This sample Elder Caregiving Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Caregiving for older adults is a prominent occurrence in the daily lives of many Americans. It is a topic that has received considerable attention from a variety of sources, including research, popular media, and society as a whole. This research-paper offers an overview of the current body of knowledge in the field, including but not limited to specific topics such as the stressors associated with caregiving, the impact of caregiving, and interventions that may be beneficial.

Outline

- Introduction

- Overview of Elder Caregiving

- Stressors of Caregiving: What Do Caregivers Do?

- Individual Differences in Reaction to Caregiving

- Racial and Ethnic Diversity Issues

- Biopsychosocial Impact of Caregiving

- Interventions for Caregivers

- Concluding Comments

1. Introduction

This research-paper provides an overview of important issues faced by family caregivers, a topic that is of increasing interest in our society. Although illness and disability can strike at any time in the life cycle and lead to care by family members, this research-paper focuses on caregivers for older adults. It reviews the importance and growth of family caregiving; stress process models used to guide research and clinical practice; common stressors faced by family caregivers; the impact of caregiving on psychological, social, and health functioning; individual differences in response to caregiving; and psychosocial interventions for caregivers.

2. Overview Of Elder Caregiving

As the population ages and an increased number of individuals are faced with the responsibility of caring for aging loved ones, the topic of elder caregiving becomes increasingly prominent as an area of research, clinical practice, and public policy. Broadly defined, caregivers are individuals who provide assistance of varying levels to other people who are unable to perform these tasks for themselves. Often the term ‘‘caregiver’’ is associated with a group of individuals who are thought of as homogenous; however, the open nature of the definition allows a high degree of variability within this group. One important distinction is that caregivers can be either paid (formal) or unpaid (informal). Formal caregivers are those who receive financial compensation for the services they perform (e.g., nurses, home health aides), whereas informal caregivers are those who volunteer their time to assist loved ones (e.g., family members, friends). It is estimated that between 80 and 90% of individuals with physical impairments reside in the community and receive the vast majority of their care from informal sources.

The cost of informal caregiving in the United States, including things such as lost wages, keeping an individual out of a nursing home, and performing tasks that otherwise someone would have to be hired to do, was estimated to be $196 billion in 1997, the year of the most recent national reliable estimates. This dollar figure is more than twice the amount estimated for nursing home care during that same year. Informal caregiving, although substantially less of an economic cost to the family members compared with institutional care, is often coupled with a number of other physical, psychological, and social costs to the individual (discussed in greater detail later).

Individuals choose to take on the responsibility of caring for a loved one for a variety of reasons, including economic conditions, perceived obligation, a cultural ethic that caregiving is expected, and a positive desire to provide care as a meaningful and worthy activity. Formal care for a chronically ill individual is very expensive, whether provided by professionals who come into the home, in an assisted living facility, or in a nursing home. Medicare and Medicaid rarely cover such services fully; thus, many families simply cannot afford such care. However even in situations where financial considerations are not the primary concern, many families consider it their duty to provide the necessary care and keep their loved ones at home. It is also common for caregivers in these situations to report that they believe they can provide better care than can staff members who do not have personal relationships with their loved ones.

3. Stressors Of Caregiving: What Do Caregivers Do?

Depending on the nature of the illness, caregivers may face a variety of daily demands. These can include impairments in self-care and cognition as well as development of changes in personality and behavior. Other stressors can include physical care demands and issues specific to end-of-life caregiving.

Self-care impairments include higher level instrumental activities of daily living (IADLS) and more fundamental activities of daily living (ADLs). IADLs include tasks such as managing finances, housekeeping, using transportation, and taking medications independently. Loss of independence in IADLs occurs relatively early in the course of progressive dementias but can also occur due to less serious medical problems (e.g., arthritis) that may limit mobility. ADL impairment occurs during middle and later phases of dementia and includes loss of independence in fundamental skills such as bathing, dressing, feeding, and continence of bowel and bladder. Family caregivers who assist with self-care impairments may provide only minor intermittent assistance (e.g., assistance in balancing a checkbook). Assistance with personal care, such as bathing and managing incontinence, is more psychologically stressful because it may involve embarrassing personal care. With assistance with ADLs and IADLs, families may face issues such as role reversal.

