This sample Disabilities Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Following a holistic perspective, this chapter will provide the reader a deeper understanding of what a disability is and how individuals are affected by disabilities. In this time of political correctness, this chapter will also provide the reader with insight into the social etiquette one should consider when discussing issues pertaining to individuals with disabilities and when in the presence of individuals with disabilities.

Why is it important to understand and study disability as a separate topic from other areas of psychology? The answer lies in the variety of unique life experiences held by individuals with disabilities and the role disability plays in different cultures. Current estimates indicate that approximately 54 million Americans have a disability, making individuals with disabilities one of the largest minority groups in the United States. Other estimates suggest that one out of eight individuals will acquire an acute or chronic disability within their lifetime. The specific concerns of individuals with disabilities are so great that the United States government created legislative bodies and mandates to protect the rights of these individuals.

Since the mid-20th century, research and literature have been inundated by numerous theories of disability and its impact on individuals. Because it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss all theories, I will provide an overview of the two theories that are central to all disability theories—the medical model and the rehabilitation model.

To understand the concept of disability, we must first provide an operational definition. The general term disability is a broad term that encompasses the multitude of existing mental disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and any physical condition listed in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Although this general explanation of disability appears to be simple, the concept of disability is much more complex.

Prior to the 1960s, professionals believed disability was a medical term synonymous with the term disease. Thus, medical professionals followed the medical model in treating individuals with disabilities; they viewed individuals as the patient and the disability as a treatable disease. Doctors were the experts on the disease and its treatment; patients had little or no input over treatment options. In many cases, patients were subjected to experimental treatments that produced more harm than good. Patients with disabilities, especially cognitive disabilities, were subject to such experimental treatments as insulin-coma therapy, trepanation, rotational therapy, hydrotherapy, mesmerism, malaria therapy, chemically induced seizures, hysteria therapy, phrenology, and even lobotomy.

Although many medical professionals still follow the medical model in the treatment of common diseases and illnesses, the majority of all medical and health professionals follow the rehabilitation model when treating individuals with disabilities. The key term here is rehabilitation, which literally means “to rehabilitate” or “to make new again.” Although it is not always possible to make an individual with a disability “new again,” health professionals try to help individuals with disabilities recover, minimize limitations, and maximize strengths and abilities. The rehabilitation model stresses that the individuals own the disability and have control over maximizing their abilities, whereas the medical model assumes that the disability controls the individual and the disability is preventing the maximization of abilities. The rehabilitation model takes a holistic perspective when treating individuals with disabilities, incorporating and promoting physical, mental, social, and even spiritual healing. The rehabilitation model also emphasizes the involvement of individuals with a disability in choosing their treatments and in the development of their rehabilitation plan. In short, under this model disability professionals view patients as experts of their own experiences of the disability.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has adapted its definition of disability from the rehabilitation model, indicating that a disability is not so much a medical problem as it is a socially contrived problem. The WHO stresses that society has created an environment for individuals with disabilities filled with both physical and attitudinal barriers. The negative affects of a disability are not due to an individual’s condition but rather to environmental factors such as the lack of social integration, social action, individual and collective responsibility, environmental manipulation, attitude, human rights, politics, and overall social change. Within the WHO’s definition of disability, environmental factors assume a role equal to that of personal factors such as sex, ethnicity, and so on in how a disability affects an individual’s overall life experiences. Disability activists and legislators in the United States incorporated the WHO’s definition into the language of the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1974. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act defines “disability” as “(a) a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual; (b) a record of such an impairment; or (c) being regarded as having such an impairment.”

It is important to distinguish between the term disability and another term that some people have used as an improper synonym for disability, handicap or handicapped. The term handicap means a condition (usually environmental) that prohibits an individual from accessing or participating in an activity. An individual with a disability is not handicapped unless society has placed a barrier to accessing or participating in an activity. For individuals with disabilities, the disability did not create a handicapping condition, society did. The individual’s disability just makes it harder to overcome or adapt to the handicapping condition. For example, prior to the 1970s, curb cuts did not exist. Individuals with mobility impairments and who were restricted to using wheelchairs often were unable to move about in the community because they were unable to wheel up and over curbs; thus, the curbs created a handicapping condition for these individuals. Today, these same individuals are able to participate in the community because curb cuts have eliminated the handicapping condition.

