This sample Elder Abuse Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Elder abuse is a social and public health problem that affects over half a million abused elderly victims in the United States as well as their caregivers, family, and community institutions. Abuse results in physical, emotional, and mental angst for victims, some of whom are cognitively and/or functionally impaired. There are also societal economic repercussions of elder abuse due to the increased need and demand for greater health care and social services to assist the victims. Although health care and law enforcement participation have helped assuage the situation, elder abuse detection, assessment, and treatment remain challenging. Adding to the difficulty of combating elder abuse is the geriatric population, which is predicted to increase the strain on caregivers and societal institutions. This stress may perpetuate greater incidences of elder abuse in the future. Currently, multidisciplinary teams of psychologists, physicians, social workers, and public health advocates work together to educate, prevent, and intervene earlier in potential elder abuse cases. This research-paper discusses the ways in which professionals are attempting to ameliorate elder abuse, in addition to providing a brief background of the causes and effects of this problem. The discussion includes methods of identifying victims and abusers, assessment of abuse, methods of intervention, and factors to account for in treatment.

Outline

- Introduction

- Law

- Theories of Abuse: Risk Factor Profiles

- Clinical Management of Elder Abuse

- Ethical Issues

- Future Directions

- Summary

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Elder abuse has been a phenomenon recognized in medical and social practice since the 1970s, when the terms ‘‘granny battering’’ and ‘‘granny bashing’’ were mentioned in literature from the United Kingdom. In the same decade, work on aging populations established the presence of similar incidents in the United States. Terms such as elder mistreatment, elder abuse, and battered elders syndrome have variously attempted to describe abuse against elderly individuals.

1.2. Definition

The Institute of Medicine defines elder abuse (or elder mistreatment) as (1) intentional actions that cause harm or create a serious risk of harm (whether or not harm is intended) to a vulnerable elder by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder, or (2) failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elder’s basic needs or to protect the elder from harm. While the terms elder mistreatment and elder abuse are frequently used to describe this behavior, the term elder abuse will be used in this research-paper.

1.3. Types of Abuse

Elder abuse occurring either in the home or in an institution can be described as one or more of the following types: physical abuse, neglect, psychological abuse, financial abuse, and sexual abuse. This research-paper focuses on the issues of elder abuse as it occurs in the home.

1.3.1. Physical

Physical abuse is an act that may result in pain, injury, and/or impairment. Physical abuse includes bodily harm, neglect by others, medication misuse, and medical mismanagement. Bodily harm or physical assault can take many forms, such as beating, shaking, tripping, punching, burning, pulling of hair, slapping, gripping, pushing, pinching, kicking, and the use of physical restraints.

1.3.1.1. Neglect and Self-Neglect

Neglect, which is considered a type of physical abuse, can either be intentional or unintentional. Intentional neglect is the deliberate failure to provide the basic needs of the elder. It also includes the failure to provide goods or services that are necessary to avoid or prevent physical harm, mental anguish, or mental illness. Unintentional neglect occurs when the caregiver is not knowledgeable about the elder’s needs or when the caregiver is restricted in the care they can provide due to his or her own infirmities.

Self-neglect is a failure to engage in activities that a culture deems necessary to maintain socially accepted standards of personal or household hygiene and to perform activities needed to maintain health status. Self-neglect has been categorized as a type of physical abuse by some authors. The highest national percentage of reported cases of abuse are those of self-neglect.

1.3.2. Psychological/Emotional Abuse

Psychological and/or emotional abuse can occur independently or can be related to physical abuse such as neglect or other forms of abuse. It is a deliberate act inflicted on the elder that is intended to cause mental anguish. Psychological abuse may include isolation, verbal assault (name calling), threats that induce fear (intimidation), humiliation, harassment, ignoring, infantilization, and emotional deprivation.

1.3.3. Financial Abuse

Financial abuse is the misuse of an older person’s funds or theft of money, property, or possessions.