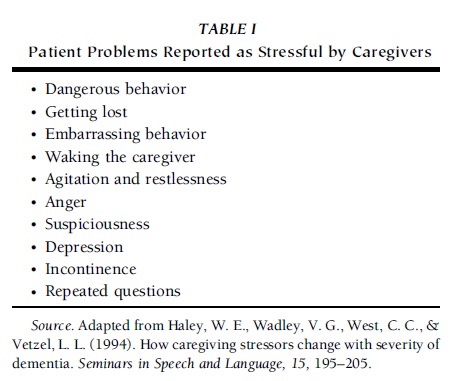

Cognitive impairment produces its own unique stressors. In addition to producing decrements in ADL and IADL functioning, dementia can lead to problems such as becoming disorientation, repeating questions, and forgetting to do tasks. Dementia also leads to behavioral problems such as wandering, agitation, and delusional behavior. Table I lists 10 patient problems reported to be the most stressful by a large sample of caregivers for older adults with dementia. Of particular note is that behavioral problems were reported to be much more stressful than self-care problems—even incontinence.

TABLE I Patient Problems Reported as Stressful by Caregivers

TABLE I Patient Problems Reported as Stressful by Caregivers

Caregiving for persons with terminal illness creates additional stressors. Beyond the actual tasks of caregiving, other issues include stressors that are more difficult to define. One of these is witnessing the suffering of the care recipients. Caregivers may also be responsible for management of complex medical regimens.

Interaction with the formal care system can be another important stressor. Caregivers report that it is very difficult to negotiate care, manage in-home assistance, and deal with nursing homes. Research has also shown that when caregivers receive formal assistance, it does not decrease their involvement in or commitment to informal caregiving; instead, it simply supplements the informal caregiving activities.

A national survey of family caregivers conducted in 1996 found that the overall mean number of hours of care per week was 17.9; however, this number ranged from 3.6 hours for individuals whose relatives were mildly impaired to 56.5 hours for those whose relatives had significant physical and/or cognitive disabilities. In addition, the stage of the illness is a major factor in affecting how much care a person provides. Research examining spousal caregivers of persons with end-stage lung cancer in hospice has shown that an average of 120 hours per week of care is provided by these individuals. The actual services performed by family caregivers can vary from occasional shopping and household assistance for a frail elder; to assistance with bills and organization for an individual with early stage dementia; to assistance with dressing, bathing, and ambulation for an individual who has suffered a moderate stroke; to complete responsibility for toileting, eating, and medications for an individual with end-stage cancer.

To get a better understanding of the broader picture of caregiving in the United States, the National Caregiver Survey was conducted in 1996. This study included 1500 family caregivers of individuals with both dementia and non-dementia diagnoses and provided very valuable insight into the differences between the two. The participants in this study had been providing care for slightly longer than 5 years regardless of diagnosis; however, the dementia caregivers reported significantly more hours per week in the caregiving role. In addition, a significantly higher percentage of dementia caregivers were providing care for each of the ADLs surveyed than were non-dementia caregivers. These findings suggest that the dementia caregivers in this study experienced greater demands while in the caregiving role, which apparently carried over into other areas of their lives. The dementia caregiving group reported greater impacts in terms of family conflict, caregiver strain, time for leisure and other activities, and mental and physical health problems.

4. Individual Differences In Reaction To Caregiving

A number of studies have shown that high levels of stress experienced by caregivers of elders, in particular those with Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia, often lead to a number of negative psychosocial and health outcomes such as feelings of burden, social isolation, depression, and health problems. However, although most caregivers endure immense stress, they vary in their ability to cope successfully. Researchers have found that it is not necessarily the objective level of stress experienced by caregivers that affects their mental and physical health; rather, it is actually a combination of factors, including context of the caregiving experience, individual appraisal of the caregiving role and competence in that role, coping style, and social support.

First, the context variables, such as the caregiver’s gender, age, and health, the quality of the caregiver’s relationship to the care recipient, and the length of time providing care, are believed to exert influence throughout the caregiving experience. Socioeconomic status, such as income and education, can affect caregiving outcomes, including morbidity and mortality. It is well established that there is a negative relationship between socioeconomic status and chronic morbidity and mortality, especially among older persons. Socioeconomic characteristics can exert an indirect effect via stress, social relations, and/or health status.