Knowing this distinction between the terms disability and handicap leads us to the most important lesson in disability etiquette. The first rule of disability etiquette is to always put the individual first; it is never proper to refer to someone as handicapped or disabled. Because the term handicap refers to an environmental condition, it is illogical to assume that an individual is handicapped unless you are referring to the specific handicapping condition that is preventing the individual from accessing or participating in an activity. In practice, it is also improper to refer to someone as disabled. As disabilities tend to only impact certain aspects of an individual and range in severity, it is illogical once again to assume that the disability has consumed the entire individual. Therefore, it is only proper to refer to someone as an individual with a disability, or people with disabilities if referring to a group.

Understanding the first rule in disability etiquette lends itself to the second rule of disability etiquette. Professionals, nonprofessionals, and other members of society should view individuals with disabilities as ordinary people, just like everyone else. Individuals with disabilities have lives worth living, stories worth telling, and relationships worth building. Due to some disabilities not being visibly noticeable, many individuals with a disability are not recognized as having a disability. There is an innate fear of the unknown within all humans, and only knowledge can extinguish this fear. It is recommended that anyone who will be working with individuals with disabilities, or who has family or friends with disabilities, not let this fear consume them. Most individuals with disabilities are more than willing to share their life experiences and provide a better understanding of how their disability affects them.

