This sample Downsizing and Outplacement Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Employment downsizing is synonymous with layoffs, but it differs from organizational decline. Its extent and scope are global, and it is an ongoing feature of many organizations. Downsizing has led to a redefinition of the concept of loyalty and has led organizations to think in terms of 3to 5-year relationships with employees. Evidence indicates that downsizing does not lead to better long-term performance of organizations, but that it may have negative effects on victims and survivors, particularly if they perceive procedural injustice in the process. Outplacement, which provides counseling for those who have lost jobs as well as assistance in job search, can help to speed the reemployment and readjustment process.

Outline

- Downsizing Defined

- Mergers, Acquisitions, and the Demise of Loyalty

- Corporate Financial Performance before and after Downsizing

- Effects of Downsizing on Knowledge-Based Organizations

- The Psychological Impact of Downsizing on Victims and Survivors

- Outplacement: Easing the Career Transition Process

1. Downsizing Defined

In everyday conversation, the term ‘‘downsizing’’ is often used as a synonym for ‘‘layoffs’’ of employees from their jobs. Downsizing is commonly the result of a broader process of organizational restructuring that refers to planned changes in a firm’s organizational structure that affect its use of people. Such restructuring often results in workforce reductions that may be accomplished through mechanisms such as attrition, early retirements, voluntary severance agreements, and layoffs. Layoffs are a form of downsizing, but it is important to note that downsizing is a broad term that may include any number of combinations of reductions in a firm’s use of assets—financial, physical, human, and information assets. Therefore, when referring to reductions in the numbers of people in an organization, it is appropriate to use the term ‘‘employment downsizing.’’

1.1. Downsizing and Organizational Decline

Employment downsizing is not the same thing as organizational decline. Downsizing is an intentional, proactive management strategy, whereas decline is an environmental or organizational phenomenon that occurs involuntarily and results in erosion of an organization’s resource base. For example, the advent of digital photography, disposable cameras, and other imaging products signaled a steep decline in the demand for the kind of instant photographic cameras and films that Polaroid had pioneered during the 1940s. On October 12, 2001, Polaroid was forced to declare bankruptcy.

1.2. Extent and Scope of Employment Downsizing

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, approximately 2 million people have been affected by employment downsizing each year since 1996. In 2001, for example, companies announced nearly 1 million job cuts during the 3 months after the terrorist attacks of September 11. Many firms conduct multiple rounds of employment downsizing during the same year as ongoing staff reductions become etched into the corporate culture. On average, two-thirds of firms that lay off employees during a given year do so again the following year.

The phenomenon of layoffs is not limited to the United States. They occur often in Asia, Australia, and Europe as well. Japan’s chip and electronics conglomerates shed tens of thousands of jobs during the first few years of the 21st century as the worldwide information technology slump and fierce competition from foreign rivals battered their bottom lines. In Mainland China, more than 25.5 million people were laid off from state-owned firms between 1998 and 2001. Another 20 million were expected to be laid off from traditional state-owned firms by 2006.

The incidence of layoffs varies among countries in Western Europe. Labor laws in countries such as Italy, France, Germany, and Spain make it difficult and expensive to dismiss workers. For example, in Germany, all ‘‘redundancies’’ must by law be negotiated in detail by a workers’ council, which is a compulsory part of any big German company and often has a say in which workers can be fired. Moreover, setting the terms of severance is tricky because the law is vague and German courts often award compensation if workers claim that they received inadequate settlements. In France, layoffs are rare. Even if companies offer generous severance settlements to French workers, as both Michelin and Marks & Spencer did, the very announcement of layoffs triggers a political firestorm.

2. Mergers, Acquisitions, And The Demise Of Loyalty

Worldwide, tens of thousands of mergers and acquisitions take place each year among both large and small companies. In general, after a buyout, the merged company eliminates staff duplications and unprofitable divisions. Employment downsizing is part of that restructuring process. Such restructuring often leads to similar effects—diminished loyalty from employees. Following takeovers, mergers, acquisitions, and downsizings, thousands of workers have discovered that years of service mean little to struggling managers or a new corporate parent. This leads to a rise in stress and a decrease in satisfaction, commitment, intention to stay, and perceptions of an organization’s trustworthiness, honesty, and caring about its employees.

Companies counter that today’s competitive business environment makes it difficult to protect workers. Understandably, organizations are streamlining to become more competitive by cutting labor costs and to become more flexible in their response to the demands of the marketplace. But the rising disaffection of workers at all levels has profound implications for employers. Perhaps one of the most fundamental issues to consider is the new meaning of loyalty. Today, workers and managers are less loyal to their organizations than ever before. As Reichheld has shown, U.S. companies on average now lose half of their employees in 4 years, half of their customers in 5 years, and half of their investors in fewer than 12 months.

So, what is the new meaning of loyalty? Employees at all levels are still loyal, but instead of being blindly loyal to their organizations, they are loyal to a vision or to a mission. They are loyal to mentors, prote´ ge´ s, or team members. As a result, more and more organizations are now thinking in terms of 3to 5-year employment relationships. Some are even adopting a strategy long used in the sports world, that is, fixed contracts with options for renegotiation and extension.