It is common for one individual to take on the role of primary caregiver, with women being the most likely to provide care either for themselves or for their own spouses. It is estimated that 70% of all family caregiving responsibilities are taken on by women and that more than 50% of all women provide this type of care at some point in their life courses. This is significant because studies that examine the effect of gender on the caregiving experience have consistently found that female caregivers may be at greater risk for negative mental health outcomes. Female caregivers tend to report higher levels of depressive symptomatology and anxiety, and lower levels of life satisfaction, than do male caregivers. Such gender effects seem to exist among both spousal and adult child caregivers.

The quality and nature of the relationship between caregivers and care recipients can also influence caregiving outcomes. It is generally recognized that positive social ties have a beneficial influence on general well-being. In caregiving situations, greater affection or intimacy with care recipients can reduce perceived burden or strain and can lower psychological distress among caregivers. Negative social interactions while caregiving, such as family conflict and criticism of caregivers, are a risk factor for greater caregiver depression. Other problematic situations include caregivers who suffer abuse from care recipients and estranged family members who are left with ‘‘unfinished business.’’ Spousal caregivers generally spend a substantially greater number of hours per week in the caregiving role, do so for a longer period of time, and report more difficulty in sleeping, less energy, and more fatigue than do nonspousal caregivers. Spousal caregivers are also generally more willing to provide care even when care recipients need extensive care, and they are much less likely to place care recipients in nursing homes, than are adult children. In addition, spousal caregivers consistently have been shown to be in poorer health than noncaregivers. This finding is also shown for adult child caregivers; however, the increased age of spousal caregivers places this group at an even higher risk for personal physical health conditions. These findings, taken together, suggest that spousal caregivers are very committed to their roles and responsibilities, even at the expense of their own health. The vast majority of nonspousal caregivers are adult children for elderly individuals; however, African Americans are more likely to be cared for by members of their extended family than are their European American counterparts. In addition, the societal changes in marital status and number of children per family have introduced an increasing number of friends, primarily older, never married, childless women, who care for each other, and this population of caregivers is likely to increase during the coming years as the baby boom generation ages.

A second important variable in the caregiving experience is appraisal. Caregivers vary greatly in their subjective reactions to the same circumstances. Caregivers who appraise the problems they face as highly stressful are at increased risk for depression, whereas caregivers who are able to find meaning and benefit from their caregiving experience, and who have high levels of self-efficacy in caregiving, are more resilient to the negative effects of caregiving. Caregiver appraisals are often influenced by caregivers’ personalities, with a number of studies showing that neuroticism leads to negative appraisals and higher depression. Anger tends to be one of the most common negative affects among caregivers, especially the ones caring for Alzheimer’s patients and those who have poor physical health. One common cause of anger in caregivers that can be addressed therapeutically is inappropriate attributions that care recipients’ problems are intentional rather than being the effect of Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, or other brain impairments. In contrast, caregivers with personality characteristics such as high levels of optimism may be protected from some of the negative consequences of stress.

Third, research has demonstrated that coping style and social support are critical in explaining the tremendous variability in physical and mental health outcomes for caregivers. The role of resources such as social support and coping strategy is to buffer the effect of stressors on the outcome. In general, informal support networks lessen the negative consequences of caregiving such as emotional distress, health concerns, and economic strain. It is important to note that social support can be viewed not only in terms of quantity but also in terms of subjective perceptions of the quality of support. Coping is considered another important buffer and is usually separated into two categories: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Caregivers may use problem-focused coping by seeking information about their relatives’ conditions, pursuing medical advice or rehabilitative care, and/or arranging for assistance with caregiving duties. In contrast, emotion-focused coping by caregivers may include adaptive efforts such as finding meaning in adversity and distracting themselves from caregiving concerns as well as maladaptive efforts such as engaging in excessive rumination, denial, and/or substance abuse. Problem-focused coping is generally adaptive but may reach limits when little or nothing can be done to improve the objective aspects of the care recipients’ functioning. At such a point, the ability to accept limitations may be most adaptive.