Disability Prevalence

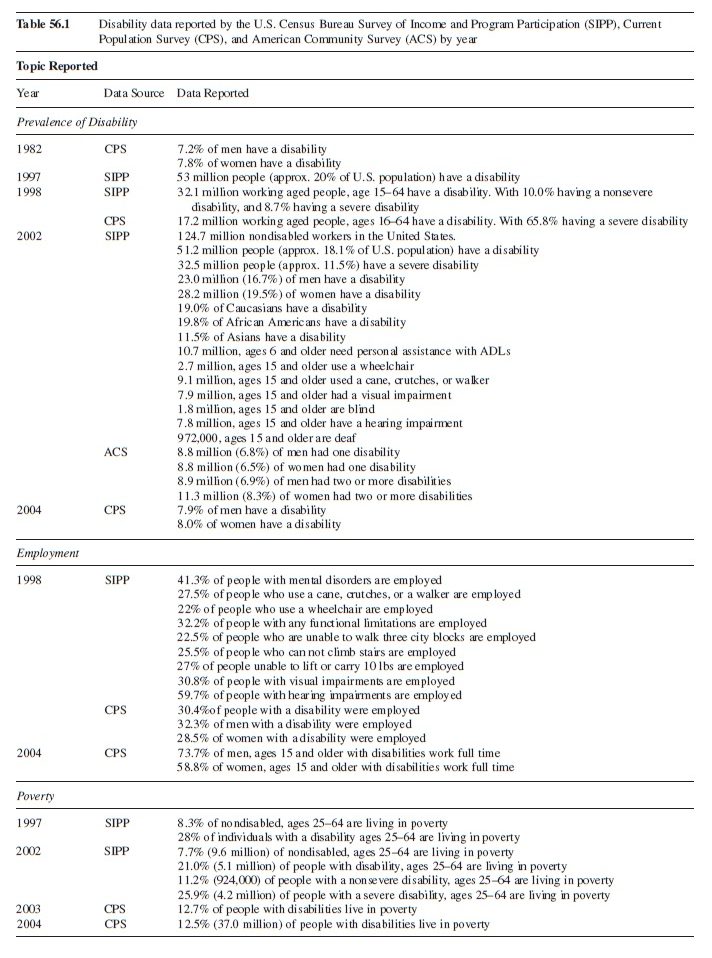

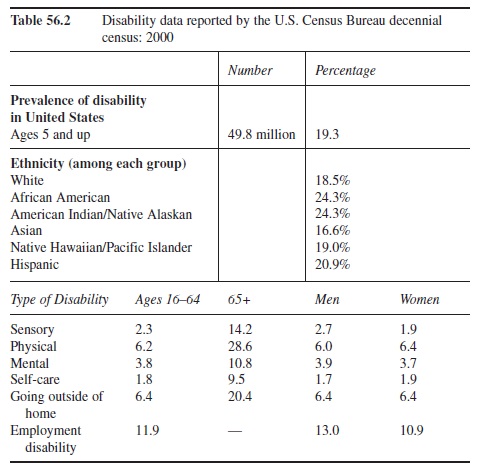

Currently there is no single data source reflecting the population characteristics of individuals with disabilities living in the United States. Therefore, it is necessary to examine multiple data sources to acquire a general understanding of the topic. Stern (2003) cautions that because the current data sources are not specifically directed to measuring disability and related topics, researchers should be wary of the reliability and validity of the estimates provided. Table 56.1 and Table 56.2 display the most current available data on individuals with disabilities. As can be seen from these two tables, each of the four U.S. survey instruments has provided inconsistent and inexact data. For a more in-depth look at disability statistics, readers should visit the U.S. Bureau of Census and Cornell Universities Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Disability Demographics and Statistics (StatRRTC) Web sites.

Table 56.1 Disability data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), Current Population Survey (CPS), and American Community Survey (ACS) by year

Table 56.2 Disability data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau census: 2000

Table 56.2 Disability data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau census: 2000

Historical Overview

Due to the fragile nature of the human body, it is not hard to believe that injuries and disabilities have existed since the dawn of mankind. What is surprising, though, is how individuals with disabilities have been treated by the nondisabled community. Although it is impossible to discuss the treatment of individuals with disabilities within each of the different cultures and time periods, the generalization that individuals with disabilities have been treated as less than human throughout history is accurate. For example, it was not uncommon for children born with developmental disabilities to be killed after birth. Nor was it uncommon for elders who had acquired severe disabilities to face the same fate. Individuals with disabilities were viewed as burdens and hindrances on society and societal resources, making their death much more acceptable.

Fortunately, though, there have been those who have tried to help individuals with disabilities live in their society. Dorothea Dix is one of the most noteworthy individuals in this group. She spent much of her life traveling throughout the United States in the late 1700s and early 1800s advocating for humane treatment of individuals with disabilities, as well as the poor and imprisoned; her work ultimately grew into the disability rights movement in the United States. One of Dix’s biggest accomplishments for individuals with disabilities occurred in 1817, with the founding of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut—the first school for children with disabilities. As the years went by, leading up to the late 20th century, many small obstacles had been overcome by individuals with disabilities. Unfortunately, those obstacles/barriers were not removed for all individuals with disabilities.

Similar to women and other minorities, individuals with disabilities have struggled throughout history for equality. During the turn of the 20th century, many lawmakers throughout the United States deemed it morally and ethically necessary to protect workers who became injured or disabled while on the job, and by 1919, 43 states had Workers’ Compensation laws in place. Although the laws in each of these 43 states were written differently, they provided protection for both men and women who became injured or disabled. Unfortunately, no legislation or laws contained any clause prohibiting discrimination against workers with disabilities or provided equal pay for workers with disabilities.

As World War I came to an end and soldiers with disabilities returned home to the United States, Congress felt obligated to pass the Smith-Sears Veterans Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1918, the first vocational rehabilitation legislation providing assistance to veterans with disabilities. Two years later, Congress passed the Fess-Smith Civilians Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1920, the first vocational rehabilitation legislation providing assistance to civilians with disabilities. Although these two acts were monumental at the time, neither one was concerned about discrimination against veterans or civilians with disabilities. Instead, both pieces of legislation made funds available to individuals with disabilities for rehabilitation services, which did not include funds for disability advocacy. Through the mid-20th century, legislators continued to provide support for individuals with disabilities in terms of vocational and rehabilitation services, including funding under the 1935 Social Securities Act to the blind and children with disabilities. But again, individuals with disabilities were not given the civil liberties afforded to individuals without disabilities living in the United States.