3. Corporate Financial Performance Before And After Downsizing

In a series of studies that included data from 1982–1994, 1995–2000, and 1982–2000, Cascio and colleagues examined financial and employment data from companies in the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500. The S&P 500 is one of the most widely used benchmarks of the performance of U.S. equities. It represents leading companies in leading industries and consists of 500 stocks chosen for their market size, liquidity, and industry-group representation. Cascio and colleagues’ purpose was to examine the relationships between changes in employment and financial performance. Each year, they assigned companies to one of seven mutually exclusive categories based on each company’s level of change in employment and its level of change in plant and equipment (assets). Then, they observed the companies’ financial performance (profitability and total return on common stock) from 1 year before to 2 years after the employment change events. They examined results for firms in each category on an independent basis as well as on an industry-adjusted basis.

In Cascio and colleagues’ most recent study, they observed a total of 6418 occurrences of changes in employment for S&P 500 companies over the 18-year period from 1982 to 2000. As in their earlier studies, they found no significant, consistent evidence that employment downsizing led to improved financial performance, as measured by return on assets or industry-adjusted return on assets. Downsizing strategies— either employment downsizing or asset downsizing— did not yield long-term payoffs that were significantly larger than those generated by ‘‘stable employers,’’ that is, those companies in which the complement of employees did not fluctuate by more than ±5%.

Thus, it was not possible for firms to ‘‘save’’ or ‘‘shrink’’ their way to prosperity. Rather, it was only by growing their businesses that firms outperformed stable employers as well as their own industries in terms of profitability and total returns on common stock.

3.1. Is Downsizing Always Wrong?

Sometimes, downsizing is necessary. In fact, many firms have downsized and restructured successfully to improve their productivity. They have done so by using layoffs as part of a broader business plan. In the aggregate, the productivity and competitiveness of many firms have increased during recent years. However, the lesson from the research described previously is that firms cannot simply assume that layoffs are a ‘‘quick fix’’ that will necessarily lead to productivity improvements and increased financial performance. The fact is that layoffs alone will not fix a business strategy that is fundamentally flawed.

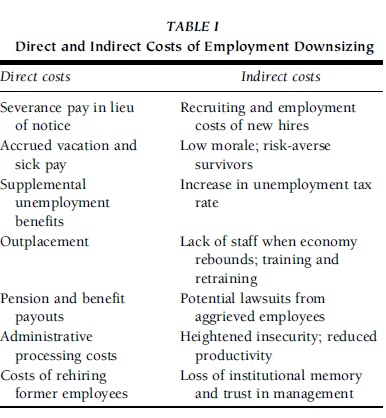

Employment downsizing might not necessarily generate the benefits sought by management. Managers must be very cautious in implementing a strategy that can impose such traumatic costs on employees—on those who leave as well as on those who stay. Management needs to be sure about the sources of future savings and carefully weigh those against all of the costs, including the increased costs associated with subsequent employment expansions when economic conditions improve. Table I shows direct and indirect costs of downsizing.

4. Effects Of Downsizing On Knowledge-Based Organizations

Knowledge-based organizations, from high-technology firms to the financial services industry, depend heavily on their employees—their stock of human capital—to innovate and grow. Knowledge-based organizations are collections of networks in which interrelationships among individuals (i.e., social networks) generate learning and knowledge. This knowledge base constitutes a firm’s ‘‘memory.’’ Because a single individual has multiple relationships in such an organization, indiscriminate, nonselective downsizing has the potential to inflict considerable damage on the learning and memory capacity of the organization. Empirical evidence indicates that the damage is far greater than might be implied by a simple tally of individuals.

TABLE I Direct and Indirect Costs of Employment Downsizing

TABLE I Direct and Indirect Costs of Employment Downsizing

When one considers the multiple relationships generated by one individual, it is clear that downsizing that involves significant reductions in employees creates the loss of significant ‘‘chunks’’ of organizational memory. Such a loss damages ongoing processes and operations, forfeits current contacts, and may lead to forgone business opportunities. Organizations that are at greatest risk include those that operate in rapidly evolving industries, such as biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and software, where survival depends on a firm’s ability to innovate constantly.

5. The Psychological Impact Of Downsizing On Victims And Survivors

Downsizing exacts a devastating toll on workers and communities. Lives are shattered, people become bitter and angry, and the added emotional and financial pressure can create family problems. ‘‘Survivors,’’ or workers who remain on the job, can be left without loyalty or motivation. A common experience is that employee morale is the first casualty in downsizing. Workplaces tend to be more stressful, political, and cutthroat than before the downsizing. Local economies especially cyber-sabotage, has emerged as a new threat among disgruntled ex-employees. Recently terminated workers have posted a company’s payroll on its intranet, planted data-destroying bugs, and handed over valuable intellectual property to competitors. Although exact numbers are hard to ascertain, computer security experts say that this is fast becoming the top technical concern at many companies.

