism, drug-use disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, phobic disorder, unspecified functional psychosis, and other psychiatric disorders).

An operative description of clinical disorders was included, employed in Axes I and II of the DSM-III to differentiate between syndromes. Unlike those of the biological classifications, DSM-III criteria are polythetic (patients do not need to have all the characteristics in order to be included in a category) and intentional (patient’s characteristics are listed).

4.2. Inclusion of Five Diagnostic Axes

A new feature in the DSM-III was the inclusion of five diagnostic axes in order to obtain greater sensitivity and accuracy in diagnoses and treatments and permit the consideration of psychosocial aspects. The idea of such axes was introduced by Essen, Mo¨ ller, and Wohlfahrt (in Sweden in 1947). They proposed separating the syndromes from all etiological conceptions, creating two principal axes (‘‘phenomenological’’ and ‘‘etiological’’) plus three others (‘‘temporality,’’ ‘‘social functioning,’’ and ‘‘others’’). In 1969, Rutter et al. in the United Kingdom constructed a multiaxial classification system for children (with axes for clinical syndromes, delay of development, mental retardation, medical condition, and psychosocial situation), and other multiaxial systems were proposed in the United Kingdom by Wing in 1970, in Germany by Helmchen in 1975, and in the United States by Strauss. Apart from the DSM-III, the multiaxial formula was applied to the ICD in 1992.

Axes were assigned as follows: Axis I to clinical syndromes; Axis II (with two sections) to child maturational problems and adult personality disorders; Axis III to physically rooted problems; Axis IV to the intensity and severity of psychological stressors; and Axis V to the patient’s level of adaptive functioning in the past year, objectively evaluated. Axes II, IV, and V link the syndromes with environmental determinants and reflect a shift toward more psychological conceptions.

DSM-III constitutes an authentic work of description on psychopathology (including differential diagnosis, etiology, treatment, prognosis, and management). The DSM-III, although atheoretical in principle, maintained a biological interpretation of the field. Although praised for its achievements, it was also criticized for including inessential characteristics of disorders and for employing too many diagnostic categories (265); psychoanalysts also criticized the lack of an axis that took into account defense mechanisms and ego functions, and they complained that the replacement of the term neuroses by anxiety disorders situated them at a greater distance.

In sum, the DSM-III represents a key stage in the evolution of the DSM classification. This change was both quantitative (from 104 syndromes to 395, and from 132 pages to 500) and qualitative. Since 1980, with the adoption of the axes system, the corpus of categories has remained practically constant. Moreover, DSM-III made important progress in relation to aspects such as reliability, intracategory coherence and differentiation, validity, and behavioral data. It also favored the construction of new assessment instruments based on its criteria (self-rating questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and so on). Despite all these innovations and improvements, further revision was necessary, and this arrived in the form of the DSM-III-R.

5. DSM-III-R (1987)

This appeared in 1987 as the final result of revisions carried out by a work group headed by Spitzer. Innovations included the reorganization of categories; some improvements in Axes IV (on psychosocial stress) and V [inclusion of the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning (GARF) scale]; and the incorporation of aspects related to drug abuse, homosexuality (now included in unspecified sexual disorders), and hyperactivity. Classification of affective disorders was reorganized. This version had a dramatic impact worldwide and became more commonly used than the ICD, even in Europe.

6. DSM-IV (1994)

A task force led by Allen Frances working with experts and scientific groups from all over the world prepared this version. The goal was to improve its cultural sensitivity and to improve compatibility with the ICD.

Features of the new instrument included (i) brevity of criteria set, (ii) clarity of language, (iii) explicit statements of its constructs, (iv) it was based on upto-date empirical data, and (v) better coordination with the ICD-10. The DSM-IV also presented a series of changes with respect to its predecessor. Categories such as organic mental disorders disappeared, whereas others such as eating disorders, delirium, dementia, and amnesic and other cognitive disorders, and some severe developmental disorders (Rett’s syndrome and Asperger’s syndrome), were incorporated; the categories of child and sexual disorders were restructured.

In the multiaxial system, the changes occurred in Axis IV, which includes more stress-generating events, and Axis V, in which other scales were added for determining level of adaptation—the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale and the GARF scale.

Criticism of the DSM-IV has not been lacking, especially with regard to its focus on consensus more than on data. However (and despite claims that there would never be a DSM-V), remodeling of the DSM-IV is currently in progress.