Although many advocates had fought for the rights of individuals with disabilities, it wasn’t until the 1960s that the disability rights movement began to take form. Switzer (2003) identified five social and political events taking place that gave rise to the disability rights movement, the most important being the civil rights movement, which took place during the 1950s and 1960s. Although individuals with disabilities were not considered a minority at the time, society began recognizing the harm that discrimination could do and the need for equality.

During the 1960s, the disability rights movement also found a strong political ally in Ralph Nader, who helped the movement’s voices be heard in Congress. Nader believed that individuals with disabilities should be viewed as consumers and taxpayers in society, not as a hindrance. He stated that such consumerism would help society grow and prosper, creating supply and demand for goods. As consumers, these individuals should have the choice over what goods and services they were to receive (a big component to later legislation development).

While Nader was pushing the idea of consumerism, a paradigm shift was occurring in society, moving from the medical and pure economic model to the rehabilitation model. The shift to the rehabilitation model was driven by the push for consumerism. Individuals with disabilities wanted control over their life, including the “treatment” of their disability. Without legislation to provide and enforce these rights to individuals with disabilities, however, they were denied access and participation in the available services and activities.

During the late 1960s, the disability rights movement obtained yet another new ally. The self-help movement also began to turn away from the medical model and traditional medical treatments. Talk therapy became the desired treatment for mental or psychological issues, and herbal or natural remedies became popular for medical ailments. The self-help and disability rights movement provided individuals with choices, and the resulting demedicalization and deinstitutionalization occurred because of the need for “choice.” At this time the disability rights movement developed a goal; leaders of the movement pushed for legislation that would allow individuals with disabilities to choose their services and access the services to which they were entitled.

After much debate in Congress and being vetoed twice by President Nixon, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was enacted; it was a major victory for people with disabilities. Under Title V: Rights and Advocacy, Section 504.a.— Nondiscrimination under Federal Grants and Programs, individuals with disabilities could not be discriminated against or denied access to programs receiving any form of federal moneys. The Rehabilitation Act enabled individuals with disabilities to become true consumers of goods and services. The Rehabilitation Act also mandated that individuals with disabilities play a prominent role in the development of their rehabilitation plan and have the ability to decide their vocational future.

Following passage of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, the Architectural Barrier Act, the Air Carrier Access Act, and the Urban Mass Transportation Act. These pieces of legislation provided guidelines that allowed individuals with disabilities to have full, barrier-free access to society. Unfortunately, the Rehabilitation Act was not comparable to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in that it provided only that individuals with disabilities would not be prevented from receiving services or participating in activities. It did not stop society from carrying out discriminatory practices against individuals with disabilities.

Although the disability rights movement finally saw victory during the 1970s, a new administration with a much different view of the governments role in society was about to take over. During the 1980s, the Reagan administration believed in diminishing governmental control and putting more control in the hands of the states; thus, the administration attempted to dismantle the Rehabilitation Act and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. President Reagan believed that there were too many federal regulations on businesses and state agencies that were hindering them from providing the best goods and services. Fortunately, the administration abandoned the crusade after much lobbying and letter writing from people with disabilities. However, the administration decided to reduce Social Security benefits, which effectively hurt many thousands of individuals with disabilities.

Although the Reagan administration was a tenacious opponent of the disability rights movement, the movement found a powerful ally in the most unexpected place. Under President Reagan, Vice President George H. W. Bush was placed in charge of working with the disability groups. Listening to their concerns, Vice President Bush sided with individuals with disabilities during that time and gained their support for his presidency. After President Reagan left office, individuals with disabilities pushed for having the full rights of any other United States citizen. Although multiple disability groups had joined together in support of disability rights, the overall effort was loosely structured and did not receive much attention from the public or the media. Protests were small but effective in getting messages across, and movement leaders such as Justin Dart spent time and money traveling the country to give speeches on disability rights.