1.3.4. Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse involves forcing the elder to take part in any unwanted sexual activity, such as touching that makes the elder feel uncomfortable or photographing the elder person while he or she is changing clothes or bathing.

1.4. Epidemiology of Abuse

The National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA) reports that in 1996 an estimated 551,011 persons aged 60 and over experienced abuse, neglect, and/or self-neglect in a 1-year period. The report also adds that there were four times as many new, unreported cases of elder abuse. Another study noted that more than 105,000 elderly Americans were victims of non-fatal violent crimes in 2001.

An anticipated increasing geriatric population is predicted to expand the elder abuse problem. According to the 2000 U.S. census, the number of individuals over the age of 65 has increased from 31.2 million in 1990 to 35 million in 2000. Population specialists predict that with these continuing trends, by the mid-21st century there will be more elderly people than young people in the United States. The increasing number of senior citizens creates greater dependency on the immediate and extended family and demand for health and social services to accommodate to the increased longevity and chronic medical care of the elderly. Higher costs of health care, inadequate support for caregiving, and personality conflicts between the elder and the family or caregiver can strain relationships and may contribute to the possibility of abuse.

2. Law

Federal policymakers first addressed the issue of elder abuse through the Older Americans Act of 1965, which was followed by the Vulnerable Elder Rights Protection Program in 1992. Since then, states have developed their own laws governing elder abuse management. State elder abuse statutes have primarily been based on laws developed to address child abuse and spousal/ intimate partner abuse. The primary focus of elder abuse laws in most states has been mandatory reporting statutes and follow-up investigational procedures. Forty-two states have mandatory reporting laws, and eight states have voluntary reporting requirements. Psychologists are mandated reporters in 29 states and are encouraged to report elder abuse in five states. The investigating agency and the scope of authority of the agencies varies from state to state, but the Adult Protective Services (APS), the Long-Term Care Ombudsman, and the local law enforcement agency are the most commonly recognized organizations to whom a report can be made about suspected or confirmed elder abuse. Penalties for not reporting elder abuse, the time frame for emergency reports, and the maximum length of investigation also depend on the state. It is recommended that interested parties become familiar with the reporting requirements specific to each state (http://www.elderabusecenter.org).

3. Theories Of Abuse: Risk Factor Profiles

The literature suggests that all older adults may be at risk of abuse. Reviews of the literature have found conflicting profiles of both victims and possible abusers, indicating that it is not fitting to eliminate any particular profile; nor is it appropriate to say that a typical profile exists. The following sections discuss factors clinicians should be aware of when working with older adults.

3.1. Impairment of the Elder

Alcohol abuse by the elder is one of the most common risk factors for elder abuse. Although research shows variations in the impact of alcohol abuse on elder abuse, it has been found that the victim’s risk for elder abuse could increase up to 10-fold. Other commonly established risk factors for elder abuse include low cognitive abilities and physical functional impairment. Those with depression, dementia and psychiatric illness are more likely to be abused. Elders who have difficulty eating are also at greater risk of abuse. These impairments may lead elders to live with family members. Elders are more likely to be abused if they live with family but do not have a living spouse. This places women, who are more likely to be widowed, at a greater risk for abuse. However, women may also be abused when they care for a spouse who may have been or continues to be abusive.

3.2. Perpetrator Characteristics

Other risk factors of elder abuse have also been proposed. Anetzberger suggested that elder abuse is primarily a function of the perpetrator’s characteristics. This means that the caregiver’s problems, pathologies, and perceptions may be the key to understanding who becomes an abuser. Per G. Anetzberger, life stresses, financial problems, mental disabilities, and lack of empathy for older people with disabilities may render some caregivers ‘‘ill-suited for caregiving and, given the potential dynamics associated with caregiving, can make them prone to inflict abuse’’ (2000, p. 48). Research from the Three Model Projects on Elder Abuse found that in many cases the abuser was emotionally or financially dependent on the victim. Substance abuse by the caregiver was also related to risk for elder abuse.