7. Categorical Development Of The DSM

7.1. Important Changes

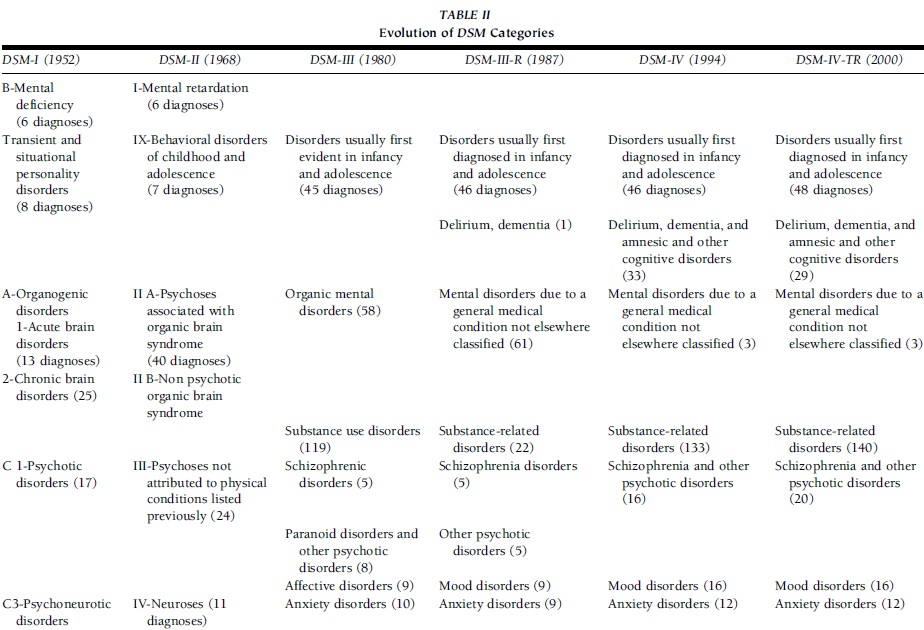

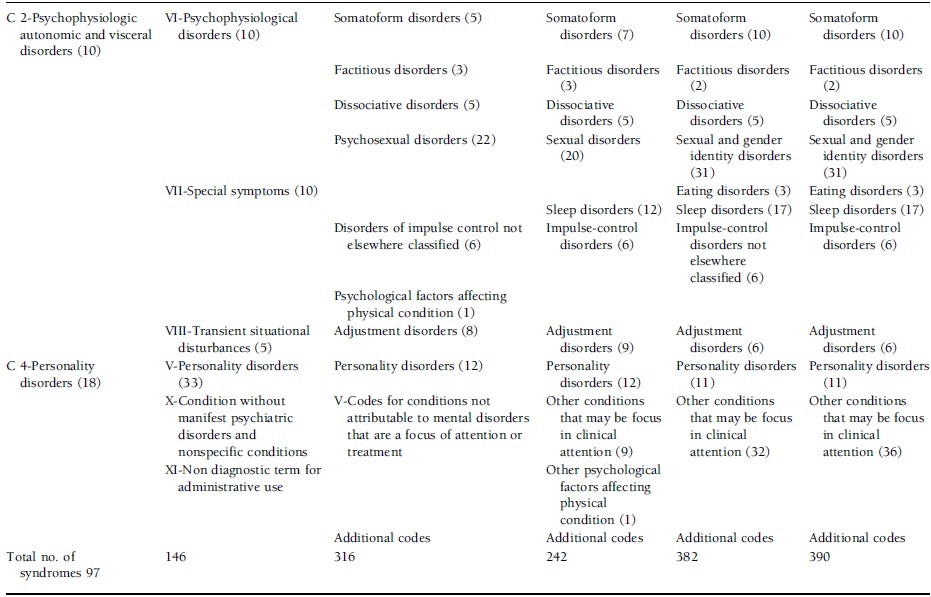

Over time, the DSM categories have undergone significant changes. Whereas in 1952 there were two main categories, in 2000 there were 17. This increasing complexity is even more evident in the case of subcategories (Table II).

Each diagnostic category is identified by a numerical code. The current DSM codes the different disorders with its own code and also with that of the ICD, making it possible to compare and contrast diagnoses made with these two different categorical systems, thus facilitating communication between them.

7.2. Critical Positions

The DSM classification system has attracted criticism from various theoretical points of view. Those from the antipsychiatry current have always been against the use of classifications in psychiatry since they consider labeling a dangerous procedure. Another notable critic was Eysenck, who spoke of the fundamental weakness of any scheme ‘‘based on democratic voting procedures rather than on scientific evidence.’’

Further criticisms of the DSM refer to (i) the cultural biases of all classification systems; (ii) its extreme individualism—only individual diagnosis is taken into account; (iii) the influence on it of old-fashioned medical classifications, despite modern developments in psychology and psychiatry; and (iv) the ‘‘softness’’ of the categories, which are based more on description than explanation, despite the crucial importance of the latter. However, despite such criticisms, categorical classifications have made possible comparisons and inferences that have helped to advance clinical knowledge. They may have their imperfections, but they have made an enormous contribution to diagnostic reliability and to understanding among mental health professionals. They have also helped to promote the creation of more homogeneous and accurate assessment instruments that will constitute the source of future progress in the field.

TABLE II Evolution of DSM Categories

TABLE II Evolution of DSM Categories

References:

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 529, 281–203.

- Eron, L. D. (1966). Classification of behavior disorders. Chicago: Aldine–Atherton.

- Feighner, J. P., Robins, E., Guze, S. B., Woodruff, R. A., Winokur, G., & Munoz, R. (1972). Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Archives of General Psychiatry, 26, 57–63.

- Haynes, S. N., & O’Brien, W. H. (1988). The Gordian knot of DSM-III use: Interacting principles of behavioral classification and complex causal models. Behavioral Assessment,10, 95–105.

- Millon, Th. (1996). The DSM-III: Some historical and substantive reflections. In Th. Millon (Ed.), Personality and psychopathology. New York: Wiley.

- Schmith, H. O., & Fonda, C. (1952). The reliability of psychiatry diagnosis. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,52, 262–267.

- Spitzer, R. L., Endicott, J., & Robins, E. (1975). Research diagnostic criteria (RDC). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute.

- Spitzer, R. L., Gibbson, M., Skoldol, A. E., Williams, J., & First, M. B. (1994). DSM-IV Casebook: A learning comparison to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Spitzer, R. L., & Willson, P. T. (1975). Nosology and the official psychiatry nomenclature. In A. M. Freeman, H. I. Kaplan, & B. J. Sadock (Eds.), Compressive textbook of psychiatry (Vol. 2). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- Szasz, T. (1966). The psychiatry classification of behavior: A strategy of personal constraint. In L. D. Eron (Ed.), The classification of behavior disorders (pp. 123–170). Chicago: Aldine.

- Widiger, T. A., Frances, A. J., Pincus, H. A., First, M. B., Ross, R., & Davis, W. (1994). DSM-IV sourcebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.