On July 26, 1990 individuals with disabilities gained full citizenship in the United States as President George H. W. Bush signed into law the Americans With Disabilities Act. According to Tony Coehlo and other writers of the ADA, the goal of the ADA was to help individuals with disabilities become independent and self-sufficient. The ADA accomplished this goal by outlawing the use of discriminatory practices against individuals with disabilities. Unlike the Rehabilitation Act, the ADA did change the view of society. Nearly every place of business and employment had to now recognize and work with individuals with disabilities in some manner.

One of the most important similarities between the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the ADA of 1990 was the notion of reasonable accommodations. Employers and businesses are required to make the necessary changes to a job, the work environment, or business setting so that an individual with a disability will have full, barrier-free access. However, the ADA provides protection to the businesses and employers by adding that any accommodation(s) provided had to be “reasonable” and must not cause “undue hardship” on the business or change the business itself.

Since the ADA was signed into law in 1990, proponents of the ADA have stated the only true downfall of the act is that it has been difficult to enforce. According to Switzer (2003), there are approximately 39 different government agencies with the responsibility of overseeing disability-related programs. Of these agencies, only the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is charged with enforcement of discrimination law and making sure discrimination is not occurring within the employment setting either pre- or postoffer. The EEOC is also the only agency that has been given the right to pursue employment discrimination charges against employers even when the individual(s) discriminated against do(es) not want to pursue legal action. All other situations of discrimination against individuals with disabilities are divided among the other 38 agencies. Many times, because of mass confusion concerning who should enforce a certain aspect, the issue is often ignored or the individual with a complaint is left to track down who is responsible for enforcement.

Rehabilitation Profession

An important perspective that has increasingly characterized the helping field is the “holistic” approach to viewing and meeting the needs of individuals with disabilities. Thus, practitioners using this approach look at the mental, physical, and spiritual aspects of individuals with disabilities to provide or coordinate appropriate services (Goodwin, 1986). In previous years, no one profession has had a uniquely holistic approach to helping an individual. Instead, professionals in the medical field or allied health professions focused primarily on physical impairments, whereas psychologists and psychiatrists focused primarily on mental and emotional health. It was the responsibility of individuals in need of help to find and acquire the necessary treatment(s) best suited for their condition (Goodwin, 1982). For many individuals, this was a daunting task because they suffered from multiple disabilities and were in need of not only medical care but also psychological care, social services, or even assistive technology.

The advent of the rehabilitation counseling professional increased the availability of coordination across the entire continuum of services. Rehabilitation counseling not only removed the responsibility from the individual with a dis-ability but also helped reduce gaps or fragmentation within the rehabilitation process.

Under federal guidelines from the U.S. Department of Education’s Rehabilitation Services Administration, every state is required to have state rehabilitation agencies in place to offer rehabilitation services to individuals with disabilities. Although each state agency must follow a set of general federal guidelines for servicing individuals with disabilities, it is left up to each state to determine how to efficiently service those individuals. Although each state rehabilitation agency will have an official name, it is not uncommon for the public to refer to these agencies as state vocational rehabilitation agencies, or state VR services. The term vocational is referring to the primary objective of the rehabilitation services agency to provide employment related services to help the individual with a disability become employed in the community.

The rehabilitation counselor is typically employed in a rehabilitation agency. Rehabilitation counselors are required to meet certain qualifications; these include being a certified rehabilitation counselor (C.R.C.) and, in most cases, completing a master’s degree. Many rehabilitation counselors also have additional certifications in vocational evaluation, career assessment, and work adjustment. It is also not uncommon for rehabilitation counselors to be trained therapists, holding a licensed professional counselor (LPC) certification, social work (MSW) certification, or marriage and family therapist (MFT) certification.