3.3. The Interaction between Caregiver and Care Receiver

The caregiver–elder relationship also affects the potential for abuse. Risk may increase if the caregiver perceives the care recipient as difficult, combative, excessively dependent, or any combination of these. Homer and Gilleard found that socially disruptive behavior by the care receiver was related to elder abuse. However, others have found no such relationship. The duration, type, and intensity of care needed, cultural values, and individual family expectations also contribute to the possibility of abuse. Among ethnic minority caregivers, burden may be less likely to be an issue expressed by caregivers. Some studies have found risk factors associated with non-white or ethnic minority populations.

3.4. Multi-Factor Clinical Assessments

Given the conflicts that have emerged in research, the prudent clinician will continue to use all of these factors in his or her assessments. Many clinicians often overlook the importance of understanding the caregivers of older adults. Clinicians should recognize that caregiving is a risk factor for abuse, and paying close attention to the caregivers’ attitude toward their roles may be useful in preventing abuse from occurring or being overlooked. Therefore, they need to observe the dynamics of the family relationship when meeting either the caregiver or the care receiver.

4. Clinical Management Of Elder Abuse

Elder patients can self-refer or be referred for a psychological review by their primary care physician or other health care provider. Whether the health care provider refers elders for suspected elder abuse or for changes in emotional and/or psychological and cognitive status, it is necessary that psychologists always screen elder patients for incidences of abuse.

The theoretical model that guides clinical management is described more fully in a 2003 Institute of Medicine Report. This model is adapted from Engel’s biopsychosocial model. According to the elder abuse model, the social, physical, and psychological characteristics of the elder interact with those of the caregiver or trusted other. The interaction between the elder and the caregiver or trusted other person occurs in an environment governed by the socioeconomic conditions of the involved parties, the level of economic dependency, and the normative expectation of other stakeholders (health care personnel, social service agencies, friends, and relatives). Also important to the interaction between the caregiver and the elder is the sociocultural context in which they live, which encompasses the institutional or organizational locus (such as nursing home, private household), race or ethnic group, and social network of the elder and caregiver. The presence of social ties of the stakeholders to the elder and the caregiver may serve as a monitoring control on their interaction. Literature suggests that absence of this social network increases the vulnerability of the elder to the risk of abuse.

The physical, mental, and emotional health outcomes of the interaction between the elder and the caregiver impact their future behavior. These outcomes continually feedback to and remold the elder’s and caregiver’s social, physical, and psychological characteristics that will produce new outcomes. The feedback loop may sometimes result in the occurrence of abuse, either as a one-time incident or as a progression of violent episodes. This process-oriented model can help expand understanding of the etiology of specific types of elder abuse, help develop suitable interventions, and eventually lead to a reversal of the process.

4.1. General Evaluation and Analysis

4.1.1. Approach

The person who elicits the elder’s history during a clinical visit should be patient and tolerant. Elders who arrive at a clinic for assessment may speak slowly. It is important to talk clearly and slowly to an elder patient, as he or she may have hearing impairments. Care should be taken not to infantilize the patient and not to subscribe to ageist attitudes and myths about the elderly such as forgetfulness, senility, dependency, ineptness, unproductivity, and unattractiveness. Cultural and ethnic differences between the physician and patient must be respected and considered. Tact, belief, and discretion are paramount to developing a trusting relationship with the patient.

4.1.2. Observation

Anyone who assesses an elder for signs of abuse needs to pay close attention to patient–caregiver interactions. Increased discomfort, silence or monosyllabic responses, and fear exhibited by the patient when the caregiver is present may be indicators of elder abuse. In such situations, it is advisable to interview the patient when the caregiver is not present. Patients’ responses and body language need to be critically observed. Fear, anger, infantile behavior, agitation, rocking (in the absence of other motor diseases), and sucking are some behavioral responses that may indicate possible abusive situations in the patient’s life. Other indicators include, but are not limited to, confusion or disorientation while providing responses, withdrawal, denial of events and happenings, failing to talk openly, and providing implausible stories. Physical signs provide vital clues to possible elder abuse incidences. Cuts, lacerations, bruises, welts, dehydration, loss of weight, and burns should raise suspicion of abuse.