5. Racial And Ethnic Diversity Issues

The sociocultural adaptation of the stress and coping model suggests that the role of ethnicity is greater than merely being a status variable reflecting the disadvantaged socioeconomic status of members of ethnic minority groups. This view asserts that one’s ethnicity and culture exert an influence on nearly all domains and stages of the stress process model, including who provides care, how caregiving demands are expected to be handled and shared among family members, how caregiving experience is interpreted and perceived, how people cope and deal with stress during caregiving, and what stress outcomes are expected. As to why caregiving experiences differ by race and/or ethnicity, some studies suggest that racial/ethnic differences in values and beliefs about aging and caregiving may be responsible for the observed differences. Although it is dangerous to generalize about racial/ethnic differences due to the risk of stereotyping, the existing literature suggests that there may be important cultural differences in caregiving; however, the individual must clearly be viewed in his or her totality and not just as a member of a racial/ethnic group.

The literature indicates that African Americans often hold different role expectations and attitudes about providing care and coping mechanisms compared with those held by European Americans. African Americans tend to hold more positive attitudes toward older adults and perceive cognitive and/or physical decline in health among elders as part of a normal process of aging. In terms of caregiving experience, African Americans report heavier workloads and more unmet needs than do European Americans; however, African American caregivers also report that they experience lower levels of stress and burden as well as higher levels of satisfaction. Moreover, African American caregivers report increased levels of religiosity in response to caregiving. They are more likely to use their religious faith and activities (e.g., prayer) as a coping strategy than are European American caregivers.

Although studies on Hispanic caregivers are limited and there is great diversity among members of this ethnic group, traditional values of Hispanic families influence their caregiving experience. One of these traditional values is familism, which emphasizes the importance of the family connection and interaction as well as the family serving as the core of the social support system. Thus, the kinship network is considered to be a very important source of social support for Hispanic elders. Family loyalty and filial piety among Asian Americans, and importance of relational networks among Native Americans, are known to be other important cultural values of ethnic groups that help to create a strong support system among them.

6. Biopsychosocial Impact Of Caregiving

The beginning of this research-paper noted that although informal caregivers ease the financial burden of long-term care for society, they do so at the risk of experiencing a variety of psychological, physical, and social consequences of caregiving. Research at this point has clearly demonstrated diverse effects of caregiving, but questions remain as to what degree and in which areas such effects occur.

One of the most consistent and well-researched relationships regarding the effects of caring for chronically or terminally ill individuals is the increased risk of depression. The availability of validated quantitative tools for evaluating depression has led to comparability across studies and confidence in the strength of the results. The actual rates of depression vary; however, most studies find that caregivers who are involved in dementia care, or in other extensive caregiving, are two to three times more likely to be at risk for clinically significant depression than are their noncaregiver counterparts. In addition, many caregivers experience subsyndromal or subclinical levels of depression. Caregivers are also much more likely to use psychotropic medications for mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, than are noncaregivers.

To better understand the relationship between caregiving and increased risk of mental health problems, it is necessary for researchers to identify risk factors. Documented risk factors for increased distress during caregiving include being female, experiencing other stressful life events (e.g., bereavement), lacking social support, experiencing family tension, being younger, being in poorer physical health, ruminative thinking, and having lower education. Research has also identified a number of factors that appear to be protective against negative mental health outcomes, including high levels of self-esteem and mastery, high ratings of optimism, high ratings of life satisfaction, and low ratings of neuroticism. The findings regarding patient diagnosis have been inconsistent, with some reporting that caregivers for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease experience higher rates of depression and others reporting that the rates are comparable between diagnoses such as cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

An important emphasis of research in this area seeks to determine how long these changes in mental health status last, with a fairly large number of studies finding that elevated levels of depression are seen in some individuals for as long as 2 to 5 years following the loss of loved ones, although there is also evidence that some caregivers experience improvements in mental health when their caregiving ends. Additional longitudinal data are needed in this area to better understand what places an individual at risk for this type of chronic bereavement reaction.