Implications Of Disability

Overview

Although there is a vast amount of research and literature on the topic of disability, it is important to highlight some of the more general aspects of how a disability can impact an individual. However, because of the uniqueness of individual disabilities, you should use caution and not over generalize. For example, the majority of research and literature on disability prior to the 1970s focused on Caucasian males with a disability. Women and other minority groups were excluded from studies, although researchers tried to generalize their findings to these individuals. Similarly, studies that have specifically been conducted on individuals with disabilities have categorized disabilities into broad groups such as learning disabilities, cognitive disabilities, physical disabilities, and so on and have over generalized to the populations of interest. Therefore, the following will not be a synthesis of past research, but rather a brief explanation of important variables that must be taken into account when studying disability.

Disability, Gender, and Ethnicity

Although the ADA protects the rights of all individuals with disabilities, currently there is no legislation that addresses the specific concerns of women with disabilities or other minorities with disabilities. Schur (2003) acerbically describes women with disabilities as having a “double handicap” due to society’s boorish attitude and lack of empathy toward women, especially women with disabilities. Although the term handicap is antiquated, Schur believes it is an apt one to describe women with disabilities; society’s attitudes and prejudicial actions toward these women are hindering their efforts to participate fully in society. Schur states that women with disabilities have lower employment and income levels than men with disabilities, as well as lower levels of political participation and internal political efficacy. Gerschick (2000) contends that society must begin to identify women with disabilities as having their own identity and unique experiences in life. For these women, Gerschick explains that there is a three-way interaction between sex, society, and disability; until researchers and sociologists determine the true nature of this three-way interaction, women with disabilities will continue to be marginalized.

Similar to women with disabilities, minorities with disabilities are presented with increased challenges while living with a disability. Minorities not only have to face the still prevalent prejudices and discrimination of society against minorities but also must contend with how having a disability impacts their role in their family and in their culture. Professionals working with minorities with disabilities should take extra caution not to offend individuals with a disability or their family and cultural values. Accordingly, professionals should take additional time during their initial visits/consultations with minorities with disabilities to acquire as much background information as possible, as well as an in-depth understanding of their family and cultural values.

Disability and Career

Both men and women in our society are expected to contribute to the success of society by having a job and being able to pay taxes. Employment research has indicated that employment has been found to contribute to individuals not only monetarily but also physically, psychologically, socially, and even spiritually. Accordingly, employment of any form increases an individual’s personal satisfaction and overall quality of life. Employment helps individuals meet their basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter, as well as pay for miscellaneous life needs and desires. Unfortunately, many individuals with disabilities have found that meeting their basic needs is a challenge, and those individuals are demanding better pay and better employment opportunities.

Over the past 20 years many researchers have defined career in one of two basic ways: (a) as a vocational choice that is well suited to the individual based on personal factors such as interests, expectations, needs and desires, or (b) as a vocational choice that is deemed “worthy” by the individual based on personal factors such as feelings of connectedness, participation in society, personal worth or significance, and a sense of calling or passion. The majority of rehabilitation professionals working with individuals with disabilities have merged these two ideas to encompass the whole persona.

The term career is the true backbone of the rehabilitation field. Unfortunately, due to increasingly large caseloads assumed by rehabilitation counselors, the term career has become a euphoric metaphor, replaced by the ever-demeaning term “closure.” Individuals with disabilities are shuffled through the rehabilitation process like cars on an assembly line, with no intrinsic value given and little attention paid to standard federal safety regulations. Although the system varies from state to state, the outcomes are much too familiar. Individuals with disabilities are lucky to find themselves in a job of interest with accommodations to it their disability and competitive wages.

Employment experts have stated that today’s workers are expected to handle more pressure, unpredictable change, use of technology, and interpersonal communication in the workplace than in previous decades. Likewise, individuals with disabilities must contend with these same environmental pressures, but they will require support to be able to achieve success equal to that of the nondisabled in the workplace.