5.1. Roles of Procedural and Distributive Justice in Employment Downsizing

Procedural justice focuses on the fairness of the procedures used to make decisions. Procedures are fair to the extent that they are consistent across persons and over time, free from bias, based on accurate information, correctable, and based on prevailing moral and ethical standards.

Distributive justice focuses on the fairness of the outcomes of decisions, for example, in allocating bonuses or merit pay or in making decisions about who goes and who stays in a layoff situation. In simple terms, it is the belief that all employees should ‘‘get what they deserve.’’

In the wake of decisions that affect employees, such as those involving pay, promotions, and layoffs, employees often ask, ‘‘Was that fair?’’ Judgments about the fairness or equity of procedures used to make decisions (i.e., procedural justice) are rooted in the perceptions of employees. Strong research evidence indicates that such perceptions lead to important consequences such as employee behavior and attitudes. As noted previously, when employees believe that they have not been treated fairly, they may retaliate in the form of theft, sabotage, or even violence. In short, the judgments of employees about procedural justice matter.

Procedurally fair treatment has been demonstrated to result in reduced stress and increased performance, job satisfaction, commitment to an organization, and trust. It also encourages organizational citizenship behaviors, that is, discretionary behaviors performed outside of one’s formal role that help other employees to perform their jobs or that show support for and conscientiousness toward the organization. These include behaviors such as the following:

- Volunteering to carry out activities that are not formally a part of one’s job

- Persisting with extra enthusiasm or effort when necessary to complete one’s own tasks successfully

- Helping and cooperating with others

- Following organizational rules and procedures, even when they are personally inconvenient

- Endorsing, supporting, and defending organizational objectives

Procedural justice affects citizenship behaviors by influencing employees’ perceptions of organizational support, that is, the extent to which the organization values employees’ general contributions and cares for their wellbeing. In turn, this prompts employees to reciprocate with organizational citizenship behaviors. These effects have been demonstrated to occur at the level of the work group as well as at the level of the individual. In general, perceptions of procedural justice are most relevant and important to employees during times of significant organizational change. When employees experience change, their perceptions of fairness become especially potent factors that determine their attitudes and behaviors. Employment downsizing is a major change for people, whether victims or survivors. Thus, considerations of procedural justice will always be relevant.

6. Outplacement: Easing The Career Transition Process

Outplacement is an extension of the termination process. It typically includes two elements: (a) counseling the employee who has lost his or her job for emotional stress resulting from the trauma of termination, and (b) assisting with job search. Its premise is that the sooner the terminated employee is reemployed, the less time he or she has to become disgruntled, to file a lawsuit, and/or to cause problems for those who remain, particularly through violence or sabotage.

Employment downsizing often creates anxiety or resentment among remaining employees. Some workers might feel that the departing employee received unjust treatment. Others may doubt their own job security and resent the upheaval and additional workload caused by a coworker’s departure.

Outplacement can help to address these issues. It provides firing managers with training and procedures to minimize trauma to the workers affected and disruption within the affected department. It helps survivors to see their organization as a fair and considerate employer. Among those downsized, outplacement can mitigate the damaging effects of unemployment on family life by including the terminated employee’s spouse in counseling sessions. Subsequent career assessment and job-search assistance may include activities such as an interest inventory as well as ‘‘how to’’ advice on building a re´ sume´ and doing well in a job interview. These activities focus on helping the terminated employee to identify his or her strongest skills and career preferences, to negotiate job offers, and to select the best placement.

References:

- Cascio, W. F. (1993). Downsizing: What do we know? What have we learned? Academy of Management Executive, 7(1), 95–104.

- Cascio, W. F. (2002a). Responsible restructuring: Creative and profitable alternatives to layoffs. San Francisco: Berrett– Kohler.

- Cascio, W. F. (2002b). Strategies for responsible restructuring. Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 80–91.

- Cascio, W. F., & Young, C. E. (2003). Financial consequences of employment-change decisions in major U.S. corporations: 1982–2000. In K. P. De Meuse, & M. L. Marks (Eds.), Resizing the organization: Managing layoffs, divestitures, and closings—Maximizing gain while minimizing pain (pp. 131–156). San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

- Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A metaanalytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

- De Meuse, K. P., & Marks, M. L. (Eds.). (2003). Resizing the organization: Managing layoffs, divestitures, and closings— Maximizing gain while minimizing pain. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

- Greenberg, J. (1997). The quest for justice on the job. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gutknecht, J. E., & Keys, J. B. (1993). Mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers: Maintaining morale of survivors and protecting employees. Academy of Management Executive,7(3), 26–36.

- Kanovsky, M. (2000). Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organizations. Journal of Management, 26, 489–511.

- Kleinfeld, N. R. (1996, March 4). The company as family no more. The New York Times, pp. A1, A8–A11.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass.

- Reichheld, F. F. (1996). The loyalty effect. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Schweiger, D. M., & Denisi, A. S. (1991). Communication with employees following a merger: A longitudinal field experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 110–135.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.