Research on the physical health effects of caregiving has varied greatly in its sophistication in assessing health outcomes. A common assessment of physical health status in caregiving studies is a single-item self-rated health question, and more of these caregivers rate their health as poorer than do noncaregiving controls or population norms. Many studies in this area have used this single item as a proxy for physical health in the participants, and although research has demonstrated that this method can be reliable, more sophisticated methods are needed for success in this research. There have been few longitudinal studies of the impact of caregiving on physical health. One large study comparing caregivers with noncaregivers of similar ages indicated that caregivers showed increased physical health symptoms over a 2-year period, whereas noncaregivers showed no increase over time. Other studies have used more sophisticated measures

of physical health. These studies indicate that caregiving can lead to increased health risk behaviors (e.g., drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes), lower levels of physical exercise, changes in sleep patterns, decreased immune system functioning, altered response to the influenza vaccination, slower wound healing, increased blood pressure, and altered lipid profiles. There has also been interest in whether or not these physical health changes lead to increased mortality in caregivers, and this question was examined in the Caregiver Health Effects Study. This prospective, population-based cohort study followed caregivers for an average of 4½ years and reported that caregivers who experience strain while in the caregiving role showed a 63% increase in mortality as compared with caregivers who did not experience strain and noncaregiving controls. Additional work is needed in this area to identify the mechanisms underlying these physical health changes and increases in mortality; however, this research has been very valuable in demonstrating that caregiving can represent a major and clinically significant strain.

Caregivers commonly report that their responsibilities infringe on their personal and social lives. Caregivers often are unable to take part in leisure activities, vacations, and/or valued activities such as church attendance. Spousal caregivers become devoted to their roles and the responsibilities they entail, often at the expense of their own needs, including social interaction. They report spending less time engaging in social activities (e.g., having lunch with friends, spending time with grandchildren) and in personal hobbies (e.g., gardening, sewing). A small group of caregivers, particularly adult daughters, are sometimes described as the ‘‘sandwich generation’’; in some cases, they are responsible for caring for their own children as well as for their parents. Some researchers believe that this may become an increasing phenomenon given the current trend toward women holding off on having children until later in life. These caregivers very commonly report significant changes in their employment status (e.g., decreased hours, extended leave, leaving the workforce altogether) as a result of time constraints due to the needs of their aging parents. The specific effects vary based on relationships to care recipients; however, the overall pattern appears to be consistent in that caregivers sacrifice their social and personal roles to accommodate the needs of their loved ones.

The cyclic relationship among mental health, physical health, and social engagement is a concern for health care workers and clinicians. Increases in depression and physical health problems can lead to decreased social interaction; however, the reverse is also true in that role constraints that inhibit social activities can lead to negative mental health outcomes, specifically increased depression. An additional concern is in the case of bereavement following a period of caregiving. The literature has demonstrated that low social support and mental and physical health problems during caregiving can lead to complications during bereavement. Therefore, if individuals have experienced these changes as a result of the caregiving experience, they are at risk. It is important to identify caregivers who are at risk for these negative psychological, physical, and social outcomes so that they can be targeted for assistance before the complications progress.

Finally, it should be noted that caregiving can lead not only to negative impacts but also to benefits. Recent studies show that caregivers often report benefits from caregiving such as a sense of satisfaction, a feeling that they are repaying care they received when they were young, and feelings of mastery and accomplishment. These positive feelings can occur simultaneously with negative effects.

7. Interventions For Caregivers

Each individual in a caregiving situation can experience his or her responsibilities and role as a caregiver differently due to that person’s unique characteristics and circumstances. Moreover, caring for loved ones can be a meaningful and positive experience. However, caregiving can also lead to negative psychosocial and physical outcomes such as depression, lowered level of physical health, and lowered sense of well-being. Thus, many caregivers are in need of psychosocial and instrumental support. With an increased knowledge of how various stressors and other caregiving characteristics interact with each other and lead to different outcomes, various intervention methods have been developed and provided to caregivers in different caregiving settings. These interventions have also been evaluated for their clinical significance and effectiveness in both statistical and practical ways. A number of studies that summarize, evaluate, and examine the strengths and weaknesses of currently available caregiving intervention research literature have been published. These review studies can provide further detailed knowledge and information on the progress of caregiving intervention research. However, this research-paper focuses on providing an overview of the caregiving intervention research, including primary entities being targeted by the interventions, types of interventions, and effectiveness of these interventions.

In general, interventions need to be tailored to specific needs of caregivers who have diverse and unique characteristics and caregiving experiences. For example, a caregiver who is dealing with severe behavioral problems due to dementia might want to learn about the nature and course of disease progression and how to handle behavioral problems effectively. On the other hand, a caregiver who has recently placed a loved one in a nursing home might seek an intervention that can help him or her to cope with feelings of guilt. Therefore, caregiving interventions are designed to reduce different types of stress outcomes so as to meet unique individual needs of caregivers and their care recipients.