In the work environment, individuals with disabilities tend to have more difficulty in situations requiring multiple or delayed instructions and the managing of criticism. Many times, these work situations involve interactions with coworkers or supervisors. Other relevant social skills found to be necessary on the job included nonwork related conversations, interacting effectively during breaks, and a sense of humor. Individuals with moderate to severe disabilities tend to have additional difficulty in a number of other work-related areas, including grooming and hygiene, handling new situations, producing inadequate quality work, lack of confidence, fear of punishment, and meeting deadlines. Other factors that tend to impact individuals with disabilities more than individuals without disabilities include self-defeating beliefs and thoughts, nonproductive emotions, and maladaptive behaviors such as impulsivity, dependence, and social immaturity.

For professionals who wish to help individuals with disabilities acquire and maintain employment, this can be a daunting task, but there are numerous resources available to accomplish it. It is important to point out that one of the best ways to help an individual with a disability acquire and maintain employment is to refer to some of the numerous career theories to help guide the process. One should be cautious when reviewing traditional career theories, though, because it is apparent that many of the theories were developed and based on unemployed, nondisabled individuals who needed to return to work. On the other hand, there is one theory that can easily be applied to individuals with disabilities.

The social cognitive career theory (SCCT), which was primarily influenced by Albert Bandura and his social cognitive theory, can be adapted for use with individuals with disabilities. In their model, Lent, Brown and Hackett (2002) explain that “a complex array of factors such as culture, gender, genetic endowment, sociostructural considerations, and disability or health status operate in tandem with people’s cognitions, affecting the nature and range of their career possibilities” (p. 256). Similar to the cognitive-behavioral model, the SCCT builds on the fact that individuals experience life differently, primarily because they are influenced by external stimuli differently. Even though two individuals may experience the same or similar external stimuli, their thoughts related to the event will be different, thus giving each individual a different perceived experience. For people with disabilities, this is a very important aspect of the model because many of these individuals face many negative external stimuli, such as discrimination or prejudice; if these individuals experience these events as “negative,” their experience will be different from that of an individual who perceives the event as “positive.” The SCCT employs the understanding of the interaction between learning experiences, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations to help individuals successfully proceed through the career process.

Disability and Education

One of the key predictors of employment success for individuals with and without disabilities over the years has been educational level attained. Increased levels of education are correlated highly with income, job satisfaction, and job retention. Unfortunately, acquiring higher levels of education is not always easy for individuals with disabilities. In the past decade, college students with disabilities have received increased attention. Research has focused on the effects of cognitive and affective variables on college performance, faculty and advisors’ willingness to accommodate college students with disabilities, and life experiences of college students with disabilities.

The National Council on Disability 2004 publication, Improving Educational Outcomes for Students with Disabilities, indicated exactly how important increased levels of education are

In 1996, U.S. Census Bureau statistics indicated labor force participation rates at 75 percent for people without a high school diploma, 85 percent for those with a diploma, 88 percent for people with some post-secondary education, and 90 percent for those with at least four years of college. By contrast, only 16 percent of people with a disability and without a high school diploma currently participate in today’s labor force. However, this participation doubles to 30 percent for those who have completed high school, triples to 45 percent for those with some post-secondary education and climbs to 50 percent for adults with disabilities and at least four years of college. (p. 53)

The report continues by stating that students with disabilities lack the necessary self-advocacy skills to successfully navigate the world of work, and those postsecondary institutions need to make a greater effort to help these students acquire those necessary skills.