4.1.3. History Taking

4.1.3.1. Past History

Theories about elder abuse indicate the role of transgenerational violence as a high risk factor for violence against a senior adult. Past history of domestic violence in the life of the victim (either as the perpetrator or the victim) needs to be elicited with a nonjudgmental and sensitive approach. A history of past relationships, family dynamics, the number of household members, education levels, and available societal resources such as visits from friends, other relatives, and neighbors provide clues to detect isolation and incidences of neglect. History of substance abuse (alcohol and or chemical dependency), employment status, housing, and financial status provide insights into possible cases of dependency and potential abuse. Sexual history should also be considered.

4.1.3.2. Family History

Death of a spouse or partner and history of alcoholism among family members are areas that need to be explored. Serious psychiatric disorders in the family might provide a clue to the level of caretaking and dependency that the elder might be responsible for in his or her home.

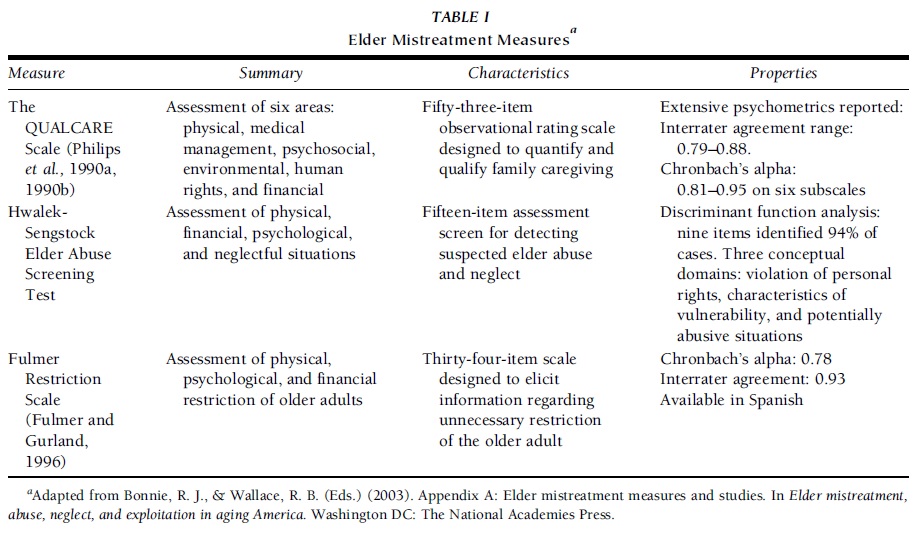

4.1.4. Screening

Detection of elder abuse can be accomplished by routinely screening for abuse. The American Medical Association urges every clinical setting to use a routine protocol for the detection and assessment of elder mistreatment. There are several instruments available for screening the patient and/or the caregiver. Table I contains a list of screening methods and instruments along with information on their measurement properties. Once a case is identified as suspected positive, an intervention plan has to be developed and applied with the consent of the patient. The following sections describe other assessments that aid in identifying incidences of elder abuse.

4.2. Assessment of Cognitive Status and Personality of the Patient

Psychological assessment of an elder should include a comprehensive assessment of age-related conditions such as anxiety disorders, depression, mood disorders, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, substance abuse, and personality. Especially important are those tests that assess for risk factors of elder abuse, such as alcohol abuse and depression. The American Psychological Association recommends the following measures for assessing the psychological and cognitive status of the elder patient: The Beck Anxiety Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and other oral and written forms of depression-assessing instruments such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Some authors also recommend the Beck Depression Inventory or the Yesavage Depression Scales. The CAGE instrument assesses alcohol usage. Additionally, the geriatric version of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test can be specifically used with older adults. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale or Cummings Inventory for Alzheimer’s Dementia helps evaluate dementia.