There are a few major domains of stress outcomes for which various intervention methods aim to improve. These outcomes include how caregivers respond to stress in terms of mental and physical symptoms, improved general sense of well-being and quality of life, and delayed institutionalization of care recipients. Symptoms that caregivers often exhibit in reaction to caregiving stress include elevated levels of depression, anxiety, anger, and hostility as well as lowered health status (often measured by self-reported health and blood pressure). Also, quality of life of caregivers is often measured broadly by life satisfaction, sense of burden, mood, and social support. Finally, other outcomes targeted for intervention include care recipient outcomes such as functional status and delay of institutionalization of care recipients and use of formal and informal support as well as services available to caregivers.

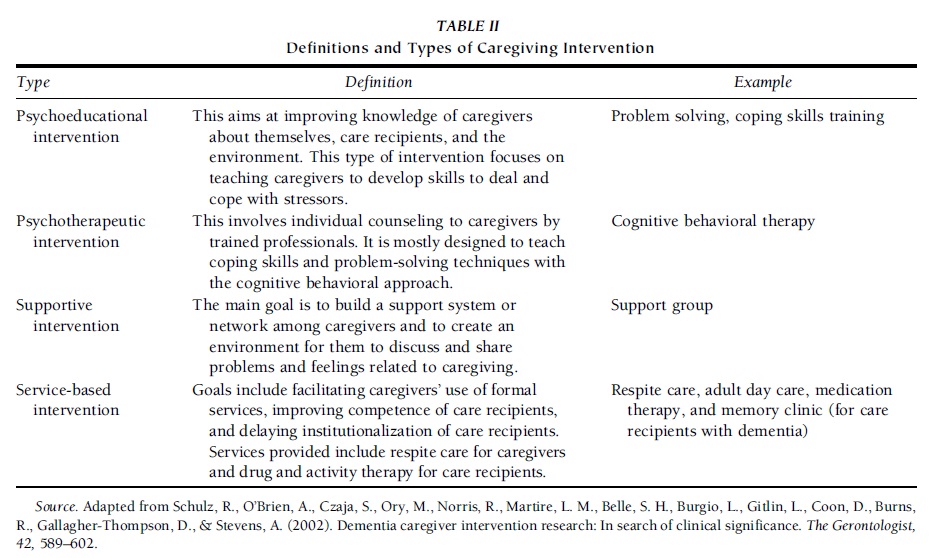

Caregiver interventions are focused on either improving quality of life and coping skills of caregivers or reducing the objective stressors such as amount of care provided by caregivers. These interventions include psychoeducational, psychotherapeutic, supportive, and service-based interventions. The psychoeducational intervention is often offered with other types of interventions and aims to improve caregivers’ knowledge about themselves, care recipients, and the environment. This type of intervention focuses on teaching caregivers to develop skills in dealing and coping with stressors through providing comprehensive information on characteristics of disease process of care recipients, resources and services that caregivers can use, and other specific coping skills. Psychotherapy is another form of intervention that is often used in conjunction with psychoeducation involving individual counseling to caregivers by trained professionals. This type of intervention is usually designed to teach coping skills and problemsolving techniques with the cognitive behavioral approach.

Supportive intervention is another type, and its main goal is to build support systems or networks among caregivers and to create an environment for them to discuss and share problems and feelings related to caregiving. Thus, supportive intervention is focused on allowing participants (i.e., caregivers) to exchange ideas and strategies for coping with stressors and difficulties. Service-based intervention programs usually provide respite and/or adult day care services. Respite and adult day care programs are designed for caregivers to take some time off from caregiving responsibilities by providing assistance with ADLs and/or certain activities for care recipients. Other types of intervention methods include providing memory training, activities, and medications to care recipients as well as relaxation training to caregivers.

Most of these interventions are multifaceted in their design and method, and they usually are offered in conjunction with other methods. This makes it difficult to attribute any specific component of intervention to the success of intervention outcomes. Moreover, the caregiver intervention literature shows that most of these interventions show some level of effectiveness, yet it appears that there is no single method that is clinically significant and effective across caregivers. However, in general, a combined form of individual educational and psychotherapeutic interventions tends to result in better outcomes than do group interventions. Moreover, psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions are found to be effective in reducing

levels of depressive symptomatology as well as anxiety and anger. In addition to psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions, behavior management training, stress management, and use of certain medications are known to be effective in increasing sense of well-being and quality of life of caregivers as well as in delaying nursing home placement of care recipients with Alzheimer’s disease.