According to the U.S. Department of Education (2002), there are approximately 1,669,000 students with disabilities at the postsecondary educational setting. Of these students, 29.4 percent have an orthopedic or mobility impairment, 17.1 percent have a mental illness, 15.1 percent have a systemic illness or impairment, 11.9 percent have a visual or hearing impairment, and 11.4 percent have learning disabilities or attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Although Congress has passed legislation mandating transition services for students with disabilities who go from high school to post-high-school, there is no such legislative mandate for services for the transition from postsecondary institutions to adult life and employment.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) amendments of 1997 [34 C.F.R. 300.345(b)], as well as Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act amendments of 1992 [Senate Rep. No. 102-357 at p. 33], emphasize the importance and need for transition services. Transition services are “designed within an outcome-oriented process, that promotes movement from school to post-school activities, including postsecondary education, vocational training, integrated employment (including supported employment), continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living, or community participation” (34 C.F.R Part 300.29, 1997). Although this mandate appears straightforward, there is a loophole that affects individuals with disabilities. If persons with a disability are transitioned to postsecondary education, there are no mandates stating that they are eligible to receive or are required to be provided with transition services from postsecondary school to “integrated employment (including supported employment), continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living, or community participation.” By choosing to further their education, students with a disability give up employment-based services and must find these services on their own upon graduating from the postsecondary institute.

For years researchers have attempted to understand why students with disabilities have such difficulty acquiring postsecondary education. Dalke and Schmitt (1987) theorized that it was due to the transition process that takes place from high school to the postsecondary educational setting. They point out that in the high school setting, students with disabilities are identified more readily by the teachers and school faculty and are given direct access to special education or support services; thus, the support is structured and proactive. In contrast, at the postsecondary level, students with disabilities must seek services themselves, and many institutions do not make students with disabilities aware of such support services. The support services are not structured and are passive in nature.

Summary

Although this chapter has provided a brief overview of the importance of studying disability as a topic, highlighted some of the historical context behind disability, and given insight into the field of disability, this information only begins to scratch the surface of the existing body of knowledge. Even though individuals have acquired disabilities since the beginning of mankind, disability and its impact on an individual as a field of research is currently in its infancy. Each day, researchers and scientists from all over the world are developing new ways to reduce the impact of an illness or impairment on an individual, as well as to prevent illness and impairments. Nevertheless, with an aging population and mankind’s disregard for physical, psychiatric, and spiritual well-being, individuals will continue to acquire disabilities. As such, it is up to those individuals in the health professions to help individuals with disabilities adapt and recover, minimize limitations, maximize strengths and abilities, and return to a state of being which provides the individual with the highest overall quality of life possible.

References:

- Albrecht, G. L., Seelman, K. D., & Bury, M. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of disability studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Public Law 101-336, 42 U.S.C. Section 12101 et seq.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Rev. ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Dalke, C., & Schmitt, S. (1987). Meeting the transition needs of college-bound students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 20(3), 176-180.

- Featherstone, H. (1980). A difference in the family: Living with a disabled child. New York: Penguin Books.

- Gerschick, T. J. (2000). Toward a theory of disability and gender. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 25(4), 1263-1268.

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York: Doubleday.

- Goodwin, L. R., Jr. (1982). A letter in support of rehabilitation counselor licensure. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 13, 32-36.

- Goodwin, L. R., Jr. (1986). A holistic perspective for the provision of rehabilitation counseling services. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 17(2), 25-36.

- Hermann, D. H. (1997). Mental health and disability law in a nutshell. Eagan, MN: West Publishing Co.

- Isaacson, L. E., & Brown, D. (2000). Career information, career counseling, and career development. Needham Heights, MA: Pearson Education Company.

- Lightner, D. L. (1999). Asylum, prison, and poorhouse: The writings and reform work of Dorothea Dix in Illinois. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Public Law 93-112, 29 U.S.C. 706(8), 794, 794a; Amended, 29 U.S.C. 701 et seq. (1992).

- Rubin, S. E., & Roessler, R. T. (2001). Foundations of the vocational rehabilitation process (5th ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

- Schur, L. (2003). Contending with the ‘double handicap’: political activism among women with disabilities. Women & Politics, 25(1), 31-62.

- Sitton, S. (1999). Life at the Texas state lunatic asylum, 18571997. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Stern, S. M. (2003). Counting people with disabilities: How survey methodology influences estimates in Census 2000 and the Census 2000 supplementary survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, HHES Division.

- Switzer, J. V. (2003). Disability rights: American disability policy and the fight for equality. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Geneva: Author.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.