Health care providers need to look for overt and covert clinical signs of the patient’s psychological and cognitive status during evaluations. Overt signs such as crying, silence, and irritability indicate a possible depressive state or social withdrawal; they could also be learned passive behavior. Prior to performing any assessments, the elder patient should be familiarized with the tests and procedures. Elders should have appropriate assistive devices such as eyeglasses and hearing devices. For those who are non-English speakers, the tester should be able to converse in the language spoken by the elder or seek the assistance of a professional interpreter.

TABLE I Elder Mistreatment Measures

TABLE I Elder Mistreatment Measures

4.3. Risk Factor Assessment

An assessment of possible risk factors by a home care team or social worker can help identify needs and possible resources. Incidences of substance abuse, the availability of a caregiver and/or a support system from the patient’s family or friends, financial dependency on the patient by other family members, and caregiver stress are factors that influence the plan of action. Any course of action that is recommended by the psychologist should be relayed to the elder’s primary care physician. Available options should be discussed with the patient and the social worker if possible.

4.4. Treatment and Management

Once suspicion of elder abuse has been confirmed, the next step is to establish a plan of action to minimize the abuse or effects of abuse. A safety assessment is performed to ensure that preventive measures are adapted to the elder’s needs. The elder’s physical appearance, home environment, and personal surroundings should be considered when determining the immediacy of danger. A multidisciplinary team of professionals should be involved in the diagnosis, management, and prevention of suspected elder mistreatment.

If the elder is in imminent danger, immediate action should be taken to remove the elder from the situation. One possible method of intervention is to admit the elder to the hospital. In the hospital, the elder will receive medical treatment and not be endangered. Less serious cases of suspected elder abuse can be dealt with through continuous monitoring of the elder. A safety plan may also be developed to ensure that the elder knows what to do if placed in a compromising situation. This may include packing a bag of clothes and keeping copies of important papers, keys, money, and other necessary articles to take if the elder needed to quickly leave his or her home.

If the danger involves the caregiver’s burden, an intervention should be designed to lessen the stress of the caregiver through services including home health aides, adult day care, and other types of respite programs. Community resources should also be consulted for possible safety, educational, caretaking, and social support services.

When determining a plan of action, it is important to consider the capacity of the elder and the caregiver, due to the need for cooperation of both parties and the desire to accommodate the individual to whom services are directed. One such method of intervention is psychotherapy. However, no specific psychological intervention is preferred for elders. Instead, treatment options are individualized, led by the nature of the problem, therapeutic goals, preferences of the involved elder, and convenience for the involved parties. During psychotherapy, the psychologist must remember to be culturally sensitive and respectful of the individual’s race, gender, sexual orientation, and social class when assessing issues of mistreatment and formulating interventions. The psychologist should also be attentive to the sensory deficits of the elder, particularly hearing and vision loss, which may hinder communication. Last, psychologist should consider whether psychological symptoms are caused or exacerbated by underlying medical problems. This will enhance the patient– psychologist relationship and enable more effective and productive therapy sessions.

Another method of intervention is education. Elders can learn how to protect themselves and gain empowerment through education. Education may be used to assist psychological interventions by providing additional information regarding the rationale, structure, and goals of psychotherapy. Psycho-education can also help families caring for cognitively impaired elders. It can familiarize the family with the nature of cognitive loss, problem solving for practical problems, and providing emotional support to cognitively impaired elders who have experienced abuse. Additionally, education teaches other professionals about aging and how to investigate suspected elder abuse. These professional can advocate for the safety of elders while providing psychological services to this population.

Physicians can also prescribe medications to elders to cope with the involved abuse. These prescriptions may enable elders to function well within society or address the repercussions of the abuse. If an elder is abusing his caregiver, medication may be used to normalize the elder’s behavior and prevent him or her from doing further harm.

Patient/family cooperation should also be considered when creating a plan of action. For the plan to be useful, it must be implemented by the assisting family. Thus, interventions that consider abused elders’ families and their shared values are needed. If the family of the abused elder disagrees with the chosen method of intervention, it is suggested that psychologists be sensitive to the family’s opposition and work with them to create modifications to an intervention.