The majority of caregivers are likely to benefit from gaining knowledge about the diseases, caregiving tasks, and available resources. Some caregivers can obtain additional help by receiving training in coping and problem-solving skills as well as in behavioral management of care recipients. In addition, some studies have found that providing a mixed form of interventions that are given to both caregivers (e.g., psychoeducational intervention) and care recipients (e.g., medication, therapeutic activities) can also be effective. Furthermore, a fairly new approach to caregiving interventions involves using technologies such as enhanced telemedicine, computers, and the Internet. Table II provides an overview of some of the types of interventions described previously, including definitions and examples.

TABLE II Definitions and Types of Caregiving Intervention

TABLE II Definitions and Types of Caregiving Intervention

8. Concluding Comments

Family caregiving is a topic that demands greater attention from researchers, clinicians, and those concerned with public policy. The aging of the baby boom generation may stimulate greater attention to the possibility of changes in public policy that provide more support for caregiving families. For example, in other countries, family caregivers may receive pay in recognition of their efforts, adjustments to their retirement benefits, vouchers that can be used to purchase community services, and other forms of support that recognize the value of family caregivers in preventing expensive and unnecessary institutional care.

References:

- Aneshensel, C. S., Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Zarit, S. H., & Whitlatch, C. J. (1995). Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Aranda, M. P., & Knight, B. G. (1997). The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 37, 342–354.

- Coon, D., Gallagher-Thompson, D., & Thompson, L. W. (Eds.). (2002). Innovative interventions to reduce dementia caregivers’ distress: A clinical guide. New York: Springer.

- Haley, W. E., Allen, R., Reynolds, S., Chen, H., Burton, A., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2002). Family issues in endof-life decision making and end-of-life care. American Behavioral Scientist, 46, 284–297.

- Haley, W. E., Roth, D. L., Coleton, M. I., Ford, G. R., West, C. A. C., Collins, R. P., & Isobe, T. L. (1996). Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in Black and White family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 121–129.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Marucha, P. T., Malarkey, W. B., Mercado, A. M., & Glaser, R. (1995). Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. The Lancet, 346, 1194–1196.

- Mace, N. L., Rabins, P. V., & McHugh, P. R. (1999). The 36hour day: A family guide to caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease, related dementing illnesses, and memory loss in later life (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mittelman, M. S., Ferris, S. H., Shulman, E., Steinberg, G., & Levin, B. (1996). A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 276, 1725–1731.

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594.

- Roth, D. L., Haley, W. E., Owen, J. E., Clay, O. J., & Goode, K. T. (2001). Latent growth models of the longitudinal effects of dementia caregiving: A comparison of African-American and White family caregivers. Psychology and Aging, 16, 427–436.

- Schulz, R., & Beach, S. R. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 2215–2219.

- Schulz, R., O’Brien, A., Czaja, S., Ory, M., Norris, R., Martire, L. M., Belle, S. H., Burgio, L., Gitlin, L., Coon, D., Burns, R., Gallagher-Thompson, D., & Stevens, A. (2002). Dementia caregiver intervention research: In search of clinical significance. The Gerontologist, 42, 589–602.

- Sorensen, S., Pinquart, M., & Duberstein, P. (2002). How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 42, 356–372.

- Stephens, M. A. P., & Franks, M. M. (1995). Spillover between daughters’ roles as caregiver and wife: Interference or enhancement? Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences B, 50, P9–P17.

- Teri, L., Logsdon, R. G., Uomoto, J., & McCurry, S. M. (1997). Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: A controlled clinical trial. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences B, 52, P159–P166.

- Weitzner, M., Haley, W. E., & Chen, H. (2000). The family caregiver of the older cancer patient. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, 14, 269–281.

- Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E., & Bach-Peterson, J. (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20, 649–655.

- Zarit, S. H., Stephens, M. A. P., Townsend, A., & Greene, R. (1998). Stress reduction for family caregivers: Effects of adult day care use. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences B, 53, S267–S277.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.