The key to success in each of these intervention methods is the follow-up process. To determine the efficacy of the proposed intervention, the elder or caregiver must be contacted to ensure that the elder’s needs are being met, that a safe environment is preserved, and that wellness of the abused individual is maintained. If interventions are ineffective, physicians must modify their plan of action by re-evaluating the abused elder’s needs. One reason that physicians may need to re-evaluate action plans is a change in the elder’s access to resources. Interventions must consider the elder’s standard of living. This will guarantee the potential for intervention use by the abused elder.

An additional note of concern involves identifying potential challenges to suggested interventions. Challenges may include the resistance of elders to disclosing their personal experiences of neglect or abuse. This resistance may be associated with feelings of embarrassment or shame involving their mistreatment. Elders may also feel uncomfortable with the notion of receiving mental health services for their abuse. Their reservations require physicians to attend to their needs through reassurance of confidentiality during scheduled meetings, by participating in active listening with the elders, and by actively engaging with elders and their caregivers. This may require the enlistment of an individual who has a trusting relationship with the abused victim.

One specific way to counter sentiments of resistance is to validate both the positive and the negative feelings expressed by family members and victims. This validation will cause resistance to slowly diminish as elders begin to feel that their physician is trustworthy and wants to help them. This gradual progression toward an open relationship will foster an environment suitable for the disclosure of sensitive material.

Intervention efforts may be impaired if the elder is cognitively unaware. Should the abused elder suffer cognitive impairment, it is necessary for psychiatrists or geriatricians to ensure that the elder receive adequate care from a reliable caregiver. If the caregiver is a possible abuse perpetrator, or if he or she is unable to handle the elder’s impairment, additional respite care or institutionalization should be considered.

5. Ethical Issues

When developing interventions in elder abuse cases, the clinician needs to be cognizant of the basic principles of autonomy, justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence.

5.1. Autonomy

Autonomy is the right of self-determination. It is the right to choose one’s actions or course in life as long as they do not interfere unduly with the lives and actions of others. A clinician must respect the options and choices made by the elder in regards to his or her living situation and caregiver. If the patient decides to continue living in the abusive situation, written information regarding emergency assistance, a follow-up plan, and a safety plan should be developed in consultation with the victim. However, it is imperative to assess the cognitive status and mental stability of the elder and caregiver.

5.2. Justice

The principle of justice allows everyone the right to that which he or she is due. Some elder patients may not receive adequate care because the caregiver and/or family is exploiting the finances of the patient. Although the caregiver may use the patient’s funds to care for the elder, any unequal distribution of resources that jeopardizes the health and well-being of the elder and that which is done against the wishes of the elder is a violation of the rights of the patient.

5.3. Beneficence and Maleficence

Any intervention that is developed to address elder abuse should do no harm to the patient. The psychologist developing interventions should consult the patient, the patient’s doctor, and the social worker before deciding on a course of action. Decisions that raise ethical dilemmas should be weighed for the merit of potential good in relation to the potential harm. This involves recognizing the limitations of the available resources for the patient, the caregiver, and the cognitive and general health of the patient and the caregiver.

6. Future Directions

Psychologists and other public health personnel should educate the public about elder abuse. Culturally relevant materials and messages tailored to suit the needs of minorities conveyed in English and other languages will help inform the general public about the issue. Information for caregivers on their role and the availability of resources in the community will improve early detection and management of elder abuse. Advocacy for the rights of elders, especially in the area of mental health, to support their social and emotional well-being is necessary. Collaborative research with community organizations and academic institutions involved in research will help identify new areas for development.

7. Summary

Forms of elder abuse include physical abuse, neglect, psychological abuse, financial abuse, and sexual abuse. These types of abuse may occur independently or coexist with another form of abuse and may be difficult to detect. When assessing for signs of abuse, a clinician should pay attention to visible marks as well as emotional and mental expressions of fear, anger, confusion, and sadness. The caregiver’s circumstance, competency, and relationship to the elder should also be considered in the assessment. One difficulty in recognizing and diagnosing potential elder abuse is that its symptoms and risk factors may resemble otherwise normative age-related illnesses such as dementia and depression. Also, no typical profile exists for either the caregiver or the victim. When assessing for abuse, a range of psychological tests should be performed and extensive past histories and current circumstances should be elicited to gain a full understanding of the elder’s situation. After diagnosis, possible methods of intervention include psychotherapy, psychoeducation, and separation of the elder from the caregiver. In formulating an intervention, the needs and abilities of the victim and caregiver should be taken into consideration, as must the rights of the victim. Plans of actions should be routinely re-evaluated to judge the intervention’s effectiveness and should be adjusted according to changes in the circumstances of the victim and caregiver. The clinician should approach the process of assessment to intervention with patience for disabilities that the elder might have and without discriminating against factors such as age, culture, gender, and social class.

References:

- Abeles, N., & The APA Working Group on the Older Adult Brochure. (1997). What practitioners should know about working with older adults. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved on December 3,2003 from http://www.apa.org/pi/aging/practitioners.pdf.

- American Medical Association. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment guidelines on elder abuse and neglect. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association. Retrieved on December 9, 2003 from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/386/elderabuse.pdf.

- Anetzberger, G. J. (2000). Caregiving: Primary cause of elder abuse? Generations, 24, 46–51.

- Beauchamp, T., & Childress, J. (1994). Principles of biomedical ethics (4th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Benton, D., & Marshall, C. (1991). Elder abuse. Geriatric Home Care, 7, 831–845.

- Bonnie, R. J., & Wallace, R. B. (Eds.) (2003). Elder mistreatment: Abuse, neglect, and exploitation in aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Dyer, C. B., Pavlik, V. N., et al. (2000). The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 205–208.

- Engels, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for bio-medicine. Science, 196, 129–136.

- House, J. S., Umbersome, D., & Landis, K. R. (1988). Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318.

- Lachs, M. S., Berkman, L., et al. (1994). A prospective community-based pilot study of risk factors for the investigation of elder mistreatment. Journal of the American-Geriatrics Society, 42, 169–173.

- Lachs, M. S., Williams, C., et al. (1997). Risk factors for reported elder abuse and neglect: A nine-year observational cohort study. The Gerontologist, 37, 469–474.

- Lauder, W., Scott, A. P., & Whyte, A. (2001). Nurses’ judgements of self-neglect: A factorial survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38, 601–608.

- Lin, N., Ye, X., & Ensel, W. E. (1999). Social support and depressed mood: A structural analysis. Journal of Health Behavior, 40, 344–359.

- The National Center on Elder Abuse at The American Public Human Services Association. (1998). The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study Final Report. Washington, DC: National Center on Elder Abuse. Retrieved on November 19, 2003 from http://www.aoa.gov/eldfam/Elder_Rights/ Elder_Abuse/ABuseReport_Full.pdf.

- Paveza, G. J., Cohen, D., et al. (1992). Severe family violence and Alzheimer’s disease: Prevalence and risk factors. The Gerontologist, 32, 493–497.

- Pay, D. S. (1993). Ask the question: A resource manual on elder abuse for health care personnel. Vancouver, Canada: BC Institute Against Family Violence. Retrieved on November 13, 2003 from http://www.bcifv.org/pubs/ask_question.html.

- Quinn, M. J., & Tomita, S. K. (1997). Elder abuse and neglect: Causes, diagnosis, and intervention strategies (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Co.

- Rennison, C. (2002). Criminal victimization 2001: Changes 2000–2001 with trends 1993–2001. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved on January 30, 2004 from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/ pub/pdf/cv01.pdf.

- Sandefur, R., & Laumann, E. O. (1998). A paradigm for social capital. Rationality and Society, 10, 481–501.

- S. Census. (2002). United States Census 2000. Washington, DC: U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on November 15, 2003 from http://www.census.gov.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.